1

Leadership and Management Skills

Leadership is not about creating followers only. It’s about developing and creating new leaders. I feel good when I’m able to create a leadership spirit in my team.

—RANDALL L. ENGLUND AND ALFONSO BUCERO

In this chapter, we cover leadership and management skills—those vital visionary and “can do” competencies so necessary for people in a position to influence colleagues, team members, upper managers, clients, and others. The complete project manager possesses charisma, teachability, respect for self and others, qualities of leadership, and courage, as well as lead-by-example, delegation, listening, and relationship-building skills. He or she has to interact with people and achieve results. Ethical behavior is critical.

Leading versus Managing

We start by highlighting, in Table 1-1, the activities performed when leading or managing a team. Many debates ensue around differences between leadership and management. Our position throughout this book and in our seminars is that both are necessary. Project managers tend to view their jobs as managing. We believe complete project managers also need to be leading.

Table 1-1. Project Manager Activities

| Leading a Team | Managing a Team |

| Setting a direction: Creating a vision of the project, with implications for the roles and contributions of team members | Planning and budgeting: Developing a plan for the project, including objectives, critical path, milestones, and resources needed |

| Aligning people: Seeking commitment by communicating and interpreting the vision together and translating the roles and potential contributions into expectations for team members | Organizing and staffing: Determining the tasks, roles, and responsibilities required for the project; assembling individuals with appropriate knowledge, skills, and experience |

| Influencing and inspiring: Encouraging and assisting individuals to actively participate by establishing open and positive relationships, by appealing to their needs, values, and goals, and by involving, entrusting, recognizing, and supporting them | Controlling and problem solving: Monitoring and evaluating the progress of the team through observation, meetings, and reports; taking action to correct deviations from the project plan |

In some cultures, people do only what has been defined as their responsibility. Consider the following joke:

Long, long ago, a soldier was shot in the leg in battle and suffered from constant pain. An officer in the troop sent for a surgeon versed in external medicine to treat the soldier’s wound.

The surgeon came to have a look, then said, “This is easy!” He cut off the arrow shaft at the leg with a big pair of scissors and immediately asked for fees for the surgical operation.

“Anyone can do that,” the soldier cried. “The arrowhead is still in my leg! Why haven’t you taken it out?”

“My surgical operation is finished,” said the doctor. “The arrowhead in your leg should be removed by a physician who practices internal medicine.”

Project team members may likewise view their roles very narrowly. Professional project managers usually know what their responsibilities are, but in our experience, there have been many occasions in which the project manager needs to take action beyond the norm in order to get activities done. We recommend that project managers stay flexible and adaptable. In some cultures, the project manager needs to lead by example and wear different hats, especially when people are blocked by perceived limitations in their job descriptions.

RECIPE FOR SUCCESS

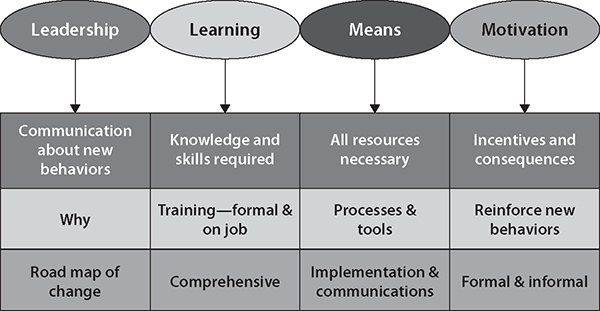

A recipe for repeatable, sustainable success on all endeavors is to find areas where small efforts applied in the right places lead to large impact, much like a ship’s helmsperson easily turns a wheel that turns a small trim tab that uses water pressure to turn a large rudder. We believe the answer is L2M2—two Ls and two Ms (see Figure 1-1):

Leadership is a well-articulated communication across the organization of what kind of new behavior is required and why it is required, along with a road map of the change that will take place over time.

Learning is the process of supplying the knowledge and skill necessary for individuals to carry out new behaviors. It includes learning support from the PMBOK Guide, project leadership, business skills, and so on. In the case of portfolio management, it includes role-based knowledge and skill for all aspects of the process. This starts with project selection and proceeds to the end of the project outcome life cycle.

Means are all the resources necessary to carry out the behaviors, including tools, organizational policies and structures, and time. For portfolio management, this includes but is not limited to a prioritization and selection process, an implementation and update process, a supportive organization design, software-based tracking tools, and information systems.

Motivation is the formal and informal system of incentives and consequences that reinforce new behaviors. These are differentiated by role so that the required role-based behaviors are supported in all parts of the organization.

Behavior begins to change when all four factors work in concert. Without leadership, people will not know how to apply their new knowledge and skill in concert with business strategic and tactical objectives. Without learning, people may know what they are supposed to do from leadership, but not know how to do it. Without means, people may know what to do and how to do it, but not have the tools and resources to carry it out. Without motivation, people may know what leaders want, know how to do it, and have the resources to carry it out, but simply not bother to do it.

Figure 1-1: L2M2 Recipe

Putting efforts to ensure these four elements are in place, efficiently and effectively, is a good recipe to follow.

START BY LEADING YOURSELF

Have you ever worked with people who did not lead themselves well? Worse, have you ever worked for people in leadership positions who could not lead themselves? We have, and in those situations, we felt very bad, unsupported, and disappointed.

These people are like the crow in a fable that goes like this: A crow was sitting in a tree, doing nothing all day. A small rabbit saw the crow and asked him, “Can I also sit like you and do nothing all day long?” “Sure,” answered the crow, “why not?” So the rabbit sat on the ground below the crow, following his example. All of a sudden, a fox appeared, pounced on the rabbit, and ate him.

The tongue-in-cheek moral of the story is that if you are going to sit around doing nothing all day, you had better be sitting very high up. But if you are where the action is, you cannot afford to be sitting around doing nothing. The key to leading yourself well is to learn self-management. We have observed that many people put too much emphasis on decision making and too little on decision managing. As a result, they lack focus, discipline, intentionality, and purpose.

Bill George, former chairman and CEO of Medtronic and a professor at Harvard Business School, says in his material on “True North” (2015):

• Lead yourself first

• Become an empowered leader

• Get in touch with your emotional intelligence

• Reframe who you are

• Be true to your values

Successful people make right decisions early and manage those decisions daily. Some people think that self-leadership is about making good decisions every day, when the reality is that we need to make a few critical decisions in major areas of life and then manage those decisions day to day. Where we seldom have all or enough information to make truly “right” decisions, it is usually better to make some decision and then monitor progress. Be the leader who makes command decisions. If new information later appears that calls for different actions, be willing to make the change … and communicate why.

Here is a classic example. Have you ever made a New Year’s resolution to exercise? You probably already believe that exercise is important. Making a decision to do it is not hard, but managing that decision and following through is much more difficult. Let us say, for example, that you sign up for a health club membership the first week of January. When you sign on, you are excited. But the first time you show up at the gym, there is a mob of people. There are so many cars that police are directing traffic. You drive around for fifteen minutes and finally find a parking place four blocks away. But that is okay; you are there for exercise anyway, so you walk to the gym.

