6

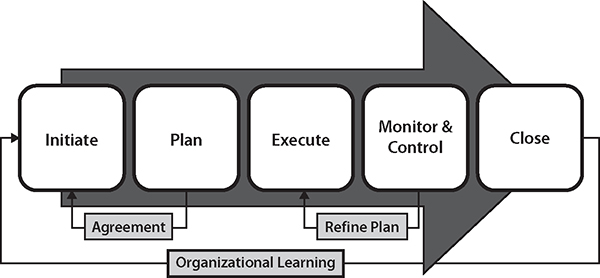

Project Management Skills

Excellence in project management is not a differentiator—it is an expectation.

—GREGORY BALESTRERO, FORMER CEO, PROJECT MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE

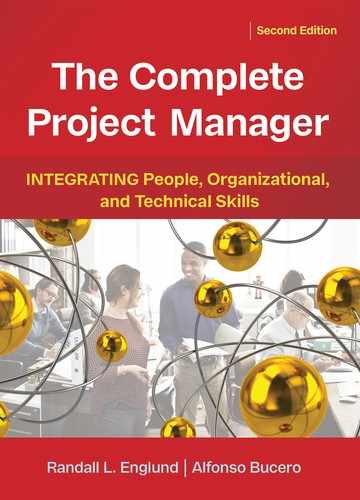

Figure 6-1: The Complete Project Management Process

In this chapter, we build upon a foundation in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, developed by the Project Management Institute. Our goal is to add insights and examples to help complete project managers in their quest to make sense of and apply the PMBOK Guide—exploring the rest of the story. We step through the stages of the project management process and share suggestions for implementing the process, focusing on people issues germane to a complete project manager mindset. We then offer a few words about creating project and organizational excellence, responsibility, and competencies. Guidance is offered about using appropriate methodologies, such as Agile.

Figure 6-1 displays the complete process. Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, and techniques to execute projects effectively and efficiently. The PMBOK Guide identifies the recurring elements: the five process groups of Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing, and the ten knowledge areas of Integration, Scope, Time, Cost, Quality, Procurement, Human Resources, Communications, Stakeholder Management, and Risk Management. While this guide provides a basic structure for projects, the rest of the story involves practice, ingenuity, and learning from others in order to achieve breakthrough performances. Let us start with initiating projects.

Initiating Projects

A common mistake is to focus on a benefit you are providing (an output) and not articulating the benefit of the benefit (the outcome—in other words, the value in business terms). Outputs are actual deliverables or products/services. Outcomes are the success criteria or a measurable result of successful completion of the outputs. Emphasis is often placed on collecting outputs, with little attention paid to outcomes. But outputs may have little intrinsic value unless they are linked to outcomes.

For example, a complete project manager might say, “By initiating a project office to coordinate our portfolio of projects [output], we select the right projects to meet our strategic goals and provide the key set of services required by our end users [outcome].”

THE PROBLEM STATEMENT

Unless project team members and departments see a need for solving the perceived problem or see an opportunity for innovation, it will be difficult to obtain the necessary resources for the project. A problem statement underscores the value to be gained for the organization by carrying out the project.

Every problem has causes and effects. In order to make a convincing argument that a project is required to solve a particular problem, it is beneficial to include the causes and effects of the problem in the definition. A problem statement answers the following questions:

• Why is this project necessary? What problem, situation, or need justifies the project?

• How do we know that the need exists?

• How is it currently handled?

• How does the problem affect productivity, teamwork, profitability, or other crucial factors?

• How will the project solve the problem or take advantage of the opportunity?

WHAT IS PROJECT SUCCESS?

The typical goal for leaders and managers is to achieve project success. Taking a high-level view of project success, identify the thread that runs through all key factors that determine success, failure. These factors are all about people. People do matter. Projects typically do not fail or succeed because of technical factors; they fail or succeed depending on how well people work together. When we lose sight of the importance of people issues, such as clarity of purpose, effective and efficient communications, and management support, then we are doomed to struggle. Engaged people find ways to work through all problems.

There is a bountiful harvest of definitions for project success (and just as many explanations for project failure). Meeting the triple constraints is just a starting point. Sometimes you can be right on scope, schedule, and resources and still fail to be successful, perhaps because the market changed, or a competitor outdid you, or a client changed its mind. You could also miss on all constraints but still have a successful project in the long term. It is important to get all requirements specified as accurately as possible; it is also important to be flexible since needs and conditions change over time or as more becomes known about the project as it progresses.

Please allow us to suggest an overarching criterion for project success: check with key stakeholders and ask them for their definitions of success. Pin them down to one key definition each. You may get some surprising replies like, “Don’t embarrass me.” “Keep out of the newspaper.” “Just get something finished.” You may even get conflicting responses. Integrate the replies and work to fulfill the stakeholders’ needs. Having this dialogue early in project life cycles provides clear marching orders—and forewarning about what is important to key stakeholders.

Having established that success or failure is all about people, our goal now is to be better leaders and managers of people, not just projects.

THE IMPORTANCE OF VISION

A vision statement is a vivid description of a desired future state once the project is successful. It is unique to that project, and stakeholders will know when that new state is realized.

To illustrate the power of clear vision in guiding initiation and directing project execution, we share this example from Dr. Thomas Juli of Germany, the author of Leadership Principles for Project Success (2010):

Working in professional project management for many years, I have worked on and managed numerous projects of all sizes. Not all of them could be considered successes. And this was good, for it taught me what matters most in ensuring project success. What I have found is that project management skills are necessary but not sufficient. Instead, effective project management needs to have a solid foundation in project and team leadership.

Now, not every project manager is a natural leader. And this is not necessary. But every project manager should know the basic leadership principles for project success. One of the most important principles is that a project leader helps build a common project vision. A project vision goes way beyond a formal project objective statement. A project vision constitutes the purpose of a project. It sets the overall picture of a project.

Building a common project vision is no academic exercise. It is pragmatic and can be relatively simple. To illustrate this point, let me tell you a story about a project that supports this claim.

My wife and I were deeply frustrated that there was no reliable preschool in our town. Our eldest daughter had just finished attending a preschool that, unfortunately, closed shortly after, and there was no other preschool in our community. This is why we were looking for a preschool for our youngest daughter. There were other preschools in the region. However, they were overpriced or had a waiting list of one year or longer. This was clearly no solution to our problem. One evening we met with other parents who faced a similar situation and were equally frustrated. We talked about what a relief it would be to have a reliable preschool in our town. We visualized the daily routines, the happy kids, you name it.

At one time I stopped the discussion and asked why we couldn’t found a preschool by ourselves. We had a vision of the preschool—saw its daily operations, the happy and smiling kids. We saw how happy we were. Soon our initial skepticism of founding and running a preschool was replaced by excitement and an entrepreneurial spirit. We had nothing to lose and everything to gain. One week later we met again and founded an organization as the legal prerequisite for the preschool to develop. Only nine months later we opened a preschool in our town. Six years later, the preschool is still operating and has expanded in size. It has become an institution in our community.

