10

Change Management Skills

All meaningful and lasting change starts first in your imagination and then works its way out. Imagination is more important than knowledge.

—ALBERT EINSTEIN

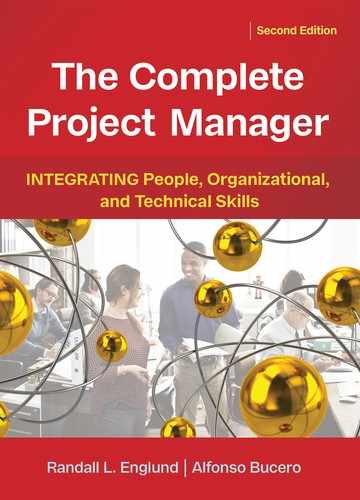

By definition, projects create change, and all attempts to improve project success rates involve change. Integrating change management skills is requisite to achieving complete project manager status. Since the environment for today’s projects involves so much chaos, as identified in Chapter 9, complete project managers would be well served by becoming skilled at managing the inevitable changes that arise from the chaos.

In this chapter, we share thoughts about managing change, describe the three-part change management process, and discuss the need to be adaptable. We use an example of implementing a project office for organizational change to illustrate the phases of change management and a banking case study to explain approaches to implementing change. We compare and contrast change control with change management. We also share examples from other project managers about their experiences in managing change.

Managing Change

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Palos in southern Spain in search of a western route to Asia. He was convinced that the world was round, although nearly everyone else in Europe believed that it was flat. Most people believed that a ship sailing due west would fall off the edge of the earth.

Columbus did not find the route he sought, but he did confirm his suspicions that the earth was a sphere. After months of exploration and the loss of one ship, he returned to Palos on March 15, 1493, as a hero. In a matter of months, Europeans’ perspective on the shape of the earth began to change drastically—but not everyone was ready to change their minds about the earth.

Everyone resists change. For many years, we thought that project leaders liked change but everyone else did not. As visionary project leaders, we always felt that we were drawing reluctant followers into the future. But we finally realized, after extensive studying and reflection on the idea, that project leaders do not like change any more than followers do unless, of course, it is their idea.

REASONS FOR CHANGE AND TYPICAL RESULTS OF CHANGE EFFORTS

These environmental factors consistently affect most industries and spur most organizations to consider new responses:

• External factors

— Obsolete products

— Customer requirements

— Competitive offerings

— Time compression

• Internal factors

— No consistent methodology across organization

— Lack of skill

— Training is not producing results

— Inadequate support

— Projects do not meet scope, schedules, and budgets

These are typical, haphazard responses, but they are not usually effective:

• Actions

— Exploit new technology

— Institute policies and procedures

— Search for new customers

— Solve new problems

— Focus on solutions, not just products

• Reactions

— Initiate projects … more projects … and even more projects

— Delays … failures … more projects … hastily conceived project office

• Results

— 80 percent or so of work is attempted through projects

— Organization fails to execute its strategy and becomes an ineffective project-based organization

— Something needs to change

Always bear in mind the words of caution expressed centuries ago by Niccolò Machiavelli: “There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.”

EXPECTING RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

Making a change is very difficult. It is widely accepted that there is a degree of pain that underlies even the happiest of lives. This suffering is self-inflicted. Its root cause is ignorance reinforced by attachment, expressed as grasping onto things we want but cannot have and pushing away things we do not want but cannot avoid.

For instance, I (Bucero) am a family lover and want to be with my family most of the time. However, my professional life as a project manager and as a consultant has changed over the last few years. Business and the economy in Spain went down, and I had to travel more frequently than usual in order to get business in other countries and make a living. That situation provoked suffering. I felt that I was always working and far away from my family. But the situation was as it was, so I had to be flexible. I adapted to my new way of professional life. I remember my father’s words, “In your professional life, the only inflexible things are stones,” every time I go through changes in the projects I manage. Complete project managers need to be flexible when change is needed.

MOTIVATION TO CHANGE

Change is always a constant, and we sometimes have a choice to make or help it happen. Motivators for change are suffering, avoidance, and the achievement of pleasure. Of course, these are linked. The avoidance and elimination of pain is pleasurable. R&D and new commercial-product development projects can represent pleasure acquisition. Most performance improvement projects represent suffering avoidance. Both face resistance to change.

Resistance seems to grow exponentially with the degree to which the change threatens the structures we are used to. But we do not want to wait for our suffering to become so bad that it overcomes our resistance to change. We want to be able to proactively change the things we have control over to improve our performance.

Resistance is both positive and negative. Often fear has a rational quality, and if it is managed well, it provides a solid base for managing risk and making effective decisions. By assessing the negative possibilities, we can find means for avoiding them or moderating their effect. It is by examining resistance that we make decisions regarding the best way to make a desired change.

Remember, fear is natural. Our courage is defined by the way we address our fears. Attachment is natural; our ability to be proactive is defined by the degree to which we address our attachment. If we can be mindfully aware of the underlying feelings that create our resistance, we can respond rather than react. We can feel the fear or desire and note it before it turns into a thought and action stream (that sequence of mental, verbal and physical events that are behind our behavior) that drives us to react. Instead of immediately giving in to our fears and desires, we can analyze, plan, and act.

Resistance to the implementation of PM methodologies exists at many levels in organizations. Most serious is resistance from executives and senior managers. They are the ones who decide whether to address the underlying problems, ignore them, or push some Band-Aid solution in the unfounded hope that it will work. Once decision makers have bought into an organizational change at any level, the resistance from others can be managed with relative ease, assuming it is recognized and included in the project plan.

How to manage this resistance? Managing change begins with the recognition that a project will affect the way people work, their relationships, security, authority, power, or any other tangible or intangible element they hold dear. With this recognition comes the likelihood of resistance.

The next element is planning. Include in the project plan a strategy for avoiding and moderating the impact of resistance. The strategy is translated into activities required to inform people, at the right time and in the right way, of what is going on, how it may affect them, and what roles they are to play. It also includes staffing for support activities that provide a smooth transition to the new process, including training, coaching, and general hand-holding. Activities to manage the change and resistance to it are performed throughout each project’s life, not just at the end.

If resistance is found at decisionmaker levels, more subtle management is required. There is likely to be no project or the wrong project if executive and senior management resistance is not addressed during origination of the project (the time when the project is a gleam in the eye of its champions) and during project initiation and high-level planning (when the project’s strategic approach is being defined). Here, the project champion(s) needs to courageously and skillfully build a case that cuts through irrational resistance while realistically addressing the potential for failure.

