CHAPTER 8

Creatively Eliciting and Evolving Breakthrough Requirements

A requirements elicitation workshop is one of the most effective ways to gather information quickly and arrive at consensus on complicated requirements involving a large group of stakeholders. In this chapter, we discuss best practices for both formal and informal requirements elicitation working sessions.

RUNNING POWERFUL MEETINGS

We hear complaints about poorly run meetings all the time, perhaps because meeting management skills are often undervalued and underrated in the business environment, even though meetings consume so much valuable time and so many critical resources. Why is so little effort expended to make meetings more effective? Here are a few reasons to consider, although there are likely many more:

![]() Business leaders do not recognize the relationship between ineffective meetings and organizational productivity measures.

Business leaders do not recognize the relationship between ineffective meetings and organizational productivity measures.

![]() Mid-level managers do not have the knowledge or the skills needed to plan, conduct, and facilitate an effective meeting and then follow up on decisions.

Mid-level managers do not have the knowledge or the skills needed to plan, conduct, and facilitate an effective meeting and then follow up on decisions.

![]() Project managers and business analysts do not appreciate how important good meeting planning is for achieving better, more creative results.

Project managers and business analysts do not appreciate how important good meeting planning is for achieving better, more creative results.

![]() The organization does not acknowledge that ineffective meetings are a cost drain.

The organization does not acknowledge that ineffective meetings are a cost drain.

![]() Management does not hold functional managers, business analysts, project managers, or other people accountable for the effects of ineffective meetings.

Management does not hold functional managers, business analysts, project managers, or other people accountable for the effects of ineffective meetings.

PLANNING

A great deal of planning is necessary for a requirements elicitation workshop or other type of meeting to be effectively executed. For a significant event, enlist the help of a small planning team, consisting of a co-facilitator, a scribe/modeler, and the project manager, to prepare for the event. Prior to the event, it is important to:

![]() Review all project documentation that has been produced to date, including the business case, project charter and plans, business process documentation, and supporting application system documentation.

Review all project documentation that has been produced to date, including the business case, project charter and plans, business process documentation, and supporting application system documentation.

![]() Identify the scope of the requirements to be defined in the workshop, using a context diagram.

Identify the scope of the requirements to be defined in the workshop, using a context diagram.

![]() Identify the participants needed, making sure that there will be a representative from all involved organizations and systems.

Identify the participants needed, making sure that there will be a representative from all involved organizations and systems.

![]() Ensure needed resources are available and committed to conduct elicitation activities.

Ensure needed resources are available and committed to conduct elicitation activities.

![]() Identify the goals of the workshop.

Identify the goals of the workshop.

![]() Determine the project approach, i.e., whether it will be plan driven or change driven.

Determine the project approach, i.e., whether it will be plan driven or change driven.

![]() A plan-driven approach to business analysis activities specifies all requirements up front.

A plan-driven approach to business analysis activities specifies all requirements up front.

![]() A change-driven approach to business analysis activities uses an iterative approach to requirements.

A change-driven approach to business analysis activities uses an iterative approach to requirements.

![]() Identify the artifacts to be produced during the workshop.

Identify the artifacts to be produced during the workshop.

![]() Develop a participant agenda and a facilitator agenda.

Develop a participant agenda and a facilitator agenda.

![]() Determine the approach to be used at the workshop to resolve conflicting requirements with the end users and stakeholder participants.

Determine the approach to be used at the workshop to resolve conflicting requirements with the end users and stakeholder participants.

![]() Determine the approach to be used to validate that the stated requirements resulting from the workshop meet business needs.

Determine the approach to be used to validate that the stated requirements resulting from the workshop meet business needs.

SCOPING

After all information relevant to the project has been reviewed, the planning team conducts a stakeholder analysis to determine the groups, organizations, and systems that are involved in or impacted by the project and should therefore be involved in the requirements elicitation workshop. Since the purpose of the workshop is to make key decisions about the business needs, it is important that the participants be empowered to make decisions for the organization they represent.

To identify all of the stakeholders, it is helpful to create a context diagram, which makes the scope of the requirements and players involved visible. The context diagram depicts the new or changed business system in its environment, showing all external entities that interact with the system (including people, processes, and application systems). See Figure 8-1 for a sample context diagram and Chapter 11 for additional information on conducting a robust stakeholder analysis.

FIGURE 8-1. Context Diagram Sample1

Reprinted with permission from Tilak Mitra.

PREPARING FOR A MEETING

The business analyst facilitates multiple types of meetings. Following the same basic steps for each meeting helps it to be an effective and efficient use of participants’ time and leads to a positive outcome for everyone.

ESTABLISH THE PURPOSE OF THE MEETING

Before you jump into planning a meeting, determine the objectives, purpose, and measures of success for the meeting by answering the following questions:

![]() Describe the purpose or goal of the meeting. Why have you decided to have a meeting?

Describe the purpose or goal of the meeting. Why have you decided to have a meeting?

![]() What are the objectives of the meeting?

What are the objectives of the meeting?

![]() Describe the desired outcome of the meeting. What product or deliverable will be produced or decision made that constitutes meeting success?

Describe the desired outcome of the meeting. What product or deliverable will be produced or decision made that constitutes meeting success?

![]() How will you measure the effectiveness or success of the meeting? Will the output contribute to innovation, wealth for the organization, value to the customer?

How will you measure the effectiveness or success of the meeting? Will the output contribute to innovation, wealth for the organization, value to the customer?

