5

Listening Is Understanding

No man ever listened himself out of a job.

CALVIN COOLIDGE

NOW THAT YOU’VE PREPARED yourself to present your designs and anticipated what the responses will be, you have the opportunity to actually meet face to face with the people who have influence over the project. This is where our skill at communicating really begins, but not because of anything that we say. The first thing we need to do is listen.

Listening is an important skill for every relationship, and it’s no different when discussing design decisions. Listening isn’t just waiting for the other person to stop speaking so that we can begin our response. The entire purpose of careful listening is to ensure that we understand our stakeholders before responding.

A proper and articulate response requires that we use implicit skills such as listening without interrupting, hearing what they’re not saying, uncovering the actual problem they’re trying to solve, and then pausing before moving on. We also must use more explicit techniques like taking notes, asking questions, and repeating or rephrasing what was said. Using these tactics, we can outwardly demonstrate that we understand what they’re saying. Because most stakeholders don’t speak our designer jargon, we must listen closely for the clues that will help us to attach their words to our designs, and when we respond, we need to use language that will be effective for everyone. We want to understand exactly what they’re saying so that we can form the best response.

Implicit Activities

Implicit listening is applying skill in understanding what people are saying without outwardly doing anything specific to demonstrate that we hear them. An implicit listener is one who can quickly organize what’s being said and derive meaning without any other external clues or further information. For the purpose of listening to design feedback, I’d like to highlight four ways we can implicitly mine stakeholder feedback to get at the core information we need to respond.

LET THEM TALK

The first thing you should do is to let your stakeholders talk as much as they want without interrupting. That’s right, allow them to say as much as they need to and don’t cut them off. People like to hear themselves talk, and they need enough space and time to express themselves without feeling rushed.

It can be difficult not to interrupt someone providing feedback on your work, especially if they’re saying things you know to be incorrect or uninformed. Besides, we also like to hear ourselves talk! It’s difficult to hear someone talk about your design work without feeling the urge to jump in and contribute your own ideas. After all, it’s your design they’re talking about. But don’t stop them. It is to your advantage to let everyone finish first.

There are a variety of reasons why people need to talk so much. Some people just want to sound smart in public. It could be that there are other people in the room who they’re trying to impress. As I mentioned in Chapter 3, you never know what sort of politics are at play. Other people are audible learners, and the process of talking about something helps them understand it more clearly. In fact, because design can be so difficult to talk about (especially for nondesigners), the process of talking through one’s thoughts may allow stakeholders to arrive at their opinions over time. They might even eventually explain your design to themselves in the process without you having to say a word. Whatever the reason, allow your stakeholders to say their piece before moving on.

There are three main benefits to letting them talk as much as they want:

They will make themselves more clear

As people talk, they naturally repeat themselves and rephrase what they mean in an effort to communicate clearly. Because your job is to understand exactly how they see your designs, it’s critical that you give them the space they need to describe them. Not everyone knows the vocabulary to use when discussing design, and it can take them a few tries to fully express themselves.

It gives them confidence that they were understood

The more people are able to say what they need to get a point across, the more confidence they’ll have that they did just that. You want your stakeholders to know that they communicated effectively so that they can’t blame a misunderstanding on their inability to communicate (or your inability to listen). Letting them talk gives them room to have that confidence.

It demonstrates that you value what they’re saying

No matter what you say in response, allowing stakeholders to talk as much as they want communicates to them that you appreciate what they’re saying and you’re listening to every word. When you make them feel that way, it builds trust and they’ll be more likely to agree with you later if they know they’ve been heard.

While they talk, present yourself as valuing their input by maintaining eye contact and nodding your head in agreement. Be sure to listen for specific words they use; for example, pay attention to any jargon they use and terms they prefer when describing your designs. Most people won’t use language such as UI control, input element, drop list, popover, carousel, or tooltip. Part of your job with listening is to figure out what words they’re comfortable using to describe your designs so that you can use those terms, too, when you respond. It will be difficult to earn their approval if you’re using a different vocabulary; therefore, adopt the words that they use and also (eventually) find ways to teach them terms that will be more effective in the future. We’ll look at this more in the section “Repeat and Rephrase.”

Overall, allowing stakeholders to talk freely creates an atmosphere in which your stakeholders know they can express themselves without being interrupted, which makes them more likely to tell you what they think every time. They know that this is a safe place for them to express themselves and be heard.