Use the Change Resistance Tool in our online Toolkit to evaluate the resistance to change.

CHANGE READINESS

The term “change readiness” refers to the degree to which a person or organization is prepared to take a positive role in making change. The role may be that of a change agent or a change recipient. While readiness can be cultivated through a communication and education process, there are times when all one can do is patiently back off and wait for another opportunity when readiness emerges. Readiness for change may be the result of reaching a point of insufferability or emerging from the ignorance that underlies our grasping and avoiding reflexes.

Emerging from ignorance generally happens through an evolutionary process that includes education and changes in the general acceptance of new ideas. For example, in project management improvement, general awareness and acceptance of a set of best practices within a PM discipline is a prerequisite for many organizations to take action. That action requires a change to the way portfolios and cross-project resources are managed as a means for addressing project performance problems. Prior attempts made to implement formal project and portfolio management may have been met with strong resistance and often failed.

Resistance to change is a fact of life. People often prefer an unpleasant but known situation to one that promises relief from suffering at the cost of changing the status quo. This resistance is based on fear of the unknown, grasping onto things such as perceived security and power, and attempting to avoid the unavoidable. The ultimate root cause of resistance is ignorance of the inevitability of change and of the ability to, at least to some degree, proactively direct change. A positive effect of resistance, however, is that it can stimulate an effective risk management process. We can affirm that change management needs to be part of any project plan that involves organizational change.

CHANGE ASSESSMENT TOOL

We suggest assessing readiness for a change using a tool. The purpose of the Change Assessment Tool in our online Toolkit is to increase organizational awareness regarding any planned change. It provides a high-level risk analysis of potential areas affected, serving as a first-level assessment of the situation. The risk is assessed regarding eight critical success factors of the foundation for the change.

Use this tool with all stakeholder groups. It is useful at different levels and with several functional groups. This tool serves to contrast opinions and can be used as a test for issues that might arise. The tool assesses:

• Motivation to change

• Change commitment

• Change shared vision

• Culture fits the change

• Organizational alignment

• Communication

• Transition planning

• Skills

The Change Management Process in Three Parts

PART ONE

As change comes in many forms, let us take a specific example. Imagine that our goal is to implement a project office as a vehicle for organizational change, especially a change toward a more projectized organization. Creating a project office may be the “in” thing to do, but it is also fraught with perils. The first step, then, is to discover the processes necessary to lead organizational change and create the conditions that will enable change. This time is akin to the preparation of a project plan.

Some will say the planning is a waste of time. Some may press for quick results and eschew the entire planning idea. Others may agitate to quicken the process and get to action sooner. But project and program managers know better. They know that planning is essential. For those who insist on skipping this first phase and taking a shortcut, here is a cautionary tale.

In the spring of 1846, a group of immigrants set out from Illinois to make the 2,000-mile journey to California. They planned to use the well-known Oregon Trail to get there. One part of this group, the Donner party, was determined to reach California quickly and so decided to take a shortcut. They traveled with a larger group until reaching the Little Sandy River. At this point, the larger party turned north, taking the longer route up through Oregon and then to California. The Donner party headed south, taking an untried route known as Hastings Cutoff. Since no one, including Hastings himself, had ever tried this cutoff, they had little idea of what to expect. Their first barrier was the great Salt Lake Desert, where they encountered conditions they had never imagined: searing heat by day and frigid winds at night. They faced an even more formidable barrier when they reached the Sierra mountains. Because the “shortcut” had delayed their progress, it was winter, the worst ever recorded in the Sierra, and a severe winter storm forced the party to camp in makeshift cabins or tents just to the east of the pass which today bears their name. The majority of these unfortunates spent a starving, frozen winter trapped in the mountains. People resorted to cannibalism. Many of the party died, and those who survived reached California long after the other members of the original group from Illinois.

The Donner party:

• Had little understanding of how difficult the journey would be

• Was inexperienced and traveling without a guide

• Took the gamble of their lives

• Followed a route that was vague, untested, unexplored, and unknown

• Had an impractical plan

• Found themselves on a road to disaster

A first conclusion for the project office team is that many have gone before you on a journey of organizational change. Their collective experience forms the equivalent of the Oregon Trail, a process showing a known way to reach the desired goal. Although this path may seem long, ignore it at your own peril. Second, although the Oregon Trail was well known and well traveled, it was not necessarily easy. There were many difficulties along that trail too, and no doubt some travelers died. So, taking the Oregon Trail is no guarantee of success, but it seems to greatly increase the chances. Third, taking a shortcut leads into unknown territory, like the Salt Lake Desert. It may look all right on the map, but the map is not the territory. Shortcuts may lead to missed requirements and bad outcomes.

When asked about how one would like to be perceived by others, project manager Dennis H. applied the above cautionary tale. “After the completion of a project, I would hope that the stakeholders would look forward to working with me again. As a project leader, I would like to have the reputation as the wagon master who led the settlers to Oregon, as opposed to the wagon master who led the Donner party.”

So, read the books and articles about creating a project office (or whatever your objective), seek out mentors, get a good map, and follow the process. Be clear about the problems, who wields the power, where you are going, and how you will get there. Assess the environment prior to proposing a project office, identifying strengths and weaknesses that suggest and support or will veto or thwart the approach. As the goal is to optimize the performance of projects across the enterprise, determine core values that form the foundation for all work in the organization. Identify necessary players in the process and a leadership approach. The best advice for project office planners considering a shortcut was given by Virginia Reed, a Donner party survivor, advising, “Remember, never take no cutoffs, and hurry along as fast as you can.”

PART TWO

Part One of a change management process creates conditions that allow change to happen. In Part Two, you change the emphasis from planning to doing. Now is the time to make contact with those people in the organization who must actually carry out the planned changes. A military dictum asserts that “no plan ever survives contact with the enemy.” The members of the organization are not the “enemy” in the classic sense, but they can be expected to respond in ways that are perhaps not expected, not planned, or not even imagined.

Here are some suggestions:

• Be flexible. A plan is a metaphor, not a law. Treat the organizational change plan as a guide to behavior and not as an imperative. This is the essential idea in another military dictum that “a plan is nothing, but planning is everything.”

