CHAPTER 6

De Colores: Culturally Centered Leadership

LATINOS ARE A RICH culture of synthesis and fusion. With such a colorful array of fiesta-loving, family-centered, hardworking, tamale- and salsa-eating Latinos, one might wonder what could possibly keep this sundry group together. What are the connecting points that give a shared identity to this cohort of thirty distinct subgroups in the US census?

Much like the Jewish community, Latinos are an ethnic and cultural group. Latinos are bound together by the Spanish language, a shared history, a spiritual tradition, and common values that stem from both their Spanish and their Indigenous roots. Cultural values are fastening points—the nucleus—shaping a collective identity from the many ingredients of the delectable Latina familia. As Arturo Vargas, president of the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials, observes, “I’ve met Latinos all over the country, and diverse as Latinos are, there’s a set of core values we hold. It’s about family, and the face of their children, and the face of the future. There’s a level of optimism and a sense of community.”

This chapter highlights seven key values: familia, simpático (being easy to get along with), generosity, respect, honesty, hard work, and service to others. The central value of faith is explored in chapter 7. These deeply intertwined values form the substance of Latino leadership. Hilda Solis notes, “My leadership is based on my upbringing and cultural values—what I was taught as a young child.”

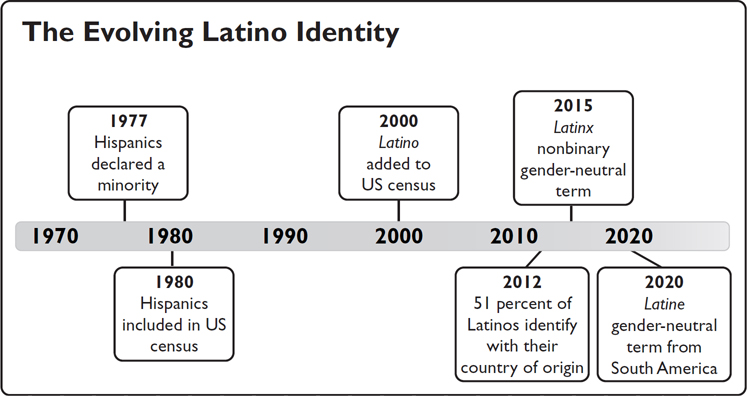

Before delving into cultural values, let us explore the multifaceted Hispanic identity. Since our vast diversity includes many nations of origin and mixed-race ancestry, there remains the puzzling question about exactly what it means to be Latino. The story of how Latinos came to be recognized as a cultural and ethnic group offers historical insights into the racial underpinnings of the US census.

Latino, Hispanic, Mexicano, Cubano, Latinx—Who Are You?

FILLING OUT MY FIRST US census form in 1970, I searched for a category that would acknowledge my culture and ancestry. I felt a loud thud in my heart as I finally checked the “Caucasian” box. As I filled out the forms, I heard my abuela’s sweet voice, “Ay, mi hijita, nunca olvides quien eres y de donde venistes” (Oh, my dearest little daughter, never forget who you are and where you came from). But remembering your history and embracing your identity is a difficult feat when there is no acknowledgment that your people even exist.

We all have a deep need to know who we are. This is particularly true for Latinos and other people of color, who have been relegated to a minority status and measured by a White ideal. As we have noted, Latinos are de colores (of many colors) and have a bienvenido spirit—they are inherently inclusive and diverse. The mainstream culture, on the other hand, values homogeneity, uniformity, and categorization.

The story of how the “Browns” (Hispanics) became a category in the US census illustrates the unique history of this cultural medley. (Of course, members of other ethnic groups, such as South Asians, Pacific Islanders, Middle Easterners, and Native Americans, may also consider themselves Brown, but we are using Brown to refer to Hispanics and Latinos.)

