19

Policy and Planning for Human Resource Development

CHAPTER OUTLINE

• The Work of HRD and Its Host Organization

• Fostering Alignment and Tension

Human Resource Development Policy and Planning

Contributed by Toby M. Egan, University of Maryland

• Human Resource Development Value Chain

• Human Resource Development Policy

• Levels of Human Resource Development Policy and Planning

• Human Resource Development Planning

Introduction

Human resource development (HRD) policy and planning is an important realm of professional activity that is generally in the hands of the top HRD leaders in an organization or system. This planning work can be thought of as a component of, or aligned with, organizational strategy.

THE WORK OF HRD AND ITS HOST ORGANIZATION

Most discussions related to HRD policy and planning are connected to program management. As an extension of HRD management, the case is regularly made for leadership skills related to project management, including a strong case for planning skills and the ability to promote collaboration (Gilley, Eggland, and Gilley, 2002).

Given organizational demands for effectiveness and efficiency, HRD upper-level managers and administrators should ensure that they and their project managers have adequate planning, controlling, and communication expertise (Fabac, 2006). Additionally, having a clear HRD mission, policies, and defined processes promotes clear expectations and is fundamental to consistent organizational success.

HRD adds value in helping its host organization through development efforts. HRD is not a desk-bound profession. HRD professionals are students of their organizations, getting directly involved in the work and with the people doing it. In helping to advance the performance of their organizations, HRD gets involved in maintaining the systems and in changing the systems. From an HRD operations point of view, it is recommended that development efforts from these two perspectives be kept discrete to avoid confusion and conflict.

FOSTERING ALIGNMENT AND TENSION

Almost all organizations are concerned about efficiency and effectiveness. Efficiency is generally the easiest target to see. Things like cutting costs, going faster, and doing more with less are by themselves not worthy if the goods and services being produced lose their quality. There is a healthy tension between the pursuit of effectiveness and efficiency. HRD professionals require an understanding and appreciation of this dynamic.

There is another level of tension where HRD professionals are less likely to involve themselves. The natural partnership between HRD and the quality movement is fed by the notion of alignment (Semler, 1997), or getting people and processes all on the same page—agreeing and harmonizing. Carried to an extreme, the reengineering movement (Hammer and Champy, 1994) forwarded the mantra of “carry the wounded and shoot the stragglers.” Those that resisted alignment were ousted. The human dimension and openness to critique were lost in reengineering, and the movement faltered (Davenport, Prusek, and Wilson, 2003; Swanson, 1993).

The paradox for HRD is to deal with the need for harmony and dissent—enough harmony for the short term and enough dissent for needed renewal. There is clear evidence that both creativity and innovation in organizations comes from individuals working outside the regimen of the organizational systems (Kelly, 2001).

To foster corporate creativity and innovation, there is a call for HRD professionals and their host organizations to establish understandings and policies that address alignment, self-initiated activity, unofficial activity, serendipity, diverse stimuli, and intracompany communication (Robinson and Stern, 1997).

Human Resource Development Policy and Planning

Contributed by Toby M. Egan, University of Maryland

The resource-based view of organizations (Wernerfelt, 1984) postulates that employee knowledge and skill are important sources of competitive advantage (Garavan, 2007) and add value to the well-being and capacity of broader society (Woodall, 2001). From a human capital theory perspective, the capacity of any organization or system is rooted in individual expertise and collective core competencies. Organizations protect their core capabilities and capacity by utilizing HRD—and its aims toward learning and performance—to advance their mission and goals and to react to the changing environment (Becker, 1993). HRD research has effectively demonstrated connections between HRD practices, learning, and organization performance (Akdere and Egan, 2020; Egan, Yang, and Bartlett, 2004). As organizational and large system goals expand and become more complex, the need is for policy and planning to be more rigorously pursued.

What is policy and planning? How do they relate to HRD? As an organized, systematic process and function, HRD is deployed at individual, group, organization, regional, state/provincial, national, and even international levels (Garavan, McGuire, and O’Donnell, 2004). In order to deploy HRD within any organization or system, policy and planning is involved. Policy provides an intentional system of principles for action based on strategic priorities that specify the course and timeline for related planning. HRD policy and planning is a critical catalyst within and between the aforementioned levels. It is necessary to guide and coordinate HRD related processes toward common goals. HRD planning is a continuous system-focused process aimed toward maximization of employee outcomes aligned with mission, vision, learning, and performance goals that are guided by policy. HRD planning is used to create the best likelihood that the current workforce is aligned to serve customers, stakeholders, and the impact the organization was designed to achieve.

HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT VALUE CHAIN

The concept of organizational value chain (Porter, 1985) emphasizes using organizational systems to transform inputs into outputs. Beneath the creation and sustainability of superior performance is policy and planning. The value chain concept refocuses thinking about organizational productivity by framing organizations and their processes as key to meeting expectations for customers and stakeholders. HRD practice should support the organizational value chain not only as a matter of alignment with organizational strategy, structure, and goals, but also as a logical connection to systems theory regardless of sector—for-profit, nonprofit, or governmental (Jacobs, 1989). The HRD value chain should be designed to directly support primary organizational activities—inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service (Porter, 1985). Although the terminology used may be different in nonprofit or governmental settings, the core notion of the HRD value chain contributes to the key strategic focus of organizations by contributing to the primary activities of an organization or large system.

The HRD value chain brings (1) focus and supports, (2) learning, and (3) performance resulting in (4) proven customer outcomes that are a key indicator of sustained organizational performance (Leimbach and Baldwin, 1997). According to AIHR Analytics (2020), such a people development–oriented value chain contributes to organizational performance results and centers HRD-related practices as a critical contributors to long-term success. Only recently have substantial empirical studies that include customer and stakeholder outcome data begun to verify previously anecdotal evidence supporting the HRD value chain—connecting HRD practices to organizational performance outcomes (e.g., customer satisfaction; Akdere and Egan, 2020). These positive findings support the importance of the underlying mechanisms that bolster the HRD value chain and performance outcomes—HRD policy and planning.

HRD policy and planning is fundamentally about achieving sustained performance and accountability through actively crafting a talented workforce. Such policy and planning is most often shaped and guided by HRD leaders in collaboration with governance and management teams. When well-formulated, HRD policy becomes a necessary tool in executing core strategies, innovation, performance, learning and development, and desired outcomes.

HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT POLICY

Policy is defined as a deliberate, broad-based, high-level plan framing and embracing general goals and aligned procedures (Wognum, 2001). It is established through laws, regulations, procedures, administrative actions, incentives, or the voluntary practice of organizations, institutions, and governments. Policy decisions are frequently reflected in resource allocations. The largest scope of policy is international and national policy, with the smallest being organizational and departmental policy. Although policy in organizational human resources contexts has been used to differentiate HRD from human resource management (HRM), HRD is frequently tied to policies that set expectations for how it is deployed, utilized, resourced, and evaluated (McLagan, 1989a). Policies are important tools to create the greatest impact on learning and performance. In several sections of this chapter, training will be used as an example of HRD policy and planning. Examples of training-related HRD policy and planning may include mandatory training and certification; utilization of evidence-based training research and results; and establishing processes for training design, development, implementation, and evaluation. In addition to organization-level considerations, HRD policy is found at international, national, state/provincial, municipal and community levels.

LEVELS OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT POLICY AND PLANNING

In today’s knowledge and service economies, a skilled and productive workforce is central for success and the agility required to adjust to ongoing changes. National and organizational success is interdependent, as both broad workforce development and organization-specific training contribute to growth and, ultimately, global capacity building (Rothwell, Gerity, and Gaertner, 2004). Human capital developed through effective HRD practices is central to economic growth. It is also dependent on a comprehensive strategy aligning learning, development, and training with governmental labor market policies. Whether at a large systems level or a part of a single organization’s leadership team, HRD professionals skilled in policy and planning enable purposeful operational alignment (Wognam, 2001). Ideally, governments develop comprehensive and coherent HRD policy frameworks reflecting a broader strategy. Policy and planning relate to the implementation capacity to deploy HRD-related solutions toward defined aims.

