9

Perspectives on Learning in Human Resource Development

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Learning Models at the Individual Level

• Andragogy: The Adult Learning Perspective

• Informal and Incidental Workplace Learning

Learning Models at the Organizational Level

• Learning Organization Strategy

Introduction

Learning is at the heart of Human Resource Development (HRD) and continues to be a core part of all paradigms of HRD. Whatever the debates about paradigms, nobody has ever suggested that HRD not embrace learning as foundational for the discipline. This chapter takes a closer look at representative theories and research on learning in HRD. First, core theories of learning are discussed. Then, representative learning models at the individual and organizational levels are reviewed. The purpose of this chapter is to provide key foundational perspectives on learning.

Theories of Learning

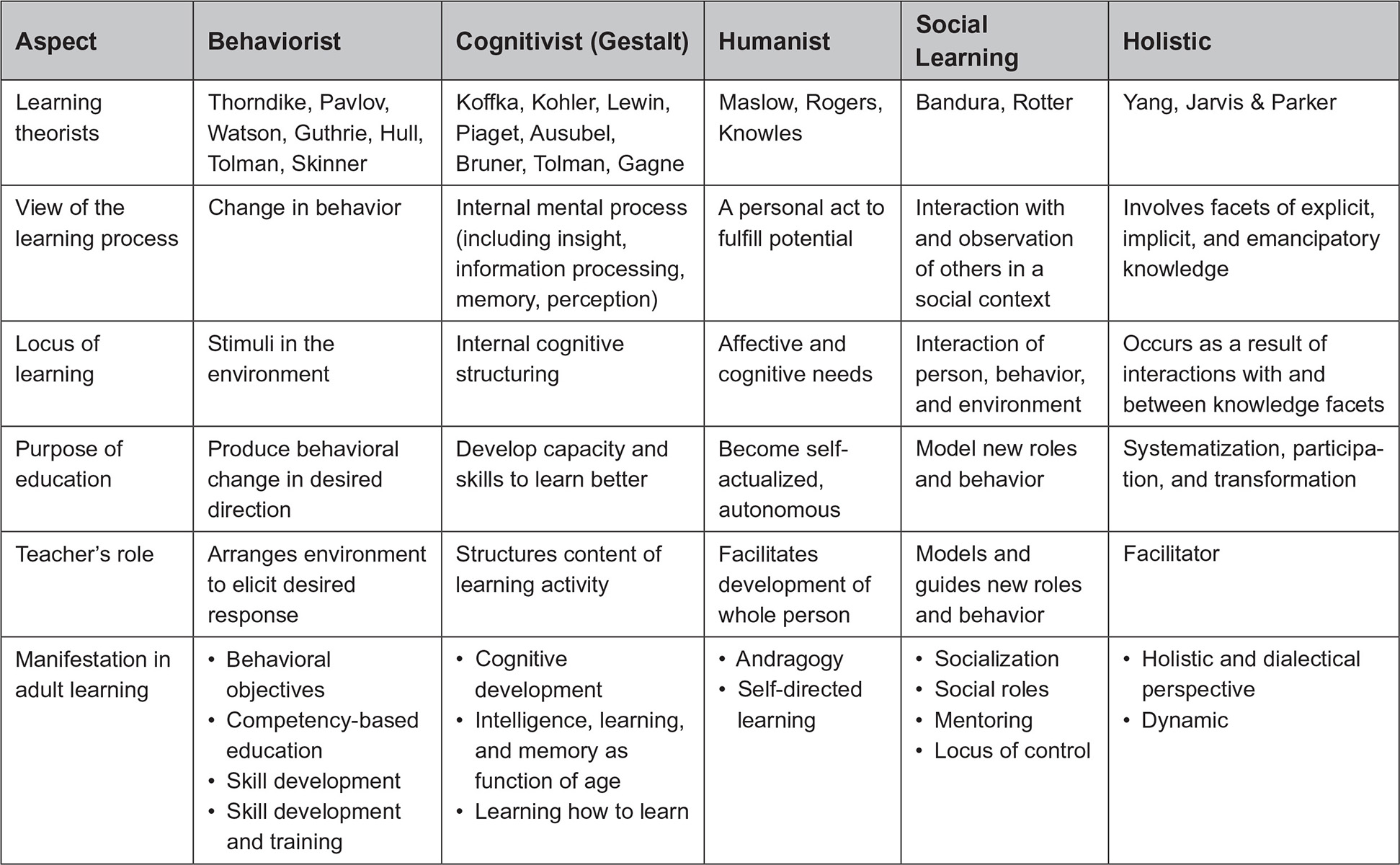

A summary of fundamental theories of learning including behaviorism, cognitivism, humanism, social learning, and holistic learning, are presented in figure 9.1. These are theoretical perspectives that can apply to learning in all settings, for all age groups, and for all types of learning events. In this section, each theory is described along with its primary contribution to HRD. Each has been the subject of extensive experience, thinking, writing, and research.

Figure 9.1 helps to show that each approach represents a fundamentally different view of learning. Each would define learning differently, prescribe different roles for the instructor, and seek different outcomes from learning. Each has made a substantial contribution to learning and will continue to inform HRD practice. This section provides only a summary of each. Readers interested in a more thorough presentation are encouraged to consult Ormond (1999); Hergen-hahn and Olson (1993); or Merriam, Caffarella, and Baumgartner (2006).

Very few HRD professionals or HRD interventions use only one of these metatheories. Most are pretty eclectic, using a combination of approaches that fit the particular situation. Thus, these five approaches should not be read as either/or choices but instead as five different methods to be drawn upon as appropriate to one’s particular needs. They are presented here in their pure form to enhance the understanding of each. However, in practice, they are usually adapted and blended to accomplish specific objectives. The challenge for the HRD professional is to understand them and make sound judgments about which approach to use in a given situation. It is crucial not to reject any single theory, for each has its strengths and weaknesses.

BEHAVIORISM

Behaviorists are primarily concerned with changes in behavior as a result of learning. Behaviorism has a long and rich history, initially developed by John B. Watson, who introduced the term in 1913 and developed it in the early twentieth century (Ormond, 1999). Six prominent learning theorists are most commonly included in this school: Ivan Pavlov, Edward L. Thorndike, John B. Watson, Edwin R. Guthrie, Clark L. Hull, and B. F. Skinner. Pavlov and Skinner are the best-known contributors, with Pavlov having developed the classical conditioning model and Skinner the operant conditioning model. While each of these six scholars had different views of behaviorism, Ormond (1999) identified seven core assumptions that they share:

Figure 9.1: Orientations to Learning

Source: Adapted from Merriam and Caffarella, 2006, 264.

1. Principles of learning apply equally to different behaviors and different species of animals.

2. Learning processes can be studied most objectively when the focus of the study is on stimulus and response.

3. Internal cognitive processes are largely excluded from scientific study.

4. Learning involves a behavior change.

5. Organisms are born as blank slates.

6. Learning is primarily the result of environmental events.

7. The most useful theories tend to be parsimonious ones.

Behaviorists put primary emphasis on how the external environment influences a person’s behavior and learning. Rewards and incentives play a crucial role in building motivation to learn. In classic behaviorism, the role of the learning facilitator is to structure the environment to elicit the desired response from the learner.

Behaviorism has played a central role in HRD. Its key contributions include the following:

• Focus on behavior. The focus on behavior is important because performance change does not occur without changing Behavior. Although behavior change alone without internal cognitive changes is usually not desirable, neither is cognitive change alone. Thus, behaviorism has led to popular practices, such as behavioral objectives and competency-based education.

• Focus on the environment. Behaviorism reminds us of the central role that the external environment plays in shaping human learning and performance. Individuals in an organization are subjected to several factors (e.g., rewards and incentives, supports, etc.) that will influence their performance. As discussed in chapter 6, behaviorism provides the link between psychology and economics in HRD.

• Foundation for transfer of learning. Behaviorism also provides part of the foundation for transfer of learning research. Transfer of learning is concerned with how the environment impacts the use of learning on the job. Transfer research (e.g., Rouillier and Goldstein, 1993) shows that the environment is at least as necessary, if not more so, than learning in predicting the use of learning on the job.

• Foundation for expertise development training. As indicated in figure 9.1, behaviorism has provided much of the foundation for skill or competency-oriented training and development. Behavioral objectives are another contribution from behaviorists.

Behaviorism has also been heavily criticized, primarily by adult educators who prefer a more humanistic and constructivist perspective. The chief criticism is that behaviorism views the learner as passive and dependent. In addition, behaviorism does not account for the role of personal insight and meaning in learning. These are legitimate criticisms and explain why behaviorism is rarely the only learning theory employed. On the other hand, there are training interventions that are appropriately taught in a behavioral approach. For example, training police officers on how to respond when attacked is an appropriate use of behavioral methods because officers have to react instinctively.

