Chapter 7. Prototyping

Explore, challenge, and evolve your ideas in reality.

Expert comments by:

Alexander Osterwalder | Carola Verschoor | Francesca Terzi | Johan Blomkvist | Kristina Carlander

7.1 The process of service prototyping

-

Prototyping service processes and experiences: Investigative rehearsal

Prototyping service processes and experiences: Desktop walkthrough

Prototyping physical objects and environments: Cardboard prototyping

Prototyping digital artifacts and software: Rehearsing digital services

Prototyping digital artifacts and software: Paper prototyping

Prototyping digital artifacts and software: Interactive click modeling

Prototyping ecosystems and business value: Service advertisement

Prototyping ecosystems and business value: Desktop system mapping (a.k.a. Business Origami)

Prototyping ecosystems and business value: Business Model Canvas

-

7.3.3 Case: Enabling staff and stakeholders to prototype for continuous evolution

7.3.4 Case: Minimum lovable products, living prototypes, and high-fidelity sketching in code

7.3.5 Case: Using role-plays and simulations in large-scale 1:1 prototypes

7.3.6 Case: Using multifaceted prototyping to create and iterate business and service models

This chapter also includes

Reducing Uncertainty

In service design, prototyping is used to explore, evaluate, and communicate how people might behave in or experience a future service situation. Prototyping helps the design team to:

→ Quickly identify important aspects of a new service concept and explore different alternative solutions.

→ Systematically evaluate which solutions might work in our everyday reality.

→ Effectively create a shared understanding of initial ideas and concepts, enhancing communication, collaboration, and participation of interdisciplinary stakeholders.

Prototyping is an essential activity to reduce risk and uncertainty as early and as cheaply as possible, to improve the quality of your final deliverable, and to eventually implement your project successfully. Usually prototyping is done after some initial research and ideation in a service design project, but it can also be used to kick off a project, especially when working on existing products. Prototyping activities often uncover new questions and send the team back to research or ideation, which leads to even more options you might decide to prototype and test.

Comment

Comment

“One of the key challenges in service prototyping is the constant interplay between prototyping of single touchpoints vs. consistent and iterative development of holistic service experiences.”

— Johan Blomkvist

By turning your ideas into prototypes and testing them with real customers and stakeholders in realistic contexts, you keep your personal biases 1 in check. Through prototyping you produce work which is grounded in reality, not in assumptions and opinions.

Practically, over the course of a whole service design project you will use a wide range of methods, from quick-and-dirty prototyping to simulating and testing close-to-reality prototypes that deliver solid and valid (market) data. Prototyping is a structured but in itself iterative process. It often starts with exploring a simple idea or question and leads to iterating between working on specific parts of the service and exploring the effects of those changes on holistic end-to-end experiences.

Service prototyping uses walkthroughs, theatrical rehearsals, or process simulations as well as traditional model making and testing techniques from a wide range of disciplines. While the scope of prototyping in service design might vary, it should always balance holistic perspectives across multiple steps with a detailed focus on single touchpoints or experiences. You employ ethnographic research methods to evaluate and make sense of the gathered data. In many ways – especially when used for explorative and validating purposes – service prototyping can be seen as research focused on future service situations.

THE BASIC PROCESS OF SERVICE PROTOTYPING

Figure 7-1. Prototyping activities are embedded in an iterative sequence with other activities of research, ideation, and implementation.

Research-based: The creation of the prototype itself is only the starting point which allows us to focus on using and testing prototypes and learn from them.

Iterations and prototyping loops: Prototyping is an iterative process with a sequence of prototyping loops. The challenge is to find a balance between prototyping the details of a single (inter)action, object, or app and the wider end-to-end experience.

The Process of Service Prototyping

Introducing an actionable framework for service prototyping

Compared to prototyping in other (design) disciplines, the prototyping of services or product experiences is more holistic. It starts with the wider context of how services and physical or digital products 2 are experienced and used, but also encompasses traditional prototyping work on key assets like (physical) products, software, architecture, or actual content, making it more complex to work with. This chapter presents an actionable framework for service prototyping in practice.

Just like any other core activity of the service design process, prototyping 3 can benefit from a clearly articulated design. Even though not every prototyping activity needs extensive planning, the following framework might help you to achieve richer results with fewer resources. It doesn’t need to be followed step by step, but provides a collection of useful principles that you can apply to your prototyping efforts.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Don’t underestimate the energy factor in prototyping. It is highly stimulating to create tangible artifacts and to see quick results. It opens up stimulating conversations; it creates passion, pride, and ownership; and it attracts internal attention, sometimes also external. Prototyping pushes a team and an organization forward. These may look like positive side effects, but should be seen as important reasons in themselves.”

— Kristina Carlander

Decide on the purpose

Your first step in prototyping is to clarify your purpose: Why you are prototyping and what you want to achieve. There are three main reasons why prototyping is used in service design: to explore, to evaluate, and to communicate. 4 Be aware that this is not a strict distinction and often the activities can be mixed – to some degree even within a single prototyping session.

Prototyping to explore

Explorative prototyping (or prototyping to explore) is used to create new options and new future solutions based on a given initial service concept or idea (or a previous prototype). Think of it as a form of ideation, or “thinking with your hands.” You learn more about the opportunities and the challenges of the solution space.

Figure 7-2. Prototyping is used to explore, evaluate, and communicate at various stages in the process.

Explorative prototyping is mostly done for yourself or the core project team. 5 Prototypes are created in parallel to quickly compare different options and perspectives. Explicitly, they are built to be thrown away, so you might want to use prototyping materials or platforms that are geared toward creating prototypes fast. Early in the process, these are typically things you have lying around your workspace already. Explorative prototyping creates many insights, new questions, and hypotheses about how a future service might create value, might work, or might feel. 6

Comment

Comment

“We use prototyping sessions instead of traditional idea generation on sticky notes when we start working with highly interdisciplinary teams. Every one of them has their own specialist jargon and this leads to many misunderstandings. Prototyping is the universal language that helps them to understand each other much faster.”

— Francesca Terzi

Prototyping to evaluate

Evaluative prototyping is used to understand how people experience the future that our prototyping suggests. Sometimes you will carefully evaluate your hypotheses in formal testing, and sometimes you will do more lightweight tests on the fly. 7 Whether formal or informal, evaluative prototyping helps you to converge again, to start reducing the number of options you have and decide what to focus on. Evaluative prototyping sessions are created with a specific set of questions or hypotheses in mind that need to be tested. Prototypes are often built for potential customers or other carefully selected stakeholders from outside the team. 8

During formal evaluative prototyping, you strive to create prototypes that mimic aspects of reality as closely as possible. If you are interested in the emotional responses to a service (or part of a service), you must let the customers experience it. For the evaluation part, this form of prototyping is heavily supported by qualitative research and analysis methods that can provide some hard facts and metrics, such as contextual and in-depth interviews as well as various forms of observation.

Prototyping to communicate and present

Communicative prototyping is used to communicate important aspects of your project to selected audiences. Specifically tailored prototypes and prototyping activities help you to reduce misunderstandings and ignite meaningful discussions around the key design questions within the team or organization, or with other stakeholders. This facilitates collaboration, supports decision making, and reduces friction in your project right from the start. Different personal perspectives and potential conflicts become clearly visible and can be openly addressed. In addition to creating a safe space for experimentation, these activities are a great tool for team formation.

Comment

Comment

“If a picture is worth 1,000 words, a prototype is worth 1,000 meetings.”

— @johnmaeda 9

For a wider audience, presentational prototypes can be used as props for well-rehearsed storytelling presentations. In those cases there is little to no interactivity of the audience with the prototype. 10 The prototypes are adapted from previous prototyping activities and are usually quite polished. Used with care, presentational prototypes are a valuable strategic tool to present, persuade, and inspire management or key stakeholders.

