4

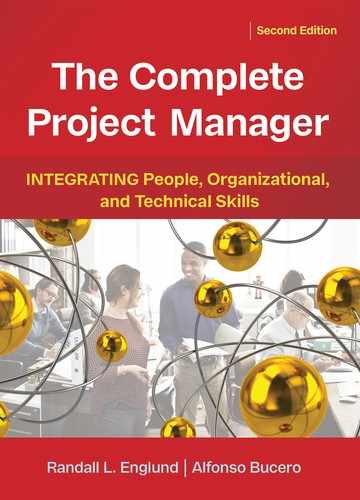

Political Skills

I’ve always said that in politics, your enemies can’t hurt you, but your friends will kill you.

—Ann Richards

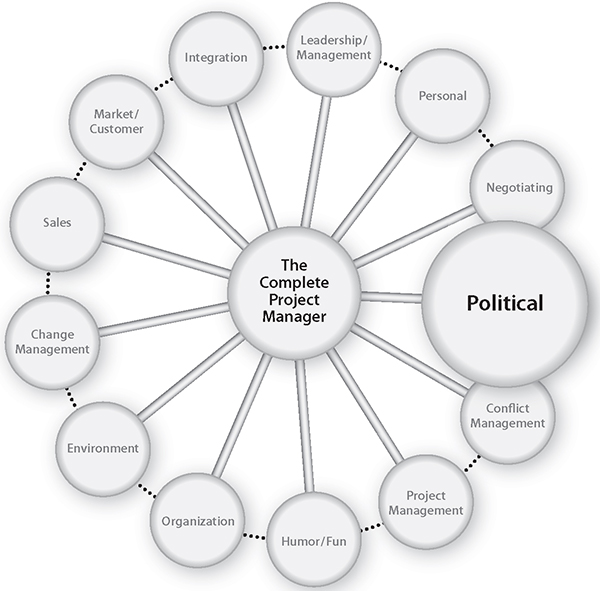

With developing skills in leadership, influence, and negotiating, we can in this chapter now address how to optimize project results in politically charged environments. A political environment is the power structure, formal and informal, in an organization. It is how things get done, within day-to-day processes and through a network of relationships.

Organizational politics is often viewed as the pursuit of individual agendas and self-interest in an organization without regard to their effect on the organization’s efforts to achieve its goals. Linking power and politics means individuals pursue an agenda to achieve results within an organization. Since project management is all about getting results, it stands to reason that power is required. Power is the ability to cause or prevent an action and make things happen. It is the capacity each individual possesses to translate intention into reality and sustain it. Organizational politics is the exercise or use of power.

Power is not imposed by boundaries. Power is earned, not demanded. Power can come from position in the organization, what a person knows, a network of relationships, and possibly from a particular situation, meaning a person could be placed in a situation that is a very important focus area within the organization. Leading with power in a project-based organization is about earning legitimacy in complex organizational settings.

Instead of lamenting a failed project, program, or initiative, strive to learn about power and politics to optimize project success. Knowledge, wisdom, and courage, combined with action, have the potential to change your approach to project work. The examples and insights shared in this chapter can help turn victim scenarios into win-win political victories.

The challenge is to create an environment of positive politics—that is, an organization in which people operate with a win-win (all parties gain) attitude. In this kind of organization, all actions are out in the open instead of hidden, below the table, or behind closed doors. People work hard toward a common good. Outcomes are desirable or at least acceptable to all parties concerned. Good, smart people, who trust each other (even if they do not always agree), getting together to solve clearly defined and important issues, guided by effective, facilitated processes, with full disclosure and all information out in the open, can accomplish almost anything. This is the view of power and politics we espouse in this chapter. The goal of improving your political skills is to create a more project-friendly organizational environment characterized by positive politics.

Recognize that organizations are inescapably political, so a commitment to positive politics is an essential attitude that creates a healthy, functional organization. This may be a change for the organization. In such an organization, relationships are win-win, people’s actual intentions are out in the open (not hidden or distorted), and trust is the basis for ethical transactions.

Develop Legitimacy

Influence exists in people’s hearts and minds, where power derives more from legitimacy than from authority. Greater ability to influence others comes from forming clear, convincing, and compelling arguments and communicating them through all appropriate means. These actions help create leadership legitimacy.

People confer legitimacy on their leaders. It is how they respond to a leader who is authentic and acts with integrity. Position power may command respect, but ultimately how a leader behaves is what gains wholehearted commitment from followers. Legitimacy is the real prize, for it completes the circle. When people accept and legitimize the power of a leader, they are more supportive of (and thus less resistant to) the leader’s initiatives.

BUILD A GUIDING COALITION

A common theme in the success or failure of any organizational initiative is building a guiding coalition—a bonding of sponsors and influential people who support the project or initiative. This support, or the lack thereof, represents a powerful force either toward or away from the goal. Gaining support makes the difference between whether or not the goal is achieved. Moderate success may occur without widespread political support, but continuing, long-term business impact requires alignment of power factors within the organization.

Organizations attempting projects across functions, businesses, and geographies increasingly encounter complexities that threaten their success. A common response is to set up control systems—reports, measures, and rewards—that inhibit the very results intended. This happens when we violate natural laws, inhibit free flow of information, and impose unnecessary constraints. These external forces tend to drive out whatever motivation is naturally present within people.

In contrast, taming the chaos and managing complexity are possible when stakeholders establish a strong sense of purpose, develop shared vision and values, share information as an enabling factor, and adopt patterns that promote cooperation across cultural boundaries. These processes represent major change for many organizations.