There were a number of reasons why this project turned out to be a huge success. The cornerstone of our success was our vision and our belief in it. The vision of founding and running our own reliable and affordable preschool drove our daily planning. In the beginning we did not have the faintest clue how exactly we could realize our vision. And there were a lot of obstacles ahead of us. People and other organizations told us that it would take at least two to three years to found a preschool. Well, we proved them wrong. Our vision carried us, helped overcome obstacles. Maybe our vision even caused us to overlook the obvious obstacles and master them without much hassle. We proved our critics wrong and accomplished the seemingly impossible in less than a year. This story illustrates that having the right vision can carry you a long way. The right vision defines the direction of your project. It constitutes the reason for initiating your project in the first place. It sets the tone of the overall project and what you want to achieve. It helps overcome obstacles because it is a driving force.

To get a handle on vision and how it comes to be a part of a good leader’s life, understand these points:

• Vision starts within. Vision comes from inside. Draw on your natural gifts and desires. Know yourself better; ask other people for feedback to get a fuller picture of your competencies and areas for improvement.

• Vision draws on your history. Vision grows from a leader’s past and the experiences of the people around him or her.

• Vision meets others’ needs. True vision is far-reaching.

• Vision helps you gather resources. The greater the vision, the more winners it has the potential to attract.

Where does vision come from? To find a vision that is indispensable to leadership, become a good listener. Listen to several voices:

• The inner voice. Do you know your life’s mission as a project manager?

• The unhappy voice. Discontent with the status quo is a great catalyst for vision.

• The successful voice. Nobody can accomplish great things alone. Fulfilling a big vision requires a good team. But you also need advice from someone who is ahead of you in the leadership journey. If you want to lead others to greatness, find a mentor. Do you have an advisor who can help sharpen your vision?

• The higher voice. Although it is true that your vision needs to come from within, do not let it be confined by limited capabilities.

Vision is essential to more than initiating projects for an organization. We manage many projects in our lives, and one of them is our professional development as project managers. Every project manager needs to manage her career as a project—or rather, like a program—which requires vision. Growing personally and professionally should be a project manager’s obligation. Such growth requires time, effort, passion, persistence, and patience. Work on your vision to build up your professional career. Without a clear vision, it will be difficult to achieve great things as a project manager.

Planning Projects

During the planning process, break down all tasks required, estimate task durations, assign an owner to each task, and assemble all tasks into a schedule. Take into account all learnings from previous projects about how long tasks take and about “unknown” tasks that mysteriously but always come up. Plan for these to appear in new projects as well.

It is always worthwhile to consider alternative ways to execute the project. This may not only resolve resource conflicts but may also allow you to complete the project earlier or use fewer resources than originally planned.

In all likelihood, the project plan will contain several resource overloads. A resource overload occurs whenever the project requires more than 100 percent of a resource’s available time in a given period. The process of resource leveling removes resource overloads and ensures that the project only requires up to 100 percent of a resource’s available time. The project plan remains unrealistic until all resource overloads have been leveled.

When two or more projects compete for resources, the organization needs to set strategic priorities. An agreed-upon and clearly communicated process for selecting projects and staffing them with necessary resources helps to depoliticize project management and make projects a more integral part of the business strategy. Although the project sponsor and steering committee are ultimately responsible for assigning scarce resources, it is important for the project leader to show the consequences of not obtaining necessary resources to the project’s deadline or quality. Involve the project steering committee or project sponsor in the decision-making process.

Do an analysis of all key people who have a stake in the project to:

• Understand their needs

• Establish accountability and performance expectations

• Recognize issues and concerns

• Identify preferred communication processes

• Mitigate potential conflicts

• Develop collaboration mindsets

Analyzing stakeholders and talking to them is a key activity in the planning phase of a project. When I (Bucero) started as a PMI chapter president, my chapter had no membership activities. I proposed to my chapter’s board of directors that we organize a professional PM event. They agreed and committed as a team to do it. I thought that a professional event would be well accepted, but I made a mistake. My team and I planned the event without asking the members what type of event they wanted. The event was successful, probably because we delivered the event content very passionately. At the end of the event, we ran a survey, and it was then that we discovered our main stakeholders’ real needs. Now I generally spend time asking questions of stakeholders. They often express tremendous gratitude for my efforts to explore their interests.

Stakeholder analysis helps project managers understand how different individuals can influence decision making throughout the project. A sample stakeholder and matrix worksheet is available at www.englundpmc.com, under “Offerings.” You can use it to conduct an initial stakeholder assessment. The resulting graph depicts the level of interest and power of each of the stakeholders. Included is a stakeholder matrix that can be used to identify stakeholders’ interest in the project and impact, as well as approaches for working with each stakeholder. Use this information to proceed, more fully informed, about probable stakeholder responses during the planning and executing phases of the project.

Here are one student project manager’s thoughts about the stakeholder and matrix worksheet:

I believe this will be an invaluable tool going forward in that it will help me better define all stakeholders early on, further refine my understanding of stakeholder needs, and provide some degree of oversight when planning meetings and communications to ensure nothing is missed. There is nothing worse following project implementation than getting copied on a communication where a missed stakeholder is saying, “No one asked my opinion on this!”

In the past, I have not made any attempt to implement a stakeholder management strategy. In hindsight, I can see a variety of issues that might have been averted, or at least improved upon, had I done so. Going forward, it will be imperative to balance the needs of all stakeholders. In my situation, I believe this should be accomplished by completing a stakeholder registry; analyzing and documenting their stake in the project outcome; recognizing potential conflicts and resolutions; developing an exceptional communications plan; maintaining high visibility throughout the project life cycle; using excellent negotiation skills; and developing mutual trust and respect. These are summed up well as a three-pronged approach: engagement, alignment, and influence.

EFFECTIVE RISK FACILITATION: HANDLING DIFFICULT PEOPLE

The risk management process needs to be conducted throughout project life cycles but especially as a workshop in the planning phase. Many people participate readily while others may not. To assist complete project managers in dealing with these people, we call upon Dr. David Hillson (2016), the Risk Doctor, for guidance:

In addition to being able to flex their facilitation style to meet the varying challenges of the risk workshop and different risk identification techniques, a risk facilitator also needs to handle the people who participate in the risk workshop. Unfortunately, it is common to find at least some participants in every risk workshop who are not fully committed to its success, or who are not willing to contribute freely. There are seven types of workshop blockers, and risk facilitators need to know how to handle them appropriately.

• Aggressive. These people do not want to be in the workshop, think it is a waste of time, and actively oppose what the facilitator is trying to achieve. They are often loud, argumentative and critical, and their behaviour distracts others from contributing.

– Defuse. Give them time to make their point, and do not argue with them, listen patiently, and use conciliatory language. If necessary, speak to them outside the meeting during a break, asking for more tolerance, seeking their active support.

• Complainer. Everything is wrong for a complainer, from the room size or temperature to the meeting time and duration, the list of participants, the type of coffee and biscuits, the agenda and scope of the workshop, and so on.

