three

Potency

All hurricanes are catastrophic, but some are more catastrophic than others. This may sound glib to anyone who has experienced a real hurricane firsthand, up close and personal. But interested onlookers will be familiar with the use of categories to refer to the severity of a hurricane. This is particularly popular with the media in the United States and elsewhere, where hurricanes are tracked with some enthusiasm, using categories to emphasize their message. Sadly, there’s a tendency to use “category inflation” to increase the impact of the news story, with the potential severity of an incoming storm being overstated to provide a sensationalist angle. Many of us have heard consecutive media reports over a period of a few days something like this:

Initial bulletin: “Hurricane Anon is currently out in the ocean, bearing down on the mainland at high speed. At present it’s a strong Category 3 hurricane, and it’s expected to arrive in a couple of days, making landfall as a powerful Category 5. Mandatory evacuation will likely be imposed as considerable devastation is expected, with possible loss of life. This is not a drill; urgent action is required. A state of emergency could be declared at any time, and the National Guard are on standby.”

Next bulletin: “Get ready. Hurricane Anon is rapidly approaching our shores, strengthening all the time as it comes. Anon currently remains at Category 3, but it has the potential to become a full-fledged Category 5. This could be the Big One, the most dangerous storm since Hurricane Horrible 50 years ago. Residents are urged to take immediate action; time is running out.”

Final bulletin: “Hurricane Anon finally made landfall this morning as a Category 2 hurricane. While there was some initial disruption, the hurricane is expected to blow itself out over the next couple of hours, being downgraded to a tropical storm as it moves off into the ocean, where it won’t trouble us any further.”

The prominent (and often apparently unjustified) use of categories by the media emphasizes the fact that not all hurricanes are equal. But what are these categories, where do they come from, and what do they mean? And in the context of our analogy, are there also categories of Risk Hurricane, and how might they be defined or described? This chapter provides answers, explaining how to develop a Risk Hurricane Severity Scale that defines meaningful categories of Risk Hurricane for your organization.

CATEGORIES OF NATURAL HURRICANE

A hurricane is defined as a Force 12 storm in the Beaufort scale (see Table 1.1), which describes it in terms of wind speed and wave height. For convenience, Table 3.1 reproduces the full hurricane entry from the Beaufort Wind Force Scale.

Table 3.1: Hurricane definition in Beaufort Wind Force Scale

Beaufort scale, description | Force 12, Hurricane |

Wind speed | ≥ 118 km/h ≥ 73 mph ≥ 64 knots ≥ 32.6 m/s |

Wave height | ≥ 14 meters ≥ 46 feet |

Sea conditions | Huge waves. Sea is completely white with foam and spray. Air is filled with driving spray, greatly reducing visibility. |

Land conditions | Devastation |

This definition makes frequent use of the “greater-than-or-equal-to” sign (≥), clearly defining the boundary above which a storm can properly be called a hurricane. But this introduces a level of imprecision into the definition. For example, 75 mph is “≥ 73 mph,” but so is 150 mph, and the two are very different, although they are both hurricanes according to the Beaufort scale. The use of the single word “devastation” to describe land conditions is also somewhat terse and uninformative.

