Chapter 12. Embedding Service Design in Organizations

How to sustainably integrate service design in organizational structures and processes.

Expert comments by:

Eric Reiss | Fernando Yepez | Hazel White | Klara Lindner | Maik Medzich | Mike Press | Ole Schilling | Sarah Drummond | Simon Clatworthy

-

12.5.1 Case: Including service design in nationwide high school curricula

12.5.2 Case: Introducing service design in a governmental organization

12.5.3 Case: Increasing national service design awareness and expertise

12.5.4 Case: Integrating service design in a multinational organization

12.5.5 Case: Creating a customer-centric culture through service design

12.5.6 Case: Building up service design knowledge across projects

This chapter also includes

Getting Started

How to introduce service design in an organization

Just acquiring service design capabilities is not enough to sustainably introduce service design in an organization. That process usually includes a cultural and organizational transformation that cannot be implemented within a few months. 1 It requires the alignment of the whole organizational system, including organizational structures, processes, practices, routines, and values. It is a change process in itself, and needs to be carefully designed and managed.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“One of the infuriating things about service design that I have experienced, is that people need to do it to understand it. So, the more you can get people to do service design, the better the understanding and uptake.”

— Simon Clatworthy

It’s much easier to introduce service design if the organizational transformation builds on a supportive corporate culture. Signs of this are, for example, customer centricity, cross-silo thinking and doing, or an iterative way of working, such as early prototyping. While there’s a lot of knowledge on how to change organizational structures, processes, and sometimes even culture, there’s no silver bullet that works for all organizations.

Both a top-down approach and a bottom-up approach to introducing service design have potential pitfalls. While a pure bottom-up approach often lacks management buy-in and so also budget and approval, top-down approaches often lack support from employees as they feel that they are being forced to deal with “just another buzzword.” The successful introduction of service design requires commitment on various levels: from the top and the bottom, but particularly also from someone in the middle who initiates the first project and connects top and bottom needs, expectations, and perspectives.

Small projects, sometimes also called “island projects” or “stealth projects,” that fly under the radar of an organization are a good way to get started with service design.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Start with an annoying in-house challenge! To get the ball rolling and [get] service design into your organization, take your own staff as first users and collaborate on an issue that has been bugging everyone for a while. At Mobisol, we used the development of an internal communication guide to create a shared language and our own way of applying service design.”

— Klara Lindner

The involvement of influential middle managers can make the introduction of service design easier and more successful. They might be “influential” in terms of formal decision-making powers or because of informal social ties within an organization. 2 However, service design can only become a continuous success if top management approve the introduction and support it with enough resources like budget, time, and people, as well as some personal involvement. Some practitioners refer to this as the middle-top-bottom approach.

Start with small projects

Small projects are the ideal starting point as they can be detached from existing structures and processes, in particular from requirements to integrate with complex IT systems or business initiatives. Many things might cause your first project to drift away from the initial plan, and you need to limit both your expectations and those of your team – and in some organizations also the expectations of your superiors. Plan a mix of well-defined projects – ones where you are quite sure of success, and others where there is a chance they will go wrong.

It might help if you clarify up front what kind of results can – or cannot – be expected from a specific service design project, to make sure that everybody is aligned on the expected results. This will later help pinpoint unexpected positive or negative results. Luckily, service design projects usually provide a few unexpected quick wins that might help you to promote the approach within your organization and help you to get management buy-in.

This could also be a chance to bring “skeletons” out of the closet – projects that might be important from a business perspective but where nobody knows how to tackle the problem, or where someone has tried and failed before.

Try to choose first projects that include open and collaborative stakeholders to avoid wasting time and energy with unmotivated team members. Use these smaller projects to adapt the service design process and language to your organizational structures, processes, and culture. Focusing on just one project risks putting too much pressure on a team, and if this one project goes wrong, you might have “burned” the term service design (or whatever you call what you’re doing) in the organization forever.

Indeed, it often helps if at first you give the service design approach a name which does not stand out in your organization. 3 A rather traditional project title helps you avoid too much early attention and gives you time to work out how to adapt service design to your organization, to fail in a safe space, to analyze what could be done better next time, and to understand where exactly in the process something went wrong. Perhaps you can even reuse the work done before the failure, and just try again from there – with the crucial lessons learned. 4

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Always be on the look-out for a champion or two within the organization. These are people with influence who can champion your case further up in the organization. Find them, and feed them regularly!”

— Simon Clatworthy

Secure management buy-in

If needed, find someone from management to sponsor your initial projects. It is often said that “budget is how organizations express their love,” but management buy-in is not only about financial backing, but also about political support within your organization. Often just a brief introduction from higher management will give a design team the credibility that you might need for your first projects.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“To get senior buy-in, nothing beats showing them films of a user failing to use the service that they manage or have commissioned.”

— Sarah Drummond

It helps a lot if your sponsors have decent service design knowledge. Offer opportunities to experience service design through a hands-on approach, perhaps by involving higher management during research, running a pressure-cooker format like a mini-workshop or a short jam 5 with them, offering internal and external workshops and talks, or inviting visits from other companies who have introduced a more “design centric” approach within their business. Although top management don’t need to be service design experts, they should be aware of the general process and potential benefits and pitfalls.

Try to speak a common language, understand their current goals and challenges, and remember that their time is often limited. Sometimes, “translating” project-specific details into the overall business strategy of a company helps to find a common ground; for example, by showing how a service design project relates to business and growth opportunities.

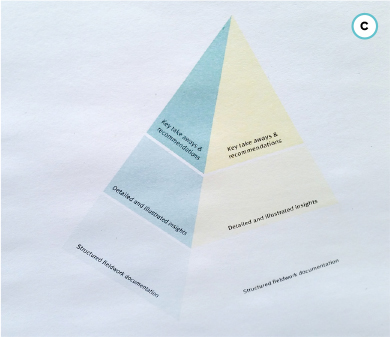

Up front, define a clear aim for the project with all team members and management. For small and well-defined projects, it is often even possible to agree on specific key performance indicators for a project. 6 Try to measure these before and after the project to understand and prove its impact. Document your project throughout the entire process using photos, videos, quotes from participants, and artifacts like personas or journey maps, as well as measuring potential impacts of your project. Remember to keep doing this as you approach the end of a project, when other things become very important. This is not only crucial to showcase your project and way of working to others, but also to celebrate the successes with your team.

Raise awareness

When you have found “your” way of doing service design 7 through a series of small “stealth” projects and have developed management buy-in, you can start raising awareness within your organization. Good documentation of previous projects can help you do this organically. Project documentation should include the state of an experience before and after the project (if possible with a measurable impact) as well as the design process and how the team worked together. 8 Video summaries or short reports with plenty of photos usually work quite well, shared through a newsletter, an internal website, or a blog.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“A quick way to gain management support early on is to know in advance some of management’s agenda. What do they really care about and what are their goals? Choosing projects that address those cares, goals, and concerns align the outcomes of a service design project to management reality and increases management buy-in.”

— Fernando Yepez

Another approach is to casually showcase high-fidelity journey or system maps that address a specific experience before and after a project – perhaps by hanging them in your office and even in hallways or coffee areas. 9 It helps if these maps are self-explanatory. Also, you can provide some general information on the project and particularly on the process the team went through.

Project participants from various departments and backgrounds can team up to educate others through demonstrations. The goal is not to up-skill non-designers to designers, but to create champions of the process throughout an organization. Explaining a project and the design process to others often brings better understanding for those who have to present, and stories from your own organization are better for promoting service design than cases from other companies. Make clear that service design works in your organization, in your structures, in your culture.

