Chapter 9

Société Générale and Rogue Trader Jérôme Kerviel

In 2008, Société Générale lost €4.9 billion ($7.2 billion) from excessive, one-sided positions taken by Jérôme Kerviel (JK), a junior trader working at the bank’s Paris-based Delta One unit. Of these losses, 100 percent occurred in just two-and-a-half weeks during January, with 70 percent during the last three days. Explaining how he lost so much in such a short period of time is relatively easy. But placing blame is a bit like writing a short story and allowing readers to choose their own endings. Was JK a brave derivatives trader whose actions exposed the underside of a corporate culture that treats illicitly earned profits with mild reprimands and gentle slaps on the wrist but equally dishonest losses with heavy-handed legal consequences? Or was this a story about a world-class bank with a not-so-world-class risk management system that was exploited by a single, unscrupulous rogue trader?

Société Générale (SocGen)

Société Générale (SocGen) is a French-domiciled bank founded in 1864 by decree of Napoléon III, and grew to be one of the largest and most prized financial institutions in Europe—especially for its equity trading desks. Significant acquisitions and internal growth via reinvested earnings gave the bank a strong international presence in a variety of financial sectors. During the twentieth century, SocGen survived World War I and the Great Depression, but in 1945, at the end of World War II, it was nationalized by Charles de Gaulle and stayed that way until 1987, during Jacque Chirac’s administration. Two keys to SocGen’s success were strong global economic growth—especially in Europe and the United States—and financial deregulation. The bank was also helped by its strategic decision to focus on information technology (IT), which dovetailed nicely with the growing sophistication and complexity of world financial markets.

Jérôme Kerviel (JK)

JK was a French citizen, with middle-class roots but high aspirations. Though well-educated, he failed to pass the entry examination for France’s elite universities (Grandes Écoles), such as École Polytechnique, École des Mines, or École Nationale d’Administration. Instead, JK received his undergraduate Baccalaureate degree in economics from Université de Nantes and Masters in Finance degree from the Université Lumière Lyon 2, both academically solid schools but not at the top of France’s pecking order.

In June 2000, JK began working in SocGen’s middle-office as a member of its compliance department (called The Mine). In 2005, he was promoted to the front-office, working as assistant trader for SocGen’s Delta One unit, part of the bank’s Corporate and Investment Banking division.314 As an assistant trader, his daily limit was low, but it would grow as he gained experience.

Back, Middle, and Front Office Jobs at SocGen

SocGen’s front office staff was mainly composed of graduates from elite French universities, while its back office and middle office staff graduated mainly from lower-ranked universities. Front office jobs, such as traders, have direct contact with customers and offer relatively high salaries with the potential to earn large bonuses. Back office and middle office jobs are essential to any well-functioning bank but are routine, cost-center positions focused on efficiency and security rather than top line growth. Middle office employees monitor and control bank risks. For example, they track traders’ positions, limits, profits, and losses and put management systems in place to monitor, track, aggregate, and isolate solvency, profitability, and liquidity risks. By comparison, back office staff are responsible for verifying, settling, and delivering traded securities and derivatives, as well as properly recording these transactions. They also ensure that margins are posted, marked to market, and processes are up-to-date with regulatory standards.

When JK was a member of SocGen’s compliance department, he gained an understanding of the bank’s middle office and back office computer systems, policies, rules, procedures, record keeping, product modeling, and process automation. He used this knowledge later in a front office job to navigate the pathways connecting SocGen’s front, middle, and back office systems, in order to exploit their weaknesses and avoid detection. In 2007, JK amassed a €30 billion position, followed by a €50 billion one in 2008, even though the daily trading limit for his entire team was only €125 million. Understanding how he did this is a lesson in financial deception.

Arbitraging Turbo Warrants

In 2007, SocGen promoted JK to its Delta One Listed Products (DLP) desk, as part of an eight-member team (seven traders and a supervisor). JK’s new role focused on two areas.

–Conducting customer business, mainly involving purchases and sales of plain vanilla stock-index futures contracts

–Arbitraging turbo warrants for SocGen’s proprietary account

JK’s job should have been among the lowest risk positions in SocGen’s front office, which is why his losses of €4.9 billion in January 2008 were astonishing. Due to the size of JK’s losses, a look more deeply into arbitrage, in general, and JK’s turbo arbitraging activities, in particular, is instructive.

Arbitrage is the art of finding and profiting from mispriced assets. If they are underpriced, the arbitrager buys the assets at low prices and simultaneously sells them or agrees to sell them later at higher prices. If they are over-priced, the arbitrager borrows and sells the assets at high prices and simultaneously buys them or agrees to buy them later at lower prices. Arbitrage risks are supposed to be zero, but in the trading world, they are often extremely low but not necessarily zero.

What Are Plain Calls and Puts?

Three important attributes of any option are its strike price, expiration date, and premium. Calls give buyers the right, but not the obligation, to purchase an underlying at a pre-defined price (i.e., strike price), either at or before expiration. Puts give buyers the right, but not the obligation, to sell an underlying at a pre-defined price (i.e., strike price), either at or before expiration. The option’s premium is the price a buyer pays for this right, and expiration is the date when the option becomes worthless.

At the beginning of January 2008, the DAX index’s spot price was approximately €8,000. A three-month call on the DAX index with a strike price of €8,000 gave buyers the right to purchase the DAX index at €8,000 during the next three months.315 Buyers would exercise this option only if the spot price was above €8,000. If not, the option would expire worthless. A three-month put on the DAX index with a strike price of €8,000 gave buyers the right to sell the DAX index at €8,000 during the next three months. Buyers would exercise this option only if the spot price was below €8,000. If not, the option would expire worthless.

In these examples, the spot and strike prices were same, which means the options had no intrinsic value. Nevertheless, they still had time value because there were three months remaining until expiration. During that time, if the DAX rose above €8,000, the call owner would exercise. If the DAX index fell below €8,000, the put owner would exercise.

What Are Turbo Warrants?

A turbo warrant is different from a call or put because it expires worthless if the underlying’s price breaches a fixed knockout or barrier price. Because turbo warrants expose buyers to risks not present in plain vanilla calls and puts, their premiums are lower.

A long turbo warrant is a call with a barrier price. Often the barrier is the same as the strike price. If the underlying’s price falls below the barrier, the call expires worthless. For this reason, long turbo warrants are often referred to as calls down-and-out. Because long turbos are cheaper than normal calls, they allow investors to bet on rising stock prices using greater leverage.