– Delay. Listen to their complaints and acknowledge anything which is valid. Then agree to address concerns outside the meeting. Deal with immediate matters during a break and take up other issues later.

• Know-it-all. Some people delight in expressing their opinion and demonstrating their expert knowledge of a topic, even when they are not real experts. They have strong opinions and voice them confidently. They are the first to answer every question, often dismissing the views of others as uninformed or naïve.

– Defer. Recognise valid expertise and play back their opinion so they know they have been heard and appreciated, then extend on their input if possible, building on it to regain the initiative.

• Agreeable. While agreeable individuals may appear to be the facilitator’s friend, they often fail to share their true opinion for fear of upsetting someone or being criticised. They smile and nod encouragingly, but shy away from disagreeing with others, and are often reluctant to speak first in any debate.

– Direct. Beware of allowing them to get away with “being nice” and challenge them to express their true opinions. Ask them to contribute first from time to time.

• Negative. These people will disagree on principle with others, seeing it as their role to give the opposing viewpoint (even if they don’t believe it). They undermine the facilitator and other participants by casting doubt on the truth or reliability of their inputs and prevent consensus through constant nay-saying.

– Detach. Maintain a degree of neutrality, not allowing them to get you on their side in criticising others. Accept valid alternative viewpoints but aim for realistic compromise. Depersonalise their opposition, make it about the process or the principle but not about the person.

• Staller. For the staller, there is never enough information to make a firm judgement or to give a clear opinion. They wish to defer everything until later, when more data is available or more progress has been made.

– Delegate. Explore reasons why they are reluctant to offer an opinion on the available data, find out exactly what additional information they require, and give them an action to bring it to the next meeting. Encourage them to give an interim assessment on the current data.

• Silent. Some people just refuse to contribute. They sit quietly but will not speak up to give their opinion, even when challenged or specifically invited to do so.

– Decline. Refuse to accept non-participation or withdrawal. Ask direct open questions, then wait for an answer, using silence as a motivator. Speak to them privately to encourage participation.

Executing Projects

Adaptability and innovation are key aspects embraced by complete project managers. A dialogue with senior project manager Jose Solera, who works in Silicon Valley, helps illustrate many issues that need to be addressed and overcome during the executing phase of project work, especially in software development:

Jose: In late 2006, I joined a high-technology firm to lead the development of the registration and billing capabilities of a Software as a Service (SaaS) product the company wanted to launch by mid-2007, nine months later. As the company was trying to absorb an acquisition made the prior year, they faced a very big challenge—merging to Oracle ERP instances. A year after the acquisition, the merger of the ERP systems had not happened, and IT management had to focus on this challenge.

Randy: What was the imperative that made this a priority?

Jose: It was difficult for the company to close its books. As the acquisition was almost as big as the acquiring company, this created challenges. Plus, the stock market was not happy. So, the imperative came from the CEO down to fix the problem. The inability to merge the ERP systems meant that closing the books required a lot of manual work and impacted the organization’s ability to perform effectively. Hence, all other projects, including mine, were placed on hold for an indefinite period. Oh, the launch date for the SaaS product was still May 2007!

As I looked into how to accelerate the project once we got the go-ahead, I investigated Agile software development practices (e.g., Scrum, XP) as a way to deliver the product much faster than the traditional Waterfall approach. For those of you not familiar, Waterfall dictates that all requirements are captured before design starts. Similarly, design needs to complete before coding begins, and so on. Agile focuses on getting value (product) to the customer as soon as possible in very short iterations, two to four weeks.

I floated the idea of using Agile with the management review committee, VPs from IT, and the customer side. As the company had spent a significant amount of time and resources defining its own Waterfall methodology, I got the answer I should have expected: “You will use our methodology [Waterfall]!” What to do? Time was ticking; we were still on hold.

Randy: What factors were driving the project to be on hold?

Jose: The need to focus IT resources on the merger of the Oracle ERP instances. Almost an “all hands on deck” situation, with all IT resources focused on merging the ERP instances … but launch was still set for May 2007.

I remembered an approach that Intel developed to more effectively and efficiently design their semiconductor products. Described in Timm Esque’s No Surprises Project Management [1999], it focuses on individuals performing the work making the commitments as to when their portion will be done. It encourages communication among team members as well as early warning of any issues. The plan is developed as a group in a meeting called a “map day” because of what the plan looks like. Performance is tracked using simple tools (an Excel spreadsheet). It had been highly effective for Intel, so I figured I could use it in my own software project. What did I have to lose? Traditional project planning and management guaranteed a late delivery and made communicating about the challenge with the client difficult.

Randy: Can you elaborate on how you overcame the management resistance described earlier? What steps you took; did you have a champion or sponsor who supported you; how you proceeded. Did you go ahead in spite of management support or with it?

Jose: I took a risk after letting my direct manager know that I was trying a new approach. I did not ask for permission, although the executives were informed of the planning day, and many were there to launch the project.

With nothing to lose, I went ahead and held the first “map day” in February of 2007, soon after the project was unfrozen. I took a risk, communicating my approach only to my direct manager but not hiding it from others. While senior managers were present to launch the project, they did not remain in the session. If they had, though, I would have argued that this approach would give us faster results.

The output was an excellent high-level plan for the entire project, indicating that while we could not make the May date, we could make an October date. It also made clear the amount of work that needed to be done.

Randy: What was the reaction to this news? How did you address concerns about delays?

Jose: By this point, the client’s team was facing its own delays, and they were willing to accept this change. It was easier than I thought since the main client representative was very reasonable about the situation. It would have been ugly otherwise. The planning was done in one day. As a senior participant said at the time, this approach did in one day what typically takes two months of work.

This approach layers an Agile framework, something we now call commitment-based project management, or CBPM, over a traditional software development methodology. Besides the joint planning, status is monitored weekly at the deliverable level, checking into what is due, what is late, and anything that has not been scheduled. There is flexibility in the commitments, and the messenger is never shot. We encourage issues to be raised as soon as possible. And we were able to still use the Waterfall approach and meet all of its requirements.

Long story short: while we had to adjust the plan to deliver in two phases, one in August and one in November, we hit both schedules perfectly with no issues.

Randy: Did you put additional effort into publicizing this good news? Did these results set a new precedence for future work and change how people operate?

Jose: The teams were recognized for their success and the approach recognized as a viable approach to running projects. As one participant said, there were no crises, and the program ran like a well-oiled machine. The success led to requests for internal training on the approach.

We still had doubters. By this time, senior IT execs were investigating the outsourcing of IT, which eventually was completed in 2008, so the approach did not get the support it could have used.

Randy: Can you highlight your motivation that drove you to become an evangelist?

Jose: I received requests to assist other teams and train them in the approach, which I supported. Since then, I have applied this approach in other areas. With a defense client, we applied it to the development of the third-stage control system (hardware and software) of a defense missile. With a major university, we applied it in the development of a radiation dosimeter to be used in case of a major radioactive disaster. In both cases, the approach has complemented the product development methodology, ensuring better performance by the teams.

