11

Sales Skills

If you don’t believe in your project, you will not be able to sell it.

—ALFONSO BUCERO

Some years ago, when I (Bucero) worked for a multinational company, my manager said to me, “You don’t have sales skills. You will not ever be able to sell any project at all. You are too good—in a world of wolves, you cannot be a lamb.” As the years passed, I observed my business results, and I noticed that many of my project sales were indirect, meaning that I am selling when I am delivering a project. I also am selling when consulting within an organization. My only lament is, how much more effective could I have been if I had consciously embraced the sales process?

When dealing with external clients or customers, we are always on display. Customers look for professional behavior as one measure of credibility. They observe project managers almost all the time, looking for professional conduct, reactions and behaviors, how they make decisions, and how they deal with people. They also look to these people as trusted advisors—people whose opinions they seek out when making decisions. Sharing opinions is part of the selling process.

To be on a path or journey to become more complete, as persons, as project managers, and as organizations, we need to sell the idea or concepts to colleagues. Wait, did we just say sales? “We are not salespersons. We don’t have sales skills. We do not even like selling.” Or perhaps we need to think differently?

Within organizations, creating awareness of project management’s true potential and value at a strategic level increasingly involves selling project management as a core, necessary discipline. Project management professionals do not exist in a vacuum; they work in organizations, and they need to convince their managers of the value of project management. This means selling project management to make others, especially higher-level executives, aware of the benefits not only for a particular project but within the entire business context.

Depending on their maturity level, organizations react differently to project management initiatives. Project management has greatly evolved over the last decades. Starting a PMI chapter in your part of the world helps create project management awareness, but in and of itself, that is not enough to advance the profession. We have found that one of the keys to gaining project management acceptance is to spend time explaining the meaning of project management to executives. However, these people are not always available and ready to listen to you.

As people develop proficiency in all skills covered previously in this book, it becomes increasingly necessary to sell the ideas, concepts, project plans, and so forth to others. In this chapter, we address the selling skills required of complete project managers. Actually, all professionals, and most everybody for that matter, can advance their causes and their careers by recognizing the need for developing and integrating sales skills. We provide further detail about the more formal sales proposal process when responding to requests for proposals.

What Are We Selling?

So, what are the sales skills the complete project manager needs to develop? We believe that the first skill is to learn to sell your value and experience. Projects are led by people. Customers may buy, or not buy, depending on the people who are leading the project. Most buying decisions are emotional. Selling yourself is related to self-image, credibility, integrity and authenticity, speaking the truth, and knowing customers and their organization very well. These things take time and effort, so plan to put in that effort.

I (Bucero) was part of an international team at Hewlett-Packard. That group implemented project management offices worldwide. The program manager made an extraordinary effort to explain to each management team how the PMO added value to project team members, to the organization, and to customers, and provided visible signs of management commitment, competent team support, and improved project and organizational performance.

The key to getting upper management support at this point (selling the project) was showing how the PMO solved current problems and provided immense business impact. A complete business case was presented to executives (written in “management-speak”).

The PMO stakeholders were managers of the businesses and solutions that influenced both end users and upper managers. Through a stakeholder analysis, I could determine how different individuals influenced decisions throughout the project. This kind of analysis helped me understand the levels of concern and authority of management teams—and how those behaviors or patterns influence the delivery of results by project managers.

A short-term business orientation is not compatible with a project-oriented business approach. Projects need to be planned and implemented; project managers need to be trained, mentored, and coached; and projects need sponsors. At HP, for example, I sold the need to upper managers to be trained in sponsorship. I was able to demonstrate that, although the project sponsors were not active members of the team, they were a resource that served as motivators and barrier-busters. Most upper managers believe project management is something tactical and relevant to project managers only. I spent significant time delivering short talks and workshops, speaking the language that upper management understands—talking about profit, strategy, goals, and how to get better results. I did many face-to-face meetings with different management levels, but I was not successful at the beginning. Persistence and discipline were the keys to project success.