![]() Who needs the meeting deliverables? What exactly do they need? How will we involve them in the development and validation of the output?

Who needs the meeting deliverables? What exactly do they need? How will we involve them in the development and validation of the output?

![]() How will the meeting deliverables be used to add value to the project?

How will the meeting deliverables be used to add value to the project?

DESIGN THE MEETING TO MEET THE OBJECTIVES

Once the meeting’s purpose, objectives, and outcomes are well understood, the business analyst selects the most appropriate meeting type from among the many alternatives. Do not hold a formal meeting with a large number of participants when a small, informal working session will accomplish the meeting objectives. Keep in mind the cost of large meetings, the difficulty in reaching consensus when the group is large, and the value of small-group interactions. Everyone invited to the meeting will expect and need ample time to air their viewpoints and participate fully in the discussion and the decisions. Sometimes it is helpful to first conduct a meeting with a small group of experts and then establish a review team to comment and provide feedback on the meeting results. So think before you hold a large meeting; carefully design the meeting on the basis of the objectives, purpose of the session, and number of participants who need to support the decisions that are made. Preparations for an informal working session are likely to be less rigorous than preparations for a formal requirements elicitation workshop. But no matter how small or informal the meeting, success is directly related to adequate meeting preparation.

LEVERAGE ORGANIZATIONAL MEETING CULTURE

The organization’s meeting culture must also be considered when designing a meeting. The business analyst should take into account cultural considerations like those outlined below.

![]() Meeting tolerance. Don’t expect participants to be taken away from their business unit for meetings too often, such as more than two or three days in a week.

Meeting tolerance. Don’t expect participants to be taken away from their business unit for meetings too often, such as more than two or three days in a week.

![]() Political agendas. Conduct several meeting preparation interviews with key members of management and others who are influential within the organization to avoid political hazards. Political mistakes can be devastating to an effort to build a collaborative environment.

Political agendas. Conduct several meeting preparation interviews with key members of management and others who are influential within the organization to avoid political hazards. Political mistakes can be devastating to an effort to build a collaborative environment.

![]() Meeting history. There might be some unwritten rules about meetings. Again, conduct pre-meeting interviews to learn the meeting norms.

Meeting history. There might be some unwritten rules about meetings. Again, conduct pre-meeting interviews to learn the meeting norms.

![]() Team collaboration. Take into account the amount of collaboration and team spirit that you have been able to engender to this point. Schedule less important meetings when the group is just coming together and critical meetings after you have had a chance to work with the group and gain its trust.

Team collaboration. Take into account the amount of collaboration and team spirit that you have been able to engender to this point. Schedule less important meetings when the group is just coming together and critical meetings after you have had a chance to work with the group and gain its trust.

![]() Management structure. Be sure to respect the chain of command when considering the attendees. In addition, make sure you have management’s approval to use their resources to capture, document, and validate requirements.

Management structure. Be sure to respect the chain of command when considering the attendees. In addition, make sure you have management’s approval to use their resources to capture, document, and validate requirements.

INVOLVE KEY PARTICIPANTS EARLY

To build a collaborative environment even before a meeting, enlist key participants to assist in developing the agenda, especially the project manager, technical lead, lead business representative, and key subject matter experts. Clearly state the overall outcome to be achieved at the end of the meeting and explain any preparations the participants are expected to make before the meeting. Consultant Carter McNamara offers these tips for designing effective agendas:

![]() Include something in the agenda for participants to do right away so they come on time and get involved early.

Include something in the agenda for participants to do right away so they come on time and get involved early.

![]() Next to each major topic, note the type of action needed, the type of output expected (decision, vote, action assigned to someone), and time estimates for addressing each topic.

Next to each major topic, note the type of action needed, the type of output expected (decision, vote, action assigned to someone), and time estimates for addressing each topic.

![]() Don’t overdesign meetings; be willing to change the meeting agenda if members are making progress and are in the “creative zone.”

Don’t overdesign meetings; be willing to change the meeting agenda if members are making progress and are in the “creative zone.”

![]() Think about how you label an event so people come in with the appropriate mindset. It might pay to have a short dialogue about the meeting with key stakeholders to develop a common mindset among attendees, particularly if they include representatives from various cultures.2

Think about how you label an event so people come in with the appropriate mindset. It might pay to have a short dialogue about the meeting with key stakeholders to develop a common mindset among attendees, particularly if they include representatives from various cultures.2

SCHEDULE THE MEETING

If the meeting requires broad participation, it is likely that it will have to be scheduled far in advance so that key attendees can block out the time on their calendars. Considerations include company, organization, and department calendars, as well as individual commitments and meeting room availability.

DETERMINE THE MEETING PARTICIPANTS

Identify the appropriate people to be invited to the meeting. Ensure that they have been authorized to dedicate time to your effort and that they are empowered not only to represent their organization but also to make decisions and commitments on behalf of it. When selecting meeting participants, consider the experience level, knowledge and skills, and availability of the people you need to accomplish the meeting objectives.

Ensure that all stakeholders who will be affected by the outcome of the meeting are represented, including members of management, business unit representatives, technical experts, and virtual team members. It is almost always necessary for the business analyst to include technical representatives and the project manager in requirements sessions in which key decisions are to be made. Technical experts develop prototypes and capture graphics in real time as decisions are made, and the project manager is needed to contribute to discussions about management expectations and constraints, both time and cost.