Behavioristic interventions are also objectionable to some HRD professionals because they find them offensive at a values level. This is particularly true of those who favor an adult learning perspective that resists external control over a person’s learning process (McLagan, 2017). Most HRD professionals believe that there are legitimate uses of behaviorism when the situation warrants this type of learning. We question the objections about training, such as in the police example or in cases where certification of skills externally mandated is essential for safety. For example, airplane pilots, chemical plant operators, surgeons, and nuclear plant operators must pass rigorous certification programs that are behavioristic that few of us would want to be changed.

COGNITIVISM (GESTALT)

Gestalt psychology (cognitivism) arose as a direct response to the limits of behaviorism, particularly the absence of meaningfulness in human learning. The early roots can be traced back to the 1920s and 1930s through Edward Tolman, the Gestalt psychologists of Germany, Jean Piaget, and Lev Vygotsky (Ormond 1999). However, more contemporary cognitivism began to appear in the 1950s and 1960s. Ormond (1999) identifies seven core assumptions of contemporary cognitivism:

1. Some learning processes may be unique to human beings.

2. Cognitive processes are the focus of study.

3. Objective, systematic observations of people’s behavior should focus on scientific inquiry; however, inferences about unobservable mental processes can often be drawn from such behavior.

4. Individuals are actively involved in the learning process.

5. Learning involves the formation of mental associations that are not necessarily reflected in overt behavior changes.

6. Knowledge is organized.

7. Learning is a process of relating new information to previously learned information.

Cognitivists are primarily concerned with insight and understanding. They see people not as passive and shaped by their environment but instead as capable of actively shaping the environment themselves. Furthermore, cognitivists focus on the internal process of acquiring, understanding, and retaining learning. Because of this, they suggest that the focus of the learning facilitator should be on structuring the content and the learning activity so learners can acquire information optimally.

Gestalt theory is the first form of cognitivist theory. Some well-known names within HRD fit under this umbrella, including Kurt Lewin (organization development), Jean Piaget (cognitive development), and Jerome Bruner (discovery learning). Cognitivism has made significant contributions to HRD and adult learning. Some key ones include the following:

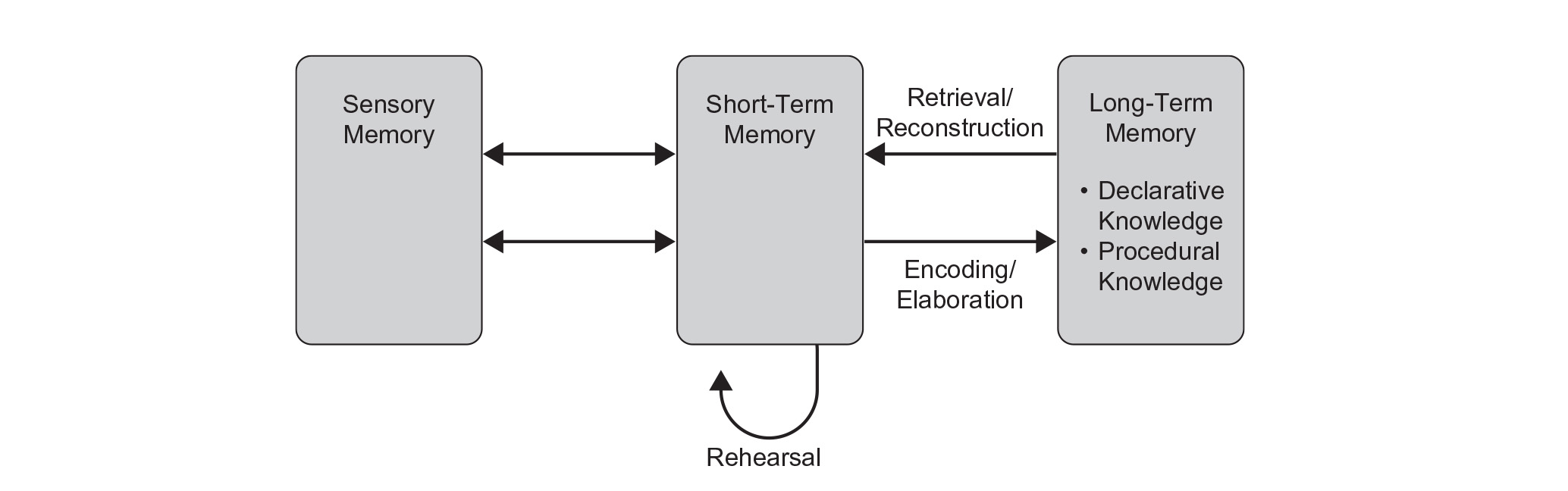

Figure 9.2: The Information-Processing Model

Source: Bruning, Schraw, and Ronning, 1999, 16. Used with permission.

• Information processing. Central to cognitivism is the concept of the human mind as an information processor. Figure 9.2 shows a basic schematic view of the human information-processing system. Notice that there are three key components: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Cognitivists are particularly concerned with the processes shown by arrows in this schematic. These arrows represent the mental processes of moving information from sensory memory to short-term memory, and from short-term memory to long-term memory, and retrieving information from long-term memory.

• Metacognition. Along with these basic information-processing components, cognitivism also focuses on how individuals control their cognitive processes, called metacognition. This concept is more commonly known in HRD and adult learning as “learning how to learn.”

• Cognitive development. Another significant contribution has been the focus on how cognition develops over the life span. It is now generally accepted that cognitive development continues throughout adulthood.

Cognitivism has not received the same degree of criticism that behaviorism has. While less dominant than behaviorism, cognitivism has made very important contributions in HRD and is widely utilized. It is seen in some circles as incomplete because it views the human mind as too abstract. Cognitivism has been the stimulant for more recent trends of brain research. Byrnes (2001) argues that several “trends have created an atmosphere of increased (though certainly not universal) acceptance of the idea that neuroscientific research could provide answers to important questions about learning and cognition. Most scholars believe that the available neuroscientific evidence is provocative and interesting, but far from conclusive” (2).

HUMANISM

Humanism did not emerge as a learning theory but rather a general approach to psychology. The work of Abraham Maslow (1968, 1970) and Carl Rogers (1961) provides the core of humanistic psychology. Buhler (1971), a leading humanistic psychologist (Lundin, 1991), identifies the core assumptions of humanism as follows:

• The person as a whole is the main subject of humanistic psychology.

• Humanistic psychology is concerned with the knowledge of a person’s entire life history.

• Human existence and intention are also of great importance.

• Life goals are of equal importance.

• Human creativity has a primary place.

• Humanistic psychology is frequently applied to psychotherapy.

Rogers (1980) puts forth his humanistic principles of learning by saying that such learning should have the following characteristics:

• Personal involvement: the affective and cognitive aspects must come from within.

• Self-initiated: a sense of discovery must come from within.

• Pervasive: learning makes a difference in the behavior, the attitudes, and perhaps even the personality of the learner.

• Evaluated by the learner: the learner can best determine whether the learning experience is meeting a need.

• Essence is meaning: when experiential learning occurs, its meaning to the learner becomes incorporated into the total experience.

Humanism adds yet another dimension to learning and has dominated much of adult learning. It is most concerned with development by the whole person, and it places a great deal of emphasis on the affective component of the learning process largely overlooked by other learning theories. The learning facilitator takes into account the whole person and their life situation in planning the learning experience. Humanists view individuals as seeking self-actualization through learning and of being capable of controlling their own learning process. Adult learning theories, particularly andragogy, best fit HRD. In addition, self-directed learning and much of career development are grounded in humanism.

In many respects, humanism is central to HRD. If humans are not viewed as motivated to develop and improve, then at least part of the core premise of HRD disappears. At the same time, humanism is also a source of debate within HRD because some view the performance paradigm as violating humanistic tenets. If a person believes completely in the humanistic view of learning, then allowing for behavioral components in the learning process is disconcerting. The strong preference here is to see them coexist.

SOCIAL LEARNING

Social learning focuses on how people learn by interacting with and observing other people. This type of learning focuses on the social context in which learning occurs. Some people view social learning as a special type of behaviorism because it reflects how individuals learn from people in their environment. Others view it as a separate metatheory because the learner is also actively making meaning of the interactions.

A foundational contribution of social learning is that people can learn vicariously by imitating others. Thus, central to social learning processes is that people learn from role models. This contradicts behaviorists who contend that learners need to perform themselves and be reinforced for learning to occur. The social learning facilitator models new behaviors and guides individuals in learning from others. Albert Bandura is probably the best-known name is this area. It was his works in the 1960s and extending through the 1980s that fully developed social learning theory.

Ormond (1999) lists four core assumptions of social learning theory: people can learn by observing the behaviors of others and the outcomes of those behaviors; learning can occur without a change in behavior; the consequences of Behavior play a role in learning; cognition plays a role in learning.

Social learning also occupies an important place in HRD. One contribution is in classroom learning, where social learning focuses on the role of the facilitator as a model for behaviors to be learned. Facilitators often underestimate their influence as role models and forget to utilize role modeling as part of their instructional plan.

