Physical Investigations

Information in this chapter:

Introduction

In the world of digital forensics, getting lost in the data happens quickly and easily. This chapter focuses on physical investigations, detailing only those points useful in supporting currently available electronic evidence, or finding additional sources of electronic evidence.

The physical investigation and surveillance of a computer related crime perhaps best places the suspect behind a keyboard. The physical investigation should not be overlooked in any case where doubt exists to the actual suspect tied to activity with a computer. The forensic analysis to uncover the criminal activity is equally as important as finding the person responsible for the crime, as finding evidence of a crime does not complete an investigation by itself. The culprit needs to be identified and brought to justice with a complete and thorough investigation.

Understandably, not all digital forensic examiners will conduct physical investigations in addition to their forensic duties. For the forensic examiners having the luxury of solely working in a forensic lab, this chapter simply provides an overview of physical evidence collection techniques outside the lab and encourages forensic examiners to communicate with case investigators.

Equally important, investigators not tasked with forensic analysis should communicate their investigative findings to their forensic analysts. An ongoing theme in any investigation is that the small and unimportant details are unimportant, until they are not. The point at which a small detail becomes most important is when connections between collected data are made, and usually these previously unimportant details become most important. The key is to share information; every piece of the investigative puzzle is needed to complete it.

The investigative methods in this chapter are geared toward those techniques to physically place a person at a location, at a specific time, using a variety of measures. The importance of knowing where a suspect was located at any specific place and time cannot be understated. The objective of establishing a physical nexus between persons and places is what makes or breaks an alibi. Since a suspect’s presence at a specific location during a specific time is of utmost importance, all information related to time and place must be documented thoroughly. This includes information given by the suspect during interviews, witness statements, and physical surveillance conducted.

Not every method can be used in every investigation for a multitude of reasons. Some of these reasons include not having the legal authority or that the method may be ineffective in collecting the evidence sought. An example of having a lack of legal authority would be civil litigation investigation where a wiretap approval would not be possible. With suspects that are not mobile, wherein the suspect may never leave their residence, aerial or mobile surveillance would be ineffective.

As you read through the methods of physical surveillance, keep in your mind that the ultimate goal here is that you are building a timeline of the suspect’s activity. During the digital forensics analysis of electronic media, in which a timeline of user activity may be created, the timeline of the suspect’s locations (and activities?) will similarly be needed to paint a complete picture of the investigation.

With any investigation undertaken by an investigator or forensic examiner, one of the most important questions to ask is, “Is this legal?” When in doubt, ask for legal guidance. This not only includes the private sector investigator or forensic examiner, but also law enforcement. Of serious legal ramifications are violations of intercepting electronic communications. As jurisdictions differ in authority and case law fluxes over time, no two cases will be alike.

Hazards of Acting Upon Minimal Information

Acting upon information based solely derived from a computer system can have disastrous effects to the investigation and persons if additional steps are not taken to corroborate and confirm investigative findings. In some instances, acting upon minimal information can be unsafe for investigators responding to a scene, whereas in other cases, innocent persons can be affected and inaccurately labeled and arrested as offenders.

Obviously, many situations demand action with time being precious and gathering additional information may not be practical. However, when there is time to corroborate information and test assumptions, you should take the time. Otherwise, you may cause certain personal and professional disasters to both investigators and innocent persons with a poor investigation. No law enforcement professional wants an innocent person to be arrested or charged because such an incident damages both the innocent person and investigators, personal and professional reputations. Not to mention, few of us want a news crew on our lawn asking about mistakes that may have been made.

One example of an unintended consequence due to not taking extra necessary steps for corroboration started on July 3, 2007, with a tip from the Washington’s Missing and Exploited Children Task Force to the Washington State Patrol. This tip originated from the web-hosting company, Yahoo!, which had found images of child pornography on a hosted website. The tip was accurate as child pornography images did exist on the website and undoubtedly deserved law enforcement attention.

During the investigation, detectives from the Washington State Patrol obtained search warrants for subscriber information on the websites, which included IP addresses and billing information. Billing records showed that Nicole Chism had paid for the hosting through a credit card, with her correct residence address, phone number, and credit card number.