HEAR WHAT ISN’T BEING SAID

Not everything that our stakeholders say will be immediately clear. Sometimes, we need to look deeper than their actual words to derive their intended meaning. So, another important part of listening to your clients and stakeholders is to hear what isn’t being said. You have to try to understand both what they’ve expressed out loud as well as what never came out of their mouths. What’s the subtext? What is the elephant in the room that no one really wants to mention? Often, what people say and what they mean can be two completely different things.

This might be more important in design than any other field simply because design is more subjective and people aren’t always sure how to express themselves. Further, your stakeholders realize this is something that you made. You created it. It’s your baby. They may be sensitive to that fact and try to tell you about a problem they see in indirect ways. If this is the case, people commonly respond with questions rather than direct disagreement. “Oh, that’s interesting. Why did you use the primary call to action here instead of the secondary one?” The subtext might actually be that this person thinks the secondary call to action is a better choice but they just don’t want to come out and say it that way. Any time someone uses the word “interesting” in a response to your designs, that’s a big clue that they disagree with your approach.

As I’ve mentioned before, there are other factors going on in every meeting we’re simply unaware of. If one person is being disruptive about something benign, perhaps he’s trying to make a point to someone else in the room. Or, when your manager didn’t care about the dashboard graphs last week but is now suddenly insisting that they be changed, maybe she’s reacting to the meeting she just returned from with her own boss. We can expect that there is often something else going on.

Polite Paula

In one of my previous roles, I pitched an idea for a web interface that was a little unusual. My manager responded with enthusiasm because she knew I was excited about the idea and wanted me to succeed. She was the kind of person who was always supportive. She agreed to let me spend Fridays working on this side project so that it didn’t distract me from my regular work during the week. For several months, I worked on this new idea, and when it was ready I brought it to her for feedback. She was so nice but rather than tell me outright that it was a disaster, she instead asked me questions about it in a way that showed me the flaws in my design. Because it was my pet project, I was naturally a little defensive. I answered her questions as best as I could, but in the end it was unclear to me what she wanted me to do. Looking back, I realize now that she was just trying to tell me indirectly that she didn’t think it was worth pursuing. I would have preferred if she had been up-front with me about it, but I couldn’t control how she chose to respond to my work. We have no choice but to hear what they’re not saying if we have any hope of knowing the best way to respond.

Discouraging Dan

At another company, I worked on a marketing site for an online service. The site was completely broken: bad links, missing images, and outdated copy. It looked like an abandoned house. As it turns out, an unusual number of support questions were related to simple problems with this site. I knew the product owner didn’t have the resources to redesign it. To me, it was low-hanging fruit: a simple five-page brochure site that could quickly be templated and updated. Because it really bothered me that the site was broken, I decided to redesign it while I was in between projects. My thinking was that an improved and functional website would be better than a perfect and infinitely delayed one. The first design I showed to the product owner was met without enthusiasm. “Oh...um, wow, Tom. That’s really nice, thank you. It looks much better, but you really don’t need to be spending time on this,” was his reaction. I assumed he was just being nice. He wasn’t my boss and didn’t have the authority to ask me for help, but the site clearly needed some TLC. What could it hurt? I finished the designs, created the pages, and put it on a staging server. Again, the product owner wasn’t excited. He appreciated my effort and gave me the green light to put it in production, but it seemed like he couldn’t care less that I had done him this favor.

A few weeks after putting it into production, our group received an email announcing that this service was being shut down immediately, the marketing site would be taken offline, and existing customers would be given a transition period to find a new service. I can only assume that this product owner could not tell me that the service was being discontinued at that time. He tried to discourage me from working on the site, but I was not astute enough to read between the lines. Although I don’t regret the time I invested in it (because I am proud of the way it turned out), I could have redirected my effort to something else that would have had a bigger impact if I had been skilled enough to hear what wasn’t being said. I should have dived deeper to understand his lack of enthusiasm before blindly moving forward on my own. These kinds of subtle cues are easy to miss and require a keen understanding of our stakeholders.

UNCOVER THE REAL PROBLEM

While you’re listening to your stakeholder’s feedback, work to uncover the real problem they’re trying to solve. Often, our stakeholders see a need that isn’t being met with our designs and they may express it with a suggestion that isn’t the right solution. So, don’t focus on what they think needs to be changed or the specific words they use; instead, focus on the underlying problem they’re trying to solve by suggesting that change.