Social learning may make its biggest contribution through nonclassroom learning. One area is in new employee development, where socialization processes account for the largest portion of new employee development (Holton, 1996c; Holton and Russell, 1999; Korte, 2007). Socialization is how organizations pass on their culture to new employees and teach them how to be effective in the organization. It is an informal process that occurs through social interactions between new employees and organizational members. Another critical area is mentoring, a primary means of on-the-job development in many organizations. It is often used to develop new managers. This is a social learning process, as mentors teach and coach protégés. Yet another key area is on-the-job training, whereby newcomers learn their jobs from job incumbents, in part by direct instruction but also by observing the incumbent and using them as a role model.

There are few HRD critics of social learning, as it contributes to learning theory without inciting strong arguments. Social learning is widely accepted as an effective and vital learning process. Motivational training and change readiness are two important applications. When properly applied, it enhances education and contributes to learning that often cannot occur in the classroom.

HOLISTIC LEARNING

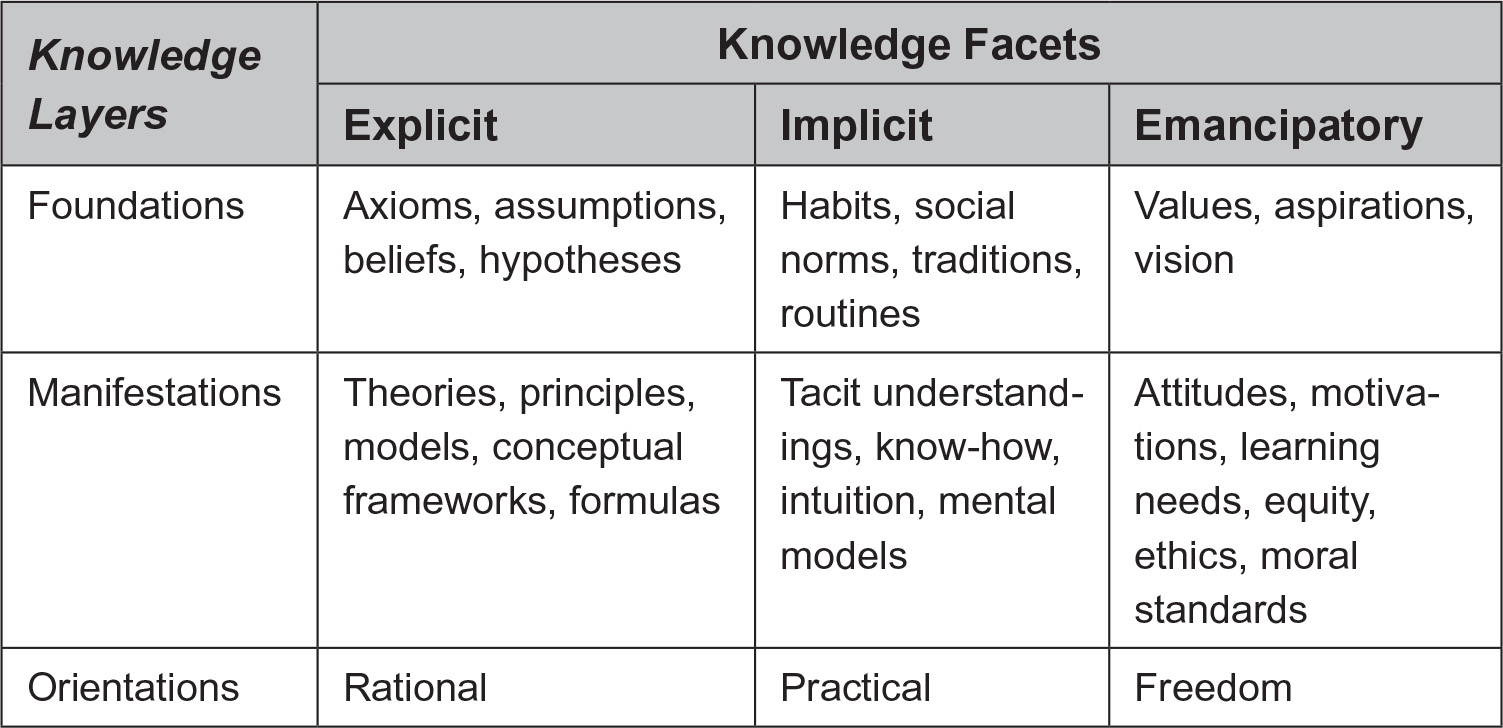

The Holistic Theory of Knowledge and Adult Learning has been advanced by Baiyin Yang (2003; 2004a; 2004b). His theory plays a unique role in integrating so many rival learning theories that distinguish themselves by their differences rather than their commonalities. Yang’s holistic theory conceptualizes knowledge into three indivisible facets—implicit, explicit, and emancipatory. Furthermore, each of these has three layers—foundation, manifestation, and orientation. The interactions between the facets and layers are shown in figure 9.3.

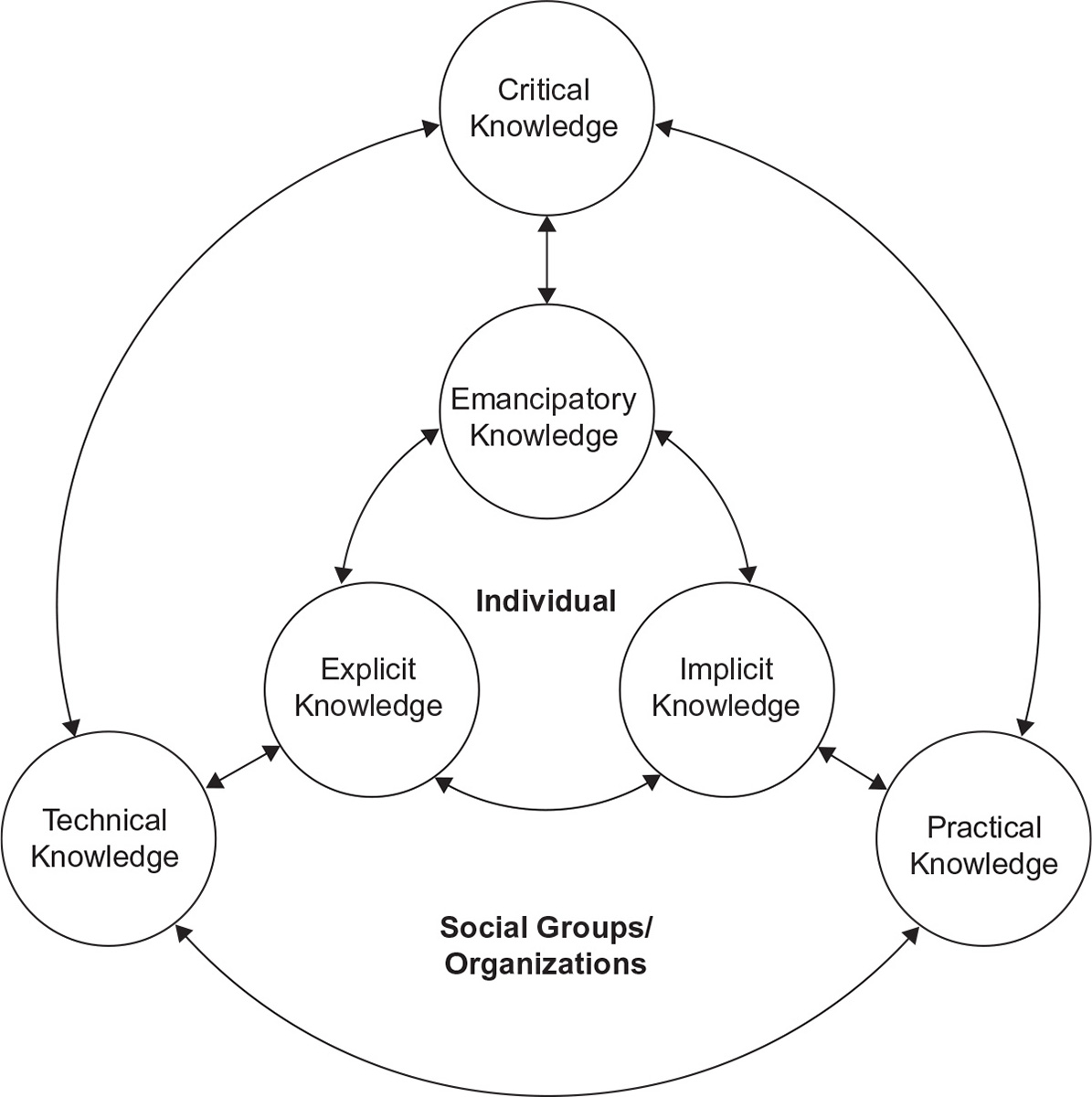

It is essential to note that most perspectives on learning are focused on the individual level. Holistic theory embraces the individual, group, and organizational learning challenges facing HRD. Figure 9.4 visually arranges the knowledge facets and knowledge layers in an individual and social group/organization relationship.

Another feature of the holistic theory is its attempt to harness the best of three major views on the nature of knowledge and learning put forth by Mezirow (1996). They include: (1) the empirical/analytic paradigm (objective interpretation), (2) the interpretist paradigm (subjective interpretation), and (3) the critical paradigm (power interpretation).