Decide on your prototyping questions

At each iteration, you need to clearly state what you want to learn or achieve through your prototyping activities by formulating one or many prototyping questions. Think about these prototyping questions as the research questions 11 of the prototyping stage. In our prototyping work, we have found value, look and feel, feasibility, and integration to be especially helpful perspectives in generating initial prototyping questions and focusing on key aspects of a service concept during prototyping. 12

As Stephanie Houde and Charles Hill point out, “prototypes provide the means for examining design problems and evaluating solutions. Selecting the focus of a prototype is the art of identifying the most important open design questions.” 13 By formulating one or many prototyping questions you make sure that your team (and your potential client) have a common prototyping aim.

Start with a value prototype

Value prototypes are often a great start. Usually it is easier to find a suitable technology or business model if you already have a strong value proposition than the other way around. Be aware that look-and-feel and especially technical feasibility prototypes can take a lot of time and effort to create. This is easily wasted if the value proposition is still changing rapidly. You can spend a lot of effort and money creating a great look and feel, but if you don’t build it on top of a solid value proposition that is backed by research or prototyping, you are very likely to burn money.

Assess idea and project context

Keep in mind that your actual starting point always depends on your individual project. In the fashion industry, look-and-feel prototyping will get more focus than in B2B business consulting, where there is a stronger focus on value. In projects where a specific technology stack has to be used, feasibility prototypes should be given a higher priority as they define the playing ground for many solutions. Your decision will also depend on whether the project needs to deliver immediate results or is used to explore innovative future solutions as inspirations for future developments – like concept cars in the automotive industry.

VALUABLE PERSPECTIVES TO IDENTIFY PROTOTYPING QUESTIONS

Iterate

As you move forward, iterate between value, look and feel, and feasibility on one side and integration prototypes on the other to make sure you are not wasting time and effort on concepts that might not work in the implementation context. Identify dependencies between the different aspects early and learn how to integrate them into your design. Staying with value prototypes for too long tends to result in concepts that are hard to implement – which makes it challenging for short-term projects. On the other hand, this might be spot on when you are looking for inspirational concepts as a guidance for future work.

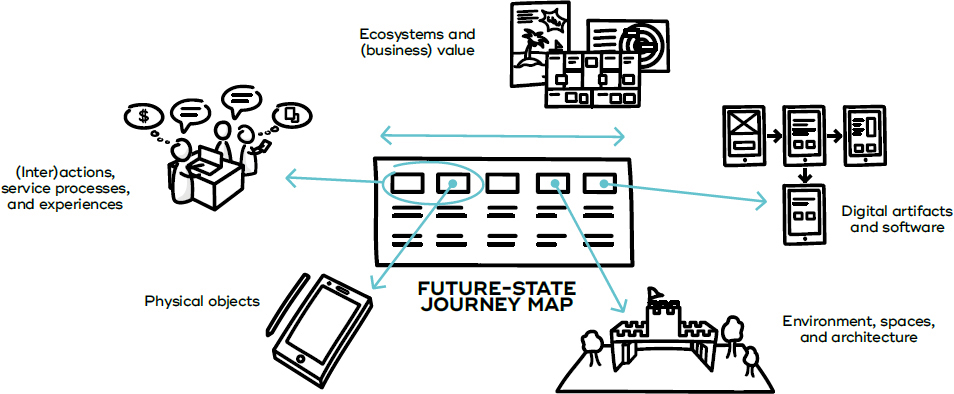

Figure 7-3. COMPONENTS OF PROTOTYPING

Future-state journeys are a great first step in assessing what you need to make or build in order to answer your prototyping questions.

Assess what to make or build

It can be helpful to first assess which parts of your future services and physical or digital products you actually need to make or build in order to get the answers you need, and then get concrete. Future-state journeys of customers or key stakeholders are a great first step. 14 Often, this allows you to break your prototyping challenge down to a mix of the following major components:

→ (Inter)actions, service processes, experiences

→ Physical objects

→ Environments, spaces, architecture

→ Digital artifacts and software

→ Ecosystems, (business) value

For some prototyping questions this can be straightforward. If for example you are working on a new home automation system, your questions about hardware and software might suggest that you build a functional prototype of a piece of software together with a physical prototype of an internet-enabled gadget.

However, more complex questions – for example, whether your home automation service actually creates a meaningful value for your customers and makes them happier people – cannot be answered directly.

In this context, experiences with services or products, whether physical or digital, can be likened to an (interactive) theater play. While theatermakers cannot design the emotions of an audience directly, there are things they can do. They can create a compelling story, write gripping dialogue, create great costumes and stage design, develop systems and technologies for special effects, and rehearse with actors and staff (front- and backstage). They can keep doing this until they can deliver an engaging interaction that evokes the emotional response and creates the value they are striving for in both the actors and their audience.

Prototyping tackles the same challenge with the same basic approach. We cannot design the actual experiences of our future services and physical or digital products directly, but we can design and prototype many concrete aspects around them to gather valuable feedback and other data from the people involved.

However, since it is usually impossible to prototype every aspect, you will need to make a decision about which aspects are most important. One way to do this is to use a prototyping portfolio (based on an idea portfolio) to discuss and prioritize the parts and elements of your service that you want to explore, evaluate, or communicate through prototyping. 16

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Prototyping is serious business, that should be used systematically and may require a notable amount of planning. But don’t forget the ability to quickly create lo-fi prototypes of your ideas, also in later stages. You will learn a lot just by taking a step from thinking to doing. If you get stuck in a discussion, a simple role-play (acting out the problem) may in that moment suggest the solution you need. And that role-play is also a prototype others can react to. Nurture a prototyping culture!”

— Kristina Carlander

Planning prototyping

When planning your prototyping activities, you should think of the ways that are most likely to give you fruitful answers for your proposed design questions within your chosen purpose and goals. Just like anything else you do, prototyping activities must fit within certain business constraints, as you always have to consider how to best allocate time, money, and human resources within a project. Specifically, prototyping planning includes decisions about audience, authors, fidelity, context, prototyping loops, multitracking, and method selection. We’ll explore them further here. 17

Audience

Like in research, you have to think about your sample: 18 Who will be experiencing or testing your prototypes? Who do you want to observe? Who should participate in your prototyping sessions and how do you select them? These questions are critical for the reliability of what you are going to learn during prototyping and how valid the results will be. Use stakeholder mapping to get a clear picture about the sampling strategy for your prototyping activities. 19

In prototyping you will typically move between different groups of stakeholders acting as your audience: e.g., members of your project team, colleagues, current staff, internal/external experts, clients, (potential) users, customers, and future staff. 20 As a rule of thumb, the closer people are to the project team the easier (and faster) it gets to recruit them for your prototyping sessions. However, you will find stronger bias in those groups than with people from outside. Of course, your goal should always be to show your prototype to actual users and customers as soon as possible. 21

Roles in the team

While the audience has a huge impact on the outcome of the prototyping activity, so too do the people who drive the prototyping process, who prepare and build the prototypes, run the sessions, and observe the reactions of the chosen audience. 22 Typical roles in prototyping activities include:

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Nurture a sustainable prototyping process. Some of us work with services as a project, which has an end. But the service should be continuously tested and improved. Provide the staff with training and easy-to-use tools and formats for prototyping. Prototype together, to make it easy for the staff to continue prototyping when the project is over.”

— Kristina Carlander

→ Concept owner: The concept owner is the person who came up with the concept you are prototyping.

→ Writer or (model) maker: The writer scripts or sketches out a starting point for the experiences, (inter)actions, or scenarios that you are going to prototype. The (model) maker builds all necessary (physical and digital) props, sets, and stages for the prototyping session. 23

→ Facilitator: The facilitator is responsible for the process and guides the selected audience through a prototyping session. 24

→ Actors and operators: Actors and operators assist the facilitator in creating an experience during the prototyping session. This involves people acting as staff or other customers during service simulations, or manually operating an interface that is tested. When preparing your prototyping sessions, always ask yourself: Who will be taking on which role during the prototyping process? What are the biases and motivations each person brings to the table?

→ Researcher: The researcher independently observes the audience during the prototyping session and records her insights.