Then when you get inside the building, you have to wait to get into the locker room to change. But you think that is okay. You want to get into shape. This is going to be great. You think that until you finally get changed and discover all the exercise machines are being used. Once again you have to wait. Finally, you get on a machine. It is not the one you really wanted, but you take it and you exercise for twenty minutes. When you see the line for the shower, you decide to skip it, take your clothes, and just change at home.

On your way out, you see the manager of the club, and you decide to complain about the crowds. She says, “Do not worry about it. Come back in three weeks, and you can have the closest parking place and your choice of machines. By then, 98 percent of the people who signed up will have dropped out!”

It is one thing to decide to exercise. It is another to actually follow through with it. As everyone else drops out, you have to decide whether you will quit or stick with it. And that takes self-management.

Nothing will make a better impression on your leader than your ability to manage yourself. If your leader must continually expend energy managing you, then you will be perceived as someone who drains time and energy. If you manage yourself well, however, your leader will see you as someone who maximizes opportunities and leverages personal strengths. That will make you someone your leader turns to when the heat is on. I (Englund) had a colleague who seemed to constantly irritate our manager. In contrast, I made it a point to always help the manager and be easy to work with. In turn, that manager took good care of me.

The question is: what does a leader need to self-manage? To gain credibility with your leader and others, focus on taking care of business as follows:

• Manage your emotions. People driving in a state of heightened emotions are 144 percent more likely to have auto accidents. The same study evidently found that one out of five victims of fatal accidents had been in a quarrel with another person in the six hours preceding the accident. It is important for everybody to manage their emotions. Nobody likes to spend time around a person who behaves like an emotional time bomb that may go off at any moment. But it is especially critical for leaders to control their emotions because whatever they do affects many other people. Good leaders know when to display emotions and when to delay doing so. Sometimes they show them so that their people can feel what they are feeling. It stirs them up. Is that manipulative? We do not think so, as long as the leaders are doing it for the good of the team and not for their own gain. Because leaders see more than and ahead of others, they often experience the emotions first. By letting your team know what you are feeling, you are helping them to see what you are seeing.

• Manage your time. Time management issues are especially tough for people in the middle. Leaders at the top can delegate. Workers at the bottom often punch a time clock. They get paid an hourly wage, and they do what they can while they are on the clock. Leaders in the middle, meanwhile, feel the stress and tension of being pulled in both directions. They are encouraged, and are often expected, to put in long hours to get work done.

• Manage your priorities. In some companies, project managers have no choice but to juggle various responsibilities. But the old proverb is true: if you chase two rabbits, both will escape. So, what is a leader in the middle to do? Since you are not the top leader, you do not have control over your list of responsibilities or your schedule. A way to move up from the middle is to gradually shift from generalist to specialist, from someone who does many things well to someone who focuses on a few things she does exceptionally well. Often, the secret to making the shift is discipline. In Good to Great, Jim Collins (2001) writes, “Most of us lead busy, but undisciplined lives. We have ever-expanding ‘to do’ lists, trying to build momentum by doing, doing, doing and doing more. And it rarely works. Those who build the good-to-great companies, however, made as much use of ‘stop doing’ lists as the ‘to do’ lists. They displayed a remarkable amount of discipline to unplug all sorts of extraneous junk.”

• Manage your energy. Some people have to ration their energy so that they do not run out. Up until a few years ago, that was not me (Bucero). When people asked me how I got so much done, my answer was always, “High energy, low IQ.” From the time I was a kid, I was always on the go. I was six years old before I realized my name was not “Settle Down.” Now that I am older, I do have to pay attention to my energy level. Here is one of my strategies for managing my energy. When I look at my calendar every morning, I ask myself, “What is the main event?” That is the one thing to which I cannot afford to give anything less than my best. That one thing can be for my family, my employees, a friend, my publisher, the sponsor of a speaking engagement, or my writing time. I always make sure I have the energy to do it with focus and excellence.

• Manage your thinking. The greatest enemy of good thinking is busyness. And middle leaders are usually the busiest people in an organization. If you find that the pace of life is too demanding for you to stop and think during your workday, then get into the habit of jotting down the three or four things that need good mental processing or planning that you cannot stop to think about. Then carve out some time later when you can give those items some good think time.

Are You Delegating Properly?

Although a project manager cannot delegate everything in a project, delegating can make a complete project manager’s life easier. But many are hesitant to pass on responsibilities. For example, many organizations have a low project management maturity level, and management’s focus is on project results, not on project control.

Most project managers do not have enough authority and so they also perform a technical role along with their project management role. Many of them have been promoted from technical positions to project management positions. As individual contributors, they were not accustomed to delegating work to others; they did their technical tasks and just followed the project plan. Now, as project managers, they do not feel comfortable delegating because they are not confident in the people on their team, and nobody has explained to them why and how to do it. Here are some reasons people share with us why they do not delegate:

• It is faster to do the job myself.

• I am concerned about lack of control.

• I like keeping busy and making my own decisions.

• People are already too busy.

• A mistake by a team member could be costly for my project.

• Team members lack the overall knowledge that many decisions require.

To be able to delegate, you need to be conscious that you have a team, that you have people who can help you achieve project success. You cannot achieve project success alone; you need people. Many of the people we have talked with are managing more than one project and juggling a mix of technical and project management tasks. All the answers above make sense, but the real reason for failure to delegate often comes down to deep insecurity. This self-defeating attitude influences how you accept and recognize the performance of those who work under you.

Do not think of delegating as doing the other person a favor. Delegating some of your authority only makes your work easier. You will have more time to manage your project, monitor team members, and handle conflicts. Your organization will benefit, too, as output goes up and project work is completed more efficiently.

Leading by Example

Leading properly most often means leading by example. A colleague and former executive project manager at IBM Research, Jim De Piante, PMP, shared this personal example with us:

Early on in my career as a project manager, I learned a valuable lesson, one which has served me well ever since. I didn’t learn this lesson acting in a project management capacity. Rather, I learned it on the football field, in the capacity of youth football coach.

On my first day as coach, I came out to the team’s first practice. I got there on time, armed with a whistle, a patch that said “coach” on it, a clipboard, and a practice plan.

I hadn’t played any organized sports as a kid and really wasn’t clear on what a coach was supposed to do. I imagined, however, that the most important thing for me to do would be to establish myself as the coach, the person in charge, so that the boys would have an unambiguous understanding of from whom they were to take direction. I saw this as the only way to knit them together into a team, which I speculated would be the essential ingredient in getting them to win matches.

I didn’t hesitate to make it clear that the reason we were playing the game was to win matches, and that to do that would take teamwork, discipline, and commitment. As practice began, I had a clear idea of what I wanted to do, what I wanted them to do, and why. I communicated these things to them in direct, simple, and unambiguous ways.

What happened as a result surprised me a bit. It shouldn’t have, but it did. The boys, and their parents, followed my lead. They did what I asked them to do. The not-so-surprising consequence of this was that we began to have a certain success, which is to say, the boys played well together and won matches. As they succeeded, they came to trust more and more in my judgment and leadership and followed my direction all the more, with the delightful consequence that they continued to play even better together and win even more difficult matches.

In one of those unforgettable life lessons, I realized that the first cause of all success was my willingness to act as their leader. It was what they expected of me, and because I had met their expectations, they were all too happy to meet mine. Their success as a team was the result.