Figure 9.3: Holistic Theory of Knowledge and Learning: Indications of Three Knowledge Facts and Three Knowledge Layers

Source: Yang, 2003.

Figure 9.4: Holistic Theory of Knowledge and Learning: Dynamic Relationships between Individual, Organization, and Social/Cultural Contexts

Source: Yang, 2003.

The value of the holistic theory is in making connections between seemingly disparate streams of philosophy and research related to knowledge and learning (Jarvis and Parker, 2005; Nafukho, 2006). Critics would argue that such connections are tenuous.

Most learning theories can be embedded in one or a blend of the five general theories of learning that have been presented. Each general theory makes unique contributions and adds power to practice in HRD. Understanding each so that they can be employed in appropriate situations is important. Again, no single theory is best. In any given situation, one or a combination of approaches is likely to be most effective.

Learning Models at the Individual Level

In this section, models of learning are reviewed. First, andragogy is discussed as a core adult learning model that has played a central role in HRD. Also, the andragogy in practice model is presented as a more comprehensive elaboration of andragogy (Knowles et al., 2020; Holton, Swanson, and Naquin, 2001). Next, Kolb’s experiential learning model is considered, followed by informal and incidental learning. Transformational learning is discussed last.

ANDRAGOGY: THE ADULT LEARNING PERSPECTIVE

When Knowles introduced andragogy in the United States in the late 1960s, the idea broke new ground and sparked much subsequent research and controversy. Spurred in part by the need for a defining theory within the field of adult education, andragogy has been extensively analyzed and critiqued (Henschke, 1998). Andragogy has been alternately described as a set of guidelines (Merriam, 1993), a philosophy (Pratt, 1993), and a set of assumptions (Brookfield, 1986). Davenport and Davenport (1985) note that andragogy has been called a theory of adult learning, a method or technique of adult education, and a set of assumptions about adult learners. Regardless of how it is viewed, “it is an honest attempt to focus on the learner. In this sense, it does provide an alternative to the methodology-centered instructional design perspective” (Feur and Gerber, 1988, 144).

Brookfield (1986) asserts that andragogy is the “single most popular idea in the education and training of adults” (91). HRD and adult education professionals, particularly beginning ones, find them invaluable in shaping the learning process to be more effective with adults.

The Core Andragogical Model Popularized by Knowles (1970), the original andragogical model presents core principles of adult learning and important assumptions about adult learners. These core principles of adult learning enable those designing and conducting adult learning to create more effective learning processes for adults. The model is a transactional one (Brookfield, 1986) in that it speaks to the characteristics of the learning transaction. It applies to any adult learning transaction—from community education to human resource development in organizations.

The number of andragogical principles has grown from four to six over the years as Knowles refined his thinking (1989). The current six core assumptions or principles of andragogy are as follows (Knowles, Holton, Swanson, and Robinson, 2020):

1. Adults need to know why they need to learn something before learning it.

2. The self-concept of adults is heavily dependent on a move toward self-direction.

3. Prior experiences of the learner provide a rich resource for learning.

4. Adults typically become ready to learn when they experience a need to cope with a life situation or perform a task.

5. Adults’ orientation to learning is life-centered, and they see education as a process of developing increased competency levels to achieve their full potential.

6. The motivation for adult learners is internal rather than external.

These core principles provide a sound foundation for planning adult learning experiences. They offer a practical approach to adult learning.

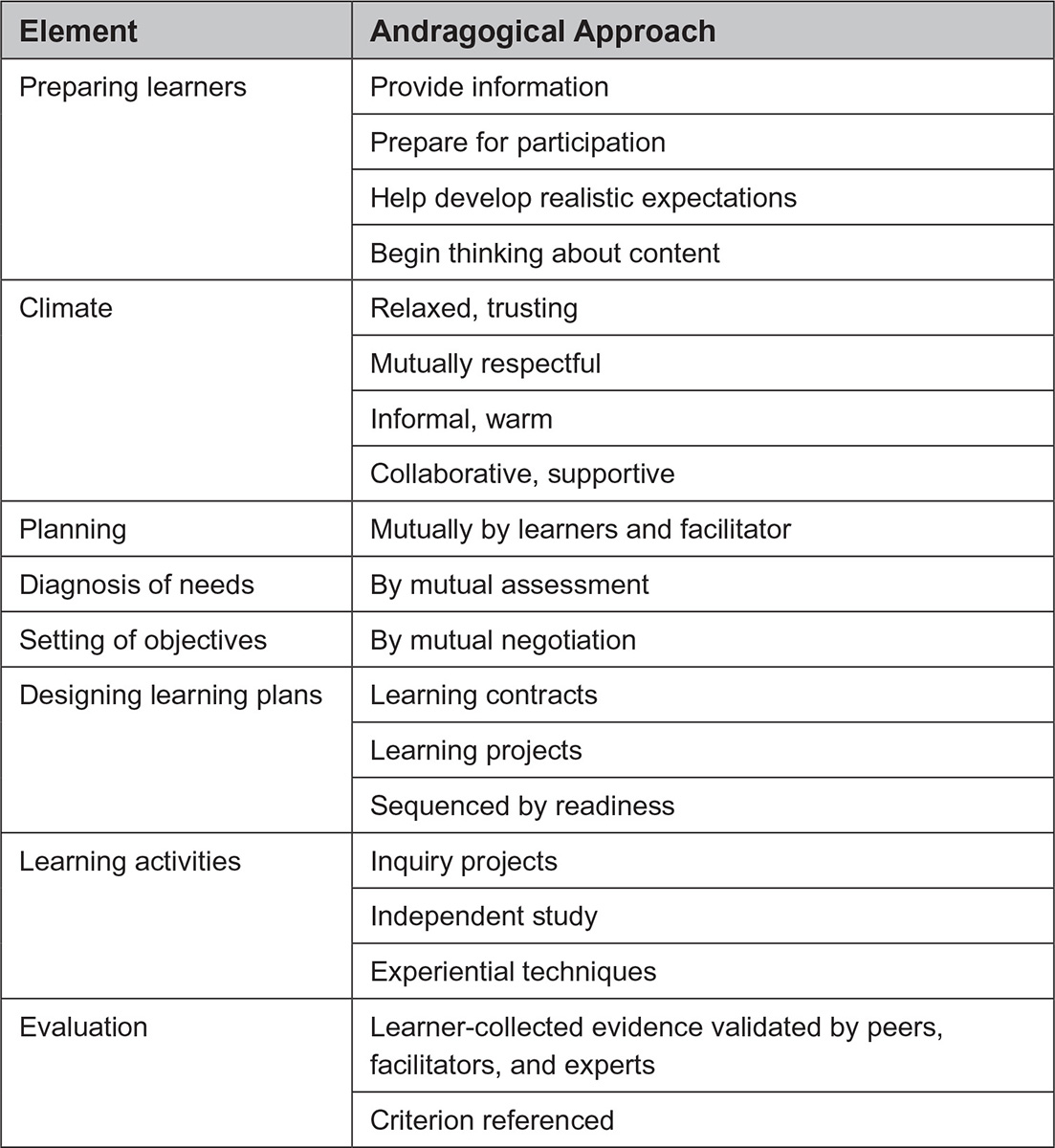

The second part of the andragogical model is called the andragogical process design steps for creating adult learning experiences (Knowles, 1984, 1995). The eight steps include: (1) preparing learners for the program, (2) establishing a climate conducive to learning, (3) involving learners in mutual planning, (4) involving participants in diagnosing their learning needs, (5) involving learners in forming their learning objectives, (6) involving learners in designing learning plans, (7) helping learners carry out their learning plans, and (8) involving learners in evaluating their learning outcomes. Figure 9.5 shows the andragogical process elements and andragogical approaches presented and updated by Knowles (1995).

Knowles (1984) noted that he had spent two decades experimenting with andragogy and had reached certain conclusions, including these:

• The andragogical model is a system of elements that can be adopted or adapted in whole or in part. It is not an ideology that must be applied totally and without modification. An essential feature of andragogy is flexibility.

• The appropriate starting point and strategies for applying the andragogical model depend on the situation. (418)

Figure 9.5: Process Design Steps of Andragogy

Source: Developed from Knowles, 1995.

Knowles confirmed through use that andragogy could be utilized in many different ways and would have to be adapted to fit individual situations. In reaction, the andragogical assumptions about adults have been criticized for appearing to claim to fit all situations or persons (Davenport, 1987; Davenport and Davenport, 1985; Day and Baskett, 1982; Elias, 1979; Hartree, 1984; Tennant, 1986).

