Chapter 2

Employee Stock Options

A User’s Guide

Suppose you have two job offers—one with employee stock options (ESOs) and the other without. The offer without ESOs has a flat $80,000 base salary, and the other is for $40,000 in base pay plus $40,000 in ESOs. By market value, they are both the same. Sure, the ESO alternative could make you very wealthy if the company’s share price rises, but you could also end up with only your $40,000 base salary if the share price falls, remains constant, or does not rise quite enough. Which would you choose? How would you go about making your decision? Does it make a difference if your employer is a well-established company or start-up? How might your age and family situation play a role? Why is it likely that the value you put on ESOs is far lower than the value your employer puts on them? Are there some insights that can improve your bargaining power with a prospective employer?

Employers have similar questions. Why would a company offer ESOs instead of a flat salary? Does it make a difference if the enterprise is well-established or a start-up? Are there better ways to motivate employees? Are ESOs in the best interest of existing shareholders? Should every employee get them or just those with a major influence on the company’s share price?

This chapter answers these questions and provides logical ways to sort out whether ESOs are right for you. It probes the advantages and disadvantages of ESOs, from both employee and employer perspectives, as well as providing an overview of the major issues so you can form your own opinions about this form of compensation. As you might expect, answers depend, in part, on the individuals and companies involved. People who seek, welcome, and accept ESOs compensation reveal a lot about their tolerance for risk, and companies that offer them reveal a lot about the incentives they believe will motivate their employees.

ESOs: A Major Pillar of Executive Compensation

Executive compensation typically is composed of four pillars: a base salary, an annual performance bonus, stock options, and a long-term incentive plan.12 The stock option component of these compensation plans is usually in the form of call options, which give an employee the right, but not the obligation, to buy a company’s shares at a predetermined price (called the strike price or exercise price) during a given period of time (or on a given date in the future).

If the stock price remains at or below the strike price, the options expire worthless, and the employee ends up earning just the base pay. If the stock price rises above the strike price (i.e., the options are in-the-money), rewards can be significant.

One of the benefits of owning calls is the presence of considerable upside potential and absence of downside cash-flow risk. If the share price rises, you gain for each cent the underlying share price moves above the strike price, and potential rewards are unlimited. If the share price falls or remains below the strike price, you pay nothing to your employer. Of course, eliminating this downside risk is of little comfort to those who sacrificed higher paying jobs elsewhere for the chance to strike it rich with options in their current jobs. Because the final values are so uncertain, stock options are less attractive to individuals who are risk-averse13 or foresee declining economic activity (e.g., a recession). By contrast, more adventuresome individuals might prefer having elements of risk offering upside compensation potential.

Why Do Companies Use ESOs?

Companies using stock options in their compensation plans usually do so for one or more of the following reasons: (1) aligning incentives, (2) hiring and retention, (3) adjusting compensation to employee risk-tolerance levels, (4) employee tax optimization, and (5) cash flow optimization.

Aligning Incentives

Economics and Finance literature have long acknowledged that most large corporations are managed by executives who, for the most part, are not major shareholders. As a result, managers’ goals may not be the same as the goals of shareholders.14 The hope is that, by giving employees a piece of the corporation, ESOs will build membership and commitment, encourage employees to constantly refresh their skills, and promote decision-making that is consistent with corporate strategy and with the ultimate goal of maximizing shareholder value. The fear is that, without such incentives, employees will pursue more self-serving goals, such as increasing their salaries and power bases, extravagantly beautifying their workspaces, as well as excessively entertaining clients and traveling at company expense.

Logic dictates that the more opportunities a company has to invest in value-adding projects, the more important it is to have an incentive system that encourages employees to maximize shareholder value. In fact, empirical evidence supports the claim that companies with greater value-creating opportunities (i.e., projects that contribute to shareholder value) make greater use of ESOs than those that do not have such growth prospects.15

Hiring and Retention

Stock options may be essential for hiring and retaining first-rate employees. Many companies feel that offering ESOs is necessary in an environment in which competitors offer them.

To more tightly bind employees to a company, many stock option plans have vesting periods, which require employees to wait one to five years (or more) before they can exercise their options and harvest the rewards (assuming there are any). In fact, numerous human resource executives and analysts believe that lengthening both the maturity and the vesting periods of ESOs are excellent ways to retain key people because they increase an employee’s cost of leaving and raise the stakes for covetous competitors trying to hire away quality talent.16

Without stock options, young, fast-growing, cash-strapped companies would be hard-pressed to compete aggressively for top-notch employees against established, well-financed competitors. If they are not hedged, a company is burdened with no cash outflows when the options are granted. Furthermore, when they expire or are exercised, the magnitude and timing of any negative cash flow effects depend on whether or not the options expire in-the-money, the company has hedged its exposure, and the company issues new shares to satisfy the demand by option-exercising employees.

Adjusting Compensation to Employee Risk Tolerance Levels

The quantity of stock options paid to an employee as compensation depends on two major factors: the price of each option and the total value of the option compensation. For instance, if you were awarded $40,000 in stock option compensation, and each option was worth $1.00, then you would receive 40,000 options. If the price of each option were $2.00, you would receive only 20,000 options. Calls that are out-of-the-money (i.e., their strike prices are higher than current market prices) have relatively low values because they have less chance of expiring in-the-money.

Companies have the flexibility to choose strike prices that they believe will motivate their employees, but this choice is a double-edged sword. The higher an ESO’s strike price, the lower the value of each option because the options have less chance of paying anything. Due to their lower value, employees must be given more stock options for any predetermined level of compensation. By contrast, a lower strike price increases the option’s value, which means that employees receive fewer of them for a given level of compensation, but the chances are greater that the options will be worth something when they expire. By varying the strike price, stock option plans can be adjusted to accommodate different individuals’ preferences for either secure income or uncertain future gains. Young, single, energetic college graduates might eagerly choose options that are dramatically out-of-the-money because their lower value means getting more of them. If the share price rises substantially, these young employees could become very wealthy before the age of 30. By contrast, married employees with children in college and large mortgages might prefer much lower strike prices and much more secure sources of income.

Employee Tax Optimization

The tax treatment of ESOs varies from country to country. Nations, like the United States, impose no taxes on ESOs when they are granted, unless the options have intrinsic value (i.e., issued in the money), but then tax any realized appreciation when they are exercised. In nations where stock option appreciation is recognized as a capital gain (and not as ordinary income), ESOs are especially attractive because the tax rate on capital gains is often much lower than the tax rate on ordinary income. The take-away point is always to check about the treatment of your ESOs. It is important and can be messy.

ESOs offer recipients considerable control over the timing of their realized earnings. Employees who exercise their stock options can choose either to purchase company shares at the strike price or simply to cash out their profits and earn the difference (per share) between the stock’s market price and its strike price. In the United States, when stock options are cashed out, the gains are treated (usually) as ordinary income and taxed at ordinary income tax levels. If employees exercise their options, purchase company shares, and continue to hold them, the profits on any further share appreciation are taxed at the capital gains tax rate, which is lower than the rate on ordinary income.

Cash Flow Optimization

ESOs become more valuable only if the share price rises above the strike price, and a rising share price usually corresponds with favorable company performance and favorable expectations about future earnings and cash flows.

The cash flow effects of ESOs should be evaluated at three crucial points: when they are issued, when (and if) they are hedged, and when they are exercised or expire. At issuance, the cash flow effects depend on whether the options are hedged or not. At exercise (or expiration), the cash flow effects depend on the combined conditions of whether or not the options are in-the-money and whether or not the options were hedged.

Cash Flow Effects at Issuance

Regardless of whether ESOs are issued at-the-money, in-the-money, or out-of-the-money, they have no immediate, explicit, negative cash flow effects on the issuing companies. In fact, they can be thought of as providing implicit cash inflows because these options are used as substitutes for higher outright compensation.17 Nevertheless, if companies cover the exposures created by their ESOs (i.e., cover their short call positions) then there are cash outflows when the hedge is implemented. Companies that offer ESOs have short call positions, which means they can protect themselves by purchasing call options, if available, or buying their own shares in the open market. These hedges require cash payments at the time the hedges are implemented, equaling the price of the call option or share times the number purchased. The increased demand for shares should put upward pressure on their prices, but simultaneously, by depleting its cash assets, the book value of the company should fall.18

Cash Flow Effects at Exercise or Expiration

If a company has not hedged its ESOs and they expire in-the-money, cash flow effects can be positive or negative. Suppose the ESOs had a strike price of $100 per share, they were exercised when the market price was $150, and employees wanted to own the shares. If it did not issue new shares, the unhedged company would have to pay $150 per share to acquire them in the open market, and then transfer each of these shares to option-exercising employees for only $100. The net effect would be to drain the company’s cash reserves by $50 times the number of exercised stock options. Alternatively, if employees had no interest in purchasing shares and wanted only a cash payment, then the company would not need to purchase shares in the open market and would simply make a net cash payment to the employees of $50 per exercised option.