• Beware. Things may go easily at first. Change agent teams often report that initial efforts are met with easy acceptance. This often instills a false sense of security, an idea that things will continue without much resistance. However, what it usually means is that the opposition has been caught off guard. This is an easy time to prevail—until the opposition gets organized.

• Be alert. Unforeseen opposition could arise at any moment. The path may seem clear, but there are lions, tigers, and bears hiding in the bushes. Develop a political plan and implement steps to approach the jungle proactively.

• Be ready to improvise and make changes in the plan to adapt it to reality. There are three choices for every step in the plan. First, leave or exit a step if it does not seem to be working. The second choice is to modify that step, making changes based on the reality encountered. The third choice is to push on if the step seems to be working as planned.

Find a small project that is in trouble, show how standard project management methods can help the project, generate a win from this project, and then use that win to develop legitimacy and move on to larger projects. The project office team may suddenly find themselves involved in a huge, highly visible, bet-the-company type project. This case requires a radically different approach, an obvious change in plan. Some suggest that developing broad-based actions toward a project office should begin with project manager training and then develop its expertise so that the office can eventually help in project portfolio management. However, it may be that assisting in portfolio management is the first task that the project office members are requested to do. A change in plan would then be needed.

Contact with the organization often results in situations that seem chaotic. There is no clear-cut, organized approach to responding to chaotic situations. Consult your map and push on.

PART THREE

Part One is creating the conditions for change; Part Two is making the change. We are now ready to enter the final phase of the journey, the toughest part: making change stick. If the change agent team has made it this far, some amount of time has elapsed. The project office has no doubt changed many times, perhaps moving from a project control office, then to a project management center of excellence, and perhaps on to a strategic project office.

The organization itself has probably also changed many times, perhaps becoming more centralized, and moving to decentralized, then maybe back to centralized again. A chief project officer may have been appointed, with power equal to the chief operating officer, thereby defining a matrix diamond form of organization structure. The CEO may have changed, perhaps several times. Several management fads have come and gone as people have moved from zero-based budgeting, been through major “Neutron Jack”–style downsizing, tried reengineering and maybe even a balanced approach.

If the project office team has existed through all that change and has implemented the structures and processes suggested so far, they may begin to feel that these changes have become permanent, that they have made a lasting change in the organization. Would that that were true.

Experience indicates a far different scenario. Think of the organization as being like a large rubber band, stretched between two hands. Adopting all project management changes has caused people in the organization to twist, turn, and stretch. As long as the tension is maintained, the organization remains in the stretched position. The moment the tension is released—one hand releases the rubber band—the organization snaps back into its original position (see Figure 10-1).

Most large organizational change processes become identified with one person or one group of people. As long as those people remain in power in the organization, massive efforts are expended to help power the change. Meetings are held, conferences are attended, committees are formed, and announcements are made in the annual report. All this is done as organizational members strive to show that they support the change. However, on the day that the lead person leaves the organization, or perhaps the change agent team falls from power, everything stops. Meetings on the change process are no longer held. Committees are disbanded; everyone suddenly has higher priorities. The announcement in the annual report is forgotten. The visitor coming to the organization the day after the lead person has left would have difficulty finding any trace of activity indicating that the change had ever been considered. The organization snaps back that fast.

Figure 10-1: Rubber Band Stretch

The problem of maintaining the change after the change initiators leave means looking forward to a changed state and starting to build the framework to achieve it. Apply leadership, learning, means, and motivation—not two or three of the factors but all four—to the components of organizational maturity identified in Chapter 5 in Creating an Environment for Successful Projects (Englund and Graham 2019). The goal is to reach the “tipping point” (Gladwell 2002), where key people, processes, and the environment align to support the changed state. The key to success is to maintain the pressure for so long that there is no one left in the organization who remembers doing things any other way. When that is the case, there is no former situation for the organization to snap back into, and so the new processes become organizational reality. Good luck.

Change Control versus Change Management

The term “change control” generally refers to the actual administration of changes to the project and ensuring that any changes are approved, incorporated, documented, and so on. Change management involves paying attention to the broader issues, mainly organizational and human resource–related, that impact not only projects going through change but also how people in general are being affected by any changes. This includes dealing with and overcoming resistance to change from individuals who may feel threatened by change and to reactions within the organization because its current structure is not prepared to handle change. Change management does not just happen after a change is approved through a change control process but also occurs beforehand, in establishing if, why, how, and when any changes should be managed.

Change control is the detailed process of managing changes to any of the triple constraints of the project. Change management is the process of managing people to adopt, adapt, and apply a change. High-performing project leaders need to be adept at both. Whether or not we get confused by the terms, it is important to think through these issues when implementing all changes at individual, team, project, and organization levels.

The change management steps—create the conditions for change, make the change, and make the change stick—apply to any initiative. For example, if an organization were to introduce a more detailed process for controlling changes to projects, that would require following a change management process to get a change control process implemented. Likewise, if you want to be an evangelist for getting more project management processes implemented in your organization, you need to take a change management approach.

Project manager Christen G. offers this perspective:

The Project Management Institute’s PMBOK Guide defines change control as “identifying, documenting, approving or rejecting, and controlling changes to the project baseline.” It also describes it as “determining corrective or preventative actions or re-planning and following up on action plans to determine if the actions taken resolved the performance issue.” From this, it can be seen that change control refers more to determining what change is needed and what should be rejected. This is in contrast to change management, which deals more with change that has been approved to happen and implementing it.

Lessons from Creating the Project Office (Englund, Graham, and Dinsmore 2003) talk about the stages of change management: lead organizational change, understand sense of urgency, build guiding coalition, develop vision and strategy, harness internal support; manage complexity, implement, keep moving, staff and operate; look forward and tell the tale. These terms deal with the same core objectives—making sure change that is good for the organizations and/or projects’ goals is authorized and leading the organization through the change to ensure a positive outcome.

The lessons also talk about creating an environment for change. I see this as more change within an organization and not as much about a change request on a given project that only affects the outcome of the project. Change is necessary for companies to grow and become stronger, more profitable companies, and it is part of having a strong change management system in place to allow this to happen. Project managers are active in both activities yet in different capacities. Change control is more of an adviser role to the process of performing integrated change control. Change management is an adviser role to the organization and the behaviors of the team members or employees affected by the change.