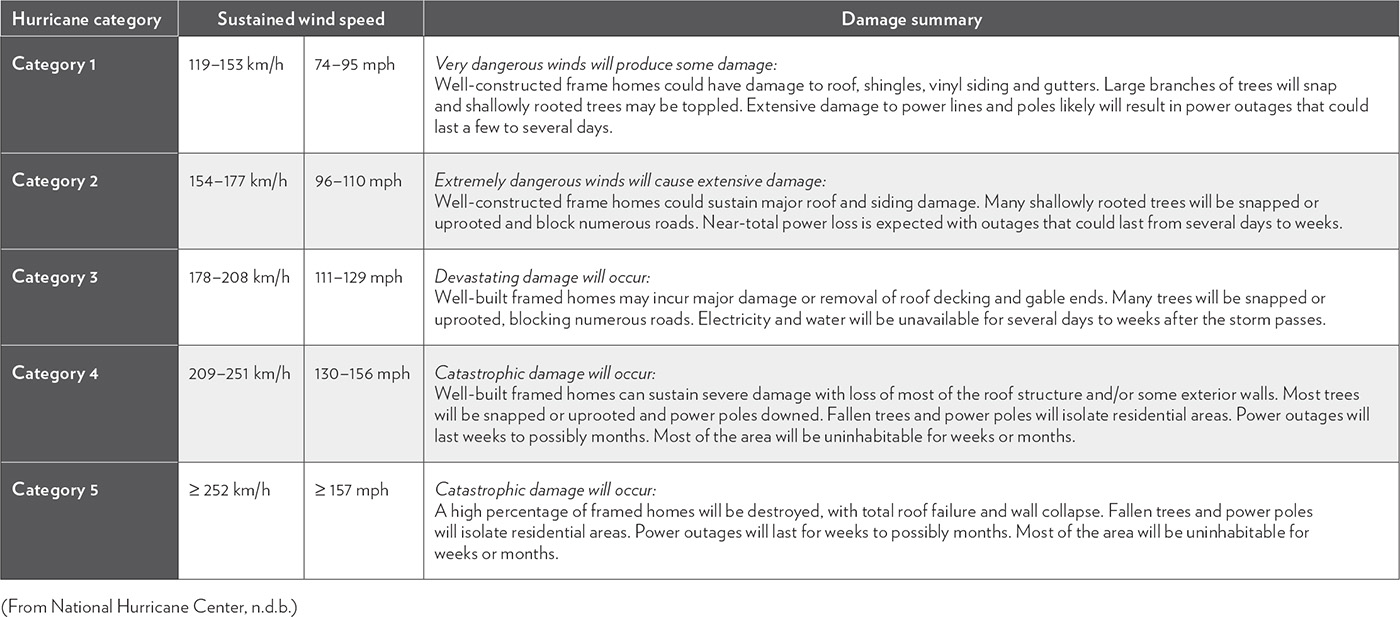

Ever since the Beaufort scale was first made public, meteorologists have wanted to be able to describe different classes of hurricane. The accepted international definition of the Beaufort scale published by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 2012 follows the original in having Force 12 as the highest level, but it also includes a set of widely accepted hurricane categories, based on work done in the mid-1970s by wind engineer Herb Saffir and meteorologist Bob Simpson. The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS) has five categories, based on sustained wind speed, as shown in Table 3.2.

Although Saffir-Simpson hurricane categories are formally defined only in terms of sustained wind speed, a brief indication of the expected level of damage is also provided as part of the SSHWS, as shown in Table 3.2. Initial versions of these high-level descriptors used only the headline generic terms (“some damage,” “extensive damage,” “devastating damage,” “catastrophic damage”), which give an idea of the severity of impact that each category of hurricane might cause. Although this is a start, it is not very helpful in practice to people who might be affected by an impending hurricane. What exactly is meant by “extensive damage”? When does the effect cease to be merely “devastating” and instead become “catastrophic”?