If the options expired in-the-money and the company issued new shares to meet the demand, there would be net cash inflows because the company would issue new equity and receive an amount of cash equal to the number of exercised options (i.e., shares purchased) times the strike price. The cash proceeds would be added to the company’s current assets and paid-in capital, and the number of outstanding shares would increase.

If the share price remained at or below the strike price, the options would expire worthless and there would be no negative cash flow effects at expiration. Similarly, if a company hedged its employee stock options, cash outflows from the exercised options would be offset by the hedge, and there would be no negative cash flow effects. This is rarely done.

One potential problem with ESOs is they often have long maturities and extended vesting periods, which could inhibit a company’s ability to issue new options in the future because old issues are waiting to mature or be exercised. Companies may prefer shorter maturities and more limited vesting periods so that ESO owners become shareholders.

Option Valuation Differences and Human Resource Management

Stock options can create two different images of the same reality. An example of this illusion occurs when current or potential employees value options differently from the companies offering them. These discrepancies can mean the difference between landing or retaining quality talent or losing it to competitors—often after extended searches and investing thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours in fruitless recruitment efforts.

To better understand the illusion created by options, imagine yourself trying to decide between two attractive job offers. One position offers you pure salary compensation, and the other is a combination of salary and stock options. How would you go about deciding which one to accept? To make the choice even more interesting, suppose that, on paper, the salary-with-options offer is about 10 percent higher than the pure-salary offer. The following dialog puts you in the shoes of someone who was in just this position. It explains how she systematically decides which offer is better for her. In the process, you will gain a better appreciation for the way in which many companies arrive at the values they put on ESOs and how these values may be quite different from the value employees put on them. Hopefully, the ideas that emerge from this dialog will be helpful to you if (and when) you negotiate a future contact.

Helvetia Holding, a pharmaceutical company located in Boston, Massachusetts, spent nine months identifying the scientist it wanted to head corporate-wide research and development activities, but the candidate was also being pursued by Zentrum Inc., an equally important U.S. pharmaceutical company located just minutes away in Cambridge. Knowing that Zentrum was offering an outright salary of $550,000, Helvetia countered with a total compensation package worth $600,000: $400,000 in outright salary and $200,000 worth of stock options. Imagine the surprise of Helvetia’s human resources chief when the scientist turned down Helvetia’s offer because she found Zentrum’s deal to be financially more attractive. You might ask: “How can two people put such different values on something so seemingly cut and dried as an option’s price?”

To understand the answer to this question, roll back the clock to the day before Helvetia made its employment offer. It is likely that the director of human resources understood very well the benefits, costs, risks, and returns of call options, but he had no idea how to value them. For that, he relied on Helvetia’s treasury department. Tune into the conversation between Daniel Weiss, Helvetia’s human resources chief, and Tom Benson, Helvetia’s assistant treasurer, that took place the day before the offer was made:

Daniel Weiss: Tom, thank you for coming on such short notice. I would like to know the market price of a call option on a Helvetia share as quickly as possible. Can you help me? How long do you think it will take you to figure this out?

Tom Benson: I’d be glad to help, Daniel, and once we agree on a few details, it will take me only a minute or so to enter the information into my computer and figure out the market price of the option, but first I need some information from you. The price of any option depends on six major factors: current share price, the exercise (or strike) price, maturity, expected share price volatility, risk-free interest rate, and expected dividends. I came prepared with most of this information, but I need to know from you the maturity and strike price.

Daniel Weiss: All right. Helvetia’s current share price is $50; so, could you tell me the price of a five-year call option that has a $50 strike price?

Tom Benson: Fine, then you want to price a five-year, at-the-money call option. That’s all I need to know. Let me just summarize the six variables we will be using in our calculations, in a table, just to make sure that what I’m entering into my computer is transparent to you.

| Helvetia Option Pricing Information | |

| Current share price | $50 |

| Strike price | $50 |

| Maturity | 5 years |

| Volatility | 35% |

| Risk free interest rate | 4.75% |

| Dividends | $0 |

Based on this information, the Black-Scholes-Merton (BSM) formula tells us that the market price of this option should be $19.49.

Daniel Weiss: Just for comparison sake, could you tell me the price of a 10-year call option with the same $50 strike price?

Tom Benson: With a 10-year maturity, an at-the-money call option should have a market price of $27.84.

Daniel Weiss: OK. Give me just a second to write down this information. That was much easier than I thought it would be. Thanks for your help, Tom.

Armed with this knowledge, Daniel Weiss could now make his offer to Jennifer Smith, a research professor at M.I.T. and head of R&D at Bio-Pharm Associates in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Weiss figured that if an at-the-money five-year stock option was worth $19.49, and he wanted to compensate Smith with $200,000 worth of stock option benefits, the compensation package should include 10,262 stock options.19 To ease the math and sweeten the deal, Weiss rounded the offer at 10,500 call options. The next morning, he called Jennifer Smith and made his offer. As he explained the offer to her, Weiss stressed that Smith would get raises each year and additional stock options in proportion to her salary.

Jennifer Smith had been anxiously awaiting Weiss’ call because Zentrum was actively pressuring her for an answer. Weiss explained to Smith the calculations behind his offer of a base salary of $400,000 and 10,500 call options, and he volunteered the services of Tom Benson if she had any technical questions about how Helvetia valued her options. Smith had no immediate questions about the offer or the option valuation. At first glance, Helvetia’s offer looked very attractive. “Imagine,” she thought, “being offered over $50,000 more than Zentrum. How can I say no?”

Because Jennifer Smith didn’t understand the nuances of option pricing, she wasn’t sure how to reply to Weiss’ offer. All she could think to ask was whether the options had any restrictions, like a vesting period. Embarrassed by the oversight, Weiss answered that all of Helvetia’s ESOs had three-year vesting periods. Smith knew from experience that this was normal.

From her years in the corporate world, Jennifer Smith had earned a stellar professional reputation using her mind in clever and ingenious ways, but on numerous occasions, she had been saved from disaster by her instincts. In this case, her instincts were flashing red. Jennifer’s mind was telling her that the Helvetia offer was head-and-shoulders above the Zentrum offer, but if that was the case, why didn’t it seem $50,000 better to her? Something wasn’t right, and she protected herself by asking Weiss for a few days to think over her alternatives. Weiss reluctantly agreed to a three-day decision period.

It took Smith only a day to reach the conclusion that Helvetia’s offer was not as financially attractive as Zentrum’s offer, and by the time she called Daniel Weiss, she had already accepted Zentrum’s contract. Weiss was staggered. He was so sure she would accept his offer that he had already notified the CEO to include her name in Helvetia’s organization chart. How could Helvetia’s offer of more than $600,000 not be as attractive “financially” as a competing offer for $550,000? Weiss asked Smith if he could call her later that day. Realizing that he had lost the battle with Zentrum, he didn’t want to make the same mistake again. He called to see if Tom Benson could participate in the conversation. Benson was glad to help and curious about what happened. Later that day, here is how the conversation went.

Daniel Weiss: Dr. Smith, we are very disappointed to have lost you to a competitor. Are you sure there is nothing we can do to change your mind?

Jennifer Smith: Thank you, Daniel, but no. I’ve accepted the Zentrum offer and am happy with my decision.

Daniel Weiss: I have Tom Benson on the line, just so he can help me piece together what went wrong. You will remember that Mr. Benson helped me value your stock options. Did I tell you that we used the BSM formula to do our valuation?

Tom Benson: Hello, Dr. Smith. Thank you for allowing me to be a part of this conversation. I’m as interested as Mr. Weiss in understanding how you arrived at your decision.

