CHAPTER 2

The Business Analyst’s Strategic Role

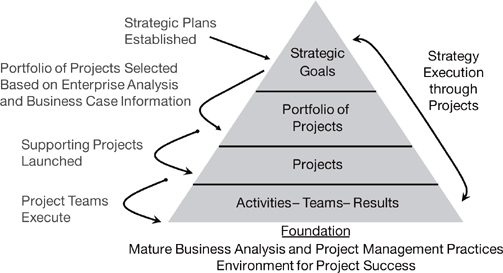

The business analyst is a key participant in strategic activities, working to inform decision makers to ensure that the organization invests in the most valuable projects as well as tactical project-focused activities once a project is funded. In this chapter, we first discuss the business analyst’s role in strategic planning and enterprise analysis. We then present the business analyst’s role in activities intended to define and manage business requirements and to continuously validate that the solution will meet business needs: planning, elicitation, requirements analysis, specification, documentation, solution assessment and validation, change management, solution delivery, cultural change management, and solution maintenance and enhancement. Figure 2-1 illustrates the BA’s roles and responsibilities on projects.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

Strategic planning is not typically thought of as a project phase. It is, however, the first set of activities in a business project’s life. During strategic planning, the leadership team examines the current state of an enterprise and determines the desired future state by describing a set of broad goals.

FIGURE 2-1. The BA Role in Projects

© 2011 by Kathleen B. Hass and Associates, Inc.

The business architect, an emerging position, is charged with developing a complete set of documentation that depicts the current state of the business so that everyone has a consistent, accurate understanding of the business. The business architect also documents the future state of the business—how it will look when the strategy has been achieved—so that everyone has a common understanding of the future state of the business. Enterprise analysts (often called strategy analysts, portfolio managers, business planners, or business/technology analysts, among other titles) then identify gaps in capabilities needed to achieve the future state and conduct enterprise analysis, converting the future strategy to measurable objectives to close the gaps.

A STRATEGY-EXECUTION FRAMEWORK

Many organizations struggle or even fail to execute their strategy, even when it is well formed. The reason most often given for this failure is that executives do not think they have a framework for strategy execution. That framework is called portfolio management. The decisions made during the strategic planning and goal-setting process drive portfolio management, the critical business practice embedded between strategic planning and project execution in which projects are selected, prioritized, and funded, thus converting strategic goals into actionable objectives, scope, and approach.

CAREER ADVICE

Business Enterprise Analysts

Less than one-fifth of companies have effective portfolio management practices. Enterprise analysts are needed to prepare high-quality business cases to provide management with sound decision-support information.

A Word to the Wise

Business architects and enterprise business analysts are emerging to fill the gap in enterprise analysis and creative leadership.

Muster the courage to jump into high-level strategic roles.

If your project does not have a business case, gather a small expert team and guide them through the steps to create one.

Present the business case to the sponsor for review/approval.

Update the business case throughout the project to validate that continued investment in the project is warranted. If not, propose a course correction to the project manager and the sponsor.

As enterprise analysts become more common in organizations, they will be called upon to conduct feasibility analysis, competitive analysis, opportunity analysis, problem analysis, financial analysis, and benchmark studies and to devise innovative recommendations to provide the senior team with the information needed to forge the optimal future vision and to convert innovative ideas into a business case, which serves as a new project proposal in the portfolio management process.

In today’s world, the strategic plan is considered a living, breathing road map that changes and evolves with changes in the dynamic and often chaotic marketplace. As the strategies change, the portfolio of programs and projects must also change. Therefore, organizations need to be able to make changes to their project portfolio quickly and effectively.

THE CORPORATE SCORECARD

Scores of broad, important goals are likely to be developed during the strategic planning cycle. Strategic goals are then converted into an organized, actionable, measurable set of portfolios to attain the intended results. There needs to be a simple approach to tracking progress toward achieving the strategy. To monitor the journey, executive teams are building corporate scorecards as an outgrowth of their strategic plans. Increasing the wealth of stakeholders is the ultimate goal of for-profit organizations; as a result, financial goals often rank highest. However, nonfinancial decision criteria are also needed; these represent investments in the future health of the enterprise. A specific model, called the balanced scorecard, provides an effective tool to frame strategic goals.1 In this model, goals are partitioned into four dimensions: financial, customer, internal operations, and learning and innovation, as described below.

![]() Financial goals are the quantitative goals that address the business’s finance and accounting outcomes. Example: “Earn 6 percent on sales, 18 percent on investments, and 12 percent on assets this year.”

Financial goals are the quantitative goals that address the business’s finance and accounting outcomes. Example: “Earn 6 percent on sales, 18 percent on investments, and 12 percent on assets this year.”

![]() The primary measure of customer goals is customer satisfaction. Example: “Earn a customer satisfaction rating of 95 percent or better this year.”

The primary measure of customer goals is customer satisfaction. Example: “Earn a customer satisfaction rating of 95 percent or better this year.”

![]() Internal operations goals relate to process and operational performance and the effectiveness of core competencies. Measures are typically internal, comparing performance with industry benchmarks. Example: “Achieve inventory turns of 8.0 or better this year.”

Internal operations goals relate to process and operational performance and the effectiveness of core competencies. Measures are typically internal, comparing performance with industry benchmarks. Example: “Achieve inventory turns of 8.0 or better this year.”

![]() Learning and innovation goals address new product development, organizational learning and skill development, and application of technology and productivity tools. Example: “Increase revenue by 50 percent through new products and services.”

Learning and innovation goals address new product development, organizational learning and skill development, and application of technology and productivity tools. Example: “Increase revenue by 50 percent through new products and services.”

Mission results drive agencies in the public sector and nonprofit organizations, so strategic goals take on a slightly different slant. Measures are established to answer the following questions.

![]() Customer: “How do our customers view our effectiveness?”

Customer: “How do our customers view our effectiveness?”

![]() Financial: “Are our solutions the most cost-effective ones?”

Financial: “Are our solutions the most cost-effective ones?”

![]() Internal processes: “Are our business processes effective and efficient?”

Internal processes: “Are our business processes effective and efficient?”

![]() Innovation and improvement: “How do we continue to improve and create value for our customers?”

Innovation and improvement: “How do we continue to improve and create value for our customers?”

ITERATIVE PLANNING CYCLES

Today the stakes are so high and the environment is so volatile that attention must be rigorously focused on evolving the organization’s strategy, goals, and resulting change initiatives. Just as the strategic plan is a living document, strategic goals and objectives also are dynamic, so the planning process includes iterative planning cycles to monitor progress and make course corrections along the way. The bar for adding business value is raised for every planning cycle. As always, the executive management team is ultimately accountable for setting the right strategies for the success of the organization. However, they need accurate information, analysis of business problems and opportunities, creative ideas, and innovative approaches provided by seasoned business analysts who are experts in the relevant lines of business and in the technology that not only supports but optimizes the business results.

ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS

Enterprise analysis should not be thought of as a phase, but as a series of activities that are performed iteratively throughout the life of a project. In more mature organizations, a significant amount of enterprise analysis occurs to support strategy development. After the business architect depicts the future view of the business, the enterprise analyst conceptualizes creative new business solutions to seize new opportunities and therefore execute strategy. At this point, the business analyst demonstrates the leadership and creativity needed for the organization to remain competitive through the enterprise analysis activities described below. In practice, enterprise analysis is too often short changed—or worse omitted altogether.

ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS ACTIVITIES

The core enterprise analysis activities center on (1) identifying new business opportunities or solutions to business problems; (2) conducting studies, gathering information, brainstorming, innovating, and creating to determine the most feasible solution alternatives; and (3) developing a business case or project proposal document to recommend a new project to management, which will then decide whether to select, prioritize, and fund the change initiative. If the initiative is selected, a new project is formed and the planning and requirements activities of the project begin.

CAREER ADVICE

Business Enterprise Analysts

All too often, enterprise analysis activities are misunderstood, undervalued, not budgeted for, and skipped altogether. Absent real enterprise analysis, organizations are:

Unable to ensure they are invested in the most valuable projects.

Unsure of the value of their project portfolio.

Missing valid business objectives that describe the expected value to the customer and project revenue anticipated from the organization’s funded projects.

A Word to the Wise

Work with the line of business executives, the most influential managers, and senior project managers to inform them about the strategic value of enterprise analysis activities culminating in a sound business case. Bring together a small expert team and guide them through the enterprise analysis activities.

Enterprise analysis activities are carried on by the business analyst throughout the project to continually validate that the business need is understood, it has not changed, and the emerging solution will meet the need. The enterprise analysis activities even continue after the project has been completed and the enterprise has experienced, measured, and analyzed the benefits of the initiative.

FIGURE 2-2. Organizational Strategic Alignment

An organization’s ability to achieve goals through projects depends on its ability to select the most valuable projects and then execute them flawlessly. Organizational strategic alignment is achieved when strategic plans and goals are converted into a portfolio of programs and supporting projects. Strategic project leaders and project teams execute the project plans to meet objectives and deliver project outcomes, thus adding value to the enterprise (see Figure 2-2).

ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS IN PRACTICE

Business architects and enterprise business analysts play a significant role in translating business strategies into innovative new business change initiatives through enterprise analysis activities: analyzing the enterprise and the competitive environment and experimenting and brainstorming to identify the most creative solution. During these early discovery and definition activities, requirements are determined and documented at a very high level. Initial requirements definition originates early, when the product concept is first envisioned. The business architect documents the current and future states of the enterprise. Then the enterprise analyst works with a small team of experts to conduct creative sessions to identify the most feasible, innovative, lucrative approach and to document the results for all to see. The requirements for new business opportunities, the alternatives considered, and the approach to be proposed are captured in some kind of initiating document, called the business case, project charter, or statement of work. All requirements should be traceable to these original sources.

The array of enterprise analysis activities, which are guided by the business analyst and are described in Chapter 5 of the BABOK® Guide,2 are listed below for your convenience. Organizations use some or all of these techniques, depending on the maturity of their business analysis practices. These activities appear to be sequential, but they are usually conducted concurrently and iteratively.

![]() Creating and maintaining the business architecture. The business architecture is the set of artifacts that comprise the attributes and characteristics of the business. It is a compilation of interrelated elements that depict information about the business: its operations, organizational structures and physical locations, the boundary of business processes, business rules, policies and procedures, and the lines of business used to flow value through to customers.

Creating and maintaining the business architecture. The business architecture is the set of artifacts that comprise the attributes and characteristics of the business. It is a compilation of interrelated elements that depict information about the business: its operations, organizational structures and physical locations, the boundary of business processes, business rules, policies and procedures, and the lines of business used to flow value through to customers.

![]() Conducting feasibility, benchmark, and competitive analysis studies. A feasibility study is an evaluation conducted to determine if a business opportunity idea is achievable within cost, schedule, or other limitations. A benchmark study is a review of what best-of-breed organizations (often competitors) are doing to achieve their level of superior performance, so that the organization can try to replicate them. This study may also involve a comparison of performance between a new proposed product versus an existing product, system, or system component.

Conducting feasibility, benchmark, and competitive analysis studies. A feasibility study is an evaluation conducted to determine if a business opportunity idea is achievable within cost, schedule, or other limitations. A benchmark study is a review of what best-of-breed organizations (often competitors) are doing to achieve their level of superior performance, so that the organization can try to replicate them. This study may also involve a comparison of performance between a new proposed product versus an existing product, system, or system component.

![]() A competitive analysis study is an evaluation of the competition in the marketplace, including past, current, and projected performance, to help the organization establish future plans to remain competitive.

A competitive analysis study is an evaluation of the competition in the marketplace, including past, current, and projected performance, to help the organization establish future plans to remain competitive.

![]() Identifying new business opportunities. As an outgrowth of strategic planning, the enterprise analyst reviews the results of feasibility, benchmark, and competitive analysis studies and the future business architecture to identify potential solution options for achieving strategic goals. The enterprise business analyst works with an expert team to identify new business opportunities and conduct trade-off analysis to determine the most viable option. The goal is to select a solution that will provide the most positive (valuable) outcome the fastest and that poses the least risk to the enterprise.

Identifying new business opportunities. As an outgrowth of strategic planning, the enterprise analyst reviews the results of feasibility, benchmark, and competitive analysis studies and the future business architecture to identify potential solution options for achieving strategic goals. The enterprise business analyst works with an expert team to identify new business opportunities and conduct trade-off analysis to determine the most viable option. The goal is to select a solution that will provide the most positive (valuable) outcome the fastest and that poses the least risk to the enterprise.

![]() Scoping and defining new business opportunities. Once the team has chosen the best alternative for achieving business goals, the solution must be defined to the level of detail the portfolio planning team considers necessary for deciding whether to invest in the change initiative. This is a challenging task for the business analyst because the organization does not want to make a significant investment in an idea that may not survive the project selection and prioritization process. So the business analyst works again with a team of subject matter experts to compile just enough information to determine if the proposed solution is viable.

Scoping and defining new business opportunities. Once the team has chosen the best alternative for achieving business goals, the solution must be defined to the level of detail the portfolio planning team considers necessary for deciding whether to invest in the change initiative. This is a challenging task for the business analyst because the organization does not want to make a significant investment in an idea that may not survive the project selection and prioritization process. So the business analyst works again with a team of subject matter experts to compile just enough information to determine if the proposed solution is viable.