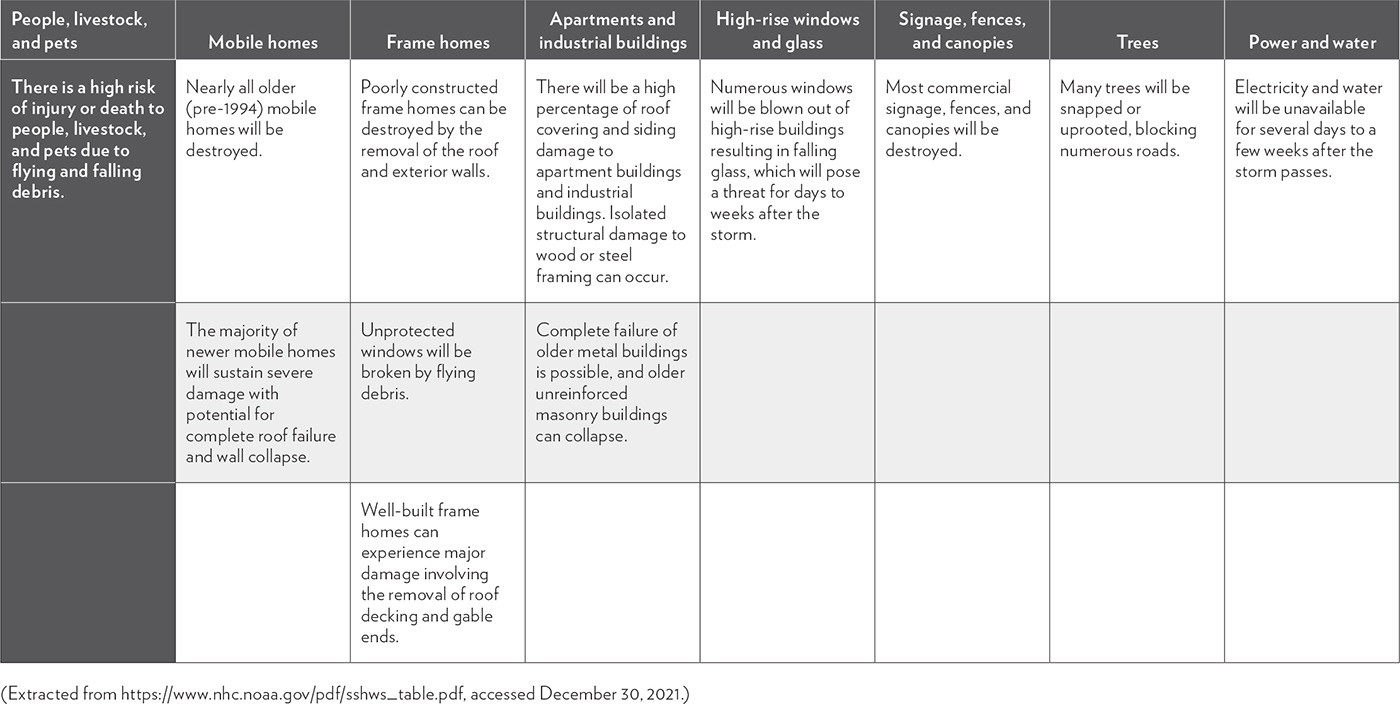

To address this ambiguity, more complete descriptions of each category were provided by the US National Hurricane Center, as shown in Table 3.2. These have been further developed into the so-called extended Saffir-Simpson scale. This takes each generic phrase and expands it to describe the degrees of expected damage and injury affecting a range of specific areas, including people, livestock and other animals, buildings of different types (mobile homes, frame homes, apartment blocks, industrial buildings, high-rise buildings), trees, fences, power, and water supplies. These scales provide more detailed indicators of likely damage, showing that the severity of the impact depends on the characteristics of the affected area. An example of these definitions of damage types is given in Table 3.3, which shows possible impacts from a Category 3 hurricane, providing a measurable interpretation of what is meant by the term “devastating damage.”

Table 3.2: Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale

Using the extended Saffir-Simpson scale, people and businesses in the path of a hurricane can see what type of damage they might expect, given the predicted hurricane category, allowing them to prepare appropriately. The goal is to enable appropriate responses to be taken in advance of the arrival of a hurricane. For example, if you live in an older mobile home that’s close to some trees and you own a couple of horses and a Category 3 hurricane is forecast to move through your area, you need to evacuate your home and move the horses. Or if you own a high-rise industrial building, you can refer to the table of likely impacts and decide to reinforce your windows and move equipment away from vulnerable areas.

In this way, the extended Saffir-Simpson category descriptions are more useful to people than the formal definition in terms of wind speed (“Category 3 will bring sustained winds of 111–129 mph”), or even the high-level description (“Devastating damage will occur” from a Category 3 hurricane). People can simply review the headings in the extended impact table to determine which ones are relevant to their situation then check the detailed impact statements.

CATEGORIES OF RISK HURRICANE

Taking the lead from our analogy, it’s possible to define different levels of risk exposure that cause business disruption. In the same way that the extent of likely damage against various criteria is used to specify Categories 1 through 5 of natural hurricane, so we can set up definitions of various classes of impact to determine the severity of a Risk Hurricane. We might even take the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS) and produce an equivalent for Risk Hurricanes: the Risk Hurricane Severity Scale (RHSS).

