2

Basics of Human Resource Development

CHAPTER OUTLINE

• Interplay between the Phases of the HRD Process

• Turning the HRD Intervention into a Fun Event

• Characteristics of the Key Players

Introduction

There is no single way to view Human Resource Development (HRD) or to go about HRD work. This chapter presents the underpinnings of HRD as a further orientation to its basic framework. The selection of HRD underpinnings is intended to illustrate, but it is not exhaustive. You should be prepared to expand on the ideas offered in this chapter as you progress through the book. These basic underpinnings serve to orient readers who are new to HRD and also refresh the thinking of those already familiar with the profession.

Points of Agreement

As with any field of theory and practice, there are rival views and intense debates. This is especially true among scholars. Satirically, scholars are characterized as spending 80 percent of their time debating about the 20 percent of a subject on which they disagree. Acknowledging differences is important, and this will take place throughout the book. Even more important is the need to point out areas of agreement. It is here that the solid core of HRD theory and practice can be found. In contrast, areas of disagreement create the tension required for serious reflection and inquiry that ultimately yields renewal and advancement.

HRD is an evolving discipline. This makes for exciting debates within the profession. It is important for those engaging in and listening to these debates not to lose sight of their points of agreement. Four overriding points of agreement include belief in human potential, the goal of improvement, a problem-solving orientation, and systems thinking.

BELIEF IN HUMAN POTENTIAL

“Some Humans ain’t Human” is a song written and performed by John Prine (2005). While Prine explores the dark side of humanity through song, HRD professionals try to head off problems in organizations and explore the positive side. Pragmatically, not ideologically, HRD professionals advocate for human potential, human development opportunities, and fairness. HRD professionals are proud of their humanity and talk about humans and humaneness in ways that few other business professionals do (Chalofsky, 2000). Human resource development professionals are unique in this respect, even when compared to their human resource management (HRM) counterparts.

GOAL OF IMPROVEMENT

The idea of improvement overarches almost all HRD definitions, models, and practices. To improve means “to raise to a better quality or condition; make better” (Agnes, 2006, 718). The improvement realms of positive change, attaining expertise, developing excellent quality, and making things better is central to HRD. This core goal of improvement is possibly the single-most important idea in the profession and the core motivator of HRD professionals.

The HRD profession focuses on making things better and creating an improved future state. Examples include everything from helping individuals learn new content to helping organizational systems determine their strategic direction. There has been a continuing debate among HRD professionals as to the purpose of HRD being either learning or performance. For example, Krempl and Pace (2001, 55) contend that HRD “goals should clearly link to business outcomes,” while Bierema (1996, 24) states that “valuing development only if it contributes to productivity is a point of view that has perpetuated the mechanistic model of the past three hundred years.” It is interesting to listen more closely to each side and to discover that learning is seen as an avenue to performance and that performance requires learning (Ruona, 2000). In both cases, there is the overarching concern for improvement.

PROBLEM-SOLVING ORIENTATION

HRD is oriented to solutions—to solving problems. A problem can be thought of as “a question, matter, situation, or person that is perplexing or difficult” (Agnes, 2006, 1144). It is these perplexing or difficult situations, matters, and people that most often justify HRD and ignite the HRD process. Even though HRD professionals see themselves as constructive and positive agents, some do not want to talk about their work in the language of problems. Essentially, their view is that there is a present state and a future desirable state and the gap between is the opportunity or problem to be solved (Chermack, 2011, 2021).

At times, HRD professionals know more about the present state than the desired future state. At other times, they know more about the desired future state than the actual present state. HRD critics often say that HRD practitioners falsely know more about what should be done than they know about either the present or desired states. Other critics might say that some HRD people are more interested in their pet programs and activities than in the requirements of their host organization. These criticisms can be summarized as “having a solution in search of a problem” and “a program with no evidence of results.”

With all the various models and tools reported in the HRD literature, each with its own jargon, it is useful to think generally about HRD as a problem-defining and problem-solving process. HRD professionals have numerous strategies for defining problems and even more strategies for going about solving them. A core idea within HRD is to think of it being focused on solving problems for the purpose of improvement.