Be in the Game

Effective sales skills require its participants to be “in the game.” For example, car salespersons have a script they follow when interacting with customers and the sales manager. Buyers who are not aware of this “game” may not achieve optimum outcomes.

Here is what we mean by games. Games have rules. Each player in the game has a role, or tasks, and shared goals. To be in the game means I learn, understand, and agree to abide by the rules. I can be penalized for violating the rules. Games have scores or metrics. I win, lose, or tie against others in the game. I choose to play the game … or not.

When viewing project work or sales interactions (or any other activity for that matter) as a game, that means I know the rules and understand standard practices. An organization may have a certain way to conduct work on projects, request resources, or present proposals. I can get into trouble when doing it differently. People may resist or refuse to operate in a different way. The project may not achieve desired outputs and outcomes. I (Englund) was told one time that before I suggest doing something a different way, I need to fully understand the way it was done now and why. This “sensitivity training” was a valuable lesson for me.

So now I have options. Once I understand the game and its rules, I can play the game as usual or even better than ever before. Or I can decide to change or make up new rules. Or I can decide not to play the game and not participate.

We believe these options are wonderful, liberating tools for everyone. It puts a different perspective on life. Yes, there are consequences; the penalties may be stiff. I may be accused of not being a team player. But I also may serve as a pioneer to take organizations into innovative territories. It becomes possible to invent new markets, discover new ways of competing, gaining unheard of commitments. I can become a role model for higher levels of performance. I make a difference in the worlds around me.

I may be either respected or scorned for my behavior. It is my choice for what I do. I cannot control the reactions of others. But I exercise free choice and accept the consequences.

So, ask yourself these questions: Are you in the game? What is your role? What are you contributing to the project, team, and organization? How can you change the game? Are you satisfied with the status quo? Are you okay with the scoring system or should the measurement system be revised? Do you want to play this game, or do you want to find or invent a new one? Doing so requires selling the new game to others.

Sales Planning

Every activity benefits from careful planning. Planning is important to salespeople because they are the people who connect directly with customers, and their success or failure largely depends upon their sales skills. Therefore, a sales planning structure needs to be prepared carefully. Project managers go through this process when they collaborate closely with salespeople during the early stages of customer project life cycles. We highly recommend that complete project managers get involved early in selling cycles. Their presence brings subject matter expertise, credibility, and commitment to the table. They can also ward off ill-advised projects, and they get advance notice of upcoming project requirements. One may never know exactly when the sales process begins, so recognize that sales can happen at any time, and be prepared to shift into a sales mentality at a moment’s notice.

A sample structure for call planning includes a series of steps. Each step needs to be completed before moving to the next step:

1. Set an appointment for a meeting.

2. Set a meeting with the decision maker.

3. Set a meeting to present the proposal.

4. Secure the order.

5. Determine future business opportunities.

Mastering the sales planning process unlocks more sales potential quicker than any other process. Become skilled at a well-defined sales process that you can follow and learn from. Know also that a good sales process mirrors the pattern by which customers make buying decisions.

Some salespeople fail to follow a selling process that facilitates relationship building with the buyer because they do not see the importance of building relationships with buyers. Customers typically make decisions through five sequential buying decisions in the following order: salesperson, product, company, price, time to buy. So if salespeople are not dedicated to serving customers and presenting to customers what they really need, those sellers will be out of sync with buyers.

Types of Buyers

Not all buyers have the same status in the sales cycle. Here are likely ones you will encounter:

• Technical

– Make recommendation

• Economic

– Authorized to spend money

• Qualified

– Expressed interest

• Skeptical

– Not interested

Our advice is: know who you are dealing with, modify your approach depending on the potential buyer, and sell to all levels.