Table 3.3: Illustrative extended impacts from a Category 3 natural hurricane (“devastating damage”)

Table 3.4: Risk Hurricane Severity Scale

Risk hurricane categories | Risk exposure | Impact summary |

Category 1 | 20–50 percent chance of failing to meet one key strategic objective | Significant business disruption |

Category 2 | 20–50 percent chance of failing to meet more than one key strategic objective | Major business disruption |

Category 3 | > 50 percent chance of failing to meet one or more key strategic objectives | Extreme business disruption |

Category 4 | > 50 percent chance of failing to meet all strategic objectives | Catastrophic business disruption |

Category 5 | Imminent business collapse | Existential business disruption |

At its simplest, this is a generic description of the severity of a Risk Hurricane, expressing degrees of “risk exposure that leads to business disruption.” The Saffir-Simpson scale gives two types of information for each category: the wind speed and a summary statement of damage severity (see Table 3.2). In a similar way, the Risk Hurricane Severity Scale describes levels of risk exposure and a summary statement of the disruption to the business. Table 3.4 provides a generic set of categories of Risk Hurricane, with risk exposure expressed as the probability of failing to achieve key objectives, and simple terms to reflect the level of business disruption that would follow.

It’s important to note that the Risk Hurricane categories in Table 3.4 are defined in terms of the impact on strategic objectives and the consequential disruption to the business. These factors are independent of the nature of the risk, so it doesn’t matter whether your business is being affected by standard risk types that could be predicted in advance or by unpredictable types of emergent risk. The important thing to consider when trying to categorize a Risk Hurricane is to get a feel for how severe it might be, however that impact might arise.