A short turbo is a put with a barrier price. Like a long turbo warrant, the barrier on a short turbo is usually the same as the strike price. If the underlying’s price rises above the barrier, the put expires worthless. For this reason, short turbo warrants are often referred to as puts up-and-out. Because short turbos are cheaper than normal puts, they allow investors to bet on falling prices using greater leverage.

A normal call can be exercised if the underlying’s price is above the strike price, and a normal put can be exercised if the underlying’s price is below the strike price. Long turbo warrants expire (lose all value) if the underlying’s price falls below the barrier, even if it rises later and ends above the strike price. Similarly, short turbo warrants expire worthless if the underlying’s price rises above the barrier, even if it falls later and ends below the strike price. For this reason, the values of both long and short turbo warrants are called path-dependent.

The underlying for a turbo warrant is the same as a regular option, which means it could be a share, basket of shares, index, bond, currency, or exchange-traded fund. The maturities of these derivatives, as well as the relationship between their strike and barrier prices, are negotiable. The strike and barrier prices are usually the same, and many of these options are deeply in-the-money.

Primer: Hedging Purchases and Sales of Turbo Warrants to Customers

DLP was a market maker for customers (mainly retailers and institutional investors) wishing to buy long or short turbos. Most of its client business focused on selling long turbos. Once sales were made, SocGen traders usually hedged them. Figure 9.1 shows an example using the DAX index, where the strike and barrier prices are both equal to €8,000, turbo premium equals €200, and DAX futures price is €8,050. If a DLP trader sold a long turbo warrant (i.e., sold a call down-and-out), he could hedge the position with a long DAX futures position,316 thereby transforming his short-call exposure into a synthetic short put position (see Figure 9.1A). Similarly, if the trader sold a short turbo warrant (i.e., sold a put up-and-out), the position could be hedged with short DAX futures contracts.317 As a result, the position would be transformed into a synthetic short call (see Figure 9.1B). Thereafter, these positions would be dynamically adjusted to reflect changing hedge parameters (e.g., deltas and gammas).

Primer on Arbitraging Turbo Warrants

JK’s job was to arbitrage turbo warrants for SocGen’s proprietary account by purchasing underpriced turbo warrants sold by competitors and locking in positive returns by shorting the futures index. Figure 9.2 provides an example. Suppose JK purchased a long turbo warrant with strike and barrier prices equal to €8,000 and a premium of €200 (see Figure 9.2A). To hedge this exposure, he would sell the equivalent amount of DAX futures contracts, at a price of €8,250 (see Figure 9.2B). The combination of his long call option and short futures position would transform his exposure into a long put position, with a locked in return of at least €50 (see Figure 9.2C).

At this point, two major alternatives are possible. First, if the DAX index remained above the barrier price of €8,000, the turbo warrant would remain effective and JK would earn €50. Alternatively, if the DAX index fell below the barrier, the long turbo warrant would expire, leaving JK with an uncovered short futures position (see Figure 9.2D). To lock in a gain, he would offset the short futures position with a long futures position. For instance, suppose the DAX index fell to €7,900. JK could purchase each DAX futures contract for €7,900 that he sold at initiation for €8,250, earning a net return of €350 (see Figure 9.2E). When combined with the original premium cost of €200, JK’s net gain would be €150 (i.e., €350 – €200 = €150) – see Figure 9.2F.

How JK Built His Mountainous Positions

Soon after he assumed his position at Delta One in 2005, JK began making unauthorized directional trades. Most of them were on European markets, such as the Euro Stoxx 50, German DAX, and UK FTSE 100 index exchanges. As time progressed, his exposures grew larger—rising from hundred thousands of euros to millions and billions of euros. The entire DLP unit had a daily trading limit of only €125,000, which made his €30 billion and €50 billion exposures in 2007 and 2008, respectively, grotesquely large, with dimensions beyond any reasonable bounds of ethical and responsible behavior.

2005

Success breeds excess, and JK’s early trades prove this aphorism. In July 2005, he made a directional bet on the shares of Allianz AG, a German insurance company. To profit from his expectations, he took a short €10 million forward position. On July 7, 2005, suicide attacks by organized terrorists on the London Underground and a double-decker bus killed fifty-two and injured 700 others. This tragedy caused Allianz’s share price to fall, earning JK a €500,000 return. Emboldened, he took other single-stock positions in companies such as Continental, Q-Cells, and Solarword. Between June 2005 and February 2006, JK’s fraudulent directional equity positions rose from €15 million to €135 million.318