A complete project manager uses commitments to manage processes, projects, and work across units and geographic locations. Standard workflows and information flows that cut horizontally across organizations are missing the people perspective. A commitments-based approach fills the gap. Breakdowns occur when people do not make straightforward, clear requests or commitments to perform work, do not agree on “what by whens,” or do not designate responsibility for work elements. The point is that work actually gets done through conversations—by people making offers, requests, and promises to each other.

Too late, people often learn the power of a non-guiding coalition—when across-the-board support is not lined up or in agreement on a plan of action. For example, a project manager may be surprised by an attack from an unsuspected stakeholder, resulting in a resource getting pulled, the imposition of a new requirement, reassignment of a project manager, or the cancellation of a project. Getting explicit commitments up front, the more public the better, is important to implementing any project or initiative. It also takes follow-through to maintain the commitment. But if commitment was not obtained initially, it is difficult to maintain continuity throughout the life cycle of a project. It all starts by investigating attitudes and assessing how things get done.

ACKNOWLEDGE THAT POLITICS IS EVER-PRESENT

Albert Einstein said, “Politics is more difficult than physics.” Politics is present any time an attempt is made to turn a vision for change into reality. It is a fact of life, not a dirty word that should be stamped out. Instead of acknowledging this, however, we often think first of political environments in which people are sneaky or underhanded and that lead to win-lose situations. In these organizations, secret discussions are more prevalent than public ones. Reciprocal agreements are made to benefit individuals rather than organizations. People feel manipulated.

But project managers who shy away from power and politics are not being all they can be. An automatic negative reaction to the word “political” could be a barrier to success. Project managers should instead strive to operate effectively in a political environment.

Jeffrey K. Pinto, PhD, chair and professor in management of technology in the Black School of Business at Penn State Erie, two-time recipient of a Distinguished Contribution Award from the Project Management Institute, and author of Power and Politics in Project Management (1996), shared with us how he learned a political lesson:

Early in my career, I had the opportunity to learn from experience (how else does anyone learn these lessons?) the importance of political awareness for successful project managers. Our organization was undergoing a reduction in costs (shorthand for “downsizing”), and one Monday morning I was called, along with a peer, into our boss’s office and informed that the projects we were each overseeing were going to be evaluated that Friday afternoon. One of them would be cut from the budget, and the meeting was intended to give us each a chance to make our best pitch for retaining our project.

(Much of what happened next I was to discover over time and as a result of subsequent investigation.)

I left the office with my peer, both of us making sympathetic noises about how unfair the process was and how much work we needed to do to prepare our cases for retention. After I returned to my office, the peer made a quick U-turn and headed back for the boss. “Who is on the committee evaluating our projects?” he asked. When he was told, he spent the next three days negotiating, making deals, offering favors, calling in favors, and generally working on the members of the committee one at a time. By Thursday, he had lined up enough votes to ensure he would win.

Well, I walked into the meeting with flip charts, reports, pie charts, projections, and all sorts of supporting material. He walked in with a few notes he had scratched on the back of an envelope. My presentation was twenty-five minutes of facts, logic, figures, and everything needed to build a solid case. His presentation lasted five minutes, tops. At the end of the meeting, the outcome happened as expected by everyone except me—he got to keep his project and mine was cancelled.

I came to realize that this was a perfect example of a classic dictum of office politics: “All important decisions are made before the meeting takes place!” If we accept the idea that politics is simply enacted power, my peer was not doing anything “wrong,” per se. He just recognized this fundamental reality. For project managers, politics is a necessary device. It does not have to be a deliberately destructive process, but it recognizes that project managers are often without formal authority in their companies. As such, they are left with few options for improving the chances of project success. One important option is to learn how to use politics appropriately and persuasively. It can take you a lot farther than simply being technically competent or intelligent because it recognizes how much else is needed to bring a project to successful completion. As the Chinese proverb goes, “The smart man knows everything; the wise man knows everyone.”

Develop a Political Plan

ASSESSING THE POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT

Complete project managers understand the power structure in their organizations. Clues to a power structure may come from an organizational chart, but how things get done goes far beyond that. A view from outer space would not show the lines that separate countries or organizations or functional areas or political boundaries. The lines are manmade figments that exist in our minds or on paper but not in reality.

People have always used organizations to amplify human power. Art Kleiner (2003) premises that in every organization there is a core group of key people—the “people who really matter”—and the organization continually acts to fulfill the perceived needs and priorities of this group.

Kleiner suggests numerous ways to determine who these powerful people are. People who have power are at the center of the organization’s informal network. They are symbolic representatives of the organization’s direction. They got this way because of their position, their rank, their ability to hire and fire others. Maybe they control a key bottleneck or belong to a particular influential subculture. They may have personal charisma or integrity. These people take a visible stand on behalf of the organization’s principles and engender a level of mutual respect. They dedicate themselves as leaders to the organization’s ultimate best interests and set the organization’s direction. As they think or act or convey an attitude, so does the rest of the organization. Their characteristics and principles convey what an organization stands for. These are key people who, when open to change, can influence an organization to move in new directions or, when not open to change, keep it the same.

Another way to recognize key people is to look for decision makers in the mainstream business of the organization. They may be aligned with the headquarters culture, be of the dominant ethnicity or gender within the organization, speak the native language, or be part of the founding family. Some questions to ask about people in the organization are: Whose interests did we consider in making a decision? Who gets things done? Who could stop something from happening? Who are the “heroes”?

A simple test for where power and influence reside is to observe who people talk to or go to with questions or for advice. Whose desk do people meet at? Who has a long string of voice or email messages? Whose calendar is hard to get into?