Questioning Skills

Questions are important tools for engaging the prospect, building rapport, discovering needs, agreeing on those needs, controlling the conversation, and managing the entire sales cycle. The best sales questions start with “what,” “why,” or “how” and are open-ended. They encourage customers to talk about issues they are facing. This gives the salesperson clues to ask deeper questions—questions about specific customer needs she can meet. Poor questioning skills lead to resistance in the form of objections later in the sales cycle and do not facilitate relationship building or company differentiation.

Best Sales Questions to Ask: Questions help customers make their first key buying decision, which is whether to “buy” the salesperson. Questions build rapport and demonstrate interest in the customer. They uncover customer needs, who to call on, the decision-making time frame, competition, and how the customer will make the decision. Research indicates that 86 percent of salespeople fail to ask the best sales questions. Poor questioning skills lead to resistance in the form of objections later in the sales cycle. This resistance will be in the form of objections to the product, price, company or salesperson.

Examples of good sales questions include:

• “What have you used in the past?”

• “How was it implemented?”

• “Why did you decide on that?”

As you ask open-ended questions to investigate customer needs, you will come upon some needs that seem to have a particular urgency. Whenever you suspect this is the case, ask a leverage question to confirm your hunch and clarify the situation. For example:

• “How has this problem affected you and your company?”

• “What are the consequences if this problem continues?”

• “How are your customers affected?”

These types of questions encourage customers to talk about gut issues they are facing. By clarifying what is really at stake with a business problem or opportunity, leverage questions increase the customer’s desire for a solution. And they let the salesperson know how to present a product as the right solution to the right issues.

If you want to be positioned as the best or only solution for your customer, ask the best questions. Customers will view you as a consultant who has their best interests in mind.

Remember that questions are the number-one tool salespeople have for:

• Engaging the prospect

• Building rapport

• Discovering needs

• Agreeing on those needs

• Controlling the conversation

• Managing the entire sales cycle

Unless you ask the right questions, you won’t understand the right problems to solve. But there’s an art to asking sales questions. We share these tips for asking more effective sales qualification questions. Based on our experiences we suggest:

1. Ask for permission before proceeding

2. Start broad, get more specific

3. Build on previous responses

4. Use industry jargon, when appropriate

5. Keep questions simple

6. Use a logical question sequence

7. Keep questions nonthreatening

8. Explain the relevance of sensitive questions

9. Focus on desired benefits

10. Maintain a consultative attitude

11. Carefully navigate transitions

12. Do not ask yes or no questions

13. When in doubt, ask, “why”

14. Ask who else you need to speak with

15. Resist the temptation to pitch your product or services until the buyer asks

Sales Process: Features, Benefits, Advantages, and Closure

The classic sales approach, applicable to almost any environment, is to cover features, benefits, and advantages (see Figure 11-1) of a product or service. Use compelling wording and arguments; do not strive for a high score on the “jargon meter.” If you know not what the customer (or stakeholder) most cares about, you may need to describe all features of your product or solution. A better approach is to focus on what the customer truly cares about. Provide details, a prototype, or a demonstration so the customer clearly understands the key features. “This project management office (PMO) addresses a key deficiency in the organization by providing a complete document management and retrieval system. Let me show you how it works ….”