With all these successes and the experience teaching at my company on the approach, I started delivering seminars on how to plan and execute using CBPM. I have automated the tracking process using Excel and have made the tool available to those attending my workshops as well as others interested in it. Through these workshops and workshops by Timm Esque and others, many project managers have been able to successfully apply this approach.

INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

Innovation is often expected during a project’s execution phase. Based upon his long and varied career in both commercial and government organizations, Thomas J. Buckholtz shared with us the following lessons on innovation management.

I would like to suggest several operating principles for innovation management. These principles generalize lessons learned from innovative endeavors in which I participated. I hope people will evolve these principles into yet more useful statements and will use at least similar principles to foster beneficial innovation in their projects, programs, and portfolios.

I illustrate each principle based on my having led a companywide innovation program that included Pacific Gas and Electric Company’s (PG&E) first use of personal computing. Less than three and a half years after I joined the company as the leader of a small group in the computer department, I announced in a presentation to corporate officers, “We have 5,000 computers. I’ve spent $20 million of the company’s money. And you here in this room have signed off on $100 million in recurring annual benefits.” The annual cost savings equaled about 1.5 percent of corporate annual revenue.

• Assume that almost anyone can have an idea that can lead to an appropriate innovation. This program embraced proposed innovations—mostly quality and productivity improvements—from people throughout the company. Projects were started by people holding job titles of clerk through director. Some projects involved localized work for which there had been no computer support. Other projects involved work—such as meter reading—for which there already was mainframe-based support but not automation at the point of data collection.

• Observe—and possibly change—innovation culture. Early on, I noticed that conversations often centered on technology. I tried to change the dialogue to focus first on results for the company, customers, and employees; second on human infrastructure such as teamwork, innovation, sharing, and learning; and third on technology. After my group began publishing a newsletter, I recommended featuring work-improvement successes, not technology topics, as the lead stories.

• Consider emphasizing principles, along with or instead of goals. My group developed and announced the following seven principles:

—Meet individual and departmental needs, both those needs that are common throughout the company and those that are specialized.

—Deploy easy-to-use systems.

—Encourage self-sufficiency for organizations and people using technology.

—Foster integration of processes and technology.

—Foster flexibility for accomplishing and sharing work and for taking advantage of changing technology.

—Integrate office technology−based information into the company’s overall information resources.

—Promote proper sequencing and timing of progress.

It was not feasible to establish targets for outcomes. We used the principles to foster compatibility between individual projects and broader corporate needs and to decide when to become interested in new types of software and hardware.

• Leverage the contacts and skills that championing innovation brings. Based on the company’s chief economist’s desire to meet industry leaders in Silicon Valley (part of PG&E’s service territory), I arranged a meeting with the chairman of Intel. I found an opportunity for the company to learn about deregulation of the United States transportation industry. The meeting that ensued included two of the three top leaders of the company. I arranged a Rotary Club speech for a CEO of the company.

News media coverage of the program featured first our pioneering of the corporate software license and later the successes of various innovation projects. After I had provided several media interviews, the corporate public relations function allowed me to schedule and hold interviews without its involvement.

I also gained autonomy from the law department and helped negotiate contracts without the involvement of a company lawyer.

• Encourage exploration and mitigation of the risk of derailment. The program-leading group served the entire company, including the traditional administrative and engineering clientele of other parts of the computer department. There was a risk of undue rivalry within the computer department. My group encouraged other computer-department groups to embrace personal computing as part of the repertoire of technologies and services these groups offered to their clients.

More generally, there is no guarantee that an innovation program, an innovative concept, or a specific innovation project will not get derailed. Corporate leadership can derail an innovation culture by defunding research-and-development efforts and groups. Or, for example, starting in 1980, the United States federal government established the discipline of information resources management (IRM)—the combination of knowledge services (sometimes called knowledge management or records management), computing, and telecommunications. As a commissioner in the United States General Services Administration (1989−1993), I led an organization that included a group that served as co-CIO for the U.S. federal government’s executive branch. The federal community made progress based on the IRM vision. Yet, it would appear that during the mid-1990s, emphasis shifted toward program management and technology management, and the focus on information as resource lost prominence.

I hope that people gain from the above perspective, try to use some of it, provide feedback and otherwise share knowledge of what they do, and thereby help society take advantage of what people learn and help create.

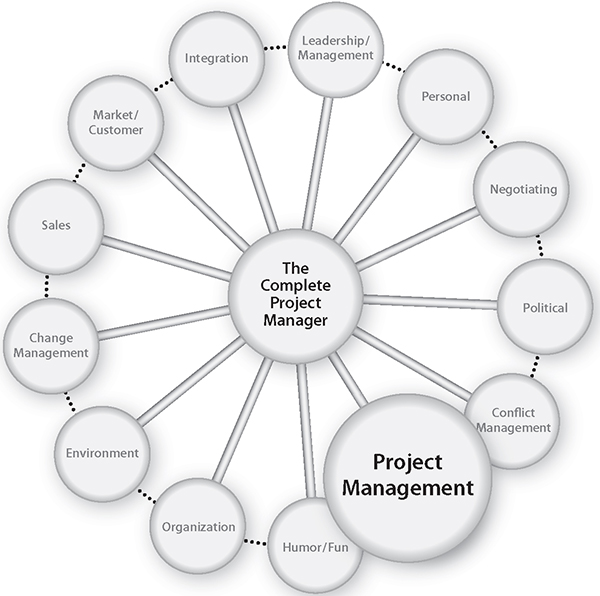

Control or Results?

In most organizations, producing unique project results provides the means to achieve success. Monitoring and controlling projects are core processes, conducted particularly during the execution phase of the project life cycle, in which progress is tracked, reviewed, and regulated to meet performance objectives in the project management plan, including the implementation of corrective or preventive actions to bring the project into compliance with the plan when variances occur.

When managers do not get desired results, careful observation reveals that they put greater emphasis on increased controls, such as tighter metrics and detailed status reports. In project work, where we may not always know what results are possible, the paradox is that managers often need to give up control to get successful projects and achieve business objectives. People say they want results, but they act as if they want control; they resort to a command mode. The command-and-control model is deeply embedded, but it does not serve us well in modern organizations.

Project work finds us floating in an ocean of data and disconnected facts that overwhelm us with choices. At its most basic, the choice on projects is between control and results. The goal of every project is to achieve results. A common view is that managers need to be “in control” to achieve those results. However, onerous controls inhibit achieving the very results intended because they demotivate and limit how people approach creative work. It is possible to pursue both control and results—up to the rare point where the two actually conflict. A key question for the complete project manager to address is, which value will you choose when control and results conflict at the point of paradox? If control is more important, the cost is lesser results. If results are more important, the cost is giving up some control. Getting more of one requires sacrificing a portion of the other.

Controls often suggest that managers do not trust workers, whether this is the intended effect or not. When trust is not present, extraordinary results are missing as well. Let us first discuss the nature of paradoxes. Then let us explore how to work through the paradox and achieve greater project results.