→ Subject matter experts and key stakeholders: Subject matter experts and key stakeholders complete the prototyping team, adding special skills and in-depth knowledge about the subject matter and target contexts suggested by scope and prototyping questions.

Note that especially early in the project, one person can be concept owner, maker, facilitator, and researcher all rolled into one. Later, when you have a clearer picture of your service concept, you might make the decision to involve specialists for each necessary craft or discipline (e.g., model makers, UX specialists, experience directors, ethnographers, etc.).

Always be aware of your role, bias, and associated influence on the audience at every step of the prototyping process. For example, concept owners and makers often want their concept to survive – consciously or unconsciously – because they have already invested some time into the concept or prototype. This obviously has an influence on the audience, and the results become biased. 25 One way to tackle this prototyper bias is to be open about your role and acknowledge that there is a bias. This lets you consciously put down your concept owner or maker hat and take a more objective position. Other options include inviting an independent facilitator or researcher for your testing sessions, or changing roles within the existing team between iterations.

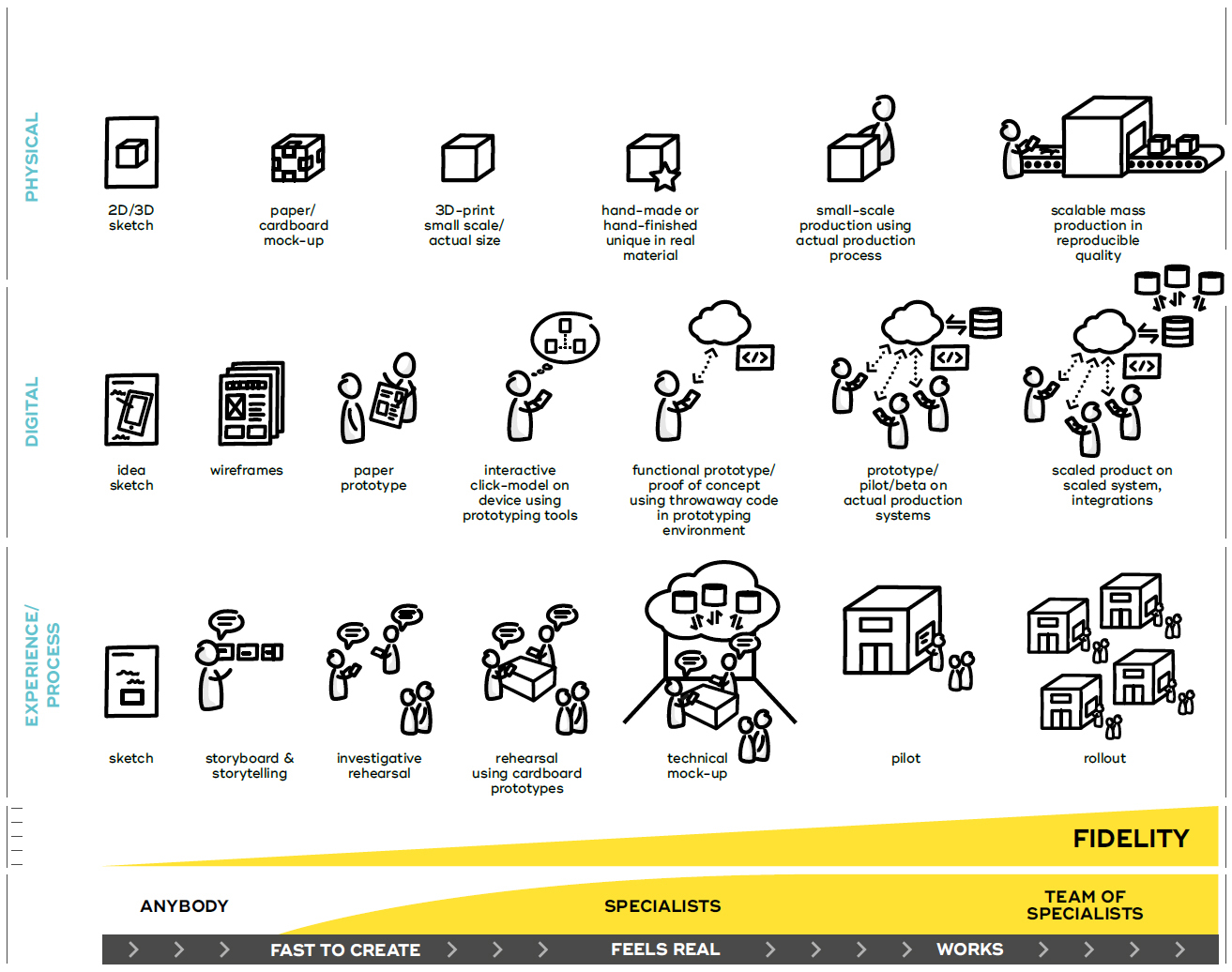

Fidelity

Decide how refined your prototype needs to be. What level of detail is needed? What resolution does it make sense to achieve for your given scope and research question? How much effort do you need or want to put into this prototype? The question of fidelity is closely connected to the economic principle of prototyping by Lim, Stolterman, and Tenenberg: “The best prototype is one that, in the simplest and most efficient way, makes the possibilities and limitations of a design idea visible and measurable.” 26

The economic principle seems to suggest starting with low-fidelity prototypes like paper or cardboard prototypes and then gradually increasing the level of detail as you get closer and closer to implementation. However, the world is slightly more complex than simply dividing the prototyping world into lo-fi or hi-fi.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Keep your first canvases rough and dirty when you use the Business Model Canvas to sketch out business models for new ideas or ventures. Then immediately test your early canvases in terms of desirability (will customers want it?), feasibility (can I build it?), and viability (will it be profitable?). Adapt your canvases rapidly based on what you learn from your tests. Iterate and refine your canvas with this so-called Lean Startup approach until you have sufficient evidence that your idea can succeed.”

— Alexander Osterwalder

While fidelity is often connected with visual fidelity (look and feel), you can also talk about fidelity in other dimensions, like fidelity of the implementation. 27 You can even find those different levels within one single prototype. The prototype of a website can be low fidelity with respect to look and feel, but quite high fidelity with respect to content or information structure. Hence, try to be specific about which parts of your prototype are really needed at which level of fidelity. This will help you manage your prototyping resources efficiently. It also is a great tool to guide the attention of your audience.

It is important to understand that the fidelity of your prototype has an impact on the quality and type of feedback you get from your test audience. Low-fidelity prototypes tend to inspire more open discussions while high-fidelity prototypes seem to lead the discussion more to the details of a concept because the prototype looks finished – and therefore decided.

Low-fidelity prototypes usually allow you to work blazingly fast. However, if you put too much emphasis on speed and low fidelity, your prototypes become meaningless. Try to find the sweet spot – the lowest meaningful fidelity at any given time – and move to high fidelity when you really need it.

The right fidelity for your prototype also depends on where you are in the process and what your purpose is. Earlier in the process, especially during explorative prototyping you would lean toward lower fidelity, while later in the process or during evaluative and communicative prototyping you usually lean toward higher fidelity. However, this needs to be reassessed for each project on an individual basis. Value prototypes like a service advertisement – which can be done quite early in the process – can already show high fidelity in a few essential perspectives (e.g., the value propositions), even though the rest of the business model is still quite raw.

In any case, always make sure the fidelity fits your audience. For example, people new to prototyping approaches usually need higher-fidelity prototypes together with clear guidance on purpose and scope. On the other hand, also make sure you are not over-promising. High-fidelity prototypes often are perceived as “finished” even if the underlying concept is still raw and basically untested.

Prototyping context

Choose the environment and context in which you run your prototyping sessions carefully. There are two major approaches:

→ Contextual prototyping: Contextual prototyping happens where the final service or product, whether physical or digital, would be used or be produced – for example, in the actual shop, tourism destination, or in one of your own offices where you run your consulting practice. By doing the prototyping session in context you can very efficiently assess whether or not a prototyped solution is a fit for that context or not. You also quickly learn what might work and, especially, what might not work. Just as in contextual research (e.g., contextual interviews, participant and non-participant observations, work-alongs, self-ethnography, etc.), you get a much better feel for the nuances that are needed to implement a working solution. 28

→ Lab prototyping: Lab prototyping is done within the safe confines of a lab environment or any place that is out of context. Choose lab prototyping when the real context is not available to you, does not allow any changes, does not exist yet, or simply is too expensive to use.