You can also use classic internal communication channels to celebrate achievements and showcase successes, such as posting an article in an employee newspaper, or asking someone from senior management to recap a project during a corporate event. It might make sense to explain the philosophy behind a project and what you hope to achieve with this. Also offer further reading, a listing of events, or contact details of someone within the organization so employees can learn more.

Both internal participants and management sponsors are often great advocates for service design in an organization and could act as a catalyst for further projects. You might raise enough interest that employees ask you for more information, and you can identify motivated people for your next projects. 10

Build up competence

As a next step, strive to build up and spread competence. Identify motivated colleagues from different departments and organize internal talks, workshops, masterclasses, jams, conference visits, and the like. These colleagues are often the best ambassadors within an organization and can help to diffuse service design knowledge organically by word of mouth. You can help them by offering them information they can share, such as an internal service design website or brochures showcasing projects, process, methods, and tools. Often they will convince new people who might show up to your events.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Capacity building is vital to scaling up. But this must go hand in hand with leadership and a strong sense of community. Our research shows that these three factors are indivisible in taking service design to the next level.”

— Hazel White

Sometimes, you will need to define a common language and standards for your organization. Often people think they are speaking the same language, but in fact have in fact understood service design differently. Inconsistent terminology makes collaboration inefficient and conflictual. 11 The aim should be to build up competence across different departments and to establish a network of like-minded people. Establishing a community of practice like this generates a safe space in which you can openly share lessons learned, success stories, and failures.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Staff’s lack of time and empowerment is the biggest barrier to taking projects forward. Senior management need to give this, and it must be part of the project budget.”

— Sarah Drummond

Give this community an easy way of sharing, such as a shared chat room or community page, but also establish regular face-to-face meetings to learn with and from one another. Invite your project sponsors and management and include them in your community.

The more management understand the process, tools, and methods, the more they’ll realize that design needs a specific type of leadership. Micromanagement and uneducated decisions by superiors can demotivate a design team and ultimately kill innovation.

Give room to try

Three of the most quoted barriers to organizational change are employee resistance to change, management behavior that does not support change, and insufficient human and financial resources. Service design projects are rarely successful if employees have to run them on top of their daily work. This is no different to any other project.

“You get what you pay for” is a saying in many agencies, and the same is true for projects that are run internally. Empower employees with time, support, budget, and sufficient responsibility and decision-making power so they can really do a service design project. Ideally, a service design project is a separate activity outside of any other daily activity. Think, for example, of temporarily occupying a space outside the regular workspace, such as a dedicated creative space or design thinking center. 12 This ensures that your service design initiative will not get lost in day-to-day business and helps to bridge the spatial separation of departments.

Scaling Up

How to set up a service design team in an organization

Not everyone needs to be a service design expert, although a basic level of design knowledge for everyone – or at least an understanding of what design is for – has proved valuable in some great companies. Depending on the size of the organization, there’s often a core service design team that keeps an overview of the end-to-end experience and coordinates all service design projects. 13 Each individual project, however, has its own extended project team built around the competencies needed for the specific project.

Service design projects are a great opportunity to give members of different departments a common focus and objective outside their normal work routines.

The core service design team

The members of the core team are usually experts on service design management, processes, tools, and methods, as well as facilitation. The role of the core team is to manage or support projects and perhaps facilitate them through workshops and activities. They do not necessarily need to be experts on specific products, processes, or departments. 14 Sometimes, it even helps if they are unfamiliar with organizational structures and processes or do not know how customers use certain offerings. They are often hired from outside the company to bring in know-how or are employees that are trained in service design and facilitation. In a small, private grocery market or a printing house business, this core team might have just one expert. In a government department or a multinational telco corporation, it might have hundreds. Members of this core team can be internal employees or external consultants; perhaps a service design agency that commits to a long-term relationship. External members are often better able to openly point out the inconvenient truths. Often, a mix of internal and external members is most promising.

The extended project teams

While the core team is rather small and focused on the service design process, most projects are also supported by extended project teams: larger groups of people with specific competencies related to the subject matter. These extended project teams should be as cross-functional and multidisciplinary as possible. The size of an extended project team can vary over time; it often even changes from workshop to workshop.

One aim of service design projects within larger organizations is to facilitate the organizational transformation toward a more customer-centric culture. Service design can help break down entrenched silos by connecting people from various departments.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Organizations are complex systems. As such, it is hard for a system to change itself. An outside view seems to be a catalyst for aiding change to happen. Therefore, part of building a community of practice should include the knowledge and experiences of other outside subject matter experts and practitioners.”

— Fernando Yepez

Members of the extended project teams are often people that normally work apart from one another and sometimes even compete over budgets or KPIs. Working together in a project might help them to establish personal connections and ultimately get on the same page. 15

“Where does the project brief come from?” and “Who needs to implement this?” are two questions you should always ask yourself when you start a project in an organization. You might, for example, learn about similar earlier projects and find people who were previously involved. They might be able to assist you in selecting your team members and managing stakeholders. As the size and composition of the extended project team can vary over time and depending on the project needs, the core service design team need to determine who to include and when. 16

Extended teams should include people that are directly affected by the problem the organization is willing to solve – affected staff as well as users and/or customers. In the long run, across several projects, the people who were part of an extended team form a loose community of practice. With every project they pick up more and more, until some of them might eventually switch into your core service design team.

Choose a name that fits your culture

Often, it doesn’t make sense to reinvent the wheel and raise expectations or even suspicions by using fancy names such as “Service Design Task Force” or “Design Thinking Squad.” The core service design team should be named in a way which fits the corporate culture and strategy. Build on whatever exists already and only use a new name if you do this consciously.

A new department for service design might be useful if you want to push the approach internally and if this reflects your corporate strategy. However, this requires a corporate strategy that includes a commitment on service design; long-term management buy-in; internal service design competence; a shared language of service design; and a working process that is adapted to corporate structures, processes, and culture. If not, you might raise expectations that you probably cannot deliver with your first round of projects.

Name individual project teams according to the subject of their project, such as “call center improvement team” or “work group for online shopping experience.” These unsuspicious names do not reflect the underlying method and help to reduce prejudices and barriers. Mentioning the subject matter also helps to generate a common understanding and identity. Members of the service design core team will usually not name service design as the underlying approach. The technical language of service design should remain within the core team, while extended service design project teams use the shared language of the subject matter.

Connect with the wider service design community

Working in cross-functional design teams is extremely rewarding but also demanding. The service design teams need to facilitate a process of organizational change, motivate stakeholders to look at things from different angles and distances, engage and inspire internal and external stakeholders, and often also break with or at least challenge an existing corporate culture. They will need to find ways to engage and inspire themselves at the same time. This can be triggered and nourished by connecting with the wider local and international service design community. Organizing and participating in community events, such as service design drinks, service design thinks, conferences, workshops, or jams, 17 connects the core team formally and informally with experts outside of the organization who can become crucial in future projects.

Sponsoring service design and innovation events like these increases employer branding and might attract further service design talents to your organization.