Adding “Hispanic” restructured the census categories to offer many more choices for racial and ethnic identities and tilled the soil for our emerging multicultural identity. In fact, according to the 2020 census, the “Two or More Races” population (also referred to as the multiracial population) is now almost 34 million people—a 276 percent increase since 2010.1

The Evolving US Census

FROM THE EARLIEST DAYS of the Constitution, one of the ways the US government categorized people was by race and color. This was enumerated and sanctified by the US census, in which every ten years census counters scoured the countryside, tallying the people that made up this great land. After the national count in 1970, the census counters, pulling their hair in frustration, asked, “What do we do with this disparate group, the Browns, who are reporting all kinds of concoctions? They were supposed to check one of the existing four categories: Caucasian, Black, Asian, or Native American!”

The Browns were identifying themselves as Mexican, Cuban, and Spanish (in the Southwest, many trace their heritage to the Spanish land grants). Others identified themselves by the place they, or even their grandparents, were born, such as Brazil, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, or Puerto Rico. The list was ve-e-ery complicated, because the Browns had kinship with twenty-six countries, and indeed they liked to mix it up!

The census takers were quickly finding out that the Browns valued something called personalismo, which meant everyone was único—an individual with a story to tell. Diversity and differentiation were core to their identity.

Then the census bureaucrats had a bright idea: let’s ask them what they want to be called. A big council was organized in the nation’s capital, and leaders from the Browns were flown in. One was Leo Estrada of UCLA, a leading demographer.2 The census counters thought he would know what to call these people, since he was one of them. The leaders deliberated for a very long time. Finally, in the wee hours, a compromise was reached. The government could use the term Hispanic, referring to Hispania, the old Roman name for Spain. Hispanic was English, not a Spanish word, so the census counters were muy contentos (content or happy)!

So it came to pass that President Richard Nixon’s OMB Statistical Directive 15 ordered the addition of a Spanish-origin self-identifier to the 1980 census.3 From then on, there would be five colors in the American palette. The conglomerate of people spanning five hundred years of the mestizaje was baptized Hispanic.

Just Check the Box

THE DEBATE AMONG HISPANICS, however, continued, reflecting their diversity and the difficulty of finding one Communion wafer everyone could swallow. Many prefer the term Latino, even though it can be traced to the Roman occupation of Spain centuries ago. Latino is politically and culturally a more useful term because it connects people to Central and Latin America and unites them through culture, kinship, and the Romance languages. And it is a Spanish word. Latino was added as a designation in the 2010 census.4

For the census takers, the saga of the naming of Hispanics continued like a roller coaster on Coney Island. Since Hispanics are an ethnic group and not a race, they can be Black, White, Yellow, or Red. The census takers took out their racial microscope and surmised that all the categories needed to change to really capture the essence of America’s genetics. People now had to indicate their race based on their non-Hispanic identity—White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, American Indian, Eskimo and Aleut non-Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander non-Hispanic.

Hispanic, which was once a strange mutt that needed a name and had been excluded from the census from 1790 to 1980, now became the standard-bearer for all other racial delineations, giving new meaning to the biblical phrase “The last shall be first.”

Unlike African Americans, Native Americans, or Asian Americans, whose blood content defines them, Latinos are the only group that self-identifies. According to F. James Davis in his book Who Is Black?, anyone with any known Black African ancestry is considered Black.5 In the racist South, this was the basis for the “one-drop rule,” which came to mean that anyone with any Black blood was considered Negro. Native Americans have blood quantum, imposed by the treaties, which means a person must have legal proof of their bloodline to be enrolled in a tribe. Asian refers to a person with origins from any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.6

On the other hand, according to the US census, “An individual’s responses to the race question and to the Hispanic origin question were based on self-identification.”7 This was reinforced by the Pew Research Center in a 2021 article entitled “Who Is Hispanic?” According to the article, the answer to the titular question is “Anyone who says they are. And nobody who says they aren’t.”8

It could be said, then, that to identify as a Latino you simply check the box on the census. Raul Yzaguirre surmises, “America needs a different paradigm of what it means to be Latino. The prototype of the Native or African Americans, where your blood content defines who you are, doesn’t work. Latinos are a culture, not a race. Culture, it must be remembered, is learned and not inherited. My definition of Latino is anybody who wants to be a Latino. Bienvenido—welcome to the family.” (The invitation to become a Latino by affinity, or corazón, will be considered in chapter 13.)