SYSTEMS THINKING

HRD professionals talk about system views and systems thinking. They think this way about themselves and the host organizations they serve. Systems thinking is basic to HRD theory and practice. Systems thinking is described as “a conceptual framework, a body of knowledge and tools that have been developed over the past fifty years, to make full patterns clearer, and to help us see how to change them effectively” (Senge, 1990, 7). Systems thinking is an outgrowth of systems theory. General systems theory was first described by Boulding (1956a) and von Bertalanffy (1962) with a clear antimechanistic view of the world and the full acknowledgment that all systems are ultimately open systems—not closed systems.

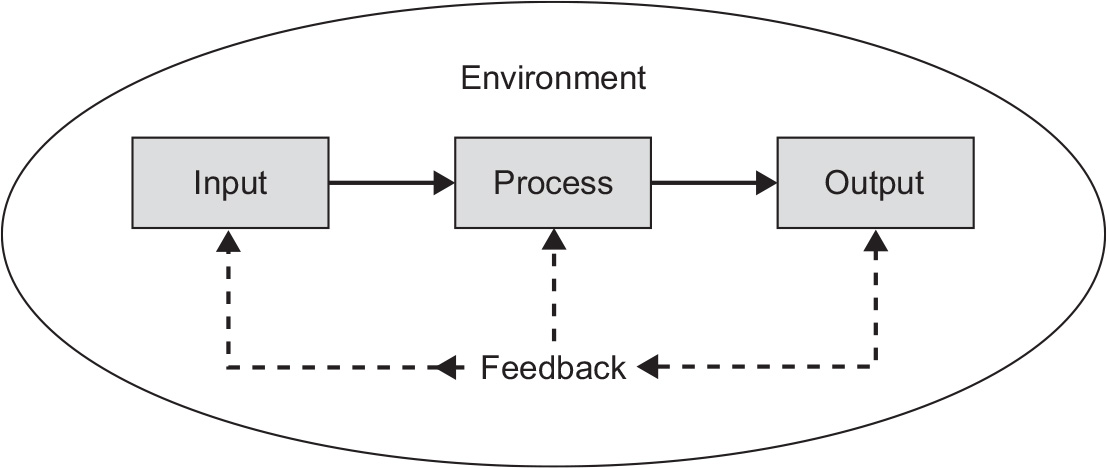

Figure 2.1: Basic Systems Model

The basic systems theory model includes inputs, processes, and outputs of a system as well as a feedback loop. Furthermore, basic systems theory acknowledges that a system is influenced by its larger surrounding system or environment (see figure 2.1) and that systems are not to be thought of as isolated and linear.

This informed view is referred to as an open system or a system that is capable of being influenced by forces external to the system under focus. These ideas provide the basis for many practical HRD tools for viewing improvement problems (opportunities) and for taking action.

Systems thinking allows HRD to view itself as a system and to view its host, or sponsoring organization, as a system. When HRD professionals speak about HRD as a system, they generally think of HRD as being a subsystem within a larger organizational system. Analysis experts sometimes refer to subsystems as processes. Thus, HRD is more often discussed as a process than a system. This is not meant to be confusing—most people simply acknowledge that a systems view and a process view are almost the same. It can be said, however, that when people talk about a systems view, they are usually thinking more broadly and more generally than when they are talking about a process view. There is a point when the system and process views overlap.

Basic systems theory—the root of systems thinking—informs us that there are initial and fundamental requirements for engaging in systems thinking and analysis about systems (and processes). Just being able to answer and gain consensus on the following three questions is enough systems thinking for most HRD practitioners.

1. What is the name and purpose of the system? What systems are called, and what their purposes may be, are often points of misunderstanding from one person to another. By naming the system, people can first agree as to what system they are talking about. It is very interesting to have intelligent and experienced people in a room begin to talk about a situation only to find out that the unnamed system some are talking about differs from the system others are talking about. Furthermore, differing perspectives on the purpose of the system are almost always under contention until made explicit.

2. What are the parts or elements of the system? This question throws another elementary but essential challenge to a systems thinker. We find that people with a singular or limited worldview only see the world through that lens. Examples we have seen include production people not seeing the customer; sales people not seeing production; new technology people only seeing technology itself as the system rather than the larger system of people, processes, and outputs; and legal people seeing the system as conflictive by nature rather than harmonious. With these limited views, individuals will be drawn to varying perceptions of the parts or elements of the system that may not match reality.