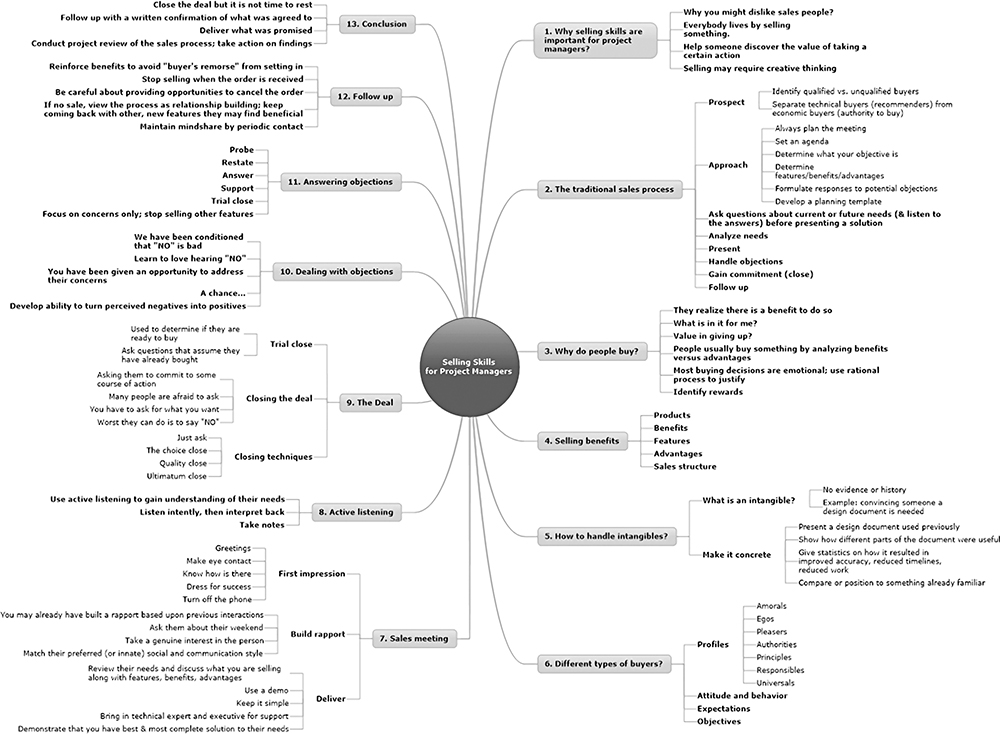

Figure 11-1: Sales Skills

Sometimes it may be beneficial to start with benefits before getting into features, as a means to engage the prospect. Describe the benefits that accrue after features are implemented. “This system relieves in-field consultants from time-consuming, low-value-added activities, provides increased quality assurance within the project delivery process through access to the most up-to-date documents, and serves as a breeding ground for knowledge sharing.”

Project how these benefits provide a competitive advantage for the organization. “Implementing this system means our customers will be served by the latest technology with error-free documentation, leading to more repeat business, and field consultants can spend more time addressing both existing and new customer requirements and turning them into sales.” Steps in the selling process include:

1. Use management-speak when talking with upper managers.

2. Clearly identify the problem.

3. Present a compelling argument about how features will produce benefits.

4. Cover the advantages of this approach.

5. Prompt and listen for feedback.

6. Close and get the order.

HOW TO SELL A PROJECT TO AN EXECUTIVE: LESSONS LEARNED

Depending on the culture of the company, a project manager will sell his or her ideas (potential projects) to the people who finance them using an oral presentation or a written report. These proposals need to be clear and concise.

Usually, the audience will be very busy people. If you’re not getting into a specific topic quickly, they can lose their patience and disconnect. To communicate with your audience, use terms that management understands.

A best practice is to follow the advice of a veteran sales professional to sell benefits, not features. Put emphasis on financial benefits, on issues such as greater security, greater efficiency, or greater morality associated with the implementation of the idea.

We suggest the following steps:

1. Sum up the idea.

2. Define the need for the idea—that is, explain what problem will be solved.

3. Explain how the idea will generate money for the company. Are there other benefits also?

4. Define the necessary resources. What will it take to develop and commercialize the idea? How much money will it cost? How long will it take?

5. Ask for commitment from the sponsor. Get a follow-up after the presentation to get funding for the idea.

STEP 1: SUMMARIZE THE IDEA

Write a concise summary of your idea or future project. That brief statement will help others to remember it easily and accurately. Use this overview to begin a written proposal. Also practice and measure the time that it takes to present it. Be able to describe the idea in less than one minute.