Several IP addresses used to log in to the website were traced back to physical addresses, however, the addresses were not the Chism’s residence. Even as the IP addresses used were traced back to locations across the state and out of state and none traced to the Chism residence, a search warrant was served at the Chism residence and the workplace of Todd Chism, a Lieutenant at the Spokane Fire Department.

After a forensic analysis of computers from both the Chism home and workplace, no evidence of child pornography was found. No charges were filed. Todd and Nicole Chism endured the stress of being targeted in a felony investigation along with the negative public attention that usually accompanies the arrests of pedophiles. Yet, both were apparently not only innocent of the charges, but oblivious to any suspected criminal activity.

The point to be made is that corroborating information through other means is imperative on many levels. If for no other reasons than to physically place a suspect at a crime scene, consider the extra steps to also prevent innocent citizens from being wrongfully targeted or placed under suspicion/investigation. Even in this case, certain facts were not making sense, such as IP addresses being traced across the state and none tracing back to the Chism residence.

Other facts such as previously reported stolen credit cards and nonsensical information obtained in the subscriber records should give investigators pause to gather more information. Some of the nonsensical information included incorrect personal information in the subscriber records obtained by the Washington State Patrol.

As any investigator that has been party to any situation such as this knows, the fact that a wrongfully charged criminal case based upon an inadequate or negligent investigation will end quickly is not much of a consoling factor. The imminent civil litigation that usually ensues afterward is much longer lasting. Such is the case of Chism v Washington (2011).

Physical Surveillance

Investigators must keep an open mind when conducting physical surveillance of a suspect. The intention may be to identify locations the suspect frequents and commits crimes using various computer systems and network access, but it may also provide a legitimate alibi should a crime be committed while the alleged suspect was under surveillance.

Although the best method of placing a suspect behind a keyboard at a specific date and time is visually watching the suspect at a keyboard, it is also the most difficult to accomplish. A simple obstacle such as the computer existing within an enclosed and secure building is more than enough to prevent actually observing a person sitting behind any computer. Physical surveillance also requires intensive manpower and equipment spread across several hours, days, or weeks for a single surveillance operation.

Many times, the result of hours of surveillance is not successful causing frustration. Skill, timing, and luck play important roles in surveillance, but having a plan with surveillance options and contingencies reduces wasted time and increases the odds of completing a successful operation.

This chapter gives the investigator options to consider when planning surveillance operations. The goals of surveillance may be to observe computer user activity at various locations in order to identify potential evidence collection points. Other objectives may include documenting the suspect’s location in order to prove or disprove future claimed alibis or even to apprehend the suspect if seen to be committing a serious violation such as downloading child pornography.

Surveillance operations may be overt or covert, depending upon the desired outcome. Overt surveillance, sometimes known as “bumper locking”, allows the suspect to know he is being followed with an intention to prevent criminal activity. Bumper locking may also be conducted to induce a response from the suspect, such as making phone calls, sending emails, or attempting to dispose of evidence with the goal to collect the disposed evidence.

Covert surveillance, which is the main focus of this chapter, has the goal of watching and/or listening to the undisturbed activities of a suspect to gather intelligence and evidence.

Before initiating any of the options for surveillance, goals and objectives need to be identified. Work schedules, equipment, available personnel, and documented planning take considerable amount of effort before the first operation begins. A thorough background of the suspect allows for a more effective operation. Knowledge of the suspect’s residence, work, associates, and activities beforehand will allow for better planning and successful operations. This information will help the start of the surveillance by knowing where the suspect could be at any given time and may help find the suspect should surveillance lose sight of the suspect.

Mobile surveillance

Mobile surveillance is one of the more commonly used methods of physical surveillance. A mobile surveillance team, riding solo or in pairs in inconspicuous vehicles, simply follow a suspect as he or she travels in a vehicle. However simple it sounds, conducting a mobile surveillance operation that does not alert the suspect requires skill and coordination within the team, relying upon radio communication. The need for fluidity, coordination, and detailed planning increases as the number of surveillance operators is involved.