Jennifer Smith: I realize you both must think I’m crazy—especially when Nobel prizes were given to the gentlemen who developed the BSM formula, but all I can say is that what the formula says Helvetia’s options should be worth is not what I feel they are worth to me. Here’s how I arrived at my conclusion. First, let me preface my remarks by admitting that I had some help making up my mind. After our call yesterday, Daniel, I phoned an old friend, John, who teaches at a nearby college. John and I met last night for dinner, and he sorted out some of the technical details for me. The first question I asked him was if there was any way I could lock in immediately the $200,000 of stock option compensation that Helvetia was offering.

Daniel Weiss: That sounds logical enough. What was his answer?

Jennifer Smith: He explained that my call options gave me the right to buy Helvetia shares for $50 any time after the three-year vesting period. One way to lock in the value of the options would be to sell short the Helvetia shares—which I now understand means that I would have to borrow shares, sell them at the current market price, and agree to return them in the future.

Daniel Weiss: I’ve heard of short selling but never really understood what it meant. Usually, when I think of someone making a profit, I think in terms of buying something today and then selling it in the future at a higher price. What you would be doing is just the opposite: selling Helvetia shares today and then buying them in five years at the price guaranteed by your stock options. It’s sort of like closing the loop—selling now and then buying later.

Jennifer Smith: Exactly! But once I sold the shares short and collected the proceeds, I’d invest the funds in a safe asset, like a U.S. government bond. My Helvetia options had five-year maturities, so I based all of my calculations on investing the funds until maturity.

Daniel Weiss: But, Dr. Smith, would it be legal or ethical to sell short Helvetia’s shares in this way? I also believe our company prohibits it.

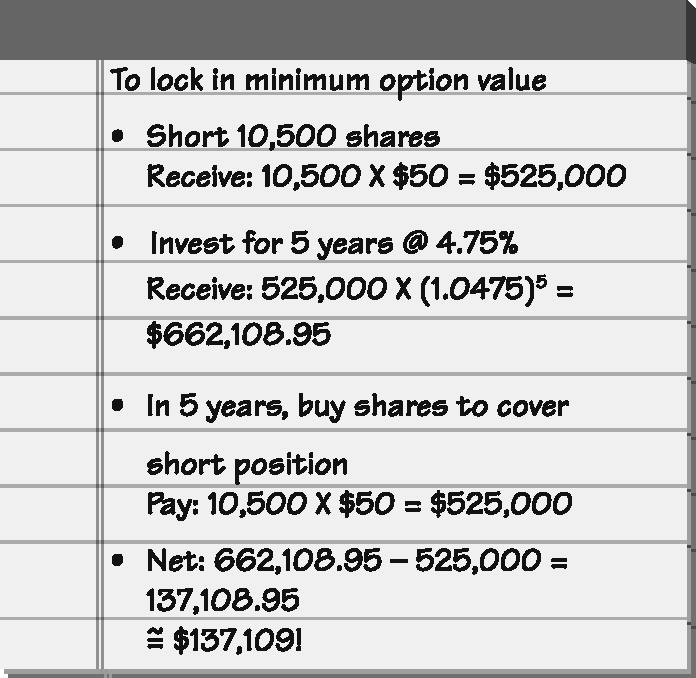

Jennifer Smith: Yes, that’s true, but my point is that even if I could sell short the Helvetia shares, I figured that the most I could lock in—assuming Helvetia shares rose in value, which I’m sure they will—would be only about $137,100, and to do that, I’d have to wait five years! Here’s how I did my calculations.

If I sold short 10,500 Helvetia shares at $50 per share, I’d receive $525,000, which I could invest for five years. Currently, a five-year U.S. government bond yields 4.75 percent; so, $525,000 invested at a compound annual rate of 4.75 percent would grow to $662,109 in five years. At the end of the five years, if Helvetia’s share price rose above $50, I would exercise my options, spend $525,000 to buy back and return the 10,500 shares that I borrowed, and have $137,109 remaining.

Daniel Weiss was frantically writing all of this on his pad. He now understood how Jennifer Smith derived her figures, and he was relieved by the thought that he could review his notes later with Tom Benson. Her math made sense. Nevertheless, he called on Tom Benson for confirmation.

Daniel Weiss: Mr. Benson, do you agree with Dr. Smith?

Tom Benson: Yes, I do. Here’s the problem. An option’s initial market value can vary within minimum and maximum limits. The $137,109 figure that Dr. Smith calculated as the amount she could lock in if she sold short Helvetia’s shares, works out to $13.06 per option. Discounted, this equals $10.35 per option, which is close to the minimum initial option price. The maximum initial ESO price is Helvetia’s current $50 share price. The BSM formula, for reasons we will not get into here, calculated a market price for the Helvetia option equal to $19.49, which is within this minimum-maximum range. Actually, if Dr. Smith wanted to cover her position, all she could hope to do is to lock in a range of possible future payoffs with $137,109 being the minimum.

Daniel Weiss: If $137,109 is the minimum she could lock in, then how could she earn the maximum value?

Tom Benson: Well, here Dr. Smith has been very diplomatic. To earn more than $137,109, the price of a Helvetia share would have to fall below $50 when she exercised her options in five years, and to earn the maximum, the Helvetia share would have to fall to $0.

Daniel Weiss: I see. The calls give her the right, but not the obligation, to buy Helvetia shares in five years at $50. If the share price fell to $0, the options would expire worthless, and she would pay nothing to return the borrowed shares. At the end of five years, the entire investment (principal and interest) of $662,109 would be hers to keep.

Tom Benson: Exactly.

Daniel Weiss: Dr. Smith, I’m no expert on hedging, but I’ve always thought that to hedge, you had to take a position the exact opposite of the one you had. In other words, take what you have and do the opposite. Because Helvetia would be compensating you with long calls to hedge this position, I thought you would want to sell options with the same strike price and maturity.

Jennifer Smith: Daniel, you’re absolutely right, and yes, John and I discussed the possibility of shorting call options on Helvetia shares last night. Here’s the problem. Helvetia has exchange-traded options in the United States, but they do not have the same maturities or strike prices as the ones you would be giving me. Even if they existed, John told me that I would be exposed to a sizeable cash risk due to margin calls.

Daniel Weiss: Margin calls? How is that a risk? The gains from your Helvetia calls should exactly offset the losses on your hedge—or vice versa. No?

Jennifer Smith: In the long run, you’re right. It’s true that eventually the gains or losses from my Helvetia options would offset the losses or gains from my hedges, but in the short run, I could be in for quite a financial roller-coaster ride. The problem is that if Helvetia’s share price rose rapidly, I’d be rich on paper because my long calls on Helvetia shares would be in-the-money. In other words, they’d have a lot of intrinsic value, but I wouldn’t collect these profits until I exercised the options—and that wouldn’t be for three to five years from now. In the meantime, the exchange-traded options—my hedges—would be repriced daily and their rising price would require me to constantly feed margin to my broker. It could end up draining all of my savings!

Daniel Weiss looked down at the notes he had made on his memo pad. There were only three major points, but a voice deep inside told him that there was more to come.

Daniel Weiss: Dr. Smith, you have been very thorough, patient, and generous with your time, but sometime today I’m going to have to explain to my boss how we lost you; so please answer just one question. How was it possible for Helvetia to offer you over $50,000 more than Zentrum but for you to feel that the Zentrum offer was financially more attractive? Is it just because Zentrum was offering you a sure thing, and we were offering you a degree of uncertainty? Did you consider that the uncertainty of our offer also contained the opportunity to strike it rich and become a millionaire?

Jennifer Smith: I assure you that becoming a millionaire didn’t escape my attention, but the fundamental problem I had with Helvetia’s offer was that the price you put on the options was not equal to the value I put on them. Even after figuring in the advantage I would have over anyone outside the company with regard to timing the exercise of my options, your offer came up short.

Daniel Weiss: We—and by “we” I mean Mr. Benson and I—did not put an arbitrary price on the options. We used the BSM formula, which is used by virtually everyone. I have always thought that it was considered to be an unbiased and accurate way of valuing options.