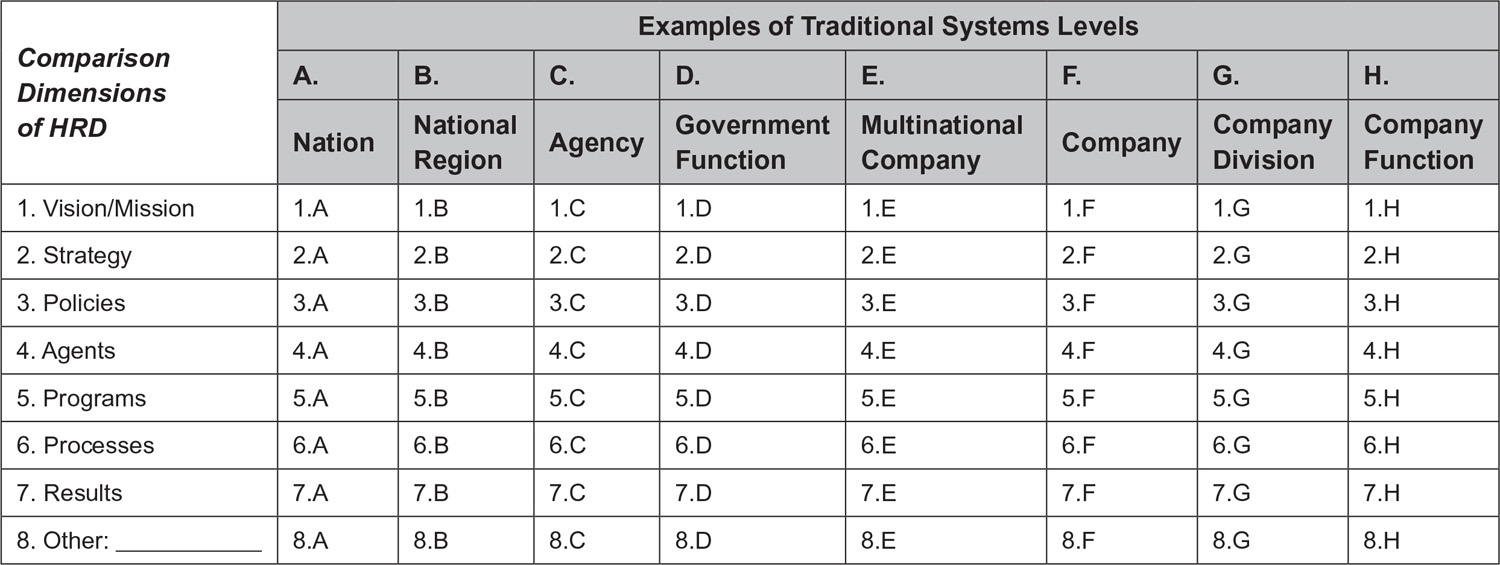

To support HRD professionals in framing and analyzing economic entities from a comparative perspective, Wang and Swanson (2008) developed a Comparative Study Framework for Human Resource Development (figure 19.1). This generalizable approach examines a specific organizational entity from vision/mission to specific results not dependent on a particular type of operation or industry, size, location, culture, or history. As represented in the left vertical column in figure 19.1, such entities can range from a small family business to an entire country.

On the horizontal axis, the system level of an entity is selected (1.A–1.H). The entity can be a single function within an organization, community, or nation. In order to be able to set the direction for HRD activities, HRD professionals determine established vision/mission for the entity being assessed. Once the direction of the host organization is determined, the HRD function can be effectively aligned, therefore ensuring value-added HRD to the entire organization. At the following level, corresponding HRD strategy and related policies are formed in alignment with the focal entity. Subsequently, HRD implementation of programs and processes fits well within subsequent goals and objectives. Throughout HRD deployment, HRD professionals engage in ongoing assessment processes and improvement efforts aimed at effective and efficient learning and performance. Related results can be compared against all levels, including high-level vision/mission, strategy, and policy to determine current alignment and potential for adjustments based on constructive feedback and data analysis. This systems-level approach to calibrating and establishing HRD alignment extends well beyond episodic evaluation toward comprehensive discovery.

Figure 19.1: Comparative Study Framework for Human Resource Development*

* Using all or selected Comparison Dimensions of HRD (1–8), comparisons are typically between selected, rival, or parallel systems (A–H). For example, one corporation compared to another corporation, or one country compared to another.

Source: Wang and Swanson, 2008.

Within figure 19.1, the term other can be utilized and defined broadly to national contexts, industries, markets, the stakeholder environment, or other elements of internal and external dimensions of a focal entity. Along with setting HRD direction from this framework, it can also support the establishment of benchmarking, best practices, and comparative research, including HRD policy analysis. This type of research can be conducted across (A–H) industries, in comparing crossnational (e.g., regional differences within the same financial services firm) or international organizations with parallel missions and operations (e.g., Amazon versus Alibaba), within or even between sectors (e.g., for-profit versus nonprofit versus government healthcare organizations). By conducting such comparisons, HRD professionals can establish best practices, determine relative competitiveness, and set aspirational outcomes. Aspirational outcomes are aligned with policy and planning goals, the scope of which depends on the vantage point of the stakeholders and the HRD professional.