A single vehicle surveillance operation creates a high risk that the operation will be compromised, or “burned” as a single vehicle will not be able to be out of the line of sight of the suspect. Having more vehicles involved in mobile surveillance allows for the lead vehicle, known as the “eye” to be switched randomly at various locations or turns. The altering of the lead vehicle prevents the suspect from seeing the same vehicle often enough to recognize it during the surveillance operation.

The lead vehicle will also have primarily control of radio communications during mobile surveillance. When the “eye” has been transferred to another surveillance vehicle, the replacement lead vehicle will take primary for radio communications. As long as the lead vehicle has the suspect in a visual line of sight, other surveillance vehicles should not be in view of the suspect to prevent being compromised.

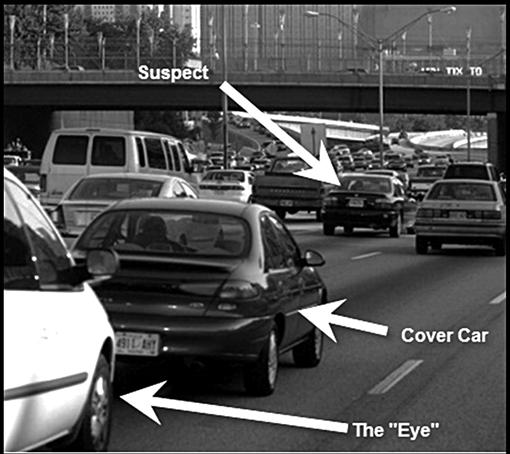

A visual line of sight does not mean the lead vehicle is directly behind the suspect, but rather in a position to have constant and rarely interrupted visual contact, such as seen in Figure 3.1. Normal traffic is used as cover cars, in that other vehicles on the roads are used to cover, or hide, the lead surveillance vehicle.

Figure 3.1 The lead surveillance (the “eye”) vehicle does not need to be directly behind the suspect for effective surveillance and is covered with normal traffic.

Intelligence derived from mobile surveillance should answer questions such as; with whom did the suspect interact, what did the suspect do, where did the suspect travel, which routes were taken, and what are the obvious reasons for each location visited. Having a suspect’s normal activities documented will assist in identifying associates, obtaining sources of information, corroborating information from sources, future suspect interviews, and search warrant planning.

The environment and suspect actions affect specific methods of mobile surveillance. Crowded urban areas with high traffic decrease the ability for the lead vehicle to frequently change as other surveillance vehicles cannot weave through traffic without potentially drawing attention. Rural areas pose a problem of surveillance team vehicles outnumbering the average amount of vehicles on the road, or even being the only vehicles in the area. Suspects that park and enter buildings require that surveillance operators consider leaving their vehicles and conduct surveillance on foot.

To obtain the identity of suspects during surveillance, check the ownership of the suspect vehicle through the Department of Motor Vehicles. This information may be accurate only if the vehicle being driven is owned by the suspect. Another avenue of potentially identifying the suspect is through recovering fingerprints. Should the suspect touch items during the surveillance through eating in a restaurant, it may be possible to recover a glass from the suspect’s table for fingerprinting or possibly from a credit card used to pay for the meal depending upon the environment and potential cooperation of the business.

Internet cafés or businesses that provide access to computer systems are a source of suspect fingerprint identification. Suspects that are seen using a publicly accessed computer system may be checked for the possibility of recovering fingerprints from the keyboard or other items the suspect may have touched and left identifiable fingerprints.

Fingerprints could also be recovered from discarded property in garbage from the suspect’s property after having been collected by the waste management company. Electronic devices used by the suspect and examined covertly or after seizure with arrest or search warrants should be dusted for fingerprints. If for no other reason than to show the suspect actually touched that evidence item, but also to fully identify other potential suspects that may have touched or used the electronic devices.