RELATIONSHIP BUILDING, CREDIBILITY, AND COMPETENCE

One of the most reliable sources of power when working across organizations is the credibility a person builds through a network of relationships. It is necessary to have credibility before a person can attract team members, especially the best people, who are usually busy and have many other things competing for their time. People more easily align with someone who has the power of knowledge credibility. Credibility comes from relationship building in a political environment. Competence is also required.

In contrast, credibility gaps occur when a person previously did not fulfill expectations or when his or her perceived abilities to perform are unknown and therefore questionable. Organizational memory has a lingering effect—people long remember what happened before, especially when things went badly, and do not give up these perceptions without due cause.

Power and politics in relations across functional areas impact the basic priority of project management’s triple constraints—outcome, schedule, and cost. If the power in an organization resides in marketing, where trade shows rule new-product introductions, meeting market window schedules becomes most important. An R&D-driven organization tends to focus on features and new technology, often at the expense of schedule and cost.

After assessing the political environment and relationships within the organization, it then becomes necessary to decide what you can and want to do in your current situation. J. Davidson Frame, PhD, PMP, is a personal friend and mentor. He has such distinguished credentials as academic dean of the University of Management and Technology in Arlington, Virginia; Fellow and board member for the Project Management Institute; and noted author. David shares this story:

My exposure to astonishingly capable people early in life taught me a lesson that became important to me as I began a thirty-plus-year career in project management. I learned that one of the strongest categories of authority project employees can accrue is what I call the authority of competence. In standard project management courses and texts, we often encounter discussions of the importance of formal authority, referent authority, technical authority, and authority based on budget control. In my courses and project management practice, I devote special attention to the authority of competence. The basic premise is that if you are truly good at what you do—and if you work in a healthy organization—people will often defer to your insights and suggestions because they know your opinions have value. Who cares what sloppy performers think? Let’s listen to our most capable colleagues.

Your competence is your sword and shield. Even when politics raises its head in an organization, highly competent people can often stand above the fray. Who dares harm the goose that lays the golden eggs?

The big caveat to these points is that they only hold in healthy organizations. Organizations suffering from major pathologies—for example, politically mired organizations—are not likely to cherish competence. When project staff find themselves working in pathological environments, they cannot count on their competence helping them. They should leave as quickly as possible so as to avoid contagion.

My advice to project staff who want to grow their authority in their organizations: Work hard. Maintain the highest standards. Do whatever it takes to be excellent. Then enjoy the respect of your colleagues.

STAKEHOLDER BEHAVIOR

Stakeholder analysis is integral to developing a political plan. One fun way to do this is to apply traits or characteristics of animals to people within the organization. This is proven to be a less risky approach to sensitive topics, and people quickly come to understand the challenges of dealing with these “animals.”

For example, assess each individual with regard to the degree of mutual trust and agreement on the project or program’s purpose, vision, and mission. Then start a stakeholder management strategy by reinforcing positions of strength and working on areas of concern. Use the knowledge about traits and behavior patterns to address each stakeholder’s needs—and to protect yourself when necessary. Realize that different kinds of “animals” speak different languages, so the complete project manager needs to become multilingual, meaning that you adapt your language to whatever is most comfortable and customary for the person with whom you are speaking.

THE POLITICAL JUNGLE

One element of a political plan that can help create win-win political victories is assessing and negotiating the political landscape. An organic approach to project management means observing the world we live in and using or applying natural systems to organizational challenges. Especially when implementing any change in organizations, resistance arises. This resistance can be likened to someone new entering the political “jungle.” Resident animals react to this invasion in different ways, most often by attacking the invader. These reactions can be noted and then used to guide the interloper to act in ways that will ensure his or her survival and enable the creation of something new.

Within any organization, there are people whose traits and behaviors are similar to those of several jungle species. Solitary tigers live and hunt in forests alone. To survive, tigers require large areas with forest cover, water, and suitable large prey. A typical predatory sequence includes a slow, silent stalk, followed by a lightning-fast rush to capture the prey, then killing it with a bite to the neck or throat. A tiger must kill about once per week but is successful only once in ten to twenty hunts (Lumpkin 1998).

Male tigers’ territories are always larger than those of females. A female tiger knows the other females whose territories abut hers. Females know their overlapping males and know when a new male takes over. All tigers can identify passing strangers. Solitary tigers actually have a rich social life; they just prefer to socialize from a distance. The risk of mortality is high even for territorial adult tigers, especially for males, who must defend their territories from other males (Lumpkin 1998).

An astute project leader identifies the tigers in her organization. Those that rule over a large territory are C-level—chief executive, -operating, -information, or -project officers. They may also be general managers or possibly in the human resources department. They are strong and skillful empire builders. They are solitary because of the unique nature of their position; they wield the most power but are often isolated. This happens because other people fear the repercussions of telling them the whole truth or giving them all available information. A tiger’s environment is often very political and tenuous because many other people aspire to take over this territory and reap its benefits.

In contrast, lions are the most social of cats; both males and females form cooperative groups. Females live in prides of related individuals, and males form coalitions that then enter prides. Both sexes show extensive cooperation in territorial defense, hunting, and cub rearing. Prides compete with each other in territorial disputes. Males leave prides when they become mature or when a new coalition moves in. Male lions wander far and wide in search of food and companions until they are old enough and join a large enough coalition to take over a pride and become resident. Number of offspring depends on ability to gain and maintain access to a pride. Coalitions are usually evicted by a larger rival coalition, and once they have been evicted, they are rarely able to become resident in a pride again. Competition for residence in a pride can be very intense, with larger groups dominating smaller ones in aggressive encounters. A male coalition rarely holds onto a pride longer than two to three years before being run off by fierce challengers. The best predictor of a lion’s success is the size of his coalition (Grinnell 1997).