I was dealing with six-year-old boys. Taking on the role of leader, and acting the part decisively, wasn’t so hard. On the other hand, at work, on my projects, I had imagined that it might seem too bold of me to “take charge,” and that the wonderfully talented technical professionals on my team wouldn’t want me to act decisively as their leader—that they would resent it.

I was wrong.

My experience on the football field caused me to rethink my views. I came to understand leadership as a service to the people I was leading—that leadership was the critical ingredient in a team’s success, and it was mine to provide. I reasoned that, in the same way that it was crucial to the football team’s success that I accept and fulfill my role as team leader, it would be crucial to my project team’s success that I do likewise. They expected me to be the leader and to accept all the responsibility that that implies. This was, in fact, my duty to them, and to do otherwise was to cheat them of their due.

For them to come together as a team and do their best work required the influence and organizing principle of a leader. To take charge was simply to fulfill their expectation of me. And what they expected of me was to create the circumstances under which we could succeed. There was no one else on the team positioned to do that, which means they depended on me for it.

I was right.

Lesson learned.

Managing Your Executives

Complete project managers with the ability to communicate well—especially when addressing executives and project sponsors—always have an advantage. Good communication skills are especially handy when dealing with executives who believe they do not need to know much about projects or the project management process because “that’s the project manager’s responsibility.” It is generally true that project managers take great care of the projects they manage, and executives and senior managers take care of business results and monitor overall business success. But when each of these groups wants to be understood, they need to speak the language the other group understands. Managers, in general, do not care about technical terms—they take care about results, objectives, ROI. It is difficult to put yourself in the shoes of your boss, and it is also difficult for your boss to understand your problems as a project manager.

Several years ago, I (Bucero) worked in Spain for one of the largest multinational companies in the world. I managed an external customer project with a €10 million budget, 150 workers, and four subcontractors. During the project’s two-and-a-half-year duration, my senior manager visited the customer only once, and while I met with him monthly, our project status reviews never lasted more than ten minutes. This manager expressed very little interest regarding the problems I found while managing the project.

This type of counterproductive behavior is starting to change in southern Europe. As project management awareness grows in organizations, executives are coming to understand the importance and necessity of planning before implementing activities. And who knows more about people, organizational abilities, and what it takes to implement a project than a project manager?

Executives need project managers to implement strategy. Project managers can align themselves with executives by finding and focusing on these commonalities:

• Ultimately, project managers and executives share the same organizational objectives because they work for the same company.

• Because more than 75 percent of business activities can be classified as projects, project managers and executives arguably have the same impact on business operations and results.

• The experiences and education of project managers give a company a competitive advantage; wise executives find ways to use the experiences of the individuals in their organization to gain an upper hand.

• Executives and project managers both must learn to navigate political climates successfully to ensure results.

Even with these similarities, executives know only one part of the story. They miss a great deal of insight that comes from dealing with the customer, which is something project managers do much of the time. Unfortunately, project managers often talk to their upper managers only when they run into problems, and executives do not speak enough with project managers because they perceive them simply as the “doers.” In this paradigm, opportunities for project managers and executives to act as partners are lost, and many organizations fail to grasp multiple opportunities to become more profitable and successful through project management practices.

So many organizations tend to focus on project manager development as it correlates to improving project results, but what about educating executives? There is value in teaching executives about a project’s mission, implications, and desired effects, as the end product of such education is more clearly defined roles and better relationships with project managers.

Complete project managers need to know, understand, and communicate their value to the organization. Do not wait until executives and project sponsors ask you about your project’s status. Take action—sharing both good and bad news—and seize opportunities to talk about project work, being persistent and patient along the way.

Integrate Leadership Roles that Make a Difference

THE ROLE OF CHARISMA IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

In our experience as project managers, we have realized the importance of charisma, the ability to attract others. Most people think of charisma as something mystical, almost indefinable. They think it is a quality that we either are or are not born with. But that is not necessarily true. Like other character traits, charisma can be developed. As a complete project manager, you need to draw people to work with you, so you need to be the kind of person who attracts others. These tips can help you develop greater charisma.

• Love life. People enjoy working with project managers who enjoy life. Think of the people you want to spend time with. How would you describe them? Grumpy? Bitter? Depressed? Of course not. They are celebrators, not complainers. They are passionate about life. If you want to attract people, you need to be like the people you enjoy being with. When you set yourself on fire, people love to come and see you burn.

• Put a “10” on every team member’s head. One of the best things you can do for people, which also may attract them to you, is to expect the best of them. When rating others on a scale of 1 to 10, putting a “10” on everyone’s head, so to speak, helps them think more highly of themselves—and of you.

• Give people hope. Hope is the greatest of all possessions. If you can be a person who bestows that gift on others, they will be attracted to you, and they will be forever grateful.

• Share yourself. People love leaders who share themselves and their life journeys. As you lead people, give of yourself. Put a personal touch in the stories you share with others. Share wisdom, resources, and even special occasions. We find that is one of our most favorite things to do. For example, I (Bucero) went to an annual dancing festival in Tenerife. It was something I had wanted to do for years, and when I was finally able to work it into my schedule, my wife and I took one leader of my staff and his girlfriend. We had a wonderful time, and more important, I was able to add value to their lives by spending special time with them.

When it comes to charisma, the bottom line is other-mindedness. Leaders who think about others and their concerns before thinking of themselves exhibit charisma. How would you rate yourself when it comes to charisma? Are other people naturally attracted to you? Are you well liked? If not, you may have one or more of the following traits that block charisma:

• Pride. Nobody wants to follow a leader who thinks he is better than everyone else.

• Insecurity. If you are uncomfortable with who you are, others will be too.

• Moodiness. If people never know what to expect from you, they stop expecting anything.

• Perfectionism. People respect a desire for excellence but dread totally unrealistic expectations.

• Cynicism. People do not want to be rained on by someone who sees a cloud around every silver lining.

If you can avoid exhibiting these negative qualities, you can cultivate charisma. To focus on improving your charisma, do the following:

• Change your focus. When talking with other people, how much do you talk about yourself? Be more focused on others.

• Play the first-impression game. The next time you meet someone for the first time, try your best to make a good impression. Learn the person’s name. Focus on his or her interests. Be positive and treat that person like a “10.” If you can do this for a day, you can do it every day. That will increase your charisma overnight.

• Share yourself. Make it your long-term goal to share your resources with others. Think about how you can add value to five people in your life this year. Provide resources to help them grow personally and professionally and share your personal journey with them.

Improving your charisma is not easy, but it is possible. Stay positive—remember that today is a good day!

EMPATHIC PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project manager and author Brian Irwin started the following discussion of empathic project management on blog.ProjectConnections.com (Irwin 2011):

Empathy is the ability to put one’s self in the shoes of another and to identify with what the other person is feeling. Meaningful human relationships are based on empathy, which is built through demonstrating vulnerability. By empathizing with another individual, you are demonstrating your willingness to connect with someone on a basic human level. Perhaps more than any other, the act of showing empathy for another person in the workplace has the power to transform interpersonal relationships and increase understanding.