ANDRAGOGY-IN-PRACTICE MODEL

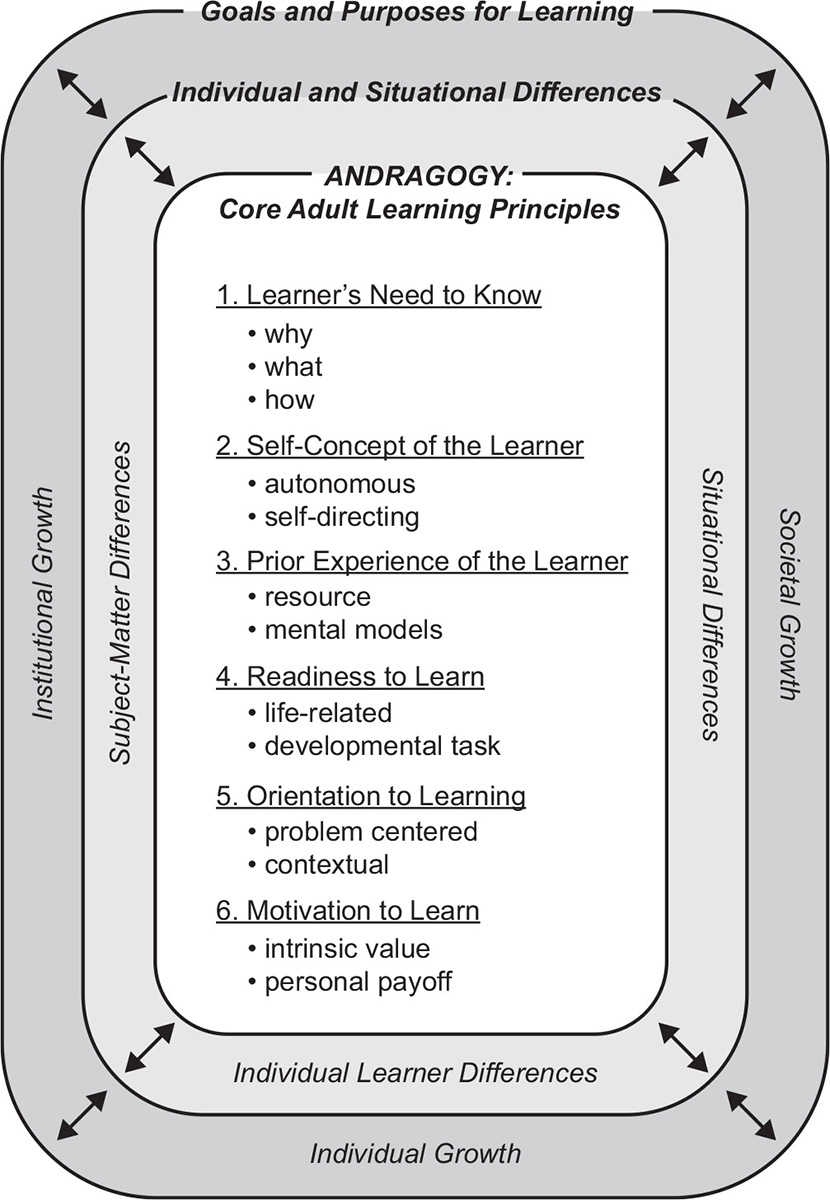

Andragogy in practice, the framework depicted in figure 9.6, is an enhanced conceptual framework to apply andragogy more systematically across multiple domains of adult learning practice (Knowles, Holton, Swanson, and Robinson, 2020). The three dimensions of andragogy in practice, shown as rings in the figure, are (1) goals and purposes for learning, (2) individual and situational differences, and (3) andragogy (core adult learning principles).

Figure 9.6: Andragogy in Practice Model

Source: Knowles, Holton, Swanson, and Robinson, 2020, 4.

In contrast to the original model of andragogy, this approach conceptually integrates the additional influences with the core adult learning principles. The three rings of the model interact, allowing the model to offer a three-dimensional process for adult learning situations. The result is a model that recognizes the lack of homogeneity among learners and learning situations and illustrates that the learning transaction is a multifaceted activity. This approach is entirely consistent with most of the program development literature in adult education that in some manner incorporates contextual analysis in developing programs (e.g., Houle, 1972; Knox, 1986a; Boone, 1985).

Goals and purposes for learning, the outer ring of the model, are portrayed as developmental outcomes. The goals and purposes of adult learning serve to shape and mold the learning experience. In this model, goals for adult learning events may fit into three general categories: individual, institutional, or societal (Knowles, 1970, 1980). Beder (1989) also used a similar approach to describe the purposes of adult education as facilitating change in society and supporting and maintaining good social order (societal), promoting productivity (institutional), and enhancing personal growth (individual).

Individual Growth The traditional view among most scholars and practitioners of adult learning is to think exclusively of individual growth. Representative researchers in this group might include some mentioned earlier, such as Mezirow (1991) and Brookfield (1984, 1987). Others advocate an individual development approach to workplace adult learning programs (Bierema, 1997; Dirkx, 1997). At first glance, andragogy would appear to fit best with individual development goals because of its focus on the individual learner.

Institutional Growth Adult learning is equally powerful in developing better institutions and individuals. For example, HRD embraces organizational performance as one of its core goals (Brethower and Smalley, 1998; Swanson and Arnold, 1997), which andragogy does not explicitly embrace either. From this view of HRD, the ultimate goal of learning activities is to improve the institution sponsoring the learning activity. Thus, control of the goals and purposes is shared between the organization and the individual. The adult learning transaction in an HRD setting still fits nicely within the andragogical framework. However, the different goals require adjustments to be made in how the andragogical assumptions are applied.

Societal Growth Societal goals and purposes associated with the learning experience are illustrated through Paulo Freire’s work (1970). This Brazilian educator sees the goals and objectives of adult education as societal transformation, contending that education is a consciousness-raising process. He says education aims to help participants put knowledge into practice and that the outcome of education is societal transformation. Freire is concerned with creating a better world and the development and liberation of people. As such, the goals and purposes within this learning context are oriented to societal and individual improvement.

Individual and situational differences, the middle ring of the andragogy in practice model, are portrayed as variables. We continue to learn more about the differences that impact adult learning and act as filters that shape the practice of andragogy. These variables are grouped into the categories of individual learner differences, subject-matter differences, and situational differences.

Subject-matter differences may require different learning strategies. For example, individuals may be less likely to learn complex technical subject matter in a self-directed manner. Introducing unfamiliar content to a learner will require a different teaching/learning strategy. Simply, not all subject matter can be taught or learned in the same way.

Situational differences capture any unique factors that could arise in a particular learning situation and incorporate several sets of influences. Different local conditions may dictate different teaching/learning strategies. For example, learners in remote locations may be forced to be more self-directed or perhaps less so. At a broader level, this group of factors connects andragogy with the sociocultural influences now accepted as a core part of each learning situation. Jarvis (1987) sees all adult learning as occurring within a social context through life experiences.

Individual differences may be the area where our understanding of adult learning has advanced the most since Knowles first introduced andragogy. Many researchers have expounded on a host of individual differences affecting the learning process (e.g., Dirkx and Prenger, 1997; Kidd, 1978; Merriam and Caffarella, 2006). The increased emphasis on linking adult learning and psychological research is indicative of an increasing focus on how individual differences affect adult learning. From this perspective, there is no reason to expect all adults to behave the same. Instead, our understanding of individual differences should help shape and tailor the andragogical approach to fit the uniqueness of the learners.

The andragogy in practice model is an expanded conceptualization of andragogy. It incorporates domains of factors that influence the application of core andragogical principles.

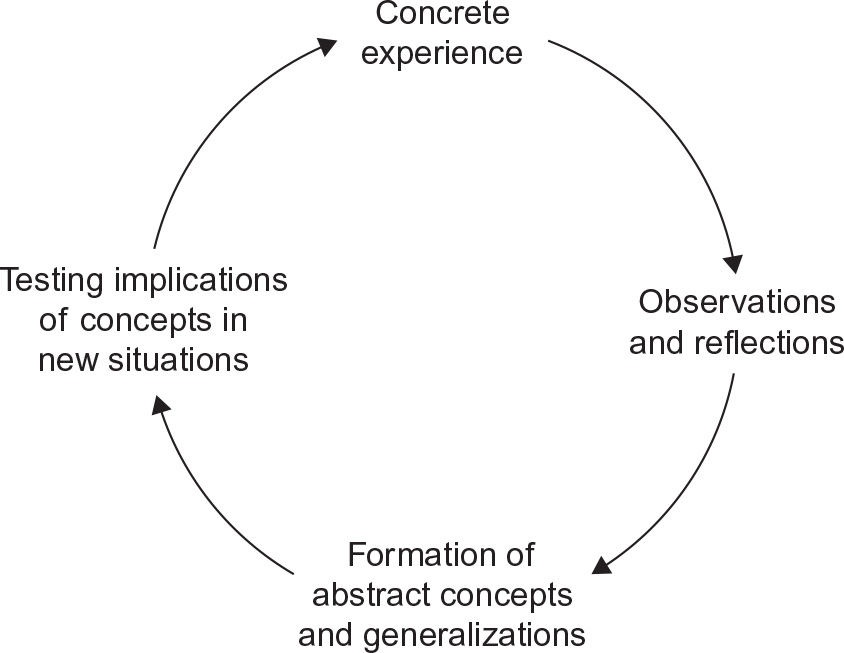

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING MODEL

Kolb (1984) has been a leader in advancing the practice of experiential learning for adults that we most associate with John Dewey (1910; 1938). Kolb defines learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through transformation of experience” (1984, 38). For him, learning is not so much the acquisition or transmission of content as the interaction between content and experience, whereby each transforms the other. The educator’s job, he says, is not only to transmit or implant new ideas but also to modify old ones that may get in the way of new ones.