2006

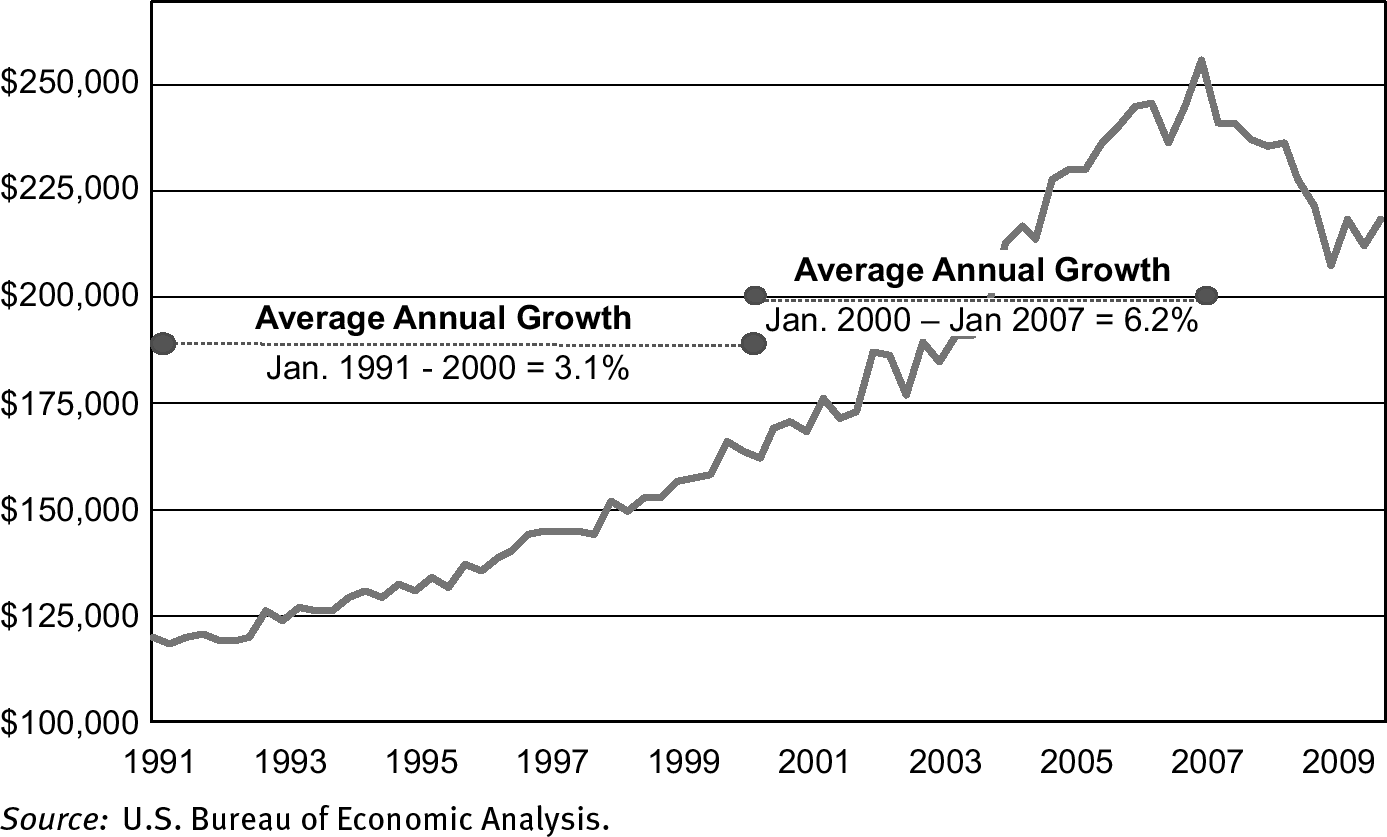

By August 2006, JK’s directional single-stock bets had reached €140 million,319 but he began shifting his trading interests to stock indices. At the time, the United States was struggling with growing subprime loans and a housing market bubble. Figure 9.3 shows that, between 1990 and 2000, the median U.S. housing price rose by 3.1 percent per year, but from the beginning of 2000 to the end of 2006 yearly appreciation doubled to 6.2 percent, becoming disconnected from its historic trend. During the second quarter of 2004, the Federal Reserve began to increase interest rates, in an effort to slow the growth of U.S. housing prices. In 2006, housing prices leveled off and fears grew that large numbers of subprime mortgage borrowers might default on their loans. JK predicted that U.S. problems would spread to Europe and took short positions on European stock market indices.

European markets remained strong through most of 2006 (see Figure 9.4). JK’s prediction proved to be incorrect, but his short positions were relatively small and, as a result, so were his losses on these speculative positions.

2007

In 2007, JK made a bold attempt to increase his trading profits. Between January 2007 and July 19, 2007, he increased the notional value of his short positions by more than 3,400 percent, from €850 million to €30 billion.320 At first, European equity markets did not cooperate. By mid-July, his short positions had accumulated losses of €2.5 billion (see Figure 9.5), but these markets fell dramatically in July and August (see Figure 9.4), allowing JK to unwind his positions, recover all of his losses, and begin earning profits (see Figure 9.5).

From a near-zero base at the beginning of September 2007, JK rebuilt his short positions to €30 billion by the end of October. Then, between November 7 and December 31, he unwound these newly created positions and ended the year with accumulated returns of €1.4 billion (see Figure 9.5).

JK’s earnings were both good and bad news. On the positive side, he had earned €1.4 billion rather than losing €2.5 billion, as he would have done in mid-July. On the negative side, there were three problems. First, arbitrage traders are not supposed to earn €1.4 billion; second, their returns are not supposed to vary by almost €4 billion during a five-month period; and third, an arbitrager should not end up earning 59 percent of DLP’s and 27 percent of Delta One’s total returns.321 In a stable of 143 proprietary traders at SocGen during 2007, JK was the fifteenth most profitable.322

To avoid reprimands and possible job termination for his unauthorized trades, JK decided to hide his 2007 gains by entering into eight fictitious forward transactions amounting to €30 billion. These fictional trades created illusionary losses of €1,345 million. When combined with his actual earnings of €1,400 million, JK reported to SocGen a handsome yearly gain of €55 million.323 For this performance, he asked for a €600,000 bonus, but due to his relatively short tenure at DLP, his supervisor offered €300,000.324

2008

Because he unwound virtually all of his short (stock index) futures positions at the end of 2007, JK began 2008 with a fresh start (i.e., no fraudulent index positions). He also had a new strategy.325 Believing that the Great Recession had ended in the United States and global economic conditions would improve, he took optimistic long positions in three European equity indices. During the first eighteen days of January, JK’s directional long positions grew to approximately €50 billion ($73 billion), with €30 billion invested on the Euro Stoxx 50 index, €18 billion on the DAX index, and €2 billion on the FTSE 100 index. These positions were excessive in every sense of the word. Not only did they exceed Delta One’s trading limit inside SocGen, they also exceeded SocGen’s limits on the European exchanges and SocGen’s total market capitalization, which was approximately €34 billion (about $50 billion).

Concerns arose when SocGen’s middle office found the bank was not in compliance with the Cooke ratio, which measures the amount of regulatory capital a bank needs to back its risk-adjusted assets (i.e., part of the Basel II Accord guidelines).326 The shortage was traced to the eight forward deals worth €30 billion, which JK transacted at the end of 2007 to cover his €1.4 billion profit. The subsequent investigation led directly back to JK and unearthed a cesspool of forgeries, lies, and other forms of deception.

JK’s Fraudulent Methods

SocGen’s risk management and reporting systems were fragmented and weak, providing JK with numerous ways to evade detection. Some of these methods masked his position and risks, while others concealed his gains or losses. To pull off his puckish trades, JK committed flagrant violations of SocGen’s internal rules, French law, and basics of ethical behavior. Among the six most commonly used methods he used were:

- Gaining unauthorized access to SocGen’s computer systems

- Using contract cancellations and modifications to mask positions and risks

- Entering pairs of offsetting trades at artificial prices

- Posting intra-monthly “provisions”

- Navigating SocGen’s dysfunctional risk management system

- Exploiting supervisor turnover

Gaining Unauthorized Access to SocGen’s Computer Systems

JK gained unauthorized access to SocGen’s back office and middle office computer systems by obtaining and using colleagues’ usernames and passwords. He knew that SocGen’s IT managers meagerly enforced periodic changes in security codes and login identities. Once in SocGen’s computer systems, JK falsified accounting records, forged both signatures and e-mails (seven in all), set up false identities, and altered documents. Chances of detection were slim because SocGen’s computer systems were unable to identify when JK logged in, the path he followed, and when he logged off.