Jennifer Smith: My second major question last night to John was: “What is this BSM formula, and how is it coming up with an option price that seems so out of whack with my instincts?” Its precision alone was unnerving. Any formula that says an option should be worth exactly $19.49 made me skeptical—or should I say, nervous. As a scientist, I knew that the BSM formula had to be based on a set of assumptions. I also knew that in the course of one evening, I had no chance of understanding all the intricacies of option pricing models; so, I took a simpler and more direct route. All I wanted to know was whether the assumptions behind the BSM formula made Helvetia’s options look more desirable or less desirable to me. It was a simple plus and minus evaluation, and at the end, I asked myself whether the difference was large enough to nullify the $50,000 advantage of Helvetia’s offer. For me, the Helvetia offer came up short; so, I accepted the Zentrum offer.

Daniel Weiss: I find it amazing that you did all this work in one evening. Now, I am doubly disappointed that you will not be working with us.

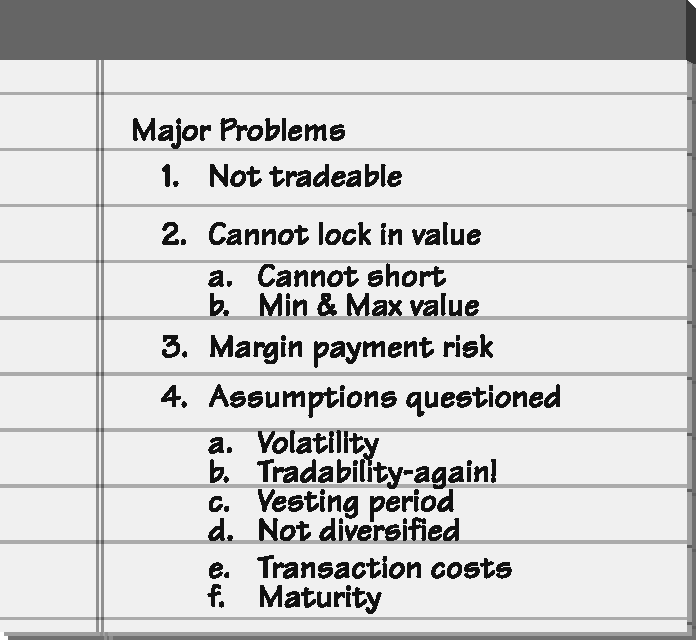

Jennifer Smith: Here’s what I discovered from John. The BSM formula was designed for tradable, short-term options rather than nontradable, nontransferable, long-term options, like Helvetia was offering me. John said that you probably based your option prices on past market statistics, plugged the six important parameters into the BSM formula, and assumed that these factors would remain constant over the maturity of my options.

Daniel Weiss: Yes. That is exactly what we did.

Jennifer Smith: Well, I figured that, with just slight modifications in your assumptions and their constancy over time, my options could be worth either far more or far less than the BSM formula estimated.

Daniel Weiss: I understand. You questioned not only the factors we entered into the formula but also their stability over time, and because of this risk, you turned down our offer.

Jennifer Smith: Exactly. I was surprised to find over the course of last evening how risk-averse I am. Do you know what else bothered me about BSM?

Daniel Weiss: Please tell me.

Jennifer Smith: The common sense, or lack of it, behind some of the assumptions used in the formula.

Daniel Weiss: The common sense? Do they have to make common sense?

Jennifer Smith: They do to me. Remember that I’m a research scientist with an analytical education but with little or no training in finance.

Daniel Weiss: Do you have an example?

Jennifer Smith: Take volatility, for instance. I now understand why volatility is important to option pricing, but we have just come out of a tumultuous economic and political period. This increased volatility raised the BSM price of the options you offered, but curiously, lowered their value to me.

Daniel Weiss: What is your prediction about the future?

Jennifer Smith: Looking forward, the financial media seem to be predicting stormier conditions —which means higher volatility. This raises my options’ BSM price but lowers their value to me. Sorry, Daniel and Tom, but I don’t see how increased volatility and uncertainty help me. For me to place a higher value on Helvetia options, I would need to believe that they would grow at a steady positive rate, so I could exercise them in three to five years at a profit. Increased volatility is a threat to me because the period of time when I would be allowed and want to exercise them might coincide with a gigantic dip in the share price. This led me into the issue of tradability.

Daniel Weiss: So, tradability, again. Are you saying that because these options are not tradable, their value is reduced to you?

Jennifer Smith: Precisely, and, for me, that’s a big negative. They’re not tradable, and they’re not transferable. In other words, only I can exercise them and when I do, I have to exercise them against Helvetia. John told me that high volatility increases the price of tradable options, but it may not increase the value of nontradable options like the kind you were offering me. BSM assumes that it’s unwise, or, more formally, “sub-optimal” for investors to exercise call options early because they could always sell them in the market for their intrinsic value and time value.

For example, suppose that today I bought a five-year call option on a Helvetia share with a $50 strike price, and then sold it three years later when the market price was $60. I’d get $10 for the amount by which the option was in-the-money—this is called the option’s intrinsic value— and I’d get additional compensation for the two years of remaining maturity—this is called the option’s time value. The Helvetia options you’re offering me can’t be sold in the market. I’d have to sell them directly to Helvetia, and then I’d receive only their intrinsic value. In other words, because they aren’t tradable or transferable, I’d earn nothing for the time remaining to maturity. Because of their lack of tradability, your offer earned another black mark in my book.

Daniel Weiss: You seem to have gone right to the critical assumptions of the BSM formula and questioned them in ways that we didn’t consider. OK, Dr. Smith, I’m beginning to see your point; so, I guess that Mr. Benson and I should go back to the drawing board and—

Jennifer Smith: Hold on! I’m not done. There are more points to take into consideration. Since I have your attention, may I continue?

Daniel Weiss: Please do.

Jennifer Smith: Your vesting period also irked me. I knew that a three-year vesting period was normal—I didn’t need John to tell me that—but the vesting period’s length was not one of the six factors that John said was used in the BSM formula. I figured that, if restrictions like this could be entered into the formula, they surely would reduce the price of my options and their value to me. They would not raise it. Look at it this way, Daniel, I could quit or be fired before the three-year vesting period ended, and, if I did quit or was fired, I’d receive nothing! Again, I put this factor in the negative column, but admittedly, I was unsure how much difference it made to my final decision.

Daniel Weiss: I’m humbled by all the work you put into this and by what you have taught me already. Is that all, or is there more?

Jennifer Smith: I’m almost done. By accepting your offer, I would have made my portfolio even more lopsided than it already is because I’d be swimming in Helvetia exposure, with little chance to diversify until I exercised the options. This increased vulnerability was another reason my valuation of the Helvetia call options may have differed from your valuation. I was also concerned that the BSM formula assumes a world in which investors pay no transaction costs and have an ability to sell short their shares—which I already mentioned could not be done. Daniel, the more I thought about your offer, the more I realized that the $50,000 premium you thought you were paying was not a premium to me.

Daniel Weiss: What would you have said if I had offered you options with the same strike price but with 10-year, rather than five-year, maturities? Mr. Benson calculated that a 10-year option should have a price of $27.84.

Jennifer Smith: Funny you should mention that. Near the end of our meal last night, John and I began to troubleshoot ways to make your deal look more attractive. We discussed lengthening the maturity of your options because the BSM formula says that the longer the maturity, the higher the option’s price.

Daniel Weiss: I guess that’s something we can all agree on!

Jennifer Smith: Not really.

Daniel Weiss: Unbelievable; that can not be true!

Jennifer Smith: Here’s why. First, if you gave me 10-year call options worth $27.84, but kept my ESO compensation at $200,000, then all you’d be doing is reducing the number of options I got from 10,262 to about 7,200. I know that you graciously rounded up my compensation to 10,500 options, but you get the point.

Daniel Weiss: Yes, I see what you mean. In that case, we might have had to make an adjustment.

Jennifer Smith: But, Daniel, that’s not my main point. My major problem with increasing the maturity of these options is it would not significantly raise their value to me because the options wouldn’t be tradable and because I couldn’t short the Helvetia shares. The change in value to you and the BSM formula from doubling the maturity would be more than $8, but to me the difference, if any, would be miniscule.

Daniel Weiss: How is that possible?