Potentially, items that the suspect may have used in a crime, such as a hacking incident or sending harassing emails, may be tossed in a public trash receptacle. Surveillance operators that are in the position to observe this activity and recover the items most likely will have collected some of the best evidence in the investigation.

Mobile surveillance may seem to be an overly exhaustive effort for a cybercrime investigation. However, when an investigation requires placing a cybercriminal at a computer, this type of surveillance may be necessary. The benefits of the resources spent on surveillance with expected outcomes as compared with other investigative methods should be considered.

Aerial surveillance

Aerial surveillance affords a near invisibility of investigators for suspect mobile surveillance. Most persons never look up as they travel which makes aerial surveillance one of the best methods to track a suspect’s movements. Depending upon the type of aircraft, ranging from small drones, helicopters, or fixed wing aircraft, the flying height can be virtually invisible to persons on the ground. As can been in Figure 3.2, aerial surveillance covers a larger area with ease as compared to mobile surveillance alone seen in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.2 A greater land area is visible from the air reducing the risk of losing the suspect in traffic.

Aerial surveillance also brings the ability to video record the surveillance. Using infrared (night) vision and thermal imaging cameras, nearly any time of day or night is effective. However, aerial surveillance is rarely even an option for most agencies. Unless the investigation is high profile, the odds of obtaining aerial surveillance support will be low. Even with a high profile investigation, the financial cost per flying hour along with the few aircraft available make aerial surveillance a luxury to which few may have access.

Without supporting ground surveillance, suspect activities occurring within public buildings, such as a coffee shop or shopping mall, will be unobserved from the air. Aerial surveillance in combination with mobile surveillance brings coordination efforts to a new level. Just the communication between air and ground surveillance between different agencies may require a re-configuration or sharing of radios and radio frequencies. Though not to be discounted as a viable means of surveillance, the use of aerial assets does require intensive coordination and resources.

Video surveillance

In an Orwellian surveillance world, all public places would be monitored with video surveillance, documenting every person and all activities. At least the goal of such a Big Brother World of an all-encompassing surveillance system could be so much. Most likely, should any government place such a system into operation monitoring all citizens, public outcry would most likely demand the systems removed.

However, certain systems are already in place by various government jurisdictions. Some of the most common systems currently employed are Department of Transportation cameras along freeways, red-light cameras at intersections, and real-time cameras placed at either high crime or high traffic areas.

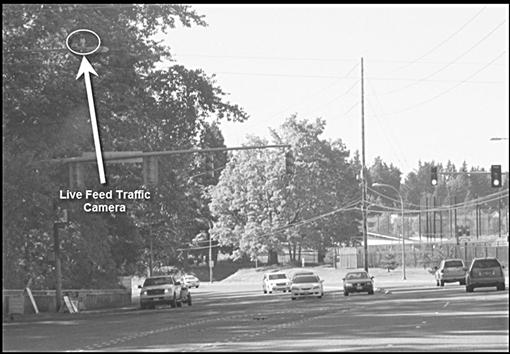

Figure 3.3 shows an example of a real-time (live feed) video camera at a controlled intersection which can capture all traffic. Red-light cameras, that is, those cameras that just take still photos should a vehicle run a red-light, will only capture those vehicles violating a traffic law. The view from the camera in Figure 3.3 can be seen in Figure 3.4. Many of these cameras can pan, tilt, and zoom (PTZ) for more targeted detail.

Figure 3.3 Many controlled intersections are equipped with real-time video and still photo cameras.

Figure 3.4 The video feed from the traffic camera seen in Figure 3.3 (http://www.cityofbellevue.org/trafficcam/).

Government agencies maintaining traffic cameras may allow for public viewing on the Internet, although live streaming video may not be available. Since many of these cameras allow for panning/tilting/zooming, investigators should seek the agency responsible for the cameras in order to gain access to internal viewing, control, and recording.

Although photos taken with the red-light camera most likely are maintained for any period of time, the camera feed for live videos may not be recorded or even constantly monitored. Having internal access to multiple cameras can increase the effectiveness of suspect surveillance with an additional video recording.