People naturally think in terms of solutions rather than first identifying the problem. Because design is visual, it’s much easier to say “Move this button over there” than it is to recognize that the problem is the proximity between the button and the date picker. Other times, people use vague language simply because they don’t know how to express their reaction to a design. When someone says, “There’s way too many colors here! It’s like a rainbow,” what they’re actually expressing is, “The number of colors are distracting and I don’t know where to look or what’s important.” We can help our clients understand the real problem by asking questions and repeating it back to them (in the following sections), but first we need to be on the lookout for this situation.

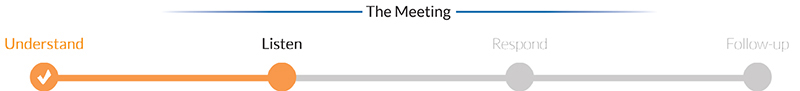

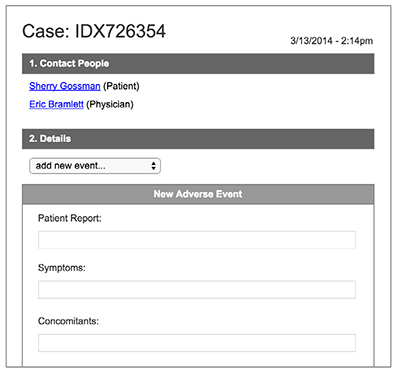

Reordered Inputs

A client once asked me to change the order of some text input fields on a form. It was a simple request. She just wanted to move some things around, but it struck me as odd because we had already agreed on the most efficient way for a user to enter the data. Although simple, her request was contradictory to what we had previously agreed upon. When I asked her why, her response was nothing more than an expressed preference: she simply preferred that the data be entered in that way. I asked her for an example of another application that did this and she sent me the spreadsheet that she gets as an export from the system, which she uses to generate reports for her meetings. Now, she didn’t actually think that our app needed to look like a spreadsheet; that’s not what she was trying to accomplish. However, in her explanation she mentioned that the order of the columns in the spreadsheet needed to match the data entered in the system. She thought that the way the user entered the data in the form would be reflected in the exported file that she would get from a dump of the database. She had no idea that we could customize the order of the data in the report for her, independent of the user’s input. Had I made the simple change she originally requested without question, it would have resulted in a less optimal experience for the user. By digging deeper and understanding the real problem she was trying to address, I was able to respond and address her concerns without changing the design at all.

My client asked me to change the order of some input fields because she didn’t realize that the exported file could be independently ordered from the user’s input.

Duplicate Data

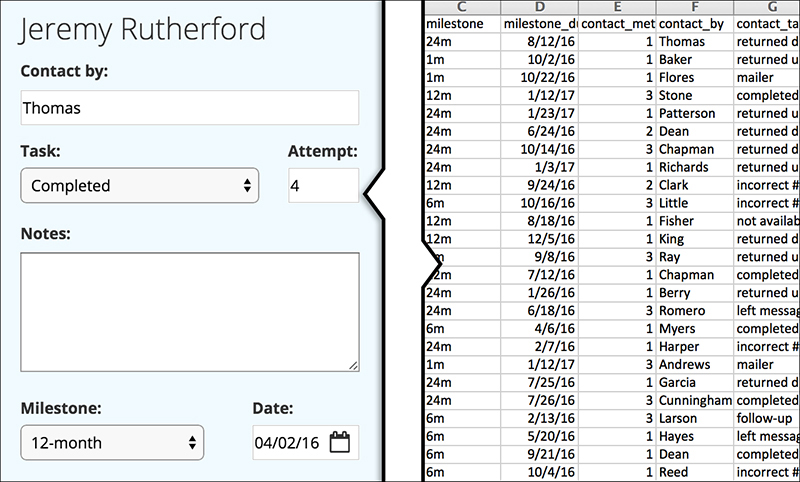

Another project I worked on had a complicated series of forms that were presented to the user as multiple steps. Each form could be different based on the options chosen in the previous step. First, the user would enter some information about the people in the report such as name, address, height, and weight and then choose the next form. When the user chose the second form (the event category in the figure that follows), we decided it was best to take them to a completely new page without the whole app navigation because the forms were so complex. We wanted the user to focus on the task and not be distracted. On that second form, the user’s previously entered details were plainly visible at the top of the view.

When our client saw it, she said it was fine but the user needed to be able to edit the patient’s details on this second form as well as the first. I questioned this because the user had just entered that information. Why would they need to immediately change it? Her response was confusing: she went on a tangent about a paper government form she was used to filling out, she expressed that she didn’t want to train employees, that the details had to be entered correctly the first time, and that sometimes you might want two different addresses for the same person. Paper forms? Training? Duplicate data? None of it made any sense, so I pushed back.