3. What are the relationships between the parts? Here is the real magic of systems theory—analyzing the relationships between the parts and the impacts of those relationships. Even HRD experts wonder if they ever get it complete. Indeed, good analysts are the first to admit their own shortcomings. Yet, their belief is that in the struggle to understand a system, an analyst ends up with a better and more complete understanding of that system. Studying the relationship between parts forces analysts to dive deeper into understanding and explaining a system—why it works and why it is not working. A simple example to illustrate this point is when enormous pressure is put on an employee only to find out if he or she can, in fact, perform a task. If the person can then perform the task, expertise is not the missing piece. Thus, the idea that people are not performing tasks well and need training is unacceptable until more is known. Workers may know how to perform the task well but are unable to, or choose not to, for many reasons. You probably could name several from your own experience. There are numerous reasons in any system why things happen and do not happen. Figuring these out requires more than superficial analysis or metaphoric analogies. Systems theory is basic.

HRD Worldviews

The good news is that HRD professionals almost always have a worldview. The bad news is that they rarely articulate it and systematically operationalize it for themselves, their colleagues, and their clients. Years ago, Zemke and Kerlinger (1982, 17–25) implored HRD professionals to have general mental models for the purpose of being able to figure out the complexity and context surrounding HRD work.

HRD AND ITS ENVIRONMENT

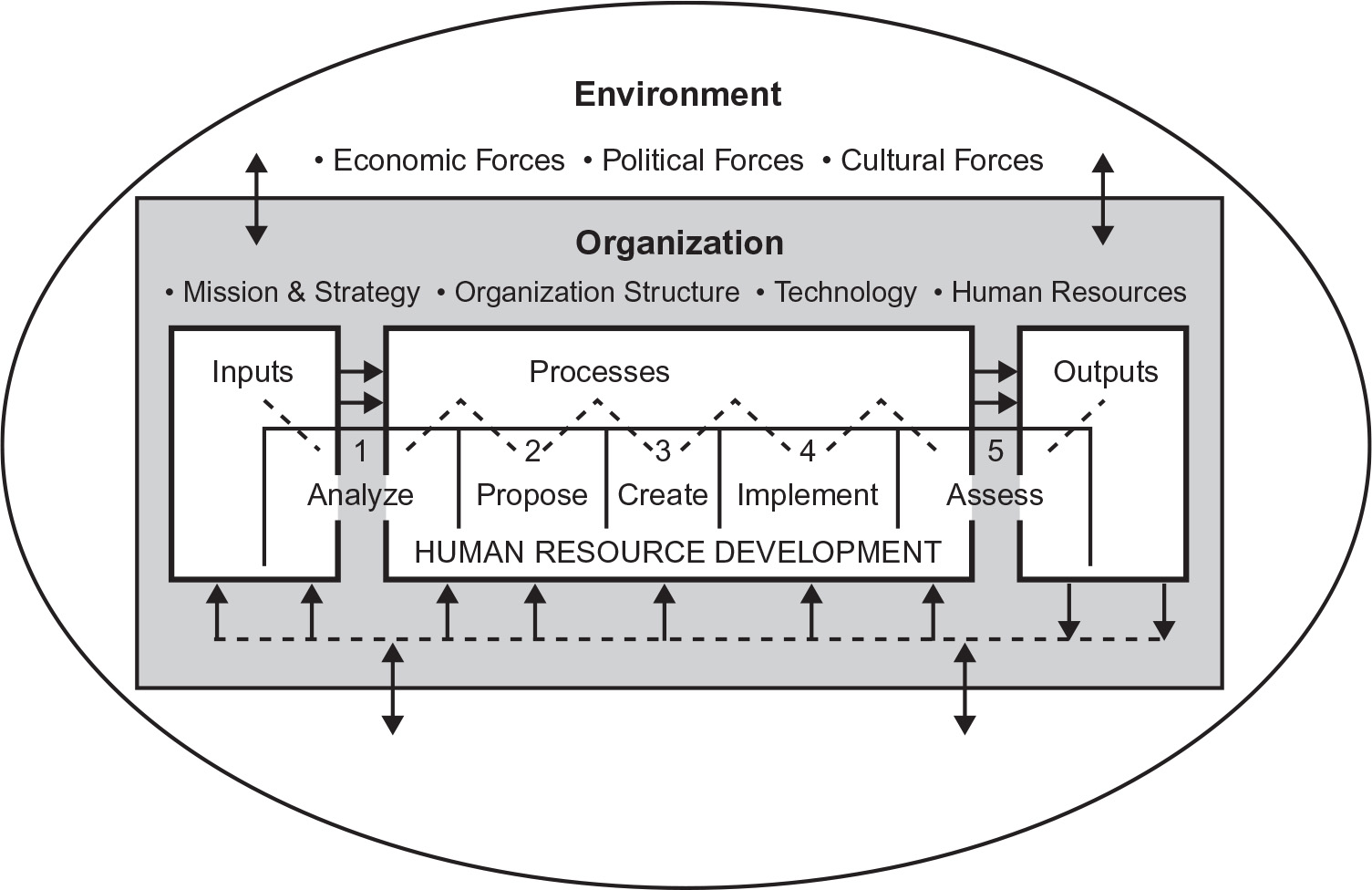

Figure 2.2 contains a worldview generally useful to the purpose and context of HRD. This contextual model positions HRD as a five-phase process (system) paralleling and connecting with the other processes in the host system or organization. The organizational system and subprocesses each have their inputs, work processes, and outputs. The environment where the organizational system functions is also identified and illustrated. The organizational system is seen to have its unique mission and strategy, organization structure, technology, and human resources. Its economic, political, and cultural forces characterize the larger environment. As expected, this is an open system where influence of any component can slide up and down the levels of this model. For example, powerful global economy influences can push down the need and nature of an executive development program sponsored by the HRD department in a specific company. Those external influences could dictate other changes such as location of manufacturing and marketing methods.

Figure 2.2: Five Phase Human Resource Development in Context of the Organization and Environment

Source: Swanson, 2001c, 305.