Using Contract Cancellations and Modifications to Mask Positions and Risks

After JK entered his unauthorized directional trades, he masked them by entering fake, offsetting positions with the same or approximately the same notional values and maturities. JK knew it could take days (even weeks) for SocGen’s back office to confirm, clear, and book trades, which gave him time to reverse, modify, cancel, defer, or otherwise hide his actual positions from internal control systems and personnel. Until his fictitious trades were finalized, JK had time to earn profits on his positions.

To maximize the time it took SocGen’s back office to confirm and settle his trades, JK frequently hedged his exchange-traded positions with tailor-made, over-the-counter ones, which took longer to confirm and settle and, often, were not marked to market. He also knew that trades with deferred starting dates were not processed by SocGen’s back office until shortly before their starting dates. By booking these transactions, he could extend the time interval between placing a false transaction and reversing it.

JK kept his fake positions alive by simultaneously (1) retracting them shortly before they were processed; (2) taking new positions with extended or deferred maturities; and (3) relying on the new processing time lag to create an illusion that he was hedged. By constantly entering, retracting, and re-booking fake trades, JK fooled SocGen’s computer systems and his supervisors.

After JK’s fraudulent positions were exposed in January 2008, SocGen commissioned its General Inspection Department to conduct an internal investigation of l’affaire Kerviel. Its report, entitled Mission Green Report, was published on May 20, 2008 and revealed 947 instances in which JK employed contract cancellation and modification to deceive his supervisors.327

Entering Pairs of Offsetting Trades at Artificial Prices

Another deceptive practice JK used was entering into two offsetting trades at fictitious prices to ensure either gains or losses, whichever best served his purposes. For example on March 1, 2007, he offset part of his excessively high 2007 earnings by purchasing 2,266,500 SolarWorld shares at €63 and selling them for €53, creating a fictitious loss of €22.7 million. SocGen’s Mission Green Report revealed 115 instances where he employed this method of deception.328

Posting Intra-monthly “Provisions”

SocGen’s systems gave new trading assistants the ability to improve biases in the bank’s front office models by entering positive or negative “provisions.” JK was no longer an assistant trader but he had access to and used this back door to conceal some of his fraudulent earnings. SocGen’s Mission Green Report revealed nine instances where he employed this method of deception.329 Between July 2007 and January 2008, they amounted to more than €3 billion.330

Navigating SocGen’s Dysfunctional Risk Management System

SocGen focused more on execution efficiency than fraud detection. Controllers often missed opportunities to detect JK because they did not centralize or share information and failed to double check if he followed through on his promises and statements. These supervisors and controllers acted a bit like football referees who spent more time admiring competing teams’ level of play than calling penalties for rule violations. Soc-Gen’s computer systems were supposed to be world-class, but JK knew they could be fooled by complexity. In fact, some of the bank’s important risk management reports relied on manual processing, increasing chances of errors and slowing confirmation and settlement. JK knew many ways to manage and manipulate SocGen’s risk management system. Seven of them were used frequently and are explained in this section.

Using Process Time Lags to Avoid Detection

Having worked in SocGen’s middle office, JK knew which trades were monitored only at month’s end and understood that trades with deferred starting dates were confirmed only a few days before their value dates. He realized that it could take SocGen as long as two weeks to settle, confirm, and clear trades, which gave him time to camouflage these transactions from internal control systems.

Using Net Positions to Hide Enormous Gross Positions

SocGen’s risk management system focused on traders’ net, rather than gross, positions. The logic was clear. Net risks equal zero for offsetting (buy and sell) positions that have identical assets, sizes, and maturities. But this is only true if there are offsetting positions. JK posted fictitious trades that gave an illusion that his net positions were zero or within limits when they were not. By monitoring only his net positions, SocGen’s risk management system was unable to distinguish whether JK had offsetting positions worth €50 billion or €50 million.

Exploiting Unrealized (versus Realized) Profits

SocGen’s back office monitored traders’ profits, but profits have two forms, realized and unrealized. JK’s fake trades distorted his performance because many of his gains or losses were unrealized. This difference was especially important to him because SocGen based traders’ bonus compensation on realized and unrealized profits. A more effective means to track JK’s results and behavior would have been to focus on his cash flows and to treat all of his transactions as if they had margin requirements—even if that meant assigning implicit margin requirements to all of his OTC transactions.

Playing the Law of Averages

SocGen’s middle office focused on controlling aggregate trade volume, positions, and margin payments of DLP and Delta One, rather those of its individual traders. Consequently, JK’s highly skewed activities were averaged into those of his unit and appeared less onerous than they actually were. Had controllers tracked his individual margin payments between April 2007 and November 2007, they would have realized that JK was responsible for 25 to 60 percent of his unit’s margin payments.331

Reluctance to Take Vacations

Vacations force traders to leave their desks, which enables banks to audit their books. SocGen required its traders to take at least one two-week vacation every year, but in 2007, JK took just four days’ vacation, and otherwise stayed very close to his desk. Between 2006 and 2007, this issue was raised four times by the head of Delta One, Martial Rouyère, but nothing was done, and there was no follow up.332

Recording Technical Counterparties

To buy time, JK often listed technical counterparties as the other side of his deals. The term, “technical counterparties” is a generic name that SocGen used for customers who were either (1) temporarily waiting to be classified, (2) not yet booked because contract terms were waiting to be finalized, or (3) internal SocGen counterparties (e.g., ClickOptions, which was a wholly owned SocGen subsidiary). Transactions with technical counterparties were confirmed only monthly by the back office.333 By listing them as counterparties to his transactions, JK added another level of complexity to his already complicated trades and positions, making detection even more difficult.

Dealing with Middle Office and Back Office Inquiries

SocGen’s middle office employees occasionally questioned JK about aspects of his positions and trades. One way he deflected these inquiries was to avoid speaking to the same middle office employee more than once. That way he could minimize SocGen’s institutional memory of his many suspicious deals. Another method was to provide answers that amounted to little more than financial gibberish and double-talk. SocGen’s staff members left these conversations confused but hopeful that JK’s incomprehensible explanations would find their way to correcting the problem.

Exploiting Supervisor Turnover

JK’s direct supervisor resigned on January 12, 2007 and left SocGen on January 26. For the next two and a half months, until April 1, JK was without a direct supervisor. In fact, during this period, DLP’s senior trader validated the group’s monthly earnings, and in March, JK was allowed to validate his own earnings.334 This lack of supervision was directly correlated with a significant spurt in his unauthorized positions.