To corroborate a suspect’s alleged alibi, obtaining recorded video or photos that might exist should be undertaken quickly. Some systems may retain recordings for weeks where others may only maintain previous day’s recordings. During a suspect interview, locations that the suspect claimed to have been (or not been) may have security cameras to prove or disprove an alibi. This would also include locations where the suspect may have made purchases at gas stations, used an ATM, or other locations with security cameras present.

In addition to cameras in use by government agencies, private companies employ the same technology in more locations for the security of businesses. These locations include security cameras in department stores, gas stations, banks, and even coffee shops. Figure 3.5 shows a commonly used security camera used in many business locations. Businesses with high value property at risk, such as casinos and banks, will not only maintain recordings of the videos, but may also employ full-time monitoring of live feeds to detect criminal activity. As these systems are fairly inexpensive, many businesses employ the security cameras. As an example to the normalcy of security cameras, patrons of most coffee shops hardly pay a glance to the numerous cameras mounted on the ceiling.

Figure 3.5 Surveillance camera typically used in businesses.

The combination of government placed security cameras with private business cameras affords a great amount of coverage of public areas. During mobile surveillance operations, investigators should take note of cameras seen during the surveillance. These would include government cameras on freeways and at intersections as well as private business cameras that surround the perimeter or a business or within the business. A subsequent follow-up to each entity having control of these cameras may recover recorded still images or video of the suspect. These photos and videos would be pertinent documentation of the location, time, and visual identification of the suspect.

Suspects that exhibit a pattern of travel or visits to specific businesses allow for investigators to take full advantage of security camera systems. Given a specific location where a suspect frequents, in which a security system with cameras exist, may present an opportunity for close surveillance without fear of being compromised. Security cameras that are monitored in real-time usually allow control of the individual cameras in varying the angle and magnification.

In some situations, it may be possible to view a computer monitor through a security camera in a public area, such as a coffee shop, as well as record that activity. Figure 3.6 shows an example of a business lobby captured by a ceiling installed security camera. Although the ceiling mounted camera is clearly visible, patrons rarely are concerned or aware of these types of cameras.

Figure 3.6 Surveillance video frame of a business lobby (intentionally blurred).

Businesses cooperating with law enforcement or conducting their own internal investigations can take full advantage of a range of security camera systems. Installation can take place afterhours and be installed specific to monitor a single person or multiple persons. However, there most certainly are limitations as to the extent of surveillance that can be conducted in regard to a person’s privacy, even in the workplace.

Covertly installed cameras

Even as there are private and government owned security cameras throughout public areas in most cities, not every location is covered by a camera. For those areas, investigators may choose to install a security camera specific to the needs of the surveillance. These cameras can be real-time live feeds, monitored constantly or recorded constantly, or configured to take still photos based on programmed schedule or motion detection.

Self-installed systems can be directed at a specific area for a specific purpose. If the suspect activity is suspected to occur at a certain location, such as an Internet Café or a residence, by a specific individual, recording the suspect arriving and departing that location can be matched to later identified acts. A covert surveillance camera can practically eliminate investigators organizing surveillance teams and only requires periodically reviewing the recordings.

Covert surveillance cameras offer more flexibility than overtly exposed cameras. These cameras can be installed in vehicles, such as the classic Hollywood surveillance van, or can be attached to buildings and outdoor fixtures. As one example, Figure 3.7 shows where a covert camera can be installed on a telephone pole or near a power transformer without detection. Issues of personal privacy still need to be considered, even in public areas, as to the legality of placing any device capable of capturing video or photos.

Figure 3.7 A covert surveillance camera can be installed on telephone poles, hidden among standard equipment, without being detected as a camera.

Some criminal investigations require the covert installation of audio and/or video in a suspect residence or vehicle. These instances require court approved search warrants and highly skilled professionals. Covertly entering a residence, business, or vehicle without activating alarms and without leaving traces of having entered is a risky activity. Additionally, nearly any covertly installed device can be discovered either visually or with electronic countermeasures.