If you don’t have a local service design community, you could be the one to start it. Look for like-minded people through social media and invite them for a first casual meeting. You’ll find interested people in similar communities, like UX design, or at startup events. On a global scale, you’ll find an active service design community in all common social media channels; just search for the hashtag or keyword #servicedesign. Use any opportunity you find to share your stories and learn from others. The wider service design community is delightfully open and happy to share success stories as well as lessons learned from projects that went wrong. 18

Establishing Proficiency

How to lead organizations that integrate service design

Organizations of all sizes and sectors are affected by an ongoing digital transformation, with the increasing threat that their existing business models might be challenged or disrupted. This is one of many reasons why organizations are focusing more on customer centricity, innovation, and design in general. However, organizational structures, processes, and leadership approaches often still reflect a product-centric approach with many different silos, hierarchical structures, and processes. Their innovation process is often driven more by technology, by products, by engineering and learned behaviors, and less by human-centered design, by ethnographic research, and by co-creation with customers and employees. Many recent articles in business journals reflect the increasing awareness of service design, 22 but leadership 23 often struggles with such an open and fast approach, where you need more trust and less control.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“In designing better services, we are also designing better work. Think of it as a new form of industrial democracy.”

— Mike Press

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“One particular side effect turned out to be the most relevant reason for applying customer-centric methodologies: project owners learned better arguments to fight back against ifs and buts throughout the decision process.”

— Maik Medzich

Service design is not only a process and a toolset, but can be a management approach to innovation and business in general. It is an approach that is human-centered, that is based on value co-creation for multiple actors, that negotiates meanings and perspectives, that contributes to social innovation, and that proposes evidence-based solutions.

An organization that has integrated service design requires a certain kind of leadership. The following list presents some key suggestions for the leadership of such organizations.

Understand the design process

As a leader in a service design context, you should understand and value qualitative research and prototyping. You should appreciate the concept of a “sh!tty first draft,” 24 the importance of early stakeholder involvement, and the powerful process of early user feedback and iterative improvement. If you don’t agree with this, you’ll have a hard time working with a team doing service design.

→ Tip: Learn by doing Participate in service design workshops to learn some basic tools and methods and to experience the process yourself. You can’t learn to play football out of a book. Service design is just the same.

Lead through co-creation

Service design uses educated decisions based on research and prototyping. In the end, it is customers who decide if they want to use your product or not. The earlier you include them in your decision-making process, the more promising the outcome of your project is. To educate your decisions you need to understand customers and frontline employees.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Remember, no one within a client company ever has much empathy for outside service consultants. We are often viewed as expensive parasites. That means be prepared to give others credit for your work. If you can further their careers, the better the chances are that you will be hired again – and ultimately, you will achieve buy-in for more service design initiatives that really make a difference.”

— Eric Reiss

→ Tip: Lead by example. Be part of research and prototyping and experience this firsthand. Go out to see yourself how customers react to a prototype instead of listening to presentations by your team.

Eat your own dog food

You should personally use the products offered by your organization. This is often one of the first steps in service design to help management understand a certain issue beyond mere reports and statistics. 25

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“To create buy-in and make sure the approach is sustainable, develop new service assessment processes which require senior stakeholders to use the service. This makes sure managers are taking decisions from the customer perspective.”

— Sarah Drummond

→ Tip: Regularly become a customer of your own organization. Use products your company offers – just as any other customers do. Do this at least once a month, quarter, or year. Some organizations incorporate this approach into their culture, and management meet afterward to share their experiences and discuss potential consequences. Some companies do the same with frontline work experience.

Practice empathy

It’s important for service design leadership to understand the needs of people (employees, customers, stakeholders) and recognize critical situations (customer problems, team conflicts). If you understand your team, you will be able to give them the support they need. You’ll establish mutual trust and empower your design team to achieve more.

→ Tip: Dedicate time to train empathy. Almost everyone has the ability to empathize with other people, but often we don’t make use of it. Try to dedicate some time for this regularly: become aware of people you do not normally deal with in your organization, perhaps starting with the extended service design team. Be curious about their work routines, their lives, and their thoughts in general. Just ask them, show serious interest, and focus on listening – you want to learn something from them, not the other way around.

Look beyond quantitative statistics and metrics

You may have heard – or even repeated – the saying, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” This is an outdated myth from an era when management was restricted to quantitative tools. Customer experience is more than metrics. Numbers can help you identify that you have a problem and maybe where the problem is, but can’t tell you why people like or hate something, or what their aspirations are.

→ Tip: Focus on human experiences. Look beyond mere numbers and use qualitative and mixed-method approaches to understand experiences more holistically, including the human and the business aspects. Use statistics and metrics to find problems or track developments over time, but use qualitative research to understand why people like or dislike something, to understand what they are trying to be, and to inspire your team.

Reduce fear of change and failure

Employees at all hierarchical levels often fear change because it happens too frequently, is initiated “top-down,” and often has a negative impact on their own experience. Co-creation can lower this fear if you involve your employees in this process, embrace a culture of failure, 26 and are open to feedback and change yourself.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“If an insecure manager interprets suggestions as personal criticism, junior employees may fear that suggesting change could actually get them fired. If you truly want suggestions, you have to create a safe environment. You also have to provide timely feedback. All too often I hear, ‘We’ve told management about this problem for years, but they never listen.’”

— Eric Reiss

→ Tip: Ask for prototypes instead of presentations. Show that you use a design approach yourself. Support prototyping – for example, by relying less on shiny presentations and more on using sh!tty first drafts yourself. Encourage your employees to prototype their ideas together with customers and fellow employees. Allow them to test ideas and iteratively improve concepts with a clear and transparent innovation process and decision criteria.

Use customer-centric KPIs

Instead of only using KPIs that reflect the performance of single departments (silos) of an organization, add cross-silo KPIs that are based on customer experience. This can help departments to think beyond their boundaries. In order to impact these KPIs, departments need to work together and co-create with customers and employees. Reward those departments that take an active lead in impacting such customer-centric KPIs.

→ Tip: Connect silos through KPIs. Try out cross-silo KPIs that are based on customer events – for example, ones that can be described within the job-to-be-done (JTBD) framework. These KPIs might focus on customer satisfaction analysis regarding a specific JTBD, combining that with complaints, churn, and so on. Offer co-creative service design projects to the relevant departments so they can work together to impact these KPIs.

Disrupt your own business

Some organizations ask their employees to constantly challenge their own company, their own products. Waiting for other companies to find completely new ways of solving a customer’s problem with a new, disruptive solution might ultimately put your company at risk.

→ Tip: Empower employees to find problems and suggest projects. Invite employees across your entire organization to look for new business opportunities that might put your organization at risk. Establish a system for your employees to submit insights or ideas, to select the most promising, and to explore them outside of their daily routines together with your core design team.

Make design tangible

Instead of talking about what design is and how this can help an organization, follow a “doing, not talking” approach and constantly make design visible and tangible everywhere. Make your innovation and design process more transparent by exhibiting research data and insights, personas and journey maps, prototypes and workshop documentation.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“A good measure of how the organization is absorbing service design is to listen for terminology changes within the organization, and the way terms are used. Touchpoints and customer journey quickly get absorbed, but you really feel you have cracked it when people in a project team start discussing what kind of experience an employee or customer will have at stages of a journey.”

— Simon Clatworthy

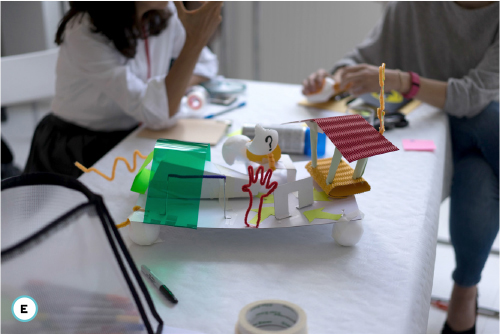

Prototyping, for example, is a great activity to understand the feasibility and sustainability of a new idea, as well as a good way to test and understand the organization’s willingness to change. Making design tangible lowers the barrier for others to participate in co-creative processes.