![]() Preparing the business case. A business case should be developed for all significant change initiatives and capital projects, including major IT projects. Business unit managers may take the lead in developing business cases for projects that benefit their departments. However, many projects cross business units, and the talents of a senior business analyst facilitate the difficult decisions that must be made to satisfy the often competing demands of all areas impacted by the change. The business analyst brings key experts together to gain agreement on the initiative. Accurately predicting the costs and benefits of major initiatives is a critical skill that requires the combined disciplines of business analysis, project management, and IT expertise to estimate the costs of software development and technology acquisition, as well as business prowess to predict the business costs and value.

Preparing the business case. A business case should be developed for all significant change initiatives and capital projects, including major IT projects. Business unit managers may take the lead in developing business cases for projects that benefit their departments. However, many projects cross business units, and the talents of a senior business analyst facilitate the difficult decisions that must be made to satisfy the often competing demands of all areas impacted by the change. The business analyst brings key experts together to gain agreement on the initiative. Accurately predicting the costs and benefits of major initiatives is a critical skill that requires the combined disciplines of business analysis, project management, and IT expertise to estimate the costs of software development and technology acquisition, as well as business prowess to predict the business costs and value.

![]() Conducting the initial risk assessment. Once the business case is developed, the business analyst facilitates a risk management session using the same set of experts. The BA and the experts identify and analyze key risks, develop risk responses, estimate the cost of the risk responses, and determine an overall risk rating for the project. This information is essential for the project selection and prioritization effort. Obviously, the organization strives to invest in projects that have the lowest risk and the highest probability of success.

Conducting the initial risk assessment. Once the business case is developed, the business analyst facilitates a risk management session using the same set of experts. The BA and the experts identify and analyze key risks, develop risk responses, estimate the cost of the risk responses, and determine an overall risk rating for the project. This information is essential for the project selection and prioritization effort. Obviously, the organization strives to invest in projects that have the lowest risk and the highest probability of success.

![]() Presenting new business opportunities to the portfolio management team for a decision on whether to fund the initiative as new programs and supporting projects.

Presenting new business opportunities to the portfolio management team for a decision on whether to fund the initiative as new programs and supporting projects.

PLANNING AND REQUIREMENTS ELICITATION

During the early project phases, the business need is analyzed and documented in as much detail as is needed to move into design and construction. The initial activities are planning and requirements elicitation. It is imperative to involve all stakeholders—including customers, users, business managers, architects, and developers—in these early activities.

BUSINESS ANALYSIS PLANNING ACTIVITIES

Ideally, the business analyst leads the business analysis planning activities in collaboration with a small core team consisting of the project manager, business visionary, and lead technologists. This team is charged with understanding the business opportunity, defining the scope of the effort at a more detailed level, determining the project approach (plan-based vs. adaptive), planning the business analysis activities to be completed and artifacts to be created, establishing a communication approach, defining a change-management method for requirements, conducting a stakeholder analysis, and ensuring a strong start to requirements elicitation.3

CAREER ADVICE

Planning

All too often, business analysts jump into requirements-gathering activities without adequate preparation. The result: inadequate time, budget, and resources to do a thorough job.

A Word to the Wise

Work closely with the project manager and business representatives to plan the approach to business analysis activities, tasks, resources needed, and artifacts to be produced.

With the PM, negotiate the commitment of the required business and technical SMEs and ensure their management commits individuals with the talent and knowledge to help create an innovative approach to the solution.

ELICITATION PREPARATION ACTIVITIES

The prudent business analyst spends a considerable amount of time preparing for the task at hand. Elicitation groundwork activities include:

![]() Gleaning a perspective of the needs and environment of customers, users, and stakeholders

Gleaning a perspective of the needs and environment of customers, users, and stakeholders

![]() Reviewing (or creating if nonexistent) the business case, project charter, and statement of work (or similar scope definition document)

Reviewing (or creating if nonexistent) the business case, project charter, and statement of work (or similar scope definition document)

![]() Understanding the business vision, drivers, goals, objectives, and expected value to the customer and business benefits for the new/changed solution

Understanding the business vision, drivers, goals, objectives, and expected value to the customer and business benefits for the new/changed solution

![]() Assembling and educating a requirements team comprising key business and technical stakeholders

Assembling and educating a requirements team comprising key business and technical stakeholders

![]() Further understanding and documenting the scope of the project

Further understanding and documenting the scope of the project

![]() Deciding which elicitation activities will be performed, selecting the documents and models to be produced, and developing the requirements management plan

Deciding which elicitation activities will be performed, selecting the documents and models to be produced, and developing the requirements management plan

![]() Defining/refining the checklist of requirements activities, deliverables, and schedule

Defining/refining the checklist of requirements activities, deliverables, and schedule

![]() Planning for change throughout the project.

Planning for change throughout the project.

ELICITATION GOALS

Requirements are conditions or capabilities that a solution must fulfill to support the essential activities of the enterprise. Requirements are derived from business goals and objectives. A critical success factor in the value of the solution after deployment is the extent to which it supports business requirements and helps the organization achieve its business objectives, so we must get requirements right. Requirements elicitation goals include:

![]() Identifying the customers, users, and stakeholders to determine who should be involved in the requirements gathering process.

Identifying the customers, users, and stakeholders to determine who should be involved in the requirements gathering process.

![]() Understanding the business goals and objectives and thus identifying the essential user tasks that support the organizational goals. Successful solutions will support the business requirements and facilitate achievement of organizational goals.

Understanding the business goals and objectives and thus identifying the essential user tasks that support the organizational goals. Successful solutions will support the business requirements and facilitate achievement of organizational goals.

![]() Identifying and beginning to document requirements for a target product, service, or system that will meet the needs of the users, customers, and stakeholders.

Identifying and beginning to document requirements for a target product, service, or system that will meet the needs of the users, customers, and stakeholders.

Many believe that requirements elicitation is the most critical and the most difficult aspect of a project.4 But most business analysts rate themselves as very proficient in elicitation, which indicates that they may be underestimating the importance of elicitation activities. To be successful in requirements elicitation, the business analyst must establish a collaborative partnership between customers, users, and the project team. The business analyst should not just be a note taker when working with these groups; she is called upon to encourage creativity, innovation, and exploration. Business analysts can improve their skills in conducting elicitation discussions by seeking out training in creativity and innovation, group facilitation and decision-making, conflict resolution, negotiation, and elicitation techniques and can build on the training through experience and working with a coach or mentor.

ELICITATION ACTIVITIES

Requirements are always unclear at the beginning of a project. It is through the process of progressive elaboration that requirements evolve into maturity—hence, the iterative nature of requirements gathering, documenting, and validating. This requirements discovery process involves conducting a variety of requirements-gathering sessions.