Other sources of surveillance records

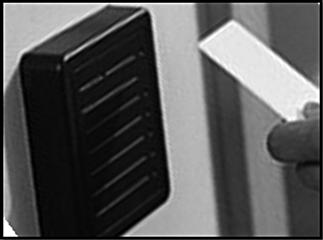

Rather than using keys to unlock doors, many businesses employ access-control systems. Access-control systems assist in tracking employee access to any location of a business location that has an access-device installed. Few are foolproof, but some systems are more accurate and less able to be defeated than others.

One of these security devices is the keycard access system. This system utilizes a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) to control access to secure areas. An RFID chip, about the size of a grain of rice, is usually embedded in a credit card shaped item, a key fob, or other easily carried container. The RFID chip is programmed with the employee’s information and specific security authorization for different access points. The RFID is placed near a receiver that reads the RFID chip. If access authority has been programmed, the door will be unlocked and the action logged by date, time, and user. Without additional evidence, it can only be assumed that the suspect was using the card and not another employee using the suspect’s card. Figure 3.8 is an example of an RFID chip in a handheld, credit card size container.

Figure 3.8 RFID keycard security system.

Businesses with heightened security may usually have additional security measures that not only log employee access, but prevent unauthorized access by those that attempt to portray themselves as an employee. These additional security measures, known as biometrics, can be physical biometrics or behavioral biometrics. Physical biometrics recognition devices rely upon a person’s physical features and include retinal scanners, fingerprint scanners, and facial recognition.

Behavioral biometrics relies upon an individual’s behavior for identification. These include signature recognition, speech recognition, and even keystroke dynamics, where a computer user’s timing of using the keyboard is an identifying factor. Any of these methods contributes to the identification of the suspect and timeline of activity.

Surveillance notes and timelines

Throughout any type of investigation, notes are taken to memorialize events with written documentation. Investigators later transcribe handwritten notes to formalized documents, such as reports, declarations, and affidavits. In addition to these forms of documentation, importing handwritten notes of events into timelines has become a more common method of visualizing a series of events.

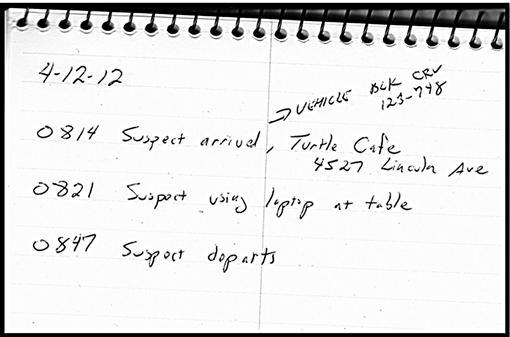

An example of handwritten notes taken from a physical surveillance is shown in Figure 3.9. The format for handwritten notes is usually any form available at the time that an event is observed, even on a scrap of paper if necessary. It is not the appearance as much as it is documenting activity observed to later be transcribed into useful information.

Figure 3.9 Typical handwritten surveillance notes on a notepad.

All persons involved in a surveillance operation are responsible for their own notes. Notes recorded electronically, such as using a digital recorder, should be transcribed to paper. All notes from every person need to be transferred to the case investigator as a central repository of information. In criminal cases, these notes, even the haphazardly written notes on a napkin, are evidence and depending upon agency policy, need to be preserved as such.

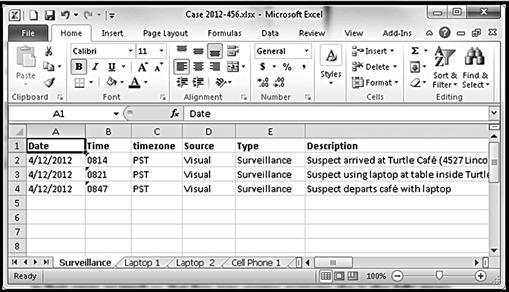

The transcription of notes taken throughout surveillance can be entered into an ongoing timeline of events. Investigators are intimately aware of all information in their cases, so much so, that they may assume everyone else is also fully aware of all information in the cases. The creation of an activity timeline, created specifically to show event, helps to visually describe related activity of an investigation. The transcription of handwritten notes into an investigation timeline is shown in Figure 3.10.