Kolb bases his model of experiential learning on Lewin’s problem-solving model of action research, which is widely used in organization development (Cummings and Worley, 2001). He argues that it is very similar to Dewey and Piaget’s as well and specifies four steps in the experiential learning cycle (see figure 9.7): (1) concrete experience—being fully involved in here-and-now experiences; (2) observations and reflection—reflecting on and observing their experiences from many perspectives; (3) formation of abstract concepts and generalizations—creating concepts that integrate their observations into logically sound theories; and (4) testing implications of new concepts in new situations—using these theories to make decisions and solve problems.

Figure 9.7: Experiential Learning Model—Kolb

Kolb goes on to suggest that these four modes combine to create four distinct learning styles.

Kolb’s model has contributed to the experiential learning literature by providing (1) a theoretical basis for experiential learning research and (2) a practical model for experiential learning practice. The four steps in his model are an invaluable framework for designing learning experiences for adults. At a macro level, programs and classes can be structured to include all four components, as well as at a micro level, units or lessons. Below are examples of learning strategies that may be useful in each step:

Kolb’s Stage | Example Learning/Teaching Strategy |

Concrete experience | Simulation, case study, field trip, real experience, demonstrations |

Observe and reflect | Discussion, small groups, buzz groups, designated observers |

Abstract conceptualization | Sharing content |

Active experimentation | Laboratory experiences, on-the-job experience, internships, practice sessions |

Research on Kolb’s model has focused chiefly on the learning styles he proposes. Unfortunately, research has done little to validate his theory, due largely to methodological concerns about his instrument (Cornwell and Manfredo, 1994; Freedman and Stumpf, 1980; Kolb, 1981; Stumpf and Freedman, 1981).

While always valuing experience, HRD practitioners are increasingly emphasizing experiential learning as a means to improve performance. Action reflection learning is one technique developed to focus on the learner’s experiences and integrate experiences into the learning process. Transfer of learning researchers are also focusing on experiential learning as a means to enhance transfer of learning into performance (Holton, Bates, Seyler, and Carvalho, 1997; Bates, Holton, and Seyler, 2000) and to increase motivation to learn (Seyler, Holton, and Bates, 1997). Structured on-the-job training (Jacobs, 2003) has emerged as a core method to capitalize more systematically on the value of experiential learning in organizations and as a tool to more effectively develop new employees through the use of experienced coworkers (Holton, 1996c). Experiential learning approaches have the dual benefit of appealing to the adult learner’s experience base and increasing the likelihood of performance change after training.

INFORMAL AND INCIDENTAL WORKPLACE LEARNING

While many people think first of formal training in HRD, much of the learning that occurs in organizations happens outside formal training or learning events. Informal and incidental learning has deep roots in the work of Lindeman (1926) and Dewey’s (1938) notion of learning from experience, although it was Knowles (1950) who introduced the term informal learning.

Watkins, Marsick, and their associates have advanced inquiry on informal and incidental learning (1990, 1992, 1997, 2015). They define the elements in this way:

Formal learning is typically institutionally-sponsored, classroom-based, and highly structured. Informal learning, a category which includes incidental learning, may occur in institutions, but is not typically classroom-based or highly structured, and control of learning rests primarily in the hands of the learner. Incidental learning is defined as a byproduct of some other activity, such as task accomplishment, interpersonal interaction, sensing the organizational culture, trial-and-error experimentation, or even formal learning. Informal learning can be deliberately encouraged by an organization or it can take place despite an environment not highly conducive to learning. Incidental learning, on the other hand, almost always takes place although people are not always conscious of it. (Marsick and Watkins, 1990, 12, emphasis added)

Thus, informal learning can be either intentional or incidental. Examples of informal learning include self-directed learning, mentoring, coaching, networking, learning from mistakes, trial and error, and so on. Incidental learning can also lead to embedded assumptions, beliefs, and attributions that can later become barriers to other learning. Argyris (1982) and Schon (1987) refer to double loop learning (or reflection in action) as the learning process required to challenge the implicit or tacit knowledge that arises from incidental learning. Tacit knowledge is increasingly recognized as an important source of knowledge for experts and innovation (Glynn, 1996).

Marsick and Watkins (1990, 1997) and Cseh, Watkins, and Marsick (1999) have developed a model of informal and incidental learning where learning is embedded within the individual’s daily work and is highly contextual. Furthermore, they contend that learning occurs due to some trigger (internal or external) and an experience. This is in sharp contrast to the planned learning approach of formal learning events.

The question of whether informal or incidental learning can and should be facilitated is unsettled. On the one hand, it seems that there are efforts HRD organizations should use to facilitate the process. For example, Raelin (2000) suggests using action learning, communities of practice, action science, and learning teams in management development to encourage informal work-based learning. Piskurich (1993) takes a similar approach to self-directed learning, while Jacobs (2003) and Rothwell and Kasanas (1994) advocate a structured approach to on-the-job training. Realistically, attempting to overfacilitate informal and incidental learning gets to the point that they become formal learning.

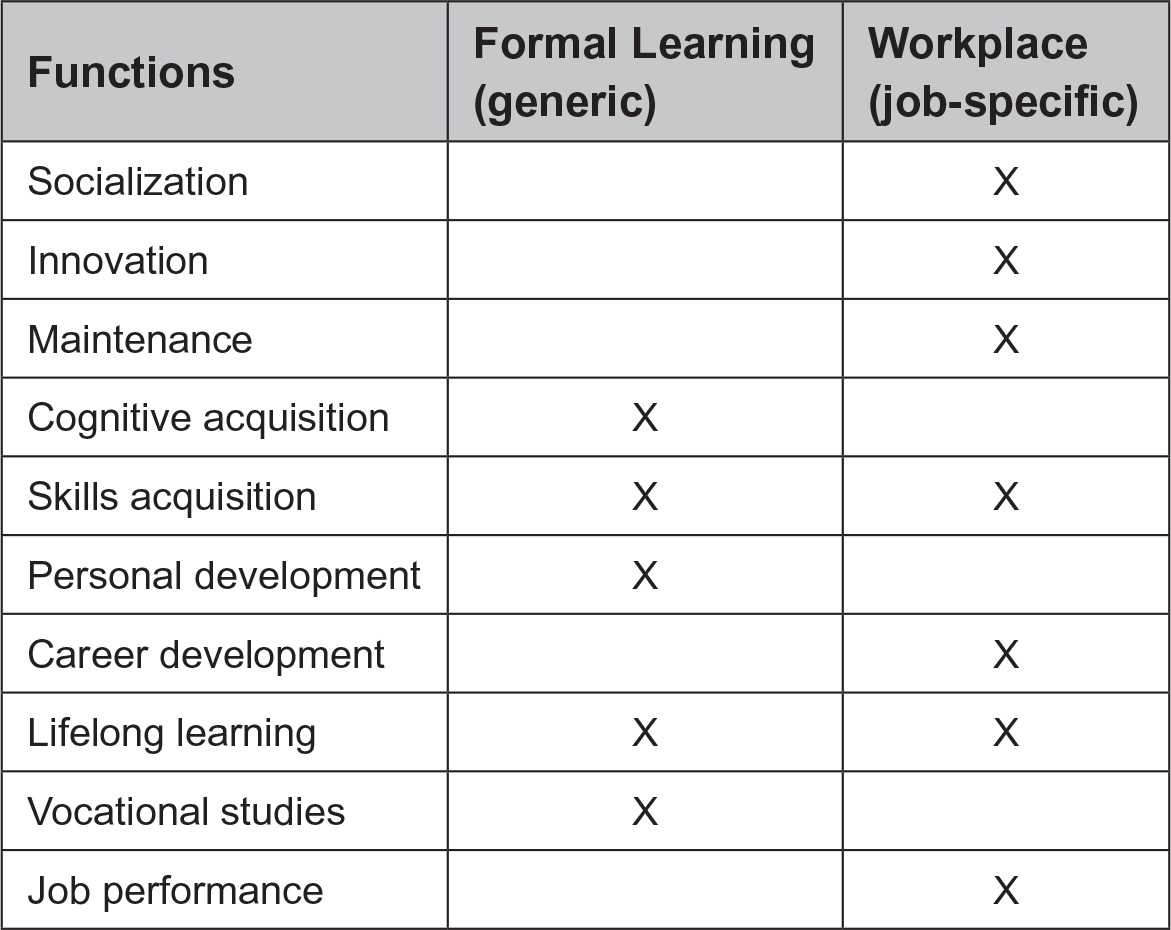

Nijhof and Nieuwenhuis (2008) published an up-to-date analysis of work-place learning related to HRD in their book titled The Learning Potential of the Workplace. They note, “Learning is becoming a constituent part of work. Anthropologists would smile, because it is their main belief that lifelong learning in context is the essence of mankind, and therefore an integral part of what people do, including work” (4). Yet, one conclusion is that there are misconceptions about learning in the workplace and that the workplace is not always an effective learning environment (Nijhof, 2006). Figure 9.8 profiles learning functions as being most appropriate in a classroom or workplace setting.