Both male and female lions roar. Resident males only roar when on their own territory—roaring by males is a display of ownership. Lion grouping was traditionally explained by the advantages of cooperative hunting. Groups of two or more females are far better at defending their cubs. Females minimize risk by moving away from the roars of strange males and avoiding new males. By banding together, females are better able to defend their cubs from direct encounters with infanticidal males, and by roaring together they minimize the chance that these encounters will occur at all (Grinnell 1997).

Lions discovered there are easier ways to keep intruders out than fighting everyone—roaring can be heard for miles, proclaims the caller as a territory owner, and informs the listener of the caller’s sex and location. However, in humans, spoken intentions are notoriously unreliable—it is easy to lie with words and tone of voice or vocal signals. Vocal signals are too easily falsified, and there is nothing to guarantee their honesty. Assessment signals, on the other hand, tell something about an individual that cannot be faked. They demonstrate how capable persons or groups really are. Members of a lion coalition often roar in group choruses that make it obvious they are roaring together and not in competition with each other. A group chorus cannot be imitated by an individual or a smaller group or produced accidentally by roaring competitors. A resident male keeps his declaration of ownership and intent to defend the pride honest by consistently challenging any intruder that disregards his roar. Resident lions roar, and nomadic males make their way silently around them (Grinnell 1997).

The lions in organizations are often functional managers and in marketing and sales. These people are outgoing, approachable, want things their way, and are driven by clarity and a single-minded purpose. They protect their boundaries and develop multiple relationships; they are visible, strong, and skilled. Their “roars” are heard across the organization as assessment signals that directly relate to the quality in question—they are low cost to produce honestly while costly to produce dishonestly. These signals are inherently reliable, because producing the signal requires possessing the indicated quality. For example, a marketing functional manager who berates the feature set of a new product under development needs to be taken seriously because this person usually possesses the clout to drive changes into the project plan.

Brown bears are solitary animals, except for females with cubs. They are territorial, with males having larger territories that overlap the smaller territories of several females. Bears leave territorial signposts—scent marking and long claw marks in tree bark. Brown bears occupy areas with extremely abundant food sources.

Although they are one of the most feared animals in the world, brown bears are usually peaceful creatures and actually go out of their way to avoid people. They prefer to roam in areas undisturbed by people and will flee as soon as they detect humans. (Brown bear populations cannot easily recover from losses because they breed slowly.) Although it usually lopes along, a brown bear can charge surprisingly fast if threatened—up to 30 mph, uphill, downhill, or on level ground, for short stretches (Youth 1999).

The bear strikes a chord of fear and caution, as well as curiosity and fascination: we think of them as wily, smart, strong, agile, and independent. In fact, bears are among the most intelligent of mammals. They have very good memories, particularly long-term memory, and they are excellent navigators.

Bears are usually silent. However, they make a variety of grunts when relaxed, and when frightened, they clack their teeth or make loud blowing noises. They can express a range of emotions from pleasure to fear.

If you encounter a bear, do not panic, run, or yell. Instead, act calm, stand your ground, look at the bear, and talk softly to it. Most bears will leave of their own accord after determining that you are not a threat. Bears read body language, so it is important to maintain as much composure as possible.

People working at remote sites and technical professionals tend to be bear people. Bear people have a deep introspective capacity and are caring, compassionate, seekers of deeper self-knowledge, dreamers at times, and helpers. They have tremendous power and physical strength, intelligence, inner confidence, reserve, and detachment. When in conflict, they retreat into the cave, draw great strength from solitude, choose peace instead of conflict, and contemplate their healing power. Their contribution is strength, introspection, and self-knowledge. Bear people can sometimes be too quick to anger and too sure of their own power. They have little to fear and can forget to be cautious. Being unaware of their limits in certain settings can be disastrous.

Leading with power in a political jungle starts with identifying, naming, and characterizing the animals that occupy the territory. People can be likened to other kinds of animals in addition to these. You can gather more ideas from team or group exercises in which people describe themselves or others as particular kinds of animals. This important step helps predict people’s resistance to changes in the status quo.

I (Englund) was very pleasantly surprised after presenting the above concepts at a PMI congress by the reaction from a favorite editor and colleague, Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, who writes for the business press on behalf of the Center for Business Practices, the publishing and research division of PM Solutions:

It’s a jungle out there where the consultants prowl.

I was reminded of this in Anaheim (across the street from Disneyland, appropriately enough), where I checked out a presentation by one of my favorite project management people, Randy Englund. I figured he’d have something fresh and different to say, unlike 80 percent of the project-management-presenting herd. Talk about an understatement. I had my first (well, only) belly-laugh of the conference when he opened his presentation on “Leading with Power,” with the deadpan explanation that the word “politics” comes to us from the Latin, “Poly, meaning many; plusics, meaning bloodsucking parasites.”

When he later invited us to identify the political animals in our workplace according to whether they were lions, tigers, or bears, I was surprised when the audience didn’t chorus “Oh my!” Maybe that was because there were so many attendees from outside the U.S. who didn’t grow up with Dorothy and Toto on TV. Or maybe project managers are too inhibited for call-and-response comedy. But I bet I wasn’t the only one who wondered when the flying monkeys were going to come on the scene.

Seriously, though, the metaphor of the political jungle can be a useful one for the person entering that jungle—er, organization. Which of the political animals are friendly? Tamable? Shy and in need of coaxing? Liable to eat you alive?