I (Englund) have had the privilege of coauthoring several books, articles, and workshops with Dr. Robert J. Graham. As a cultural anthropologist, Dr. Bob was trained to observe unusual behavior in tribes. Through his mentoring and guidance, I came to appreciate the value of observation. I also came to appreciate the power of questions and the questioning process. One question we investigated is, “Do you want control or results?” Most people, of course, say that they want results. But when we observe what they actually do, it becomes clear that control is paramount.

Asking the question is perhaps more powerful than any answer, for the question prompts people to reflect upon their experiences. I once spent a couple hours in discussion with a high-level scientist at Motorola who was intrigued by the question. The preference is to have both control and results, but that is not always possible. The quest for control is inherently flawed, since it is not fully possible to be “in control.” Herein lays the paradox: you need to give up control to get results.

So, we need to:

• Identify the nature of paradoxes and how they impact the achievement of project results.

• Discuss how to change thinking processes to focus on what is most important for business success.

• Apply a set of ideas, leading practices, and examples to project-based work so that increased productivity can be realized immediately.

THE PARADOX

There are several definitions of paradox:

1. A statement that is seemingly contradictory or opposed to common sense and yet is actually true.

2. An apparently true statement that appears to lead to a contradiction or to circumstances that defy intuition.

3. A person or thing showing contradictory properties.

4. A statement that leads to an instant, infinite contradiction.

Our paradox can be stated as follows: In project-based work, managers may need to give up control to achieve results.

A paradox by definition cannot be resolved. In order to resolve the dilemma between control and results, we have to redefine what we are doing and how we view these values to avoid creating the paradox in the first place.

EXAMPLES FROM PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Do people rave about Hero A, the crisis fighter, or Hero B, the project manager and team who prevent the crisis in the first place? Who were the heroes of Y2K—those who worked hard to make the turn of the millennium a nonevent for computer systems, or those who responded (or were prepared to respond) to system crashes? Most organizations want heroes and planners, but which do they choose, and reward, when it comes to operating the organization? Beware of rewarding the firefighter “hero” who resolved the crisis but who may have been responsible for creating the “fire” in the first place (see Figure 6-2).

Figure 6-2: The Firefighter “Hero”

Organizations may find that they need to overcome heroic symbols. Early on, AT&T became famous for its ability to pull off miracles in times of natural disasters. The “rescuers” were often treated as heroes, symbolized by the Golden Boy (shown in Figure 6-3)—a 24-foot-high statue depicting Mercury’s speed, the era’s sense of mystery about all things electric, and the modern messenger, the telephone. AT&T’s mission was to wire the world. This mentality carried over and became incompatible with the project management approach that became necessary in the modern organization. Admiration for heroic rescuers had to be replaced with admiration for doing a competent job. And paradigm shifts—from wired to wireless, for instance—also drive the need for new behaviors and attitudes.

Another question to ponder: does a credit-processing organization such as Visa, which adopts a zero-defects approach to transaction processing for credit cards, carry that approach over to managing projects, creating an environment that demands perfection before completing projects? Be aware that historic foundations may hinder implementation of new processes or innovation initiatives. Honor these traditions while building a case and support for new ways to monitor and control projects.

CASE STUDY

An internal service group had been operating as a project office in a self-funding mode: internal clients “purchased” services and products via transactions or location code transfers. Budgets were based on head count, and offerings continued as long as clients saw value and voluntarily provided enough revenue to recover costs. In this mode, the group sponsored periodic events that became quite popular, offering attendees exposure to external experts and best practices that colleagues were implementing.

Shortly before one big project was about to complete, an intense cost-cutting requirement was imposed by senior management. The director above the internal service group unilaterally imposed cost controls. He did this to set the standard for the rest of the organization, believing the project was too visible and that people would not control costs on their own. This mandated action was in sharp contrast to the volunteer-based, self-funding model. The program manager was not asked how to conduct the project at lower cost but was told to either cancel it or make drastic reductions dictated by the director.

Figure 6-3: The Golden Boy

In this case, the director placed higher value on a show of action for reducing costs than on completing a project that was perceived by many to be extremely valuable. People resented his message, which took away their choice about whether or not to participate. The program manager passionately argued for continuing the project because a carefully constructed set of offerings had been designed to meet client needs. He demonstrated the costs of cancellation with no value received, as opposed to continuing and receiving at least some marginal value, and thus received approval to continue—but was told to do so with one-fourth as many participants.

The program manager’s focus all along was on offering a valuable outcome versus staying within budget or tracking the breakeven point. He believed that if value is present, the funding would be there. This belief was tested by the director’s actions, which seemed driven by other concerns. The program manager’s passion and persistence, as well as his courage to push back against oppressive pressures, saved the project (and also served as an “educational opportunity” for the director). Except for the pain they created, the director’s short-term cost-cutting actions were given little or no credit and were soon forgotten. Long after its completion, however, people still remember the good things that this project delivered.

Figure 6-4: Control vs. Results

Telling this story usually elicits a response such as: “Thanks, Randy! Once again, exposing the ridiculousness of arbitrarily setting some measurement or target makes an excellent point!”

People on projects often face similar dilemmas, in which two deeply held values are in opposition: do I want to create value or control costs? There are no easy answers, because the conflict is a matter of right versus right. Individuals need to be clear on their values in order to navigate this difficult territory. Figure 6-4 depicts the balancing act and its consequences.

The ideal situation is to have optimum controls that achieve desired results. Desired results are usually identified by purpose, vision, and mission statements; by elements in the project charter; and by discussions with key stakeholders. The optimum controls to achieve those results, however, are often less clear. They may be derived from experience, discussions among project teams and sponsors, or by accident. When controls are not present or are minimal, the results appear chaotic, meaning the deterministic aspects of project performance are lacking. Excessive controls, which are present more often than not, lead to the undesired results that we want to address.

DRAW UPON COURAGE

We live in worlds of conflicting values or priorities. It takes courage to make tough calls. Resolve conflicting values and hidden dilemmas by engaging in dialogue with key stakeholders. Trust your judgment about what is most important. Take a stand on which value you choose at the point of paradox, that point where it becomes impossible to achieve both values. What is most important: being a hero or a planner? Control or results? Outputs or outcomes? You can then pursue both values up to the rare point where the two actually conflict; at that point you need to choose, and make clear to others, what is most important.

Whatever action is taken requires moral courage, especially if the action is more difficult, less popular, different from tradition, something new or experimental, or goes against the flow. Realize that these latter options typically lead to breakthroughs—and also come with commensurate risk. Rely on your passion and a sense of belief in doing the right thing to summon energy and courage to persevere. At the same time, be mindful of feedback and new information that may lead to the need to take a different approach.

FOCUS ON VALUE

Many groups appear risk averse. In our experience with professional organizations that sponsor major events, an inordinate amount of discussion goes into pessimistic forecasting, angst around breakeven points, and tasks. Sometimes we suffered through these discussions quietly. We then spoke up and reminded the group of the First Law of Money (Phillips and Rasberry 1974): money will come when you are doing the right thing. We refocused the discussion on why we were doing the event, reinforced that its purpose was to contribute to the professional community (not just prevent the organization from losing money), and engaged others in clarifying the value the event offered, both to promoters and participants. If the value was indeed there, we could charge appropriately, and people would come.