CAREER ADVICE

Brainstorming

Of all the elicitation tools in the BA toolbox, brainstorming is perhaps the most used and the most useful. It is during brainstorming sessions that the team identifies all of the ideas that it will consider. This is the most creative part of elicitation.

A Word to the Wise

Become expert at facilitating brainstorming sessions. All too often, business analysts do not challenge SMEs to reach for unfamiliar or uncommon approaches and truly innovative solutions. Some brainstorming sessions even reduce the team’s creative output.

ELICITATION TECHNIQUES

There is a vast array of requirements elicitation techniques. Select the techniques that are well suited to your stakeholder group to ensure success. Note that it may be necessary to educate your stakeholders on the techniques you plan to use prior to the actual events. Requirements-gathering techniques include:

![]() Requirements elicitation workshops. Requirements workshops link business users with solution developers and are an efficient way to gather information about business needs from a diverse group of stakeholders. The advantage of bringing stakeholders together to define requirements is that when conflicting and inconsistent requirements surface, they can be immediately resolved. Requirements are gathered quickly and collaboratively in a workshop session. A byproduct of these requirements workshops is that relationships begin to be built and ideally, a high-performing team begins to emerge.

Requirements elicitation workshops. Requirements workshops link business users with solution developers and are an efficient way to gather information about business needs from a diverse group of stakeholders. The advantage of bringing stakeholders together to define requirements is that when conflicting and inconsistent requirements surface, they can be immediately resolved. Requirements are gathered quickly and collaboratively in a workshop session. A byproduct of these requirements workshops is that relationships begin to be built and ideally, a high-performing team begins to emerge.

The business analyst plays a critical role in facilitating the workshop to ensure a successful outcome, which is a difficult endeavor. Requirements workshops require a considerable amount of planning and preparation to be successful. When a business analyst is new to an organization, it is helpful to bring in an outside facilitator so that the business analyst can observe the facilitation approach and focus on the discussion. Business analysts often use the brainstorming technique, which is designed to solicit as many innovative ideas as possible, to foster creative thinking.

![]() Interviews. BAs conduct interviews with individuals and small groups to find out what business functions must be supported by the new solution.

Interviews. BAs conduct interviews with individuals and small groups to find out what business functions must be supported by the new solution.

![]() Surveys. Surveys can be used to collect a large amount of information from an array of stakeholders efficiently and quickly. Surveys can be used to collect initial information or to test the information you have already gathered.

Surveys. Surveys can be used to collect a large amount of information from an array of stakeholders efficiently and quickly. Surveys can be used to collect initial information or to test the information you have already gathered.

Valid surveys are difficult to design and administer. To mitigate the risk of gathering inaccurate information from the survey, consult with a subject matter expert to help with the survey design and information compilation.

![]() Review of existing system and business documents. Conduct a review of all existing documentation about the business system, including policies, procedures, regulations, and process descriptions. Looking at market data about the business process under review can also be helpful.

Review of existing system and business documents. Conduct a review of all existing documentation about the business system, including policies, procedures, regulations, and process descriptions. Looking at market data about the business process under review can also be helpful.

![]() Observation. It is helpful to observe users conducting their day-to-day operational functions. This may help validate information gathered through workshops and interviews, resolve problems with requirements, and uncover missing requirements.

Observation. It is helpful to observe users conducting their day-to-day operational functions. This may help validate information gathered through workshops and interviews, resolve problems with requirements, and uncover missing requirements.

![]() Note-taking and feedback loops. Hold feedback sessions with customers, users, and stakeholders to continually validate the accuracy and completeness of the requirements.

Note-taking and feedback loops. Hold feedback sessions with customers, users, and stakeholders to continually validate the accuracy and completeness of the requirements.

ELICITATION DELIVERABLES

The key output of requirements elicitation is a very early iteration of documented business requirements that have been reviewed and approved by key business and technical stakeholders. Other artifacts of the process may include notes, documentation of issues or risks, diagrams, or other information captured during the elicitation sessions.

REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

Requirements are first stated in simple terms during the elicitation activities and are then analyzed, decomposed, and refined for clarity and accuracy. Requirements analysis is the process of structuring requirements information into various categories, evaluating requirements for selected qualities, representing requirements in different forms, deriving detailed requirements from high-level requirements, and negotiating priorities. While the focus of requirements elicitation is on understanding customer, user, and business requirements for the new solution, the focus of analysis shifts to understanding the solution itself and exploring the details of the problem domain. According to Scott Ambler, renowned software development guru, analysis represents the middle ground between requirements and design, the process by which your mindset shifts from what needs to be built to how it will be built.5 And Karl Wiegers defines analysis as:

The process of classifying requirements information into various categories, evaluating requirements for desirable qualities, representing requirements in different forms, deriving detailed requirements from high-level requirements, negotiating priorities, and so on.6

REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS ACTIVITIES

Requirements analysis involves organizing and prioritizing requirements, specifying and modeling requirements, capturing assumptions and constraints, and verifying and validating requirements.7 Requirements analysis includes the activities to determine required function and performance characteristics, the context of implementation, stakeholder constraints and measures of effectiveness, and validation criteria. Through the analysis process, requirements are decomposed and captured in a combination of textual and graphical formats. During requirements analysis, the business analyst should continually ask: “As this approach innovative enough, or simply business as usual?”

REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS TECHNIQUES

Analysis techniques are many. Indeed, it is often difficult for the business analyst to decide which techniques to use. A rule of thumb: use the techniques that encourage collaboration and innovation. Also, use the techniques that make the requirements visible. Finally, keep the process as simple as possible. Often-used techniques include the following:

![]() Context diagramming, to ensure that the scope of the change initiative and the boundaries of the project are fully understood by all stakeholders.

Context diagramming, to ensure that the scope of the change initiative and the boundaries of the project are fully understood by all stakeholders.

![]() Studying requirements feasibility to determine if the requirement is viable technically, operationally, and economically.

Studying requirements feasibility to determine if the requirement is viable technically, operationally, and economically.

![]() Trading off requirements to determine the most feasible requirement alternatives.

Trading off requirements to determine the most feasible requirement alternatives.

![]() Assessing requirement risks and constraints and modifying requirements to mitigate identified risks.

Assessing requirement risks and constraints and modifying requirements to mitigate identified risks.

![]() Modeling requirements to provide a visual depiction of relationships and dependencies: data models, process models, organization models, interface, and context models.

Modeling requirements to provide a visual depiction of relationships and dependencies: data models, process models, organization models, interface, and context models.

![]() Prototyping interfaces and solution subcomponents to provide a visual depiction of the proposed solution.

Prototyping interfaces and solution subcomponents to provide a visual depiction of the proposed solution.

![]() Analyzing business rules to determine what decisions have been made regarding business operations.

Analyzing business rules to determine what decisions have been made regarding business operations.

