Chapter 2. What Makes Me a Rebel at Work?

Do you ever say…

Are you a person who…

- Is curious, paying attention to emerging trends and how they might affect your work?

- Names the elephant in the room and has ideas about how to get it out of the room?

- Steps in to take on gnarly tasks that require creative solutions?

- Has been told more than once by a boss to “give it a rest because that’s not how we do things around here”?

If you answered “yes” to one or more of these questions, you may very well be a rebel at work. Rebels ask hard questions, don’t take things at face value, and don’t accept that things have to be the way they’ve always been. We are also often the ones who can see the future coming and pick up on subtle indicators of change before others do. Above all, we’re people who want to create positive changes, not just whine about what’s not working. We’re an oddly optimistic bunch, believing in what’s possible while many of our coworkers give up.

Good Rebel from Birth?

Many rebels were born that way. Think back to incidents from your childhood and early adult years. Were you a handful even then?

We’ve heard hundreds of origin stories from rebels at work, and most—though not all—knew they were different early on in life, strongly suggesting that there is something about being a rebel that is born not made.

Venture capitalist and former Bell Labs scientist Deb Mills Scofield remembers that when she was three, her father told her to stand in the corner and think about what she had done. “Apparently I told him he could tell me where to stand but he couldn’t tell me what to think,” she recounts.

Encouraged by his parents to think for himself, designer Phil Schlemme stood up to his teachers in elementary school. They said he talked too much, though they admitted that what he had to say was interesting and benefitted the class. When he was seven, teachers asked the students what they most wished for. Most kids drew pictures of dolls and footballs. Phil said he wanted peace between Iraq and Iran and drew a picture of the countries’ two flags. Around this time, he also decided he shouldn’t have to wear the school uniform. Though his parents supported his decision, they taught him about conciliation and pragmatism. “My parents and I agreed that though it was all right to stand up to authority and think for myself, it might be wise to wear the school uniform occasionally so as not to cause a stir,” he explains.

Episcopal priest and executive coach Maria DeCarvalho’s independent spirit came to the forefront when she represented her high school as a delegate to the Girls’ State Convention, sponsored by the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Auxiliary. “I explained to my hosts that I would not sign the required pledge to salute the American flag. I was happy to salute the flag but not happy to submit to a requirement that I do so. It was ironic,” she said. “At the end of the week, the wonderful—and I absolutely mean that—women of the VFW Auxiliary awarded me the Citizenship scholarship, which came to something like $100.”

It’s amusing to us that our rebel stories are almost diametrically opposed. There’s no one rebel type. Rebels come in a broad range; just look at us!

Rebels Along the Way

Being a rebel when you’re young does not necessarily mean you will continue being a rebel as an adult. Nor does it mean that you won’t emerge as a rebel later in life. For some of us, the appetite to question persists or reawakens at some point in our careers.

Matt Perez found out he was a rebel while serving as a platoon leader in the US Army. His senior officers didn’t want a female member of his company to be deployed to the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Shield. Matt lobbied for her to serve with her company.

“From their perspective, sending a lone woman to a war zone was disruptive and counterproductive. I argued that, according to Army doctrine, we train as we fight. The woman in question was a noncommissioned officer and had trained to do this job, with this unit, in combat. To leave her behind because of her gender was a copout in my opinion. I pushed for her to go, against the judgment of my superiors, and despite my fear that any harm that came to her would be on my conscience.”

Matt’s story also illustrates how emotionally draining it can be to stand up for the right thing.

Note

You aren’t a rebel at work the first time you voice an opinion different from the prevailing orthodoxy of your organization. You become a rebel at work when you decide to continue speaking up despite the costs.

Three Common Rebel Tendencies

How we think determines how we act. In researching rebels, we have found that they think differently from most of their coworkers. Many good rebels:

- Are future thinkers

- Tend to be more energized by creating possibilities than achieving certainty.

- Tend to work ahead

- See emerging trends early. Think several steps ahead of most coworkers.