→ Tip: Showcase the impact of design in your organization. Exhibit journey maps showing the impact of service design projects in your own company. For example, show a journey map of before and after a project, and highlight the differences. Give some information on the process, tools, and methods, and add a contact from whom interested employees can learn more. This helps you to identify motivated people.

Bring service design into the organizational DNA

If you aim to bring service design sustainably into your organizational DNA, you might decide to stop talking about service design. Instead, you and your team will work naturally with service design tools and methods, follow the basic principles, and work in an iterative, collaborative, and human-centered way without thinking about this as “service design.” Thus, it stops being a special approach carried out by a dedicated group of people, and becomes everyday for everyone.

In the long run, when service design is part of your organizational DNA, you don’t need a dedicated service design team.

→ Tip: Do service design without talking about it. Show your own passion for this way of working without mentioning service design, but simply by using the tools, methods, and principles in various situations – for example, by using prototypes instead of presentations, or by co-creating meeting documentation, perhaps even in a visual way through graphic recording, instead of sending around written meeting minutes that no one reads anyway.

Think about which decision rights your employees have; if your organizational structure allows them to work collaboratively, self-responsibly, and in an interdisciplinary way; if they know how their performance is assessed; and which objectives or incentives motivate them to follow this way of working.

Design Sprints

How to set up service design as an ongoing activity in an organization

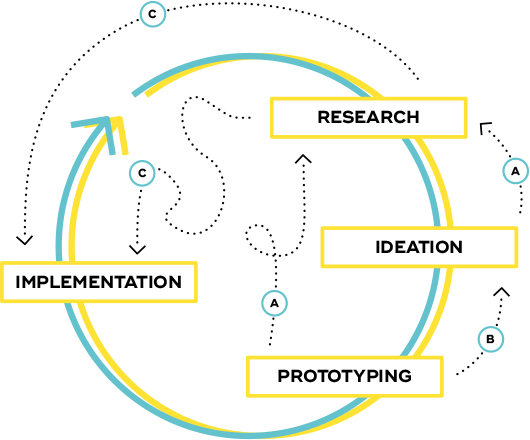

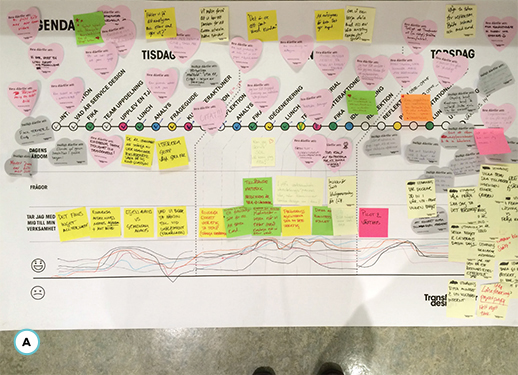

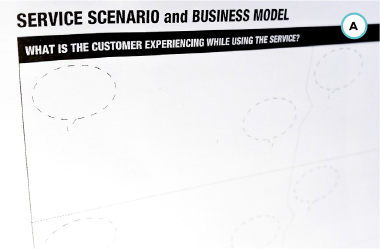

One way to implement or introduce service design in organizations is as a sequence of design sprints. 27 Each sprint can be understood as a single service design project. 28 In larger projects, a sprint refers to one iteration within the project – for example, focusing on a specific step or stage of an experience. Once a project is implemented (or discarded), the next sprint starts with an evaluation of the overall customer or employee experience. Thus, the first step of any new sprint also includes an evaluation of the impact of the prior sprint.

Working with sprints can be effective because it gives teams a framework to work in. A design sprint provides a rough process structure with a specific deadline. The team need to deliver something at the end of each design sprint and receive feedback. However, within a sprint, the design team can adapt the process and iterate as needed. This also helps to manage the iterative service design process as you can work in a predictable structure. Often, a core service design team manages the sprints and builds the extended project team based on the specific topic of each sprint. The extended project team may vary within a sprint. 29

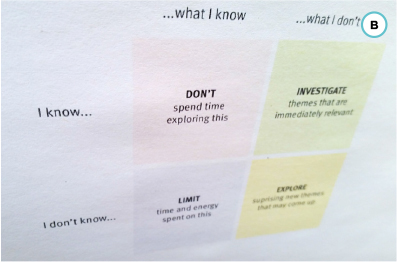

Research 30

Use qualitative and quantitative research to understand and review the existing customer and/or employee experience. Often previous sprints or a general roadmap guides the team to focus on a specific research topic. Research also includes evaluating the impact of previous sprints on the experience and business success. A design team then defines the next design challenge(s).

Typically, they use visualizations of their research data, such as system or journey maps to identify critical steps in the customer experience, often building on existing visualizations and adapting them based on their research. Journey maps and other visualizations should become living documents that are challenged in every new design sprint.

Research should also focus on the internal process of previous sprints and question team dynamics, problems, implementation challenges, and so on to iteratively improve the sprint process.

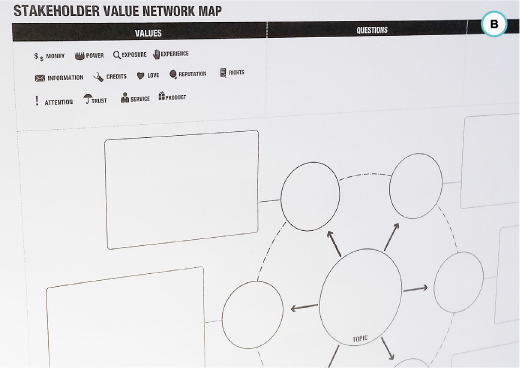

Figure 12-1. SERVICE DESIGN SPRINTS: IN THEORY

An archetypal structure of a service design sprint often looks like this.

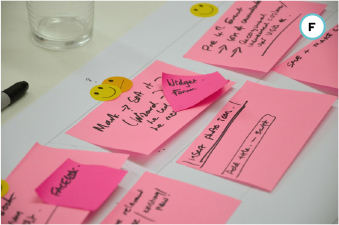

Ideation 31

Based on the defined design challenge(s), a process of idea generation (diverge) and idea selection (converge) starts. If necessary, some more focused design research can be done to scrutinize the critical steps you identify. Ideation should take into account earlier ideas that have been “parked” (e.g., in an idea portfolio or on an idea wall). If organizational hurdles must be overcome to convince decision makers before prototyping, early ideas can be progressed into initial example concepts.

Prototyping 32

Selected ideas are iteratively prototyped from low-fidelity concepts to high-fidelity prototypes and tested in context as early as possible. Prototyping can be focused on technical feasibility and look-and-feel, but here the main aim should be to test if an idea actually provides value to the customer, user, and/or employee. Prototyping and testing the value of an idea often provides a team with the arguments they will need to gain buy-in for further development and implementation. At any point during this stage, concepts can be discarded, iterated further, or “looped back” for additional research and ideation sessions.

Figure 12-2. SERVICE DESIGN SPRINTS: IN PRACTICE

In reality, the design process within a sprint is iterative in itself. For example:

When you realize that you’re missing research data, you can always go back and do more research.

When you realize that an idea or concept doesn’t work during prototyping, you go back to ideation or the last working prototype.

When research brings up very obvious issues that need to be (or could be) fixed immediately, fix them.

Implementation 33

Once an idea has been successfully tested in context, and approved by the design team and (if needed) by superiors, it will be implemented and rolled out. Larger organizations often follow a step-wise implementation process from first local pilots to regional test rollouts to global implementation.