![]() Decomposing requirements to capture business needs in enough detail for the solution development team’s use.

Decomposing requirements to capture business needs in enough detail for the solution development team’s use.

![]() Clarifying and restating requirements in multiple ways to ensure they describe the real needs of the customers.

Clarifying and restating requirements in multiple ways to ensure they describe the real needs of the customers.

![]() Deriving additional requirements as more is learned about the business need through the analysis activities.

Deriving additional requirements as more is learned about the business need through the analysis activities.

![]() Prioritizing requirements to reflect the fact that not all requirements are of equal value to the business. Prioritization is necessary to ensure the most valuable features and functions are delivered to the business first.

Prioritizing requirements to reflect the fact that not all requirements are of equal value to the business. Prioritization is necessary to ensure the most valuable features and functions are delivered to the business first.

![]() Defining terms in a glossary or data dictionary in natural (nontechnical) language to ensure that stakeholders have a common understanding of them.

Defining terms in a glossary or data dictionary in natural (nontechnical) language to ensure that stakeholders have a common understanding of them.

![]() Creating test cases at a high level to ensure each requirement is testable.

Creating test cases at a high level to ensure each requirement is testable.

![]() Allocating requirements to subsystems to ensure they are satisfied by components of the system.

Allocating requirements to subsystems to ensure they are satisfied by components of the system.

REQUIREMENTS SPECIFICATION ACTIVITIES

Requirement specifications are elaborated from and linked to the structured requirements using a combination of textual statements, models, graphs, and matrices, resulting in a repository of requirements with a complete attribute set identifying specific characteristics of each requirement such as: owner, priority, status, author, and the like. Requirements must be sufficiently detailed, as they will be included in a solution specification document to be used by the development team. Through the process of progressive elaboration, the requirements team often finds requirements that are not defined in sufficient detail. These requirements must be made more specific to prevent uncontrolled changes to requirements.

Specification activities include identifying all the precise attributes of each requirement. This process ensures an understanding of the relative importance of each of the quality attributes.

REQUIREMENTS SPECIFICATION TECHNIQUES

Attributes are used for a variety of purposes, including structuring, grouping, explaining, selecting, and validating requirements. Attributes allow the requirements team to associate information with individual or related groups of requirements and often facilitate the requirements analysis process by filtering and sorting. In addition, attributes enable the association of descriptive information with each requirement. Attributes may be user defined or system defined.

CAREER ADVICE

Visualization

All too often, the project manager simply expects the BA to create a requirements document and perhaps use cases or user stories and then quietly go away. Unless requirements are visual, they are subject to interpretation and invalid assumptions.

Text is important when describing very technical information.

Models, graphs, and rich pictures are a necessity for demonstrating relationships, sequence, and dependencies and to promote a common understanding.

A Word to the Wise

Requirements alone are not complex; it is the relationships among requirements that create complexity.

Select a few models that you will always use to define requirements.

Become expert at facilitating modeling sessions.

Limit dependencies among requirements to reduce complexity.

Form a requirements integration team to manage requirement dependencies.

Use a requirements management tool to link and integrate requirements artifacts to maintain integrating throughout the project.

Typical attributes attached to requirements may include:

![]() A unique identifier that does not change. The identifier is not to be reused if the requirement is moved, changed, or deleted.

A unique identifier that does not change. The identifier is not to be reused if the requirement is moved, changed, or deleted.

![]() Acceptance criteria. These describe the nature of the test that would demonstrate to customers, end users, and stakeholders that the requirement has been met. Acceptance criteria are usually captured by asking end users, “What kind of assessment would satisfy you that this requirement has been met?”

Acceptance criteria. These describe the nature of the test that would demonstrate to customers, end users, and stakeholders that the requirement has been met. Acceptance criteria are usually captured by asking end users, “What kind of assessment would satisfy you that this requirement has been met?”

![]() Author of the requirement—the person who wrote it.

Author of the requirement—the person who wrote it.

![]() Complexity indicator, which communicates how difficult the requirement will be to implement.

Complexity indicator, which communicates how difficult the requirement will be to implement.

![]() Ownership—the individual or group that needs the requirement to be met.

Ownership—the individual or group that needs the requirement to be met.

![]() Performance, which addresses how the requirement must be met.

Performance, which addresses how the requirement must be met.

![]() Priority of the requirement—a rating of its relative importance at a given point in time.

Priority of the requirement—a rating of its relative importance at a given point in time.

![]() Source of the requirement, which identifies who requested it. Every requirement should originate from a source that has the authority to specify requirements.

Source of the requirement, which identifies who requested it. Every requirement should originate from a source that has the authority to specify requirements.

![]() Stability, an indicator of how mature the requirement is. This is used to determine whether the requirement is firm enough to begin work on it.

Stability, an indicator of how mature the requirement is. This is used to determine whether the requirement is firm enough to begin work on it.

![]() Status of the requirement, which denotes whether it is proposed, accepted, verified with the users, or implemented.

Status of the requirement, which denotes whether it is proposed, accepted, verified with the users, or implemented.

![]() Urgency, which refers to how soon the requirement is needed.

Urgency, which refers to how soon the requirement is needed.

REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION DELIVERABLES

The modeled and documented, validated, structured requirements are an output of the requirements analysis and specification process. The requirements must clearly demonstrate the business value to be delivered and must be traced back to specific business objectives outlined in the business case. It is helpful if the requirements are structured to mirror the solution design; this facilitates traceability from requirement to design and construction of the solution.

REQUIREMENTS DOCUMENTATION

Requirements must be documented in clear, concise, and natural language, since requirements documentation is used by virtually everyone associated with the project. Certain types of requirements, such as regulatory mandates, safety standards, environmental tolerances, and security requirements, may need to be expressed formally, using scientific or technical language. This is acceptable, as long as the requirements are mapped back to the business objectives (which should be easier to understand). However, in most cases the language used to document business requirements should be as simple and straightforward as possible. Characteristics of good requirements include:

![]() Feasibility. The requirements must be technically, economically, and operationally possible.

Feasibility. The requirements must be technically, economically, and operationally possible.

![]() Necessity. The requirements must represent the real needs of the organization.

Necessity. The requirements must represent the real needs of the organization.

![]() Prioritization. The requirements must be prioritized according to the value of the function or feature to the organization.

Prioritization. The requirements must be prioritized according to the value of the function or feature to the organization.

![]() Unambiguousness. The requirements must be clear so that they will be interpreted consistently across stakeholder groups.

Unambiguousness. The requirements must be clear so that they will be interpreted consistently across stakeholder groups.

![]() Completeness. The requirements must represent all of the functions and features that are needed to meet the business objectives.

Completeness. The requirements must represent all of the functions and features that are needed to meet the business objectives.

![]() Verifiability. The requirements must be testable.

Verifiability. The requirements must be testable.