- Are different

- Come from a different background or culture, so bring different ways of thinking to the workplace.

Being a Future Thinker

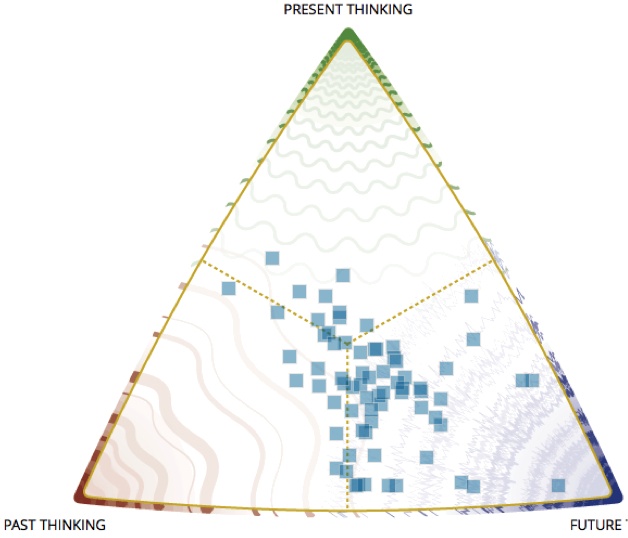

To learn more about the thinking styles of rebels at work, we asked rebels to map their thinking styles using the MindTime® behavioral mapping system.

We found that the majority of rebels are future thinkers. Rebels can’t stop thinking about possibilities and imagining better alternatives. We’re driven to change, look for opportunities, and like working with ideas.

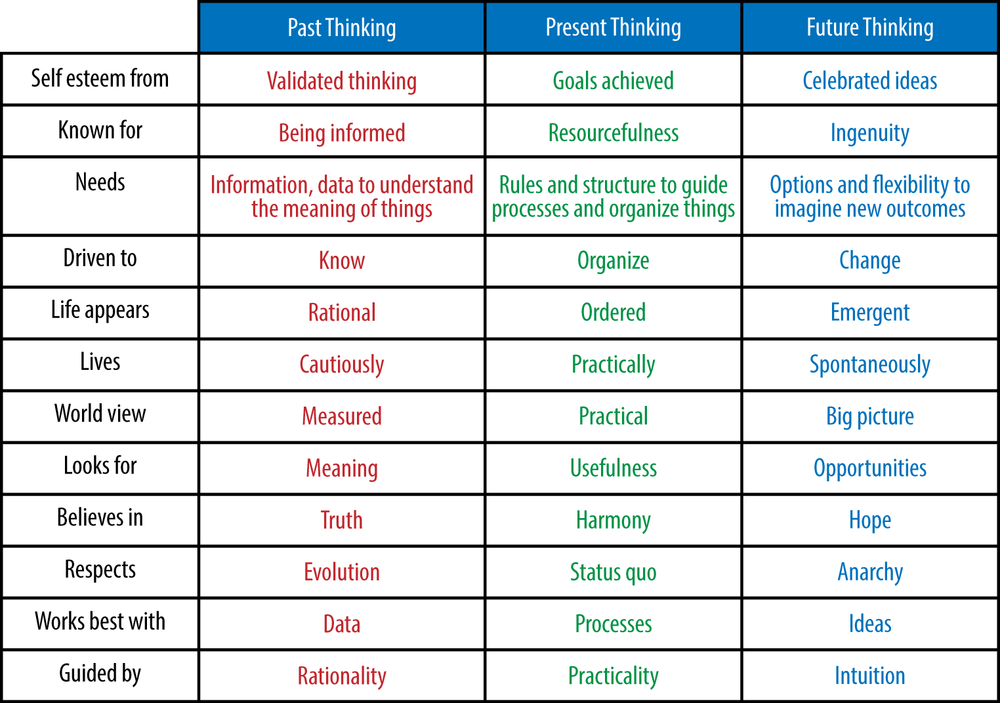

MindTime assesses how people think, uncovers why they behave the way they do, and helps predict what they will do. MindTime uses a phenomenological framework—past, present, and future thinking—as a way to understand people. Three time-based patterns help explain your cognitive style:

Figure 2-1 lists characteristics of the three thinking styles. Looking at MindTime’s visualization of the results, we see significant clustering in the results (see Figure 2-2), showing that we rebels do, for the most part, think very much alike.