Those C-level tigers—the top cats whose territory spans the organization—have a weakness: because they are so solitary, they are isolated. It’s a struggle to remain at the top of the heap: the tiger inspires envy from the other tigers who would rule his territory, and fear from everyone else. Isolation and fear mean they often don’t get full or clear information. They operate—as tigers do—“in the dark.” Maybe that’s why their actions often seem so predatory and antithetical to the idea of organizational community.

Lions, on the other hand, like to bask in the sun with their large pride of admirers and hangers-on. You can hear them roaring a mile away. They defend their turf and serve a valuable function, keeping the herds on their toes and thinned out. Sound like any functional managers you know—especially, perhaps, those in marketing, sales, or human resources?

Meanwhile, the solitary bears go about their business quietly. Don’t bother them and they won’t bother you. They dislike people and avoid them whenever possible. They have an air of preoccupied introspection. But watch out if they think you are likely to cause harm to one of their “babies.” Technical people—and writers!—can identify with the image of the bear. Don’t let that slow, ambling pace fool you: the bear’s sharp intelligence is very busy and quick. And those claws can be sharp when need be.

Why do we feel vaguely guilty when we start having fun in a work-related setting? Must be our Calvinist forebears. (No pun intended.) I noticed that the complement of attendees of Indian extraction had no trouble entering into the metaphor and playing along.

Play and metaphor aren’t a distraction from thinking about organizational life, but a refreshing and productive new angle. In the past few years, there have been quite a few books and papers written about the uses of metaphor, storytelling, and fun in building positive organizational culture and helping people deal with the stressors of organizational change. Randy wasn’t just fooling around when he included this segment in his paper: he was providing an object lesson in how we can begin to regard organizational politics in a positive light. Instead of politics being the realm of win-lose, covert and manipulative action, he suggested we confront the reality of “the jungle” and engage with it, striving to create a political playing ground of win-win, openness, and desirable outcomes.

Hmmm. Sounds like that wouldn’t be a bad idea in national politics, as well as in the organizational variety.

But—I’m still stuck on those missing flying monkeys. Who are they? Well, they’re the screamers; the shock troops; the attack machine. They display mindless, groupthink obedience to evil authority. They swoop in and carry their prey away. When you figure out where they fit in the organizational chart, let me know. (Cabanis-Brewin 2004)

The next task for the project leader is to apply political savvy within her environment. Difficult challenges do not have simple answers but responding in an authentic way and with integrity leads to effective action. These are fundamental concepts that get left out of modern busyness. You may be tempted or pressured to deliver short-term expedient responses. However, imagine yourself five years in the future looking back on this time. What will you be most proud of when faced with difficult political situations? What will you remember—that you met a budget or that you did the right thing? How you make people feel will be remembered longer than what you did or said.

A POLITICAL PLAN

Since organizations by their nature are political, complete project managers become politically sensitive, meaning that they become aware of how things get done in an organization but do not get dragged into negative political battles. Beware of ambivalence toward power and politics. Take a stand: work to motivate others to reach win-win solutions, out in the open. The alternative is to become a political victim of a win-lose situation that is conducted not in the open but in a metaphorical back room, out of sight of full disclosure. History is replete with scenarios where growth is limited or curtailed by dictators, mob controls, or special interests. Free markets and open organizations accomplish far more in shorter time periods.

Create a political plan that addresses the power structure in your organization, levels of stakeholder impact and support, who will form a supporting or guiding coalition to make the vision become reality, and the areas of focus that constitute a strategic plan. We present a template and Sample Political Plan in The Complete Project Manager’s Toolkit and online at www.englundpmc.com/offerings/.

Dealing with politics is like playing a chess game. While you are conscious of the role and power of each chess piece, success in the game depends upon your movements and the movements of your adversary. A good “chess player” can influence people in organizations.

IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN

I (Englund) worked with Dr. Ralf Müller to write an article on implementing a plan for addressing the political jungle, “Leading Change Towards Enterprise Project Management” (2004). An excerpt follows.

After identification of the political animals and the development of a political plan, it is time to use the animals’ power for support and development of project management in the organization. Successful approaches to move project management from a tactical “one-off” task to an enterprise-wide strategic asset for the organization often start on a small scale and then grow organically over time. By identifying a single individual, preferably one of the most experienced project managers who also possesses a rich dose of political sensitivity, the approach gains credibility in the eyes of those who will critically observe how project management moves forward. Similar to the brown bear, this individual has standing, introspection, and self-knowledge. Another similarity with the brown bear is that the person finds itself in an area of abundant food resources. All organizations have unsuccessful projects to rescue, skills and practices of existing project managers to improve, etc. The question that arises is, where to start?

Among all possible areas for improvement, an initial focus needs to be on organizational acceptance of the approach. The person in charge of moving project management forward has to build a reputation of being loyal, knowledgeable, and politically astute. In other words: a trustful person. That is best achieved by helping other project managers and line managers become successful with their projects. How is that done?

It is a three-step process, where the accomplishment of each step allows for a balance, or equilibrium, of investment in project management capabilities and possible returns for the investment through better project results. Depending on the importance of project work for an organization, it could remain at step 1 or move on to steps 2 and 3. If project work is only occasionally done, then step 1 would be enough. If project work is a major contributor to the organization’s results, then step 2 should be accomplished. If, however, projects are the building blocks of an organization’s business, then the achievement of step 3 is needed for sustained success in projects and economized return on investment (ROI). Achieving step 3 is more likely when political power is diffused, and high levels of trust are present. So, what are the three steps?