STEP 2: DEFINE THE NEED FOR THE IDEA

No sense posing an idea unless it meets a market need. The best way to demonstrate that there is a need is to collect phrases from potential clients. Cite references from credible strategic consultants. Put on the table that the company can benefit from that investment. In any proposal, written or oral, a summary of the need for the idea should immediately follow a summary of the idea.

STEP 3: EXPLAIN HOW THE IDEA WILL MAKE MONEY FOR THE COMPANY

Understand and describe to the audience how the idea will generate benefits for the organization. Usually the solution to the problem should fit with the way in which the organization produces and sells products and/or services. This does not mean that one cannot sell an idea that dramatically transforms an organization. However, the financial benefits of adopting the idea need to be very large.

STEP 4: DEFINE NECESSARY RESOURCES

Before deciding whether or not to approve the idea or project, executives need to know what resources are necessary to make the idea or project bear fruit. The key to the idea is if the organization has the resources to develop and market it. Even if it does, other projects may be competing for the same resources. If the organization does not have the necessary resources, all is not lost if you propose an alliance with another company or another business unit that can supply the resources that the company lacks.

STEP 5: ASK FOR COMMITMENT FROM THE SPONSOR

Clarify what is the next step. This includes funding, personnel, logistics, person-hours, and the time needed to implement the idea. Depending on the scope of the idea, you may need to hire new staff, obtain new equipment, or launch a pilot project. Get explicit commitments.

CONCLUSIONS

• You may discover that you need to sell an idea or project in stages.

• Be persistent in an educated manner until you get a yes or a no. Prepare for displeasure. Sometimes a no is the right answer.

• Today is a good day to try it because tomorrow will be better when you sell your idea.

Dealing with Objections

Many people dread the inevitable moment when clients, customers, or executives raise questions or concerns about the proposed project. In reality, the opposite ought to be true. These objections are wonderful gifts given to you! Now you know what it takes to win the sale or get a commitment. Without this valuable information, you have to keep pitching all features, hoping something captures the customer’s interest. Objections open the door to win the sale—all you have to do is address them.

I (Bucero) was part of a team from a multinational firm preparing a project proposal for a telecom company in Spain. We worked on the proposal for two weeks, based on the RFP from the customer. Some of the information was not clear enough for me, but salespeople from the seller organization did not allow us to meet the customer in order to clarify it. So we prepared our project proposal approach focused on our understanding of the RFP. Then we sent our proposal to the customer, and he invited us to defend our proposal. When we started the presentation, our customer started to make some objections. At the beginning, we tried to reinforce our points to win the proposal, but some minutes later we understood that we were lucky because we discovered that we had misunderstood several key things that would be crucial for project success. The customer’s objections made us ask more concrete questions. We finally decided to rewrite our project proposal.

Make it a point to ask for questions and issues about the proposal. Listen carefully, and ask clarifying questions, to understand what is at the core of each issue. Address these objections with full honesty if you have an answer. If the issue needs additional work or research, state what process you will use to address the issue. Then make a mutual commitment for a future time when you can engage in further dialogue. The process at work here is to turn negative perceptions into features through innovative responses that support both your personal and organizational integrity as a solution provider.

Presentation Skills

For many salespeople, and potential customers, sales presentations are nothing more than data dumps. Talking too much, presenting too soon, and just winging it on sales calls have grim consequences: lost momentum, stalls and objections, lost sales, extended sell cycles, margin erosion, and no clear path to improvement. Bottom line: an entire sales career can be mediocre at best without a clear road map to follow that sets up the sales presentation at the right time—when the customer wants to hear it. After delivering each presentation, analyze what was good, what was not so good, and what should be improved for your next presentation.