Figure 7-4. DIFFERENT FLAVORS OF FIDELITY

Fidelity comes in different flavors depending on what you are prototyping. While it is often connected with visual fidelity (look and feel), you can also talk about fidelity in other dimensions, like fidelity of the implementation.

It is important to note that context can include not only the space or location but also the time when you are prototyping, the availability of key resources, or even environmental conditions. For example, prototyping new hospitality services for a winter sport destination in winter can be contextual, while to test the same activities in summer you will have to fall back on lab prototyping.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Even if you have only a limited budget, do your best to stretch the scope to allow at least a few iterations, to make use of the learnings from the prototyping. It is better to make a few less ambitious prototypes than a bigger one-shot prototype.”

— Kristina Carlander

As a rule of thumb, the closer your prototyping environment and contexts are to the intended implementation contexts, the more reliable feedback you will get during evaluative prototyping. Similarly, during explorative prototyping, ideas generated in similar contexts tend to be more transferable from the prototype to the intended implementation context. 29

Prototyping loops

Always plan prototyping as an iterative process with a sequence of prototyping loops. Each loop should have a clear purpose; a clear set of prototyping questions; and include (a) building or preparing a prototype, (b) running the prototyping session, as well as (c) at least a simple form of data synthesis and analysis. The first loops are often explorative and might only take a couple of hours or a day. Use them to open up and create a shared understanding of the opportunity space. After those first loops, you might want to validate the proposed value propositions before eventually moving toward systematically exploring and validating the different aspects and dimensions of the selected concepts further and further. Continually check whether the chosen methods deliver meaningful results and whether your hypothesis or research questions for the prototyping stage need adjustments.

Depending on the skill set of your prototyping teams, you might have to involve specialists and split the work into separate work streams to achieve higher fidelity – for example, UX designers working on improving an existing app, service designers prototyping human-to-human interactions or required business processes, and an architect redesigning the office space. Even though they will work at different iteration speeds, it is still important to plan in regular sessions (e.g., weekly or biweekly) to give feedback and to adjust the prototyping plan. Depending on the complexity of your prototypes, you might also want to consider establishing a first sprint-like structure. 30

Keep iterating between the details of a single (inter)action, object, or app and the wider picture of the end-to-end experience.

Comment

Comment

“Just as there is theoretical saturation in design research, there is practical saturation in prototyping. Prototyping is great to help us understand by doing. At each iteration, you pivot into a new version by integrating the learnings of the previous version of the prototype. However, when any new learnings or insights have no significant or meaningful impact on the next version of your prototype anymore, you have effectively reached practical saturation. You are now ready to move on to the next phase on your service design journey.”

— Carola Verschoor

Multitracking

Decide how many prototypes you want to work on in any given segment. Multitracking your efforts helps you to reduce risk by not putting all your eggs into one basket. It also allows you to strategically manage uncertainty in your concept portfolio and expectations of stakeholders:

→ How many of the prototypes seem to be in reach for a quick win?

→ How many of them seem to have potential mid/long term?

→ How many of them are lined up for a disruptive breakthrough?

→ How many of them are a shot from the hip? 31

Also, decide whether you want to have different teams working on individual prototypes or have one team sequentially work through them.

The prototyping stage consists of a number of exploratory or evaluative prototyping sessions that can be lined up in parallel or in sequence. At certain points, you might add communicative prototypes to involve external stakeholders.

Method selection

Reflect on your chosen scope (including which elements of the service need to be prototyped), fidelity, and target context and choose the methods for your prototyping activities accordingly.

A helpful starting point is to do a quick assessment of the resources you have at your disposal. Before spending too much effort on creating complex prototypes, you might want to do some quick desk research 32 to find existing prototypes or research on similar questions or an appropriate prototyping platform you can leverage. Are there any elements you can simply reuse? Ask your Innovation department if they have already done something similar.

Desk research might quickly reveal similar services or products, whether physical or digital, which you can use as a basis to create your own prototypes so you do not have to start from scratch.

When you are selecting the “right” prototyping methods – ones that give you a lot of useful data, support your decisions, or communicate the concept well – you always face the question of how many methods you should use. Given a limited budget, you need to decide whether you should put all your budget into one method and do this rather well, or distribute our budget to use a variety of prototyping methods. Just like in research, you should also apply the concept of method triangulation during prototyping. 33

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“It is easy to like a prototype, even a mediocre prototype of a mediocre idea, as long as it addresses and solves an important problem in some way. It is therefore valuable to challenge one prototype with another, to make sure to get the best ideas. Therefore, make different prototypes, representing different ideas or directions of your idea. It is often valuable to stretch different directions to extremes (more or less), to provoke and learn rapidly. This is mostly relevant in early stages, where lo-fi prototypes are cheap to do and test.”

— Kristina Carlander

As a rule of thumb, you might want to consider to including at least one method from each of the following categories:

→ An experience prototyping approach to validate the core value proposition.

→ Some methods that allow the exploration and assessment of a holistic/end-to-end perspective on the service, like desktop walk- throughs, contextual walkthroughs, Business Model Canvases, Business Origami, minimum viable services/products or service simulations, and so on.

→ Some methods that focus on key elements within the holistic perspective, like paper prototyping, cardboard prototyping, digital mock-ups, and so on.

Figure 7-5. OVERVIEW OF PLANNING COMPONENTS

The planning of prototyping includes making decisions about audience, authors, fidelity, prototyping context, prototyping loops, multitracking, and method selection.

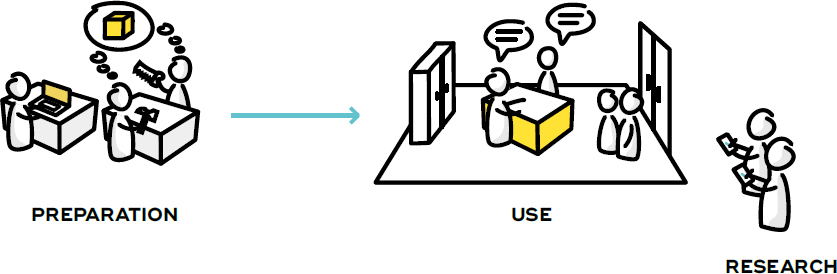

Figure 7-6. Running prototyping sessions: preparation, use and research. The creation of the prototype is only the starting point, which allows us to focus on using and testing the prototype and learning from it.

Running prototyping sessions

Prototyping methods share an underlying common structure. Any prototyping method can be broken up into the following three core activities:

→ Preparation: Prepare prototypes through setting up templates or canvases, scripting and practicing an intended interaction or walkthrough, making physical models, building stages/sets, and/or preparing environments.

→ Use: Use the prepared objects and practiced activities to explore, evaluate, or communicate a design concept.

→ Research: Use research methods while running the use scenarios to capture feedback, data and generate insights.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Make sure you do not get stuck on solving problems that only exist in your prototyping environment and not in the actual service system. Prototyping should be future oriented rather than task oriented.”

— Johan Blomkvist

Take, for example, the prototyping of the in-store experience of a retail store. To prepare, you might need to create a first sketch of the intended customer journey, consider your roles, practice the key scenes, set up the stage, and create a handful of key props (like an app prototype, some mock-up advertising posters, or a new checkout desk made of foamcore). You then use the setup to test the resulting experience (e.g., the checkout process). By using research methods like observation and interviews with the participants of your prototyping sessions you can collect a lot of data and capture and generate valuable insights.

It is important to understand that prototyping is not just about creating a prototype. 34 Rather, the creation of prototypes is only the starting point, which allows us to focus on using and testing prototypes and learning from them. 35 As Michael Schrage (author of the book Serious Play) says, “the value of prototypes resides less in the models themselves than in the interactions they invite.” 36 In this sense, prototyping indeed is research into future situations.