In my experience, there are two distinct types of change—change to the scope/time/cost of a project and change to a company’s policies or purpose/vision. At my agency, there are always changes on a project—our clients change scope frequently and we are often scrambling to change scope without changing the cost/time portions of the project—from which I’d say our change control procedures could use some improvement. Whereas regarding change management, we are at the tail end of a change to company direction started a couple years ago. There has been a shift in advertising from more traditional forms (TV and print) to digital forms (online banners and social channels). Our agency has made it a mission to change to a more digital-focused firm. This change has been met with resistance from some employees who were comfortable in their known forums and scared of learning new things. So one of the biggest factors in managing this change has been the leadership team. In looking at the change phases, they definitely correlate to what we have gone through. What I’ve found is that project managers have been able to cross-train with less resistance than some of the other departments, and we are seen as role models in reacting to the change.

Case Study

If a company, in this case a banking company, is to remain among the leaders in the market, it depends on having the capacity to change behaviors, skills, structures, and processes. This study describes a process of leading change that was necessary at Caja Granada, a Spanish banking company, in order to reduce resistance to change and to take advantage of favorable existing conditions. Every change is traumatic by itself; this project required effort from everybody in the organization. Some individuals responded well, while many others resisted efforts to change their behavior. Hewlett-Packard Consulting in Madrid was chosen as the main contractor. As the project manager, I (Bucero) took on the task, with the team, of making things happen through project management skills and processes. The entire organization needed to change to accomplish the project objectives. Success was possible because of people’s willingness to learn, ability to motivate the project team, and refusal to give up in the face of extremely difficult situations.

PROJECT BACKGROUND AND CUSTOMER OBJECTIVES

The customer was a leading banking company in the south of Spain. For ten years, it had been a very large user of UNISYS systems and solutions and had experienced stability and good business results throughout that period. Systems and methods that remained static for many years and did not allow for rapid and substantial change now came under tremendous competitive pressure.

The customer had a very clear idea that users were happy using the old system. But a change was needed as quickly as possible in order to survive among banking competitors. The proximity of Y2K forced all financial entities to be prepared, meaning that they had to update or create processes, train people, and upgrade or change technology.

The project, Red Castle, started in September. Red Castle was an information systems strategic project. It consisted of functional and technological innovations that answered market and environment needs by implementing a hardware and software platform, developing a customized software package, and managing the change.

Looking at all the changes required, my challenge became to start work with a new customer and understand all project stakeholders and their behaviors.

The client’s business objectives were:

• Performance improvement. Some processes caused hours of delay while offices demanded more transactions.

• Growth. The bank needed to increase the number of branches in its organization without any loss of performance.

• New technologies. They needed more value-added competitive offerings; changing their platform and software was a must.

CHALLENGES

One of the most complicated tasks was to convince upper managers of the bank about the necessity of project planning. At the beginning, the customer was very involved. After the first month, the customer asked for tangible results. I explained that planning is absolutely necessary for project success. I borrowed equipment and dedicated one team member to the startup of one machine in order to demonstrate to the customer how HP was able to operate in his platform. That diminished customer pressure for a while.

Managing challenges throughout the project was a part of managing the change and is a project manager’s responsibility. Clear communication and intimacy with bank managers were critical success factors. I tested the link between the Red Castle project and the bank strategy—that link proved very helpful for us throughout the project. At my prodding, upper management assigned the highest priority to this project.

THE PROCESS

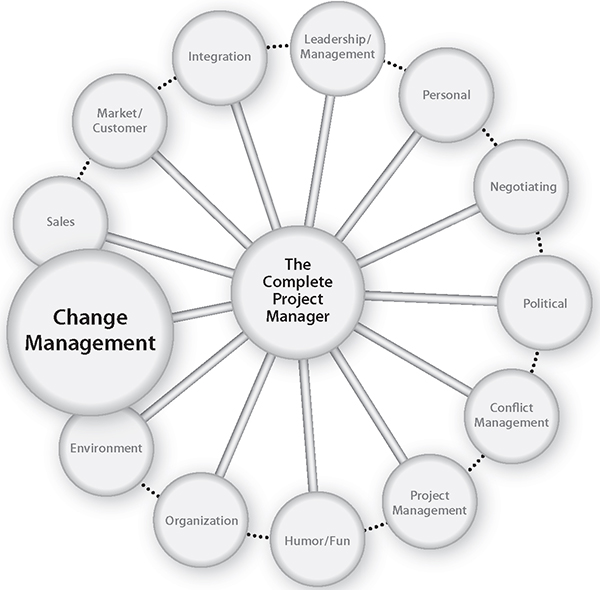

Hewlett-Packard’s corporate Project Management Initiative (a form of project office) had summarized a process for leading change. I applied the process (see Figure 10-2) in order to get support and minimize impact on the customer organization.

Figure 10-2: Steps in a Change Process

IDENTIFYING PROJECT KEY PLAYERS

It took more than two months to analyze all critical players in the customer organization. Starting the first month, I organized periodic meetings in order to get people involved and inform them of project status. One of my daily tasks was to be available for everybody in order to facilitate information flow and communication among team members.

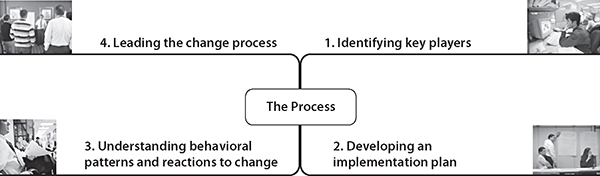

One critical success factor was getting sponsors on board who had the authority to commit resources and would support the project manager. The customer considered this project strategic and totally linked with business objectives. The HP Initiative model establishes four categories of key players: advocates, sponsors, agents, and targets (see Figure 10-3). I was the agent of the change, but honestly, at the beginning I felt like an advocate. I had to be proactive and self-confident and had to get customer confidence to create an open line of communication.

DEVELOPING THE IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

The first thing we did was identify events that would guarantee the change and help everyone understand the value of the change. We involved all team leaders early in the planning phase, discussing different options to be implemented. This was not difficult because every team leader was responsible for a different functional area and knew the old system very well.

We analyzed the gap between the old system and applications and the new one. Also, the plan needed to take into account changes to processes, systems, people, and the organization. Then we developed a plan for implementing the change, considering the possible impacts and contingencies in terms of process, people, and technology.

We needed to ask for support from bank upper management in order to facilitate the change. I persuaded them by sharing facts and rationale to help them conclude that the plan for change was effective. When the plan was finished, we asked for approval for the implementation plan from the sponsor, and I got consensus from the steering committee and from other stakeholders in the organization.