The rebels in this experiment were predominantly future thinkers, but they were not 100 percent future thinkers. Most rebels fell in the intersection of future, past, and present thinking. This means that while their predominant thinking style is future oriented, they also have past or present thinking styles as well, enabling them to bring a practical approach to solving present-day problems and draw on data and past experience to validate new ideas.

If you were an extreme future thinker, with little past or present thinking, you would likely get lost in possibilities and not be able to complete projects. Paradoxically, if the majority of the people in an organization are future thinkers, the organization might behave very creatively and energetically but actually move too slowly to succeed, spinning in ideas but lacking the practical skills to realize them. To get good work done, organizations need people with all three thinking styles.

We find this mapping system useful not only in understanding your own style, but also in understanding how people in your organization think so that you can present your rebel strategies in ways that appeal to decision makers’ ways of thinking. (We address how to do this in Chapter 5.) If managers are predominantly past thinkers, you should present solid data and research to support your idea. For present thinkers, show how your idea can be practically accomplished and meet the organization’s goals. And if you’re talking to a group of future thinkers, it’s all about possibilities and opportunities.

Even if you don’t use MindTime, you can begin to understand how people think by listening to the language they use and the questions they ask. Do they ask for best practices, research data, and examples of what other organizations are doing? Do they say they’re not comfortable making a decision without more analysis? They are probably past thinkers. Do they probe for details on how the project would be managed? Ask what type of resources it would take? What current fiscal year goals it would help accomplish? They are present thinkers.

This future-thinking trait may be why so many of us think way ahead of most of our colleagues, which can be both an asset and a frustration. It also relates to the next rebel characteristic: “working ahead.”

Working Ahead

In her article “Counseling Gifted Adults,” counselor Paula Prober describes the early educational adventures of Susan, who was labeled as gifted. Susan recalled being thrilled about starting school but was very quickly disappointed. In second grade, she completed an entire reading workbook in one night. With pride, she showed it to her teacher the next day and was reprimanded for “working ahead.”

While we may not have been labeled as gifted children, many of us were reprimanded at some point for “working ahead” and pushing new ideas too fast. We can’t help it, or at least we can’t control it until we become painfully aware of its impact on the workplace and on our careers.

Many of us see emerging trends and work ahead to figure out the essence of the trend and how our organizations can use it to their advantage. The challenge of working ahead is twofold: helping people understand and see the value of something so new, and not becoming bored by an important trend by the time the trend starts to be adopted.

But as rebels, we like living in the world of emerging possibilities. Executing the same types of processes and programs over and over again bores many of us.