This is a simplified version, but in my original design, the user moved horizontally from one step to the other, but my client expressed frustration at not being able to edit the information from Step 1.

For several meetings, she continued to insist that we allow the user to edit the patient details on the second form, until finally I began to realize that she saw this app as a digital version of the paper form she had mentioned earlier. I had indeed designed it to be similar and she was distracted by what she saw as the differences. After some tough choices, we decided that the second form would not load on a new page but would instead simply load inline on the page directly below where the user had entered these details. We moved from a horizontal progress status to a vertical one. It was effectively still the same, but not having to return to a previous step to see the information gave the user a greater sense of control.

In the final design, the user moved vertically, which gave my client a better sense of control over entering the data.

When she saw our solution, she agreed it was better and we moved on to the next design. Had we made the changes she suggested initially (allowing users to edit the same data in two places), it would have resulted in a host of other usability problems. Listening to her and working hard to uncover the real problem she was trying to solve helped to ensure that we maintained a better user experience.

In summary, the visual nature of design naturally lends itself to changes in those visuals in order to accomplish the desired result. People make suggestions on how to change those things rather than describe the problem they see. It’s hard for most people to think concretely about and express design problems. They only know that it doesn’t feel right. Consequently, we need to be adept at listening to their solutions and connecting the dots in order to uncover the real problem.

THE ART OF THE PAUSE

The right word may be effective, but no word was ever as effective as a rightly timed pause.

MARK TWAIN

One last implicit listening skill is mastering the art of the pause—when you think your stakeholders are done talking, just wait. Don’t immediately jump in with your response. Instead, pause for several seconds (maybe two or three) and allow for silence, however uncomfortable that might seem. This can actually be a little awkward, especially on a conference call or video chat where there are frequently delays and it might be difficult to tell if you’ve dropped off. (My own clients commonly ask if I’m still on the line, unsure if I was disconnected.) But whether you’re on a call or face-to-face, it’s worth risking the awkwardness to be sure that your stakeholder is finished talking and that there is a small gap in the discussion.

The purpose of the pause is threefold:

• First, you want to be sure they’re actually done talking and that they haven’t just paused themselves. Sometimes people stop and then immediately think of something else or a better way of saying it. If there’s a better way for them to give you their feedback, you will want to hear it, because people don’t always express it correctly the first time. Give them a chance to be articulate themselves. They need to feel good about what they said so they can’t blame a misunderstanding on poor wording.

• Second, it gives you a chance to let the air settle; to let your stakeholders’ words sit on everyone’s ears for just a moment. You’re letting the conversation simmer briefly, which gives you a chance to very quickly consider how to respond. You’re not jumping directly into a defensive posture, but instead taking a moment to consider what was said and form an appropriate response. Just these few seconds of waiting will make you much more prepared to respond.

• The third (and most important) benefit to pausing is that you communicate to the other person that what they said is important enough for you to really consider it and think about it. Because you didn’t jump directly to a conclusion that might conflict with theirs, you create a sense that what they just said was really valuable. People want to be heard (or at least to feel that they’ve been heard), and pausing gives you a chance to show them that you take their feedback seriously. If the silence is too deafening for you, say something like, “I hear what you’re saying. Let me think about that for a second.”

All of these implicit listening skills should establish a framework for how you see and hear your stakeholder’s feedback. As you listen to them, you’re making a conscious, nonverbal effort to truly understand what they mean. These internalized activities give you an opportunity to better organize your thoughts so that you can find the most effective response.

Explicit Activities

In addition to the internalized activities we use to listen to design feedback, there are also several explicit activities we can use to improve listening. Explicit listening includes verbally demonstrating that you’re listening as well as doing things that outwardly show you are engaged in the conversation. For design meetings, taking notes, asking questions, and repeating back or rephrasing what they say are all important ways to effectively listen to our stakeholder’s feedback.

WRITE IT ALL DOWN

The first thing you need to do to listen is to take notes. You’re not going to remember everything your stakeholders say or suggest. One of the best ways to listen to them is to write down what they say. Record everything, especially the items that need to be followed up on. Even in smaller meetings, it’s important to write down what was discussed and save it somewhere. I’ve already recommended writing things down and taking notes at different stages of the process, and you should always have a way to take notes in your meetings. You might never reference your notes after the meeting, but that’s okay. Taking notes is more than just having a place to record what was said:

Notes prevent you from having the same conversation again.