Data synthesis and analysis

Running prototyping sessions generates a lot of data, insights, and new ideas about the future service. So, as a next step you need to synthesize and analyze that prototyping data (sensemaking). As prototyping can be interpreted as research into future service situations, the synthesis and analysis process in prototyping is technically the same as the synthesis and analysis process that was covered in Chapter 5, Research. 38

Visualizing prototyping data

There are many ways to present your prototyping data, and once again what makes sense depends on your aim. Luckily, all the ways to capture research data in service design are also applicable for prototyping data. They include: 39

→ Research wall

→ Personas

→ (Customer) journey maps

→ Stakeholder maps

→ Key insights

→ Jobs to be done

→ User stories

→ Reports

Additionally, since you are now essentially working in solution space, there are two more tools that are especially useful:

→ Idea wall/portfolio: To get a quick overview of new concepts and ideas to be prioritized and lined up for prototyping and testing

→ The prototypes themselves: To make the future service experience tangible, and replace tedious verbal documentation

Again, it is important to consider the target audience for your visualization: Do you need something rather formal and self-explanatory so your outcomes can be used in different departments or organizations? Or are your outcomes only needed for your internal team? Any prototyping outcome that you need to communicate beyond your own team needs more polish.

Methods

Read more on methods and tools in our free online resources at:

![]() www.tisdd.com

www.tisdd.com

Prototyping Methods

This section provides concise descriptions of a selection of methods which allow you to prototype a broad range of services or products, whether physical or digital. As service design needs to provide a common language and support co-creation between different disciplines, we have chosen prototyping methods that do not require specialist skills. While this might sound limiting at first, this selection of methods allows you to push almost any concept to the point where you can make a safe decision on which experts you actually need to involve for which aspects of the project.

Many more methods exist and should be included in the planning and execution of your prototyping activities, but many of those require you to invite specialists from the respective field of expertise, like change managers, product designers, or software developers.

The prototyping methods selected for this book are structured in five categories:

→ Prototyping methods for service processes and experiences: Investigative rehearsal, subtext, desktop walkthrough

→ Prototyping methods for physical objects and environments: Cardboard prototyping

→ Prototyping methods for digital artifacts and software: Rehearsing digital services, paper prototyping, wireframing

→ Prototyping methods for ecosystems and business value: Service advertisement, desktop system mapping, Business Model Canvas

→ General methods: Mood boards, sketching, Wizard of Oz approaches 40

There are many variations of and names for each prototyping method, and the boundaries between the chosen categories might be rather fluid. Often, a specific prototyping method can also be adapted to answer different prototyping questions. Reflect on your chosen scope (including which elements of the service need to be prototyped), fidelity, and target context and choose the methods for your prototyping activities accordingly. As a rule of thumb, you might want to consider including at least a few methods to account for method triangulation. 41

Prototyping Service Processes and Experiences Investigative rehearsal

Investigative rehearsal is a theatrical method to deeply understand and explore behaviors and processes through iterative rehearsal sessions. 42

Based on forum theater, it is a structured, full-body way to clarify the emotional side of an experience and reveal many practicalities around physical space, language, and tone of voice. 43

Preparation: Choose and quickly prepare a (key) scene as a starting point, e.g. from research or from a future-state journey map, and create essential props and a stage.

Use: Play through the initial scene, repeating and commenting until there is a deeper understanding on a physical and motivational level. Only then, change the scene. Review the effect of each change and explore alternatives. Iterate. Always keep a list of bugs, insights, and ideas.

Research techniques: Use-it-yourself (autoethnography), participant observation, co-creative workshops

Expected output: Research data (specifically a list of bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos

Prototyping Service Processes and Experiences Subtext

Subtext is a theatrical method that can reveal deeper motivations and needs by focusing on unspoken thoughts in a rehearsal session. 44

We can think of subtext as the unspoken thoughts of a character – it is what we mean, but don’t say. Bringing subtext into a rehearsal session can reveal deeper motivations, help us understand needs, and illuminate new opportunities to create value.

Preparation: In an investigative rehearsal, identify a key scene. Now, hold the scene at one key statement by a customer or employee.

Use: Ask, “What would be the subtext of that statement?” Continue with, “What would be the subtext of that subtext?” and repeat. As you go deeper, ask how the service could respond at each level.

Research techniques: Use-it-yourself (autoethnography), participant observation, co-creative workshops

Expected output: Research data (specifically documentation of the subtext chains, new insights, and ideas), raw video footage and photos

A team “stress testing” the returns procedure of a retail service using investigative rehearsal. Two team members simulate the encounter, while others are ready to step in with alternatives to the process, setting, systems, or behavior.

Simply moving figures around on a map and acting out the dialogues allows you to quickly simulate a service experience.

Subtext: another actor speaks out loud the unspoken thoughts of one character as part of a rolling rehearsal scene – subtext is what we mean, but usually don’t say.

A visual sketch of a multilevel subtext chain.

Prototyping Service Processes and Experiences Desktop walkthrough

Desktop walkthroughs can be seen as interactive mini-theater plays that simulate end-to-end customer experiences. 45

Using maps, figurines, and small-scale models of the service environment, you test and explore common scenarios and alternatives of a service process or experience.

Preparation: Create an overview map for all relevant locations. Pick a figurine for each key stakeholder in your service and create essential props using paper, cardboard, modeling clay, etc. Decide on a story as a starting point.

Use: Run through the story using the maps as the stage and the figurines as actors. Act out all dialogues and interactions with other actors, devices, etc. After each runthrough, reflect on what you would like to change or try. Always keep a list of bugs, insights, and ideas. Then iterate.

Research techniques: Participant observation, interviews, co-creative workshops

Expected output: Research data (specifically documentation of the simulated variants, new insights, and ideas), raw video footage and photos

Early cardboard prototypes are cheap and easy to make. This has one of the lowest entry barriers of any of the prototyping methods.

After each step the team reflects on what worked, what didn’t work, and what they would like to change or try next. Keep it brief. Then move on.

After creating hand-sketched versions, a user can easily test the interface by “clicking.” An operator simulates the changes by replacing or adding parts of the interface.

Prototyping Physical Objects and Environments Cardboard prototyping

Cardboard prototyping refers to prototyping 3D mock-ups of almost any physical object or environment out of cheap paper and cardboard. 46

The prototypes – for example, the interior of a shop or a ticket machine – can be small scale or actual size. To explore the role the objects play in the context of the future service, cardboard prototyping is often used together with walkthrough approaches.

Preparation: Use simple materials to build the objects. Split your team into users, operators, and observers and give them some time to prepare.

Use: As the user starts to use the object (i.e., handling it, pressing buttons, etc.), the operators manually simulate the reaction of the object. Observe and keep a list of bugs, insights, and ideas. After each testing session reflect on what you would like to change or try. Then iterate.

Research techniques: Use-it-yourself, participant observation, interviews, co-creative workshops

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, documentation of the tested variants

Prototyping Digital Artifacts and Software Rehearsing digital services

Rehearsing digital services is a variant of investigative rehearsal that helps to prototype digital interfaces as if they were human conversations or interactions. 47

Within an investigative rehearsal, your app or web page is replaced by a human actor. This method can be used even before creating any wireframes or paper prototypes.

Preparation: Choose a starting point, e.g. based on user stories from research, and prepare props and a space. Then, quickly familiarize yourselves with the chosen story.

Use: Run through the story and have a human play the app or web page. Don’t think digital be a full human being, but one with superhuman access to knowledge and media, like a knowledgeable butler or “genie in a bottle.” For example, a landing page can be simulated by a concierge asking, “What are you looking for?” then evolving the conversation naturally. Afterwards, consider how to digitalize the experience.