Sprints in organizations

The duration of service design sprints often depends on many factors. As a rule of thumb, small companies, such as startups, often work with sprints of 1–4 weeks based on their agile and lean structure. In particular, software startups can integrate a model like this seamlessly within their existing agile development workflows to define requirements as epics or user stories. Small- and medium-sized companies often use slightly longer sprint durations of 4–12 weeks, and some larger companies and governmental organizations even work in sprints of 3–6 months. Organizations use various names for sprints 34 depending on their individual context.

Some organizational structures and cultures tend to make it easy to work in sprints, while others make it much harder. Practice shows that a corporate entrepreneurship philosophy and intrapreneurship behaviors are helpful for design sprints. This type of managerial philosophy usually fosters employee empowerment and learning opportunities, and it promotes incentive systems, exemption phases, and serendipitous activities such as cross-silo networking, open innovation activities, and loose structures. For instance, some companies organize separated dedicated spaces to support experimentation with entrepreneurial ideas (e.g., internal incubators, accelerator programs, internal ventures). Employees get a chance to pitch their ideas (or better, their functioning prototypes) to a jury of external experts and internal decision makers. If accepted, they can continue the exploration with a small team of colleagues, supported by coaching and sometimes even funding to develop a minimum viable product (MVP). 35 If this succeeds, some programs even offer venture capital to start a spin-off outside of the existing organization. Through such initiatives, ideas can leapfrog the paralyzing structures of large organizations at the same speed as a startup.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“At this stage, you need management buy-in. If you define new criteria and deliverables within existing processes this will lead to governance questions: Who is responsible for developing deliverables? Who is checking the quality? Who is paying for the additional activities? Key for us was that top management started to ask: Where are the deliverables like personas and journey maps? Without them, I cannot decide.”

— Ole Schilling

Many organizations integrate design sprints within their existing innovation process – for example, a stage-gate process. In cases like this, it is important to review the existing decision criteria with a critical eye. It’s hard to get better results if you change the innovation process but keep the same decision-making system. A system that stops projects before ideas can be explored further through an iterative design process is not helpful.

Cases

The following seven case studies provide examples of how service design can be embedded in organizations of various levels: how to include service design in the nationwide high school curricula of Austria (“Case: Including Service Design in Nationwide High School Curricula”), how to introduce service design in a governmental organization (“Case: Introducing Service Design in a Governmental Organization”), how to increase the national awareness of and expertise on service design (“Case: Increasing National Service Design Awareness and Expertise”), how to integrate service design in a multinational organization (“Case: Integrating Service Design in a Multinational Organization”), how to create a customer-centric culture through service design (“Case: Creating a Customer-Centric Culture Through Service Design”), and how to build up service design knowledge across projects in a large organization (“Case: Building Up Service Design Knowledge Across Projects”).

12.5.1 Case: Including service design in nationwide high school curricula

- Service design in secondary schools

- — Helga Mayr, Teacher and Course Coordinator, Pedagogical University Tyrol

12.5.2 Case: Introducing service design in a governmental organization

- Unleashing creativity in an exhausted governmental organization

- — Daniel Ewerman, Founder and CEO, Transformator

- — Sophie Andersson, Senior Service Designer, Transformator

- — Anton Breman, Senior Service Designer, Transformator

12.5.3 Case: Increasing national service design awareness and expertise

- The emergence of service design in Thailand

- — Waritthi Teeraprasert, Senior Design and Creative Business Development Officer, Thailand Creative & Design Center

12.5.4 Case: Integrating service design in a multinational organization

- Redesigning Deutsche Telekom

- — Ole Schilling, Senior Design Manager, Deutsche Telekom

- — Philipp Thesen, Chief Designer

- – Lead Telekom Design, Deutsche Telekom

12.5.5 Case: Creating a customer-centric culture through service design

- Toward a sustainable customer-centric organization

- — Tim Schuurman, Co-Founder, DesignThinkers Group and DesignThinkers Academy

- — Vladimir Tsaklev, Continuous Improvement Leader, Coca-Cola Hellenic BSO

12.5.6 Case: Building up service design knowledge across projects

- Working with moving targets

- — Geke van Dijk, Strategy Director, STBY

- — Katie Tzanidou, UX Research Manager, Google

Case: Including Service Design in Nationwide High School Curricula

Service design in secondary schools

AUTHOR

Helga Mayr Teacher and Course Coordinator, Pedagogical University Tyrol

Austria leads the way in disseminating service design by being the first country worldwide that has implemented service design in the national curriculum for all secondary schools with a business focus. 36

Service design as a school subject

Since 2016, service design has been part of the Austrian national curriculum for secondary schools, integrated into a subject called “Business and Service Management.” 37 There are approximately 90 secondary schools with a business focus in Austria and each school can individually define the scope of this subject, from 2 to 12 teaching hours per week. The work on the new curriculum started in 2011 with the objective of creating a subject addressing “business organization and implementation in reality.” In 2012, a nationwide working group was established to support the introduction of the new subject. Four years later, in 2016, the new curriculum came into effect by decree. Business and Service Management is now taught nationwide.

By integrating service design in the curriculum, a space for “doing” as a promoter for sustainable learning has been created, with a strong focus on a multidisciplinary approach and applicability to business practice in the context of entrepreneurship education.

Meeting different goals

As graduates will predominantly find jobs in the relatively unspecific “service industry,” they should be able to understand the nature of services as a whole. This includes knowing how services can be designed – including research, ideation, prototyping, and implementation – as well as identifying various stakeholders and considering backstage processes.

The subject in which service design is integrated was introduced in order to offer students the opportunity to link and practically apply what they had learned in different subjects.

Along with helping students acquire an entrepreneurial attitude, teaching service design will contribute to reaching the educational objectives of “active citizenship” and “employability.” Integrating a seminal (trendsetting) innovation approach makes students fit for actively “designing” their (and our) future.

Implementation

The big challenge was – and still is to a certain degree – the question of how to anchor service design in the schools as it is still a relatively young discipline. Two years before the new secondary school curriculum was launched, the “concept” of service design was presented to a selected number of potential multiplicators, such as teachers and school principals. The audience were interested, but initially uncertain about how service design could be brought into the classroom.

Thanks to the internet, we realized that Marc Stickdorn was living just around the corner in Innsbruck, Austria. We contacted him to set up some further presentations and workshops to help us understand what service design actually is, how it can be beneficial for high school students, and how it could be taught in school. Then, we asked him and his colleague Markus Hormess to set up nationwide teacher training in service design.

Nationwide teacher training

We set up these nationwide teacher training sessions as courses offered by the Pedagogical University Tyrol in Innsbruck exclusively to teachers that are responsible for this new school subject. There are two consecutive three-day courses: a “basic” course and a follow-up “advanced” course.

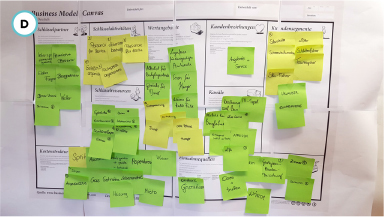

The three-day basic course includes basic service design tools, such as personas, journey maps, stakeholder maps, and prototypes, as well as the Business Model Canvas. It also includes some of the main service design activities: research, ideation, and prototyping. A big part of this first course is about the mindset and the iterative design process, as most of the teachers do not have a design background. The whole course is set up as a train-the-teacher course. As all participants are professional pedagogues, the course content focuses on service design in practice and gives the participants enough time to review and discuss how these tools and methods can be taught in school.