Collaborating with others when building the meeting attendee list is a good practice. As a courtesy, try to speak with participants before they receive your meeting invitation so that they will not be surprised. This small gesture goes a long way in building trust among the team members.

PREPARE THE MEETING AGENDA AND THE FACILITATOR AGENDA

When setting the meeting agenda, the business analyst strives to strike a balance between the meeting goals and outcomes needed, the meeting process or techniques to be used, and human behaviors, the dynamics of people working together. The agenda combines a structured set of activities designed to

![]() Establish an open and safe environment

Establish an open and safe environment

![]() Transition the participants into a high-performing team

Transition the participants into a high-performing team

![]() Foster creative and critical thinking

Foster creative and critical thinking

![]() Produce work products that are innovative and will achieve the meeting objectives.

Produce work products that are innovative and will achieve the meeting objectives.

Knowing the purpose of the meeting is the first step in structuring the agenda. Having a firm idea of where you want to be by the end of the meeting suggests what must be covered during the meeting. The business analyst uses a very different set of agenda items to develop requirement functions or features than she uses to prioritize predefined requirements. Each step in reaching the desired meeting outcome is thought through carefully to determine the specific activity for that step, how it will be facilitated, and the amount of time it will take.

There are seven basic steps for developing a meeting agenda:

1. Establish how long the meeting is to last; shorter is better than longer.

2. List the agenda items that must be covered or process steps that need to occur.

3. Determine which facilitation technique to use for each agenda item. (See Chapter 7 for various facilitation models and techniques.)

4. Design the output format, which will be used as a template.

5. Build in time for key experts to be speak.

6. Estimate how long each agenda item will take, factoring in time for dialogue.

7. Leave a minimum of 15 minutes at the end for summary and agreement on what comes next.

If it is evident that more time will be needed to cover all of the agenda items than you have initially allotted, you might need to adjust the length of the meeting or cut back on what you expect to accomplish. Keep in mind that critical and creative thinking requires more time than what is typically allowed, especially if there is controversy. In addition, you need to allow more time if there is a large number of attendees so that everyone can participate. Opportunities to voice an opinion, ask questions, and explain reasons behind positions are critical to developing and achieving consensus. Taking shortcuts at this point could necessitate looping back or cause gridlock.

In the midst of making room reservations and sending out invitations, the business analyst also finalizes the facilitator agenda, which describes the tools, templates, visuals, supplies, and facilitation techniques he will use to facilitate each agenda item.

When finalizing the meeting and facilitator agendas, also consider these suggestions:

![]() Don’t start with a clean piece of paper. If the outcome of the meeting is complex, the business analyst almost always works with small groups to create a draft version of the deliverables before the meeting and then facilitates the review and refinement of the deliverables during the meeting with the larger group.

Don’t start with a clean piece of paper. If the outcome of the meeting is complex, the business analyst almost always works with small groups to create a draft version of the deliverables before the meeting and then facilitates the review and refinement of the deliverables during the meeting with the larger group.

![]() Confirm that the appropriate business and technical representatives will be available to attend the meeting and follow-up sessions. If not, the meeting should be rescheduled.

Confirm that the appropriate business and technical representatives will be available to attend the meeting and follow-up sessions. If not, the meeting should be rescheduled.

![]() For significant meetings, the business analyst invites the participants under the signature of the project or business sponsor. Attachments to the workshop invitation include a finalized agenda and summary-level project documents, which the participants should review before the meeting.

For significant meetings, the business analyst invites the participants under the signature of the project or business sponsor. Attachments to the workshop invitation include a finalized agenda and summary-level project documents, which the participants should review before the meeting.

DEFINE OUTPUTS AND DELIVERABLES

Because the business analyst designs each meeting to produce an output or a deliverable, the stakes are high. Planning an effective requirements elicitation, analysis, specification, or validation meeting requires the business analyst to prepare extensively for each event. During these preparations, the business analyst should:

![]() Determine the appropriate requirements or other artifacts to be produced as a result of the meeting, including the method, tools, and templates that will be used. (An artifact is a requirement work product, such as a document, model, prototype, table, matrix, or diagram.)

Determine the appropriate requirements or other artifacts to be produced as a result of the meeting, including the method, tools, and templates that will be used. (An artifact is a requirement work product, such as a document, model, prototype, table, matrix, or diagram.)

![]() Establish an appropriate decision process, which attendees will use to arrive at consensus on the meeting results.

Establish an appropriate decision process, which attendees will use to arrive at consensus on the meeting results.

![]() Select appropriate facilitation activities and techniques. The business analyst will use these to guide the participants in creating and verifying results.

Select appropriate facilitation activities and techniques. The business analyst will use these to guide the participants in creating and verifying results.

![]() Determine how to facilitate the interaction among meeting participants; for example, will the participants break out into small groups or work as a whole?

Determine how to facilitate the interaction among meeting participants; for example, will the participants break out into small groups or work as a whole?

![]() Determine the appropriate visual media to facilitate understanding and consensus, such as flip charts, posters, sticky notes, cards on the wall, diagrams, and other visual aids. The more visuals used, the better.

Determine the appropriate visual media to facilitate understanding and consensus, such as flip charts, posters, sticky notes, cards on the wall, diagrams, and other visual aids. The more visuals used, the better.

![]() Ensure that the participants have prepared for the meeting. Preparations might include creating straw-man work products, which can be used as a starting point for creating deliverables.

Ensure that the participants have prepared for the meeting. Preparations might include creating straw-man work products, which can be used as a starting point for creating deliverables.