In April 2007, Eric Cordelle was chosen to lead DLP, but he lacked extensive trading experience and SocGen provided him with insufficient institutional support. Cordell did not perform the analyses needed to detect JK’s problematic trades, positions, and cash flows. By July 2007, JK’s exposures had reached €30 billion. It is easy to assume that JK’s lack of supervision in 2007 from January to March and inadequate supervision from April to July were responsible for his enormous positions, but JK began defrauding SocGen before his old boss left. Consequently, the full breadth and depth of his illicit activities may never be known. The six deceptive methods listed in this section were only the most common he used.

How JK Was Caught

At the end of 2007, JK recorded eight fictitious forward contracts worth €30 billion, which were used to cover his exposures and offset most of his €1.4 billion gains in 2007. Originally, JK booked these transactions against ClickOptions, an internal SocGen counterparty, but shortly thereafter changed it to Baader Bank, a German brokerage company. After inquiries by SocGen’s middle office, JK claimed that he had canceled the trades.

On January 15, 2008, while preparing its 2007 annual report and calculating the bank’s regulatory capital requirements, a middle office employee (referred to in the Mission Green Report as Agent 6) spotted JK’s positions, their size, and the large amount of regulatory capital SocGen would need to hold against them. Because these trades were supposed to have been canceled, JK was contacted. On January 18, he changed his story and claimed that he made a recording mistake. The actual counterparty to these forward trades was not ClickOptions or Baader Bank but Deutsche Bank. To convince SocGen’s compliance officers that the trades were legitimate, JK forged two confirmation e-mails. Later that day, SocGen contacted Deutsche Bank directly and discovered that JK had lied.

During the January 19–20 weekend, JK’s fake trades, fictitious counterparties, falsified positions, and dishonest behavior were exposed by a team of twenty SocGen employees. Given the size of his long positions (i.e., €50 billion) and losses on them, SocGen was concerned about financial survival, noncompliance with French bank regulations, takeover opportunities, and other competitor reactions. CEO and Chairman Daniel Bouton contacted Christian Noyer, Governor of France’s central bank, and Michel Prada, Chairman of Autorité des Marchés Financiers, which regulates, authorizes, monitors, and investigates France’s financial institutions and products. Bouton pleaded with Prada for an exception to France’s notification rules. Before informing the stock exchange and media of SocGen’s scandal and losses, he wanted to unwind JK’s positions and arrange for a new equity issue. Prada gave Bouton three days.

Between Monday, January 21, and Thursday, January 23, SocGen liquidated all of JK’s positions and notified President Nicolas Sarkozy and Minister of Finance, Christine Lagarde. On January 24, SocGen notified the media and stock exchange, which temporarily stopped trading SocGen’s shares. Included in Bouton’s announcement was notice of a capital increase that would help remedy JK’s losses, as well as those associated with the bank’s deteriorating subprime positions.

To liquidate JK’s positions, Bouton called on Maxime Kahn, head of SocGen’s European options trading operations. Kahn thought these positions were those of a large client. Only after he completed his task, three days later, was he told they were SocGen’s own positions. Between the end of December 2007 and January 21 (Black Monday), the DAX fell by nearly 16 percent (see Figure 9.4), and JK’s losses grew to gigantic levels. Kahn’s sales drove down market prices even further. His rapid liquidation ripped off the band aid, but it did so at an extremely high price. Losses on JK’s positions amounted to €6.3 billion. When combined with his 2007 earnings of €1.4 billion, SocGen’s net losses were €4.9 billion (about $7.2 billion). About €1.5 billion (31%) of these losses occurred while JK was employed at SocGen, and the remaining €3.4 billion (69%) were the net result of SocGen’s three-day liquidation orgy from Monday, January 21 to Thursday, January 24.

During the rest of 2008, SocGen incurred additional losses but, remarkably, ended the year with a small profit. To revitalize its balance sheet and restore the bank’s Tier 1 regulatory capital ratio to 8 percent, SocGen floated a €5.5 billion (about $8.4 billion) equity rights issue, in March 2008, which was underwritten by JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley.

Paying the Piper

JK and his trading assistant335 were fired in February 2008. Eric Cordelle, head of DLP, was fired the following April for professional insufficiency, as were two others. Also in April, after seventeen years at SocGen, Daniel Bouton resigned as SocGen’s CEO but remained Chairman of the Board. Frédéric Oudéa, SocGen’s former Chief Financial Officer, took over as CEO after Bouton left.

On July 4, 2008, France’s Banking Commission fined SocGen €4 million ($6.3 million) for serious deficiencies in its risk management control procedures, which were supposed to separate the bank’s trading and control functions (i.e., front and middle offices).336 SocGen argued that it was unaware of these weaknesses, but the Commission decided this was no excuse for failing to meet national bank regulations. SocGen was also chastised for its unsecured computer system, inability to enforce internal trading-limits and monitor trades, stilted organizational structure, flaccid internal control and governance systems, and casino-type culture, as well as poorly developed risk management systems, techniques, policies, and procedures.

Slightly more than two years later, on October 5, 2010, JK was convicted of breach of trust, forgery, and unapproved data entry use of bank computers. He was sentenced by criminal court (Tribunal Correctionnel) to five years in prison but two of them were suspended. Of his three-year jail sentence, JK ended up serving only 110 days in prison and was freed in September 2014.

The court also required JK to make full restitution of his €4.9 billion losses, which was consistent with French legal history regarding indemnification. No one expected that JK would or could repay the total amount. On October 24, 2012, the Paris Court of Appeal upheld JK’s criminal conviction and prison sentence, as did France’s Supreme Court (Court of Cassation), on March 19, 2014, but the high court also took a second look at the harsh €4.9 billion repayment obligation. Citing severe weaknesses in Soc-Gen’s risk management systems and procedures, it canceled the €4.9 billion obligation and referred this restitution issue to the Versailles Court of Appeal. On September 23, 2016, the Versailles Court of Appeal ruled on Jerome Kerviel’s civil liability, ordering him to pay €1 million in compensation for the damages he caused.

One might have thought that JK’s legal battles had come to an end, but in a surprising turn of events on June 7, 2016, the Paris Labor Court ordered SocGen to pay JK €450,000 ($510,000). This included €300,000 for his unpaid 2007 bonus, €100,000 for wrongful dismissal, as well as compensation for damages, unused vacations days, and other contractual obligations. The Paris Labor Court believed that SocGen must have known about JK’s trades and positions, and, by taking no serious disciplinary actions, implicitly approved them. In short, even though JK’s actions were illegal, the Labor Court found they offered no real and serious cause for dismissal because SocGen was complicit.