Large System Human Resource Development Policy The broadest framing of HRD policy was first described by Harbison and Myers (1964) who framed HRD strategy in relation to education, human capital, and economic growth in approximately 90 percent of the world population. These economists established the centrality of HRD for national success and the value chain of economic planning toward expanded human capital and, ultimately, improved economic growth. The capacity and adaptability of the labor force is a critical driver in forming foreign and domestic enterprises regardless of industry or sector—for-profit, nonprofit, or governmental (OECD, 2014). The United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals reflect the framing of HRD brought forth by Harbison and Myers by broadly defining HRD and recommending necessary steps for advancement across the globe. “Current patterns of growth have reaffirmed the centrality of human resource development both as a goal in itself and as a means to achieve equitable, inclusive and sustainable growth and development” (United Nations, 2013). With the broadest framing of HRD came a set of eight strategic goals reflecting the needs of the global populace—(1) eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; (2) achieve universal primary education; (3) promote gender equality and empower women; (4) reduce child mortality; (5) improve maternal health; (6) combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; (7) ensure environmental sustainability; and (8) maintain global partnership for development (United Nations, 2013). As might be expected, these goals address collective critical needs across humanity. Importantly, the UN views HRD policy and planning to be a central mechanism for accomplishing sustainable global social, environmental, and economic growth.

To accomplish these global goals, UN leadership (United Nations, 2013) recommended that (1) science, technology, and innovation (STI) and HRD systems should be well integrated into all national development strategies; (2) strategies should be accompanied by HRD policies attuned to future labor market needs across all sectors; (3) increasing science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education and employment opportunities, particularly for women, youth, and other disadvantaged groups is critical; (4) STI participation should involve policies and investment that support the innovation chain of government, universities, research institutions, and businesses; (5) government plays a key role in setting in place adequate infrastructure, institutions, policies, and incentives for all relevant contributors to promote STI for society as a whole; (6) the private sector plays a key critical role in transforming the outcomes of scientific research, new technologies, and ideas into new commercial products and services and supporting a culture of innovation and learning; and (7) the international community has an obligation to diffuse innovation in a manner that creates new internationalized, collaborative, and open innovation models that make STI innovations accessible across the globe (United Nations, 2013). The Millennium Development Goals depend on HRD strategies, policies, and planning that are crucial to establishing sustainable social progress, environmental sustainability, and long-term economic growth.

Implicit in the UN’s framing of HRD, governmental systems commonly engage in policy formation aimed at developing citizens’ capacities for work. Increasingly, HRD policymakers are exploring creative ways to preserve labor market dynamism while providing employees adequate security (OECD, 2019a). Four key areas of emphasis at the governmental level include (1) facilitation of labor force talent and competency development, (2) addressing product and labor market impediments to labor demand, (3) removing obstacles to labor workforce development, and (4) sustaining microeconomic fundamentals. As reflected in the formation of aspirational international policy, the UN included health and well-being as integral to HRD at the local and organizational levels.

HRD is planned across the human lifespan (Jung and Takeuchi, 2018). This includes government policies that provide for workforce training and retraining across the span of options—from academic degrees and certificates to on-the-job training and apprenticeships. Such governmental policies impact organizational decision making through business strategies, external and internal labor market needs, development capacity, and external support for training (McLean, 2006). Considering HRD at the global level can seem overwhelming, but this perspective provides crucial insights into the notion that there are common principles for HRD policy and planning regardless of the scope. From the UN’s 195-country perspective to a single nation, state/province, multinational organization, or even small business or nonprofit, HRD policy is designed to elaborate upon a learning and development course of action aimed toward achieving desired performance outcomes. In the midst of the large system policy environment, organizations need to be responsive to increasingly evolving and complex environments. Therefore, it is more important than ever before to implement HRD policies and planning that advance organizational performance.