Taking notes is the only way you’re going to remember what was discussed and create a history that will help you to avoid the same conversations again in the future. I’ve found that a lack of notes is frequently responsible for miscommunications, repeat conversations, and changing requirements on many projects. Having notes avoids the rework that will prevent you from being successful in communicating about your designs.

When it comes to design, notes are critical because opinions and ideas about the right decision will change over time. If you don’t have notes, you don’t have a paper trail to understand what logic went into the original decisions. You only have “he said, she said” and a bunch of rehashed conversations. When design decisions are made verbally in a meeting, it can be nearly impossible to remember later why decisions were made. Additionally, there may be team members who aren’t present at the meeting. Having notes helps you to quickly bring them up to speed without recounting the entire meeting.

I am, admittedly, not the best at keeping my notes organized, but I do keep them, and there have been multiple occasions when we chose a path for a specific interaction that was called into question after the public release. “Hey, why did we do it this way?” I was able to find my notes from months earlier and follow up with everyone and even remind them of the person who suggested the change, why, and the date. When you can do that, it usually shuts down the conversation, saves everyone time, and allows you to move on. With detailed information like that, you can either address the problem and discuss a better solution or remember that the decisions were right the first time and move on.

Notes free you to focus on being articulate.

For the same reasons discussed in Chapter 4, writing things down reduces your cognitive load and frees your mind to focus on being articulate in your response. When it’s written, you no longer need to think about it. If you allow all their ideas and feedback to float freely through your brain, you’ll have a difficult time organizing those suggestions in a way that will yield the best response. Write down what they’re saying so you can take the next step and form your responses without needing to actively recall everything from memory.

Notes build trust with your stakeholders.

Another benefit to taking notes is that just the act of writing things down will make you look attentive, smart, and, as a result, more articulate. Taking notes makes you look like a good communicator. It makes the other person feel valued because you care enough about what they said to write it down. This gives them confidence that you heard what they said and you’re planning to follow through. When people have that impression of you, they do a much better job of listening to and considering your own response later. It’s a shared respect that goes both ways. As a result, I often use note taking as a way to tell people that I’m listening and bring out the best in the discussion even if I disagree with their suggestion. Verbally saying something like, “Oh, I see your point. Let me write that down,” earns trust and shows that you’re a safe person to talk to.

I don’t mean to suggest that you should write things down that you have no intention of following up on only to make the other person feel good. Taking notes can create a positive perception, but you shouldn’t be disingenuous. For instance, if I’m not sure I really want to do what that person is suggesting, I might write it down but leave a question mark next to it so that I can follow up later. Taking notes is more than just remembering what was decided. It has intrinsic value above and beyond what you will actually do with the notes after the fact.

Notes keep the meeting on track.

Writing things down is also a great way to ensure that your meeting stays focused by giving you a place to record parts of the conversation that get off topic. People will think of just about anything in a design meeting, and it’s easy for it to get derailed by something that isn’t the core focus.

Suppose that you’re showing the home page to discuss the interaction on the category menu, but when your boss notices that the login form is messed up, suddenly the meeting is headed in a different direction. Because you’re taking notes, you can suggest delaying the discussion of the login form if that’s not the purpose of the meeting. “Yeah, I noticed the login form this morning, too. Let me make a note of that and I will follow up right after this meeting, but for now let’s stay focused on the category menu.” Taking notes gives you a natural place to put stuff that might otherwise be distracting.

Writing things down feels more permanent than only saying it out loud. It gives everyone a sense of security that what’s being said was important and will not be discarded.

TAKING BETTER NOTES

The best way to take notes is to ask another person to do it for you. This frees up your brain to be focused on listening and being articulate. If you’re trying to write down what people are saying, you’ll miss important parts of the conversation because things can move quickly. If you don’t have the authority to tell someone else to take notes for you, find a note buddy who is willing to help. Offer to swap note taking responsibilities at each other’s meetings. It could even be someone from a different department or project, any willing person who can be trusted to capture the conversation. You might also consider recording audio or video of the meeting, but I’ve found that I rarely have time to review the video afterward to recapture lost notes. The best practice is to write down what people say so that you have an immediately accessible history to reference, even if you do it yourself.