While many non-Latinos might be confused by this definition, more than 62 million Americans, or 19 percent of the population, identified as Hispanic in the 2020 census. This validates Latino heterogeneity and the ability to incorporate differences into a common cultural core.

To gain a better understanding, let’s explore the dynamic values that unite Latinos and frame this diverse culture. These values are also the driving force for the people-centered leadership of the Latino community.

La Familia—A We Orientation

TRADITIONALLY IN SPAIN, LARGE extended familias lived in the same community for generations and relied on each other for daily essentials and special needs. Likewise, in American Indian cultures today, as with previous generations, the tribe takes care of its members, land is held in common, and everyone is seen as a relative. The Aztec civilization was made up of multiple ethnicities and organized into small family groups who governed themselves and worked together as a unit. Thus, the many roots that nourished the Latino tradition had strong family ties and community bonds.

These ancestral connections anchor a We, or collective, orientation. We cultures have been on the earth for a very long time. Tightly woven, stable, and integrated, We cultures center on group welfare, interdependence, and cooperation. The family, community, or tribe takes precedence; individual identity flows from the collective. People work for group success before personal gain or credit. It is no wonder that Latinos cherish belonging, mutual benefit, and reciprocity.

We cultures revolve around people-centered values. For Latinos, these values include generosity, being of service, and respecting others. To keep relationships strong (the fabric of We cultures), Latinos strive for unity, harmony, and pleasant social interactions. They like politeness and good manners.

The We orientation is evident in the familia, which is not exclusively bonded by blood or legal relationships but broadly refers to a group with a special affinity for one another. The familia is e-l-a-s-t-i-c and expands to include padrinos or madrinas (godparents) at baptisms, weddings, confirmations, and other special events. Tíos and tías are honorary aunts and uncles and close family friends. Primos, or cousins, include anyone who is even vaguely (and sometimes mysteriously) connected to your family. Ask who someone is that you don’t know at a family reunion and a common response is “Es tu primo.” And this is accepted.

Then again, while you’re simply walking down the street with a close friend, another person might suddenly be introduced as a compadre or comadre, indicating that he or she is now part of the familia. This goes unquestioned, as family connections are elaborate and expansive where close friends are considered relatives. I just became a tía abuela (grandmother aunt) to my goddaughter’s baby. I always like to add that these relationships imply responsibility, meaning you are expected to assist when a need arises, which can range from contributing to weddings and special occasions to providing emotional support.

This tradition of open and inclusive family relations reflects the bienvenido spirit, which means to receive or accept with pleasure, approve or appreciate, even embrace. The bienvenido spirit is the source of Latino hospitality, generosity, and receptivity to differences. Bienvenido welcomes immigrants into the Latino community and is the wellspring for an intergenerational approach to leadership. (More on this in chapter 9.) Bienvenido invites non-Latinos to partake in the culture and become part of the familia as Latinos by corazón. Latino leadership centers on this We, inclusive, or other-centered orientation encapsulated in the bienvenido spirit.

Hispanic Value: Simpático—Being Congenial

¡QUE SIMPÁTICO! IS A prized Latino compliment. It means people think you are likable, easy to get along with, and charming. Having smooth social relationships is of biblical importance to Latinos, who tend to acquiesce to the wishes of others in order to be seen as congenial. Being respectful and courteous, making small talk, and taking a personal interest in people are ways to be simpático—coveted traits in a people-come-first culture.

When Latinos enter a room, for instance, the polite thing for them to do is to say hello to each person, inquire how that person is doing, and ask about his or her familia. When leaving, Latinos make the rounds again, this time expressing how good it was to see everyone. (“Con permiso”—with your permission—requests approval to make an exit.)

“Relationships take time” could be a Latino mantra. At some events, everyone in the room has to be recognized and thanked, which means things can go on and on and on. This is when the observance of LST, or Latino Standard Time—time that revolves around connecting with people and not just getting things done—tests your good manners.

In surveys, Latinos respond that they tend to carry out socially desirable actions and attitudes.9 A person who is bien educado, for instance, is polite and gracious and takes people’s feelings into consideration. The literal translation of bien educado would be “well educated.” However, for Latinos it means a person was raised right! How a person treats others (personalismo) is more important in garnering respect than university degrees, wealth, achievements, or the status symbols a person has attained.