Human Resource Development Policy at the Organization Level It is critical that HRD policy reflect the strategic interests of organizations. The HRD policymaking process should be based on a systems-level analysis of organizational mission, strategy, goals, processes, and feedback systems. A key focus should be alignment of learning and development with key performance indicators (Alagaraja and Shuck, 2017; Semler, 1997). Ideally, policy formation will be evidence-based—both broadly from HRD research and based on internal systems, processes, and outcomes. HRD policymaking is a multilevel, interactive process whereby HRD policy leads to the formation of HRD goals/objectives. These goals/objectives both support existing aligned HRD programs and lead to the formation of additional activities aimed at employee competency acquisition that addresses needed performance improvement for greater organizational efficiency and effectiveness. Such policies can span from requiring licenses and certifications and mandatory training to internal online learning libraries and funding for external learning programs (even college tuition reimbursement).

An area of HRD policy most common to organizations is related to training. For the organizational leaders and HRD practitioners with scholarly-practitioner orientations, training provides an opportunity to align both research-based and situational evidence in forming HRD policy. By reviewing available research organizations, one will find a mounting evidence base to guide HRD policy related to training that has grown substantially over the past thirty years (Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger, and Smith-Jentsch, 2012). Training research is grounded in the science of learning, theoretically based, empirical in nature, and specifically applicable to organizational contexts.

Overall, research on HRD supports the efficacy of organizational training and managerial and leadership training, team training, and behavior modeling. Research also supports a systems approach to training and development, including conducting needs analysis, job-task analysis, organizational analysis, and individual-level competency analysis. Learning climate, the use of instructional principles, technology utilization, training evaluation, and support from supervisors and leaders have all been key contributors to training effectiveness (Salas et al., 2012). A learning transfer systems approach supported by research evidence (Holton and Baldwin, 2003) has practical implications that can be applied in any firm toward improved training results and the ultimate goal of individual and organizational impact. Therefore, organizations serious about HRD develop training policies that reflect these evidence-based practices. In addition to research-based policymaking, policies that support customized interventions aligning with industry standards, firm-specific knowledge, customer-and stakeholder-related data, and other key performance metrics will advance organizational impact. Such policies set expectations for the learning environment, the process for producing training, pre-/post-training practices, and data use for both the formation and evaluation of training transfer and related outcomes. Ultimately, organizations should be able to point to the ways that performance management systems are tied to training and support feedback loops that allow for better understanding of multilevel competency development and organizational performance.

HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT PLANNING

Once overlooked as an important element of economic and organizational wellbeing, human capital and HRD planning are considered key elements for survival and success. This has become especially true in service delivery economies where the effects of human capital in relation to investment and return on investments (Becker, 1993) and related planning processes where HRD is a central consideration (Zula and Chermack, 2007). From the perspective of renowned economists like Gary Becker (1993), human capital analysis and planning is dependent on HRD, learning, and development.

HRD planning is essential to effectiveness at all aforementioned levels because of the importance of human capital alignment. Ideally, the best HRD planning efforts lead to well-prepared personnel in well-defined roles and possessing requisite competencies to perform efficiently and effectively. Ideally, HRD planning serves system-wide organizational development goals through integration of strategic priorities with environmental demands. In general, planning involves setting and/or support of goals, policies, and procedures within an organization or system (Wang and Swanson, 2008). Within organization contexts, HRD planning is most commonly tied to program planning and project management. The most traditional example of HRD planning involves the thoughtful alignment of learning and development activities with organizational goals. HRD-sponsored efforts could be planned to align with compliance policies (e.g. safety procedures, soft skills, customer service), required certifications (e.g., Lean Six Sigma, skilled trade licensure, professional software certificates), or policies regarding expectations for promotion. Such examples are often tied to larger organizational strategy. However, HRD can also be framed from a multilevel perspective—by individual, group, organizational, industry, country, or even among international trading partners.

Those engaged in HRD planning seek to ensure that present and future needs are addressed, with an eye to the future including (a) the right number of employees (b) assigned to meet established organizational needs (c) who have needed talents, skills, and knowledge (d) aligned, proactive attitudes toward work with a (e) capacity to work effectively with stakeholders and who (f) are cost effective in supporting organizational goals and objectives (Farndale, Pai, Sparrow, and Scullion, 2014).