To get the most of your notes from a design meeting, they should be:

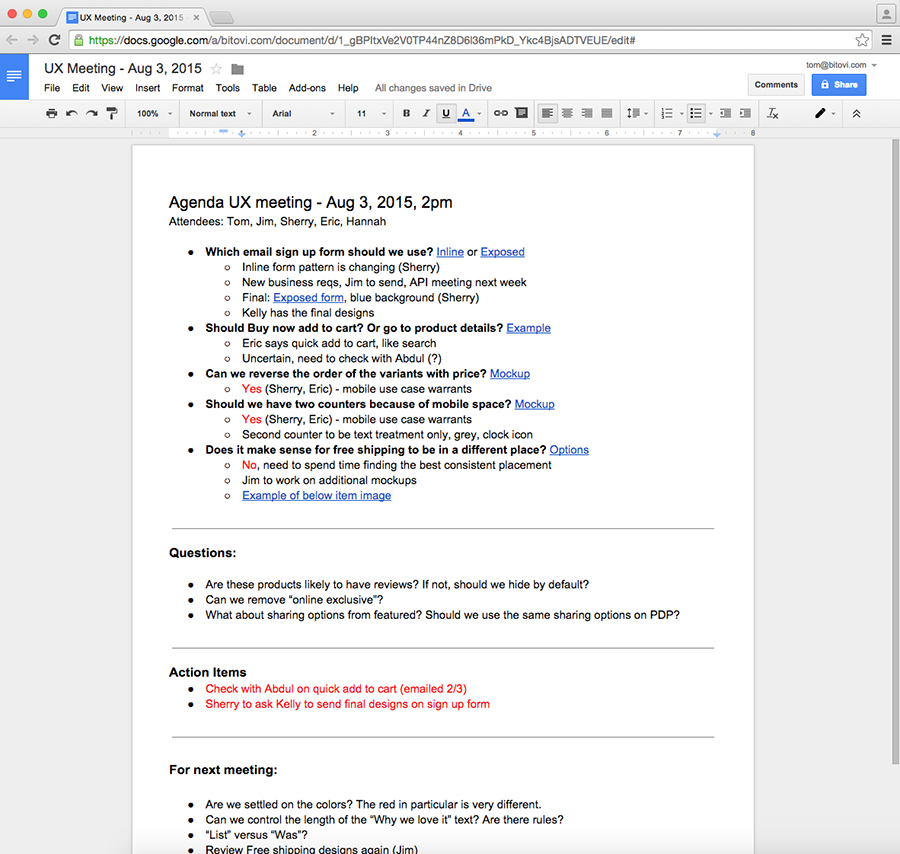

Accessible

Store your notes in a place that everyone can access. As we will see in Chapter 9, following up with your notes afterward is an important part of the process. Here in the meeting, you just need to be sure that everyone can see or has access to them. This might be a wiki page in your project’s repo, a separate page on your design mockups, or a shared folder or document. Your notes should always be available to everyone on the team, even during the meeting itself.

Organized

Write your notes within each agenda item so that it stays connected to the design in question. Usually, this would be by page, UI control, or interaction. Attach your notes to one specific thing. I usually create a bullet list of notes under each agenda item as the meeting progresses.

Specific

Write down the names of people who make the suggestion you’re noting as well as the names of people who agree or disagree. This is not always an exact science, but something as simple as “Cynthia suggests changing the color; Brian isn’t sure” comes in useful later when you’re trying to remember who was responsible for suggesting the change.

Definitive

When a decision is made, make that explicitly clear so that you can find it later if you need to remember it; for example, “Final: drop-down control should be a popover menu.” Items that are still undecided should also be marked so that you can follow up on them later. I add a question mark to anything pending a decision: “Reconsider placement of sort options (?)”

Actionable

Nearly every item should have a follow-up action or person associated with it. Writing down ideas is useful, but if there’s no action, there is almost no point. For example: “To do: update prototype w/new control,” or better, “Chad to update prototype w/new control.” If there is a lot of follow-up to be done, it might be useful to create a separate section in your notes just for documenting it so that you don’t miss it in the list of other notes. I often create a separate heading below the agenda called “Follow-Up.”

Referenced

Add links, URLs, screenshots, or other reference material to your notes so that it’s easier to communicate what the point of the discussion was. When people suggest other websites or apps as a reference, add that information to help you remember the conversation. Without references, it will be difficult to recall what you meant by “See how SocialApp does it.” Adding inline screenshots or URLs with the agenda makes your notes much more valuable in the long term.

