Chapter 3

Planning

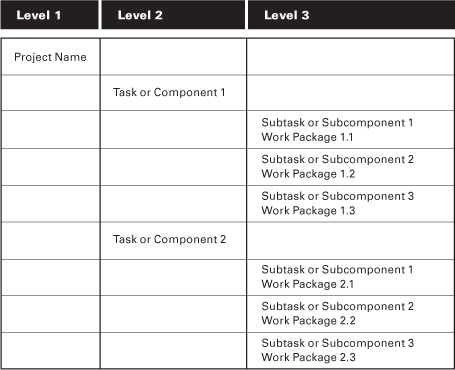

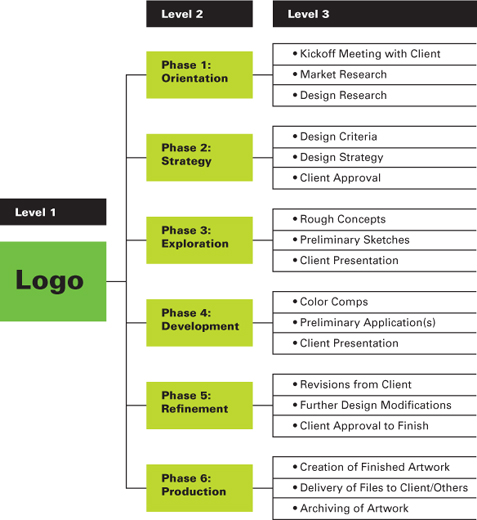

WBS for a Logo Design

This is a WBS diagram for a simple logo project. The WBS could also contain a level 4 that identifies the tasks required to accomplish the major milestones listed in level 3. A WBS can break down the work to the finest detail, or it can provide more of an overview as this chart does. A further refinement would be to add due dates and even assign a person responsible for doing the work. Each person on the project may then wish to create his or her own work breakdown either as a diagram or as a simple to-do list.

Scheduling Design

After everyone understands the work to be done, the next aspect of planning to address is scheduling. Sometimes in design, the only two clear dates are the day the client gives approval to start the job and the day they want the work delivered. Some clients might also specify a few key dates in between, but typically the onus is on the designer to develop due dates and milestones for each phase of the project.

Creating a Flexible Framework

Design project managers must understand that scheduling is an ongoing, dynamic activity. It is rare for a design project to follow the initial schedule exactly. Dates slip and slide for several reasons, mostly related to the client (e.g., the client doesn’t provide a vital piece of information required to proceed, fails to sign off on some work, or makes additional changes). If a manager thinks of scheduling as a flexible framework, but is very clear on which deadlines must not be missed, he or she will run a saner project.

To facilitate scheduling, communication between the design team and the client must clearly spell out responsibilities and critical requirements. The client also must understand that any missed deadlines on their part will affect all subsequent due dates and deadlines. It’s pretty much a cardinal rule for a graphic design firm not to miss any deadlines; clients can miss deadlines, but designers cannot. If a deadline issue arises, it is best to alert the client as early as possible that there is a problem and the work will be late. It’s all about managing client expectations and satisfaction.

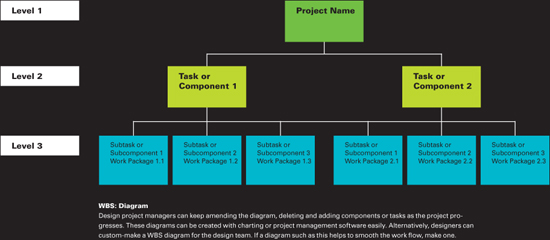

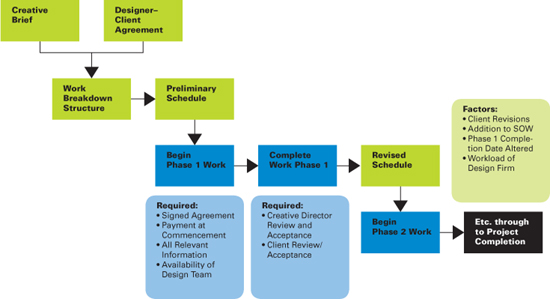

The diagram below provides an overview of the design scheduling process. It is helpful for a project manager to clearly understand what is required for each phase of work. A big mistake is to tell the design team to begin work without all the elements they need to do the work. This problem is compounded when promises to the client are made regarding due dates, based on that misinformation. A formal scheduling and planning process improves logistics, avoids wasted time, and helps the team stay on track.