Sound HRD planning involves (a) effective task analysis at the organizational and unit levels, (b) establishment of comprehensive organizational HRD needs, (c) gap analysis between needs and current state HRD capacity, (d) resource allocation, and (e) establishment of short- and long-term HRD needs across the organization. Many practitioners and scholars view HRD-related planning to be focused on broad strategic plans through the alignment of organization development, training, and individual development. Deployment of learning organization–oriented approaches involve analysis of learning and development efforts and anticipated needs for organization-wide HRD efforts across the socio-technical span, unit-specific planning and action, individually focused knowledge and skill development. Such strategies should not only focus on HRD-related activity development but should also clearly connect to key performance outcomes that extend to organizational competitive advantages and anticipated future HRD-related demands (Jang and Ardichvilli, 2020). It is critical that such alignment requires organization development (OD) integration with HRD practice and that the focus is on measurable achievements (Rao and Rothwell, 2000).

Related resources are a key element of HRD planning that involve the procurement and/or development of a workforce well aligned with identified needs. The desired resourcing outcome is managers and employees with the needed talents, abilities, skills, and knowledge along with motivation to learn and a willingness to transfer new learning. Related resourcing plans clarify internal talent and assets and the extent to which they align with key strategic aims. The ultimate aim of HRD resource planning is to maximize the capacity of a system or organization through the formation of a workforce endowed with the capacity, knowledge, and skills; the capacity for ongoing learning; and the ability to successfully transfer new learning to workplace applications (Keep, 1989). A crucial element in HRD policy and planning is the identification and elaboration of ongoing learning and performance standards with an eye on responding to anticipated needs and to the changing environment while also expanding capabilities for innovation.

According to Armstrong (2000) two elements associated with such planning are (1) resourcing plans and (2) flexibility plans. A final element is systemwide learning transfer plans that support the application of resources across the organization (Holton and Baldwin, 2003). Resourcing plans involve identifying people from within the organization to support in learning new skills and, when needed, searching outside of the organization for more skilled candidates. Flexibility plans maximize the adaptability in using HRD to enable the best utilization of people and respond rapidly to the changing environment. Finally, learning transfer plans involve a systemic approach to aligning employee learning with performance at the individual, group, and organizational levels. Such strategies are benefitted by using design thinking (Plattner, Meinel, and Leifer, 2016) and scenario planning (Chermack, 2011).

DESIGN THINKING

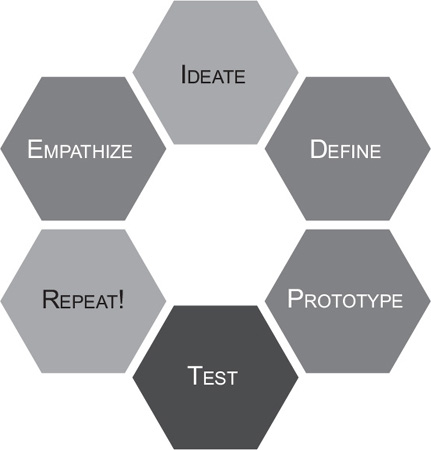

Design thinking is a solution-focused methodology for creative problem solving that ultimately supports planning (Neumeier, 2008). It can be used in a variety of HRD-related contexts (and can also be a helpful process for employees to utilize in a variety of situations). According to the Stanford d.school (2020), the steps used in design thinking include: (1) empathize; (2) define (the problem); (3) ideate; (4) prototype; and (5) test (figure 19.2). During the empathize stage, a design team led by HRD practitioners focuses on gaining an empathic understanding of the current situation. The focus is on key stakeholders related to the focal area of concern and can involve observation, engagement, and empathizing to understand perspectives of customers and internal-/external stake-holder perspectives. During the define stage, the HRD design team puts together information gathered from the empathize stage to define the identified problem(s). The define stage will help with the HRD-related design in collaboration with stakeholders and/or customers to establish elements that will allow them to solve the problem(s) identified. During the ideate stage of the design thinking process, HRD practitioners facilitate thinking-outside-of-the-box Processes that support the generation of new problem solutions. The next step involves prototyping in which the HRD-related interventions or new approaches are formulated at a scaled-down level (e.g., a pilot training, learning module, intervention scenario, technology solution, or customer-centered model or approach). Finally, HRD practitioners would test to evaluate the outcomes. If it is a training solution, they evaluate at multiple levels, including learning and performance outcomes. If it is an organizational redesign solution, they may use town halls or other large-space meeting techniques to test their ideas and assumptions. As an iterative process (repeat), the test stage can lead to adjustments that better address the identified problem(s) and an eventual reengagement of the process. In addition to receiving considerable attention from design-thinking-oriented consulting companies like IDEO (https://www.ideo.com), research results support design thinking as an impactful practice with HRD-related benefits coming both from within HRD applications and HRD-facilitated opportunities (Plattner, Meinel, and Leifer, 2016).