We need to be enthusiastic about the projects we do. It is that enthusiasm, and its source, that will be contagious, drawing others in to participate.

TELL A STORY

People have always learned lessons through storytelling. Telling a story makes the impersonal personal. I (Bucero) once worked in an organization where I was required to provide daily sales reports to a general manager. The time required to do these reports detracted from my ability to get out and sell. I believed in the services I had to offer but was diverted and bothered by the emphasis on the numbers. I was literally in pain, but I realized relief when I decided to leave the company and create my own business. My professional values were in conflict with the security of this position and the excessive reporting requirements.

Sharing examples like this helps others understand the values that are in opposition, shows how others have ultimately resolved their own conflicts, and provides motivation to do the right thing.

WORKING THROUGH THE PARADOX

Our experiences make it clear that at the point where it becomes impossible to achieve seemingly contradictory values, we may need to give up some control to get results. Control, after all, is an illusion. Nature is firmly rooted in chaos. We try to convince ourselves and our bosses that we project managers are in control of our projects. We may come close to this illusion, and we usually are far more knowledgeable about the project or program than anyone else. Try as we may, however, the fact remains that far more forces are at work in our universe than we can ever understand or control. But this does not relieve us of the obligation to achieve results. What should we do to monitor and control projects?

Focus on results and constant course corrections to stay on track. Capture the minimal data required to keep informed. Seek information that supports action-oriented decision making. Just because we can capture every conceivable piece of information does not mean we should, nor can most organizations afford to do so. Excessive reports and metrics may support a feeling of comfort, but that feeling is deceptive. Continuous dialogue with stakeholders and reinforcing intended results are more effective means to relieve anxieties.

Use brevity, clarity, and a story to reveal your personal feelings about an issue. Tell personal stories. Sharing feelings stirs up feelings in others—and wins followers. Believe that results are possible, but they may not follow a clearly defined path. Draw upon courage, and avoid the temptation to impose excessive controls, understanding how detrimental that may be to achieving desired behaviors. Be flexible and enjoy the ride!

Closing a Project

The following story is about failure to get complete closure after a project and how that affected the motivation of its participants.

A professional association sponsored a major event that involved the participation of all chapters within the region. The planning of the event followed most steps required in the project management process: a vision was created and agreed upon; speakers who were known to have a valid and compelling message that fit with the event’s established theme were invited; sponsors were signed up; the event was well publicized, with promotional materials citing key messages that would be covered; and weekly status meetings with all project participants were held. Key documents were posted and available to all at a SharePoint website. The project manager drafted a “day in the life of” scenario that allowed planners to step through all details of the project to ensure no tasks were incomplete. Enthusiasm was high, response was equally high, the event happened as planned with attendance at maximum capacity for the site, and financial returns for the association were bountiful.

I (Englund) was the content and program director for the event. The problem, in my mind, came after the event concluded. As volunteers who put much time into this project, we wanted assurance that the reasons for our project’s success were clear, that we’d met all our goals, and that our work was recognized. Surveys of attendee reactions were conducted, but the results were not shared among the team. The final numbers from accounting were known to only a few. A set of resourceful and productive volunteers was assembled but then disbursed. Lessons learned, or best practices applied, were not captured. Subsequent events did not replicate key factors that made this event successful, and those later events did not generate the same level of participation as this event.

I was able to influence the upfront design of this project, such as running a single track so that all participants heard all messages and inviting known speakers with known messages instead of putting out a call for papers. I was not able to get the project manager and sponsoring organization to schedule a follow-on project review. We all got busy after the event, and a review date was missing from our original plan, so it never happened. The result was that some individuals felt this was an incomplete experience, that all the hard work went for naught.

People want closure, especially after a successful project. We learned from each other and had fun together, but I sensed that this event was not regarded with the same level of high regard that I felt about it, simply because there was no forum for sharing those feelings. It seems like no news is bad news. A suggestion to share financial returns with key contributors was summarily dismissed, even though it was in the budget; follow-on summary reports and A/V materials were not made available to participants as originally planned. I believe we “stretched the rubber band” about how to conduct an event like this, but the organization snapped back to how it always operates. We lost the opportunity to generate a longer-term impact in our community and build upon messages generated by the event. As a consequence, I am now less willing to participate in other projects for this organization.

As a project team member, I had to take accountability that we did not achieve the desired closure. I also realize how dependent we were upon the project manager to guide us through this stage. We needed someone to urge us to complete unfinished tasks. Since that did not happen, we were left with unexplored feelings.

This experience underscores for me how influential a project leader is with regard to all aspects of projects, from beginning to end. If the ending—meaning the cathartic process of debriefing what went well, what we should do again, and what we should revise—is not complete, then people are less motivated to apply their best efforts to future work. Since people’s attention during the closing stages naturally shifts to the next activity, it is imperative for the project manager to exert significant effort into ensuring that closure happens. Failure to do so is a lost opportunity to influence perceptions—about doing work together in the future, about how important projects are to this organization, about making it a priority to learn together and apply those learnings to future projects, and about rewarding people for their best work.

PROJECT REVIEWS

During the entire project life cycle, the project manager usually collects a lot of knowledge. Sometimes that knowledge is not reused—people reinvent the wheel again and again in future projects. Many managers and project managers, and ultimately the organizations that depend upon them, lose the opportunity to learn from their projects because they do not take the time to analyze past results during the project life cycle. So, the question that comes to mind is, how can we manage project knowledge?

After many years in the project business, I (Bucero) have always found that project managers from different countries in Europe live the same experience: there is a lack of time to stop, analyze, and learn from past experiences. When I was working for a multinational company that sold customer IT projects, I had the responsibility to define and implement a knowledge management process for my consulting organization. Junior and senior project managers were supported by our project office. All of them said, “We are reinventing the wheel for every new project, and we don’t have the opportunity to spend time talking among the team about our projects.” It was a crazy situation, but that was reality.

Learning from past experiences is not a priority in many organizations. In the solution-selling business, upper managers want to sell more and more, but learning from projects they sponsor does not seem to matter to them.

As a solution-selling organization, we had to achieve profitable results from our customer projects. At that time, project results were not very good, but the strategic direction was to improve and achieve the next maturity level for the organization. Then I proposed implementing improved processes using a project office and received a green light from upper managers to begin.

Initially, we started by identifying projects in our portfolio and also by identifying the skills and experiences of project managers in the organization. Then we, as a project office, delivered a presentation to project managers and managers about how to collect useful information during the project life cycle, taking into account the time and cost restrictions in our organization. The result was to implement “project snapshots,” half-day sessions whose purpose was to capture lessons learned during a project, identify knowledge for reuse, and identify opportunities for skill or methodology improvement for all project stakeholders.

What were the objectives of these sessions?