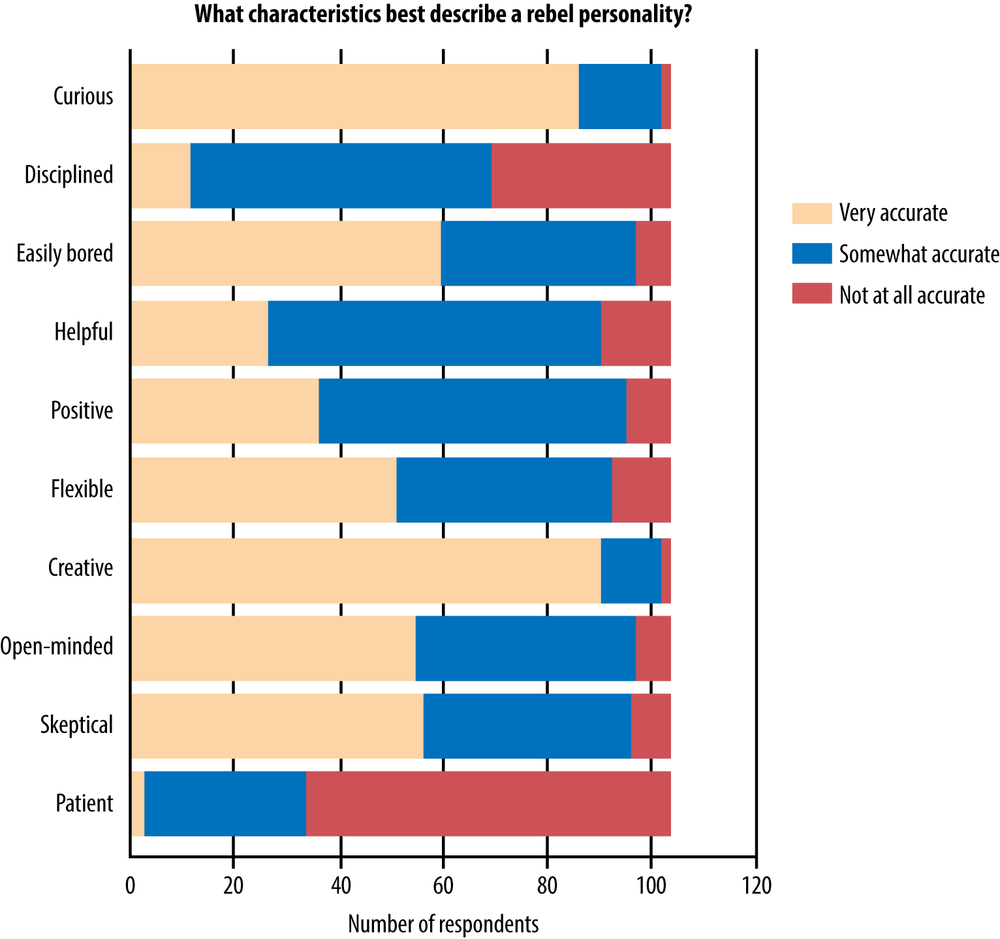

In an online research study we conducted of 150 self-identified rebels at work, 94 percent said that “easily bored” is a very accurate (57 percent) or somewhat accurate (37 percent) description of rebels. Similarly, less than a third think rebels are patient. See Figure 2-3.

Working ahead is what rebels do, but it must be balanced. Perseverance and tenacity are as necessary for creating change as seeing the opportunity.

Being Different

Because rebels think differently from most people at work, we are like any minority group inside a company. Companies often make space for people who are different as part of their diversity efforts, but they don’t make space for their perspectives. In other words, if you were raised in a different culture, say Latin America, and you work in a Scandinavian company, you naturally bring different experiences and cultural perspectives based on your background. If your first career was in the military and you are now teaching in a charter school, you will have a different approach from teachers who never served in the military.

Differences are accentuated when you are also a member of a minority group. We have discovered that being a minority or a woman significantly increases the chances that you could be a rebel at work. In significant ways, women and minorities are often perceived as rebels at work, not fitting in and not understanding the corporate culture, even when they have no rebel intent. Their diverse backgrounds, unique experiences, and different cultural frames of reference contribute to them having different opinions and uncomfortable reactions to the status quo. It is sometimes overwhelming and confusing.

We suspect that many of you with diverse ethnic backgrounds view things differently from the majority culture at your place of work. Hopefully your organizations understand that people with different backgrounds bring different perspectives and ideas, and that this diversity of thinking is extremely valuable.

But we also know that many organizations value their corporate cultures above all else. In these organizations, you often hear a manager say things like “It’s a shame about so-and-so. He has some interesting ideas but he doesn’t quite know how to fit in.” Or, “You have great potential but you need to learn to be more corporate.”