SocGen promised to appeal the ruling, calling it scandalous, but there was another important reason for challenging this decision. If it could be proved that SocGen had (1) full knowledge of JK’s deeds, (2) purposefully refused to institute proper control systems, or (3) incurred financial damages as a result of obvious shortcomings in the organization or application of its own control systems, then JK’s losses were not tax deductible. SocGen would owe the French government more than €2.2 billion in back taxes!

Did SocGen Know about JK’s Fictitious Trades?

JK was one of eight members (seven traders) at the DLP desk and one of 2,000 traders employed at SocGen. His actions were illegal and violated both business ethics and societal standards of trust and honesty. He was eventually caught and sent to prison, albeit briefly. JK admitted he was guilty and claimed that he acted alone, but it is hard to come away from this saga without sensing that a significant part of the blame lies with SocGen.

JK testified that his trades were unauthorized but not invisible to SocGen’s back office, middle office, and supervisors. He thought that SocGen’s silence, while he was profitable from 2005 through 2007, was tacit approval that his trades were implicitly approved. He also felt validated by others at SocGen, whom (he claimed) engaged in similar trades. Some of the facts:

–In 2005, JK earned €500,000 on an unauthorized short position in Allianz shares.337 His supervisor discovered the position but reacted with only a non-formalized verbal reprimand during a meeting with JK and his line managers. The supervisor also held a special meeting of the entire Delta One team to alert them to their trading limits and obligation to stay within them.

–Between late July 2006 and September 2007; SocGen managers ignored sixty-four alerts from its own middle office, which were either directly or indirectly related to JK’s fraudulent positions.338 Auditors also warned SocGen about its weak internal controls, but their notifications and admonishments seem to have been ignored.

–On March 13, 2007, the bank’s back office paid margin amounting to €699 million, due to JK’s positions.339 On two occasions in July 2007, DLP borrowed €500 million to finance JK’s margin calls.340 Between December 28, 2007 and January 1, 2008, SocGen paid margin equal to about €1.3 on behalf of DLP, mainly due to JK’s trades.341 Between January 1 and 18, 2008, SocGen’s back office ran out of bonds to meet margin requirements and resorted to paying them in cash.342 On five occasions, during this period, these payments were in excess of €500 million. In each case, JK’s supervisors failed to do the analysis needed to link these margin calls to any single trader.

–In March 2007, the French banking commission notified SocGen about the weak internal policies and procedures used by its equity derivatives department. In October 2007, Eurex alerted JK’s supervisors about Kerviel’s purchase of 6,000 forward contracts within a two-hour span, amounting to €1.2 billion. These trades were wildly above DLP’s daily limit on Eurex.343 Similarly, in November 2007, Eurex trading floor inspectors and exchange officials sent SocGen two cautionary letters of inquiry regarding JK’s trading activities on DAX.

–DLP paid €6.2 million in brokerage fees, mainly due to JK’s trades and propensity to overcompensate for these services. These (seemingly) excessive payments were not analyzed or investigated by his supervisors. 344 Until January 2008, JK’s internal and external (exchange-determined) violations of intraday and interday limits had no serious consequences. After 18 days of trading in January 2008, his fraudulent positions and deceptive practices were uncovered and prosecuted.

Short of implementing new risk management tracking and monitoring systems, SocGen could have exposed JK’s scam by asking one question: “Why are we paying so much margin when our positions are supposed to be hedged?” JK had gone to great lengths to make it seem as if his mountain of derivative exposures was hedged. Yet, SocGen willingly made large margin payments to support his positions. If JK was truly hedged, margin payments should have equaled margin receipts. Therefore, one key to exposing JK was to follow his cash trail, but SocGen’s ineffective IT and risk management systems made this task problematic. FIMAT Frankfurt, which was responsible for clearing SocGen’s futures transactions on EUREX, had daily records of each trader’s initial margin requirements, but SocGen’s middle office never analyzed them. 345

Network Incentives: Why did JK Go Undetected for So Long?

SocGen’s Mission Green Report found “that neither JK’s hierarchical superiors nor his colleagues were aware of the fraudulent mechanisms used or of the size of his positions. Only transfers of JK’s earnings to other traders (at a level of EUR 2.6 million) have been uncovered, without having any direct link to the fraud.”346 You might think that JK’s chances of detection were extremely high because anyone (e.g., any supervisor, middle office or back office employee, auditor, exchange staff member, or colleague) could have blown the whistle and exposed his reckless and deceitful behavior. They did not, and one reason might be incentives, which were more likely to protect than expose him. Consider the networks surrounding JK and the financial stakes they had in his continued success.

JK’s supervisors had incentives to remain silent because their bonuses were tied directly to the profits he earned. Cutting him meant cutting themselves. Similarly, back office and middle office employees were likely to have suppressed and sugar-coated their suspicions, especially if their alerts had a history of falling on deaf supervisors’ ears. As is common in many cases of front office deception, back office and middle office alerts are often dismissed, diffused, or otherwise discounted by supervisors when they are interpreted as needless cost-center meddling in profit-center business.

Exchanges have trading and position limits, which they are supposed to enforce. It is relatively easy for them to spot traders and institutions that exceed their trade or position limits. At the same time, traders who exceed their limits increase exchange volumes, which raises revenues, profits, and liquidity, as well as providing investors with sharper prices and greater flexibility—especially in terms of exit strategies. Instead of closing down traders who exceed their limits, exchanges often temporarily increased them.

Where were the regulators who were employed to monitor, supervise, and control the risks of financial institutions like SocGen? Effective regulation requires (1) financial institutions to report in a timely and transparent fashion and (2) watchdogs to carefully read and analyze these reports. History has shown that troubled firms often file translucent and untimely reports, and regulators, who are supposed to be reviewing them, fall down on their responsibilities.

Finally, colleagues are often the most likely to know about a trader’s improper trading methods and strategies—especially if they are working side-by-side with the rogues. But colleagues’ bonuses and reputations are often tied closely to those of their divisions, departments, and units. Furthermore, reporting suspicions that a successful colleague is falsifying trades and positions is serious. If proven to be true, the whistleblower’s bonus income could fall. If proven false, a number of outcomes could occur, such as employment termination or worse. Successful traders are often the first to be promoted. Therefore, colleagues who report rogue traders may be putting nooses around their own necks when these rogues become their bosses. Finally, work environments engender personal friendships backed by small and large acts of kindness. Loyalties and friendships also offer reasons why colleagues might be reluctant or unwilling to expose one another.