The reality of today’s workplace does not necessarily make it easy for managers to practice empathy. A significant amount of the operational responsibilities required for running a business have been placed squarely on the shoulders of management, leaving little time for practicing empathy. The irony is that a substantial portion of this added operational responsibility is due to reduced levels of employee engagement. For project managers and leaders with direct reports, empathy is not an option. It is mandatory and critical.

One particular manager I worked with was so inadequate at empathizing with others that his entire team, consisting of nine direct reports, had turned over within a year. Six individuals found positions within the same organization and three had left the company. Several other managers in the organization also had very high turnover rates. Repeated requests for vacation time were denied and sick time would have to be supported with a note from the employee’s doctor. This is not the behavior that should be modeled by someone in a position of authority who is supposed to be leading a team of professional adults to success. Each of these individuals was capable of making adult decisions. Repeated apathetic displays proved to be intolerable to those reporting to him. The most incomprehensible atrocity is that this manager was later promoted into another position because of his support of company policy and procedure. Talent was literally “walking out the door,” but he was doing things by the book.

Tricia: This is great! It’s sad that common sense such as this needs to be written out for people to see. I guarantee you that the manager you described who got a promotion for following company policies, even though turnover in his department was abnormally high, will not continue to succeed. Without people skills and the ability to motivate his employees, this manager will eventually fail. I know, because I used to work for such an individual and within a year of me leaving that company, he was let go. The company learned that without his team, this manager couldn’t function. Keep up the great work!

Brian: Thank you for noticing the common sense in what I wrote. Experience has taught me that, much like common courtesy and common knowledge, common sense is anything but common. You are also correct in your assertion that the manager in question would not continue to succeed. Approximately 8 months after his promotion, he was terminated. The exact reason(s) is/are unknown, but suffice it to say that his lacking people skills probably had a very large role in his undoing.

PROJECT MANAGER TEACHABILITY

At the beginning of silent film star Charlie Chaplin’s career, nobody predicted his great fame. Chaplin was successful because he had great talent and incredible drive. But those traits were fueled by teachability. He continually strove to grow, learn, and perfect his craft. Even when he was the most popular and highest-paid performer in the world, he was not content with the status quo.

We likewise need to keep growing and learning as project managers and practitioners. If you observe team members and other project stakeholders, you can learn something new every day. Even judgment improves by observing how others react in similar but different, usually difficult, situations. To keep leading a project, keep learning. Spend roughly ten times as much time listening and reading as talking. Doing so will ensure that you are on a course of continuous learning and self-improvement. We love the phrase “You could be my teacher.” Good ideas and teaching moments can come any time and from anyone (and everyone), so every team member, or project stakeholder, can be a project manager’s teacher. Complete project managers adopt the practice of learning from anybody.

Not all project managers are ready to learn, but the truth is that every project is a learning process throughout its entire life cycle. Your growth as a project professional determines who you are. Who you are determines whom you attract, and whom you attract determines the success of your organization. If you want to grow as a complete project manager, remain teachable. Focus on project facts, analyze them, and try to learn to improve your performance.

LOVE YOUR PROJECTS AND RESPECT YOUR TEAM MEMBERS

You cannot expect anyone else to enjoy your projects if you do not enjoy your own projects. Similar to this, your actions reflect your thoughts and shape how others treat you, so if you do not treat yourself with love and respect, you are sending a signal to your stakeholders that you are not important enough, worthy enough, or deserving. In turn, customers, team members, and other project stakeholders will not treat you well. You, as a project manager, must not forget that you work with human beings. In a project I (Bucero) managed in Spain for a software development organization, I had twenty-five people on my team. My customer expected us to spend long days working on the project, and in the beginning, we finished our workdays very late. After five weeks of hard work, my team got frustrated, and team performance decreased dramatically. I was not leading by example. I did not respect myself, and I did not respect my people. That behavior stressed my team members. I looked for a solution, and I decided to end every workday at 6:00 p.m. I talked to the customer and explained two key things: first, that we were working very long hours without making good progress, and second, that people must be committed and motivated to achieve project success.

My customer did not agree with my arguments in the beginning. So I needed to spend time with him making it clear that project failure caused by lack of team member commitment would have a negative business impact. Finally, my customer agreed with me, and team performance started to improve dramatically.

An example of the importance of respecting others arose when I was working for a multinational company. A colleague from the U.K. told me that when mentoring junior project managers, he tended to do the mentees’ jobs (fishing for them instead of teaching them to fish) because he thought the work was too difficult for them as inexperienced project managers. After some time, he realized that he was making a big mistake. Instead, he began to allow people to fail, and they learned from their failures. The new approach actually made the project managers feel good because it was their responsibility to achieve their own project goals.

Some project managers sacrifice themselves for their team members, thinking that such behavior is professional and beneficial to the project, or because they believe there is a lack of resources: “There is not enough for everyone, so I will go without.” (Also, many of us were taught to put ourselves last, leading to feelings of being undeserving and unworthy.) Such self-sacrifice will eventually lead to resentment. Adopt—and attract others with—a mindset that there is abundance for everybody. It is each person’s responsibility to work toward fulfilling his or her own desires and goals. You cannot do this for another person because you cannot think and feel for anyone but yourself. This is part of respecting both yourself and others.

People are responsible for their own happiness. Do not point to another person and say, “Now you owe me, and you need to give me more.” Instead, give more to yourself. Take time off if needed. Refueling yourself will allow you to give to others. Do things that you love—that make you feel passionate, enthusiastic, and energetic, or that give you a sense of health and wellness. For example, I (Bucero) do not feel good if I do not do some physical exercise every day. I feel nervous and stressed, and that stress comes across to my people. So, every day I do some exercise to feel better.

When you tend to your happiness and make feeling good a priority, that good feeling will radiate and touch everyone close to you (like your team members). You will be enjoyable to be around, and you will be a shining example to every team member and other stakeholders. Plus, when you feel happy, you do not even have to think about giving. It comes naturally.

Unless you fill yourself up first, you have nothing to give anybody. Negative feelings attract people, situations, and circumstances that drag you down, which will affect your team and impact project results. Develop a healthy respect for yourself as a professional. Change your focus and begin to think about your strengths and the ways in which you are fortunate. Begin by focusing for a time on one of your best qualities. More positive thoughts will follow.

Everybody has a set of useful skills. Seek and you will find it. To reinforce this mindset of love and respect, especially respect for your own dreams, we quote Neal Whitten, a PMI colleague and noted speaker, trainer, consultant, and mentor:

You can rise to the top of whatever hill you choose to climb, as long as you imagine and dream you can…. If you truly want to see something remarkable, look in a mirror. The fact that you exist today means that you have overcome far worse odds than any lotto on this planet …. Leadership … is about your ability to lead despite everything happening around you. Why go through your job—and your life—being too soft, afraid to assert yourself, playing the victim, not demonstrating the courage to make things happen? Why would you want to live in others’ shadows instead of creating your own shadow? You have the wherewithal to achieve what is important to you. As Henry Ford said, “Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you are right.” Living your dream is a whole lot more exciting than just dreaming your life. (2011)

Love yourself more. Loving yourself will make you feel good and will allow you to love others. Most people want to be wanted, needed, and loved by others, to paraphrase the Elvis Presley song. In a team situation, this love translates to care and respect for others. Focus on the positive traits of the people you work with, rather than thinking, “My team members are so lazy … my customer is not committed… my sponsor is not supporting me …” Your relationships will function better if you can find attributes to appreciate in others. Even if you are struggling with a customer, executive, or team member relationship—things are not working, you are not getting along, someone is in your face—you can still turn that relationship around. For the next thirty days, write down all the things that you appreciate about that person. Think about all the reasons that you like him or her. You enjoy her sense of humor; you appreciate how supportive he is. And what you will find is that when you focus on appreciating and acknowledging the other person’s strengths, that is what you will get more of, and the problems will fade away.