People who are simpático are usually good at recognizing and complimenting people’s special traits and contributions.10 Latinos call this echando flores—literally, “giving people flowers.” Verbal flores express gratitude and celebrate a person’s achievements. The genuine affection Latinos show toward one another helped sustained them through centuries of living in a society that undervalued their contributions or misunderstood their cultural effusiveness. Acknowledging people’s good qualities and accomplishments is an essential ability for Latino leaders.

Hispanic Value: Generosity and Sharing

My sister Margarita was raised in Nicaragua and was culturally more traditional (or less assimilated) than I am. When I was in my thirties, she was visiting when my next-door neighbor dropped by. He casually admired a poncho hanging on the wall. “Gracias,” I said, and I smiled as I remembered its origins. “It’s handwoven, and I got it in Chile.” When he left, my sister scolded me. “Have you forgotten everything you were taught? You were supposed to give him that poncho!”

This jostled my memory, and I flashed back to a fiesta a few years earlier, when Margarita lived in Guatemala. The hostess flung open the door and gave me a big abrazo (embrace), even though I had never met her and hadn’t really been invited. “What beautiful gold earrings,” I gasped, somewhat stunned at her generous welcoming.

“Here,” she said. “You must have them—they’re yours.” Then she smiled, took them off, and handed me the treasured gift without a moment’s hesitation.

The Latino saying “Mi casa es su casa” is the first commandment of generosity. It encapsulates the joy in sharing and implies “What I have is also yours.” In collectivist cultures, possessions are more fluid and communal. People take pleasure in giving things away. Generosity, however, is not just a two-way street; it is a busy intersection where everybody meets. A good illustration is the way strangers are always made to feel welcome. One can rest assured that this kindness will come back to you. Even if a particular individual never reciprocates, someone else will surely return the kindness one day.

Latino fiestas are a testament to collective hospitality. All who attend bring gifts, flowers, food, wine, and special treats to share. Many times, when I have a social gathering, it is something akin to the parable of the loaves and fishes in the New Testament. Everyone contributes and the food keeps coming—there is more to eat and drink at the end of the fiesta than at the beginning. For weddings, graduations, and special celebrations, there is the tradition of being a madrino or madrina (sponsor) and paying for the photographer, banda (band), cake, or bar. At Mexican weddings, people pin money on the bride’s dress or pay to dance with the bride or groom.

In traditional families, it can be embarrassing to “have more” or to advance ahead of the group. Having more means a greater responsibility to share more (which is not a burden, but a task undertaken with grace and kindness). When my brother John became a successful music executive, he was the go-to person when a family member had a special need, such as money for school or for travel expenses to attend a family reunion. Cooperation, sharing resources, and helping others keep ties solid.

Generosity is the glue that holds We cultures together. Mutuality ensures that people give to each other, and everyone is taken care of. Almost unanimously across collective cultures, it is understood that the accumulation of vast wealth and power by a few hinders the well-being of the community as a whole. People taking more than their share, and the sharp accumulation of money by some at the expense of others, rips apart the community fiber. For this reason, true wealth is defined as being able to give to others.

Unless one has experienced contagious Latino generosity, people from individualistic cultures may find it difficult to understand or to aspire to this level of sharing. From a We perspective, since the self emerges from the collective, generosity toward others is actually giving to oneself.

Latino Value: Respeto—Showing Respect

Latinos believe everyone should be treated with dignity and courtesy, regardless of wealth or status. The belief that every person has inherent worth resonates with their people-come-first values, which was highlighted in the section on personalismo. And as we will see, this is the foundation for the leader as equal.