Research techniques: Use-it-yourself, participant observation, co-creative workshops

Expected output: Research data (specifically a list of bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, updated wireframes or paper prototypes

Prototyping Digital Artifacts and Software Paper prototyping

In paper prototyping, the screens of a digital interface are hand sketched on paper and presented to a user to quickly test interfaces. 48

Users can now use the interface by “clicking” with their finger indicating what they want to do. A researcher simulates the operation of the computer simply by replacing the screen page or by adding “pop-ups” on smaller pieces of paper.

Preparation: Create hand-sketched versions of all key elements (e.g., pages, dialog boxes, and actual key content). Split your team to take on the roles of users, (computer) operators, and observers and give them time to prepare.

Use: As the user starts to use the interface, the operators simulate all changes in the interface by replacing or adding parts. Keep a list of bugs, insights, and ideas. After each testing session reflect on what worked, what didn’t work, what you would like to change. Revise your prototype and iterate.

Research techniques: Use-it-yourself, participant observation

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, documentation of the tested variants

Prototyping Digital Artifacts and Software Interactive click modeling

Interactive click modeling is a popular lo-fi method to create a first working digital prototype.

Special prototyping apps allow you to take photos of your hand-drawn sketches and link them together so you can test them on the actual device you are developing for.

Preparation: Hand-sketch all the different screens of the interface on paper, take photos of the sketches, and import them into the prototyping app. In the app you can now define click-areas that link between sketches, effectively creating a working interface.

Use: Ask a user to complete some tasks using the click-model and observe how she reacts to the interface. If you want to use the prototype for communication you can also film the use of the click-model for further reference.

Research techniques: Use-it-yourself, participant observation

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, documentation of the tested variants

Prototyping Digital Artifacts and Software Wireframing

Wireframing uses nongraphical schematics of digital interfaces and their structure to show how they fit together and create alignment within the design team. 49

Most of the elements are more hinted at than explicit, which makes wireframes fast to create, requiring less specialized skills. Wireframes are often used to align the different disciplines within a design team and to map out user journeys or act as the starting point for paper prototypes or interactive click-models.

Preparation: Rough versions of the different screens of the interface are sketched on paper, on whiteboards, or in special wireframing apps. Leave out color, specific fonts, and aesthetics as much as possible. Use placeholder content.

Use: The wireframes are put up on a wall and discussed with the team or a selected audience. Annotations are added to capture the behaviors of the marked interface elements and details about the content or context in which the system might be used.

Research techniques: Co-creative workshops, interviews, concept tests

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, documentation of updated wireframes and annotations

Special prototyping apps allow almost anyone (even without prior knowledge) to create interactive click-models of your interface. They can be shown to potential users for testing or storytelling to gather valuable feedback.

Wireframes help the design team to understand and explore how the different parts of software work together. They connect the conceptual structure, functions, or information architecture to the visual design.

Service advertisement posters are a fast and engaging way to quickly explore, clarify, and test your value proposition.

Prototyping Ecosystems and Business Value Service advertisement

Service advertisements are prototype advertisements that allow us to (re)focus on the core value proposition and test the desirability and perceived value of a new offering.

Like simple advertisement posters, they use concise slogans, engaging visuals, and text to sell the new offering. Later, service advertisements can be created as online ads, web landing pages, or TV or video advertisements (including in-depth documentary-style variants).

Preparation: Do a brief brainstorming on ideas for emotional and factual content for the poster. What do you want to communicate in the ad? What could be suitable emotional hooks or narratives? What are the facts? Sketch out a couple of advertisements on big pieces of paper.

Use: Show your advertisements to people who do not yet know your project and collect their feedback. Keep a list of bugs, insights, and ideas. Discuss what worked or what didn’t work, and what you would like to change. Revise your prototype and iterate.

Research techniques: Participant observation, interviews, co-design

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, quotes from the test audience

Business Origami first looks at the system taking a holistic approach. Like with many other service design tools, the critical deliverable is not the model itself but the experience of modeling the service system in the team.

Using the Business Model Canvas, you can quickly analyze existing business models and prototype new ones.

Mood boards are collages of existing media to communicate an intended design direction.

Prototyping Ecosystems and Business Value Desktop system mapping (a.k.a. Business Origami)

Desktop system mapping is an approach which helps us to understand complex value networks using simple paper cutouts representing key people, locations, channels, and touchpoints. 50

The cut-outs can be quickly placed, moved, and reconfigured again on a table or horizontal whiteboard. Relationships and value exchanges are visualized by grouping or drawing connections between different elements.

Preparation: Create, cut out, fold, and label the key elements of the service system using the paper templates.

Use: Create a draft of the service system by placing key elements to create a map. Reflect on relationships, value exchanges, (inter)actions, or basic material/money/information flows. Add those as arrows and consider grouping elements. Start to simulate the service system over time. Always keep a list of bugs, insights, and ideas. Then, revise your prototype and iterate.

Research techniques: Participant observation, co-design

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), raw video footage and photos, documentation of the ecosystem

Prototyping Ecosystems and Business Value Business Model Canvas

The Business Model Canvas is a high-level approach to co-create and visualize the key components of a business model that allows you to iteratively test and refine various options. 51

Considered a strategic management tool, it is intended to be used in an iterative design process.

Preparation: Prepare the Business Model Canvas template. It helps if you have personas, stakeholder maps, customer journeys, and prototypes at hand as well.

Use: Fill in the upper seven boxes first. If available, use information from other service design tools to fill in information from previous work. Then fill in the lower two boxes, identifying cost drivers and potential revenue streams. Add numbers and estimate costs and revenues. Prototype and test whether your business model is sustainable. Then start creating alternative business models and test potential options. Compare different models and iterate; combine and refine them. 52

Research techniques: Co-creative workshops, interviews

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), photos

General Method Mood boards

Mood boards are collages that help to visualize and communicate intended design direction.

Using a mix of text, sketches, visualizations, photos, videos, or any other media, they transport current or future experiences, style, or contexts.

Preparation: Start to collect inspiration and raw material (often photos or video footage) from magazines, stock photo libraries or your own media library, or quickly create new material yourself. Organize that material and set up a first collage. Iterate until you are happy. Your mood board can be a physical wall, or it can be an online media board, a more practical solution if you are working with video or interactive media.

Use: Present your mood boards either to each other within the design team or to an external audience to receive feedback and ignite discussions. During these presentation sessions, you can work on existing boards by adding annotations or adding, reshuffling, or removing media or even create completely new boards from a pool of data.

Research techniques: Studio interviews, focus groups, concept tests/discussions

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), photos, collages

General Methods Sketching

Sketching refers to methods of visualization or representation of design ideas that support fast and flexible exploration. 53

Sketches – low-fidelity visualizations of an idea – are flexible, quick, and inexpensive. Their explorative nature often makes them the first step in explorative prototyping.

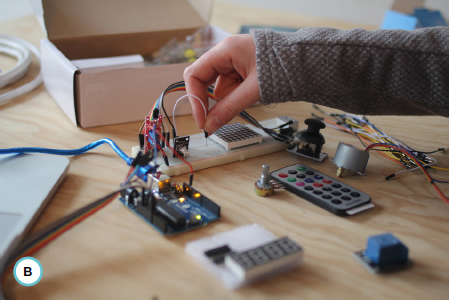

Preparation: Sketches are usually created fast using only pen and paper. However, you can create sketches with almost anything as long as they are quick to produce, inexpensive, and support exploration – e.g., sketching in software, 54 hardware, 55 or with our bodies (bodystorming).

Use: Present sketches to others to receive feedback and ignite discussion. During these sessions, you can directly work on existing sketches (e.g., by adding annotations or changing them on the spot) or easily add new ones with the changes already included.

Research techniques: Studio interviews, focus groups, concept tests/discussions

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), photos, video footage

General Methods Wizard of Oz approaches

Faking it using invisible puppeteers. 56

Wizard of Oz techniques manually create the responses from people, devices, apps, or the context/environment through invisible operators (“wizards”) behind the scenes. The users are led to believe that they are dealing with an actual working prototype.

Preparation: Think of the operator (“wizard”) as an invisible puppeteer for those objects and service elements. Prepare all relevant parts of the service or systems and rig them to allow the “wizards” to create realistic responses on the spot.