Step 1: Laying the foundation. This starts with an inventory. By assessing what the organization provides in the form of methodology and basic training, it is possible to identify what project managers could potentially do to manage their projects better. Similarly, by looking at steering group practices it is possible to identify what management demands from their project managers. That includes an assessment of management’s interest in good project management practices. Then what is really done in projects is identified through reviews, especially those of troubled projects.

Having insights in project management practices from these three perspectives allows for improving the practices so that they become synchronized. That means achieving harmony in what the training and methodology allows people to do, and in what their management demands from them, as well as in what is really done in projects. This is achieved through assessment of current practices and careful steering of project managers and line managers into a common direction, so that expectations about projects and their management practices become aligned among project team members, project managers, upper management, and customers. This establishes a common foundation for project management. It is equilibrium of investment and ROI at a low level. This foundation step may be sufficient for organizations where project work is only a minor part of their business and not intended to grow.

Step 2: Getting in the driver’s seat. Step 2 is a major step forward. It requires management commitment to project management as a driving force for business success. Companies whose business results are largely dependent on successful project delivery aim for this step. It typically follows a successful implementation of step 1. The individual(s) implementing the prior step now become institutionalized as an organization, a project management office (PMO), or a project office (PO). At this step a paradigm shift is needed. The bear-type persons who accomplished step 1 cannot take care of all projects and all project managers at the same time. Just as the lions described previously, they need to find cheaper ways of dealing with intruders (bad project results). So, the bears need to staff their PMO with a few lions who roar in concert, so that it can be heard throughout the entire organization. In organizations this means that project-related information is no longer constrained to a few (troubled) projects but becomes available as a summary report of all major projects on a monthly basis. This fosters communication across organizational hierarchies and establishes shared knowledge about performance on a project and organizational level. It institutionalizes “speaking truth to power” in the organization’s culture, which dramatically reduces project-related rumors and backstage politics.

In parallel, the PMO will establish an external “proof” of project management capabilities through certification. That serves several purposes. It shows that (a) the PMO aims for professionalism that goes beyond established internal project management practices, (b) the project management resources are skilled, credible, and acknowledged, and (c) project management and associated skills can be used as a sales argument in the company’s marketing efforts. This step requires another concerted roaring of the lions in the PMO. Convincing project managers to become certified is not an easy task. Especially the most experienced ones, who have not been back to school for a long time, are afraid to lose face by not passing the examination. This is counteracted by the PMO being a role model, having the first certified project managers and offering preparation courses for certification exams. While the lions in the PMO are busy with communicating messages about project results and need for certification, the bears take care of overall PMO management and strategically important projects. For that they mentor project managers in unusually complex projects, or test new techniques and tools for their usability in the organization.

Step 2 establishes breadth and depth in moving project management toward an enterprise-wide practice. While step 1 allowed developing the roots for enterprise-wide project management through working on a few projects, almost unnoticed by large parts of the organization, step 2 makes project management growing and visible to everyone. It balances efforts and returns for organizations whose business largely, but not entirely, depends on the successful management of projects.

Step 3: Take the lead. If projects and their management are the strategic building blocks of an organization’s business, then it is not sufficient to be just as good as the others—the competitors. Then an organization must strive to become the leader in its field. It requires a broadening of perspectives. Internally the organization needs to broaden its perspective on competencies to include not only project management and technology knowledge, but also industry skills and more advanced planning and management techniques. That is accomplished through advanced training programs and proven through internal certification programs (see also Müller 2002). As in step 2 above, this is a task for the lions in the PMO. Their concerted roar makes the need for deeper skills and broader certification heard throughout the firm.

The second perspective that needs to be widened is project management execution. That is achieved by benchmarking project management practices against companies from the same industry and from other industries. While the same industry benchmark gives an indication of where the organization can improve in respect to its competitors, other industry benchmarks give indications on where to improve to become better than the competitors. This requires the bears in the PMO. Their long-term experience and retrospection allows them to identify improvement areas that are adequate and possible.

The third perspective that needs to be broadened is that of the organization and its responsibility for managing projects. Develop an understanding that all work in the organization has to support proper project management, because that is the cornerstone of business results. By building awareness that all organizational entities ultimately thrive through successful projects, a large number of processes, accountabilities, and authorities get prepared to change, and functional silos get converted to cross-organizational decision-making teams.

Reaching this stage requires another species of PMO member. It is the eagle who hovers above the organization and sees the big picture and how all pieces of the organizational puzzle fit together. In the next moment, the eagle is able to work on a granular detail level to fix processes, roles, and responsibilities. The eagle’s tools are organizational project management maturity models, which can range from simple five-step models that give a one-dimensional “level of maturity” stamp to complex multidimensional tools that profile organizational maturity and help to identify areas to improve. Organizations applying the techniques outlined in step 3 are on the path to become leaders in their field and a reference point for project management in their industry. They develop project management into a strategic asset of their firm, with the PMO as the focal point of all activities. That shifts PMO responsibilities from improving single projects (step 1) via improving project management professionalism (step 2) toward building the project-based organization (step 3).

Organizations following these steps also develop program and portfolio management capabilities in parallel. Here programs are understood as groups of projects that serve a common objective and portfolios as groups of projects that share the same resources (Turner and Müller 2003). The PMO’s role in steering project management positions is uniquely to take on portfolio management roles, such as the management of portfolio results through project selection, as well as business and resource planning prior to projects entering the portfolio, followed by identification and recovery of troubled projects, steering group management, and practice improvement, once projects have entered the portfolio (Blomquist and Müller 2004).