In short:

• When you want to improve your relationship with a customer, team member, or executive, make sure your thoughts, words, and actions do not contradict your desires.

• Your job is yourself. You will not have anything to give anybody unless you fill yourself up first.

• Treat yourself with love and respect, and you will attract people who show you love and respect.

• When you feel bad about yourself, you block good feelings and others’ love and attract people and situations that continue to make you feel bad.

• Focus on the qualities you love about yourself.

• To make a relationship work, focus on what you appreciate about the other person and not on your complaints. Focusing on strengths elicits more of them.

Qualities of Effective Leaders

Participants in an online university course are challenged to share an essay about a leadership quality or qualities that they have admired or found particularly effective in a leader. That leader may be themselves, a manager they have worked with, a public figure, someone they have studied, or anyone else. The participants are instructed to identify the quality, describe how the leader manifested or implemented it (in other words, tell a story), and share what effect it had on them.

The intent of this activity is for participants to reflect on influential people, discuss the multitude of ways in which people lead, practice storytelling as a leadership tool, and learn from others. It highlights what participants have learned through experience and emphasizes that people have significant influence on one another. One participant, Mark, provided this stunning example of integrity and humbleness:

I met this senior manager for a general contracting company after getting hired on and knew when I came down to his office to meet him that this man was different from any other that I had met in the workplace before. His name is Scott, and he is a man of faith who demonstrated to all that we were to operate with integrity and that he would lead by example. We were working on a theme park, more specifically a themed land for a client that sets the bar for theme parks. He wanted to make sure that as team members on a $150 million project we were not going to stress out, as this was a project of a lifetime, and he wanted us to have fun while doing it.

The integrity side soon showed itself when change orders started coming in and increasing. Scott, as the senior project manager for the project, had to reel in some of his project managers as questionable pricing on change orders emerged. Scott told the managers that he would not accept this kind of practice and going forward would review the change orders that were to be submitted to the client. I am not aware if the client ever heard of this particular situation.

It was later, after this project, that I learned that the company owners operated with integrity, too. Several years later, the client awarded the same company that I worked for a $500 million project to manage other contractors as construction managers representing their interest—integrity at work. Scott’s integrity showed through not only to us as team members but also to the client. I benefited from this by seeing an example of integrity in action and to remember not only my own faith teachings, but to live a life with integrity that does not have limitations when you go to work.

Another participant, Dan, highlighted one aspect of Mark’s message:

I like the example where your manager wanted everyone to have fun working on a project instead of getting stressed out. It reminded me of a manager I used to work for who told the entire group, “I want you to have fun—whoever doesn’t have fun, make sure you come and see me!” I think that it is very important to have fun and enjoy what you are doing. It makes your day a lot shorter.

These messages resonate with us because authenticity and integrity are key ingredients for leadership effectiveness. They are the glue that holds together the pieces of the puzzle—the components of the environment necessary to achieve project success, as described in Creating an Environment for Successful Projects (Englund and Graham 2019). We also believe that leadership examples are all around, and within, us. Our lives become richer when we take the time to reflect on the blessings bestowed on us by excellent leaders—those who come into our lives and make us better people.

Of course, stories on leadership can also teach us what not to do. For example, course participant Jens wrote:

In my opinion, leaders are respected and trusted, function as role models, and have a clear vision that inspires and motivates others.

Respect can be earned in various ways, and it certainly does not require that a leader be perfect and score high on every single quality. It is important to keep in mind that all leaders have faults and missing or low-developed qualities as well. An important quality of a leader might in fact be to be aware of these issues, which actually make him or her more acceptable. A too-perfect leader could indeed set people off. A role model only serves a purpose if it seems achievable for others to develop into someone like the role model.

Leadership happens every day on small scales as well as in large historical events. Leaders and leadership skills can be found during day-to-day business, in work life, and in personal relationships such as families.

Personally, I have worked with very different leaders in terms of personalities and qualities and want to describe two of my previous bosses. I purposefully focus on the fact that both were not perfect, but actually lacked some skills. Their leadership styles were very different, too.

One of my bosses had an extreme natural talent to understand the business environment. She was very intelligent, results-oriented, led by example, and worked very hard. However, on a personal level she was difficult to work with and several colleagues did not feel as if they had a personal relationship with her. Although she inquired about the wellbeing of everyone, she just did not have the warmth/motherly tone as the other person I write about, and she was perceived as being bossy sometimes. Nevertheless, people followed her and respected her for her skills and the success she had and brought to the team. I find it important to highlight that people like her can be considered leaders despite the fact that they might not be humorous or the most likeable person. This person certainly has taught me a lot and I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked with her.

Another of my previous bosses was completely different. She cared very much for each of her colleagues, was always interested to help in situations of personal hardship, encouraged personal development, trusted people with their skills, and supported them to achieve their goals. She had a motherly aura of genuine interest and care for each employee. She was very inclusive, political, of high integrity, and had a very good talent to navigate very different situations by finding the right words in the right moment. She was very generous with praise when it was earned. On the other hand, she was not the best manager and did not necessarily make the best business decisions. However, people respected and followed her as well despite these facts.

These two very different personalities both have inspired me for very different reasons. It clearly highlights that skills and qualities differ between leaders and that each individual should try to learn the best qualities from a variety of persons and leaders to grow personally themselves. A leader comes as a package of different skills and qualities and will be a great leader if this combination of qualities will earn him or her the respect of colleagues to make them followers. Employees will follow leaders who are visionaries and see opportunities instead of problems and have an inherent drive to achieve, improve, and make things better. Respect, trust, and inspiration are the recipe for great leaders who earn the right to lead, based on different personal and leadership qualities.

Another participant, Selim, responded:

Very interesting, Jens, how you compared two former bosses, with totally opposite skill sets. I believe the one with well-developed soft skills would probably go further. It is much easier to learn about business than how not to be difficult to work with.

Jens replied:

That is true, Selim. And I agree that it is probably easier to be a good leader when you are well liked, humorous, and so on. But on the other hand, it might not be a requirement. I have to point out that she was very fair and had very high standards. You could completely rely on her. If she said she would do this or that, then she would deliver on it, which is a very good quality. Someone mentioned “to prefer a good guy over a smart guy.” She was definitely not a bad guy, i.e., a leader has to be truthful, fair, have at least some EQ, and needs to get along with people, etc. If we look at leadership qualities and put them on artificial scales from 1–10, we would probably have a minimum threshold that is required on a lot of qualities. However, the qualities that different leaders score highest values on will potentially vary significantly. Therefore, I would not single out specific qualities, as leadership personalities are made up of sets of qualities that can compensate for each other. At the end, it comes back to if you individually feel that you can respect and trust that person with that package of qualities and if the leader manages to inspire you.