Prolific movie producer Moctesuma Esparza, whose credits include The Milagro Beanfield War and Selena—a tribute to “the queen of Tex-Mex music”—emphasizes, “Along with respecting elders, a quality my father passed on to me was to treat everyone the same, that is, with respect, no matter what their station in life was, no matter whether they were a president, a rich person, a farm worker, a dishwasher, or anyone else.”11

While everyone is treated with respect, being looked up to depends on how a person lives, acts, and treats others. Latinos show respect through their body language, tone of voice, deference, apologies, and explanations (even when not really warranted). Of course, all this is interwoven with behaving courteously, offering profuse thanks, and giving compliments. Mutual respect fosters harmonious relationships, cooperation, and reciprocal support.

Respect is even more important with elders and people in positions of authority, such as doctors, priests, teachers, and leaders. They respect a person’s title, contributions, education, or authority.12 Paradoxically, people in positions of power must not assume airs or act as though they are better than others, or they will lose this respect. Plumbers, electricians, bricklayers, gardeners, and people in many trades are respected as well. Someone who is good at a craft or profession is called maestro, or master, indicating they are eminently skilled at their craft. The beautiful work many Latino laborers and tradespeople do is indicative of the pride they take in being maestros.

Latinos may communicate indirectly and circuitously if it will spare a person’s feelings. Again, this is somewhat paradoxical, since honesty has such a high value, but in this case, courtesy has a higher one. Ask a Latino for directions, and of course they will try to help. You are probably going to get into a conversation even if they don’t have a clue where you are going. Taking time to be friendly and maintaining congenial relationships is the best way to ensure that Latinos will participate, be committed, and give well-thought-out, honest responses. These are building blocks for people-oriented leadership.

Hispanic Value: Ser Honesto—Being Honest

Latinos honor the oral tradition. Agreements made verbally were considered just as binding as legal documents. Traditionally, Latinos did not rely on lawyers or contracts to make agreements or do business—a word and a handshake were sufficient. This worked because people usually knew each other or had mutual acquaintances. As Carlos Orta has observed, even today, “Latinos have to get to know a person and trust them before they can do business with them. Latinos don’t do business from a transactional perspective but from a relational one.”

When buying a service or making an agreement to purchase something, Latinos will routinely not ask for the money or talk up front about costs. This reflects trust in the person’s fairness and in the unspoken but binding agreement that they will keep their word. It is also a cultural test—to determine whether this person is honest and someone to befriend. (Of course, in the end, setting a fair price becomes part of the conversation. The essence of bartering is conversing, exchanging, and ensuring everyone feels good about the exchange.)

The phrase “hombre de palabra”—a man of his word—is like the Latino Good Housekeeping seal of approval. Keeping one’s word is a value upheld in many cultures and certainly is an indispensable leadership trait. But in We-centered cultures, the threads holding relationships together would unravel if people did not keep their word. People depend on one another for survival, and honoring commitments is essential.

Honesty or being truthful has been identified as the single most important ingredient determining a leader’s credibility because it engenders trust.13 The bankers letting their greed precipitate the housing and banking crises, politicians breaking their promises, corporate executives not accurately disclosing a company’s finances—all indicate that many leaders today simply do not tell the truth. Raul Yzaguirre characterizes honesty as aligning words with action: “There are a lot of inconsistencies with leaders today who articulate American values but don’t live them. Latinos are living their values every day. As a culture, we believe that you do what you say you are going to do.”

Hispanic Value: Trabajar—Contributing Through Work

Even though a growing number of Latinos are now middle class, historically most families, like mine, were working class. In fact, today Hispanics account for 17 percent of total employment but are substantially overrepresented as painters and construction and maintenance workers (36 percent); as miscellaneous agricultural workers (43 percent); and in food preparation and serving (27 percent).14 This is in part because immigrants often start at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Yes! Latinos continue doing all kinds of tedious jobs—putting on roofs in the searing summer sun, cutting lawns, digging ditches, cleaning hotel rooms, and cooking food. Many times, they might be listening to a radio blasting salsa or Mexican ranchera music, having noisy conversations, ribbing each other, or even singing a Spanish tune. What is it about Latinos that enables them to take jobs that people in other cultures might find “beneath” them and to be happy and singing while doing these menial and sometimes physically difficult tasks?