GAINING COMMITMENT

The principal mission of the salesperson is to gain commitment. That is why companies value the work salespeople do. To effectively capture a customer’s commitment, determine the objectives for every sales call at the beginning. When all features, benefits, advantages, questions, and objections have been covered, get closure by asking for the order. Ask all key stakeholders to make explicit commitments to a course of action. Get them to nod their heads in public or sign a virtual or symbolic “contract.” Many presentations, proposals, or sales calls fail to produce desired outcomes simply because the salesperson did not achieve closure. This is not a time to be timid. Follow-through is important. Even casual requests for information or support benefit from clarifying what and when the work will be done. As human beings we are almost hard-wired to do things we said we would do, but if no one asks us to commit, we are happy to “do what we can,” with no guarantee of completion or priority. Do not drop the ball. Ask for clear commitments on as much of the work as possible.

Once you receive the order, stop selling! Many a sale has been lost when more information is conveyed that then triggers doubt or concerns by the buyer—also known as buyer’s remorse.

PRACTICE

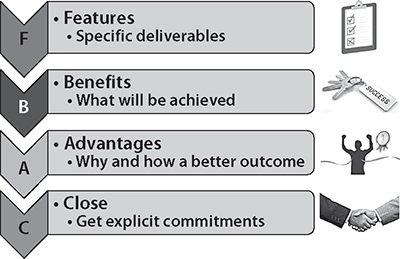

As an experiment during our PMI seminars, we wanted to determine if project managers who claimed poor sales skills could, after a short introduction to the sales process, put together decent sales proposals. We covered why, what, and how the sales process works—features, benefits, advantages, and close. Then we gave each table a short period of time to prepare a sales presentation. The topic we suggested was selling The Complete Project Manager concept and seminar to managers in their organizations, since this was a topic they all had in common as a consequence of participating in the seminar. The exercise would also serve to prep them for reporting back to their managers about what they learned and what was covered.

We were amazed that they rose to the challenge. All elements were covered extremely well, and feedback from facilitators and other participants helped to reinforce key points and elaborate on missing elements. Each table applauded presentations by other tables. It goes to show that knowledge and practice develop crucial skills that had been dormant or missing.

Figure 11-2: Sales Examples

Figure 11-2 depicts flip chart examples of these sales presentations.

Proposal Preparation

Project managers may be called upon to prepare customer proposals, commonly referred to as RFPs (request for proposal) or RFQs (request for quotation) or even RFIs (request for information). This is usually a huge challenge, mainly because there is not enough time to interact with customers during proposal preparation. That situation leads to many assumptions that may affect the quality of the proposal and, in turn, the future project. The goal is to develop winning project proposals. Proposals are the basis for starting projects. Successful proposals are well planned, well written, cohesive, and competitive.

Proposals may be addressed to external or internal customers. All proposal efforts of any size have a proposal leader and a proposal team. The temporary nature of the proposal team requires that the proposal leader be able to quickly assemble and motivate the team. Communicate to the proposal team the need for the proposal and its importance to the organization.

A proposal tells the potential customer how you will achieve their requirements or needs. Winning a contract from any proposal requires a dedicated effort to develop the document for delivery to the potential customer. Successful proposal development requires discipline. The most difficult thing to do well in a proposal is to convey the proper message and commitment to perform the work. Involve the best specialists from all required areas to prepare the proposal. The proposal leader needs to ensure that all necessary tasks have a qualified person assigned to write a portion of the proposal. Develop a schedule for proposal work to ensure all critical dates are met. The schedule is very important to ensure that the proposal is delivered to the customer on time. In our experience, most times, proposal team members are pressed because of lack of time. This opens the door for mistakes or omissions. Plan tasks and time for proposal editing to detect any mistakes.

The strategy we suggest to win a contract is:

1. Understand customer requirements and needs.

2. Know and analyze the offer from your competitors.

3. Assess what your organization can offer.

4. Make a decision about how to shape your proposal for the highest probability of winning.

PROPOSAL CONTENT

When preparing large and complex proposals, it is more convenient to do so step by step. Proposals usually address three areas for the customer:

• What are you going to do?

• How are you going to manage it?

• How much will it cost?

The main components of a proposal are:

• Executive summary. Highlights key aspects of the proposal. It is similar to a project objectives statement that states what work you are doing, why, how, and how much it costs.