SET UP THE ROOM TO FOSTER THE BEST POSSIBLE COLLABORATIVE DISCUSSIONS

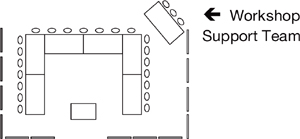

The setup of the room is important to the success of a requirements elicitation session. Arrange the room for optimal efficiency and comfort during the session. For a requirements elicitation workshop, a U-shaped setup (see Figure 8-2) is the best possible arrangement to ensure effective communication and the participation of all workshop attendees. Also see Figure 8-3, Tips for Setting Up for a Formal Workshop.

STARTING THE MEETING

Set a positive tone for the workshop and establish a collaborative environment. Always start on time. Plan something notable at the start of the meeting as an incentive to showing up on time. As an incentive, serve refreshments prior to the meeting start; this encourages everyone to arrive on time.

FIGURE 8-2. Room Setup

FIGURE 8-3. Tips for Setting Up for a Formal Workshop

SET THE STAGE

As participants arrive for the meeting, greet them by name and make introductions. Set a precedent to start the meetings on time, even if some participants have not arrived.

![]() Start by introducing yourself and describing your role as the business analyst and meeting facilitator. Also introduce other key members who helped prepare for the meeting, as well as those who will help conduct the meeting and capture the information.

Start by introducing yourself and describing your role as the business analyst and meeting facilitator. Also introduce other key members who helped prepare for the meeting, as well as those who will help conduct the meeting and capture the information.

![]() Review the agenda and discuss the goals of the meeting to get everyone prepared for the work ahead. Ask if the agenda as structured will meet everyone’s needs. If not, ask if there are any recommended adjustments to the agenda. Be prepared to accommodate the recommendations if they help achieve the meeting objectives. This secures everyone’s agreement to the agenda. You may even ask that everyone help manage the group’s time by keeping to the agenda. Emphasize the need for creativity and innovation, and state that if the group is “in the zone,” you will not interrupt or stop the meeting just to keep to the agenda.

Review the agenda and discuss the goals of the meeting to get everyone prepared for the work ahead. Ask if the agenda as structured will meet everyone’s needs. If not, ask if there are any recommended adjustments to the agenda. Be prepared to accommodate the recommendations if they help achieve the meeting objectives. This secures everyone’s agreement to the agenda. You may even ask that everyone help manage the group’s time by keeping to the agenda. Emphasize the need for creativity and innovation, and state that if the group is “in the zone,” you will not interrupt or stop the meeting just to keep to the agenda.

![]() Review the project objectives in business terms, relate the meeting to the project objectives, and briefly discuss follow-on activities that are expected.

Review the project objectives in business terms, relate the meeting to the project objectives, and briefly discuss follow-on activities that are expected.

CONDUCT AN ICEBREAKER

If it is the first meeting of the group, plan a warm-up activity that helps the team members test their voices and get to know each other. Use an icebreaker to relax meeting participants, introduce them to each other, and energize the start of a meeting. Resist the temptation to use games as icebreakers. This may turn off some of your participants before you get a chance to engage them. Effective types of icebreakers include:

![]() Asking each participant to introduce themselves and provide answers to predefined questions

Asking each participant to introduce themselves and provide answers to predefined questions

![]() Individual or group activities, such as determining a group name.

Individual or group activities, such as determining a group name.

![]() Pairing the group and asking partners to exchange ideas on a relevant topic.

Pairing the group and asking partners to exchange ideas on a relevant topic.

ESTABLISH GROUND RULES FOR THE MEETING

Ground rules are operating standards that determine how people conduct discussions and make decisions. At the beginning of the meeting, the business analyst should facilitate a discussion on ground rules, allowing the group to formulate its own operating standards. The facilitator might ask, “What team operating agreements should we adopt to make our work more efficient and of higher quality?” Or, simply, “What are some important guidelines we should all keep in mind as we work together in this and future meetings?” Use the multi-vote technique to gain approval of the rules if there are too many to deal with effectively. The group should review and revise the ground rules as needed.

Figure 8-4 presents typical ground rules.

CAPTURE AND SET EXPECTATIONS

The purpose of setting expectations is to uncover the participants’ expectations and ensure they align with the objectives of the workshop. During this activity:

![]() Document expectations on a flip chart.

Document expectations on a flip chart.

![]() Address expectations that are not aligned with the meeting purpose and objectives; perhaps write them on a flip chart for future actions.

Address expectations that are not aligned with the meeting purpose and objectives; perhaps write them on a flip chart for future actions.

![]() Reference the expectations throughout the meeting to validate meeting progress.

Reference the expectations throughout the meeting to validate meeting progress.

Setting expectations for the workshop is important for moving forward smoothly with the session. In the overview early in the meeting, the business analyst should state clearly what will be accomplished during the workshop and what will be left for other sessions. The business analyst also provides a brief overview of the requirements elicitation process to be used during the session.

FIGURE 8-4. Meeting Ground Rules

![]() Briefly, and in general terms, review the requirements elicitation process that will be followed. Set clear expectations for the workshop deliverables and closeout activities that need to be completed after the workshop.

Briefly, and in general terms, review the requirements elicitation process that will be followed. Set clear expectations for the workshop deliverables and closeout activities that need to be completed after the workshop.