In a collective culture, where We is more important than I, work is not just a person’s livelihood; it is a way to take care of the familia. Since familia is the highest value and concern, work has meaning and dignity. A person will do what they have to do: “As long as I can feed my familia, I feel good about myself. I am honorable.” Perhaps for this reason, Latinos have an impeccable work ethic, which translates into the highest participation of any group in the labor market.15 Work is not just a job; it is a way to contribute to others. Latinos believe in the rewards of hard work. More than 8 in 10—including 80 percent of Latino youths and 86 percent of Latinos twenty-six and older—say that most people can get ahead in life if they work hard.16

The dicho “Los que no trabajan no comen” (Those who don’t work, don’t eat) underscores that everyone has the responsibility to work and to give of one’s efforts. Taking advantage of others by freeloading or not doing one’s share runs contrary to helping others. Doing a good job is also the main way to contribute to one’s employer. This connects to Latino generosity—what better way to share than to do one’s work with gusto—to give it your best shot!

An interesting dimension is that Latinos have traditionally not been part of the elite class; they have not attained benefits, reaped rewards, or assumed privileges they did not earn. They have gotten ahead through their own efforts, especially by working hard and proving themselves. Equality asserts that every person should contribute and earn privileges or rights. Chapter 8, “Juntos: Leadership by the Many,” builds on this by describing how to ensure that everyone has a place at the table and is invited to contribute.

Hispanic Value: Serving and Helping Others

The values described above converge into cultural directives that spell out how people should relate to and treat one another. We cultures emphasize taking care of and contributing to others.

When you first meet a Mexican American, she might greet you by saying, “A sus ordenes” (at your service). When a request is made, she might reply, “Para servirle” (I am here to serve, and how may I help you?). When someone asks for something, the response might be “Mande.” Mande literally means “Tell me what you want me to do.” The cultural translation is “I will do it if I can.”

These traditional responses are deeply rooted in the Latino Indigenous background and create a collective spirit where people “serve” one another. Consider that the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs had no word for the concept of I. Their sense of relatedness and helping others was the basis of their worldview. So, too, the golden rule of the Maya, “In Lak’ech,” signifies “You are in me, and I am in you.” This saying reflected their belief that human beings are one people and that what one does to another affects oneself.17

Serving is intricately linked to generosity, group benefit, and reciprocity. People understand that what they give to others will certainly come back to them. While it is not tit for tat and people do not expect anything in return, they know that the cultural covenant is to help one another. Cyclical reciprocity means that what you give will eventually circle back to you and that, by sharing, everyone will have enough.

In We cultures, relationships always imply responsibility toward others. This engenders a sense of duty and is evident in the work ethic I have described. Service is the nucleus around which Latino leadership revolves. Anna Escobedo Cabral has seen this tendency in her extensive work with Latino leaders: “Our ultimate motivation is a concern for the people we serve.”

De Colores—of Many Colors

IN THE 1960S, WHEN the humble farm workers marched with César Chávez, they sang “De Colores,” a traditional and beloved song that is thought to have been brought over from Spain in the sixteenth century. De colores literally means “of many colors.” The song celebrates the incredible beauty of diversity—the multicolored birds, the radiant garden flowers, the luminescent rainbow. The chorus of “De Colores” says that because life by its nature appears in so many colors, so too great love also comes in a multitude of colors.

The love of diversity in this song is deep within the Latino soul because Latinos are de colores. The many colors of humanity are part of our familia. While the US census took more than two hundred years to recognize the multifaceted Latino identity, the song “De Colores” clearly defined it centuries ago. We are a diverse and inclusive people that represent the beautiful colors of humanity.

As we noted, Hispanic identity also diversified the US census. Consider that the 2000 census was the first time people had the option to identify as more than one race. By the 2020 census, the “Two or More Races” (multiracial) population was almost 34 million people—a 276 percent increase since 2010. This is now the fastest-growing racial and ethnic category, and Latinos are leading this change.18

We have surmised that Latino destino is shaping the diverse and inclusive society. De colores offers a pathway to accomplish this—to integrate our kaleidoscope society and to embrace the gifts of all people, including every generation. Latinos offer an antidote to the exclusion, inequity, and homogeneity of the past. For this reason, I believe “De Colores” is the Hispanic national anthem.