Throughout the journey to enterprise project management, the power and authority of the PMO increases tremendously. Along this journey, the PMO engages in the political power-plays of the organization by aligning its own strengths and weaknesses with those already in power in the organization. Here it is recommended to align bears with bears—those with deep insight in practices, relationships, and political games. Similarly, the lions from the PMO could make themselves even better heard if they align their voices with the lions from other organizations. As described by Englund (2004), making the steps and changes “stick” to survive the test of time (and reorganizations) falls under the purview of a strategic project office (SPO). Invoke the power of the tiger (CEO) to successfully establish an SPO. Along the way, the eagles need to find their counterparts. Eagles are rare, as most bears and lions prefer to stay as they are, and there is little hope to develop them from within the PMO. However, eagles are often found at the CTO (chief technology officer) level or even outside the firm in professional organizations, consultants, or at universities. These internal and external voices can provide a significant weight to the PMO’s value-add in moving the firm toward its strategic objectives.

Looping Behaviors

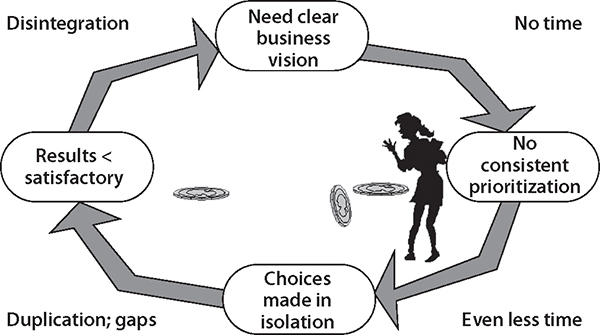

Causal loops, both vicious and virtuous, are a tool that helps depict the consequences of political behaviors. For example, it is easy to get caught in a vicious loop when there is no time to create a clear and widely understood business vision—daily actions consist of problem solving and firefighting, often more driven by urgency than importance. Consequently, there is no consistent prioritization of work, and a vast diversity of “stuff” then happens, which leaves even less time to prioritize.

Choices are made in isolation, which creates duplication of effort or gaps in the product line. This leads to unsatisfactory business results, because the important things do not get done. We then come full circle around the loop: we need a clear business vision. The trick is to break the loop somewhere—almost anywhere is fine when you understand how these loops work.

Leaders, caught up in a vicious loop similar to Figure 4-1, who also act without authenticity and commit integrity crimes (see the list below), follow a “shifting the burden” archetype. This means they get caught up in shallow or safe steps instead of addressing fundamental solutions required by people in the organization to improve their effectiveness. Leaders can choose to ignore fundamental values—but they will find themselves in a difficult predicament. Or else they can tap the energy and loyalty of others to succeed. The difference resides in whether they transparently act with authenticity and integrity.

Figure 4-1: A Vicious Loop

EXAMPLES OF INTEGRITY CRIMES

• A manager giving a pep talk to the project team on the (unrealistic) “merits” of doing an eighteen-month project in six months

• Starting a meeting with a stated intention but diverting it for your own purposes

• Passing along senior management’s statements to the rank and file as if you agree, even when you do not

• Ending every telephone conversation by saying “Someone’s at my desk, so I have to go now”

• Requiring weekly milestones to be met, promising feedback and customer reviews but not providing them

• Directing people to use a standard methodology but not training them on it

• Promising to send a contract the following week—then not sending it

These actions make people feel violated.

AUTHENTIC LEADERSHIP IN ACTION

A fundamental solution within the process of creating a political plan includes applying tools of influence, being authentic, and acting with integrity. People who are authentic believe what they say, and people with integrity do what they say they will do, and for the reasons they stated to begin with. Authenticity and integrity link the head and the heart, the words and the action; they separate belief from disbelief and often make the difference between success and failure.

Many people in organizations lament that their “leaders” lack authenticity and integrity. When that feeling is prevalent, trust cannot develop, and optimal results are difficult if not impossible to achieve (Englund and Graham 2019, 9). It becomes painfully evident when team members sense a disconnect between what they and their leaders believe is important. Energy levels drop, and productive work either ceases or slows down.

Integrity is the most difficult—and the most important—value a leader can demonstrate. Integrity is revealed slowly, day by day, in word and deed. Actions that compromise a leader’s integrity often have swift and profound repercussions. Every leader is in the spotlight of those they lead. As a result, shortcomings in integrity are readily apparent. Political leaders who “failed” often did so not by their deeds but because they lacked integrity.

Managers who commit integrity crimes have become victims of the measurement and reward system. The axiom goes, “Show me how people are measured, and I’ll show you how they behave.” Measurement systems need to authentically reflect the values and guiding principles of the organization. Forced or misguided metrics and rewards do more harm than good.

People have inner voices that reflect values and beliefs that lead to authenticity and integrity, but they also experience external pressures to get results. The test of a true leader is balancing these internal and external pressures and demonstrating truthfulness so that all concerned come to believe in the direction chosen. Know that people generally will work any time with, and follow anywhere, a person who leads with authenticity and integrity. Be that person.

Remco Meisner adds these cautionary thoughts:

Not all people having influence on projects will be honest or transparent. Some will have other values than yourself, which for a project manager frequently will cause such folks to move about in mysterious ways. Maintain your own transparency. Tell others wholeheartedly what you are about to do, and why, and in what way. You only need to be able to explain your moves to your own project board. You might be able to do that while adjusting things slightly and, in that way, also keeping a good relation to those with alien values.

Many organizations lack good political “swimmers.” Leading with power is a learned skill. It involves assessment, identification, skill building, planning, and application. Like all learning, it involves movement between reflection and action. Creating a political plan starts with making a commitment to lead with power, most probably personal power. It continues by taking action to identify sources of power, perform stakeholder analysis, and apply the values of authenticity and integrity.