Figure 19.2: Stanford d.School Design Thinking Model

Scenario planning, a formal strategic planning technique, is an envisioned succession of future events that can be used to determine perspectives about possible changes that can be anticipated and possible organizational responses (see chapter 17). Organizational leaders and/or an organizational cross-section articulate plausible stories of external changes that are likely to impact their current state and aims to increase understanding of the possible situation that may occur in the future (Bushe and Marshak, 2009). Central to these considerations is the dialogic development of reactions to these plausible stories regarding the potential directions the organization may go regarding HRD requirements and how best to prepare the workforce. Scenario stories can then be aligned into the overall “strategic organizational planning model” (Swanson, Lynham et al., 1998).

Such scenario building can also be situated within broader process perspectives, such as appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider, 1995) or dialogic organization development (Bushe and Marshak, 2015). Both design thinking and scenario planning require extensive investment on the part of the organization in terms of executive, managerial, and key stakeholder time. But when faced with the alternative of neither engaging in needed design changes nor formulating possible responses to the future, HRD and organizational leaders often choose proactive solutions like these that lead to beneficial HRD policy and planning. Such in-depth engagement in HRD policy and planning have the potential to extend organization-wide planning capacities. Finally, one key element of design thinking and scenario planning is the important learning that can occur for engaged teams and organizations. While these processes are rarely perfect, the learning that occurs through ongoing discussions about possible futures for an organization, team, or even process can have a meaningful long-term impact.

HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Ultimately, HRD policy and planning must be tied to implementation, and the use of project management strategies and tools is important in supporting HRD. While overseeing HRD policy and planning, HRD leaders can fall short and “fail to provide a practical approach and techniques to planning and managing projects” (Gilley, Eggland and Gilley, 2002, 231). According to McLean (2006), the establishment of effective project management is essential throughout HRD implementation. Increasingly, all organizational work has been framed as a set and/or series of interrelated projects (Packendorff, 1995), making project management an essential HRD competency (Carden and Egan, 2008).