LEARNER PERSPECTIVE

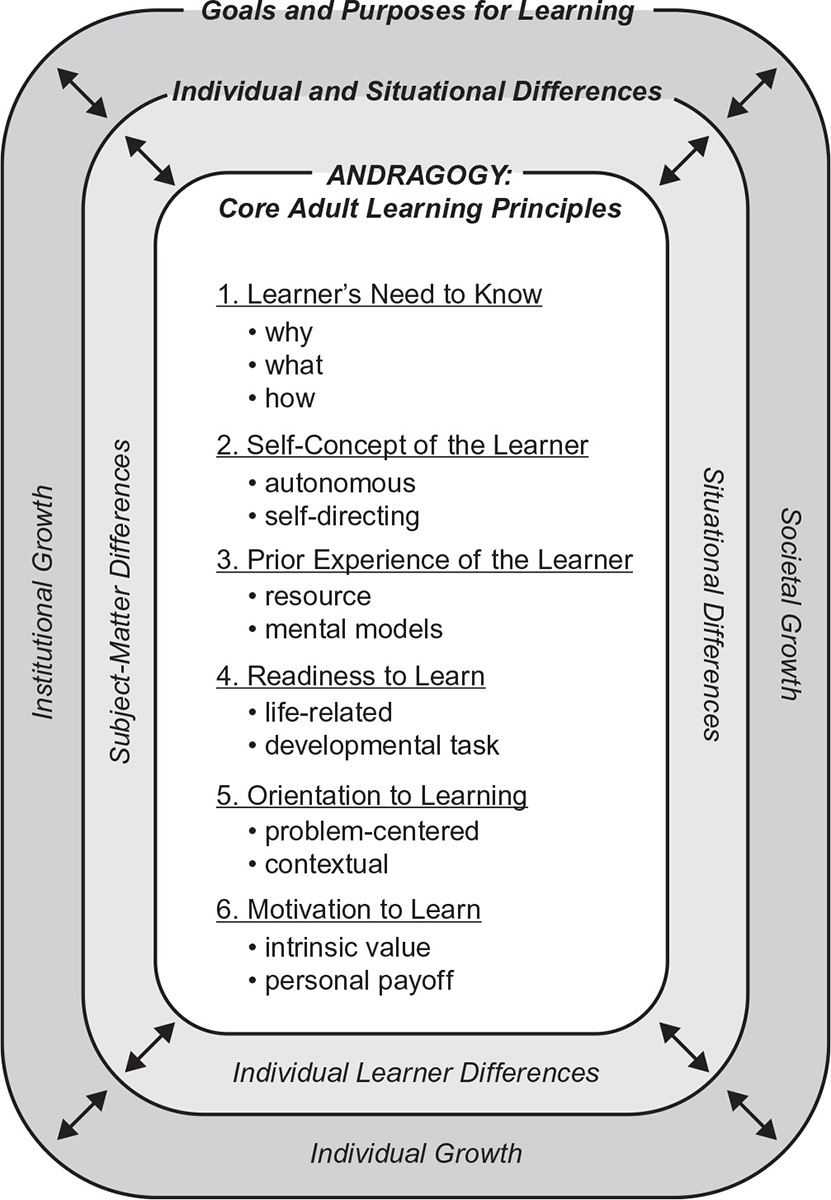

Patricia McLagan (2017), HRD thought leader, presents a case of self-managed learning being a necessary and exciting upgrade that will keep you in charge of, rather than becoming a servant to, increasingly intelligent technologies. Other learner worldviews that gain support in HRD include involving individuals as leaders, learners, and contributors. Figure 2.3 stems from the original work of Malcolm Knowles, considered in the United States to be the father of adult learning or andragogy. The perspective of andragogy in practice places adult learning principles into the context of adult life through the perspectives of (1) the goals and purposes for learning, and (2) individual and situational differences. In figure 2.3 you see the six adult learning principles enveloped by the contextual purpose and situational issues that impact learning and development. The HRD worldview related to the adult learner is concerned with the learning process as it takes place within the context of the learning purpose and situation (Knowles, Holton, and Swanson, 2005).

Figure 2.3: Andragogy in Practice

Source: Knowles, Holton, and Swanson, 2005, 4.

ORGANIZATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