![]() Consistency. The requirements must be in harmony with one another and must not contradict each other.

Consistency. The requirements must be in harmony with one another and must not contradict each other.

![]() Correctness. The requirements must accurately represent business functions and adhere to business rules.

Correctness. The requirements must accurately represent business functions and adhere to business rules.

![]() Modifiability. The requirements must be flexible so that they can be adapted to changing business needs.

Modifiability. The requirements must be flexible so that they can be adapted to changing business needs.

![]() Traceability. The requirements must be structured so that they can be traced to hardware, software, test cases, training manuals, and documentation artifacts throughout the product development life cycle.

Traceability. The requirements must be structured so that they can be traced to hardware, software, test cases, training manuals, and documentation artifacts throughout the product development life cycle.

![]() Usability after development. The requirements must be sufficiently detailed so as to support maintenance and enhancement of the product after deployment.

Usability after development. The requirements must be sufficiently detailed so as to support maintenance and enhancement of the product after deployment.

TEXTUAL VS. GRAPHICAL REQUIREMENTS DOCUMENTATION

A diagram can express structure and relationships more clearly than text, whereas for precise definition of concepts, clearly articulated language is preferred to diagrams. Therefore, both textual and graphical representations are essential for a complete set of requirements. Transforming requirements represented graphically into textual form can make them more understandable to nontechnical members of the team.

CATEGORIZING REQUIREMENTS

Requirements are categorized into types depending on their source and applicability. Understanding requirement types helps in analyzing, structuring, and prioritizing requirements and enables the technical team to conduct trade-off analysis, estimate the system cost and schedule, and better assess the level of requirement changes to be expected. Finally, reviewing the list of requirement types can help the business analyst identifying areas that may require further investigation.

Typically, requirements are broadly characterized as functional or nonfunctional (aka supplemental). Functional requirements are capabilities the system will be able to perform in terms of behaviors or operations. They are specific system actions or responses. A functional requirement is best expressed as a verb or verb phrase. Functional requirements are written so as not to unnecessarily constrain the solution, thus providing a firm foundation for the system architects.

Nonfunctional requirements stipulate a physical or performance characteristic and serve as constraints on system capabilities. Constraints pose restrictions on the acceptable solution options. Technical constraints may include the requirement to use a predetermined language or database or specific hardware. Constraints may also specify restrictions such as resource utilization, message size and timing, software size, or the maximum number of and size of files, records, and data elements. Technical constraints also include any enterprise architecture standards that must be followed. Business constraints include budget limitations, restrictions on the people who can do the work, and the skill sets available. Business rules define the constraints on business processes that must be followed.

REQUIREMENTS VALIDATION

Documentation activities involve translating the collective requirements into written requirements specifications and models in terms that are understood by all stakeholders. The process of validating requirements typically requires substantial time and effort, as each stakeholder may have different expertise, perspectives, and expectations.

Requirements validation is the process of evaluating requirements documents, models, and attributes to determine whether they satisfy the business needs and are complete to the point that the technical team can commence work on solution design and development. The set of requirements is compared to the original initiating documents (e.g., the business case, project charter, or statement of work) to ensure completeness. If a requirement cannot be traced to a business adjective, it may not be valid.

Beyond establishing completeness, validation activities include evaluating requirements from a technical standpoint to ensure that design risks associated with the requirements are minimized before further investment is made in system development.

CAREER ADVICE

Requirements Validation

Requirements validation occurs throughout the project, not just in the early elicitation and analysis stages.

A Word to the Wise

Requirements emerge; many iterative sessions are needed to fully understand and capture requirements.

Seek ways to continually validate requirements, assess the solution as it comes into view, and validate that the solution will satisfy the business need.

Insert many solution assessment and validation sessions into your business analysis plan.

REQUIREMENTS VALIDATION ACTIVITIES

The objective of requirements validation is to ensure that all business and technical stakeholders have reviewed the requirements, identified errors and omissions, and made corrections so that the solution team can proceed with solution design, construction, and testing. Requirements are also used by the project manager to prepare time and cost estimates for the project.

REQUIREMENTS VALIDATION TECHNIQUES

Validation techniques include defining acceptance criteria and conducting document reviews, product demonstrations, prototyping, and finally user acceptance testing to ensure the criteria have been satisfied.

![]() Prototyping. The best representation of the solution is the solution itself. Therefore, the most useful technique for validating that analysis is complete is prototyping, which provides a visual model of the solution or a component of the solution.

Prototyping. The best representation of the solution is the solution itself. Therefore, the most useful technique for validating that analysis is complete is prototyping, which provides a visual model of the solution or a component of the solution.

![]() Test-driven requirements. If requirements are particularly difficult to define, it is sometimes necessary to start by designing the test that will verify that the requirement has been met, and then back into the actual requirement.

Test-driven requirements. If requirements are particularly difficult to define, it is sometimes necessary to start by designing the test that will verify that the requirement has been met, and then back into the actual requirement.

![]() Business scenarios (aka usage-based scenarios) are often used to ensure an understanding of business requirements.

Business scenarios (aka usage-based scenarios) are often used to ensure an understanding of business requirements.

![]() Acceptance criteria. Developing acceptance criteria, performance metrics, and business benefit measures is another good way to ensure requirements are complete and acceptable to the business.

Acceptance criteria. Developing acceptance criteria, performance metrics, and business benefit measures is another good way to ensure requirements are complete and acceptable to the business.

![]() Structured walkthroughs of the solution with key customers and users is an effective way to validate that the requirements are accurate, complete, and unambiguous.

Structured walkthroughs of the solution with key customers and users is an effective way to validate that the requirements are accurate, complete, and unambiguous.

REQUIREMENTS MANAGEMENT

A major requirement review occurs once firm, basic requirements are complete enough to transition to the more detailed work of defining system specifications, and designing and constructing the solution design. This involves presenting requirements for review and approval at a formal session. At this point, the project manager updates the project schedule, cost, and scope estimates and the business analyst updates the business case to provide the salient information needed to determine whether continued investment in the project is warranted. Upon securing approval to proceed, the business analyst transitions into requirements management activities.

Once the requirements are defined, approved, and baselined, changes to these firm, basic, approved requirements must be managed throughout the solution development life cycle. Requirements management involves tracking and coordinating requirements allocation, status, and change activities throughout the rest of the business solutions life cycle. Spreadsheets and traceability tools that help validate that all requirements have been satisfied by solution components are the most common requirements management tools. The business analyst and project manager work collaboratively to define and manage the project and product scope. Requirements management activities include:

![]() Allocating requirements (also referred to as partitioning) to different subsystems or subcomponents of the system. Top-level requirements are allocated to components defined in the system architecture, such as hardware, software, manual procedures, and training.