![]() Announce that the expectations that were captured at the beginning of the session will be reviewed at the end. If some have not been met, note an action item to make sure that these expectations are met at a later time. If it is obvious that some of the stated expectations cannot be covered in the session, discuss them very briefly, explain why they are out of scope for the session, and indicate how they will be addressed.

Announce that the expectations that were captured at the beginning of the session will be reviewed at the end. If some have not been met, note an action item to make sure that these expectations are met at a later time. If it is obvious that some of the stated expectations cannot be covered in the session, discuss them very briefly, explain why they are out of scope for the session, and indicate how they will be addressed.

![]() You may need to conduct brief training sessions for activities that will be conducted that participants are not familiar with.

You may need to conduct brief training sessions for activities that will be conducted that participants are not familiar with.

FACILITATING THE MEETING

Facilitators model and enable effective group interactions. They set the standards for group exchanges, listening carefully, directing and redirecting the discussion, and ensuring all participants are engaged and are contributing to the discussion. The best facilitators are relaxed, use humor to make others feel comfortable, and make sure group sessions are enjoyable.

One common pitfall is to plan too much for the time allowed. Following the facilitator agenda will go a long way in preventing this occurrence. Always remain flexible and plan for activities to take longer than you think they will. Constantly evaluate how the session is going, gauging energy levels and watching group behaviors and body language.

To lead your participants into the “creative zone,” encourage both critical and creative thinking. Each requires a different mindset and leads to different outcomes. According to Teacher Tap, a free professional development resource:

![]() Critical thinking involves logical thinking and reasoning, including techniques such as comparison, classification, sequencing, cause/effect, patterning, webbing, analogies, deductive and inductive reasoning, forecasting, planning, hypothesizing, and critiquing.

Critical thinking involves logical thinking and reasoning, including techniques such as comparison, classification, sequencing, cause/effect, patterning, webbing, analogies, deductive and inductive reasoning, forecasting, planning, hypothesizing, and critiquing.

![]() Creative thinking involves creating something new or original. It involves the flexibility, originality, fluency, elaboration, brainstorming, modification, imagery, associative thinking, attribute listing, metaphorical thinking, and forced relationships. The aim of creative thinking is to stimulate curiosity and promote divergence.3

Creative thinking involves creating something new or original. It involves the flexibility, originality, fluency, elaboration, brainstorming, modification, imagery, associative thinking, attribute listing, metaphorical thinking, and forced relationships. The aim of creative thinking is to stimulate curiosity and promote divergence.3

Always maintain control of your meetings. If you invite a member of senior management to kick off a meeting, he may “get on a roll” and take much more time than allotted. You may avoid this by preparing your guest for the situation: list the key points you would like him to cover and tell him how much time you have allotted for his brief remarks and a few questions that will likely follow.

When you open any meeting or presentation to group participation, there is a risk of losing control. If you think a question or comment is not relevant, say so, but try hard to be patient with those who take the discussion off track. You might say, “Actually, that comment isn’t within the scope of our discussion today.”

To help the team stick to the agenda, consider the following time-management techniques:

![]() Parking lot. Use a flipchart labeled “Parking Lot” to list ideas that come up during discussion but are outside the scope of the meeting. Ask the individual who brought up the item for permission to “park” the item until the end of the session. At the end of the session, disposition the items by scheduling another meeting with the appropriate participants, putting the “parked” items on a list of action items or issue log, and assigning ownership and a due date to each item. Ask those whose ideas have been “parked” if they are satisfied with the follow-up plan.

Parking lot. Use a flipchart labeled “Parking Lot” to list ideas that come up during discussion but are outside the scope of the meeting. Ask the individual who brought up the item for permission to “park” the item until the end of the session. At the end of the session, disposition the items by scheduling another meeting with the appropriate participants, putting the “parked” items on a list of action items or issue log, and assigning ownership and a due date to each item. Ask those whose ideas have been “parked” if they are satisfied with the follow-up plan.

![]() Refocusing questions. If the discussion begins to digress, take a moment to reword and refocus the question that is under consideration. This can often put the group back on track.

Refocusing questions. If the discussion begins to digress, take a moment to reword and refocus the question that is under consideration. This can often put the group back on track.

![]() Timekeeping. Use the power of the agenda to keep the meeting on track. If an item is going over the allotted time but very valuable discussions are taking place, do not stop the meeting. At a breaking point, note that the time has been exceeded, and arrive at a consensus on how to use the remaining time and reschedule items that have not been covered.

Timekeeping. Use the power of the agenda to keep the meeting on track. If an item is going over the allotted time but very valuable discussions are taking place, do not stop the meeting. At a breaking point, note that the time has been exceeded, and arrive at a consensus on how to use the remaining time and reschedule items that have not been covered.

![]() Placement. Place high-priority topics that require rigorous discussion and interaction at the very beginning of the agenda to ensure they get the time and attention they need, and allow flexibility in the agenda if more time is needed.

Placement. Place high-priority topics that require rigorous discussion and interaction at the very beginning of the agenda to ensure they get the time and attention they need, and allow flexibility in the agenda if more time is needed.

FACILITATING VIRTUAL MEETINGS

In this borderless world, there is no getting around it: business analysts will be called upon to facilitate multisite teams. Special facilitation approaches are needed when facilitating teleconference, video-teleconference, and web meetings. All meetings require supporting materials, such as the agenda and other documentation relevant to agenda items. Many virtual teams rely heavily on paper-based communication to ensure that everyone is fully informed and working from the same information. The materials should be as visual as possible so that everyone sees the same picture and is talking about the same concept.