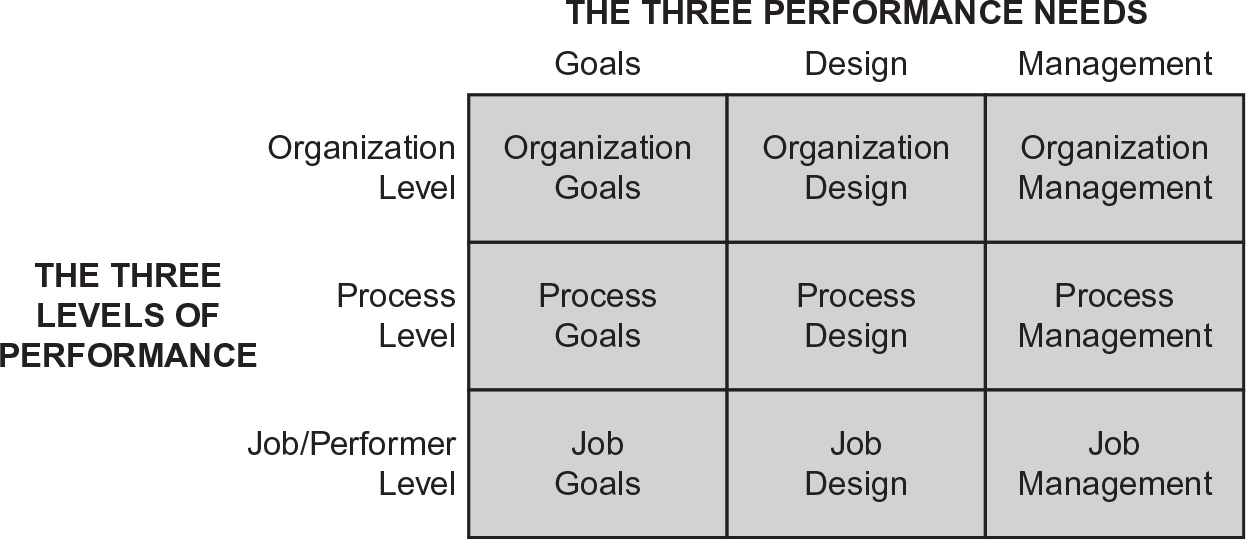

The organizational worldview perspective is presented here by the work of Rummler and Brache (2012). They offer a perspective on the organizational variables that explain organizational performance. In their matrix of nine performance variables, the dominance of the organization and its need to perform is acknowledged (see figure 2.4). Included are three performance levels—organization, work process, and individual contributor—and three performance needs—goals, design, and management. This worldview argues for the organization that reaches to the individual, while the earlier learner perspective has the individual dominating and reaching to the organization. The organization performance view takes the general stance that good people may be working in bad systems. For example, the quality improvement expert, W. Edwards Deming, estimated that 90 percent of the problems that might be blamed on individuals in the workplace are a result of having them working in bad processes or systems. He fundamentally believed in human beings and their capacity to learn and perform. His goal was to focus on the system structure and processes that stood in the way of learning and performance.