Many sincere attempts to diversify organizations fail because leadership wants the appearance of diversity but not its impact. Any significant effort to bring diversity to your organization is tantamount to the injection of an important new way of thinking.

Note

Helping rebels be more effective at work is a diversity initiative. Increasing the impact of diversity on an organization is also a rebel initiative.

It’s important for all minorities to understand that their organizations may not always be open and receptive to their ideas. To advance those ideas, they should feel free to borrow many of the tactics we recommend for rebels at work, even if they don’t consider themselves rebels.

Accidental Rebels

“I didn’t ask for this,” you might be saying. Just as some people are naturally rebels because of their thinking styles and reactions to what’s happening around them, others simply find themselves thrust into the role of being a rebel.

You might remember that one characteristic of good rebels we listed in Chapter 1 was reluctance. If you feel that way, it could be that you are an accidental rebel. It could also be that you are a rebel who has never wanted to see yourself that way.

Accidental rebels are drafted by their boss or by a cause relevant to their family or community. They may or may not have stories about being a rebel in elementary or high school, be future thinkers, or work ahead. They wind up taking on a role they never really wanted.

Patient-Advocate Rebels

What if a health crisis hits and you’re afraid your loved one is not getting the care he needs? Without any intention of becoming a rebel, you step up and become a patient advocate, a type of accidental rebel.

Pat Mastors was a TV news anchor and medical reporter for more than 20 years before her father was hospitalized. A hospital-acquired infection, Clostridium difficile, ruptured his intestines; he died six months later. Pat was called upon to be a patient-advocate rebel again three years later when her brother battled a rare cancer diagnosis, and when her mother had cancer surgery the following year.

But it wasn’t until May 2013, when her 26-year-old daughter Jess developed symptoms of numbness and paralysis, that Pat fully understood the helplessness of having to rely on others to save someone you love and the need to go into full rebel mode in order to save your child’s life.

Jess had hiked the entire Appalachian Trail the year before. Now she could barely move, stricken by Guillain-Barré Syndrome, an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks myelin, the coating that protects the nerves. GBS strikes randomly and symptoms develop fast. Within days, her daughter could have been completely paralyzed.

Pat and her husband went into action, calling on every resource they had. Though they had confidence in Jess’s medical team, Pat had learned too much as a patient advocate. Like all rebels, she knew that she must speak up, ask the tough questions, and be tenacious about getting answers and commitments from people who in many cases would like you to just go away and stop bothering them.

Despite the odds, Pat’s daughter recovered. Did Pat’s rebel actions make a difference? She’ll never know. But she does know that people need to understand how to stand up to institutions and bureaucracy. To that end, Pat has recently published Design to Survive, a book that empowers people to be patient advocates.

Corporate Social Responsibility Rebels

Sometimes the field you are in asks you to be a rebel at work. One example is corporate social responsibility (CSR), which requires organizations to create change and go against the way things have always been done.

Some people in CSR chose to work in the field and anticipated the challenges of getting companies to act with greater and greater commitment to societal needs. However, if you are drafted into a CSR role, you become, in effect, an accidental corporate rebel. You are asked to do something that may be foreign or unpopular in many areas of your company. Your job description may label you as the “champion” for CSR in your organization—a telltale sign, we believe, of an accidental rebel position. To succeed, you need to be both a good and an effective rebel.

These are just a couple of examples of accidental rebels. There are many more who find themselves taking up the rebel mantle by necessity.

Note

This ends the context about good rebels. If you’re a possibility-oriented, work-ahead kind of rebel, we bet you’re getting antsy, wanting to get to the guts of how to push the boundaries at work. This ends the overview about rebels.

All the following chapters dig into the “how to.”

Questions to Ponder

- In what situation did you first realize you were a rebel? What did you learn about yourself?

- What rebel characteristics best describe you? Future thinker? Diverse outside thinker? Work-aheader? Something else?

- When you think about good rebels in your life, what makes them unique? What could you learn from them?

- What rebel in history do you most admire? What characteristics of that person would you most like to emulate?