For important training, elicitation, or validation sessions, a very effective approach is to have a lead facilitator and an onsite facilitator at each location, all directing the discussions at their respective venue. The facilitators collaborate beforehand to establish detailed plans and to design the event. They test for meeting effectiveness by polling participants during and at the end of the meeting and incorporate the suggestions into future sessions.

TOOLS FOR PROCESS IMPROVEMENT SESSIONS

When determining requirements for a business process improvement project, process improvement tools create a common vision for improving business results. While facilitating process improvement sessions, consider using a process map, flow chart, or process chart. To focus everyone on the scope of the process under review, offer an early draft of the process map, flow chart, or process chart before the meeting. Throughout the requirements-gathering sessions, challenge the group to innovate by asking questions like, Are we making breakthrough changes that will result in increased value to our customers and/or our organization? Or is this pretty much business as usual?

PROCESS MAP

A process map shows how specific work gets done in an organization. It is also referred to as a swim lane diagram (Figure 8-5). Each box in the diagram represents a step in the process, and a textual definition for each box or step is usually included along with the diagram.

FLOW CHART

A flow chart is a graphic representation of the sequence of steps to be followed to execute a process.

PROCESS CHART

A process chart is a tool to help teams manage, improve, and control processes.

TOOLS FOR ANALYSIS SESSIONS

Analysis facilitation tools are used to identify and study factors when improving and making organizational changes. Again, the facilitator should be sure to encourage creative and critical thinking, as opposed to business as usual.

PROBLEM AND OPPORTUNITY ANALYSIS

In our rush to results, sometimes groups come up with great solutions for the wrong problem. Prior to problem solving, be certain you truly understand the problem by following these steps:

1. Document the problem in detail.

2. Determine the adverse effects the problem is causing.

3. Determine how soon the problem must be solved and the cost of doing nothing.

4. Conduct root cause analysis to determine the underlying source of the issues.

5. Determine the kinds of analysis required to address the issues.

6. Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for a solution.

ROOT CAUSE ANALYSIS

A root cause diagram (also called a cause-and-effect or fishbone diagram) is used to identify and organize the actual causes of a problem. It is like a map that depicts possible cause-and-effect relationships. It helps groups organize ideas for further analysis.

There are six steps to developing a root cause diagram:

1. Write the issue or problem under discussion in a box at the top of the diagram.

2. Draw a line from the box across the paper or white board (this forms the spine of the fishbone).

3. Draw diagonal lines from the spine to represent categories of potential causes of the problem. Categories may include people, processes, tools, and policies. Don’t label the lines yet.

4. Draw smaller lines extending from the diagonal lines to represent specific causes in each category; again, don’t label these lines yet.

5. Brainstorm relevant categories and potential causes of the problem, label each diagonal line with a category, and note the specific causes under the appropriate category.

6. Analyze the results. Remember, the group has only identified potential causes of the problem. Further analysis, ideally with data, is needed to validate the actual cause or causes.

Once the actual cause or causes have been identified, the group brainstorms potential solutions, either in the same or a follow-on session.

STORYBOARD ANALYSIS

A storyboard is a visualization tool that graphically organizes process steps in sequence (see Figure 8-6). A storyboard can be used:

![]() As an accompaniment to a project proposal, to show how a project to develop a new business solution will look

As an accompaniment to a project proposal, to show how a project to develop a new business solution will look

![]() To depict how a business process will function

To depict how a business process will function

![]() To describe the steps in a process, using one box for each major activity.

To describe the steps in a process, using one box for each major activity.

FIGURE 8-6. Sample Storyboard

FIGURE 8-7. Gap Analysis Template

GAP ANALYSIS

A gap analysis is a tool used to compare actual performance with desired performance. It answers two questions: “Where are we?” and “Where do we want to be?” Figure 8-7 is a simple template for a gap analysis. Gap analysis can be used to:

![]() Benchmark or otherwise assess general expectations of performance in industry, compared with current organizational capabilities.

Benchmark or otherwise assess general expectations of performance in industry, compared with current organizational capabilities.

![]() Determine, document, and evaluate the variance or distance between a current and desired future business process.

Determine, document, and evaluate the variance or distance between a current and desired future business process.

![]() Determine, document, and approve the variance between business requirements and system capabilities in terms of COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) packaged application features (this is also referred to as a deficiency assessment).

Determine, document, and approve the variance between business requirements and system capabilities in terms of COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) packaged application features (this is also referred to as a deficiency assessment).

![]() Discover discrepancies between two or more sets of diagrams.

Discover discrepancies between two or more sets of diagrams.

![]() Analyze the gap between requirements that are met and not met (this also can be called a deficiency assessment).

Analyze the gap between requirements that are met and not met (this also can be called a deficiency assessment).

![]() Compare actual performance against potential performance and then determine the areas in which improvement must be achieved.

Compare actual performance against potential performance and then determine the areas in which improvement must be achieved.

FIGURE 8-8. SWOT Analysis Template

SWOT ANALYSIS

A SWOT—strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats—analysis is used to capture aspects of the current state of the business as a whole, or a specific line of business or business process that is undergoing change (see Figure 8-8). Be sure to focus the discussion on creative opportunities and ways to leverage strengths.

IMPACT ANALYSIS

An impact analysis is a process to determine the costs and benefits, or other competing demands, of a proposed alternative (see Figure 8-9). Each letter represents one of the options under consideration.