GLOBAL CONTEXT

Adam Smith, a Scottish philosopher and political economist, was the author of the 1776 book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. His treatise spurs continuing interpretations of the socio-technical-economic systems that provoke scholars and decision makers even to the present day. His commitment was to capitalistic free markets and how rational self-interest and competition can lead to common well-being that is regularly challenged (Friedman, 2021).

Figure 2.4: Nine Performance Variables

Source: Rummler and Brache, 1995, 8. Used with permission.

In stark contrast, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1887), the work of Karl Marx, Prussian philosopher and political economist, also continues to provoke scholars and decision makers. Marx argued that capitalism leads to class struggles that will result in destruction and the ultimate rise of communism.

The historical context in which Smith and Marx advanced their theories has greatly changed, but most would argue that the motivation of human beings has not changed. Global political, economic, and cultural forces have radically shifted in the twenty-first century and will continue to change. In the past, these factors that were on the outer rim of concerns for most HRD professionals—those things that happened in faraway nations—are now a part of standard organizational considerations. To its credit, HRD has had a long tradition of cultural sensitivity, as it has worked from region to region nationally and from one work group to another. Easing into multinational people interaction issues has been relatively painless for the HRD profession, and there has been high demand for HRD expertise in aiding individuals to function in the globalization process.

McLean and McLean (2001) have hypothesized that HRD is an important factor in the inevitable move to globalization. They note that while globalization is not new, its present demands are so intense that it fundamentally changes the way and rate at which change occurs. Globalization “enables the world to reach into individuals, corporations, and nation-states farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper than ever before” (Friedman, 2000, 9). A framework for HRD to use in dealing with day-to-day globalization issues is to adopt the following new mind-sets (Rhinesmith, 1995):

• Gather global trends on learning related technology, training, and organization development to improve the competitive edge.

• Think and work through contradictory needs resulting from paradoxes and confrontations in a complex global world.

• View the organization as a process rather than a structure.

• Increase ability to work with people having various abilities, experiences, and cultures.

• Manage continuous change and uncertainty.

• Seek lifelong learning and organizational improvement on numerous fronts.

It is important to note that these mindsets are inadequate in resolving the larger social-economic-political struggle between political economies—Smith, Marx, and those in between—when thinking about humaneness, system viability, and meaningful participation in rival systems.

The overall message in presenting these several worldviews is that every HRD professional should have a worldview that allows her/him to think through situations time and time again. Conceptual worldview models help HRD professionals gain clarity of the complex situations they face.

Thus far we have discussed core ideas that influence HRD. Each of these basic ideas assists in understanding the challenges HRD faces and the strategies it takes in facing those challenges. The ideas include the following:

• Belief in human potential

• Improvement as a goal

• Problem-solving orientation

• Systems thinking

• Worldviews

• Global context

HRD Process

Based on the ideas in the prior sections, it is rational to think of HRD as a purposeful process or system. The position taken here is that the dominant view of HRD should be that of a process. The views of HRD as a function, department, and job are the less important contextual variations.

When HRD is viewed as a process and is thought of in terms of input, process, output, and feedback within a dynamic environment, potential contributors and partners will not be excluded. In that HRD needs to engage others in the organizational system to support and carry out portions of HRD work, it is best to have the process view as the dominant view.

Most often HRD is discussed as a process and not a system. Furthermore, the process elements are most commonly called process phases instead of elements or steps.