• Reflecting upon successes and lessons learned in project selling and implementation phases

• Focusing on key themes such as project and scope management, communications, issue management, problems, and successes

• Leveraging successes and learning to more effectively deliver subsequent phases or projects for clients

• Identifying tools and best practices that could be shared more broadly.

What was the value of the project snapshot sessions? They generated value for the professionals, for the project team, for the project manager, and for the rest of the organization. For professionals, they leveraged team members’ work and experience through the sharing of lessons learned, prevented redundant activities by making sure that all team members understood what each person was working on, and resolved issues earlier in the project by getting them surfaced and resolved.

For the project team, the sessions leveraged learning and successes for ongoing project work, helped align everyone on a given project for a more consistent implementation, and gave the project team and selling team a better understanding of client perspectives (when clients were involved in the sessions).

Other project teams learned how to reuse existing tools, identified project teams that had completed similar projects, and were able to use their learning to enhance project outcomes and avoid costly mistakes.

Project managers came to understand successes in delivering particular methodologies and solutions and recognized opportunities for selling and delivering solutions.

For the organization, the sessions allowed the elimination of non-valueadding work, and more attention was placed on improving customer satisfaction and increasing sales.

Business Analysis Skills for the Project Manager

Business analysis is emerging as an increasingly important function in every organization. It is really all about choosing and defining a desired future—analyzing business needs. Most organizations do some form of business analysis whether they use the term or not. For many organizations, it is an extremely structured, managed process, while others thrive on change and only do business analysis when and as needed. The perception that business analysis is only needed to develop IT solutions is inaccurate. Actually, it is a critical component of any change initiative within an organization whether software is involved or not.

Some level of business analysis skill is essential for any project manager in the business world today. I (Bucero) needed to play the role of business analyst in the first phase of some projects because previously I was an analyst, and I had some resource constraints. That situation helped me to understand much better the customer business needs. Many of the techniques used in the field evolved from earlier lessons learned in systems analysis and have proven themselves to be useful in every walk of professional life.

The following skills are specific to the business analyst role, but even as a new business analyst or someone looking to enter the profession, you’ll see it’s possible to relate transferable experience doing similar work under a different title—for example, as a project manager.

• Documentation and specification skills. The business analyst or the project manager working in that role includes the ability to create clear and concise documentation (the latter becoming increasingly necessary in a lean or agile world). You may not have experience in a variety of business analyst specifications (that comes with time and a variety of project experiences), but it’s quite possible that your strong general documentation and writing skills will get you started.

• Analysis skills. Business analysts use a variety of techniques to analyze the problem and the solution. You might find that you naturally see gaps that others gloss over and identify the downstream impact of a change or new solution. As you mature in your business analysis skills, you’ll use a variety of techniques to conduct analysis and deconstruct the problem or solution. There are three key levels of analysis that are important for fully understanding a problem and solution domain, when software is being implemented as part of the solution. These are:

• The business level, or how the business work flows operationally, often completed by analyzing the business process

• The software level, or how the software system supports the business workflows, often completed through functional requirements models like use cases or user stories

• The information level, or how data and information are stored and maintained by an organization, completed using a variety of data modeling techniques

• Visual modeling. As part of learning the analysis techniques, learn to create visual models that support your analysis, such as work-flow diagrams or wireframe prototypes. For any given analyst role, there could be specific models that need to be created. As a general skill set, it’s important to be able to capture information visually—whether in a formal model or a napkin drawing.

• Facilitation and elicitation skills. In order to discover the information to analyze, business analysts facilitate specific kinds of meetings. The most common kinds of elicitation sessions a business analyst facilitates are interviews and observations. In some more advanced roles, the meetings are called “Joint Application Development (JAD) sessions” or “requirements workshops.”

• Business analysis tools. As a new business analyst, the ability to use basic office tools such as Word, Excel, and PowerPoint should be sufficient to get into the profession. Other technical skills include the ability to use modeling tools, such as Visio or Enterprise Architect, requirements management tools, such as DOORS or Caliber, or project and defect management tools.

• Relationship-building skills. First and foremost on the list of soft skills is the ability to forge strong relationships, often called stakeholder relationships. A stakeholder is simply anyone who has something to contribute to your project, and often you’ll work with many stakeholders from both business and technical teams. This skill involves building trust and often means stepping into a leadership role on a project team to bridge gaps.

• Self-managing. While business analysts are not project managers, the most successful business analysts manage the business analysis effort. This means that the business analyst is proactive and dependency-aware. It also means they manage themselves to meet commitments and deadlines, a skill set which can involve influence, delegation, and issue management.

• A thick skin. To succeed as a business analyst requires the ability to separate feedback on documents and ideas from feedback on the person.

• A paradoxical relationship with ambiguity. Business analysts despise ambiguity. Ambiguities in requirements specifications lead to unexpected defects. Ambiguities in conversation lead to unnecessary conflict. At every stage of a project, you’ll find a business analyst clarifying and working out ambiguities. Yet, at the beginning of a project, before the problem is fully understood and the solution is decided upon, a business analyst needs the ability to embrace ambiguity and work effectively through vague situations. Managing ambiguity means embracing new information and learning as it surfaces, even if it surfaces later than we’d like.

HOW DO COMPLETE PMS NEED TO WORK BUSINESS ANALYSIS INTO THEIR PROJECTS?

The first step we encourage you to take as a project manager is asking: what is the reason for this project and why has it been assigned to me? That means that the project manager would read the business case or perhaps participate in its generation, depending on the type of project, acting as a business analyst.

Afterward, the project manager needs to participate in getting business requirements agreed upon with the customer, sponsor, and other stakeholders, so he/she will need to supervise or even participate in requirements elicitation, gathering, and validating, using the techniques explained above.

The major outcome the complete project manager needs to obtain from these activities is contributing to and generating greater business value.

Creating Project Excellence

Pursuing excellence in project management is, obviously, a worthy goal. Thompson (2008) says that based on his personal experience and the literature, he has uncovered that certain traits need to be in place to make the difference between success that lasts and groups that lose their edge:

1. Meaning is more important than perfection.

— Focus on a few things that matter.

— Set priorities and avoid distractions.

2. The environment always wins.

— Remove obstacles from the workplace.

— Recognize people doing things right and doing what matters.

3. Lovers finish first.

— It’s essential to follow your passions.

— Be able to leap back into action when things get difficult. (Thompson 2008)

We also believe a sense of purpose contributes to creating excellence. Nikos Mourkogiannis writes, “The pursuer of excellence seeks action that constitutes innate fulfillment for its own sake (and thus ‘beautiful’ or ‘elegant’)…. How can leaders use Purpose to create advantage? Leaders do not simply invent a Purpose; they discover it, while at the same time developing a strategy and ensuring that Purpose and strategy support each other. This requires that they listen to themselves and their colleagues, and are sensitive to their moral ideas, as well as being aware of the commercial opportunities offered by the firm’s strengths” (2008).