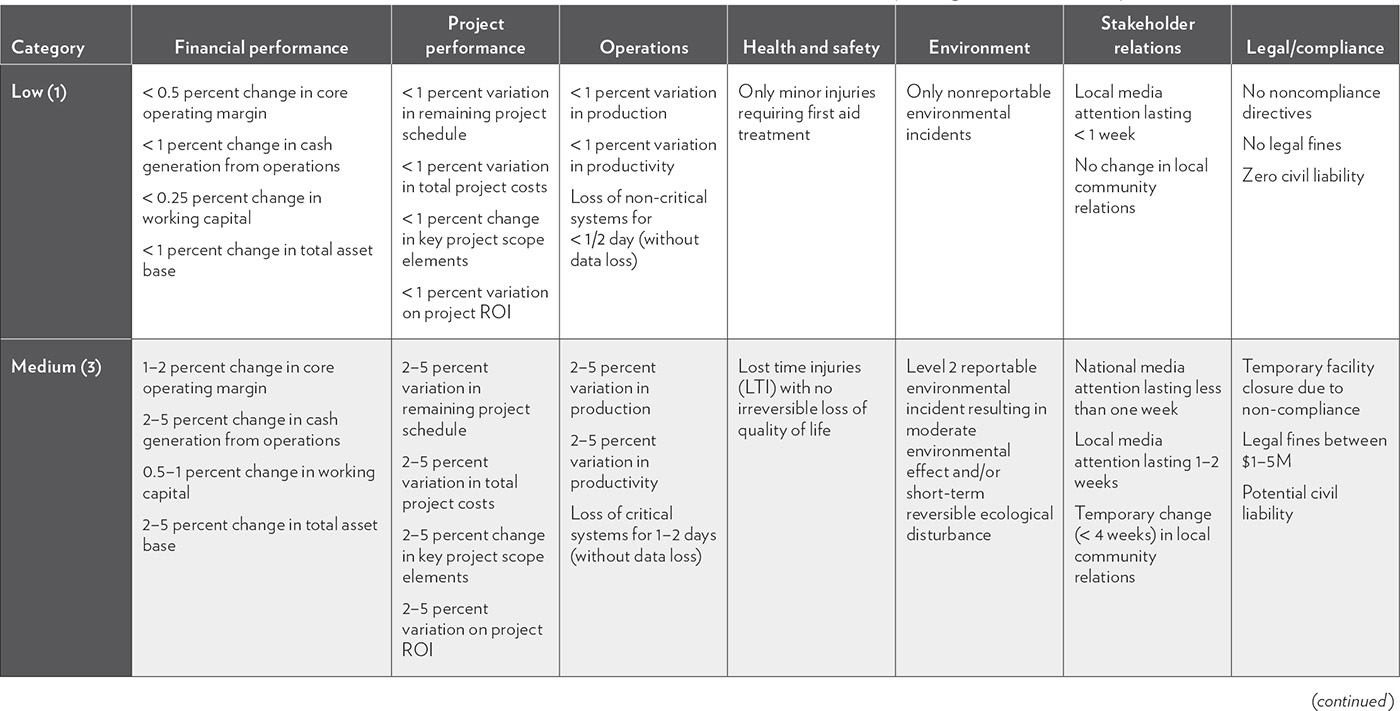

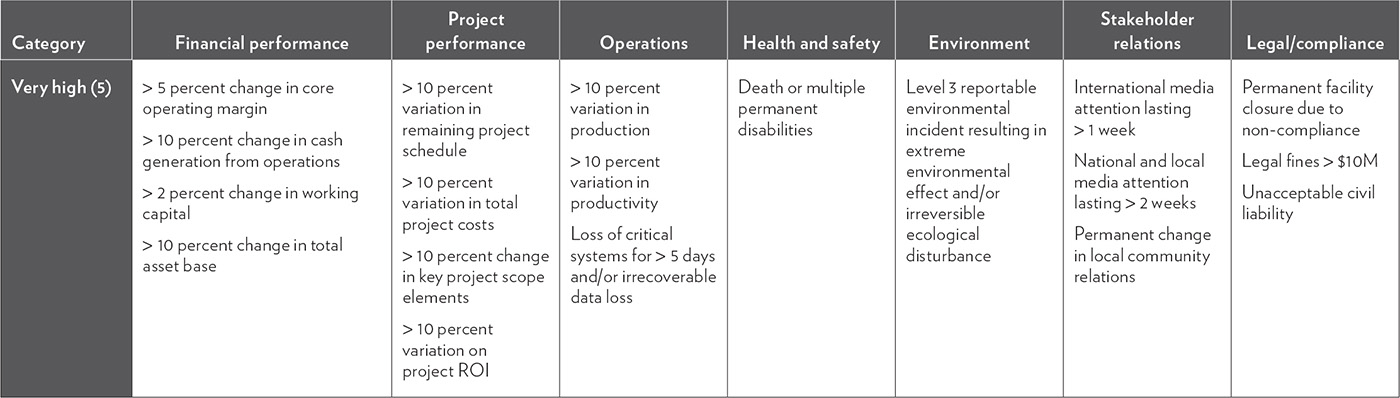

While the high-level descriptors of impact in Table 3.4 have some value in telling business leaders what they might expect from different categories of Risk Hurricane, they don’t help you decide what to do for your own organization. What precisely do you mean by the terms “significant,” “major,” “extreme,” “catastrophic,” and “existential”? It’s clear that the meanings of these words will differ from one organization to another. More detail is required, putting flesh on the bare bones of these generic impact statements, similar to the way the extended Saffir-Simpson scale describes possible levels of damage in different situations (Table 3.3). To develop an extended Risk Hurricane Severity Scale, we first need to define specific and relevant impact types that are meaningful to the business and then expand the simple generic terms in Table 3.4 to determine the meanings of Categories 1 through 5 for each impact type.

In the same way that different types of effect are relevant to different groups of people for a natural hurricane, the specific impacts of a Risk Hurricane on an organization will differ between businesses of different sizes, industries, locations, and so on. As a result, it’s not possible to provide a generic “extended Risk Hurricane Severity Scale” that applies to all types of business. We can, however, offer some guidelines on how such a set of impact types and definitions might be developed.

To do this, we need to go back to the simple definition of risk outlined in Chapter 1: risk is “uncertainty that matters.” Different things matter to different organizations, and what matters is captured and expressed in their objectives. At the highest level, for the business as a whole, strategic objectives define the goals by which the organization will measure success, and they set the overall targets for the business to achieve. Strategic objectives are then decomposed into lower levels to produce a hierarchy of objectives, which explains in increasing detail what the various levels of the organization must do in order to deliver the overall strategic objectives.

We can therefore define the types of impact from a Risk Hurricane that are important to our organization by linking them to our strategic objectives. Then for each objective, we can interpret the five impact levels in the generic Risk Hurricane Severity Scale in Table 3.4 (“significant,” “major,” “extreme,” “catastrophic,” “existential”). An example is shown in Table 3.5, taken from an organization in the energy sector that has implemented this approach. First, the business defined a set of seven specific impact types against which it wished to measure the effect of a Risk Hurricane (financial performance, project performance, operations, health and safety, environment, stakeholder relations, legal/compliance). Then for each category, five levels of impact were developed, presenting measurable criteria that the organization could use in practice. Table 3.5 shows an extract from the overall set of definitions for a Risk Hurricane, describing what this particular organization means by Category 1 “significant business disruption,” Category 3 “extreme business disruption,” and Category 5 “existential business disruption.”

