CHAPTER 4

Reaction Objectives

Any project leader, program coordinator, or facilitator desires a positive reaction to his or her efforts. Unfortunately, the terms positive and reaction are vague. Sometimes a specific reaction to the project or program is desired. While Level 0 (Input) objectives set the scope of the program, Level 1 (Reaction) objectives tell us what initial success to expect. Projects can go astray with an adverse reaction. If participants view program content or project intent as irrelevant, the likelihood that anything will change is slim. Consequently, defining the desired reaction through a reaction objective is an important step toward ensuring results that meet stakeholder expectations. This chapter explores topics for reaction objectives, as well as how they are constructed and used.

ARE REACTION OBJECTIVES NECESSARY?

Some might argue that reaction objectives are always understood and do not need to be spelled out. Of course we want a favorable reaction. However, reaction objectives should be stated for three fundamental reasons.

First, reaction is a vague, subjective construct that needs clarification if we want to ensure we get the reaction we seek. Objectives provide the basis for this clarification. For example, at times the reaction objective is based on motivating participants. In other situations, the reaction objective explains why they’re there. So the reaction objective answers the question, “What’s in it for me?” Sometimes the objective is to avoid a negative reaction, because the project or program is controversial. At other times, reaction objectives show that the program is necessary and appropriate for members of the target audience and their role in the organization. Definition is needed.

Second, programs can fail if the reaction is unfavorable (that is, the desired reaction is not achieved). An example is a project perceived to be controversial because it changes the way in which the group works by adding extra tasks to the schedule or removing freedoms that the group previously enjoyed. These situations can provoke a negative reaction; therefore, the objective would be to present the project in a logical, rational way so participants can see that it is necessary. At best, this approach would foster an understanding of the importance of the new approach with participants’ willingness to apply necessary actions. At worst, it would prevent participants from sabotaging the success of the project. If the project were perceived to be negative, its value in terms of learning application and impact would be practically dead because of the adverse reaction. Consider a traditional learning and development program. If participants don’t find it useful or helpful, the experience will be generally unpleasant, possibly causing them to miss important concepts necessary for application and, ultimately, impact. Hence, there would be little to no learning, which then leads to little or no application or business impact.

Third, clearly defined reaction objectives are needed because they represent the first level of project or program success. The chain of impact begins at this level. While reaction is undervalued by sponsors and clients, the objectives are important to those people intimately involved in implementing the program. The irony is that in most projects, reaction is captured, but objectives have not been developed. This leaves the data derived from an evaluation, to some extent, useless. The basis for evaluation is derived from the objectives. Without them, how can success be determined?

The question remains: Are reaction objectives absolutely necessary? It depends. Do you want to measure reaction and hope the results are understood? Or do you want meaningful measures that will provide some direction toward higher levels of success? If you answer “yes” to the latter, then you need reaction objectives.

HOW TO CONSTRUCT REACTION OBJECTIVES

Developing reaction objectives is quite straightforward. They’re easy to develop and easy to measure, taking very little time. There are five issues to keep in mind when developing reaction objectives.

Descriptions of Perception

By definition, a reaction objective is based on the perception of those involved in the program or project. Perception is essentially a measure of how someone reacts to the objective. Descriptions of perception vary. The key is to be clear on what perception is needed to ensure participants are engaged and willing to acquire the knowledge, skills, or information required to change what needs to change. Table 4.1 shows the different keywords for objectives to reflect reaction.

| Table 4.1: Keywords for Reaction Objectives | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Example: participants should perceive this program to be relevant to their work, as indicated by an average of 4 out of 5 on a 5-point scale. | ||

Specificity

Sometimes objectives reflect a certain degree of reaction. If a 2-point scale is used (yes or no, favorable or unfavorable), planning for a percentage of “yes” or “favorable” responses may be the precision that’s needed. On a 5-point scale, measuring the percentage rating 4 out of 5 would be appropriate. Sometimes even decimal points are used (that is, 4.2 out of 5), although the incremental parts of a 5-point scale might have no actual meaning from a quantitative standpoint. Sometimes a 7- or 10-point system is used in setting objectives and measuring success, although a 10-point scale is usually not the most appropriate for this type of evaluation. Five to 7 points represents enough variance in the scale to give respondents the choices they need. The idea, however, is to identify a specific degree of success, regardless of the type of question or scale.