PROCESS PHASES OF HRD

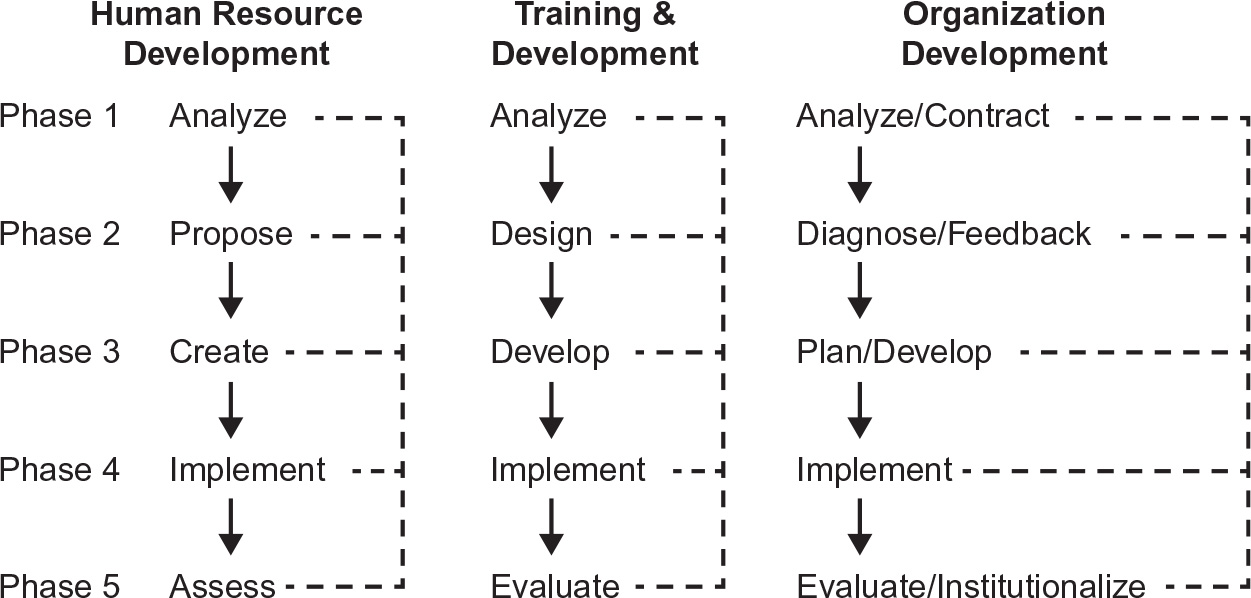

HRD has been defined in this text as a five-phase process that is essentially a problem-defining and problem-solving method. HRD and its two primary components—training and development (T&D) and organization development (OD)—are each five-phase processes. Wording for the general process phases of HRD, T&D, and OD have a common thread with slightly varying terminology.

INTERPLAY BETWEEN THE PHASES OF THE HRD PROCESS

The process phase view suggests that there are major stages in the HRD process and that each phase has an important relationship crucial to achieving the desired outcomes. One of the biggest professional problems facing HRD practitioners is in honoring all phases. Studies of HRD practice reveal shortcomings at the analysis and assessment/evaluation phases. These are the two most strategic phases of the HRD process. The shortcomings are compounded because relationships between the middle phases rely on the analysis for direction and substance. Furthermore, organizational commitment to HRD is dependent on positive performance results reported at the assessment/evaluation phase (Kusy, 1988; Mattson, 2001, Phillips and Phillips, 2016).

Threats to Excellent Practice

Davis and Davis (1998) tell us that, “The HRD movement, on its way to becoming a serious profession, can no longer afford an atheoretical approach” (41). Even with maturation, there are serious threats to theoretically sound and systematic HRD. Three of those threats are discussed here briefly.

TURNING THE HRD INTERVENTION INTO A FUN EVENT

The actual time that people get together within the HRD process can become the focal point, with the real reason for getting together being lost. This is an ever-present threat to a systematic approach to HRD. Obsessions with fun-filled events and hearing everyone’s full opinion on a matter can become an end unto itself rather than a means to an end. An irrational concern for participant satisfaction can also fuel the possibility of undermining the process.