When you’re developing these detailed impact scales for your organization, it’s important to remember that the highest category of Risk Hurricane only occurs rarely (as is also true of natural hurricanes: only 4 percent of hurricanes since 1851 have been Category 5). If a Category 5 Risk Hurricane were ever to happen, the disruption would be existential (meaning that the business will cease trading), and the measurable criteria in the detailed impact scales must truly represent this. It can be hard to consider such conditions, even harder to write them down, but they reflect a severity of corporate crisis that you hope will never happen.

Once you’ve defined levels of impact against each strategic objective, you can then roll this out to different levels of the organization (functional, departmental, operational, project, etc.), creating tailored definitions of impact at each level that reflect the overall impact levels for the whole organization.

USING CATEGORIES

In the case of both natural hurricanes and Risk Hurricanes, the ability to label them using Categories 1 through 5 serves two purposes:

1. Attention. Despite the sensationalist tendencies of some media, it’s helpful when communicating about an approaching natural hurricane to be able to distinguish between a relatively less severe Category 1 and a potentially catastrophic and life-threatening Category 5. Similarly, the existence of agreed severity scales can focus attention on an impending Risk Hurricane, making sure that business leaders, staff, and other stakeholders understand when something really bad may be about to happen.

Table 3.5: Illustrative extended impacts for a Risk Hurricane (Categories 1, 3, and 5)

2. Action. Just knowing that something is coming toward you doesn’t necessarily help you to survive the oncoming storm. You need to turn attention into action if you’re to make use of the information being provided to you. The extended Saffir-Simpson scale provides clear guidance to affected individuals and groups about what they might expect from a particular category of storm and what they should do to prepare and protect themselves and their property. Businesses facing a Risk Hurricane can also develop and use an extended Risk Hurricane Severity Scale to predict what impact might affect achievement of your strategic objectives, allowing you to take appropriate and proactive action in advance of the arrival of any expected disruption.

CASE STUDY: COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Let’s look at an example of how categories of extreme disruption work in a real example.

Like the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 discussed in Chapter 2, the COVID-19 global pandemic was clearly a Risk Hurricane whose effects are still being felt across the globe. It’s likely to become a standard case study in how to handle extreme risk exposure that leads to major disruption (or perhaps how not to handle it), and it could serve as a worked example for each chapter in this book. Here we focus on how we could have used agreed categories to understand and define the severity of the COVID-19 Risk Hurricane.

The disease known as COVID-19 is caused by a novel respiratory coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan City in China in late 2019. Early studies showed that it was a variant of the SARS coronavirus that caused Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in 2003, and the new virus was officially named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (WHO) in February 2020. Restrictions on public mobility (“lockdown”) were introduced in Wuhan in an attempt to contain the spread of the virus, but by March 2020 the WHO had declared a global pandemic. By April 2020 over half the world’s population was under some form of lockdown, with measures introduced to limit social mixing, use of facemasks to reduce person-to-person transmission, quarantining of infected persons, and tracing of their recent contacts. According to the WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard (World Health Organization, n.d.), by the end of 2021 over 270 million infections had been reported in over 200 countries worldwide, with over 5.3 million deaths attributed to COVID-19, making this the deadliest pandemic in recorded history.

Initial responses from national governments around the globe varied widely in the early days, with no consensus on the most effective approach. Some acted very quickly to introduce stringent measures, notably South Korea, where in February 2020, national mass screening and localized quarantines were implemented, infected individuals were isolated, and their contacts were traced and quarantined. International arrivals were also required to quarantine from April 2020, with a cellphone app to support mandatory self-reporting of symptoms. Current data in December 2021 (World Health Organization, n.d.) show that for total deaths due to COVID-19, South Korea ranks around 170 out of over 200 countries in proportion to its population.

By contrast, Brazil’s government has been criticized for its slow response to the pandemic. In March 2020 President Bolsonaro condemned “media hysteria” about the novel coronavirus and declared, “For 90 percent of the population, this will be a little flu or nothing” (France24, n.d.). One year later, he was still opposing mask-wearing, casting doubt on vaccine effectiveness, and suggesting that the pandemic was “being used politically, not to defeat a virus, but to try to overthrow a president” (France24, n.d.). Brazil currently ranks eleventh in the world for deaths attributed to COVID-19.