Use: A user is given specific tasks to use the prototype. The operator simulates the operation of backstage processes, devices, or the environment by operating behind the scenes and manipulating the objects and environment. Use this approach to explore and evaluate core functionality and value.

Research techniques: Participant/non-participant observation, contextual interviews

Expected output: Research data (specifically bugs, insights, and new ideas), photos, video footage, observations and interview transcripts

Sketches using pen and paper provide a quick and low-fidelity visualization of an initial idea or concept.

Open source prototyping platforms like Arduino allow you to sketch in hardware, creating first working prototypes of interactive devices.

With the right prototyping platform, sketching in code lets you explore working prototypes early.

In Wizard of Oz techniques, the responses from people, devices, apps, or the context/environment are manually created by invisible operators (“wizards”) behind the scenes.

Bodystorming, or “sketching with our bodies,” is a very efficient lo-fi way to sketch (inter)actions using re-enactment.

This methods section only provides a concise selection of prototyping methods, specifically chosen to not require specialist skills. This allows you to have a conversation within a broader team about where the project should be heading. It also allows you to make safer decisions about what kind of skills and expertise will be needed when moving toward implementation; e.g., when you dive deeper into change management, software development, product development/management, architecture, or other more specialist disciplines. You can now safely invite the relevant stakeholders with their expert methods.

Those specialists bring in specialized tools to tackle specific challenges quickly and efficiently, including but certainly not limited to:

→ Software prototyping tools and frameworks

→ CAD (computer aided design) and 3D printing

→ Change management toolsets and structures

→ VR (virtual reality) applications for architecture and experience prototyping

→ Fablab (fabrication laboratory) environments or makerspaces with access to tools that allow you to prototype almost any physical object

When you choose suitable methods for your project, carefully assess how quickly they will allow you to build and test the prototype. Your choice might also depend on the skills of your team and the tools they have access to. 57

It can be useful to put together your own tailored prototyping pipeline or even create your own prototyping lab.

Where can you run a quick service simulation? Are you allowed to prototype in context? How fast do you get access to fabrication equipment, and are you able or even allowed to use it on your own? Do you have instant access to a user community for a quick user research, or do you first have to go through a long purchase process? Where can you experiment with fresh ideas and grow them before you need to apply for funding?

Your own prototyping lab can start small and be quite informal. With iteration, it might develop into something useful enough to become an official internal institution. 58

But remember, whatever you set up, always keep it accessible to your whole organization and stay fast. 59

Figure 7-7. Virtual reality environments and content can be highly engaging. Unfortunately, authoring VR content often still requires specialist skills – but as tools evolve this might change rapidly, making it one of the most exciting technologies not only for prototyping but also for documenting and revisiting field research data.

Cases

The following six cases provide examples of how prototyping is applied in practice: how to enable effective co-creation through prototyping minimum viable solutions and contextual mock-ups (“Case: Enabling Effective Co-Creation Through Prototyping Minimum Viable Solutions and Contextual Mock-Ups”); how to use prototyping and co-creation to create ownership and close collaboration between the designers, project group, and staff (“Case: Using Prototyping and Co-Creation to Create Ownership and Close Collaboration”); how to enable staff and stakeholders to prototype for continuous evolution (“Case: Enabling Staff and Stakeholders to Prototype for Continuous Evolution”); how to create minimum lovable products, living prototypes, and high-fidelity sketches in code (“Case: Minimum Lovable Products, Living Prototypes, and High-Fidelity Sketching In Code”); how to use role-plays and simulations in large-scale 1:1 prototypes (“Case: Using Role-Plays and Simulations in Large-Scale 1:1 Prototypes”); and how to use multifaceted prototyping to create and iterate business and service models (“Case: Using Multifaceted Prototyping to Create and Iterate Business and Service Models”).

-

- Innovation on the shop floor: How to demonstrate the value of design thinking to a manufacturing organization

— Thomas Abrell, Innovation Manager, Airbus

— Dr. Markus Durstewitz, Senior Innovation Manager, Airbus

7.3.2 Case: Using prototyping and co-creation to create ownership and close collaboration

- Reducing the waiting time for breast cancer patients

— Marie Hartmann, Design Director, Designit Oslo

— Kaja Misvær Kistorp, Lead Service Designer, Designit Oslo

— Emilie Strømmen Olsen, Senior Service Designer, Designit Oslo

7.3.3 Case: Enabling staff and stakeholders to prototype for continuous evolution

- Infinite prototyping

— Johan Dovelius, Head of Service Design, Doberman

— Henrik Karlsson, Creative Director, Doberman

7.3.4 Case: Minimum lovable products, living prototypes, and high-fidelity sketching in code

- ATO Partner Space case study

— Andy Polaine, Design Director, Fjord Evolution APAC

— Eduardo Kranz, Service Design Lead, Fjord

— Chirryl-Lee Ryan, Global Design & Innovation Principal, Fjord Evolution

7.3.5 Case: Using role-plays and simulations in large-scale 1:1 prototypes

- Prototyping at scale: Redesigning Lufthansa’s business class experience

— Barbara Franz, Senior Lead Design and Research, IDEO

7.3.6 Case: Using multifaceted prototyping to create and iterate business and service models

- Multifaceted prototype evolution over time

— Klara Lindner, Head of Customer Experience, Mobisol

Case: Enabling Effective Co-Creation Through Prototyping Minimum Viable Solutions and Contextual Mock-Ups

Innovation on the shop floor: How to demonstrate the value of design thinking to a manufacturing organization

AUTHORS

Thomas Abrell Innovation Manager, Airbus

Dr. Markus Durstewitz Senior Innovation Manager, Airbus

Crafting a design thinking strategy and proving it in reality

Design thinking at Airbus emerged organically from different departments – workshops were conducted, training offered, and projects following human-centered approaches established, all labeled under the term design thinking. However, besides a core group of departments that formed a deep understanding of the power design thinking can have in product and service innovation, the majority of employees of Airbus have different understandings of design and design thinking, if they are acquainted with the concept at all. In July 2015, we crafted a strategy to infuse design thinking as part of the DNA of Airbus. One step on the ladder toward a broader understanding of design thinking was to engage in a grand challenge: we wanted to show, in an investment project of strategic importance, the potential of design thinking. Airbus is currently extending its production capacity of its successful Single Aisle Family, A319, A320, and A321. To enable this ramp-up, Airbus has created an additional final assembly line in Hamburg. Our value proposition in this project was to co-innovate with the workers at the shop floor.

The project started in September 2015 and focused on problem framing and need finding from the workers’ perspective. To ensure visibility and to reach the right level of awareness, it was important that design thinking was placed prominently in the project structure as one dedicated work stream. Being placed at this level gave us enough influence to push for creating real impact by achieving an end-to-end implementation.

“With design thinking, we are following a balanced approach that emphasizes early user engagement. The purpose is to make sure that we address the real needs and focus on doing the right things, which finally will make the difference to succeed with innovation in delivering added value to customers and users by going beyond the obvious.”

— Dr. Markus Durstewitz

Prototyping plays a prominent role in the design process as a tool to make assumptions tangible and to involve users. We applied prototyping for gaining user insights, and for ensuring employee engagement and management buy-in. Our prototypes were often quite simple, rough mock-ups such as cardboard prototypes or clickable user interfaces. In general, these are good enough to test functionalities and to continuously involve users in the evolution of the concepts. In addition, we used the prototypes to better understand goals and the rationale behind requirements from different departments. Here, interdisciplinary and cross-functional collaboration was essential to reach consensus between all stakeholders.

“Fast iterations in prototyping minimum viable solutions are a key asset for gathering user insights, for reducing the time to product, and for accelerating the innovation process.”

— Dr. Markus Durstewitz

By having tangible prototypes and the possibility to interact with and alter them, we were able to gain deep insights, tapping into the tacit knowledge of the different stakeholders. We used the prototypes to test early and fail fast and cheap, in order to iterate to a solution that would ultimately be valuable to the end users and approved by all stakeholders. The simple prototypes helped us to perform early user tests and to reach a good level of maturity and alignment before making bigger investments.