Allocating requirements (also referred to as partitioning) to different subsystems or subcomponents of the system. Top-level requirements are allocated to components defined in the system architecture, such as hardware, software, manual procedures, and training.

![]() Tracing requirements throughout system design and development to track where in the system each requirement is satisfied. As requirements are converted to design documentation, the sets of requirements documentation, models, specifications, and designs must be rigorously linked to ensure that the relevant business needs are satisfied.

Tracing requirements throughout system design and development to track where in the system each requirement is satisfied. As requirements are converted to design documentation, the sets of requirements documentation, models, specifications, and designs must be rigorously linked to ensure that the relevant business needs are satisfied.

![]() Managing changes and enhancements to the system. Managing requirements involves being able to add, delete, and modify requirements during all phases of the system development life cycle.

Managing changes and enhancements to the system. Managing requirements involves being able to add, delete, and modify requirements during all phases of the system development life cycle.

![]() Validating and verifying requirements. The business analyst continues to facilitate the validation and verification of requirements throughout the development life cycle. The purpose of verification and validation is to ensure that the system satisfies the requirements as well as the specifications and conditions imposed on it by those requirements. Validating requirements provides evidence that the solution satisfies the business requirements and is done through user involvement in testing, demonstration, and inspection techniques. The final validation step is the user acceptance testing, led and facilitated by the business analyst. Verifying requirements provides evidence that the solution satisfies the technical specifications and is done through testing, inspection, demonstration, analysis, or some combination of these.

Validating and verifying requirements. The business analyst continues to facilitate the validation and verification of requirements throughout the development life cycle. The purpose of verification and validation is to ensure that the system satisfies the requirements as well as the specifications and conditions imposed on it by those requirements. Validating requirements provides evidence that the solution satisfies the business requirements and is done through user involvement in testing, demonstration, and inspection techniques. The final validation step is the user acceptance testing, led and facilitated by the business analyst. Verifying requirements provides evidence that the solution satisfies the technical specifications and is done through testing, inspection, demonstration, analysis, or some combination of these.

MANAGING CHANGES TO REQUIREMENTS

Managing changes to requirements is a difficult endeavor. How the business analyst manages change depends on the complexity of the project, the time-to-market urgency for the solution, the volatility of the business climate, and the level of understanding of the requirements. We will examine the nature of change control for projects of varying complexity.* In Chapter 3, we fully examine changes to the role of the business analyst for varying levels of project complexity.

FIGURE 2-3. The Waterfall Model

MANAGING REQUIREMENTS ON PROJECTS OF LOW TO MODERATE COMPLEXITY

For short-duration projects with stable requirements and few dependencies, the waterfall model depicted in Figure 2-3 is highly effective for managing requirements. This linear ordering of activities presumes requirements are complete before design and construction begin. It assumes that events affecting the project are predictable, tools and activities are well-understood, and once a phase is complete, it will not be revisited.

CAREER ADVICE

Welcome Change!

Requirements will change—there is no doubt about it. Our requirements practices are not effective enough to gather all requirements early and then fiercely control changes. And the world is changing all around us, so we must embrace change.

A Word to the Wise

Two very effective approaches:

Welcome changes that add value to the customer and wealth to the organization.

Reduce the cost of change through iterative development and by limiting dependencies among requirements and solution components.

The strengths of this approach are that it lays out the steps for development and stresses the importance of requirements. The limitations are that projects rarely follow the sequential flow, and it is difficult to state all requirements up front. Therefore, once design and construction begin, change management systems are needed to:

![]() Identify the business need and value of a proposed change

Identify the business need and value of a proposed change

![]() Analyze the feasibility of change within cost and time constraints

Analyze the feasibility of change within cost and time constraints

![]() Recommend acceptance, deferral, or rejection of the change based on the business need

Recommend acceptance, deferral, or rejection of the change based on the business need

![]() Seek approval

Seek approval

![]() Implement approved changes.

Implement approved changes.

If no organizational change management process exists, or if the project will deviate from the standard process, it is the job of the project leadership team to develop a change management plan that includes the elements listed above. If the project deliverable is urgently needed, the team should strive to minimize scope and prevent change. Tools typically used to successfully control changes are low-tech tables and spreadsheets.

MANAGING REQUIREMENTS ON HIGHLY COMPLEX PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS

Since complex projects are by their very nature less predictable, it is important for the project team to build options into the approach. This often involves rapid prototyping—a fast build of a solution component to prove an idea is feasible—which is typically used for high-risk components, requirements understanding, or proof of concept. The spiral model, an iterative waterfall approach, is often used. Another option is the evolutionary development model, which implements the solution incrementally based on experience and lessons learned from the results of prior releases. Functions are prioritized based on business value, and once high-risk areas are resolved, the highest value components are delivered first.

This “keep our options open” approach requires a change management system that welcomes changes that add value and strives to reduce the cost of change. It is only necessary to control changes on the current increment, since little time has been invested in defining the scope of increments to be developed in the future. Iterative development requires a flexible approach to change management. The project team strives to welcome and manage change, not to prevent it. Tools used to track changes for complex projects are sophisticated configuration management systems.

MANAGING REQUIREMENTS ON MEGAPROJECTS

For megaprojects, a “conspiracy of optimism” takes hold, which drives us to estimate costs significantly lower than they will really be. We are optimists; if we knew the real costs of a megaproject at the outset, they would likely kill the project. So we forge ahead, due to political and commercial pressures. For example, the Boston Big Dig is modern America’s most ambitious urban-infrastructure project, spanning the terms of six presidents and seven governors. The cost of the project, which features many never-before-done engineering and construction marvels, rose from $2.6 billion to $14.8 billion over its duration.8

Implementing an effective change management system for megaprojects is difficult. Teams of people, a political management plan, a highly complicated change control process, and sophisticated tools are needed to traverse the litany of inevitable changes.

MANAGING TRANSITIONAL REQUIREMENTS

Planning for the organizational change that is brought about by the delivery of a major new product or business solution is often partially or even completely overlooked by project teams that are focused solely on system development and implementation of the IT application. While the technical members of the project team plan and support the implementation of the new product or system into the IT production environment, the business analyst’s role in solution delivery involves working with the management of the business unit to bring about the benefits expected of the new solution. To that end, the business analyst performs several assessments, which will help her understand organizational change management requirements.

![]() Readiness assessment. Assessing the organizational readiness for change and planning and supporting a cultural change program.

Readiness assessment. Assessing the organizational readiness for change and planning and supporting a cultural change program.

![]() Skill assessment. Assessing the current state of the knowledge and skills resident within the business, determining the knowledge and skills needed to optimize the new business solution, and planning for and supporting training, retooling, and staff acquisition to fill in skill gaps.

Skill assessment. Assessing the current state of the knowledge and skills resident within the business, determining the knowledge and skills needed to optimize the new business solution, and planning for and supporting training, retooling, and staff acquisition to fill in skill gaps.