Figure 10-3: Roles in Change Management

UNDERSTANDING BEHAVIORAL PATTERNS AND REACTIONS TO CHANGE

As usual in this type of project, we detected inhibitors to the change throughout the project life cycle. I needed to have personal meetings with all branch directors to clarify project goals and objectives and convince them of the major benefits of the project for them and for their business.

The bank imposed the change, but we explained group by group all the reasons and justifications for that change. The result was that resistance diminished because we established good mechanisms for communication.

The customer situation was stable in terms of process, people, and technology, and the upper managers of the bank knew how to motivate and compensate people in order to ask for extra effort. They knew they could not ask for extra effort without compensation. Then they defined metrics and personal objectives for every team leader in the project.

One success factor in this process was to recognize different behavioral patterns and to allow enough time to work with everybody in the organization.

LEADING THE CHANGE PROCESS

• Lead. We defined eight functional groups and specific goals for individuals. We empowered those team leaders to participate in most decisions. I usually needed upper management and customer support for getting these things done, but I could also influence others without a lot of power.

• Test. We invited people to express their reactions to the changes. This feedback was very valuable in learning from errors and making improvements.

• Recognition. We established metrics that allowed room for improvement and recognized the efforts and achievement of the team and team leaders.

• Follow-up. Every project is alive and needs to be monitored. In this case the follow-up consisted of weekly brief reviews with team leaders, analyzing the results and learning from our experiences.

THE TEAM

The team consisted of functional team leaders who owned the whole project life cycle for every functional area in the bank. Every functional leader was responsible for talking and meeting with end users, leading his or her software development team, and managing all tests. HP consultants trained these leaders to be prepared for managing and motivating their teams, and the leaders were supported by an HP project manager.

Steering committee members also participated not only in sponsorship tasks but in all communication and dissemination tasks that contribute to project success. They talked to and supported people, boosting morale and recognizing their efforts in public ways.

TOOLS USED

• Teamwork exercises, using real meetings to put ideas into practice

• Definitions of roles and responsibilities that were then published in planning documents

• Change agent training

• Daily communication among team members

• Asking for feedback from every team leader

• Communication and respect among team members

RESULTS

Projects frequently fail not because of technical reasons, but because people in the organization refuse the change. The critical success factor to implementing systems is the way in which human and organizational factors are planned; technology is a second priority. This message was not understood by the whole management team at the beginning. It took six months of work to convince everybody.

From the customer’s perspective, we can measure results according to a number of parameters, but when we talk about the management of change, we talk about process, people, and technology that are the enablers of a change.

• Process. Processes need to be defined, modified, and used by people. Implementing new processes was one of the most difficult parts of this project, but people involved in that area were proud because they had the opportunity to contribute to project success and then be employees of a successful bank. By reviewing old processes, they defined new ones that enabled them to introduce new products to the market. Process ownership was key.

• People. Another key result was the use of the system by end users. Step by step, each user adapted his or her behavior to the new system functionality and to the new processes. Any system is tested, measured, and evaluated by end users. In this particular case, in the beginning, end users at the branches were not engaged because they were not involved in the initial study, but their level of involvement grew in a positive way over a period of months.

• Technology. At the end of the project, all software modules in the new application were working, and the customer had a foundation platform for building future information systems for the new century. Technical results were improved over the old system. Performance was much better, and the system placed the customer in a position of technological competence within the financial market.

LESSONS LEARNED

We learned that the following factors are key for project success:

• Customer upper management sponsorship of the project is mandatory.

• Linking the project to the bank strategy was fundamental.

• Quality management was helpful.

• Communication planning and deployment was difficult but was key for the change agent.

• Encouraging end user participation is mandatory.

I found that I had to have different degrees of involvement in working with everybody on the team. The percentage of time spent working with people can be classified by project phase:

Initiation and Planning Phase

• 100 percent of my time was spent on scope validation and planning (time spent with the customer PM, team leaders, and other stakeholders).

Execution and Control Phase

• 75 percent of my time was spent on communication management (with the whole team).

• 40 percent of my time (weekly) was spent in project meetings (with team leaders, management, steering committee).

• The rest of my time involved planning, monitoring, and control.

Creating success in big organizations and on complicated projects like the Caja Granada change initiative, even if you have excellent leadership backing it, requires the involvement of many people, as well as time, patience, persistence and, especially, upper management support. An explicit change management process like the one we followed is an indispensable tool in the project manager’s toolkit.

Project Team Adaptability

A colleague and good friend, Michael O’Brochta, now operating as Zozer, Inc., shares this experience:

Even the best-laid plans in project management, no matter how carefully they are constructed, are subject to change. This was a revelation that came to me early in my project management career at the Central Intelligence Agency. In retrospect, I do not think the revelation about change came early enough.

At the beginning of my career in the spy agency, I drew upon my electrical engineering skills and the belief that the more I tried, the better I would become at precisely articulating the needs of the customer in well-crafted requirements that would stand the test of time unchanged. I dutifully listed requirements for tracking and locating devices that agents could use to maintain awareness of the whereabouts of all types of people and vehicles. I even added requirements to these lists that I derived based on my growing understanding of not just what the customer wanted, but what I understood that they needed as well. I got to be pretty good. I valued this reliance on precision; after all, I was an engineer.

I was naive. Things change. I could not control that fact. As I begrudgingly acknowledged my inability to control change, I proceeded into yet another self-delusion. I began acknowledging requirements changes but worked mightily to prevent them from being introduced into my projects. So what if the customer adjusted their needs? My view of my job was to be sure that my project was insulated from these changes to the degree necessary to proceed on schedule and on budget unscathed by the realities of change. I got pretty good at this too, proud of how I held my customer at bay while I drove myself and the contractors upon which I relied to stick with the original requirements lists.

Indeed, I did deliver many projects to completion precisely on budget and schedule and fully satisfying all the requirements. Problem was, some of these projects became “shelf babies.” The deliverables, be they tracking and locating devices or other types of spy gear, occasionally did not get used by the customer—they were placed on inventory shelves waiting in vain to be called into use. How could this be, I wondered? How could some spy gear that worked and met all requirements not get used? At this point my naiveté subsided and slowly was replaced by a bit of experience-based wisdom.