Jennifer Smith: I asked myself: “What use would it be to double the length of my options if there was no chance I was going to wait 10 years to cash them in, and no way to sell them so I could take advantage of the remaining time to maturity?” John mentioned that in general, the more risk-averse an individual is and the more significant stock options are as a portion of her portfolio, the earlier she is likely to exercise these options. He explained that most people cash in their ESOs soon after the vesting period ends, which in my case would be three years. He assumed that I’d probably do the same; so, whether you gave me a five-year option or a 10-year option, the relevant period for me would remain about three years. Doubling an option’s maturity might have its greatest appeal to someone like Methuselah, who lived to be 969 years old. If I had a well-diversified portfolio and your stock options were only a small part of my total wealth, then the uncertainty surrounding their value would be less important to me. I could afford to wait before exercising, even if the share price fell. Sorry Daniel, but even if you increased the maturity of the options, it probably wouldn’t have made much of a difference—but thank you for asking.

Daniel Weiss: Mr. Benson, you have been uncharacteristically quiet through all of this. What do you have to say about Dr. Smith’s arguments?

Tom Benson: Actually, I am a little embarrassed because I agree with all of them. Dr. Smith did an excellent job, but in my defense, I tried to answer the question you asked me, which was “What is the market price of a five-year option with a $50 exercise price.” Sorry, I should have been more alert to why you needed the option’s price. Together, we might have been able to head off many of these valuation and communication problems.

Daniel Weiss: Dr. Smith, on behalf of Mr. Benson and me, I want to thank you for your time, openness, and honesty. This conversation has been a real eye-opener for me, but it may take some time for me to digest it all.

Jennifer Smith: It was my pleasure. I’m sure I would have enjoyed working at Helvetia.

Daniel Weiss knew that he had a lot of explaining to do this afternoon when he met with Helvetia’s CEO. It was now clear to him that the valuation of stock options was not as black and white as he had thought. In the future, before he assigned a value to Helvetia’s ESOs, he would need to think harder about all the issues Dr. Smith outlined to him.

Problems with ESOs

As you can see from the discussion among Jennifer Smith, Daniel Weiss, and Tom Benson, the decision to use stock options to compensate executives could lead to difficulties. Shortcomings of the BSM formula (and other models) for pricing ESOs have long been recognized by the academic and business communities, and new valuation models are being developed that account for the idiosyncrasies of ESOs.20 In addition, companies are experimenting with solutions that address these specific problems. For example, some companies (e.g., Google) have offered their employees transferable stock options, which allow them to capture the options’ intrinsic value and time value.21 Other companies, like Swiss-based Roche Holding and Givaudan SA, have offered their employees exchange-traded options rather than ones that could be exercised only against the company.

In addition to valuation dilemmas, there are other important issues, such as: Are ESOs the best way to motivate employees? Could they motivate undesired behavior? Do ESOs really improve company performance? Is there a way they can reward employees’ performance relative to competitors rather than absolutely, relative to the company’s own share price?

Employee Motivation

To be successful, any pay-for-performance compensation plan should link a company’s success drivers to clearly defined, transparent measures that employees understand and are able to influence—but not manipulate. In other words, there must be firmly established goals that employees understand and have authority to influence but that are not open to exploitation.

Many people believe that ESOs are an ideal way to motivate employees because rewards are given only when the stock price increases, and, therefore, the company is in a position to pay extra compensation; but should options be given to all employees?,22 It is true that every employee’s actions influence the stock price, but on a practical, day-to-day level, how many people in a company believe that what they do has any direct, identifiable effect on daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly fluctuations of a share’s value?23 A better incentive for energizing employees and rewarding performance may be setting goals that are more directly under their control, such as targets for increased production, better customer service levels, less returned merchandise, or fewer customer complaints.

Critics ask: “How often do employees working in back-office jobs, maintenance crews, or cost centers reflect on how their productivity affects the share price?” Even in cases where employees may have relatively large degrees of influence on the share price (e.g., high-level executives), the multitude of co-workers with similar titles and responsibilities may make the weight of any individual’s decisions and the narrow scope of responsibilities seem small. Surely there is a paradox here because collective actions of a company’s workers have a direct and significant effect on the share price, but the actions of just one of these individuals is relatively small in most cases.

The Share Price of “Good Companies”

Another reason stock options may not be good motivators of employees is the share prices of “good companies” do not always rise above average market returns. As illogical as this statement may seem, a moment’s reflection will show that it is true. If a company is well run, has good prospects, and investors recognize this, the market should factor the quality management and bright prospects into the current share price. So long as the company meets (and does not exceed or fall short of) the market’s already high expectations, the share should earn just an average return. Only if performance is better than expected will the shares earn above-average returns.24 For employees working in companies that are the darlings of Wall Street, the prospects of bettering market expectations could be difficult, and therefore, the employees’ likelihood of profiting richly from stock option compensation could be low.

Motivating undesired behavior

ESOs could encourage shortsightedness in business decisions because they focus on the goal of increasing share prices rather than on the enabling factors that cause the share price to appreciate, such as profit margins, sales growth, cost of capital, and discounted cash flows.25 Establishing stock option plans could encourage managers to artificially inflate share prices by reducing dividend payouts, using cash funds to repurchase outstanding shares, or borrowing to finance the repurchase of shares—thereby increasing the company’s leverage and level of risk.26 Furthermore, because the market value of options increases with volatility, there is reason to wonder if granting them provides incentives for managers to imprudently amplify the operating risks and non-operating risks of their companies. Some industry analysts believe that financial misconduct at companies like Enron and WorldCom, where executives seemed narrowly focused on raising the short-term value of their option compensation, was at least part of the motivation for Microsoft and other companies to change their incentive programs away from ESOs.27

An example of undesirable behavior is illegally backdating ESOs. Backdating occurs when a company grants ESOs on one date (e.g., June 1) and then changes the issue date afterwards (e.g., to March 1) so the options have greater value. Backdating options is legal, as long as it is reported promptly. What is illegal is forging, falsifying, hiding, or not reporting material option expenses. Backdating carries special cachet in the current debate because it connects financial transparency with issues related to fair executive compensation and equitable tax burdens.28

Improving Performance

Fundamental to the question “Why ESOs?” is a current debate about whether stock option compensation actually improves companies’ performance. Critics ask if there is any evidence showing that companies using stock option plans perform better than companies that do not. The United States has had more than two decades of intensive experience using this form of compensation. As a result, there is a wealth of information available for evaluating the effects of stock options on corporate performance. Unfortunately, the results are ambiguous, which means the ultimate verdict is still to be determined.29

Absolute Versus Relative Performance

Another potential problem with stock options is the absolute, rather than relative, nature of their payoffs. A rising tide tends to raise all ships, even those carrying a lot of excess baggage and lacking direction. In rising markets, stock options reward employees even if their performance is worse than that of competitors. In falling markets, these options provide no compensation, even if the company’s performance is stellar relative to competitors. This asymmetry and lack of relative comparison introduces an element of uncertainty and unfairness into employees’ compensation because it decouples compensation from personal performance and makes compensation dependent on the broader macroeconomic environment. Because of this asymmetry, in falling markets stock options give employees with specialized training an incentive to switch employers to get new stock options with better upside potential.

Possible Solutions to Employee Stock Option Problems

Some innovative compensation plans that address the shortcomings of “plain vanilla” ESOs have been proposed and implemented. Following are the major ones.

Premium-Priced Stock Options

Business acumen is often confused with being in the right place at the right time. Plain, at-the-money stock options reward employees whenever the share price increases, even if the appreciation is less than the average competitor’s increase and even if it is due entirely to general market trends (i.e., not because of effective management or superior strategy). One way to level the playing field is by offering premium-priced stock options, which have strike prices anywhere from 25 percent to 100 percent out-of-the-money. To gain intrinsic value, the share price must rise above the premium strike price; so, this option offers a way for companies to raise the performance hurdle for their employees. Suppose a company had a share price of $40, and it offered five-year ESOs with a premium strike price of 50 percent. To be in-the-money, the company’s share price would have to increase to more than $60 ($40 plus a 50 percent premium).

The benefit of premium-priced stock option plans is they are relatively transparent (employees understand them, but not as well as plain, at-the-money options), and they tie payment to a targeted performance level. In other words, they decouple compensation from undistinguished performance and from lucky upticks in a company’s share price.