Design Project Scheduling Process

Time Management

Strictly speaking, time management is an ongoing activity that all team members must engage in throughout a design project. However, it is an issue to address upfront in the planning of a design project as well. When scoping the work (see page 40) and then creating a thorough WBS (page 66), the project manager knows exactly what will be done and the hierarchical nature of the tasks (if relevant). He or she has also determined approximately how much time it will take to complete the tasks and has committed all of this information into a schedule. This is great in theory, but will it work in reality? This is where time management checks and balances are helpful in staging a job and staying on track with the projected work flow.

Designers Need Time Sheets

The best tool to aid in time management is time sheets, which record in fifteen-minute intervals what a designer is doing during his or her workday. Many designers resist this practice—mostly because it is tedious. Some also believe time sheets are irrelevant if a project has a fixed fee, instead of being billed hourly. That is a short-sighted notion. Time sheets are extremely valuable because they are an essential tool for ensuring profitability and estimating future work.

Time sheets allow design managers to track the team’s progress. By reviewing time sheets on an ongoing basis (daily or at least weekly is most useful), a manager can understand if the amount of time he or she planned for the work is going forward as envisioned. Knowing this earlier rather than later means the manager can

• Uncover performance flaws in the team and hopefully rectify the situation

• Question why the work isn’t being done as planned, often uncovering the need for a change order to the client

• Reduce the time allotted in later phases of work if possible, to make up for increased time consumption in earlier phases

• Request additional time from the client

Involve the Client

Because any schedule is bound to change, a project manager should notify the client that the schedule may need to undergo alterations. If the client knows this upfront, designers have a much better chance of managing the client’s expectations and heading off trouble and misunderstandings.

Planning and scheduling design is about forecasting. It’s about making educated guesses and watching how these guesses play out in reality. Time management analysis—at the onset and throughout the project—is critical. A great project manager will look at the facts, such as time sheets and the completed work, and extrapolate out toward the final goal. Close observation of how the team is spending their time will allow the project manager to make better scheduling decisions in the future. Plus, a manager may be able to adjust the schedule for the current project by renegotiating with the client.

Scheduling Software

Project management software usually contains a scheduling component. These are often robust, and sometimes too labor intensive for the needs of many design projects. One great aspect of using this software is that it typically is linked to email. This is useful for alerting the manager or team members with built-in warnings about how much time has been used to date. Some designers simply use a web-based shared calendar as their project scheduling device. Others like project status reports that are essentially daily to-do lists emailed to the team. Still others have quick daily face-to-face team meetings to review the previous day’s work and chart the course for that day’s activities. Use whatever level of complexity and detail your team prefers.

Software Shows What Takes Precedence

Nearly every design firm will benefit from someone looking at the firm’s overall work flow and capacity. A manager needs to look at any potentially conflicting due dates and client demands. One of the best ways to facilitate this is to use scheduling software.

The relationship between and among the different activities required to complete a project that must be done in a particular sequence is called a precedence relationship. Software is a good means for tracking and managing these relationships. A map of the tasks that must be completed before the next step is begun can easily be visualized in a Gantt chart (see page 69), which many scheduling software programs create.

Software Helps Contingency Planning

Design managers may wish to build in some extra time to complete a task or phase of work, by indicating on the schedule that the work will take longer than they know it will. This is called contingency planning. Building in time contingency, and then managing to that time frame, will help the team stay on schedule. For example, if an activity is slated to be done on Thursday, ask for the work at the end of the day Wednesday to ensure that the work is completed for Thursday. Allowing some slack in a schedule means a manager has a little bit of a buffer, and understands precisely how much a schedule can slip before it causes real delays and problems for the project.

One caveat: Giving false due dates and then sitting on the work or making arbitrary additional changes to it because you have the time will annoy the design team and undermine your credibility.