By applying the above concepts and by creating excellence in project management, complete project managers, together with project sponsors, set the stage to create organizational excellence through project management. This means:

• Obtaining significant advancements in the maturity of people, processes, and the environment of a project-based organization

• Optimizing and achieving greater results from project-based work

• Realizing a competitive advantage by executing strategy through projects

Bruce Edwards, CEO of Exel Corporation, says that excellence in project management at the organizational level is characterized by:

1. A project-centric organization

2. A project-based culture

3. Strong organizational and leadership support for project management

4. A matrix team structure

5. A focus on project management skill development and education

6. Emphasis on project management skill track

7. A globally consistent project management training curriculum

8. Globally consistent project management processes and tools

9. Template-based tools versus procedures

10. Multilingual tools and training

11. Acknowledgment and support of advance certification in project management (Project Management Professional [PMP], Certified Associate in Project Management [CAPM])

12. The presence of internal PMP and CAPM support programs for associates

13. Strong risk management

14. Project management knowledge sharing

15. Organizational visibility of the portfolio of projects and status through the use of enterprise software such as PlanView. (Kerzner 2010, 108–18)

Creating excellence involves forming a picture of an ideal environment—in terms of people, processes, and the environment—for implementing projects and requires an honest assessment of the current reality. By getting expert feedback and sharing examples, actions, and improved practices that will help bridge the gap between reality and ideal, you can prepare yourself to transform your approach to project management, no matter where you work.

ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY

We believe project success on any major scale requires you to accept responsibility. The one quality that all successful people have is the ability to take on responsibility. We strongly believe that a project leader can give up almost anything except responsibility. Complete project managers never embrace a victim mentality. They recognize that who and where they are remain their responsibility. They never complain. In addition, project leaders lead by example and transmit to their people that a sense of responsibility is fundamental for team and project success.

The intensification of competition and the difficulties reaching a wide range of consumer segments causes reduced profit margins for many industries. Projects that transform companies or industries need project managers capable of managing a complex set of requirements. These requirements often involve new technologies, changes in operating procedures, and different ways of working. Complete project managers embrace curiosity and accept responsibility for implementing changes that may emerge.

The Competent Project Manager

Competence is the ability to perform a specific task, action, or function successfully. Project management competence goes beyond simply talking the talk. It is a leader’s ability to say it, plan it, and do it in such a way that others know that he knows what he is doing and know that they want to follow him. Competent project managers also close the loop—they learn from each project. They are professionals who are always ready to learn and are always going one step beyond. They are people who overcome a fear of making mistakes, who are able to recognize better ways to get a job done, and who can learn from successes and failures and from others. Competence is a key to credibility, and credibility is the key to influencing others. Most team members will follow competent project managers.

Table 6-1 depicts three levels of competencies:

Table 6-1. Competency Levels

Individual

• Knowledge-based

• Socially rooted

• Business judgment

Team

• Clearly defined goals and deliverables

• Proper mix of skills

• Adequate processes and tools

Organizational

• Procedures and information to perform work

• Trained resources

• Vision, openness, and support for project management

Competence is rooted in a variety of factors:

• Motivation

• Energy

• Intelligence

• Skill level

• Knowledge

Each of us tends to be competent in one or a few of these areas. However, highly competent people are skilled in all of them. Incomplete project managers may need to focus on industries or areas where they possess knowledge or skills. Complete project managers who are highly competent in all of them may usually be successful no matter where they work.

We advise to build on people’s strengths. Design work to fit the worker, not the other way around. Best results occur in organizations where all three levels of competencies are properly aligned—across individuals, teams, and the organization.

In short, competent project managers are:

• Those who can see what needs to happen

• Those who can make it happen

• Those who can make things happen when it really counts

People admire project managers who display high competence relative not only to the project management process but also in related and necessary disciplines. Do research to find three things you can do to improve your professional skills. Then dedicate the time and money to follow through on them.

Remember that you are as good as your personal standards. Review your standards, keeping in mind that people have no limit to their ability to progress, learn, and move forward—adding more “molecules” to your skill set. At the end of this week, take a moment to make a plan to improve your competency level. Strive to improve competency of those people around you as well.

Agile

An ongoing trend is toward adopting Agile methodology, perhaps in place of traditional Waterfall or in a mix with other techniques. Agile methodology is an approach typically used in software development and in other areas when modular construction can be applied. It helps teams respond to the unpredictability of building software through incremental, iterative work cadences, known as sprints. This approach may greatly reduce both development costs and time to market. In Agile paradigms, every aspect of development and design requirements are continually revisited throughout life cycles, focusing on a module at a time.

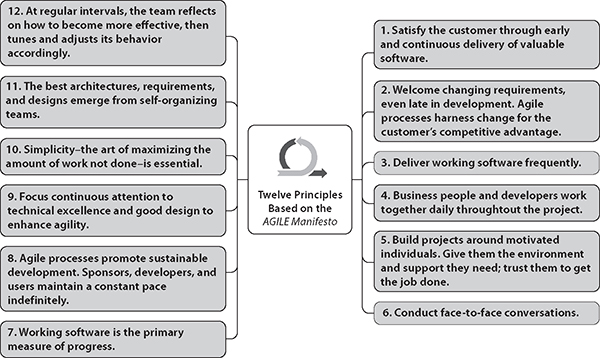

Figure 6-5 highlights key principles of Agile methodology, drawn from the Agile Manifesto, serving as guiding practices that support teams in implementing and executing with agility (see more at www.agilealliance.org).

Agile devotees appear like evangelists, stating this as the best approach. Complete project managers are wise to investigate and use this approach when appropriate or use it as another tool when suitable, perhaps in a hybrid approach with other techniques. Training is recommended when tasked, for example, to become a ScrumMaster who administers the sprints. Discipline is still required when using this methodology. Leaders need to create environments that support self-managed teams.

On a project that had a very hard, aggressive deadline and required several legal and financial reviews, with lots of contingencies, Michael Thompson at IBM decided straight Agile did not make sense:

“I used the bare minimum waterfall to lay out milestones of what would have to happen when and how we would achieve each milestone and then incorporated agile into that,” he says. That hybrid approach allowed the team to pivot more quickly when it encountered a setback, without fear of blowing its hard-and-fast reviews. “We were flexible enough to roll with the punches and firm enough to deliver,” he says. (Thompson 2017)

Figure 6-5: Principles of Agile

Summary

Producing unique project results is the aim of the project management process, which spans five stages from initiating to closing each and every project. A foundation based on PMI’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge is a starting point. Throughout the journey, seek best practices in each phase of the project life cycle and apply them. We share in this chapter a few practices that we have found helpful. Keep focused on people and the results they can achieve. Invoke clarity of purpose through problem and vision statements.

Create excellence in project management, both by developing skills and implementing processes, and move on to create organizational excellence through project management, by tapping contributions from business analysis and utilizing a high-performance project-based organization that optimizes outcomes. Develop a set of competencies that reflects a high standard. Take responsibility for your actions. Be careful not to become too rigid in your approach; stay flexible when working with others; use methodologies appropriately.