Participant Val noted:

You have made some very interesting observations. I agree with you that everyone has certain leadership skills, but not everyone can possess all of these traits. The good leaders are the ones who recognize their weaknesses and strive to make those weaknesses into strengths.

I (Englund) offered an example:

Let me add that an effective strategy is to partner with people who have complementary qualities. Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard of HP fame were two such glorious examples—both very smart and technically competent where Bill was more the technical genius and Dave the business guru. Together they are more complete. I partner with other consultants in many of my engagements, even at the cost of sharing a fixed revenue, because these partners bring other qualities that make for a better experience. We learn from each other and have more fun.

Project leaders may also apply this principle in seeking team members to take on leadership tasks for which the assigned leader may be less suitable. It is another sign of good leaders to acknowledge where they are lacking, seek assistance from others, and be willing to share the glory.

Jens replied:

Great points, Randy. I am glad that you added these. I sometimes observe that project managers feel they need to be the champion of a team that is recognized as the most knowledgeable and best skilled. It might be based on a fear of replacement if somebody else does something better than the project manager. In my opinion, a true leader … manages to bring out the best in all team members and to make them work together well. I think it is a great quality to realize when it is better to step down and let another team member do what they are good at. The real skill is to see the qualities in people and to apply them to the task at hand in the best possible way to make the project a success.

Listening to Your People

Listening is such a routine project activity that few people think of developing the skill. Yet when you know how to really listen, you increase your ability to acquire and retain knowledge. Listening also helps you understand and influence team members and stakeholders. All good leaders listen to their people. To foster involvement with your team members, listen to them constantly, either in informal settings, like coffee breaks, or more formal ones, such as planned project meetings. Complete project managers, along with encouragement and support from executives and upper managers, need to develop this core skill as early as possible in their careers.

Regularly practice active listening techniques: concentrating on what is being said, employing all your senses, paying attention, nodding, making physical gestures, maintaining eye contact, mirroring, repeating back what you heard, questioning, paraphrasing, summarizing, and so on.

There are cultural differences that affect how people listen. Listening means different things to different people. The same statement can mean different things to the same person in different situations. And professionals take different approaches to listening depending on what is considered appropriate in their cultures. For instance, Spanish people look directly in the face of the person talking to them; people in some Asian countries may consider it offensive to look directly into the eyes of the person talking to them. However, it is universally true that listening is a priority. Javier, from Spain, said:

In the first stages of a project manager’s career, communication in general and listening in particular is very low priority. As the project manager grows, then communication skills and listening become critical.

Senior project and program manager extraordinaire Remco Meisner, from the Netherlands, says:

Obviously, you will need to know what customers consider important, what the project team has accomplished so far, where the flaws are—for all that you need to be able to listen well.

Courage Makes the Difference

You can lose money, you can lose allies, but if you lose your courage, you lose everything. Without courage, there can be no hope. Professionals are inspired by leaders who take initiative and who risk personal safety for the sake of a cause. Only those project managers who act boldly in times of crisis and change are willingly followed. Complete project managers need courage to manage and overcome project obstacles and issues. Great courage, strength of character, and commitment are required to survive in the project management field. It is not a place for the timid. Leaders need to summon their will if they are to mobilize the personal and organizational resources to triumph against the odds. They need boldness to communicate reality honestly to project team members.

European project managers carry a “flag of courage” as their symbol. Global multicultural projects are becoming more prevalent in Europe: project team members can come from a variety of European or other countries. Leaders running these projects need to have the courage to manage different people from different cultures, who may behave differently in project situations. J.O., a project professional from Spain, says:

The project manager must spend a lot of time understanding and listening to their team members. He or she must spend time with them. Courage consumes a lot of energy; empower your people and charge your batteries through them.

We, as project professionals, often talk about the courage of our convictions, meaning a willingness to stand up for what we believe. We need to believe in our projects, because if we do not, we will not be able to transmit positivity and passion to team members and other stakeholders. But perhaps the courage of conviction can be better understood as the willingness to risk surrendering our freedom for our beliefs. It would seem that the truest measure of commitment to common vision and values is the amount of freedom we are willing to risk.

Whatever you hope for—freedom, project success, quality, career path progress—you have to work for it. And the more hope you have, the more work you will put in to get what you want. That is because courage and actions are connected. That is what it means to surrender your freedom. If you hope more than you work, you (and your team members) are likely to be disappointed. And your credibility is likely to suffer.

But what about balance? Do complete project leaders have balance in their lives? Certainly. And balance is relative. None of us can determine if another’s life is out of balance without knowing the weights and measures in that person’s life. If a leader, for example, loads up one side of the scale with a ton of hope, the only way his or her life will be in balance is to load the other with a ton of work. Anything less would surely bring disappointment. However, if a leader has only an ounce of hope and loads the scale with a ton of work, the scale would again be out of balance. The secret is not to overload the scale on either side. When hope and work, challenge and skill are in equilibrium, that is when you experience optimal performance.

People with high hope are not blind to the realities of the present. If something is not working or if current methods are not effective, they do not ignore the problem, cross their fingers, or simply redouble their efforts. They assess the situation and find new ways to reach their goals. And if the destination begins to recede rather than appear closer, people with hope reset their goals.

Changing the strategy or aiming for another target is not defeatism. In fact, if a project leader persists in a strategy that does not work or stubbornly pursues one that is blocked, project team members can become frustrated and depressed, leading them to feel defeated rather than victorious. It is better to find a new path or decide on a different destination. Then, once that end is reached, set a new, more challenging objective.

Credibility is not always strengthened by continuing to do what you said you would do if that way is not working. Admitting that you are wrong and finding a better course of action is a far more courageous and credible path to take. Courage is also required to push back when sponsors impose unreasonable schedule, scope, or budget constraints. Without the courage up front to constructively resist and to negotiate with due diligence, project managers set themselves up for failure.

Start with Why

Simon Sinek, in his book (and TED talk) Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action says, “Everything you say and everything you do has to prove what you believe. A WHY is just a belief. That’s all it is. HOWs are the actions you take to realize that belief. And WHATs are the results of those actions” (Sinek 2011, 67). The WHY must come first. “Only when the WHY is clear and when people believe what you believe can a true loyal relationship develop.” He depicts Why in the middle of his “Golden Circle,” surrounded by How and then What in the outer circle. Ineffective leaders operate from the outside in. Sinek’s prescription for effective leaders is to operate from the inside out, starting with Why.

Sometimes we appear to do projects just for the sake of doing them. By digging deeper and asking “why,” we may influence people to rethink things.