THE RATE OF CHANGE

The familiar saying, “The faster I go, the behinder I get,” haunts most HRD practitioners. The intensity of the rate of change requires more from HRD, which then can serve to undermine a systematic HRD process. Not enough time? It is very tempting to eliminate or cut back on the up-front analysis and go with the off-the-top-of-your-head analysis or to bypass the final assessment phase. The demand for speedy interventions is always a challenge and threat to high quality HRD.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE KEY PLAYERS

There are strengths and liabilities of three critically important key players in impacting HRD: (1) the HRD professional/analyst, (2) the client/decision maker, and (3) the host organization (Sleezer, 1991). Examples include an analyst overly focused on human relationships may ignore hard organizational system-level performance data; a client/decision maker can be guilty of not being able to see the forest because of the trees; and host organizations can have such deeply im-bedded norms and values that they interfere with opportunities for change. When the characteristics of the key players are ignored and not managed properly, the integrity of the HRD process will likely erode. Responsibly engaging multiple stakeholders and multiple sources of data in the HRD process is essential to good practice and requires careful attention. These characteristics influence the thoroughness and integrity of the overall process. When they are ignored, the integrity of the process can seriously erode.

Ethics and Integrity Standards

Human Resource Development (HRD) as a profession and a discipline is focused on training and development and organization development programs, along with career development, quality improvement, change efforts, and complimentary human resource management practices to advance the performance of individuals, teams, work processes, organizations, communities, and society.

HRD professionals are engaged in practice, research, consulting, and instruction/facilitation/teaching. Ideally they strive to create a body of research-based knowledge and expertise and apply it to HRD in various organizational, community, and societal settings while functioning as professors, researchers, organization development consultants, administrators, trainers, managers, and leaders. In process, HRD and its host organizations are concerned about ethical practices (Krause and Voss, 2007).

The Academy of Human Resource Development (AHRD) has produced Standards on Ethics and Integrity, 2nd edition (AHRD, 2018) to provide guidance for HRD professionals engaged in practice, research, consulting, and instruction/facilitation/teaching. Although these principles are aspiring in nature, they provide standards of conduct and set forth a common set of values. Adherence to these standards furthers HRD as a profession. The primary goal of the AHRD standards is to manage more clearly the ethics of balancing among individuals, groups, organizations, communities, and societies whenever conflicting needs arise. Case studies connected to the ethics and integrity standards have also been produced to assist in the interpretation of the standards (Aragon and Hatcher, 2001).

To ensure this balance, these standards identify a common set of values upon which HRD professionals build their professional and research work. In addition, the standards clarify both the general principles and the decision rules that cover most situations encountered by HRD professionals. They have as their primary goal the welfare and protection of the individuals, groups, and organizations with whom HRD professionals work.

Adherence to a dynamic set of standards for a professional’s work-related conduct requires a personal commitment to the lifelong effort to act ethically; to encourage ethical behavior by students, supervisors, employees, and colleagues as appropriate; and to consult with others, as needed, concerning ethical problems. It is the individual responsibility of each professional to aspire to the highest possible standards of conduct. Such professionals respect and protect human and civil rights and do not knowingly participate in or condone unfair discriminatory practices.

In providing both the universal principles and limited decision rules to cover the many situations encountered by HRD professionals, this document is intended to be generic and is not intended to be a comprehensive, problem-solving, or procedural document. Each professional’s personal experience as well as his or her individual and cultural values should be used to interpret, apply, and supplement the principles and rules set forth.

STANDARDS

An abbreviated content outline for the “HRD Ethics and Integrity Standards,” 2nd edition follows. A full standards document is available on the AHRD website (https://www.ahrd.org).

• General principles

• General standards

• Research and evaluation

• Advertising and other public statements

• Publication of work

• Privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality

• Teaching and facilitating

• Resolution of ethical issues and violations

Conclusion

To be effective over time, it is essential to have a worldview model for thinking about how HRD fits into the milieu of an organization and society. It is also essential to have a process view of how HRD works and connects with other processes. Taking the five-phase process view of HRD, the HRD profession has traditionally been stronger in the middle phases (creation and implementation) and has been working hard to master the analysis and assessment phases at each end of the process. In pursuit of problems, improvements, and systematic practice, HRD professionals struggle to maintain high standards of excellence, ethics, and integrity.

Reflection Questions

1. Is there a relationship among the improvement goal, problem-solving orientation, and systems thinking agreements within the HRD profession? Explain.

2. What about systems thinking in this chapter attracts you? What repels you?

3. What, if any, is the logical connection between the 2.1 and 2.2 graphic models in this chapter?

4. How does your general worldview fit with the HRD worldview (figure 2.2)?

5. Speculate how you think HRD gets into ethical binds?

Internet Resources. Instructional support materials for this chapter can be found on this website: www.texbookresources.net