One reason for this wide range of responses to the coronavirus pandemic in its early stages is that there was no agreed way of assessing its severity. Scientific data were still emerging, and expert opinion varied on the best approach to mitigation and treatment. When combined with very different political environments and styles, it’s unsurprising that the responses of governments and their populations were so varied.

It would have been helpful if, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, a global body such as the WHO had defined severity categories for its possible impacts. National governments and others could have used these scales to assess how big this particular Risk Hurricane could be, allowing them to design and implement appropriate treatment strategies and monitor the effectiveness of these approaches in controlling the pandemic among their populations.

Earlier in this chapter we showed how to develop categories for business-related Risk Hurricanes, similar to Categories 1 through 5 for natural hurricanes. Table 3.4 gives high-level generic descriptors of increasing severity, expressed in terms of the probability of failing to achieve key strategic objectives, and the level of business disruption that would follow. It would be possible to adjust the nature of these two main scales to develop broad categories for a health emergency such as a pandemic, for example, defining the likelihood of a population experiencing a given level of infections or deaths, combined with the effect on national well-being.

However, the generic scales in Table 3.4 contain terms that are qualitative and ambiguous: significant, major, extreme, catastrophic, and existential. While these provide some sense of increasing severity and allow you to assess the likely category of a Risk Hurricane, to be properly useful it’s necessary to expand these terms into more detail, as shown in Table 3.5. This uses measurable impact types that are linked to strategic objectives.

In the early days of the pandemic, initial assessments of COVID-19 risk by governments, their scientific advisers, and populations were broad-brush, using generic terms such as “critical” and “dangerous,” or “trivial” and “minor.” These vague expressions led to ambiguity, confusion, and lack of focus, as well as allowing people to adopt a range of varying interpretations of the same term. In the same way that the generic definitions of Table 3.4 are expanded into more detailed impact statements in Table 3.5, it would have been helpful for national governments to have access to an agreed-upon extended set of definitions of possible impacts of the pandemic against different areas of society, including physical health, mental well-being, health service capacity, economic performance, business viability, employment levels, supply chain reliability, community cohesion, and so on.

Each of these could then be expressed using quantifiable measures, such as:

• Number of infections per million of population

• Number of deaths per million of population

• Reproduction number (R), expressing how many people will get the virus from each infected person, on average

• Percentage hospital beds occupied by COVID-19 patients

• Percentage intensive care unit (ICU) capacity used by COVID-19 patients

If agreed severity scales for the COVID-19 pandemic had been published by WHO early on, there would be no confusion or debate over how severely a particular nation was affected. Subjectivity would be removed in favor of objective measurable data. But without an agreed-upon set of categories for the COVID-19 pandemic, based on defined and measurable levels of impact severity, different national governments had to make their own judgments of what they were facing and how they should respond. They were influenced by a complex web of perceptions and pressures and inevitably came up with a range of approaches, from aggressive to passive, and everything in between. It wasn’t possible to have a sensible debate about the size or significance of the pandemic or to monitor and measure its waxing and waning, because there was no common language in place. Sadly, this situation remains unchanged at the time of writing, despite the emergence of new COVID-19 variants, where such a system of categorization would prove useful in assessing the associated risk to determine whether a new strain is a variant of interest or a variant of concern, and the extent to which we need to worry about it. Agreed-upon categories also simplify the task of communication with the public and allow changes in the level of risk exposure to be monitored as each wave of infection develops and passes.

CLOSING CONSIDERATIONS

Risk Hurricanes are not all the same; some are more potent than others. Different levels of natural hurricane can be described using recognized categories, and this chapter has shown how we can define categories of severity for Risk Hurricanes, both in general terms and using specific measurable impact scales. These categories are useful for focusing attention on the most severe potential sources of business disruption, as well as helping business leaders to understand what action might be appropriate.

Business leaders can take the following two steps to create specific severity categories for assessing potential Risk Hurricanes:

1. Clearly define strategic objectives, with measurable thresholds that reflect your organizational risk appetite.

2. For impact against each objective, determine what the following terms might mean for your organization: “significant,” “major,” “extreme,” “catastrophic,” “existential.”

With these definitions in place, you’ll be able to distinguish between levels of risk exposure that would cause significant disruption to your business and those that pose an existential threat, linked to an understanding of which strategic objectives are most likely to be affected. And when you know how potent an impending Risk Hurricane could be, you can then start to plan appropriate actions to prepare and protect your business in advance.