This specificity may be based on historical results and then correlated with a specific level of performance. Specificity of the measure may also represent a slight increase over the typical reaction results. Sometimes the degree of success is arbitrary due to insufficient baseline information. In either case, it is important to set the specific desired measure of success and know why you have set it at that level.

Number of Objectives

While the principal issue in developing objectives is precision, the challenge is to avoid having too many reaction objectives. After all, in the success value chain, reaction is perhaps the weakest level of feedback, at least from an executive viewpoint. Overkill needs to be avoided. Identify only the most critical reaction issues, and develop specific targets of success to make the measure meaningful.

Content Focus Versus Noncontent Focus

An important consideration in developing reaction objectives is to obtain data about the content of the program. Too often, feedback data reflect aesthetic issues that may not reflect the substance of the program at hand. Take, for example, an attempt to show the value of a sales and marketing program that focused on client development. The audience consisted of relationship managers—those individuals who have direct contact with the customer. This particular program was designed to discuss product development and a variety of marketing and business development strategies. An appropriate set of reaction objectives would include those that represent content or the presentation of content on product development, marketing, and business strategies. Table 4.2 shows the comparison of measures explored on a reaction questionnaire. The traditional way to evaluate these activities is to focus on noncontent issues. As the table shows, the column on the left represents areas important to activity surrounding the session, but few measures related to content. The column on the right shows more focus on content, with only minor input on issues such as the facilities and service provided. This is not to imply that the quality of the service, the atmosphere of the event, and the quality of the speakers are unimportant. They are and should be addressed appropriately. A more important set of data, however, is detailed information about the perceived value of the program, the importance of the content, and the planned use of material or a forecast of the impact—indicators that positive results did and will occur. This is underscored by the shift occurring in the meetings and events industry, which is moving from measuring entertainment to measuring meaningful reaction, learning, and even application, impact, and ROI.

| Table 4.2: Comparison of Content Versus Noncontent Objectives | |

| Focus on Noncontent Issues | Focus on Content Issues |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key Concepts

Table 4.3 shows the criteria involved in creating reaction objectives. The table also presents 10 of the most important reaction questions to ask. Along with these questions, additional topics are addressed in reaction objectives, as described in the next section.

TOPICS FOR REACTION OBJECTIVES

Many topics serve as targets for reaction objectives, because so many issues and processes are involved in a typical project or program. Reaction is important for almost every major issue, step, or process to make sure outcomes are successful. Table 4.4 shows typical topics of objectives. The list reveals possible reactions to a project or program, beginning with readiness and moving through a variety of content-related issues to recommendations to others.

CRITERIA FOR THE BEST REACTION OBJECTIVES

- Identify important and measurable issues

- Are attitude based, clearly worded, and specific

- Underscore the linkage between attitude and the success of the program

- Represent a satisfaction index from key stakeholders

- Can predict program success

KEY QUESTIONS

- How relevant is the program?

- How important is the program?

- Are the facilitators effective?

- How appropriate is the program?

- Is this new information?

- Is the program rewarding?

- Will you implement the program?

- Will you use the concepts/advice?

- What would keep you from implementing objectives from the program?

- Would you recommend the program to others?

Ready

Many programs fail because of inadequate preparation by participants or perhaps involvement of the wrong participants. An objective could focus on ensuring that the right people are involved and that they are prepared for the project.

Useful

Although this might seem apparent, the project or program must be useful to participants. In far too many situations, it is not useful, and its benefit to the organization isn’t clear. Consequently, usefulness is an important reaction objective.

Necessary

For some projects, it’s important for participants to realize the need for an initiative. This type of objective might be appropriate for implementation of a new ethics program or cost-containment project for health care, as employees must see that action is necessary.