Laws of Leadership

Here are leadership “laws” to follow, excerpted from the table of contents from John C. Maxwell’s The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership: Follow Them and People Will Follow You (2007):

1. THE LAW OF THE LID: Leadership Ability Determines a Person’s Level of Effectiveness

2. THE LAW OF INFLUENCE: The True Measure of Leadership Is Influence—Nothing More, Nothing Less

3. THE LAW OF PROCESS: Leadership Develops Daily, Not in a Day

4. THE LAW OF NAVIGATION: Anyone Can Steer the Ship, but It Takes a Leader to Chart the Course

5. THE LAW OF ADDITION: Leaders Add Value by Serving Others

6. THE LAW OF SOLID GROUND: Trust Is the Foundation of Leadership

7. THE LAW OF RESPECT: People Naturally Follow Leaders Stronger than Themselves

8. THE LAW OF INTUITION: Leaders Evaluate Everything with a Leadership Bias

9. THE LAW OF MAGNETISM: Who You Are Is Who You Attract

10. THE LAW OF CONNECTION: Leaders Touch a Heart Before They Ask for a Hand

11. THE LAW OF THE INNER CIRCLE: A Leader’s Potential Is Determined by Those Closest to Him

12. THE LAW OF EMPOWERMENT: Only Secure Leaders Give Power to Others

13. THE LAW OF THE PICTURE: People Do What People See

14. THE LAW OF BUY-IN: People Buy into the Leader, then the Vision

15. THE LAW OF VICTORY: Leaders Find a Way for the Team to Win

16. THE LAW OF THE BIG MO: Momentum Is a Leader’s Best Friend

17. THE LAW OF PRIORITIES: Leaders Understand that Activity Is Not Necessarily Accomplishment

18. THE LAW OF SACRIFICE: A Leader Must Give Up to Go Up

19. THE LAW OF TIMING: When to Lead Is as Important as What to Do and Where to Go

20. THE LAW OF EXPLOSIVE GROWTH: To Add Growth, Lead Followers—To Multiply, Lead Leaders

21. THE LAW OF LEGACY: A Leader’s Lasting Value Is Measured by Succession

Developing Relationships

All good project leadership is based on relationships. People won’t go along with you if they can’t get along with you.

The key to developing chemistry with leaders is to develop relationships with them. If you can learn to adapt to your boss’s personality while still being yourself and maintaining your integrity, you will be able to be a leader to those above you in the organizational hierarchy.

Building relationships with project team members is just as important. The job of a complete project manager, as a leader, is to connect with the people he or she is leading. In an ideal world, that is the way it should be. The reality is that some leaders do little to connect with the people they lead. As a project leader, take it upon yourself to connect not only with the people you lead, but also with the person who leads you (your manager, your project sponsor). If you want to lead up, you need to take the responsibility to connect up.

An Italian project professional noted the importance of mediation and cooperation on project teams:

The key is to mediate. Different interests can converge into a project, functional workload, and project work. The solution [to] this is always in the ability to find mediation between needs, priorities, and understanding [the] approach from both sides. If the project manager is able to find the best mediation, and the parties involved assume a proactive and cooperative approach, then the compound is stable.

A Spanish project professional said that connecting with people as people is essential to building relationships and generating enthusiasm for the work:

I believe this can be achieved [by] dealing with people as human beings, not only as employees. Being confident, respectful, sincere, creating a team spirit in the project, clarifying the common objective. These attitudes should generate enthusiasm itself.

One example of a transformational leader occurred in the U.S. Civil War during the 1860s. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain was an ordinary man of the times who became extraordinary in the context of the conflict. He had no significant military background or education but had a natural gift for soldiering and leadership. He lived up to high values and behavior, and his exceptional physical courage, capacity to withstand pain, and strong ethical and political beliefs all helped him become a Civil War hero. He was honorable and thoughtful, exceptionally curious, and read vociferously. The movie Gettysburg depicts how he turned around Union Army men who wanted to leave and not fight anymore and how he led an innovative right wheel bayonet charge at Little Round Top against the Confederates. These actions saved the day for ultimate victory. After the war he went on to become a state governor and college president.

An example of servant leadership was depicted in the TV series Galavant. The knight Galavant and King Richard visited a village and discovered the king’s castle had been torn down. He attempted to command it be rebuilt but met with this response: “We tore it down to make room for shops. When you left us, we didn’t hear anything for a long time. While you were away, we realized a king is only a king if the people say he is. And if we don’t, well, he’s just a man with a metal hat who’s only in charge because his father wore a metal hat before him. So, we came together and asked ourselves what if there was a different way of doing things, a better way.”

Professional Development

A report on leadership ups and downs notes that 56 percent of global executives say their company isn’t ready to meet leadership needs; 89 percent say improving organizational leadership is an important priority this year. But one in five companies have no leadership program at all (Deloitte 2016).

Complete project managers need to take responsibility, self-manage, and continuously develop their careers. We draw upon Jim De Piante’s brilliant “compost pile” analogy as a model for professional development, presented at a PMI Global Congress (2009). Here, we summarize key points of his talk:

Historically, the ladder has stood as a metaphor for career success. Why? Because ladders let you climb, one rung at a time, to the heights you aspire to achieve. But ladders have problems. They’re unstable. They’re dangerous. There’s only room for one person at a time on a ladder. And of course, ladders also have long-standing associations with bad luck. It’s time for a new model. The compost pile offers a much more robust model, a model adapted to changing times and to the new millennium. It is a model of growth, of sharing, of happiness. It is a way of understanding career success in organic terms—where the accumulation of your life’s (decomposed) experiences provides a broad and fertile base on which to cultivate and accumulate new and ever more valuable experiences. The pile grows ever fuller, without losing stability. It is about career growth, death, decay, and rebirth. Whatever comes your way in life, just put it on the pile and let it ripen. Career ladders are out. Compost piles are in.

Philosophers and pundits throughout the ages have unanimously concluded that happiness is not to be found in getting what we want; rather, it is to be found in wanting what we get. We seem to be slow to understand this important message, however, and often seek happiness, especially in our careers, in terms of chasing, climbing, having, getting. The ladder has served for several generations as a model of career success. But it is a very limiting model. It defines success in terms of climbing higher. This is usually to be understood as higher in the organizational hierarchy. Such language usually serves as a metaphor for higher compensation—that is, success is equated with more money.

When I first came to IBM, I sought the advice of wiser and more experienced people. I was intrigued to learn that IBM proposed not one, but rather, dual career ladders (technical and managerial), and was informed that a person could readily and safely move between the two. I found this model dissatisfying and sought a model that would suit my temperament more closely.

Being generally a happy individual, and looking for a way to synthesize that happiness with a more satisfying model, I proposed the compost pile as a model of accumulation and growth. I found it very useful and robust and so presented it to various colleagues who readily embraced it and enhanced it. The model has withstood fairly rigorous application, and I believe the time has come to give it wider exposure.

Metaphysically speaking, we are the sum total of what we learn, what we experience, what we create. We increase in knowledge and in wisdom, taking what is given to us by the sun and giving it back to the world that is illumined and warmed, also by the sun. In the end, we can do little more than pass on the wisdom that we have accumulated. Then we also become the soil, quite literally uniting the humus of ourselves to the collective Wisdom. With a model such as this, progress is judged to be in what we will have become, and not in how high we will have climbed. There is purpose and value in all of life’s experiences. We will interpret and evaluate our careers and our lives according to a model, and we are free to choose which model we will use. This is a model that we can use to synthesize our happiness. We might say that this is a model by which we might use the light of the sun to photosynthesize our happiness.

Jim’s analogy fits with our reference to molecular structure as an organic depiction of the complete project manager. Through natural, ongoing processes, scraps turn into beautiful humus … but not without some stinky in-between steps. By adding waste products such as manure (which we can think of as a metaphor for learning from bad experiences) to the compost, the process of creating rich soil is accelerated. The output, when the soil is added back into nature’s garden, is a bountiful harvest. Similarly, we become better people, managers, and leaders by continually expanding and growing our skills and using lessons learned.