• Technical. A description of the work to be accomplished and the procedures to be used to do the work.

• Management. The proposed method to manage the project work and the necessary information required to establish supplier credibility. This portion demonstrates that you have managed similar projects before.

• Pricing. Proposed bid price and proposed terms and conditions.

Depending on the magnitude of the project, those components may be integrated in only one document or in separate documents, one each for the technical, management, and pricing portions of the proposal, along with an overview and summary.

The technical component addresses the actual details of what is being proposed. The usual sections that are included are:

• Statement of the problem

• Technical discussion

• Options considered and how selected

• Project plan

• Task statement

• Summary

• Appendices

The management component addresses the details of how the project will be managed. The usual sections included are:

• Introduction

• Project management approach

• Organization history

• Administrative information

• Past experience

• Facilities

• Summary

The pricing component is concerned with the details of the costs for the project and the proposed contractual terms and conditions. The usual elements include:

• Introduction

• Pricing summary

• Supporting details

• Terms and conditions

• Cost estimating techniques used

• Summary

THE PROBLEM TO SOLVE

The most important part of any sales or proposal development effort is identifying and understanding the problem that the customer wants you to solve. The way you present your understanding of the problem and the project you are proposing to solve it is critical to convincing the customer that you fully comprehend their concerns and that your proposal is the best one. Resistance will certainly arise if the customer does not agree with or understand the same problem. It is essential that your explanation is factual, convincing, and accurate. Identifying the wrong problem or providing a subjective opinion will not convince the customer that your proposal is the best solution.

Descriptions of problems and solutions usually involve:

• Nature of the problem

• History of the problem

• Characteristics of the optimal solution

• Alternative solutions considered

• Solution or approach selected

THE SALES PROCESS FOR PROPOSALS

Depending on the industry, the country, and the organizational culture, the length of the sales process can vary, but in general, the process comprises the following steps:

1. Presales

2. Gathering requirements

3. Proposal preparation

4. Proposal negotiation

5. Signing of the contract

SALES PRESENTATIONS

The complete project manager needs to develop skills in making sales presentations. Although some project managers have a natural ability to present, most need training and to acquire some presentation experience. One very effective way to do this is for the project manager to work with a mentor who has strong sales presentation skills.

Proposal presentations are always different, and special efforts are required to adapt them to the customer environment, organization, and situation. This requires time and courage. It is critical for the proposal presenter to transmit enthusiasm to the customer and to build confidence and trust. Demonstrate commitment to the customer’s best interests. To increase your chances of success, sequence your presentation to follow the decisions the customer will make. This is exactly how professional salespeople orchestrate their sales calls. As the buyer–seller relationship grows, the relationship becomes one of the differentiating factors that leads to more successful outcomes.

Remember that these skills require practice, passion, persistence, and patience. They cannot be gained overnight.

Case Study

I (Englund) was assigned as program manager to coordinate a massive proposal for a major account to update their systems and OEM computers using us instead of a competitor. We gathered lots of information from the customer engineering manager about technical requirements, including custom modifications that would be necessary.

Normally, our company was not interested in developing custom solutions, since we were a hardware vendor selling off-the-shelf systems. The size of this deal, however, made us take notice. To further promote that interest, I arranged interviews with the division general manager, manufacturing manager, specials engineering manager, and headquarters sales manager. I brought the field district manager, sales representative, and systems engineer into the factory to personally meet with these key managers. These person-to-person meetings ensured that everybody knew what was happening and that we could go ahead with the proposal, knowing in advance that all managers who would have to approve it were supportive.

The requirements were challenging, so we worked as a team to develop a solution. We summarized our understanding of the requirements, and then covered the technical aspects, support, qualifications, company commitment, and pricing. I brought in an editor to proofread the long proposal. A graphic artist created a cover page and presentation slides highlighting a half-dozen key aspects of the proposal. I drafted a letter that the CEO signed, expressing executive commitment to the deal. I also crafted a script for the presentation and briefed the group general manager (later to become the company CEO), who would join us in the presentation. We booked the corporate jet for our journey to the customer site.