Appropriate

A project or program needs to be appropriate for the situation. Sometimes mismatches occur between the program and the problem. Participants need to see that this is the appropriate action to take given the situation at hand.

Motivational

Some projects or programs are designed to motivate employees to improve performance or reach a goal. The important issue is to make sure participants are motivated to take action. This is particularly helpful for reward systems, meetings and events, and leadership development programs or projects.

Rewarding

Some projects need to be rewarding for participants and other key stakeholders. This is particularly true for projects such as an employee suggestion system where cash rewards are provided for submitting a suggestion; a pay-for-skills program where employees are rewarded with promotion if they learn new skills; or a compensation system that rewards employees directly for performance. Employees must see these projects as rewarding; otherwise, their involvement may be limited.

| Table 4.4: Topics for Reaction Objectives | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Practical

In a world of complex workplace issues, practicality is imperative. Projects or programs should provide a practical application, devoid of unnecessary theoretical issues.

Valuable

One of the most powerful objectives focuses on the value of a project. Participants need to see value, as it benefits both them and the organization. Value can be expressed in terms of a good investment by the employer or a good investment of the participants’ time. In some situations, program owners want participants to view the program as valuable enough that they will take the appropriate actions during and after the program.

Timely

Some projects need to be perceived as timely—not too early and not too late. This is particularly important for new technology, new tools, or training for new jobs. Employees see these projects as timely in their implementation. When employees are promoted into new jobs, they want new skills and new technologies. The programs and projects that offer these skills and technologies should be timely so employees can apply them in their new role.

Powerful

To achieve dramatic improvement or urgent action, a project might need to be perceived as powerful. This is particularly important for breakthrough processes, exciting technology, and new approaches to old problems (that is, new content and completely new skills). Participants need to see this material as making a powerful impact on them and their work life.

Leading Edge

Some projects are implemented to stay ahead of others—to stay on the leading edge of technology or processes when compared to competitors. This is important when new systems are implemented and new products are developed. Employees and others involved need to see them as advanced or visionary.

Just Enough

Some projects contain more information than participants want to use or be involved with—too many unneeded or unwanted parts. An ideal project or program has just enough information. This is a key objective for training programs where information is provided at a rate that allows employees to learn what they need to do and nothing more.

Just for Me

Some projects need to be tailored to individual participants. This is helpful for programs that are specific to an individual’s needs, as in training, coaching, or performance improvement processes.

Efficient

All programs need to be implemented efficiently. Those involved need to see organization and precise execution. People do not react favorably to inefficiency. They must see the efforts to make a project smooth and efficient.

Easy/Difficult

Project participants need to find the effort easy or at least not too difficult to accomplish. If it becomes too difficult, participants avoid it, or do it improperly, resulting in problems. In some cases, there needs to be an appropriate balance between too easy and too difficult.

Service-Related

A lot of projects involve support groups or others who provide service to the team. Service could mean making the process more conducive to work, the atmosphere more conducive to learning, or the setting more enjoyable and entertaining. This is particularly true for meetings and events, where the service provided for the hotel is a critical issue. It’s also important when project leaders and other staff provide excellent feedback and service to support all participants.

Relevance

Participants want to learn information, skills, and knowledge that is relevant to their work. Consequently, it is helpful to explore the relevance of the program or project to the participants’ current work or future responsibilities. If it is relevant, more than likely it will be used.

Importance

Participants need to see that the content is important to their job success. This provides an answer to “What’s in it for me?”

Intent to Use

Asking participants about their intentions to use the content or material can be helpful. The extent of planned use can be captured, along with the expected frequency of use and the anticipated level of effectiveness when using the information, skills, and knowledge. Intent to use usually correlates to actual use and is important for enhancing the transfer of learning to the job.

Planned Action

While asking participants the extent to which they intend to use knowledge, skills, and information acquired during a program or project is important and is often a predictor of actual use, it is sometimes important to capture their actual planned actions. An objective reflecting the need for participants to identify three to five planned actions gives them focus throughout the program.