The three-day follow-up course adopts a more open “bar camp” or “unconference” approach. 38 Topics range from case studies, to exchanging first experiences, to trying out lessons and prototyping classroom materials.

“Our course topic was ‘Street Food’ and we prototyped the entire situation with a rented truck so that we could even produce and test our kitchen prototypes in the actual situational context.”

— Marianne Liszt, Teacher at HBLA Oberwart/Burgenland

Gaining experience

In the winter semester 2016/2017, the third nationwide basic course and the second follow-up teacher training took place. More than 100 teachers in Austria have been through the training already and are passing on their knowledge to their students and colleagues, sometimes doing team teaching together with colleagues from other subjects.

Actually, implementing service design as a subject in secondary schools is a service design process on its own. Both teachers and students start with “sh!tty first drafts” and improve them iteratively: the teachers their lessons, the students the services they work on in their classes. In order to constantly improve this process, teachers can constantly exchange experiences and share teaching material through an online forum shared with the growing community of service design teachers in Austria. In addition, we have received requests from teachers to establish an annual meeting fostering a living community of practice of service design teachers in Austria.

Desktop walkthroughs are often a good start for prototyping and can help to visually connect customer experiences with frontstage and backstage employee processes.

Assumption-based personas are easy and fun to do for students, but are only useful when they are backed with research data afterward.

Creating first assumption-based customer journey maps to introduce journey mapping and emotional journeys in class.

The Business Model Canvas is a great tool to connect service design with other business and economic subjects in school, like management, financing, or accounting.

Using various warm-ups with students in class changes the relationship with the teacher and breaks out of routines that students are used to in classrooms.

Students at the school HBLA Oberwart used service design methods to create a food truck service on campus. 39

Prospects

Given the fact that service design is still in its infancy in schools, it will – without a doubt – stay exciting. We will academically monitor and evaluate the further process of implementing service design in secondary education in Austria during the upcoming years. One of our research questions is how students benefit from early service design education in their professional and maybe even in their private lives. Also, we hope with growing experience within our community to be able to offer profound guidance on how to effectively and successfully implement service design in secondary school curricula. Nevertheless, we can already see some initial results that we would like to share.

The individual degree of implementation at each school seems to depend on several influencing factors. One of these factors could be how service design is introduced to schools on a national level. In Austria, this is done through a mixture of a top-down approach (by including service design in the national curriculum of secondary education) and a bottom-up approach (by training teachers and establishing a community of practice), which seems promising so far. Another route to success might be to start with small projects and learn iteratively, tolerating – or even welcoming – errors as a source of knowledge for further improvement. Moreover, it is certainly helpful to raise awareness within the school (amongst all related stakeholders, such as teachers, students, parents, partners, and so on) and also between schools, by communicating about service design activities, exchanging experiences with colleagues, and staying open-minded about student involvement.

Indeed, one of the key drivers might be an open mindset and the willingness to share experiences and to learn from others. Finally, school principals are key stakeholders that also need some basic service design knowledge to understand the design process, methods, and tools. This knowledge will allow them to understand school projects related to service design, and how students and schools can benefit from these.

“Service design is also an attitude, an open, sensitive observation and perception of events that very often initiates a change process.”

— Bernadette Zangerl, Teacher at HLW Landeck/Tirol

Key Takeaways

01 Start with small projects, learn from errors and successes, and then iterate.

02 Be sure to keep an open mind and be willing to share experiences in order to learn from others.

03 Educate key stakeholders on service design to help them better understand and support your project.

Case: Introducing Service Design in a Governmental Organization

Unleashing creativity in an exhausted governmental organization

AUTHOR

Daniel Ewerman Founder and CEO, Transformator

Sophie Andersson Senior Service Designer, Transformator

Anton Breman Senior Service Designer, Transformator

With decreasing citizen trust and employees pushed to the limit of their engagement, Arbetsförmedlingen (the Swedish Public Employment Service) needed to find a new way forward and create a cultural change. At the time, Arbetsförmedlingen had 13,000 employees, 320 offices, and 27 million customer contacts every year.

Prior to this project, a line of projects had been done to design customer-centered solutions. The link between negative customer experience and internal problems was mapped. A clear prioritization for the changes was developed. But instead of simply commanding the offices to “implement these solutions and make them work,” Arbetsförmedlingen took a brave turn and put frontline staff in charge of the change.

“The understanding of our trust problem had existed more or less for a long time, but the positive results as an effect of the understanding had been absent. We really had no choice other than to become more customer-centered in our approach, and that’s why we turned to service design and decided to let our employers and our customers be a part of the development.”

— Helena Engqvist, Former Director of Communications, Arbetsförmedlingen

“We didn’t try to convince everyone, we started with those who were curious and volunteers. Today nearly the whole organization wants to be a Greenhouse.”

— Pia Rydqvist, Customer Service Manager, Arbetsförmedlingen

Engaging employees

Offices were invited to participate, and seven with a range of conditions were chosen to become “Greenhouses.” The staff got to attend a three-day crash course in service design, testing methods, tools, and the approach. The offices were introduced to the service solutions and got to perform the final iterations on a local scale.

They adapted the solutions to their everyday conditions and prototyped, interviewed customers, generated ideas for adjustments, and made the final designs. A central support function was set up, with service designers from Transformator Design and headquarters staff to moderate the process and coach the offices. So far 24 offices have become Greenhouses.

“We thought maybe that solutions could be implemented without the employers having an understanding of the customers’ needs and why we needed to change. This was a mistake, but that’s the great part with this whole approach – it’s based on making mistakes, but making them early, admitting them, learning from them, and adjusting as you go.”

— Pia Rydqvist, Customer Service Manager, Arbetsförmedlingen

The result was a range of revised solutions that headquarters now knew would work well in large and small offices, in cities and in the countryside, and from the customers’ and the employees’ points of view. The changes were implemented with great buy-in from the front-line staff and created a sense of organizational ownership.

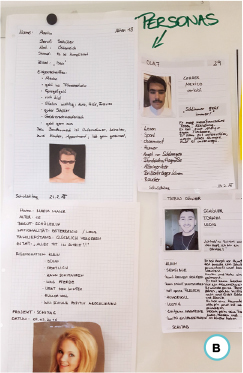

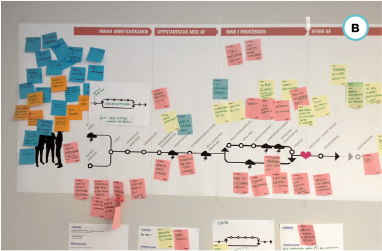

Employee journey mapping to learn and adapt service design principles internally.

Example of a customer journey made by the internal team being used as a tool for understanding and change management.

Greenhouses as a tool for the employees to use their customer expertise, zoom out, and create space for creativity in their daily operations. 40

The management structure for coaching the organization toward full ownership and a mandate in the transformation process. 41

When the first concept was implemented in 320 offices it resulted in a reduction in time (from 50 minutes to just 10) spent on practical registration in the first meeting, freeing time for focusing on the individual’s ambitions and needs. The decrease in citizen trust stopped, and employees say that the service design approach helped soften hierarchies and erase prestige, leading to drastically increased health and work satisfaction.

“Learning will take some extra time in the beginning, but we believe customer-driven development must be built in as a natural part of the everyday work.”