One problem with premium-priced option plans is their potential to dilute shareholder earnings and shareholder control more severely than plain, at-the-money call option plans. Raising the payoff bar makes each call option less valuable; so, companies using them should expect to compensate each employee with a larger number of options for any defined level of compensation. If the options are exercised in the future and the company issues new shares to meet the demand, dilution of ownership and dilution of earnings could result.

Premium-priced option plans help to solve the “free rider” problem that occurs when there is any positive change in share price, but they do nothing to reward employees who have superior performance in down markets. For a solution to this problem, consider index options.

Index Options

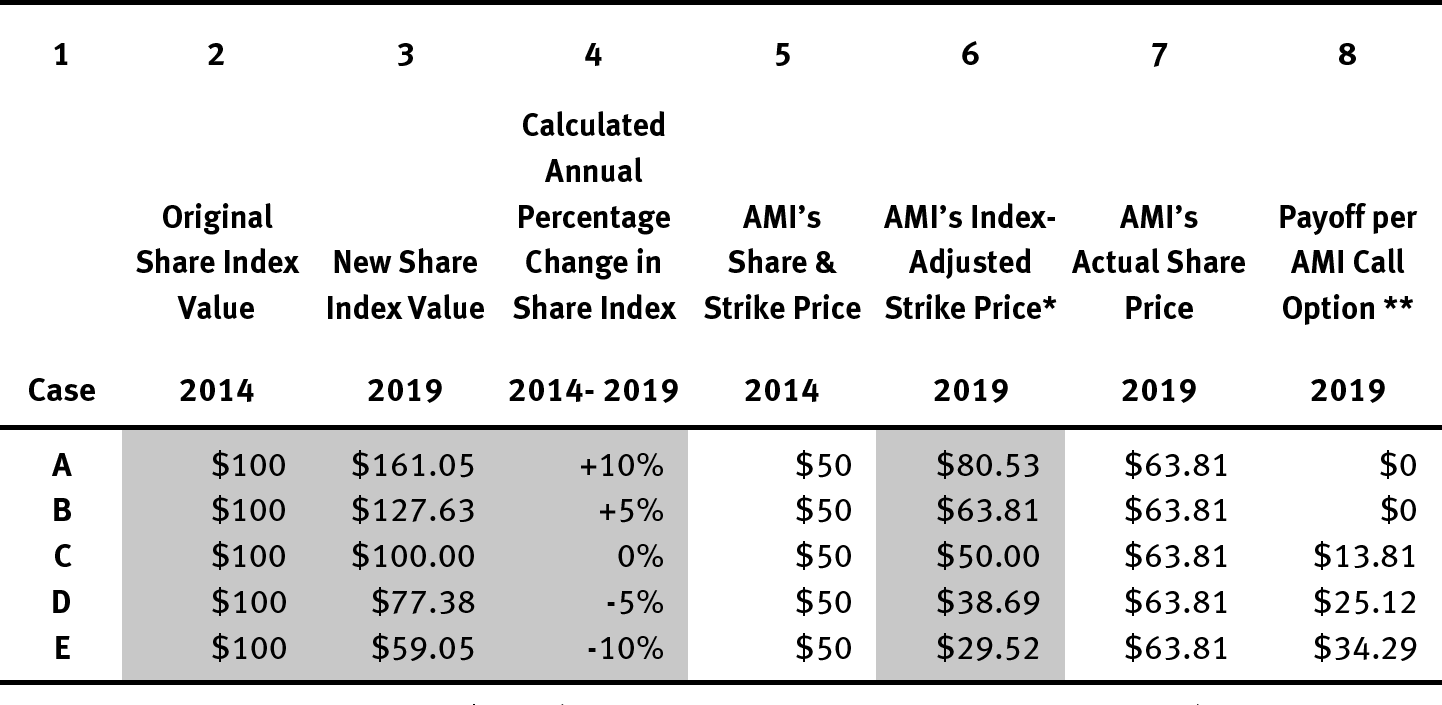

Index option plans offer ways to even-handedly reward employees for above average company performance in both up markets and down markets because this type of compensation ties the exercise price to a peer index.30 To see how such a plan works, suppose that, in 2014, Aztec Microchip, Inc. (AMI) devised an index option plan offering five-year, at-the-money stock options that had a positive payout only when AMI’s share price outperformed its four leading competitors. To ensure this result, the strike price on the AMI options was adjusted at maturity by the percentage growth or decline in the index.

Suppose that, at the end of 2014, AMI’s share price was $50, and it appreciated during the next five years by a compound annual rate of 5 percent to $63.81. In 2014, AMI’s four major competitors had share prices of $15, $20, $25, and $40, respectively. Therefore, at inception, the competitor share index against which AMI would compare its performance equaled $100.31

Table 2.1, Case A, considers how much an AMI employee would receive if the competitor share index rose from $100 in 2014 (Column 2) to $161.05 in 2019 (Column 3) —five years later.32 The change from $100 to $161.05 is a compound annual growth rate of 10 percent (see Column 4).33 Therefore, AMI’s strike price in 2019 would automatically change to reflect the index. Because AMI’s share strike price started at $50 (Column 5), a 10 percent annual increase over five years implies it should be $80.53 (Column 6), to stay even with the index. AMI’s actual share price rose at a compound annual rate of 5 percent to equal $63.81 (Column 7) in 2019. Because AMI’s share price rose only by 5 percent to $63.81 (Column 7) and the index-adjusted strike price equals $80.53 (Column 6), the options would expire out-of-the-money, and employees would earn nothing (Column 8).

Table 2.1: Example of Index Call Option Plan for Aztec Microchip Inc. (AMI)

* AMI’s strike price in 2019 = $50 x (1 + annual percentage change of index price)5.

** Payoff per AMI call option = Greater of $0 or (Market price in 2019 – Strike price)

In Case B, the payoff would be also zero because the options’ strike price rose by the same compound annual rate as the index. Therefore, AMI’s options would be at-the-money. In Case C, AMI’s options would be in-the-money because its average annual performance (5 percent) was greater than the Index (zero percent). As a result, the strike price on AMI’s options would remain at $50, and the option payoff would be $13.81, which is the difference between the market price of an AMI share and the index-adjusted strike price of the option ($63.81 – $50 = $13.81). In Cases D and E, the payoffs are also positive. A falling market causes the strike price to fall at the same compound annual rate as the index and, thereby, increases the payoff on AMI’s options.

All the cases in Table 2.1 deal with payoffs assuming that the AMI share price rose by 5 percent. Even if AMI’s share price fell over the option’s five-year maturity, so long as the percentage decline was lower than the drop in the index, there would be a positive option payoff because the strike price of AMI options would be lower than the market price of its shares.

The use of relative, performance-based incentives makes compensation symmetric regardless of the general share price movement of the market. In this way, index option plans reduce the variance of employee compensation, better tie rewards to performance, and, therefore, increase fairness. For these reasons, many human resource analysts feel that indexed compensation should be incorporated into the third pillar of all executive compensation programs.

Though index options offer companies many advantages, they have their share of drawbacks. One major disadvantage is their complexity. Employees cannot simply open the newspaper to the financial pages and calculate the intrinsic value of their options from the stock quotes. To do that, they need to compute how their companies fared relative to the index. The complexity could lead to waning enthusiasm for this incentive-based compensation plan and diminishing performance. Companies might combat this potential glitch by creating links on their websites with information on option values, which are updated daily.

Another problem with index options is their potential to more severely dilute company earnings and control than plain vanilla stock options. Like premium options, index options are not worth as much as regular (plain vanilla) options because they reward relative performance and not absolute performance. Therefore, companies should expect to pay their employees more of them for any defined level of compensation.34 As a consequence, if all the extra options were exercised and the company met this increased demand by issuing new shares rather than hedging with derivatives or buying back its shares in the open market, dilution of shareholder earnings and control could result.35 Before adopting an index option plan, companies should be fully aware of the incentives they create. Index options have lower risks than traditional options because they (can) reward employees in up and down markets; but there is much more to consider. For instance, research shows that if they are not too far out-of-the-money, index options are more sensitive to changes in the underlying’s price and to changes in volatility than are traditional options.36 Therefore, they provide managers with greater incentives to increase risks.