SocGen’s Bonus Incentives

In 2000, when JK began working in SocGen’s compliance department, his annual salary was €35,000, with no bonus. After transferring to the Delta One unit, this changed dramatically. In 2005, his annual salary had increased to €48,500, and in 2006, JK earned total compensation of €134,000, composed of a fixed salary of €74,000 and bonus of €60,000. In 2007, JK’s fixed salary was increased to €100,000, and he expected to earn a €300,000 bonus.

Bonus compensation is supposed to align employee incentives with those of shareholders, but it can create unintended harmful results. If this compensation was structured like a long forward contract, bonuses would rise as traders’ returns increased above their targets, but traders would be required to compensate the bank if they fell short. Most bonuses do not work that way. Instead, they offer traders higher rewards as their profits rise but do not require traders to compensate the bank when returns fall below targets. Therefore, bonus compensation is asymmetric, like a long call, which may encourage traders to take speculative risks (i.e., “What do I have to lose?”).

Doubling Strategies, Prospect Theory, and Survival Theory

When asked to explain how he made such massive returns in 2007, JK claimed that he had found a martingale, which is a gambling strategy based on continually doubling the stakes. The essence of a martingale is captured in the expression: “Double or nothing,” but it goes deeper than that. A pure doubling strategy increases the stakes by a multiple of two each time a trader loses and resets the strategy to zero each time the trader wins.

There are two consistent, but seemingly conflicting, truths about doubling strategies, which should be explained. First, individuals who use them have a 100 percent chance of winning an amount equal to their original bets, and second, individuals who use them have a 100 percent chance of eventually going bankrupt. How can both of these facts be true?

To understand doubling, consider a simple game with two possible outcomes, each having a 50 percent chance of occurring, such as flipping a fair coin. In this context, fair means each flip is independent from the previous ones. Therefore, the past cannot be used to predict the future. Someone using a doubling strategy has a 100 percent chance of eventually earning a return equal to the initial trade because the first win erases all accumulated losses and provides a return equal to the initial bet. These conclusions remain the same even if the probability of winning a two-outcome bet is not 50 percent.347

An example: Suppose an equity index can either rise or fall and a trader bets on the direction. He starts by betting $100 that it will rise and doubles his bet with each loss. Table 9.1 shows the results. On the first bet he loses $100. So, he doubles his bet to $200 and loses again. Now his cumulative losses equal $300. So, he doubles his last bet with a $400 (i.e., 2 × $200) wager, only to lose again. At this point, his cumulative losses equal $700. On the fourth try, he bets $800 (2 × $400), loses again, and has now spent a total of $1,500. Finally, on the fifth try, he bets $1,600 (i.e., 2 × $800) and wins. As a result, he earns $100 (his original bet).

Table 9.1: Gains and Losses from a 50-50 Doubling Strategy

As the number of investment tries increases, the trader’s return on total funds invested falls geometrically. Success on the first try causes a return of 100 percent (i.e., $100/$100 = 1.0) because the trader receives back $200 on a $100 bet. By contrast, success on the fifth try implies a return of only 6.25 percent (i.e., $100/$1,600), and if the number of investment tries rises to 10 before a win, the return on total funds invested falls to a miniscule 0.2 percent (i.e., $100/$51,200) because the absolute return stays the same at $100, but invested funds rise exponentially.

To guarantee a win, traders need to be assured that they can play an infinite number of times. In reality, this would not occur because the cost of investing after each successive loss would become too expensive. For example, if the trader lost ten times in a row, the cost to play the eleventh time would equal $102,400 and the cost to play the twenty-first time, after twenty consecutive losses (i.e., four business weeks) would equal $104.9 million. At these levels, it would also be difficult to find a willing and able counterparty.

Other financial institutions that fell victim to doubling strategies were Barings Bank, Long-Term Capital Management, and Amaranth. Baring Bank lost $1.3 billion in 1995, due to the deceptive deeds of Nick Leeson, 75 percent occurring during the last month. In 1998, Long-Term Capital Management lost $4.5 billion, with 50 percent occurring during the last month. Finally, Amaranth Advisors LLC lost more than $6 billion in 2006, with 70 percent occurring during the last week. In each case, problems arose because of the rapid speed with which positions and underlying price volatility increased.

Prospect and Survival Theory

JK’s behavior has a basis in both prospect theory and survival theory. Prospect theory suggests that individuals are willing to take greater risks to avoid losses than they are to increase gains. Therefore, traders with winning portfolios are likely to stick with their positions, fearing that that any large additional trades might blemish or ruin their existing gains at evaluation time. By contrast, if they have losing positions and evaluation time is approaching, they are more likely to double down and increase the stakes in order to recover their losses quickly.

Survival theory offers the same conclusion. Trader A, who uses a doubling strategy and manages to pass periodic performance evaluations, becomes a survivor. Trader B, who uses the same strategy but makes opposite bets, is likely to be fired or worse, bankrupt the company. Either way, the chances of Trader B surviving are low, which eliminates him from the sample pool. If positive returns at evaluation time cause affirmative performance assessments, regardless of volatility during the interim period, rational traders are likely to use doubling strategies when their returns are negative and stop using them when their returns are positive.

If prospect and survival theories are correct, it might seem easy to spot traders using doubling strategies. The quick test would be to see which ones had significant increases in their trading volume just before evaluation. JK’s positions were not transparent. He engaged in outright fraud, forgery, and other forms of deceit. As a result, catching this type of behavior requires other surveillance methods.

SocGen’s Risk Management Reforms

Given the multifaceted nature of JK’s deceptions, there were some obvious holes in the bank’s security systems and governance structure.348 L’affaire Kerviel prompted SocGen to make a number of wide-ranging changes to its security and control systems. Under the banner name, Fighting Back, SocGen spent more than €200 million to improve its security and operational efficiency, as well as strengthen the bank’s risk, compliance, and monitoring functions. The bank’s customer strategy and business model were refocused, computer access was restricted, and other computer security measures employed. The middle office began evaluating gross and net trader positions.

SocGen’s Fighting Back reforms also addressed bonuses by capping compensation, deferring it, and basing calculations on several years’ performance instead of just one. Clawback provisions were also added to address situations in which current gains were followed by future losses. Instead of constructing bonuses solely on the size of traders’ returns, SocGen also considered their methods, risks, and conduct.