— Pia Rydqvist, Customer Service Manager, Arbetsförmedlingen

Effects on organization

Customer-driven development is now seen as an essential part of the organization’s future, and in June 2016 a permanent support function was implemented to establish the Greenhouse concept throughout the organization. So far 2,000 employees, including 400 managers, have been introduced to service design and the importance of a customer-centric approach, but the goal is to offer it to all employees. The support function will make sure that:

— Customer knowledge is shared and collected so that the development of services can be conducted in local offices.

— Future national development projects will be coordinated in Greenhouses.

— The Greenhouse framework continues to be relevant and contributes to creating better services, based on needs of the citizens.

“We can’t go back to the way we worked before. Once you’ve learned the tools and methods, and more importantly adapted the approach, you can’t keep [from] applying it to everything in your work”

— Anna Palmgren, Head of Arbetsförmedlingen, Växjö

Key Takeaways

01 Prepare a solid base of courage.

02 Filter it through simplicity.

03 Let it ripen through action learning.

04 Practice what you preach.

05 Make sure to use a baking tin of persistence.

06 Let it drip with reality.

07 Finalize it through organizational ownership.

Case: Increasing National Service Design Awareness and Expertise

The emergence of service design in Thailand

AUTHOR

Waritthi Teeraprasert (rAiN) Senior Design and Creative Business Development Officer, Thailand Creative & Design Center

Realizing the service economy’s importance in creating value and improving the quality of life for Thai people, and boosting the country’s competitiveness in the field of services, Thailand Creative & Design Center (TCDC) is the first Thai organization to introduce service design to Thailand, experimenting and applying it to various organizations in both the public and private sectors.

We initiated a Service Design Thailand program with the ambition to drive service design as a major part of improving existing services or boosting service innovation for businesses and public services in Thailand.

We first introduced service design in TCDC’s annual symposium, Creativities Unfold 2012, by inviting Birgit Mager, President of the Service Design Network and Professor of Service Design at the Köln International School of Design, to lecture on the value of service design. She presented ideas from countries such as Germany and Finland, which take a systematic and efficient public service development approach; this resulted in Thailand’s first service design workshop. Participants included design professors, TCDC, and public service organizations, namely the Thai Post Office, the State Railway of Thailand, and the Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning (OTP).

Workshops

The workshops created awareness among public service organizations of the role and importance of service design. Consequently, we have participated in two projects planning the future of Thailand’s public transportation system:

1 The Service Design Research for User Insights and Needs in High-Speed Trains (HST) Project, a co-creation project between TCDC, OTP, and Livework, resulted in the implementation of the design principles of space and services within the development of high-speed train stations. This project illustrated the importance of the design to the public sector, as the HST Service Design Principles were under the Terms of Reference of OTP, the organization that handled the Thailand HST feasibility study program.

2 The Hua Lamphong Train Station Improvement Study Project is a study of the unchanged, century-old Hua Lamphong train station. Our team applied service design, starting with field research, user studies, and moving on to a complete service design process. The result was physical improvements, including updates to the passenger waiting area and commercial area around the station, as well as a feasibility study of the new service design and the establishment of a new business model for Hua Lamphong Station in the future.

In 2014, we invited service design experts Marc Stickdorn, Markus Hormess, and Adam Lawrence to disseminate their knowledge more widely by hosting two types of service design workshops. First, a “Train the Trainers” program trained service design facilitators, who then acted as knowledge disseminators themselves, facilitating future service design workshops. Second, our guests facilitated co-creation workshops to initiate three projects in different service sectors: the healthcare sector with Bumrungrad International Hospital, the hospitality service industry with Thai Hotel Association, and the tourism sector with Designated Areas for Sustainable Tourism Administration (Public Organization). The concepts and prototypes derived from these workshops have been implemented in these organizations.

Additionally, we set out to involve the education sector in supporting and amplifying service design. This initiated cooperation among five universities. Choosing the topic of “Service Design for Public Transportation,” with a high-speed train as a service design development target, teachers and students from all five universities together learned the concepts and process of service design and created prototypes showcased in the “Service Design for Public Transportation” exhibition.

Training courses

We also created short-term service design training courses for the general public under the Bangkok Service Jam project, as well as hosting special service design training courses for 13 universities under the miniTCDC project, disseminating knowledge through workshop facilitation. The workshop results were service design prototypes in each local case.

After accumulating lessons, opportunities, problems, and obstacles from our service design program (which has mostly focused on the service sector in the past few years), in 2015, we challenged ourselves as well as the agricultural and manufacturing sectors with the question, “How can we transform Thai businesses from manufacturing and product-oriented companies to customer experience – and service-oriented companies using the service design approach?”

Large company adoption

We introduced the service design approach to two large-scale Thai companies – namely, STC Group, a leading company in the agricultural sector, and PTT Chemicals, a manufacturing company – and we were able to convince the executive boards of both companies of the importance and benefits of service design’s principles, processes, and tools. We also initiated co-creative service design projects based within these two organizations by gathering the companies’ staff and various stakeholders: we invited the production, product R&D, sales, and marketing departments, as well as top-level management, to join our service design workshops and training programs. We and our team facilitated the workshops, executed the whole service design process, and concluded with product and service prototypes.

This is a starting point in applying service design and the design thinking process. These companies may not have transformed themselves within a few years, but feedback from the companies is quite positive, as they have gained experience during these workshops and training programs. They have adopted new approaches which have given them a better understanding of their customers and the way their departments think and operate. They are creating prototypes and testing minimum viable products and services, comparing their prototypes with their existing business processes. The new approaches have led to changes in their manufacturing and in the organizations themselves.

Talking about the customer journey and touchpoints.

Making and testing a low-fidelity prototype.

A discussion on a customer journey during a service design workshop.

A multifaceted collection of insights helps guide our projects.

Creative district

To promote TCDC moving to Charoenkrung and to apply design thinking and service design on a larger scale, we and our partners initiated the “Co-Create Charoenkrung” project. The project’s aim was to revive and develop Charoenkrung district – once a significant economic and social area of Bangkok – to become a creative district of the future. The project, which ran from July 2015 to June 2016, was conducted using service design thinking and doing principles and processes, focusing on co-creation among experts on creative cities, architecture, and design, as well as key stakeholders in the district.

In co-designing the creative district, we invited designers and local people (who are not only users but participants) to express the problems and articulate the opportunities and needs of the community. This led to a concept of project development in various forms, steps, and processes: starting from design research, gaining insights, generating ideas, co-designing, making paper prototypes and 1:1 full-scale prototypes, and testing and evaluating with the local people in the real spaces. The ultimate goal of the project involves not only developing the creative district but also developing a “co-creation model” as well as the principles and processes of service design thinking and doing which can be applied to our beloved Thailand.

Our service design programs and schemes have just started; nonetheless, they have raised awareness among the public, business, and social sectors and provided essential outcomes. These include service prototypes for future investment and development. Our creation and dissemination of service design knowledge through workshop facilitation, together with project-based and co-creative schemes with other organizations and communities, have publicized and developed service design knowledge, as well as reinforcing the service design network and ecosystem that will create economic and social impacts in Thailand in the future.

As a result of these activities, we’ve seen major engagement with service design. From March 2013 through June 2016, 1,500 people attended our service design workshops. Additionally, our YouTube channel has logged more than 87,000 views. TCDC has encouraged 30 public and private organizations and 30 universities to participate in service design activities.

Key Takeaways

01 The simplicity of service design and its process: People are surrounded by services in almost every aspect of their lives. So, it is quite easy to educate, teach, train, and apply service design in either life or work.