FIGURE 8-9. Impact Analysis Template

FIGURE 8-10. Force Field Analysis Template

FORCE FIELD ANALYSIS

A force field analysis is a problem-solving technique used to identify and address driving and restraining factors when making an organizational change (see Figure 8-10). Driving forces help the option succeed, while restraining forces pose barriers to the success of the option.

QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSIONS

Question and answer (Q&A) sessions are used to assess understanding and validate consensus. There are two types of questions: closed and open. A closed question is usually used to check participants’ comprehension. It requires a factual answer and allows little opportunity for dissent. The answer will be either correct or incorrect. An open, or higher-order, question offers participants much more opportunity to speculate, draw inferences, extrapolate from data, or contribute their own opinions. Open questions are frequently used as springboards for lively discussion, so learn to use open questions liberally. It is a good idea to think of some possible answers to an open question before you ask it to ensure you are eliciting the correct thought process.4

ASKING QUESTIONS

![]() Be sure to ask only one question at a time.

Be sure to ask only one question at a time.

![]() Give the group time for deliberation. Wait 10–15 seconds for a response.

Give the group time for deliberation. Wait 10–15 seconds for a response.

![]() If there is no answer, rephrase the question and ask it again. Jumping to a different topic may cause confusion.

If there is no answer, rephrase the question and ask it again. Jumping to a different topic may cause confusion.

![]() If there is still no answer, you have just discovered that no one in the room has the requisite expertise to provide the background and information needed to move on. You may need to adjourn the meeting and reconvene after conducting research or when experts are available to join the discussion.

If there is still no answer, you have just discovered that no one in the room has the requisite expertise to provide the background and information needed to move on. You may need to adjourn the meeting and reconvene after conducting research or when experts are available to join the discussion.

ANSWERING QUESTIONS

In his article, “Question and Answer Session after the Presentation,” Dr. Stephen D. Boyd, a professor of speech communication, offers the following guidelines:

![]() Answering participants’ questions can be unnerving at first. If you do not know the answer, say so and put it in the “parking lot” so you will remember to find the answer later. It is better to be honest than to give an inaccurate answer that will have to be retracted later. Tell the participants you will answer the question by the next meeting; better still, invite the questioner to find the answer and report it at the next meeting.

Answering participants’ questions can be unnerving at first. If you do not know the answer, say so and put it in the “parking lot” so you will remember to find the answer later. It is better to be honest than to give an inaccurate answer that will have to be retracted later. Tell the participants you will answer the question by the next meeting; better still, invite the questioner to find the answer and report it at the next meeting.

![]() Listen to questions carefully. Some questions may indicate that a participant is having difficulty with the concepts being discussed. You may wish to answer with another question until you discover where the questioner’s misunderstanding begins.

Listen to questions carefully. Some questions may indicate that a participant is having difficulty with the concepts being discussed. You may wish to answer with another question until you discover where the questioner’s misunderstanding begins.

![]() If a question requires a very lengthy response or indicates that the questioner has missed some meetings, you may wish to ask the participant to stay behind after the meeting or come see you at another time to get the answer.

If a question requires a very lengthy response or indicates that the questioner has missed some meetings, you may wish to ask the participant to stay behind after the meeting or come see you at another time to get the answer.

![]() Invite questions by saying, “Who has the first question?” Look expectant after you ask the question. If no one asks a question, engage the group and encourage discussion by saying something like, “A question I’m often asked is.…” You may answer the question you posed or see if anyone would like to attempt a response. If there are still no questions, you can finish with “Are there any other questions?”

Invite questions by saying, “Who has the first question?” Look expectant after you ask the question. If no one asks a question, engage the group and encourage discussion by saying something like, “A question I’m often asked is.…” You may answer the question you posed or see if anyone would like to attempt a response. If there are still no questions, you can finish with “Are there any other questions?”

![]() Always repeat the question before you begin to respond to ensure you understand the intent. This is essential if there is a large audience; it also helps if you need a moment to think. Look at the entire audience when responding, and then look at the questioner as you complete your response to see if it was adequate.

Always repeat the question before you begin to respond to ensure you understand the intent. This is essential if there is a large audience; it also helps if you need a moment to think. Look at the entire audience when responding, and then look at the questioner as you complete your response to see if it was adequate.

![]() Stand in a place where you are equally distant from all members of your audience.

Stand in a place where you are equally distant from all members of your audience.

![]() Be concise; don’t let your response turn into a presentation.

Be concise; don’t let your response turn into a presentation.

![]() Don’t answer a loaded question designed to throw you off guard. Before answering, say something like, “I sense your frustration with … and I think you are asking.…” Then answer that question. If the questioner is not satisfied, invite her to meet with you after the session.

Don’t answer a loaded question designed to throw you off guard. Before answering, say something like, “I sense your frustration with … and I think you are asking.…” Then answer that question. If the questioner is not satisfied, invite her to meet with you after the session.

![]() Manage comments that are not questions. Do not allow anyone to hijack the Q&A session. When the speaker pauses to take a breath or regroup, thank him for his comment and move to a questioner on the other side of the room.

Manage comments that are not questions. Do not allow anyone to hijack the Q&A session. When the speaker pauses to take a breath or regroup, thank him for his comment and move to a questioner on the other side of the room.