I came to understand that my job as project manager was not to prevent change … but to embrace it. I understood that my job as project manager was to manage the impact of change. I understood the need to establish methods and processes for managing the changes that would surely occur. I would identify the most likely changes as risks and develop responses to reduce the odds of the risks occurring and/or reduce the impact to the project if they did occur. I would establish baselines for requirements, and schedules, and plans, and anything else that was subject to change. I would manage by exception. If nothing changed, then I would proceed according to plan. When change did occur, then I would do a bit of analysis and determine the impact. That impact would be shared with others so that they could decide if the value of making the change was worth the resulting impact. I would act upon their decisions. At that time, I became aware of established methods and processes for the management of change; Mil-Std-973 for Configuration Management was a welcome eye-opener.

This was terrific stuff for a young CIA engineer who was emerging with project management skills. Revelation! My job was to manage change.

Inflexibility is one of the worst project manager failings. You can learn to check impetuosity and to overcome fear with confidence and laziness with discipline. But for inflexibility of mind there is no antidote. It carries the seeds of its own destruction.

Some project managers want to impose their habitudes and schedule when they work on a customer project. It is necessary to be flexible and adaptable to the customer schedule if you want to achieve customer team integration. We advise that wherever you go, you live as they live, eat as they eat, drink as they drink; otherwise, you will not be considered as an integrated part of the team. Teamwork and personal rigidity just do not mix. To work well with others and be a good team player requires being willing to adapt yourself to the team.

Project team players who show adaptability have certain characteristics. Adaptable people are:

• Teachable. They are people for whom temporary pain or discomfort means nothing as long as they can see that the experience will take them to a new level. They are interested in the unknown and know that the only path to the unknown is through breaking barriers. Adaptable people always place a high priority on breaking new ground. They are highly teachable.

• Emotionally secure. Projects are uncertain, and you must believe in project success in order to achieve it. People who are not emotionally secure see almost everything as a challenge or a threat. They meet with rigidity or suspicion the addition of another talented person to the team, a new activity, or a change in the way things are done. But secure people are not made nervous by change itself. They evaluate a new situation or a change in their responsibilities based on its merit.

• Creative. Creativity is the ability to put things together in new ways. When difficult times come, people find a way to cope. The ones who do not react with fear are the really creative people. They are people able to invent new ways to move forward and achieve results.

• Service-minded. People who are focused on themselves are less likely to make changes for the team than people focused on serving others. Doing nothing for others is actually the undoing of one’s self. If your goal is to serve the team, adapting to accomplish that goal is not difficult.

How are you when it comes to adaptability? If improving team performance requires you, as a project manager, to change the way you do things, how do you react? Are you supportive, or would you rather do things the way they have always been done before? The first key to being a team player is being willing to adapt yourself to the team, not to expect that the team will adapt to you.

Here are some ideas based on our experience that can help you become more adaptable:

• Get into the habit of learning. For many years, I (Bucero) carried a card in my pocket. Every day when I learned something new, I would write it down on the card. By the end of the day, I would try to share the idea with a friend or colleague and then file the idea for future use. This got me in the habit of looking for things to learn. Try it for a week and see what happens.

• Reevaluate your role. Spend some time looking at your current role on your team. Then try to discover whether there is another role you could fulfill as well or better than you do your current one. That process may prompt you to make a transition, but even if it does not, the mental exercise increases your flexibility.

• Think outside the lines. Many people are not adaptable because they get into negative ruts. If you tend to be prone to ruts, then write down this phrase and keep it where you can see it every day: “Not why it can’t be done but how it can be done.” Look for unconventional solutions every time you meet a challenge. You will be surprised by how creative you can become if you continually strive to do so.

Projects frequently change throughout their life cycle, and you need to adapt for the sake of your team. That way, you will always have a chance to be successful. Adaptability is a critical skill for complete project managers. Spend time training your team to be more and more adaptable too, and you will become a better project manager.

HELPING OTHERS RECOGNIZE A CHANGE PROCESS

Simona Bonghez, PMP, who works out of Romania, shares this dialogue explaining the learning process that she and her colleagues have experienced.

Simona: Traditional project managers focus heavily on project mechanics (tools and techniques), sometimes forgetting the human dynamics aspects: managing relationships and facilitating interactions. It has been proven that the rate of success can be raised if more attention is given to handle the interest groups, whose support is needed or whose opposition needs to be overcome. Of course, we are talking about stakeholders, people and groups with an interest in the project and who can affect the outcome; they may promote the project within the organization and actively support it, but some of them may also perceive it in a negative way and therefore act against it.

I would like to give an example, the case of an organizational development project within a construction company. A professional with a high level of expertise in technical disciplines of engineering and technology was nominated to take over the responsibilities of managing this complex, internal project. He was highly technically proficient and very good at motivating a team; however, this project presented him with a major challenge as stakeholder management and communication were quite “exotic” for him.

PM: It was a huge difference from the projects I used to be involved in (construction projects), an obvious twist from focusing on “hard” skills to handling “soft” skills. The fact that communication is “touchy-feely” and wastes time is a myth; for this project I needed to gain the commitment and involvement of both management and employees of the organization, and the only “weapon” I had was communication. I learned—the hard way—that in order to be effective I have to identify all relevant interested parties, to understand their requirements and expectations, to anticipate their reaction, and—the most difficult part—to influence them.

Simona: What do you consider the most essential interpersonal skills the project manager needs to use in order to influence others to act in a particular way?

PM: Well, for me, the most essential interpersonal skills were communicating and understanding change management. I had to communicate with top management in order to gain their continuous support and to keep this project among those with high priority. I had to communicate with the directors and functional managers in order to assure them that the changes had no negative implication on their positions, to allow them to understand the changes in their responsibilities and help them to accommodate. Some of their ideas were incorporated in our project, some of their initiatives had to be stopped, and each of these actions had to be justified, planned, properly communicated, and implemented.

Simona: So, stakeholders’ management does not only stand for another sociological interaction with the project management field; its results are visible in several “pure” project management aspects, such as planning of resources, of quality, change control. It clearly translates into quantitative and qualitative indicators and results. Do stakeholders’ analysis by the project manager in the early stages of the project, document and present their requirements and expectations to the team. After the stakeholders’ interests are assessed (as well as the way that those can—positively or negatively—affect the project), develop a plan for managing relations with them—gain their support, minimize opposition, and generally create a favorable climate for the project.