I advised the sales rep to call on the customer general manager, who in essence would be the economic buyer, in addition to the technical recommenders with whom he regularly meets. This is an application of “selling at all levels.” I suggested the meeting to mitigate the possible risk that the general manager would be surprised or ill-informed about a large appropriation request coming across his desk. But the meeting I suggested did not happen; the sales rep received comments from the engineering departments that their inputs were sufficient. However, this is rarely the case. The meeting should have happened. We may have also gotten better information about the market and the customers’ future business.

All participants did an excellent job in presenting the proposal. They appeared as an integrated, well-coordinated team. The group general manager was especially effective, reinforcing the highlighted script along with adding personal touches—for example, saying, “I come with the full commitment of the CEO and my own to working with you as a partner.” The customer reaction was “You blew our socks off!” since the proposal far exceeded their expectations.

This experience underscored for me the importance of orchestrating a thorough involvement of all key players in a sales process. Meeting face to face, sharing possibilities and enthusiasm, and demonstrating how a solution would work were important factors. I have since used this process many times and codified the steps in an action sheet. It works every time!

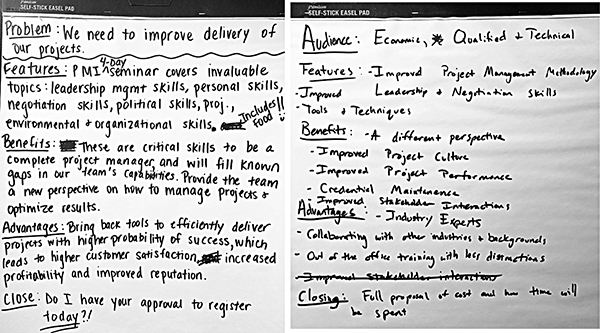

Figure 11-3: Selling Skills for Project Managers

As a coda to this story, our company did not get this business, simply because the customer experienced a deep downturn in its business right about that time and had to cancel its upgrade plans. We also realized that, both in this example and in general, there comes a time to stop selling.

Not all efforts, even those backed by best intentions and execution, turn out successful. But the process was still regarded as a superb effort and successful project. I wrote a letter to the approximately eighty stakeholders who participated and thanked them for their contributions. We had succeeded as an organization in how we applied sales best practices and learning for all involved in a large program.

MINDMAP OF SELLING SKILLS

Figure 11-3 puts all elements of the PM selling process into one picture.

Summary

A key challenge facing many project, program, and portfolio managers is selling the value of their services and processes. Learning and embracing tenets of the sales process is necessary. Follow a selling process that facilitates relationship-building with buyers. In any new endeavor or purchase, buyers want to be “sold.” Buying is usually an emotional response, followed by rational reasoning to justify the decision. Building relationships is crucial to this process. Treat all stakeholders as potential buyers of your services. Be dedicated to serving customers, and present to customers what they really need. Describe your ability to meet customers’ needs for a product or service.

Probe for issues through carefully crafted, open-ended questions. Speak in their language. Be an excellent “player” in the “game” of sales. Sell to all levels in an organization, taking a holistic approach to the challenge. View objections as opportunities to “win the sale”; when buyers object, they are engaged and sharing what they really need.

Building a convincing proposal is a disciplined process. Proposals follow a general format composed of three components: technical, management, and pricing. The format provides a structure for describing your ability to meet the customer’s needs for a product or service. We believe winning proposals are written by competent professionals and a motivated team.

Know that you are continuously in sales cycles throughout project life cycles. Do not be a victim of lost sales or opportunities. Integrate sales skills with all other skills covered in this book. Embrace the sales process as the means to secure necessary commitments, in a genuine manner worthy of a complete project manager.