Regarding the effects of volatility, it should be kept in mind that the value of an index option is influenced by idiosyncratic firm-specific risks rather than overall market or industry risks. Filtering out the portion of overall volatility that is common to all firms in an industry increases an index option’s sensitivity to risk.37 As a result, managers may have greater incentives to increase their firms’ idiosyncratic risks and to pursue activities that reduce the correlation between their firms’ performance and the performance of the index. These decisions could change the nature of a company’s business and affect important managerial decisions, such as whether and how to diversify or hedge. Therefore, firms instituting index option plans should closely monitor them and consider installing risk brakes to ensure that operations remain within reasonable bounds.

Index option plans are not panaceas for all the shortcomings of plain-vanilla, option-based compensation plans. Their adoption most certainly would introduce new problems, such as determining the appropriate index to use (e.g., a market index or an industry index) and the date on which to lock in the compensation terms. Nevertheless, index options are worth considering because they remedy one of the major shortcomings of traditional ESOs: They reward managers for factors under their control and do not penalize them for factors out of their control.

Restricted Shares

Restricted shares offer employees compensation in the form of rights to receive shares. Unlike stock options, which gain value only if a company’s share price rises above the strike price, restricted shares are actual payments in shares, which maintain value (albeit less) even if the share price falls. They could have the added benefit of placing greater emphasis on financial performance over longer periods.

Typically, restricted shares have vesting periods ranging from one to ten years, but employees receiving them are entitled to full dividend and voting rights. The major limitations facing employees who receive restricted shares are related to transfer and selling rights. Accounting treatment can vary, but in the United States, companies recognize the costs of restricted shares as compensation expenses that are prorated over the vesting period. In addition, employees must report unrestricted share compensation as taxable income.

Omnibus Plans

Omnibus plans set out a common list of possible compensation alternatives and leave it to the compensation committees or the management teams in individual countries to craft agreements that tailor compensation to the preferences, rules, laws, practices, and expectations of the local workforces.38 Omnibus plans allow for the granting of many different types of awards, ranging from conventional options, to stock appreciation rights, to restricted stock plans and various types of performance-based awards. These plans make sense for companies designing equity-based compensation systems for operations in multiple geographic areas. By offering a common palette from which to choose, companies can promote and preserve shared corporate goals.

Conclusion

Many companies have embraced ESOs because they are flexible, encourage workers to increase shareholder value, provide a noncash way to hire and retain quality employees, align cash payments with a company’s ability to pay, and provide cash-flow incentives. Employees have also welcomed ESOs because of their benevolent tax treatment and because options limit downside risks and offer the potential to make employees fabulously rich.

Because of the distinctive characteristics of ESOs, the formulas and models that are normally used to value exchange-traded options (e.g., BSM formula, binominal lattice model, and Monte Carlo model) may be inadequate, but help is on the way. New and innovative methodologies are being developed to account for factors, such vesting periods, relevant maturities, and the lack of transferability and tradability.

Stock option compensation plans tend to be most effective when employees are fully involved in their creation and when the workforce is cognizant of their benefits, costs, and risks. For stock options to align incentives properly, employees must understand the cause-and-effect relationship between what they do and how they affect their companies’ share prices. If employee stock option plans are implemented to align employee incentives with those of the public shareholders, companies should be open about this goal and conscious of how hard it is to achieve.

Review Questions

- Explain the reasoning behind ESOs as a source of compensation. What do ESOs accomplish that salary and bonus adjustments don’t accomplish? Who in a company should receive ESOs?

- Develop a brief presentation for the head of your company’s human resource department on the advantages and disadvantages of compensating a CEO with at-the-money stock options.

- Explain why employees may value ESOs lower than their employers.

- Explain premium-priced stock options. What are their advantages and disadvantages in terms of aligning employee interests with shareholder value?

- Explain index options. What are their advantages and disadvantages in terms of aligning employee interests with shareholder value? What index should be used?

- What would you expect to happen to corporate dividends (i.e., rise, fall, or stay the same) for companies that introduce stock option plans? Explain.

- What would you expect to happen to the size and number of stock buy-backs at companies that introduce employee stock option plans? Explain.

- Using the figures in the table below and the BSM model, a call option should be priced at $16.25. Based on this information, answer the following questions:

| Option Pricing Information | |

| Share price | $50 |

| Strike price | $50 |

| Time to Expiration (Maturity) | 5 Years |

| Volatility | 25% |

| Risk- free interest rate | 5.00% |

| Dividends | $0 |

a.Suppose you were offered $100,000 of stock option compensation. If the options were valued at their market price:

i.How many options would you get?

ii.Explain how you could lock in, immediately, the minimum value of these options?

iii.After three years, if the stock price rises by 10 percent, the ESO price falls from $16.25 to $12.94. How is this possible? If you exercised this option, how much would you receive?

b.Suppose that in five years (i.e., at maturity) the share price rose to $130. If you exercised your options:

i.How much, if anything, will you have to pay if you wanted to own the shares?

ii.How much, if anything, will you receive if you cashed out?

iii.How, if at all, would your answers to Question 8b(ii) change if the share price rose to $130 in three years, and you exercised your options (i.e., exercised them in three years rather than five years)?

Bibliography

Aggarwal, R. and Samwick, A. “The Other Side of the Trade-off: The Impact of Risk on Executive Compensation.” Journal of Political Economy 107 (1999), 65–105.

Aldatmaz, Serdar, Ouimet, Paige, and Van Wesep, Edward, D. “The Option to Quit: The Effect of ESO on Turnover.” Journal of Financial Economics 127(1), (January 2018), 136 – 151.

Anonymous. “The Trouble with Stock Options.” The Economist Magazine (August 7, 1999), 13–14.

Bebchuk, Lucian and Fried, Jesse. Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Bergstresser, Daniel and Philippon, Thomas. “CEO Incentives and Earnings Management.” Journal of Financial Economics, 80 (2006), 511–529.

Berle, Adolph A. and Means, Gardner C. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: Macmillan, 1932.

Bettis, J.C., Bizjak, J.M., and Lemmon, M.L. “Exercise Behavior, Valuation, and the Incentive Effects of ESO.” Journal of Financial Economics 76(2) (May 2005), 445–470.

Black, Fischer and Scholes, Myron. “The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities.” Journal of Political Economy 27 (1973), 637–654.

Brenner, M., Sundaram, R., and Yermack, D. “Altering the Terms of Executive Stock Options.” Journal of Financial Economics 57 (2000), 103–128.

Brickly, S. Bhagat and Lease, R. “The Impact of Long-Range Managerial Compensation Plans on Shareholder Wealth.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 7(1–3) (1985), 115–129.

Buffett, Warren. “Stock Options and Common Sense.” The Washington Post (April 9, 2002), A19.

Bulan, L., Sanyal, P., and Yan, Z. “A Few Bad Apples: An Analysis of CEO Performance Pay and Firm Productivity,” Journal of Economics and Business, 62(4) (2010), 273-306

Calvet, A. Louis and Rahman, Abdul H. “The Subjective Valuation of Indexed Stock Options and Their Incentive Effects.” The Financial Review 41(2) (May 2006), 205–227.

Carpenter, J., “The Exercise and Valuation of Executive Stock Options.” Journal of Financial Economics 96 (1998), 453–473.

Charny, Ben. “UPDATE: Google To Let Employees Trade Their Stock Options to Institutions.” Dow Jones Business News (December 12, 2006).

Chen, Y. R. and Lee, B. S. “A Dynamic Analysis of Executive Stock Options: Determinants and Consequences.” Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(1), 88–103.

Conyon, M. and Sadler G. “CEO Compensation, Option Incentives and Information Disclosure.” Review of Financial Economics 10 (2002), 251–277.

Core, J. E. and Guay, W. R. “Stock Option Plans for Non-executive Employees.” Journal of Financial Economics, 61(2) (2001), 253–287.

Cui, H. and Mak, Y. T. (2002). “The Relationship between Managerial Ownership and Firm Performance in High R&D Firms.” Journal of Corporate Finance, 8(4), 313–336.

Demsetz, Harold. “The Structure of Ownership and the Theory of the Firm.” Journal of Law and Economics 26 (1983), 375–390.

Fama, Eugene F. “Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm.” Journal of Political Economy 88 (1980), 288–307.

Fama, Eugene F. and Jensen, Michael C. “Separation of Ownership and Control.” Journal of Law and Economics 26 (1983), 301–325.

Fenn, George W. and Liang, Nellie. “Corporate Payout Policy and Managerial Stock Incentives.” Journal of Financial Economics 60 (1) (April 2001), 45–72.