PM: And this is not enough—stakeholders have varying levels of responsibility and authority when participating on a project, and these can change over the course of the project’s life cycle; their expectations can change or be in conflict with other stakeholders’ expectations. At the beginning of our project, one of the team members was an important supporter of the project, but as things evolved, he realized that the project would affect his position in a way that was not expected and, feeling threatened, he started to disrupt things. I learned that I should be vigilant, not take the current position of the stakeholder as certain and be alert to external changes that may shift that position. Stakeholder management is a continuous responsibility of the project manager throughout project life cycles.

Simona: Stakeholder management and communication is a project management approach that twists the focus from project “hard” skills (content-related activities) to project “soft” skills (relational aspects). Of course, both dimensions are essential and should be well balanced. In order to attain this goal, it is necessary for the professionals dealing with projects to become aware of the fact that stakeholders’ management tools represent a necessity with proven effective results.

Remco Meisner shares the following episode to help others recognize the impact of change, assess the temperature of an organization, and understand what a complete project manager needs to do. Note especially how he shapes the dialogue through carefully crafted questions:

At the startup of the project at a governmental organization, Wim came to me and asked for my opinion. I had known him for about a decade, and I could detect a certain tension when he asked, “What do you think, can the project be handled in three months or so?”

Remco: I have dealt with projects like this that took only a couple of weeks. In order to provide a proper estimate, I will need more details. I know, for example, that this ministry has had several organizational changes in a row during the past five or six years at least. This might have not influenced their eagerness, but to be honest, I am concerned that the people are exhausted after what has happened in that time frame.

Wim: Yes, I think a lot has happened over the last few years. The last half year really was something else. We recently announced a new procedure that will require nearly all the staff to change the way they conduct their work. We had to do that, you know, because of the political choices that the new government made. Until last month, we were busy implementing a new planning tool. This took much more time and effort than we had anticipated. We still are not fully satisfied with the end results. It has drained our front-line workers, and they obviously also feel the friction between what we had hoped to get and what actually came out of the process.

Remco: I spoke to Peter the other day, and he told me a little about this. He also said that there are major construction changes underway to all the buildings, spread all over the country. We had that fire in one of the buildings a couple of years ago, where there were casualties and people seriously injured. That triggered a lot of attention in the media. Nearly seventy buildings in the country as a result will now need an upgrade of the fire protection measures: new window fittings, a change of all doors, metal constructions, and so on. Doing all that requires the people working and living there to be temporarily relocated. This puts a strain on our staff and on those inhabitants. It will increase tensions, and there might be some friction due to the fact that people will feel cramped. Besides, we hardly have sufficient room for the intermediate housing of all these people.

Wim: Yes, there are a couple of things that will overcome us all during the next year. All put together, that doesn’t sound too appealing regarding that three-month time frame, now does it?

Remco: Well, it may turn out not to be a disqualifier yet. The last time I did this software development thing for you, we had to tackle it with a couple dozen external analysts, programmers, designers, testers. As I recall, your organization was not too experienced in dealing with complex projects—where there are many specialists temporarily involved from several sources and working along a tight schedule. No wonder you are not experienced, since that simply isn’t your core business, is it? Doing such projects is really an exception to the rule. Nevertheless, it was an eye-opener at the time, that there were more complications there than the ministry had initially anticipated.

Wim: That was quite a project now, wasn’t it? But we managed to pull it off. I remember now how difficult it was to get the ICT department and the people in the project to cooperate. They really were different characters: the project crew ready to innovate and renew the whole lot, opposite the ICT department trying to catch it all in their existing procedures and service-level agreements. It just did not fit in! And they had little experience in dealing with projects of this volume and complexity. I fully agree with you there.

Remco: Something that also struck me the last time we did a project together comes to mind. The board of directors in The Hague was at one end of the line and the directors of all these nationwide spread units were at the other. They had very different opinions regarding the way to conduct business, didn’t they? The Hague declared a change of organizational structure, which after a struggle got accepted by all those different directors. In the end, however, the directors succeeded in reverting back to the original structure, unnoticed by the board, so that it in fact once more complied with their original ideas. I think this is typical for a government organization, so I am not complaining. But it struck me as interesting at the time, as it would not work like this in private organizations.

Wim: Well, we do have a legacy in this area. This is the way it has worked for decades. These people in The Hague don’t really know all that well how to deal with the depth of field issues and they, with the best intentions at heart, decide this or that, which, in the long run, is more or less ignored in the outer fields. Or, at best, it is adjusted slightly, a couple of times in a row, so that in the end it will have been altered completely.

Remco: So, there is a certain rigidity in the organization?

Wim: Yeah. There is. Usually it’s for the better.

Remco: So, if I get it right, you have here a complex project that you would like to get finished in a couple of months from today?

Wim: That is it!

Remco: Hold on. I’m not finished yet! (They laugh.) You had a busy year, and also before the last year it was not really a serene and relaxed period, was it?

Wim: Nope.

Remco: There were new tools implemented, which took a lot more effort, time, and money than had been anticipated. And you’re not really impressed by the end results?

Wim: That’s true. We believe it is unfinished yet.

Remco: Then there are all these construction works going on, due to political pressure, in order to prevent a fire incident from ever getting out of hand again. This will have impact on all units, spread all over the country. It will really put pressure on the people there, because they will have to move all their groups around, in order for the workers to be able to mend the fire protection gaps in the metal constructions, the window fittings, the doors, and so on.

Wim: Yes. I think that will have a major impact on their work pressure. We haven’t got all that much room to move around in …

Remco: And my final point is that you have little experience in dealing with complex projects like this one. The people in the units and in the central office are not used to dealing with these major changes. This requires a complex planning scheme, since we will have to work throughout the country with yet another in-depth alteration to the daily routines. The new routine will succeed previous ones and will turn upside down the current functions, hierarchy, and rewards systems.

Wim: I get a hunch feeling of what will be coming next.

Remco: The organization is change-tired, having had to deal with major change in a constant sequence over the past year. This change that we are talking about now will impact their foundations, as it will influence the function titles, reward system, the information systems handling it all, the planning method …. (A short pause here.) The same planning system, I gather, that you are not yet fully satisfied about as it is?

Wim: That’s true. There will probably be some alterations and upgrades in there too.

Remco: Alterations that your organization, regarding the project-oriented approach, is not yet well equipped for as it is. Complex changes are required, involving multiple units and all kinds of experts in various areas that will have to work together and find consensus on countless topics, each of which in turn may cause the whole construction that we have in mind to tumble over.

Wim: So, you think three months is too short?