Figure 9.8: Functions of Schooling and Learning Settings

Source: Nijhof and Nieuwenhuis, 2008, 5. Used with permission.

Throughout this discussion of informal workplace learning, it is critical to highlight unstructured and structured on-the-job learning ideas. Unstructured is equivalent to informal workplace learning, and structured on-the-job training uses the actual workplace as a learning setting.

“The learning potential of the workplace should be proved by evidence that students and employees learn something that changes their behavior with durable results—cognitive, affective, technical, and social. While the workplace is a place to work and perform, learning is an intermediate condition, and the learning potential of the workplace therefore lies in its condition to support or stimulate learning” (Nijhof and Nieuwenhuis, 2008, 5).

TRANSFORMATIONAL LEARNING

Transformational learning has gained increasing attention in HRD. The fundamental premise is that people, just like organizations, may engage in incremental learning or deeper learning that requires them to challenge fundamental assumptions and meaning schema they have about the world. This concept has appeared in a variety of forms in the literature.

Argyris (1982) labels learning as either single-or double-loop learning. Single-loop learning is learning that fits prior experiences and existing values, enabling the learner to respond automatically. Double-loop learning does not fit the learner’s prior experiences or schema and generally requires learners to fundamentally change their mental schema. Similarly, Schon (1987) discusses “knowing in action” and “reflection in action.” Knowing in action refers to the somewhat automatic responses based on our existing mental schema that enable us to perform efficiently in daily actions. Reflection in action is reflecting while performing to discover when existing schema are no longer appropriate and changing those schemas when appropriate.

Mezirow (1991) and Brookfield (1986, 1987) have been leading advocates for transformational learning in the adult learning literature. Mezirow (1991) calls this perspective transformation, which he defines as “the process of becoming critically aware of how and why our assumptions have come to constrain the way we perceive, understand, and feel about our world; changing these structures of habitual expectation to make possible a more inclusive, discriminating, and integrative perspective; and finally, making choices or otherwise acting upon these new understandings” (167).

The concept of deep transformational change is found throughout the HRD literature. Many believe that transformational change at the organizational level is not likely to happen unless transformational change occurs at the individual level through some process of critically challenging and changing internal cognitive structures. Furthermore, without engaging in deep learning through a double-loop or perspective transformation process, individuals will remain trapped in their existing mental models or schemata. It is only through critical reflection that emancipatory learning occurs and enables people to change their lives at a deep level.

Learning Models at the Organizational Level

While individual learning has long dominated HRD practice, in the 1980s and particularly the 1990s, increased attention turned to learning at the organizational level. The literature refers to two related but different concepts: organizational learning and learning organizations. A learning organization is a prescribed set of strategies that can be enacted to enable organizational learning. It is important to recognize that organizational learning is different and that the terms are not interchangeable.

Organizational learning occurs at the system level rather than at the individual level (Dixon, 1992). It does not exclude the learning that occurs at the individual level. But, it is greater than the sum of the learning at the individual level (Fiol and Lyles, 1985; Kim, 1993; Lundberg, 1989). Organizational learning is more specifically defined as “the intentional use of learning processes at the individual, group and system level to continuously transform the organization in a direction that is increasingly satisfying to its stakeholders” (Dixon, 1994, 42). It is learning keenly perceived at the system level, and it arises from processes surrounding the sharing of insights, knowledge, and mental models (Strata, 1989).

A key element differentiating individual and organizational learning revolves around mental models (Kim, 1993). When individuals make their mental models explicit and organizational members develop and take on shared mental models, organizational learning is enabled. Learning becomes organizational learning when these cognitive outcomes, the new and shared mental models, are embedded in members’ minds, and in . . . artifacts . . . in the organizational environment (Argyris and Schon, 1996). Organizational learning is embedded in the culture, organizational systems, work procedures, and processes.

LEARNING ORGANIZATION STRATEGY

The learning organization became a focus of attention in the organizational literature in the 1990s and has continued. Interest in this organization development (OD) intervention has been spurred by the constantly changing work and business environments, prompted by technological advances, increased levels of competition, and the globalization of industries. Senge and other researchers have described the characteristics of the learning organization and made suggestions for organizational implementation (Kline and Saunders, 1993; Marquardt, 2002; Pedler, Bourgoyne, and Boydell, 1991; Senge, 1990; Watkins and Marsick, 1993).

The dimensions commonly described in the literature as associated with a learning organization are not new concepts, but their coordination into a system focused on organizational learning is. Senge (1990, 13) defines a learning organization as “a place where people are continually discovering how they create their reality.” Watkins and Marsick (1993, 8) define it as “one that learns continuously and transforms itself.” A comprehensive definition of a learning organization is offered by Marquardt (1996, 19): “an organization which learns powerfully and collectively and is continually transforming itself to better collect, manage, and use knowledge for corporate success. It empowers people within and outside the company to learn as they work. Technology is utilized to optimize both learning and productivity.”

There appears to be some common recognition and agreement about the core characteristics of a learning organization. Researchers suggest that individuals and teams work toward the attainment of linked and shared goals, communication is open, information is available and shared, systems thinking is the norm, leaders are champions of learning, management practices support learning, learning is encouraged and rewarded, and new ideas are welcome (Marquardt, 2002; Senge, 1990; Watkins and Marsick, 1993). The learning outcomes found in a learning organization are expected to include experiential learning, team learning, second-loop learning, and shared meaning (Argyris, 1977; Argyris and Schon, 1978; Dodgson, 1993; Senge, 1990). As a result of this learning, organizations are believed to be capable of new ways of thinking.

Learning Organization Model Peter Senge (1990) is credited with popularizing the learning organization. In laying out the foundation for his model of the learning organization, Senge (1992, 1993) speaks about the three levels of work required of organizations. The first level focused on the development, production, and marketing of products and services. This organizational task is dependent on the second level of work: the designing and development of the systems and processes for production. The third task undertaken by organizations centers around thinking and interacting. The first two levels of organizational work are affected by the quality of this third level (Senge, 1993). The quality of the organizational thinking and interacting affects the organizational systems and processes and the production and delivery of products and services. This belief places organizational thinking in a pivotal position affecting the ability of an organization to accomplish goals and perform effectively.

It is the third level of organizational work that Senge addresses with his concept of learning organizations. In defining a learning organization, he notes, “We can build learning organizations, where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together” (1990, 3).

Senge (1990) states that organizations need to develop five core disciplines or capabilities to accomplish the following defined goals of a learning organization:

• Personal mastery

• Mental models

• Shared vision

• Team learning

• Systems thinking

Systems thinking, the fifth discipline, acts to integrate the other four disciplines. It is described as the ability to take a systems perspective of organizational reality. Senge (1990) discusses strategies that organizations can implement. The recommended methods involve the following organizational variables: climate, leadership, management, human resource practices, organization mission, job attitudes, organizational culture, and organizational structure.