New Information

In too many situations, programs simply rehash old material or address the same problem. Sorting out what is considered new information and what is old information can be helpful.

Overall Evaluation

Almost all organizations capture an overall satisfaction rating, which reflects participants’ overall satisfaction with the project or program. While this might have very little value in terms of understanding the real issues and the program’s relationship to future success, comparing one program to another and with the programs over time might be helpful. Because the data can be easily misinterpreted and misused, other areas might provide a better understanding of needed adjustments or improvements.

Content

Program content includes the principles, steps, facts, ideas, and situations presented in the program. The content is critical, and participant input is necessary.

Delivery

Because programs can be delivered in a variety of ways, objectives about the appropriateness and effectiveness of the delivery method might prove helpful. Whether delivery is by case studies, coaching, discussion, lectures, exercises, or role plays, understanding the effectiveness of the process from the perspective of the consumer is important.

Facilities/Environment

Sometimes, the environment is not conducive to learning. Feedback can identify issues that need attention. These types of data include the learning space, the comfort level in the learning environment, and other environmental issues, such as temperature, lighting, and noise. A word of caution: If nothing can be done about the learning environment, then data surrounding the environment should not be collected.

Facilitator/Team Leader Evaluation

Perhaps one of the most common uses of reaction data is to evaluate the facilitator. If properly implemented, helpful feedback data that participants provide can be used to make adjustments to increase effectiveness. The issues usually involve preparation, presentation, level of involvement, and pacing of the process. Some cautions need to be taken, however, because facilitator evaluations can be biased either positively or negatively. Other evidence might be necessary to provide an overall assessment of facilitator performance.

Recommend to Others

When participants are voluntarily involved in projects and programs, it is important to create a need for still others to participate. If this is the case, having an objective that focuses on the extent to which employees recommend the project or program to others can be extremely helpful. Word-of-mouth recommendations might be the strongest endorsement for a program and the most effective marketing tool. This can be powerful for external programs at universities, workforce development programs at community colleges, corporate training and development, and major conferences.

HOW TO USE REACTION OBJECTIVES

Level 1 reaction objectives can be used in several ways. Although, in the eyes of some clients and sponsors, they are the least useful objectives, they still should be developed and used properly. Here are a few possibilities.

Program Design

Because most reaction questions focus directly on content, low ratings might signal that content isn’t relevant, useful, practical, timely, motivational, and so forth. The designers and developers can use this information to make adjustments so that content sparks the reaction desired.

Program Delivery and Implementation

Those involved in delivering, implementing, or organizing a project or program need objectives about the planned success of the process. Some key reaction objectives focus directly on how they have organized, delivered, and supported that process. Objectives let them know how to design for the reaction that the program owner desires.

Communication to Participants

Sometimes participants need to understand the intended reaction. This keeps them aware of the collective effort of the entire team and its goals at this level. Otherwise, they might wonder what reaction was desired.

Facilitator Evaluation

Perhaps the most immediate reaction objective is the evaluation of the facilitator or team leader. In learning and development, leadership development, coaching, and process improvement, the facilitator needs feedback. The facilitator sees his or her role as ensuring that participants had a highly favorable reaction to every aspect of the project; therefore, he or she wants to know how the team reacted. For other projects where there are no formal learning and development efforts, the evaluation of the team leader might come into play. Much of the feedback goes directly to that person.