Remco: So, I think three months is too short. We might be able to pull it off on short notice. But the signs are not encouraging. It will probably be better to base timing on a more realistic schedule. We really must refind our balance on the current stepping stone that we landed on, thinking carefully over what to do next, before we jump to the next one. If we don’t, I think we may tumble and end upside down in the water.

Wim: What is your advice?

Remco: We should learn from what has been accomplished so far. Next, we need to investigate what steps are to be made in order to implement these changes for one single unit. This will be our casting mold. While we do this, at the same time, we will need to find out what are the time frames of the other projects. Where do we all intersect, and what is the smartest option there? I mean, who gets the first green sign, who will be next, and so on. Also, we need to find out how difficult it is to change the ICT in order to deal with this new structure. And we will need to find out what the impact will be on all those applications that we are using nationwide. I suppose they still use that same lengthy list of software that I encountered the last time round?

Wim: Yes, but we are working on that.

Remco: I know. Taking many of them out is not an easy task. These units have been allowed privileges in the past, and we both know how easy it is to accept an increase of privileges. It is much more difficult to deal with the lessening!

Wim: We had a lot of them taken out of the operational list. And we spread the word explicitly after that step. But if you check the situation in the field, you can still find units using outcasted software on a daily basis.

Remco: I know. Let me add this advice: we should hook up to the management team in The Hague as well as to that of the units. We need a proper blueprint of where we want to end up. We need to determine what are our success and fail factors and what is the starting temperature. It is a cold starting situation, I think, due to all the change tiredness. And how will we get all the people whose daily work will change involved in the project?

Wim: So, we need a change approach?

Remco: Yep. We need a change approach. And since this is a project-oriented environment, at least that is what this organization prefers for its approach, we need to stipulate a couple of projects to deal with the various areas that will be hit. The change approach will provide for a link to the directors at the various positions, and it will aid in getting decisions made and keeping track of it all. The project approach will deal with the planning, which might be one project. Another project will be the personnel systems. A third project will be the various applications used in the field. The SAP system and all financial dataflows leading to and from will be project number four. And project number five will deal with the works council and the unions. This last project will hardly comply with the definition of a project, as it will be a ferocious sequence of steps, but we can slice it down to something resembling a project if you prefer.

Wim: When can we start?

The above narrated story, which closely resembles the actual dialogue between Remco and Wim, is an illustration of the way change management and project management skills come in handy in the case of major organizational changes that initially are addressed (by the customer) as if they were standard projects.

Change management is another discipline compared to project management. There are resemblances, since they both deal with temporary organizations, the accompanying structure, often involving external experts, a (usually tight) budget, interaction with management teams, and so on. But there are as many substantial differences too.

In a change management situation, it is necessary to consider the starting position of the organization involved. Has it encountered a whole series of (sequential) changes over the past months or years? This will influence the way people in the organization will or will not be able to absorb yet another change. If the organization has been stable or has had to deal with only minor alterations, it may be considered “warm.” Warm in this respect means the organization will be able to deal with novelties, and people won’t easily swap their perspectives on the work into negative ones. In the case of a “cold” organization, employees are tired or exhausted from having to deal with predecessors. If this perspective is not taken into account at the start of a project or program, the result might well be a mutiny. In any case we won’t get much help.

In a change management situation, we also need to consider success and fail factors of the organization. What are they good at (success factors) and what more should they be able to take on, even if they themselves don’t see that as clearly as we do yet? To which things or activities do they respond poorly (fail factors) and what should we, for that reason, avoid involving them with?

We also need to consider the “theory of the business” (Peter Drucker). What is the idea behind the organization? On what basis did they start, develop, and survive and, next, what is their set of assumptions under all that?

And, most important of all, we need to consider the fact that change management considers organizations whereas project management usually deals with things. Admitted, we of course do consider people with our projects as well, but there is a significant difference in the approach of project managers compared to that of change managers.

Change managers have to seduce employees and business relations to move from A to B or C. As soon as there are things involved in relation to their quest, those turn into projects.

Project managers are concerned in developing new things, or moving them about, or changing them. As soon as there are people involved, those closest to the things will be taken into account (at least, a solid project manager will do that!), but in a project usually not the whole group of employees in an organization will be considered.

We will not be allowed to call a cat a dog and the other way around. We won’t get shot for calling a project manager a change manager or vice versa. We may decide to start a project that in fact is an organizational change but is not to be named as such as that might immediately prevent it from taking off. But if we seriously try to be as pure and undiluted as possible, the above stated is true.

Ideally any project manager aiming for involvement in complex projects should know at least the highlights of change management. Any project, large and small, can benefit from such a project manager. We often tend to forget the fact that things and individuals are correlated in many ways. We, project managers, will be able to shift our performance and the appreciation that we harvest from one project to the other by studying change management and considering all the wonderful new insights that it offers us.

GENERATIONAL CHANGES

Multigenerational staffing is happening, probably more so than ever before, due to longer life spans and more older generations staying in the workplace longer. Elsewhere, we covered the challenges and opportunities represented by millennials at work. Changes in perceptions and preferences happen, whether we like or agree with them or not. Complete project managers need to embrace and prepare for the next generation.

Among his list of ten skills for next generation project management and PMOs, Jack Duggal was asked, “When is the next generation coming?” He corrected his initial response, “the next generation is never coming,” to “it is always coming…. The next generation is not a destination, it is a journey without a finish line.”

Much like we characterize a complete project manager, Duggal says, “A good mantra for the next-generation project, program, and PMO managers is ABCD: Be Constructively Dissatisfied. Always questioning, inquiring, challenging … is there a better way … how can we do better? … Be the bridge between the old and new. The traditional must be sustained to ensure stability while preparing the organization for change and agility … constantly challenge yourself—how can we better adapt to changing needs, how can we better serve our customers and organization, and how can we add greater value and create long-term sustainable impact?” (Duggal 2018, 258–259).

We heartily agree with and support Jack’s advice.

Summary

The complete project manager takes the time and effort to understand why people seem to resist change and integrates change management skills into their “molecule.” The keys to dealing with change successfully are having a good attitude toward it and being prepared to meet it. Understand the change management process: create the conditions for change, make change happen, and make change “stick.” Clarify roles in the change management process, and get targets of change involved in deciding upon or planning implementation of change.

Change will happen whether you like it or not. Without change there can be no improvement. Complete project managers make a commitment to changes. That includes being adaptable to new situations and ways of doing things. Learn from experiences of others how they successfully dealt with changes.