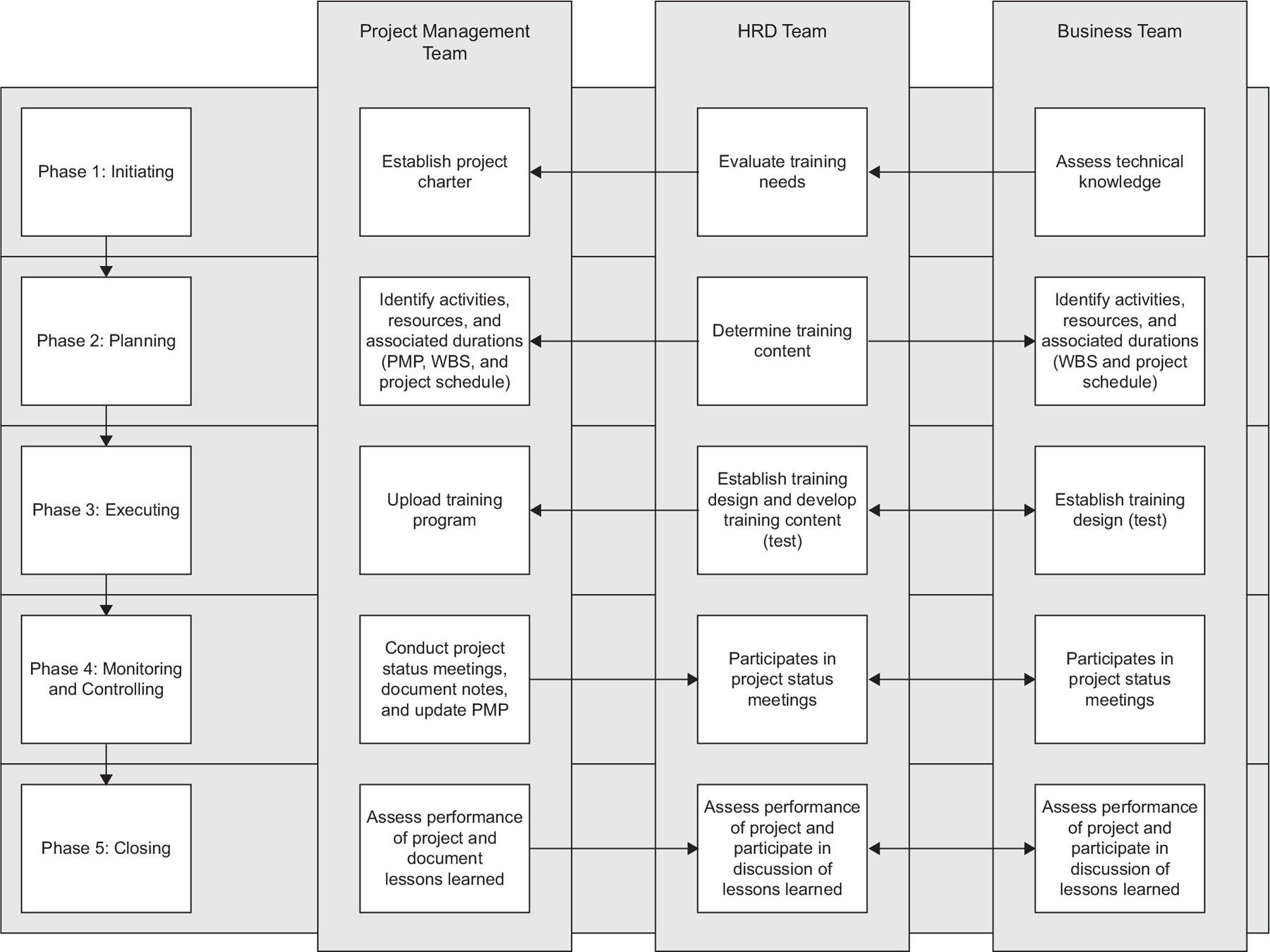

Project management is “the art of directing and coordinating human and material resources throughout the life of the project by using modern management techniques to achieve predetermined objectives of scope, cost, time, quality and participant satisfaction” (PMI Standards Committee, 1987, 4-1). Organizations such as PMI provide frameworks that can be used to implement planned HRD programs and interventions (figure 19.3). The most common PMI framework involves the five-phase project life cycle—initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing—can be found in PMI’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK).

Effective HRD project management includes appropriate deployment of HRD teams; tracking financial investment and related returns; maintaining effective contact with stakeholders; supporting HRD efforts by serving as an active liaison between operations, management, and HRD; and utilizing risk assessment modeling while anticipating options to address potential barriers. Without effective project management, HRD policy and planning will not be implemented with maximum impact. Pak, Carden, and Kovach (2016) provide a clear synthesizing framework involving the integration of project management, HRD, and business teams that is not only a solid model that can support planning-related deployment but can also be transferred to a variety of HRD contexts, from training and development to large-systems design. Extending the earlier example of HRD-related policy and planning in the training context, the Pak and colleagues Project Management, HRD and Business (PMHRDB) Partnership Model explicates an approach to synthesizing HRD with project management.

Key stakeholder teams with expertise in project management and HRD team up to align with a business team to focus on meeting an HRD-related planning goal aligned with a business unit. By combining these stakeholders (represented in the three vertical pillars) in the five-phase project life cycle process, the model was piloted in a U.S. corporation and found to be successful at achieving key training design, development, and implementation goals tied to the organization’s HRD policy and planning (Pak et al., 2016). Ideally, such a project management approach supporting planning and policy utilizing the PMHRDB model would become part of HRD policy and planning.

Conclusion

At its core, HRD policy and planning is about sustainable performance and accountability through the development of a resilient workforce. HRD policy and planning is best when clearly aligned with overarching strategic goals and in collaboration with governance and management teams. When well executed, HRD policy and planning is established as an essential part of large system or organizational growth and impact.

Figure 19.3: Project Management, HRD, and Business (PMHRDB) Partnership Model

Reflection Questions

1. Identify one concept related to HRD policy and planning that is most interesting to you and explain why.

2. Explain why policy is important for HRD.

3. Elaborate on two of the most interesting United Nations Millennium Development Goals. Why did you choose these?

4. Describe an example of how HRD policy and practice are connected.

5. Describe how cross-functional project management could be an advantage for HRD planning.

Internet Resources. Instructional support materials for this chapter can be found on this website: www.texbookresources.net