![]() Organizational assessment. Assessing the current state of the organizational structure within the business domain, determining the organizational structure needed to optimize the new business solution, and planning for and supporting organizational restructuring.

Organizational assessment. Assessing the current state of the organizational structure within the business domain, determining the organizational structure needed to optimize the new business solution, and planning for and supporting organizational restructuring.

![]() Communication assessment. Developing and implementing a robust communication campaign to support the organizational change initiative.

Communication assessment. Developing and implementing a robust communication campaign to support the organizational change initiative.

![]() Management support assessment. Determining, enlisting, and supporting management’s role in the championing the change.

Management support assessment. Determining, enlisting, and supporting management’s role in the championing the change.

MANAGING CULTURAL CHANGES

Many cultural and physical barriers to adoption of a major change initiative exist. The business leadership may have too many conflicting and demanding priorities. The physical facilities needed to support the new product or business solution may not be well understood. The users—the actual operators of the new process or system—may not have the knowledge and skills needed to optimally use the new technology. The go-to-market commercial practices may need to be overhauled. It may be difficult to secure active involvement from the organization’s senior leadership because they may not believe that it is their role to model and teach the new practices.

Overcoming barriers to cultural change may involve major shifts to the organization’s legacy vision and skills. There are many strategies the business analyst can employ for making change work, including the following:

![]() Working with the leadership team to create a climate where change can succeed

Working with the leadership team to create a climate where change can succeed

![]() Enlisting formal and informal leaders within the organization to drive the change

Enlisting formal and informal leaders within the organization to drive the change

![]() Ensuring there is clear ownership and accountability within the business unit(s) for the quality of the new business process and IT systems

Ensuring there is clear ownership and accountability within the business unit(s) for the quality of the new business process and IT systems

![]() Focusing on and communicating improvements early in the deployment

Focusing on and communicating improvements early in the deployment

![]() Providing role modeling, mentoring, and coaching to reinforce new business practices

Providing role modeling, mentoring, and coaching to reinforce new business practices

![]() Implementing reward and recognition systems that are aligned with the new business practices

Implementing reward and recognition systems that are aligned with the new business practices

![]() Reacting to critical incidents with the new business solution quickly

Reacting to critical incidents with the new business solution quickly

![]() Recognizing and addressing stress and resistance associated with culture change

Recognizing and addressing stress and resistance associated with culture change

![]() Employing strategies to sustain culture change, including:

Employing strategies to sustain culture change, including:

![]() Coaching and mentoring programs

Coaching and mentoring programs

![]() Permanently linking rewards to the use of new business practices

Permanently linking rewards to the use of new business practices

![]() Placing equal emphasis on all aspects of the business system, including customer satisfaction, profit, employee satisfaction, continuous learning, process efficiency, and driving value through the organization to the customer.9

Placing equal emphasis on all aspects of the business system, including customer satisfaction, profit, employee satisfaction, continuous learning, process efficiency, and driving value through the organization to the customer.9

MAINTAINING AND ENHANCING THE SOLUTION

The business analyst’s contribution to the success of the project does not end when the business solution is delivered and operational. The business analyst is responsible for tracking and reporting the actual business costs and benefits that have been realized as a result of the new solution.

CAREER ADVICE

Benefits Management

To close the loop in the portfolio management process, the actual costs and benefits need to be measured and compared to those forecasted in the business case.

A Word to the Wise

It is the responsibility of the business analyst to:

Measure the actual costs and benefits that were/are being realized via the new or changed solution.

Report the results to the executive sponsor and the portfolio management team.

If the forecasted benefits were not realized, the BA conducts root cause analysis to determine what went wrong (e.g., the cost and time estimates were too optimistic, the project was not executed optimally, or the solution is not operating efficiently and is more costly to maintain than anticipated). The results of the root cause analysis are included in the benefits report with recommendations for improvement to avoid similar situations in the future.

The business analyst also maintains key responsibilities during the operations and maintenance (O&M) phase of the business solution life cycle. O&M is the phase in which the system is operated and maintained for the benefit of the business. The business analyst provides maintenance services to prevent and correct defects in the business solution. These defects could be problems with the IT system (e.g., inaccurate data, application defects, or technical infrastructure inadequacies) or issues within the business process (e.g., procedure inefficiencies, information gaps, or skill gaps).

Documentation produced and reviewed by the business analyst includes process efficiency measures, customer satisfaction indicators, system validation procedures, system validation reports, maintenance reports, annual operational reports, and the deactivation plan and procedures. The business analyst also plays a major role in managing enhancements to the system and in determining when the system should be replaced and therefore deactivated. (Enhancements are defined as changes to increase the value provided by the system to the business.) Clearly, if requested enhancements cost more to implement than the value provided to the business, they are not cost-effective. It is the business analyst who continues to examine the value proposed functions and features will bring about, comparing it with the cost to develop and operate the new system components.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: WHAT DOES THIS MEAN TO THE BUSINESS ANALYST?

The business analyst is integral throughout the project. Many organizations are of the erroneous opinion that the business analyst simply needs to elicit and document requirements. After this, she is no longer needed, so she can then move on to another project. The truth is that developing business requirements is an iterative process. Requirements emerge as more is learned about the business, the solution, and the evolving business needs. Therefore, it is imperative that the business analyst remain an essential member of the complex project leadership team throughout the project. Indeed, the business analyst plays a critical role even after the project is closed, adding value to the solution and measuring the actual business benefits achieved.

NOTES

1. Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

2. International Institute of Business Analysis, A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge (BABOK® Guide), Version 2.0 (Toronto: International Institute of Business Analysis, 2009): 81–98.

3. Ibid., 17–52.

4. Karl Wiegers, Software Requirements: Practical Techniques for Gathering and Managing Requirements throughout the Product Development Cycle, 2nd ed. (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2003): 45.

5. Scott Ambler, “Agile Analysis,” 2010. Online at http://www.agilemodeling.com/essays/agileAnalysis.htm (accessed July 2010).

6. Wiegers, 483.

7. BABOK® Guide, 99–120.

8. Nicole Gelinas, “Lessons of Boston’s Big Dig,” City Journal (Autumn 2007). Online at http://www.city-journal.org/html/17_4_big_dig.html (accessed July 2010).

9. Rita Chao Hadden, Leading Culture Change in Your Software Organization: Delivering Results Early (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2003).

* This section on managing changes to requirements is adapted with permission from “Change: Manage It, Prevent It, or Welcome It?,” a PMI® Community Post by Kathleen B. Hass (June 25, 2010). Project Management Institute, PMI® Community Post, Project Management Institute, Inc., 2010. Copyright and all rights reserved. Material from this publication has been reproduced with the permission of PMI.