Look systematically at your organization’s political environment. If your environment can be depicted as a vicious loop, work to create a virtuous loop based upon tools of influence. Trust cannot develop, and efforts to implement enterprise project management remain unrealistic, until leaders create an environment that supports these values. Take the time to document a political plan, noting your observations and deciding upon action steps.

Speaking Truth to Power

In our book Project Sponsorship: Achieving Management Commitment for Project Success, Second Edition, we describe a case study about speaking truth to power. In essence, project managers are closest to the action and know the truth about what is happening (or not, and why). However, those in power (upper managers) are not always willing, able, or in a mindset to hear the truth. Any interruption in this dialogue can be devastating to achieving consistent successful projects. Complete project managers need to be skilled to communicate all news—good, bad, and ugly.

The steps in this process are:

1. Ask what’s bad about the news.

2. Define the truth.

3. Determine how to deliver the truth.

4. Act from strengths.

5. Get it done.

The goal is to live another day, not be the messenger of bad news who gets shot!

Ethics and Power

It is the responsibility of each leader and manager to behave in a professional manner and adhere to an ethical code. These behaviors build credibility in the leader as well as contribute to the legal, moral, social, and ethical health of the organization.

Michael O’Brochta, president of Zozer, Inc., has had a long and successful career working with government project managers. He writes in How to Get Executives to Act for Project Success (2018):

Having the ability to speak truth to power is an important skill. When effectively practiced, the project manager’s level of influence, relative to lack of authority, will increase. That influence will further increase if the project manager effectively communicates the value of successful projects.

To ramp project manager influence levels up even further, behave like an Alpha. A survey of over 5,000 project managers, stakeholders, and executives has provided an extraordinary insight into what the top 2 percent of project managers, the Alphas, know and do that everyone else does not. The Alphas believed strongly that they had enough authority, even though they had the same amount as others. They also spent twice as much time planning and were twice as effective with communication as the others. Furthermore, their communications were in the business context that resonated with executives.

Project managers can understand and use power. Power refers to the ability of the project manager to influence others to act for the benefit of his or her project; it is a resource that enables compliance or commitment from others. Project managers have an excellent opportunity to build levels of expert power (centered around what the project manager knows about his or her project), and levels of referent power (affiliations the project manager has with other groups and individuals). Keys to building these two types of power are ethics and trust. As former Chair of the PMI Ethics Member Advisory Group, I can confirm that one of the most effective ways to build trust is to abide by the four values in the PMI Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct: responsibility, respect, honesty, and fairness. Transgressions in any one of these four values can cause immediate and long-lasting undercutting of trust.

Yunive Moreno Sanchez, a project manager in Mexico, believes project management can help turn the tide of corruption occurring in her country. She is a project manager leading the implementation of an anticorruption initiative. The project aims to shed light on the process by which the municipal government issues building permits.

Guadalajara has grown rapidly in recent years, but some construction projects haven’t been properly reviewed; illegally issued building permits have been prevalent. But project managers with high ethical standards can make a difference by avoiding corruption in contracts and ensuring budgets are monitored property. “Project management principles let you promote an anticorruption environment and set clear rules and procedures to follow in order to have clean and successful project implementation,” says Sanchez.

Sanchez says she has faced resistance from the government while trying to implement change. She does have the support of the current mayor, which helps enact her change agenda. She’s made a point of engaging external stakeholders so that the project can continue after the next municipal administration takes office. “We are communicating the project to stakeholders all over the city to make them owners and part of the project,” she says. The goal is to leverage strong backing from the public and civil society organizations to counter any political resistance to change. “We want to assure the continuity of the project beyond any future political change” (PM Network 2018, 61).

Summary

Embracing a complete project management mindset goes beyond completing projects on time, scope, and budget. Improving organizational performance depends upon getting more accomplished through projects. Just what gets accomplished and how comes under the purview of power and politics. Because power is the capacity to translate intention into reality and sustain it, and organizational politics is the exercise or use of power, leading change toward enterprise project management means embracing the political environment as a means to achieve broader success.

Organizations by their nature are political. To be effective, project managers need to become politically sensitive. Assessing the environment, rethinking attitudes toward power and politics, and developing an effective political plan are foundation steps toward developing greater political sensitivity. These steps help the project manager address the power structure in an organization, identify critical levels of trust and agreement with stakeholders, develop a guiding coalition, and determine areas of focus. One key goal of developing political sensitivity is to turn potential victim scenarios into win-win political victories.

A political plan is an overlay to the project management process. This plan involves observing how an organization gets work done and performing stakeholder analysis. It further incorporates creative human dynamics to encourage proactive thinking about how to respond to and influence other people in the organization. Complete project managers develop political plans as well as effective project plans. The political process is always at work in organizations, and the political jungle is chaotic. Success comes to those who identify the “animals” in the jungle and recognize that they exhibit certain traits and patterns. Each is driven by a purpose. Interacting effectively with these “animals” and influencing them involves working in their preferred operating modes, speaking their language, and aligning common purposes.

Leading change in political environments is a learned skill. It involves assessment, identification, skill building, planning, and application. It also involves knowing the potential of project management and the willingness to apply a disciplined process to a web of simultaneous projects across the organization. Like all learning, being effective in this environment involves movement between reflection and action. Ethical behavior is mandatory.

Peak-performing people use potent processes, positive politics, and pragmatic power to achieve sufficient profit and keep organizations on a path toward a purpose. By applying these concepts to tough situations, project leaders become better equipped to implement change, develop skills that achieve greater impact, and advance project management maturity in their organizations.