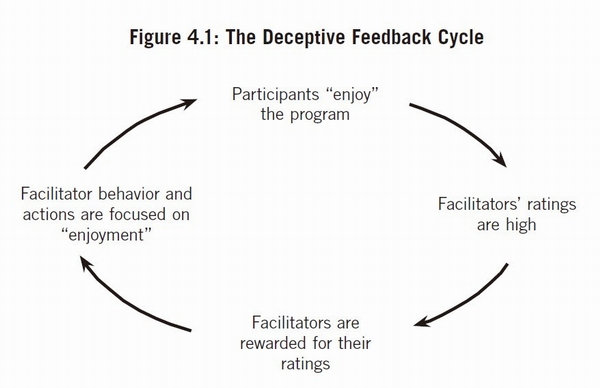

The Deceptive Feedback Cycle

There is a danger of placing too much reliance on reaction, particularly using it for facilitator evaluation. The learning and development field has a history of playing games with Level 1 objectives and data. The objective is for the participants to enjoy the program, and the facilitator is the centerpiece of that enjoyment. As shown in Figure 4.1, if participants enjoy the program, the facilitator ratings are often high (Dixon, 1990). Consequently, in many organizations, facilitators are primarily rewarded on those ratings. When that is the case, they naturally focus on creating an enjoyable experience. Certainly, nothing is wrong with enjoying the program. A certain level of enjoyment and satisfaction is an absolute must, but not at the cost of content. As some of our professional colleagues say, “We quickly migrate to the business of entertaining instead of the business of learning.” To avoid this, several actions can be taken:

- Facilitators should be evaluated on Level 2 (Learning), Level 3 (Application), occasionally Level 4 (Impact), and maybe even Level 5 (ROI). This keeps a balanced perspective and prevents an overreliance on reaction objectives.

- Evaluation objectives should focus primarily on content-related issues, as described in this section. Facilitator ratings are but a small part of the experience.

- The value of Level 1 objectives has to be put into perspective. From the point of view of clients and sponsors, these data are not very valuable. In fact, many sponsors consider them essentially worthless. This is not so for other stakeholders—the designer, developer, facilitator, and participants, for example. But for the individual funding the program, reaction objectives have very little value.

EXAMPLES

Writing reaction objectives is quick and easy. The action verbs in Table 4.1 can be combined with the topics presented in Table 4.4 to present simple reaction measures. Additional precision can be offered with desired ratings or the percentage rating “yes” compared to “no.” Scales from 1 to 10 or even zero to 100 have been used to judge the reaction; however, 5-point and 7-point scales are most often used as they provide sufficient variance in scoring for this type of measurement.

Examples of reaction objectives from one project are presented in Table 4.5. These are the reaction objectives taken from an annual conference of insurance agents. In this situation, the program designer desired very specific reactions and set the objectives indicated in the table (Phillips, Myhill, & McDonough, 2007).

FINAL THOUGHTS

In this chapter we’ve outlined the steps to develop reaction objectives—a simple process. Often understood, but not specifically written or communicated, these objectives are far more effective if clearly spelled out for all parties. Reaction is important, as a negative reaction can doom a project to failure. Reaction objectives pinpoint the areas critical to project success. This chapter details how these objectives are developed and presents 27 possible areas to evaluate. Taken in its total, this is far too many. The critical challenge is to select only the measures most important to the project, providing the information that the various stakeholders need. Then the data must be used to make adjustments and changes, but not be overemphasized. These data, after all, are perceived as less valuable in the eyes of many program owners and sponsors. Relying on it as the key measure for facilitators, for example, might result in placing too much emphasis on the enjoyable part of the program and not enough on the content. The next chapter focuses on a higher level of objectives, learning objectives.

At the end of the conference, participants should rate each of the following statements 4 out of 5 on a 5-point scale:

- The meeting was organized.

- The speakers were effective.

- The meeting was valuable for business development.

- The meeting content was important to my success.

- The meeting was motivational for me personally.

- The meeting had practical content.

- The meeting contained new information.

- The meeting represented an excellent use of my time.

- I will use the material from this conference.

EXERCISE: WHAT’S WRONG WITH THESE REACTION OBJECTIVES?

Examine the objectives in Table 4.6. Under each objective, indicate what is wrong with the objective. Responses to this exercise are provided in Appendix A.

- Participants should like this program.

- The conference content will be understood by all attendees.

- Overall, participants should be satisfied at the end of the project.

- Participants should rate this workshop very stimulating as indicated by a rating of 4 on a 5-point scale.

- Participants should find that the content of this program is not too difficult.