![]() Don’t say, “That was a great question.” You can’t say it for every question, and others will think their question was not so good. You could say, “Thanks for asking that question.”5

Don’t say, “That was a great question.” You can’t say it for every question, and others will think their question was not so good. You could say, “Thanks for asking that question.”5

EVALUATING THE MEETING

It is important to evaluate a meeting early and often. Get participant feedback during the meeting when you can improve the meeting in process immediately. (Evaluating a meeting only at the end will usually only help future meetings.) At key points during the meeting, informally ask what is working well and what can be improved in the conduct of the meeting. Be prepared to incorporate improvements immediately.

At the end of the meeting, allow five to ten minutes to evaluate the session. This evaluation should focus on how the group did as a whole working together, not on your performance as the facilitator. Go around the room and ask each participant to rate the meeting from 1–7, with a rating of 1 meaning that the participant thought it was a waste of time, and a rating of 7 meaning that the meeting far exceeded the participant’s expectations. (Use the same scale each time so that you can determine if participants’ satisfaction is increasing as the group gels.) Next, ask each participant what he or she liked most about the group’s work, and what opportunities he or she sees to improve either team interactions or the quality of the output in future meetings (participants can pass if they do not have a comment). Always have the senior person in the room evaluate the meeting last. Be sure to incorporate suggestions into future events. In that way you are continually improving the ability of the group to work together toward common goals.

CLOSING THE MEETING

Always end meetings on time. It is also important to end a meeting on a positive note. Typical meeting wrap-up steps include:

![]() Issues and action items. Review action items, issues, and unmet expectations. Assign an owner and due date for each action item and issue. Explain that the owner of each issue is charged with enlisting the help of a small team of experts to discuss the issue, identify alternatives for resolution of the issue, conduct a feasibility analysis of each alternative, and propose the most feasible (and most innovative) resolution to the group at the next meeting.

Issues and action items. Review action items, issues, and unmet expectations. Assign an owner and due date for each action item and issue. Explain that the owner of each issue is charged with enlisting the help of a small team of experts to discuss the issue, identify alternatives for resolution of the issue, conduct a feasibility analysis of each alternative, and propose the most feasible (and most innovative) resolution to the group at the next meeting.

![]() Next meeting. Set the date, time, and main agenda items for the next meeting.

Next meeting. Set the date, time, and main agenda items for the next meeting.

![]() Next steps. Ask that the meeting outputs, including all requirements artifacts, minutes, and the issue/action logs, be reported back to participants within one week; this is important to keep the momentum.

Next steps. Ask that the meeting outputs, including all requirements artifacts, minutes, and the issue/action logs, be reported back to participants within one week; this is important to keep the momentum.

![]() Meeting evaluation. Evaluate the success of the event, meaning how well the group worked together and the quality of the outputs, as described earlier.

Meeting evaluation. Evaluate the success of the event, meaning how well the group worked together and the quality of the outputs, as described earlier.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: WHAT DOES THIS MEAN TO THE BUSINESS ANALYST?

Regardless of the meeting facilitation approach you use, following these guidelines will go a long way toward improving your facilitation skills:

![]() Use humor, stories, and examples that directly relate to the work of the group.

Use humor, stories, and examples that directly relate to the work of the group.

![]() Evaluate how the session is going after each major agenda item and at the end of the day; incorporate feedback into the next part of the session and future events.

Evaluate how the session is going after each major agenda item and at the end of the day; incorporate feedback into the next part of the session and future events.

![]() Use lots of visual tools to keep everyone engaged and on the same page.

Use lots of visual tools to keep everyone engaged and on the same page.

And avoid these common pitfalls:

![]() Pushing toward a preconceived “right” answer; there is no right answer.

Pushing toward a preconceived “right” answer; there is no right answer.

![]() Appearing to be dominating; ignoring a participant’s suggestion.

Appearing to be dominating; ignoring a participant’s suggestion.

![]() Reading from a document or delivering a lengthy presentation.

Reading from a document or delivering a lengthy presentation.

![]() Favoring one group’s perspective.

Favoring one group’s perspective.

As you plan and conduct your workshops and working sessions, always remember that requirements elicitation is an iterative process. Although it is imperative to capture, continually refine, and validate requirements using visualization techniques whenever possible, textual descriptions are also needed for clarity and to precisely describe technical requirements. Visual graphs and diagrams are necessary to depict sequences and dependencies.

Remember, requirements alone are not complex; it is the interrelationships and interdependencies among requirements that impose complexities that are difficult to understand, and the impacts of which are difficult to predict.

NOTES

1. Tilak Mitra, “Figure 1: System context diagram,” May 13, 2008. Online at http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/ar-archdoc2/index.html?S_TACT=105AGX20&S_CMP=EDU (accessed April 2011).

2. Carter McNamara, “Basic Guide to Conducting Effective Meetings,” Free Management Library (undated). Online at http://www.managementhelp.org/misc/mtgmgmnt.htm (accessed February 2011).

3. Larry Johnson and Annette Lamb, “Critical and Creative Thinking—Bloom’s Taxonomy,” Teacher Tap (2011). Online at http://eduscapes.com/tap/topic69.htm (accessed February 2011).

4. Dalhousie University Center for Learning and Teaching, “Question and Answer Techniques,” (undated). Online at http://learningandteaching.dal.ca/taguide/QandATechniques.htm (accessed February 2011).

5. Stephen D. Boyd, “Question and Answer Session after the Presentation,” Ron Kurtus’ School for Champions (2011). Online at http://www.school-for-champions.com/speaking/boyd_q_a_after_pres.htm (accessed February 2011). Copyright © 2011 by Ron Kurtus and School for Champions LLC.