Forward-looking

Aside from the agenda items that you need to cover right away, there are always other design decisions that will come up during the course of the conversation. You need a place in your notes to add items to be discussed at the next meeting, or in a different context. I do this by simply adding a new heading in my notes called “Next Meeting.” Having this real-estate set aside gives me a place I can quickly organize discussion that might be off-topic and note it for the next time around.

To summarize, taking notes is a critical part of listening to stakeholders. It’s important to write things down so that we have a history of what was decided and avoid having the same conversation twice. But notes are more than just a place to record our decisions; they also allow us to focus more on being articulate in our response because we no longer need to rethink everything that was said previously. With our notes in hand, it’s much easier to go through each piece of feedback and prepare the best response. Regardless of the size or importance of the meeting, always take notes.

I don’t always take good notes, but when I do, they’re Accessible (Google Docs), Organized, Specific, Definitive, Actionable, Referenced, and Forward-Looking!

ASK QUESTIONS

The challenge with talking about design to stakeholders is that they often don’t know the best words to communicate their meaning. In the same way that we designers have difficulty expressing our decisions to them, they, too, have difficulty expressing their own thoughts to us. Yet, so much of listening is just about getting the other person to talk. We need to pull the words out of them that will help us do our job better. It’s not usually enough to just let someone to say their piece and then move on. Some people will have plenty to say that is difficult to interpret, whereas others won’t have much to say at all. We need to get them talking more, to say it in a different way, and to express their thoughts more carefully. The way that we do that is by asking good questions.

Here are a handful of common questions that are useful to ask in any situation to get people talking more and help you to understand their suggestions or feedback:

• What problem are you trying to solve? Like the previous section, it’s okay to be direct if it’s not clear what stakeholders are trying to accomplish with their suggestions. Just ask them outright.

• What are the advantages of doing it this way? This gives stakeholders a neutral way of explaining why they think their suggestion is better without explicitly labeling one as better than the other. Giving them a way to express these differences will reveal a lot about why they think it’s the right solution.

• What do you suggest? Often stakeholders will say something needs to change without any idea about how that will be done. Even though it’s our job is to find the solution, giving stakeholders an opportunity to propose something helps us understand their needs and gives them some context to realize the difficulty of the problem.

• How will this affect our goals? Stakeholders often have our goals in mind, but they don’t always realize how what they’re saying is connected to them. You want them to directly connect your designs to the goals every time. Often, just the process of answering this question helps them see why their suggestion won’t work as well as they thought.

• Where have you seen this before? Asking for reference material (other apps and websites) is one of the best ways of seeing your stakeholder’s perspective. The point isn’t to suggest that their idea won’t work if it doesn’t exist already, but to find out if it’s rooted in a known design pattern from some other app or website.

The main purpose of asking questions is to get your stakeholders to explain what they mean so that you can be sure you understand. Asking questions also has benefits beyond simply getting the other person to clarify what they mean. Even if you already understand what the other person is trying to say, asking good questions shows that you’re listening. By repeating back to them what they said in your words and in the form of a question, you’re reinforcing that you understand. This creates more trust. The other person feels respected, valued, and understood. Just like letting them talk, they’re much more likely to agree with you later when they feel good about being heard now.

REPEAT AND REPHRASE

The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms.

SOCRATES

The words we choose to talk about our designs can make or break the conversation. If we aren’t using the same vocabulary to talk about our work with other people, there will inevitably be misunderstanding, confusion, and missed expectations along the way. Our stakeholders don’t always know or use the same words that we do. Finding that common ground is a balancing act of meeting them where they are, while also helping them take steps in the right direction by teaching them to talk about design. If we’re going to agree on a solution, we need to get everyone using a shared vocabulary that facilitates understanding. Part of listening is identifying the words our stakeholders use to describe our designs and then repeating it back to them in way that helps everyone get on the same page.

Rephrase: Convert “Likes” to “Works”

The most important way we can do this is to help our clients move from talking about what they like and don’t like (which are their preferences) to what works and what doesn’t work (which is the effectiveness of the design). It’s too easy for someone to say they simply don’t like something. A subjective response like that gives us no way to address our stakeholders’ concerns because it’s not possible to tell them their opinion is incorrect. We can only have a different opinion.