Fighting Back also sought to create a new risk culture that might instill in SocGen traders an ethical heart. These efforts focused on building values, responsibility, commitment, team spirit, and innovation, as well as raising general awareness of fraud and the penalties of fraudulent practices. The bank incorporated these risk-culture reforms into its hiring, training, evaluation, and promotion practices. Finally, SocGen’s reforms included plans to strictly monitor and enforce vacation days taken by traders.

Conclusion

JK cunningly defrauded SocGen by gaining access to its back office and middle office computer systems, entering fictitious trades, and canceling or modifying them to suit his best interests. He played SocGen’s security systems like a harp, using internal and external counterparties, as well as market and off-market prices to avoid detection. By making his transactions stealth-like and complex, he was able to slow security confirmation and settlement speeds, providing time to take large unauthorized positions from which he might profit.

After his exposure and conviction, public opinion on JK was split. A stream of critical and sympathetic books followed. Of course, SocGen and many others saw JK as a financial demon who willingly violated company regulations, French laws, and ethical standards. But a broad segment of observers (especially French residents) viewed him and the situation differently, heralding JK as a Robin Hood-like hero – someone SocGen exploited while he was a cash machine but afterwards tried to use as a corporate scapegoat. In the words of JK’s lawyer, Elisabeth Meyer: “If Jérôme’s operations were still profitable, would they [SocGen] have filed charges?”349

His popularity encouraged the sale of JK T-shirts (e.g., Kerviel is my boyfriend) and hats (e.g., got jerome?), as well as coffee mugs and water bottles (e.g., #jerome). Supporters wrote songs (e.g., Jerome Kerviel is a Market Man), recorded albums (e.g., Kerviel Blues), and formed JK Facebook groups (e.g., Jerome Kerviel Should Be Awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics). JK wrote a book, entitled L’engrenage: mémoires d’un trader (The Gears: Memoirs of a Trader), which was turned into a sympathetic movie.

JK provided a substantial, but temporary, existential threat to SocGen. To its credit, the bank remained solvent and even earned a small profit in 2008. While the global financial community took notice, French, European, and other international financial systems were barely affected by JK’s losses. In the end, SocGen learned a good but costly lesson about the need for effective monitoring and control systems. The broader financial community was also reminded of a few important lessons, one of which was financial shocks are bound to happen and will continue to occur in the future. “Where there’s a will there’s a way,” meaning dishonest employees will always find secret paths to company vaults. Reducing or preventing such incidences is important but equally so is the need to widen, deepen, and stabilize the global financial system so that disasters, like this, are minor firecrackers rather than major explosions.

Review Questions

- Explain why the promotion of JK from a middle office position to the front office at SocGen was a recipe for disaster.

- Explain why premiums on turbo warrants are lower than premiums on plain calls or puts.

- Explain how to arbitrage a down-and-out turbo warrant. Is it the same as arbitraging an up-and-out put warrant?

- Explain whether you feel JK’s profits on forward sales of Allianz AG stocks, in 2005, were by skill or luck.

- How did JK hide his €1.4 billion profit in 2007? Did he use the same basic methods in 2008, when he hid losses?

- How did JK use contract cancellations and modifications to mask positions and risks?

- How did JK use intra-monthly “provisions” to deceive his supervisors and middle-office staff?

- How did JK’s knowledge of SocGen’s dysfunctional risk management system help him mislead SocGen supervisors and middle-office staff?

- Explain the role “supervisor turnover” may have played in spurring JK’s deceptive practices.

- How was JK caught?

- Do you believe SocGen knew about JK’s illicit trades prior to his spectacular losses in 2008?

- Using the concept of “network incentives”, explain why JK’s deceptive practices may have gone undetected for so long.

- Using a doubling strategy, what are the eventual chances of winning? How much? What are the eventual chances of losing and going bankrupt? Explain.

- In the context of SocGen and JK, explain “prospect theory” and “survival theory.”

Bibliography

Anonymous (July 4, 2008). “Société Générale Is Fined for Breaking Rules,” The New York Times. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/04/business/worldbusiness/04i-ht-socgen.4.14250276.html. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

Bank for International Settlements. Basel II: Revised International Capital Framework. Available at https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbsca.htm. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

Brown, S. J., & Steenbeek, O. W. (2001). “Doubling: Nick Leeson’s Trading Strategy.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 9(2), 83-99.

Brown, S. J., Goetzmann, W. N, and Ross, S. A. (1995). “Survival.” The Journal of Finance, 50, 853–873.

Canac, P., & Dykman, C. (2011). “The Tale of Two Banks: Société Générale and Barings.” Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies, 17(7), 11–32.

Hunter, M., & Smith, C. (2011). “Société Générale: The Rogue Trader,” Insead Case Studies, INS227.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decisions under Risk.” Econometrica 47, 263-291.

Marthinsen, J. E. (2010). “Derivative Scandals and Disasters.” In R. W. Kolb & J. A. Overdahl (Eds.), Financial Derivatives: Pricing and Risk Management, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 313–332.

Nicholson, C.V. (17 November 2010) Kerviel: Bosses Never Said a Thing, New York Times. Available at https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/11/17/kerviels-comeback-they-never-said-a-thing/?m-trref=www.google.com&gwh=835A051755380596953348E13DFADD0F&gwt=pay. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2008, May 23). Société Générale: Summary of PwC Diagnostic Review and Analysis of the Action Plan. Available at https://www.societegenerale.com/sites/default/files/23%20May%202008%20The%20report%20by%20audit%20firm%20PWC.pdf. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

Société Générale “Was Aware” of Deals by Rogue Trader Kerviel. (May 18, 2015). France24. Available at http://www.france24.com/en/20150518-france-societe-generale-bank-aware-knew-kerviel-deals-rogue. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

Société Générale. (2008, February 20). Mission Green: Summary Report Interim Conclusions on 20 February 2008. Available at https://www.societegenerale.com/sites/default/files/12%20May%202008%20The%20report%20by%20the%20General%20Inspection%20of%20Societe%20Generale.pdf. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

Société Générale. (2008, May 23). Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of Société Générale. (2008). Available at https://www.societegenerale.com/sites/default/files/23%20May%202008%20The%20report%20of%20the%20Special%20Committee%20of%20the%20Board%20of%20Directors%20of%20Soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9%20G%C3%A9n%C3%A9rale.pdf. Accessed on January 22, 2018.

Weisman, A. (2002). “Informationless Investing and Hedge Fund Performance Measurement Bias.” Journal of Portfolio Management 28(4), 80–92.