Folami, L.B., Arora, T., and Alli, K.L. “Using Lattice Models to Value ESO under SFAS 123(R).” CPA Journal 76(9) (September 2006), 38–43.

Frye, M. B. “Equity-based Compensation for Employees: Firm Performance and Determinants.” The Journal of Financial Research, 27 (2004), 31–54.

Garen, J. “Executive Compensation and Principal-Agent Theory.” Journal of Political Economy 102 (1994), 1175–1199.

Gibbons, R. “Incentives in Organizations.” Journal of Economics Perspective 12 (1998), 115–132.

Greene, Thomas M. and Bianchi, Alden J. “Mixing Oil and Water: Backdated Stock Options under IRC Section 409A.” Benefits Law Journal 20(2) (Summer 2007), 45–50.

Grossman, Sanford J. and Hart, Oliver D. “An Analysis of the Principal-Agent Problem.” Econometrica 51 (1983), 7–46.

Hall, B.J. and Murphy, K.J. “Stock Options for Undiversified Executives.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 33 (2002), 3–42.

Hall, B.J. and Murphy, K.J. “Optimal Exercise Prices for Executive Stock Options.” American Economic Review 90(2) (May 2000), 209–214.

Hart, Oliver D. “The Market Mechanism as an Incentive Scheme.” Bell Journal of Economics 14 (1983), 366–382.

Himmelberg, C., Hubbard, G., and Palia, D. “Understanding the Determinants of Managerial Ownership and the Link Between Ownership and Performance.” Journal of Financial Economics 53 (1999), 353–384.

Holmström, Bengt. “Managerial Incentive Problems: A Dynamic Perspective.” Review of Economics Studies 66 (1999), 169–182.

Holmström, Bengt. “Moral Hazard and Observability.” The Bell Journal of Economics 10 (1979), 74–91.

Hutchinson, Marion and Gull, Ferdinand A. “The Effects of Executive Share Options and Investment Opportunities on Firms’ Accounting Performance: Some Australian Evidence.” The British Accounting Review 38(3) (September 2006), 277–297.

Jenkins, Holman W. Jr. “The Backdating Molehill.” The Wall Street Journal (March 7, 2007), A16.

Jensen, Michael and Murphy, Kevin. “CEO Incentives—It’s Not How Much You Pay, but How.” Harvard Business Review 68(3) (May/June 1990), 138–149.

Jensen, Michael C. and Ruback, Richard S. “The Market for Corporate Control: The Scientific Evidence.” Journal of Financial Economics 11 (1983), 5–50.

Jensen, Michel C. and Meckling, William H. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure.” Journal of Financial Economics 3 (1976), 305–360.

Jin, Li. “CEO Compensation, Diversification, and Incentives.” Journal of Financial Economics 66(1) (October 2002), 1–46.

Johnson, Shane A. and Tian, Yisong S. “Indexed Executive Stock Options.” Journal of Financial Economics (July 2000), 35–64.

Kahl, M., Liu, J. and Longstaff, F. “Paper Millionaires: How Valuable Is Stock to a Shareholder Who Is Restricted from Selling It?” Journal of Financial Economics 67 (2003), 385–410.

Kalra, Neha and Bagga Rajesh. “A Review of Employee Stock Option Plans: Panacea or Pandora’s Box for Firm Performance.” International Journal of Management Excellence 10(1) (December 2017), 1201–1207.

Kocieniewski, David, “Tax Benefits from Options as Windfall for Businesses.” The New York Times, December 29, 2011.

Koller, T., Goedhart, M., and Wessels, D. Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, 4th ed. New York: Wiley, June 2005.

Kulatilaka, Nalin and Marcus, Alan J. “Valuing ESO.” Financial Analysts Journal (November–December 1994), 46–56.

Kwon, See Sung S. and Yin, Qin Jennifer. “Executive Compensation, Investment Opportunities, and Earnings Management: High-Tech Firms Versus Low-Tech Firms.” Journal of Accounting 21(2) (Spring 2006), 119–148.

Lam, Swee-Sum Lam and Chng, Bey-Fen. “Do Executive Stock Option Grants Have Value Implications for Firm Performance?” Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 26(3) (May 2006), 249–274.

Lambert, Richard A., Lanen, William N., and Larcker, David F. “Executive Stock Options Plans and Corporate Dividend Policy.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 24(4) (December 1989), 409–425.

Leahey, Anne L. and Zimmermann, Raymond A. “A Road Map for Share-Based Compensation.” Journal of Accountancy. 203(4) (April 2007), 50–54.

Lewellen, W.G., Park, T., and Ro B.T., “Self-Serving Behavior in Managers’ Discretionary Information Disclosure.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 21 (1996), 227–251.

Merton, Robert C. “Theory of Rational Option Pricing.” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 4 (1973), 141–183.

Milbourn, T. T., “CEO Reputation and Stock-Based Compensation.” Journal of Financial Economics 68(2) (May 2003), 233–262.

Mirrlees, James A. “The Optimal Structure of Incentives and Authority within an Organization.” Bell Journal of Economics 7 (1976), 105–131.

Morck, Randall, Shliefer, Andrei, and Vishny, Robert W. “Management Ownership and Market Valuation: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Financial Economics 20 (1988), 293–315.

Muelbrock, L. “The Efficiency of Equity-Linked Compensation: Understanding the Full Cost of Awarding Executive Stock Options.” Financial Management 30 (2001), 5–30.

Murphy, Kevin J. “Executive Compensation,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_ id=163914 (April 1998, posted to database: 19 May 1999), 29. Accessed on January 15, 2018.

National Center for Employee Ownership. National Employee Ownership and Corporate Performance (ESOPs, etc.) and Corporate Performance. NCEO Library, http://www.nceo.org/library/corpperf.html. Accessed on January 15, 2018.

National Center for Employee Ownership. The Stock Options Book. 18th ed. Oakland, CA: National Center for Employee Ownership, February 2007. https://www.nceo.org/articles/research-employee-ownership-corporate-performance. Accessed on January 15, 2018.

Norris, Floyd. “What Seller Wants a Low Price?” The New York Times (June 1, 2007), C1.

Ofek, E. and Yermack, D. “Taking Stock: Equity-Based Compensation and the Evolution of Managerial Ownership.” Journal of Finance 55 (2000), 1367–1384.

Perry, Tod and Zenner, Marc. “Pay for Performance? Government Regulation and the Structure of Compensation.” Journal of Financial Economics 62(3), December 2001, 453–488.

Pfeffer, Jeffrey. “Six Dangerous Myths about Pay.” Harvard Business Review. Reprint number 98309 (May–June 1998).

Rappaport, A., Kohn, A.K, Zehnder, E., and Pfeffer, J. Harvard Business Review on Compensation. Cambridge: Harvard Press Book, November 1, 2001.

Rogerson, William. “The First-Order Approach to Principal Agent-Problems.” Econometrica 53 (1985), 1357–1367.

Rosen, C., Case, J., and Staubus, M. “Every Employee an Owner. [Really].” Harvard Business Review 83(6) (June 2005), 122–130.

Ross, Stephen A. “The Economic Theory of Agency: The Principal’s Problem.” American Economic Review 63 (1973), 134–139.

Schulz, Eric and Tubbs, Stewart L. “Stock Options Influence on Manager’s Salaries and Firm Performance.” The Business Review 5(1) (September 2006), 14–19.

Sesil, J.C., Kroumova, M.K., Blasi, J.R., and Kruse, D.L. “Broad-Based ESO in U.S. ‘New Economy’ Firms,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 40(2) (June 2002), 273–294.

Sickles, Mark W. “Managing the Workforce to Assure Shareholder Value.” HR Focus 76 (8) (August 1999), 1, 14, 15.

Smith, Clifford W., Jr. and Watts, Ross L. “The Investment Opportunity Set and Corporate Financing, Dividend, and Compensation Policies.” Journal of Financial Economics 32 (1992), 263–292.

Thomas, Kaye A. Consider Your Options: Get the Most from Your Equity Compensation. Lisle, IL: Fairmark Press, 2007.

Yermack, D. “Good Timing: CEO Stock Option Awards and Company News Announcements.” Journal of Finance 52(2) (1997), 449–476.