02 Co-creation in multi disciplinary projects: Service design and the design thinking process can lead non-designers to understand design differently, as a method of solving problems and creating value. “Design” is not only for designers; it is the process of co-creation with people from various disciplines (whether they are experts or amateurs), blending experience and backgrounds and providing the appropriate solutions.

03 Facilitation of workshops: The best starting point for service design (for those people or organizations who are new to the approach) is to run through a service design workshop. This means that the intelligence and skills of the service design facilitator are the key to success. Even if they have great facilitation skills, good facilitators have to know or learn some specific content before they run workshops.

Case: Integrating Service Design in a Multinational Organization

Redesigning Deutsche Telekom

AUTHOR

Ole Schilling Senior Design Manager, Deutsche Telekom

Philipp Thesen Chief Designer – Lead Telekom Design, Deutsche Telekom

The challenge

Deutsche Telekom operates in 14 countries, serves 160+ million customers, and has an annual turnover of around 70 billion euros. As a formerly state-owned company, we are mainly driven by technology and infrastructure. Just over seven years ago, the design department was established to challenge every product and service while driving customer centricity in order to achieve a best-in-class customer experience: a daunting challenge for a tech giant that used to be run by the government.

Our goal

From the 2016 World Economic Forum in Davos to the boardrooms of billion-dollar corporations, design thinking is a widely embraced approach to creative problem solving. Thanks to the increasing importance of customer experience as a key differentiating factor in most businesses, the role of design is changing – from form-giving to strategy-giving. Design has adopted a strategic leadership role and, by doing so, caused a major hiccup for large corporations in which design has traditionally played a less prominent role. We had one goal: a best-in-class experience for our 160 million customers. And we knew that in order to accomplish that, we needed a sustainable mind shift across major parts of our organization. This is the story of how it happened.

“Over the past few years we have successfully worked on more than 200 products and services for Deutsche Telekom and managed to climb the design ladder from a focus on form to focus on processes, slowly working our way up to a focus on strategy.”

— Philipp Thesen, Chief Designer, Lead Telekom Design

From doing to thinking

We leveraged the potential of design by integrating design thinking into the fundamental processes throughout the company. There are only about 100 designers in our team, so we could never hope to keep up with the increasing need for design. That’s why we created tools and assets that would serve the organization while leveraging the potential of design and design thinking. We operationalized the processes and methods that we derived from our experience of design doing. Additionally, we analyzed existing design thinking methods while adopting approaches from various schools of thought, including from Stanford University and HPI.

Ultimately, we took external methods and hundreds of interviews and weighed them against our own internal expertise and experience in order to create a standardized set of methods and tools tailored for our organization.

This led to common ground, a clear understanding of responsibilities, and clean integration within the existing organizational structure. We created a selection of 17 methods, customized for our needs, along with detailed personas and practical tools and templates. It’s the standard toolset of our daily work and it helps us to collaborate in a way that is both efficient and customer oriented. The toolbox is continuously extended and updated. It’s available as a book and online within our corporate design tool, Brand & Design, a platform we created for our colleagues to distribute and leverage design.

“We aligned the design process and the integration of our methods and tools within the development process with our German and European colleagues that work on customer-facing products and services.”

— Ole Schilling, Senior Design Manager

We strongly believe that visibility is key and we actively communicate and showcase our customer-centered ideal. This is also why we launched a new format for interaction called Customer Lab. On a regular basis we invite real customers, selected on the basis of our personas, to challenge existing products and proposed product innovations. This approach is especially powerful because it generates valuable feedback and insights which we embrace by inviting our colleagues across the company to share this knowledge and drive the visibility of our topic. Inviting the management team so that they can experience customer feedback firsthand is a simple, yet extremely powerful tool. Live and direct – customer-centric design.

Educational framework

Although we invited our colleagues at an early stage to engage with us and discuss how to implement customer experience KPIs with existing processes, the reality is that within large corporations change happens in baby steps. So, we need to foster a culture in which the principles of design thinking are largely embraced within corporate culture and values. The logical next step was to create an educational framework.

Consistency leverages product experiences across products.

Getting all stakeholders on board as early as possible.

Testing and learning.

Speedport Neo – customer-centric design.

Prototyping early.

Sharing experiences and creating ambassadors.

Product experience is brand experience.

“Design Thinking Doing” – the custom- tailored handbook for customer-centric design at Deutsche Telekom.

Establishing design as a leadership discipline for digital transformation.

In order to drive real change we created a space and program dedicated to focusing on design thinking: the Telekom Design Academy, a place where we teach our methods and the use of our tools but also support our colleagues with real project facilitation. We realized that the demand for project facilitation and on-the-job design thinking training can be applied to specific topics. Demand far exceeded our expectations, which is why we had to start staffing our internal and external teams immediately.

Learnings

We come from a strong legacy of design doing. This entitles us to create and implement processes and tools for our colleagues that will drive change within our company. Integrating design into processes ultimately brings us one step closer to integrating design into the corporate strategy. For now it’s clear that we still have a long way to go to become a more design- and customer-oriented company, but we are well underway and design has taken a leadership position within the company.

Key Takeaways

01 Integrate stakeholders and users as early as possible in order to help design thinking become a common approach. Start with the stakeholders who are most open to collaboration.

02 Make the approach as tangible as possible so it’s clear how it works and what the benefits are. Create a clear target picture and work your way toward it. Don’t waste time with theoretical discussions.

03 Integrate new processes into the existing context and make them as visible as possible. Make sure that there is a top-down pull toward the necessary deliverables. Leadership involvement is, however, very beneficial along the way in order to lay the foundation.

04 Design thinking is far too important to be left only to designers. However, the experience designers gain from a strong design doing background makes them the perfect ambassadors for design thinking. Building a community of experts has been especially beneficial for our European rollout, in which learning from and building upon on each other’s experiences proved to be essential.

05 Don’t expect results to be immediate. Change needs time.

Case: Creating a Customer-Centric Culture Through Service Design

Toward a sustainable customer-centric organization

AUTHORS

Tim Schuurman Co-Founder, DesignThinkers Group and DesignThinkers Academy

Vladimir Tsaklev Continuous Improvement Leader, Coca-Cola Hellenic BSO

The Coca-Cola Hellenic Business Services Organization (BSO) is a fast-growing shared services center in Sofia, Bulgaria, operating on behalf of one of the world’s largest Coca-Cola bottlers. Providing financial and HR support to 22 diverse countries, its 600 employees now aim to be best in class in terms of customer satisfaction. To realize this, BSO is leveraging the service design concept to introduce new ways of thinking and acting.

“If your business model became your prison, you’ve got to change your business.”

— Arne van Oosterom, Senior Partner and Co-Founder, DesignThinkers Group

Changing the emphasis

BSO was originally set up with a focus on enhancing processes from a compliance and efficiency point of view, adding extra steps to gain the trust of the different country operations. “This often resulted in cumbersome processes spread over many departments,” explains Business Services Director Simona Simion-Popescu. “This meant that the backbone of our services was not especially customer-oriented. And because the 22 country operations now see the added value of a shared service center, requests for even more services have added to the complexity of our operations.”

The challenge for BSO was to change the approach and the setup of its processes. “We needed to find a way to get things right from the outset when launching new projects and services so as to respect compliance and governance while providing an excellent experience for customers,” says Continuous Process Improvement Leader Vladimir Tsaklev, who is managing the project at BSO. “We needed to build an organization where there is a continuous focus on customer centricity and implementing in a sustainable way. This is where DesignThinkers Academy came in.”

Learning by doing