Put in the effort for continuous, lifelong learning and professional development. Use every interaction as learning and/or teaching moments.

Building High-Performance Teams—a Leadership Imperative

New research reveals surprising truths about why some work groups thrive and others falter. Google—known as a zealot for studying how workers can transform productivity—became focused on building the perfect team. The tech giant spent untold millions of dollars measuring nearly every aspect of its employees’ lives. The company’s top executives long believed that building the best teams meant combining the best people. Understanding and influencing group norms became the keys to improving their teams. Google’s data indicated that psychological safety, more than anything else, was critical to making a team work. They defined psychological safety as a “shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking …, a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up…. It describes a group culture and team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.”

Here is a summary of leadership findings to create psychological safety, faster, better, and productively, that are relevant to complete project managers (Duhigg 2016):

• Encourage conversational turn-taking and social sensitivity

• Discuss norms for group interactions—a common platform and operating language

• Develop a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking

• Build a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up

• Cultivate a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves

• Create psychological safety, more than anything else, as critical to making a team more complete or near perfect.

A Code of Ethics for Project Leaders

Most businesses today are applying or working on reviewing the way in which they manage ethics. This topic has taken on increased impetus on all fronts, from personal to organizational to governmental.

Here are worldwide descriptions for ethics:

• From ancient Greek ethos (character)

• A set of principles of right conduct

• A theory or a system of moral values

• The study of the general nature of morals and the specific moral choices to be made by a person

• The rules of standards governing the conduct of a person or the members of a profession

Many organizations are elaborating a code of ethics. A code of ethics needs to take into account the following:

• Respect. We listen to other’s points of view, seeking to understand them.

• Responsibility. We do what we say we will do.

• Honesty. We honestly seek to understand the truth.

• Fairness. We demonstrate transparency in our decision-making process.

A MATTER OF CHOICE

We believe that we can advance our profession, both individually and collectively, by embracing a code of ethics and professional conduct as individuals but also as leaders.

• As individuals: We believe that this code will assist us in making wise decisions, particularly when faced with difficult situations where we may be asked to compromise our integrity or our values.

• As leaders: We hope that demonstrating a code of ethics and professional conduct will serve as a catalyst for others to study, deliberate, and write about ethics and values.

LEADERSHIP AND ETHICS

Kouzes and Posner (2017) say: “It’s clear that if people anywhere are to willingly follow someone—whether it’s into battle or the boardroom, in the front office or on the production floor—they first want to be sure that the individual is worthy of their trust.”

Every leader needs to be ethical based on these principles:

• Trust. The ethical leader inspires, and is a beneficiary of, trust throughout the organization and the environment.

• Authority. The ethical leader has the power to ask questions, make decisions, and act, but also recognizes that all those involved and affected must have the authority to contribute what they have toward shared purposes.

• Purpose. The ethical leader inquires, reasons, and acts with organization purposes firmly in mind.

• Knowledge. The ethical leader has the knowledge to inquire, judge, and act prudently.

We believe that ethical leadership is the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision making.

ETHICS VERSUS PROFESSIONALISM

Students in an online university graduate course prompted several questions and comments on what is ethical/unethical versus professional/unprofessional behavior. So I (Englund) invited noted author and ethics professor Dr. David Gill to comment. Here is his reply:

Language meaning and usage evolve over time, and it is fairly common for people to describe something as “professional” or “unprofessional” in the sense of “appropriate” or “inappropriate” to the particular business context. Thus, we might think about our dress, communication style, office decoration and atmosphere as professional (or not). It is not too different from good manners or respecting the customs of a given context.

Ethical/unethical (and their linguistic cousins moral/immoral) distinctions are about right and wrong, something a little different than appropriate/inappropriate or offensive/inoffensive. But the question then becomes “Who gets to decide what is right and wrong?” All human beings carry around a kind of internal moral compass, a set of convictions, a conscience that guides them in making these judgments. We should certainly listen respectfully to each other’s ethical convictions but even in the best of circumstances we will always have some disagreement. Different religions have somewhat varying ethical standards—and different nations have different standards of conduct (represented in their laws and regulations).

This rich but challenging diversity is why many companies and most professional organizations (doctors, nurses, accountants, engineers, marketing, law, etc.) develop codes of ethics or standards of conduct to serve as their ground rules and standards for conduct during our hours working for them. These codes and standards can really help if they are done well.

Historical note on profession: The four classic, traditional characteristics of a profession (setting it apart from mere commerce, it was thought) were (1) a high level of education and expertise, (2) accountability to a community of peer professionals, (3) commitment to a service mission, not just financial profit, and (4) voluntary submission to a code of ethics which demanded high standards of conduct, even if the law permitted something less. So, in bygone centuries to say something was “unprofessional” might have implied bad ethics.

Historical note on ethics: What seems to be the common characteristic of all ethics is not just that common standards of behavior are being violated, but, much deeper, that somebody might be harmed. At bottom, what makes something unethical is that somebody might be irresponsibly, seriously harmed (physically, financially, reputationally, etc.). If they are or might be offended, it’s about etiquette and manners. If they could actually be harmed, it’s about ethics.

STEPS TOWARD ETHICAL DECISION MAKING

Michael O’Brochta and his colleagues (2012) describe the strong connection between ethical decision making and project leadership success, depict the role that an ethical decision-making model can play, and present the five-step PMI Ethical Decision-Making Framework (EDMF) created by the Ethics Member Advisory Group (Ethics MAG) and released PMI-wide. They state:

It is not uncommon for ethical challenges to arise that cannot be easily addressed with a simple or quick interpretation of an ethics code. Complex, time-consuming, and often stressful dilemmas are a frequent part of the leader’s decision-making portfolio; careful resolutions take time and effort. Leading-edge organizations have condensed the critical elements of their codes into a sequenced “ethical decision-making model” or “framework” that guides the decision maker through a series of steps that direct him or her to making the most appropriate choice possible. The practical ethical decision-making framework is carefully tied to the values and codes of the organization, uses language familiar to members of the organization, and can be illustrated with examples of situations commonly encountered by the organization’s members.

Although no code or EDMF can resolve definitively most specific ethical dilemmas, a good code and EDMF can help to clarify the situation, eliminate poor choices, and illuminate better possibilities. No tool builds a cathedral, nor does it repair an automobile, or clear a blocked artery. The tool, in this case a code coupled with an EDMF, is only as useful as the skill of the person wielding it. Leaders need to develop ethical decision-making skills; codes and decision-making frameworks help leaders do that.

They offer this case as an example:

Andy works in a temporary job as a project manager in a small training and consulting company that is run by his boss, Sarah. Since business is growing fast, due in part to Sarah’s effective use of potential client lists, Andy is increasingly hopeful that his job will become permanent.

Andy and Sarah each has a Project Management Professional (PMP)® credential, and they serve as volunteers at the local Project Management Institute chapter. Sarah’s volunteer role at the chapter includes responsibility for membership, where she has used her communication and marketing skills to help increase the chapter membership significantly.