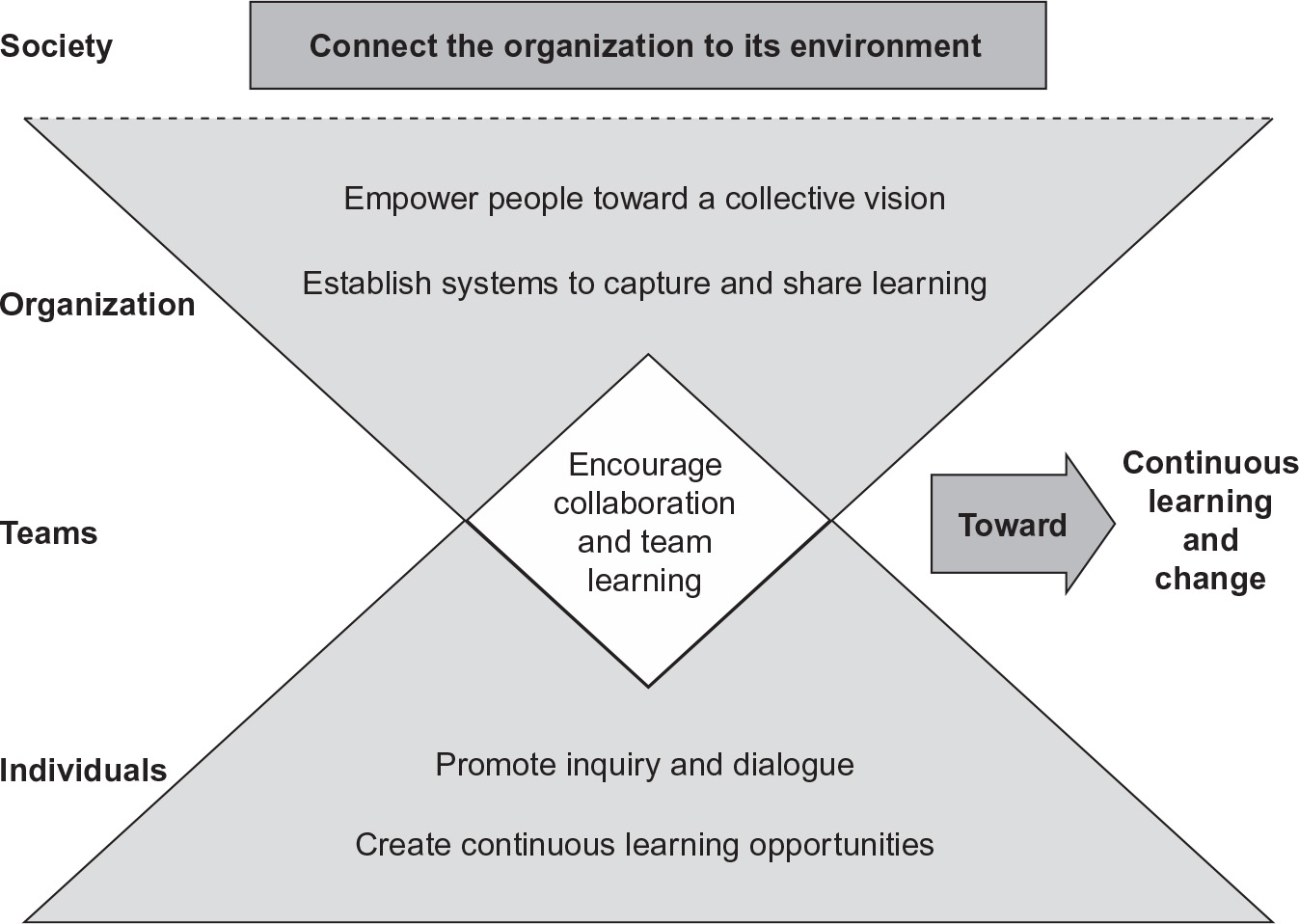

Watkins and Marsick (1993) posit that learning is a constant process and results in changes in knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors. They also note that, in a learning organization, the learning process is a social one and takes place at the individual, group, and organizational levels. They propose six imperatives that form the basis for the organizational strategies recommended to promote learning:

1. Create continuous learning opportunities.

2. Promote inquiry and dialogue.

3. Encourage collaboration and team learning.

4. Establish systems to capture and share learning.

5. Empower people toward a collective vision.

6. Connect the organization to its environment.

Figure 9.9 illustrates the interrelationship of these six imperatives across the individual, team, and organizational levels.

These six imperatives are similar to the disciplines suggested by Senge (1990, 1994). Marquardt (1996) similarly focuses on a learning system composed of five linked and interrelated subsystems related to learning: the organization, people, knowledge, technology, and learning. Most learning organization models appear to focus on the values of continuous learning, knowledge creation and sharing, systemic thinking, a culture of learning, flexibility, experimentation, and finally, a people-centered view (Gephart et al., 1996).

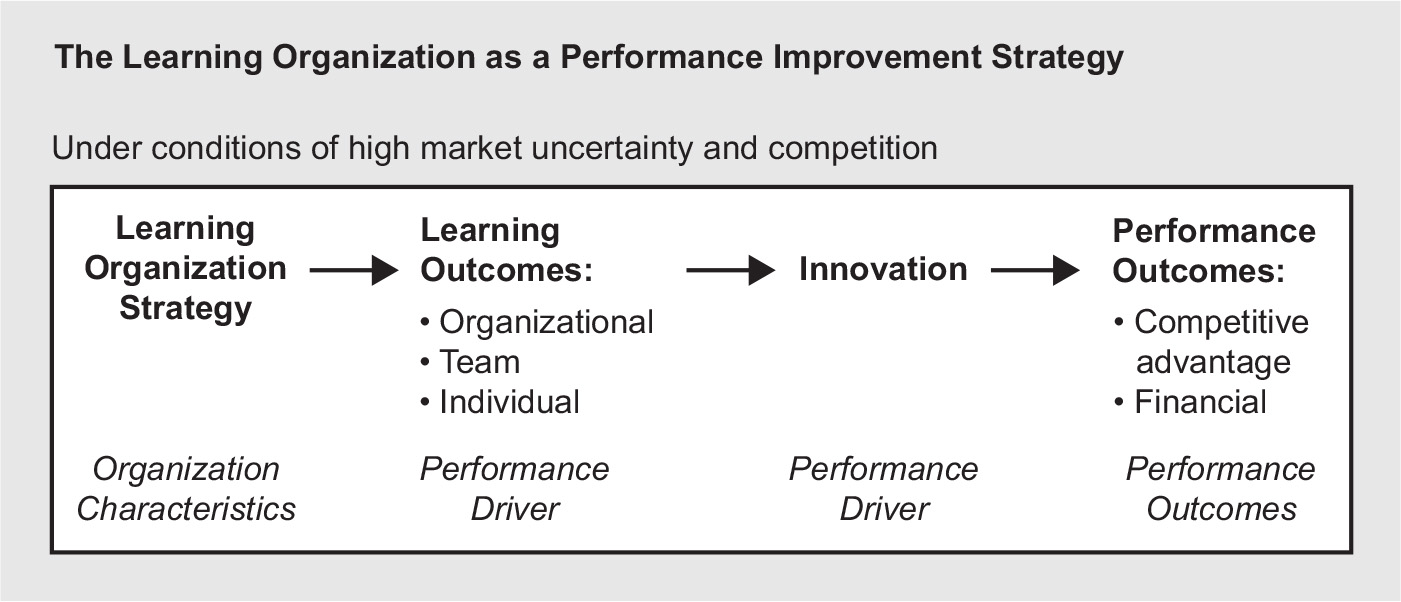

LEARNING ORGANIZATION AND PERFORMANCE OUTCOMES

Much of the learning organization literature is conceptual and descriptive. While there are numerous descriptive accounts and suggestions about why the process works, there are limited concrete descriptions about how it works to improve performance. Learning organizations perceive learning as the means to long-term performance improvement (Guns, 1996). However, there is little empirical data supporting the claim that performance improvement is directly related to the adoption of the learning organization’s strategies. Exceptions include a study showing improved firm performance associated with learning organization strategies (Ellinger et al., 2000) and another showing that learning organization strategies are related to perceived innovation (Holton and Kaiser, 2000).

Figure 9.9: Learning Organization Action Imperatives—Watkins and Marsick

Source: Watkins and Marsick, 1993, 10. Used with permission.

Innovation is perceived to be the critical link between learning organization strategies and performance (Kaiser and Holton, 1998). The learning organization and the innovating organization are both dependent on the acquisition of information, interpretation of information, creation of meaning, and creation of organizational knowledge. The stated end goal of both the learning system and the innovating system is improved organizational performance. The similarities between the two literatures are striking: the linking pin for both is knowledge; the goal in both is performance improvement.

A comparison of both literatures concludes that the organizational strategies engaged to support the learning and innovating endeavors are similar and suggest parallel strategies (Kaiser and Holton, 1998). Innovation appears to be affected by culture, climate, leadership, management practices, dynamics of information processing, organizational structure, organizational systems, and the environment.

Figure 9.10: Learning Organization performance Model

Source: Kaiser and Holton, 1998.

The conceptual model in figure 9.10 is based on the review of the learning organization and innovation literatures and the parallel sets of variables and theorized relationships to performance improvement (Kaiser and Holton, 1998). This model hypothesizes that learning organization strategies increase learning and innovation (performance drivers), improving performance outcomes. This hypothesized model of the learning organization as a performance improvement strategy supports the following conclusions:

• Learning—particularly improved learning at the team and organizational levels—leads to increased organization innovation.

• Adopting learning organization strategies is appropriate for organizations in markets where innovation is a key performance driver.

• Innovation is expected to result in improved performance outcomes, leading to a competitive advantage for the organization.

Conclusion

The good news for HRD is that learning has never been as highly regarded in organizations as it is today. HRD is called upon for developing knowledge and expertise in organizations that enable them to be competitive in a challenging global economy. HRD must continue to research and define effective learning processes. While much is known about learning, much remains to be discovered about learning in the workplace.

Reflection Questions

1. Think about the five learning theories discussed in this chapter. Which is most attractive to you, and why?

2. Think about the four learning models at the individual level presented in this chapter. Which is most attractive to you, and why?

3. How can the andragogy in practice model be applied to enhance the learning that takes place through HRD?

4. Do you believe that organizations can learn? Or, are organizations merely the sum of individual learning? Take a position and explain.

5. If learning is a defining construct for the HRD, how can learning be made more powerful in organizations?

Internet Resources. Instructional support materials for this chapter can be found on this website: www.texbookresources.net