From need finding to prototyping: Finding opportunities beyond the obvious and prototyping in design thinking

We started out with user research to understand how the production environment is perceived from a worker’s point of view. We shadowed key people, going through their workdays with them, and we interviewed workers on the shop floor and other relevant stakeholders such as production support and manufacturing engineers. The need-finding stage lasted three months, in which time we can to understand the final assembly line from the workers’ point of view. We distilled our findings into four opportunity areas where design can make a change.

“Although it is tempting to shortcut in the early phase, crucial for the success was to conduct deep need finding prior to prototyping. Only through going into the field, observing and shadowing users, was it possible to look beyond the obvious and to ensure we are doing the right things.”

— Thomas Abrell

After need finding, we selected two of the four opportunity areas to prototype in a timebox of eight weeks, from kickoff until the final prototypes were delivered. To master this tight timeline we built a team of internal and external experts with diverse skills, from industrial design and rapid prototyping to user research to coding.

We addressed two challenges in an iterative way, utilizing prototypes as a tool to co-create, to communicate, and to iterate: information system interfaces on the shop floor and material delivery.

In building the team, we relied on experienced service designers from Airbus to manage the overall design process, project and stakeholder management. For the information system side of the project, we chose an external partner with specialists in industrial design, design thinking, and user experience design. It was also important for us to bring in perspectives from a non-aerospace domain, bringing in diverse skillsets and design expertise.

Prototype in the final assembly line.

Sketch of the future system.

Information system interface feedback session.

Scale models as tools in the process.

Prototyping: Making things tangible on the shop floor

The project was set up in such a way that two teams worked in parallel, one focusing on the physical prototype, the other on the information interaction prototype. It was important to co-locate the teams in a creative space: we used an aircraft fuselage and built a workshop around it, so that our team had the possibility to continually build things.

Our experiment was to see how digital and physical prototyping could work in parallel, involving all stakeholders. Workers were involved continuously. In addition, we scheduled three co-creation workshops to engage a wider group of stakeholders, a demo day, and an intermediate management presentation. We used a build-measure-learn cycle, but instead of measuring, we relied on qualitative evaluations and direct feedback from the users. The co-creation workshops were used to iterate the prototypes, and we moved from lo-fi mock-ups to functional usability mock-ups.

“It was an interesting experiment to run physical prototyping in parallel to digital prototyping. Ultimately, we designed a service for the workers, involving digital and physical touchpoints. Our aim was clearly to improve the work experience for our employees.”

— Thomas Abrell

With the information system interfaces, we complemented our need finding by researching what information workers really need – and want to use – to perform their work, and which devices would be suitable for interacting with the information. We therefore enriched our findings from the need-finding phase, and observed and interviewed the workers specifically with respect to the information they need. We mapped the necessary information and prototyped it in rough concepts, showing screens on different devices such as tablets, smartwatches, smartphones, and large touchscreen displays.

In the first co-creation workshop, we got user feedback on the devices and the functions. We distilled the most important insights before going into the next prototype iteration, until a user interface was generated and a device concept was determined. Finally, we took the prototypes into one existing final assembly line, and let the users interact with them, simulating their very own workflow with the new prototypes in their current day-to-day working environment. These insights helped us to further iterate and refine them.

The material delivery units (MDUs) were addressed the same way. First, we went to the shop floor to see how material delivery works in practice – complementing the view we had from need finding, the planning documents, and internal logistics. Then, we conceptualized three material delivery units and built 1:5 scale models – in practice, three material trolleys for the same set of material, but with different conceptual considerations behind them – which were iterated in co-creation workshops.

One week later, we had the first 1:1 full-scale mock-up, which was brought to the final assembly line for feedback at the assembly station itself. With this feedback, and feedback gathered in the co-creation workshops, we built two more iterations of the full-scale mock-up. We added “smart” functionalities (connectivity) to the prototype, simulating how it would interact with its environment and the parts inside. The second prototype iteration got additional usability features such as a bumper and boxes for tools to make it more usable and more useful for the worker.

In the last co-creation workshop, we simulated a scenario incorporating both prototypes, the information system interface and the material delivery unit. Our project team simulated the situation together with the users, gathering feedback about the overall workflow, since material delivery and the information system interface are interrelated in their respective workflow.

At the editorial deadline of this book, we are doing a proof of concept of the material delivery unit, and integrating the information system interface into a larger project at Airbus changing the way our manufacturing environment is set up and operations are performed. The learnings of the project are being used to propose a holistic design thinking approach for Airbus.

Learnings

Crucial for success were not only user engagement and user acceptance, but also the involvement of the Workers’ Council as a key stakeholder. This entity, entitled to represent the workforce, can amplify a project’s results in positive or negative terms. Only through continuous deep involvement of the council did we create a sense of ownership, involving them as a strategic partner for employee engagement implementing user-centered solutions.

“It’s important to have a good balance between internal and external project team members. Only with a small internal core team is it possible to maintain continuity during the project, while external team members bring in specific expertise.”

— Thomas Abrell

For the future, we will need a small internal core team with a wide array of skills to anchor the approach and leverage the expertise until implementation. In practice, it will be an interdisciplinary team consisting of aircraft manufacturing domain experts from Airbus, designers, method experts, and specialists for end-to-end support of the innovation project. We believe that collaboration with external partners from the design community (e.g., with freelancers and design agencies) will be necessary to keep up a high level of momentum and creativity.

“People are at the heart of our company. Let’s complement the diversity of our employees and introduce a new way of working in cross-functional teams to deliver outstanding results. Let’s team up for innovation! This may include all actors along the value chain, suppliers, customers, and users.”

— Dr. Markus Durstewitz

Now, the next step is to go further in our endeavor to make design thinking part of the DNA of Airbus, by creating a specific design center to coordinate and steer the activities and to give creatives a home within the organization. In this organization-to-be, we want to educate service designers inside Airbus, and build up a strong network spanning Airbus.

Key Takeaways

01 Deep need finding is necessary to ensure that you are “doing the right things.” If this phase is bypassed, you run the risk of merely incrementally improving existing solutions instead of innovating.

02 Prototyping is a powerful tool for demonstrating to stakeholders the power of a design team. Designers are fast at making assumptions visible and tangible. This craft helps to make tacit knowledge of stakeholders explicit, and to get buy-in for design thinking as an innovation approach.

03 A combination of external and internal team members is crucial, but the right balance needs to be found. A team of experts is needed to be fast, and it should be complemented by a cross-functional team from the organization to make innovation happen.

04 A new way of working for users leads to a strong commitment to finding solutions. However, these solutions might be in conflict with traditional metrics in the company, and the speed of working might alienate parts of the organization. Although benefits such as increased usability can be related to KPIs such as increased performance, organizations also need to acknowledge “soft” experience-related factors as benefit.

05 It is crucial to create the right environment for design teams to work in. Having not only an inspiring workspace but also access to prototyping facilities is clearly necessary. Also, a shared location is mandatory for success, as much of the information otherwise gets lost in transmission.

Case: Using Prototyping and Co-Creation to Create Ownership and Close Collaboration

Reducing the waiting time for breast cancer patients

AUTHORS

Marie Hartmann Design Director, Designit Oslo

Kaja Misvær Kistorp Lead Service Designer, Designit Oslo

Emilie Strømmen Olsen Senior Service Designer, Designit Oslo

By reducing the waiting time for breast cancer patients from (up to) three months to seven days, Oslo University Hospital used service design methods to improve the lives of women facing a difficult period in their lives.

Women with a heightened risk of developing breast cancer typically faced a delay of up to three months before receiving an examination and diagnosis at the Oslo University Hospital, the largest hospital in Scandinavia. Supported by the Norwegian Design Council’s Design-Driven Innovation Program (DIP), Designit worked together with a project team at the hospital to reduce waiting time and improve the overall patient experience. The collaborative, visual, and iterative process enabled the hospital staff to work more closely together and envision a new system.

Service thinking and co-creation