Instead, listen for opportunities to convert “likes” into “works.” Repeat back what they said by rephrasing the statement to focus on effectiveness. You might also consider following up with a question to confirm that’s what they intended to communicate or for additional clarification. For example, “I understand that you want us to move that UI control over there, but why doesn’t it work to have it over here?” When people hear their concerns rephrased inside a frame of effectiveness, they often recognize that they’re only expressing a personal preference. You might still have to deal with managing their request, but at least we’re getting to the core issue and understanding how to respond to them more intelligently.

This doesn’t mean we should teach our stakeholders, correct them, or send them a copy of Chapter 12 for homework. (Although the latter wouldn’t be a bad idea!) What we should do is rephrase their response in the form of a question that forces them to talk about it in a way that’s more helpful. If you’re not sure, ask them directly. Encourage them to tell you what doesn’t work about your design. This means that you, too, must work hard to strike the word “like” from your vocabulary and always place an emphasis on the utility and function of the design.

Getting our stakeholders to move from discussing their preference to describing the function of the application is a key skill in the process of articulating design decisions. The reality is, we don’t really care about what our stakeholders like or don’t like (although we could never tell them that). With a user-centered design approach, we’re concerned with what does and doesn’t work for the user and ultimately for the business. Flipping this switch in the minds of our stakeholders can make a big difference in our ability to communicate.

Repeat: What I Hear You Saying

Another way to train our stakeholders to communicate more clearly is by repeating back to them what they said using words that are more relevant to a discussion of design and UX. Because we don’t expect that they’ll know all the “right words” to describe our designs, we have to listen to what they’re saying and translate that into a vocabulary that will become our common ground. Leading with the phrase “What I hear you saying...” is the best approach to accomplishing this because it emphasizes that we are listening to them, understand what they said, and will now confirm it by expressing it in our own words. This is an opportunity to bridge the language gap: take what they said in their own words and translate it into something that will be more helpful in the design decision-making process.

Here’s an example:

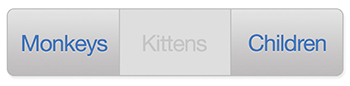

Stakeholder: I don’t like how these disabled buttons look. I have no idea why they don’t work! We should add some help text or a tooltip or something.

Designer: What I hear you saying is that you don’t think a segmented control is the best choice in this context, because the user won’t understand why the disabled options aren’t available to them. Is that right?

Why aren’t kittens available? Teaching our stakeholders to call this a “segmented control” without talking down to them can be useful in moving toward a shared vocabulary.

Repeating what our stakeholders say, using terms that will be more helpful to the conversation, is a great step toward a common language without coming across as overtly condescending or alienating them for using the wrong words. You need to find the right balance of helping them without making them feel silly.

This is actually something I’ve learned with my kids. The best way to teach them is not to correct them directly, but to repeat back what they said in the correct way. When my child says, “Gimme that big red thingy,” it’s much more effective to respond, “Oh, you’d like this measuring cup?” than it is to say, “Silly child, this is a measuring cup! And ‘thingy’ isn’t even a real word! Ask for it using the right words and then I’ll give it to you.” My child isn’t ignorant. She just lacks the vocabulary to describe what seems to me like everyday objects. Our stakeholders aren’t to be treated like children just because they don’t use the same words we do. Instead, we can help them be more effective by repeating back to them words that are more useful.

Here are some examples of how you might craft your responses in a way which introduces stakeholders to a shared vocabulary:

Stakeholder: That button needs to be moved over here.

Designer: We purposefully placed the call to action above the fold.

Stakeholder: That arrow is too difficult to see.

Designer: The disclosure is meant to be subtle so it doesn’t distract from the content.

Stakeholder: This menu is hard to use.

Designer: We’re using the system’s native droplist, but we could design a custom control.

Remember that an important part of listening is rephrasing and repeating back what our clients have said so that we can confirm we’re on the same page and have a solid understanding of the best way to respond.

Let’s review what it looks like to listen to stakeholder’s design feedback. We cannot communicate effectively with them unless we listen to them and fully understand what they’re saying. There are several implicit ways we listen, such as letting them talk as much as they need to, trying to hear what isn’t being said, and working to uncover the real problem they’re addressing. After that, pause for a few seconds to be sure they’ve finished talking. But there are also several explicit skills we can apply to be better listeners of design feedback. We take good notes by writing down what was decided. We ask questions to clarify and tune our understanding. And we repeat and rephrase what stakeholders say to help establish a shared vocabulary and common ground. All of these things help us be better listeners, understand what is being communicated, and allow us to form the best response. You might think it’s time to tell them what you think now, but it’s not. First, we need to get in the right frame of mind.