Details, Details, Details: Asset Management

Planning is a multitiered exercise. Trying to conceive of every possible contingency in a design project is an exercise in futility. It’s best to just review the major issues, forecast as much as possible, and adapt as the project moves from point A to point Z. So many things can go wrong in a design project, and most of them concern missed details—those hundreds of little things that must be factored in, remembered, and utilized to develop great design. Doing the job right means getting those details right.

From the beginning, you must set up a means of communication and sharing creative assets. An asset is any file, physical object, element, or artifact that is created or utilized for a design project. Asset management is not strictly a planning issue, but you must plan a work flow method among designers that supports good collaboration. If you’ve ever seen a design team’s work stopped or delayed because they printed out the wrong version of a file or they must revise finished art because they used the wrong version of the client’s logo, you’ve seen the problems inherent in not managing the details and assets of a job properly. These issues can cost significant time and money.

Good File Hygiene

Because nearly all of the designers’ work product—whether in progress or finished—is digital, creating a basic digital asset management system is fast and relatively easy. However, it takes some time and a lot of commitment to maintain the system on an ongoing basis. Here are the rules for using a bare-bones digital asset management system:

• Use unique job numbers for each project (see page 51).

• Set up a folder for each client.

• Within the client folder, place folders for each unique job number.

• Within each numbered job folder, create a subfolder called:

• RESEARCH (all background information)

• IMAGES (all illustrations, photography, and logos to be used in the work)

• STUDIES (all work in progress)

• PRESENTATIONS (all client presentations and PDFs)

• FINALS (all finished art)

• COPY (all copy and text to be used in the job)

• Name each document in all of these files consistently with a date and job number code; for example, 01_02_10_ABC101

If everyone on the design team understands the naming and filing conventions—whether it is the system suggested here or something else—and complies with it, the project’s assets will be easy to find and use. The result is a consistently and properly managed scheme for good file hygiene that will reduce time consumption, improve work flow, cut down on errors, help avoid duplication of effort especially because of lost items, boost collaborative sharing, and promote efficiency, all of which will improve responsiveness, speed up the work, and reduce costs.

A variety of software solutions—web-based and internal network—aid in digital asset management. They involve tagging the files with metadata (e.g., client information, file type, categories, graphic elements, classification, media, designer name, version codes, etc.) and can be expensive and time-consuming to administer. But in large organizations with many users, multiple projects, and, especially, various branches, it is worth the time and effort to implement one of these systems.

Benchmarking

Because graphic design is an iterative and collaborative process, logical points, benchmarks, or milestones occur during the course of work and present themselves at the end of phases (see the process chart on pages 10–11 for more information about phases of work).

In business, the word benchmark suggests certain standards being met. In design, it typically is used to mean a phase deadline for completion of a certain amount of work. If we merge the two meanings and look at benchmarking in planning as finishing the work to a particular standard of expectation, benchmarking becomes a holistic tool for monitoring the design process.

Graphic Design Benchmarks

Here are some common design project benchmarks:

• Kickoff meeting

• Creative brief

• Design criteria

• Design strategy

• First presentation of design

• Design refinements

• Approval of final design

• Release of finished artwork files

What Impacts Benchmarks?

When looking at how well the design team is meeting their goals and benchmarks, review the following items, as they impact the success of benchmarks:

• Creative Leadership

Having a clear vision, understanding and providing feedback based on a creative brief, and coaching and mentoring the design team to get the best creative out of them. Typically, this is the creative director’s job, but it also is heavily affected by the client.

• Rigorous Culture

Having an environment where deadlines are respected, work flow is orderly, and yet creative excellence is also revered. For both business and design, creative excellence is a result of a vigorous culture.

• Skilled Personnel

Not just having enough people, but the right people, working together on the project. Each person has definite roles and responsibilities. These people must possess creative muscle and know how to use it.

• Proper Motivation

Having a love for the challenge of solving problems and utilizing talent. There probably are lazy designers in the world, but most designers are intensely motivated to do great work, and they genuinely enjoy the design process. Designers who don’t feel this way probably are in the wrong profession.