Figure 3.10 Example of transcribing notes from Figure 3.9 into a spreadsheet timeline.

A spreadsheet is perhaps one of the easiest methods to store events. A database will have more capability to store more information but the ease to which a spreadsheet can be more quickly created and shared with other persons. A spreadsheet timeline can be sorted by any sorting column to find information or view specific information. Events can be entered in the order received, not necessarily as they occurred, yet the timeline can be sorted by time of event quickly.

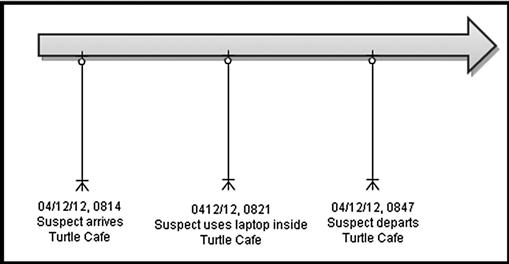

A visual representation using the sample information from Figure 3.10 is seen in Figure 3.11. Case presentation methods involving massive amounts of data from forensic analysis and physical surveillance operations will be detailed in a later chapter. But, it will be helpful to keep in mind the reason for keeping track of all events, even events that may seem inconsequential, for later analysis and case presentation. One of the end results of constantly working on a timeline is the visual representation of physical suspect activity and computer activity across a multitude of devices and locations.

Figure 3.11 Simple example of creating a visual timeline of activity.

Complex cases will have complex visual representations. Copious notes and voluminous phone records will add to this complexity. Organization skills are a valued trait in these types of investigations, especially when event information from multiple electronic devices is merged with surveillance activity notes.

Electronic Surveillance

Nearly all surveillance methods noted in this book are available without legal authority such as a search warrant. Both licensed private investigators and law enforcement can follow persons in public without hindrance in furtherance of their investigations. Businesses can place cameras in openly public areas of their property for security purposes. However, electronic surveillance, as it pertains to obtaining private information, is conducted only by government agencies with the appropriate legal authority granted to them for each circumstance. This type of electronic surveillance includes technology such as wiretaps to covertly capture the spoken word of any and all parties of a phone or electronic communication conversation.

Several of the electronic surveillance methods detailed in this section require authority granted by a court order, search warrant, or subpoena (administrative, grand jury, or trial). Depending upon the state, certain methods may not be approved at all. The investigator needs to be aware of local, state, and federal laws when considering employing electronic surveillance due to the possibility of carelessly committing a criminal offense in the process. Other methods are clearly available to any entity as long as the personal privacy of individuals is not violated. When in doubt, ask for legal advice. Even if not in doubt, asking never hurts.

Oral intercepts

The most publicly well-known type of electronic surveillance authority is the wiretap, also referred to as Title III (Federal Wiretap Act). The Title III is not found in the United States Code under “Title 3.” It is actually under Title 18. Title III refers to the title number in Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 which is Title III. Some states, such as California, also allow for wiretaps conducted by local law enforcement. The wiretap of oral communications requires a high burden of necessity for approval, usually because other investigative means are shown ineffective or expected to be ineffective. Some states, such as California, approve wiretaps only as the last resort.

Wiretap authority applies not only to the interception of telephones and cell phones, but also real-time capture of text messages, email communication, and Internet Relay Chat through network monitoring and use of Sniffer software. Sniffer software are programs that intercept routed data and examine each packet for information such as passwords and other data transmitted in clear text. Sniffer software can be configured to capture specified data or targeted data, depending upon the needs of the investigation.

Wiretaps are an extremely effective means to collect evidence in real-time, capturing the actual spoken words of suspects. Wiretaps also require intensive resources, both in personnel and finances, but as mentioned, may be the last resort in some investigations. An important note with wiretaps is that it is usually the suspect and all the communication devices used that are authorized for a wiretap. As it is common for criminals to use disposable phones, roving oral interceptions are approved to cover for the devices used.

Dialed number recorders

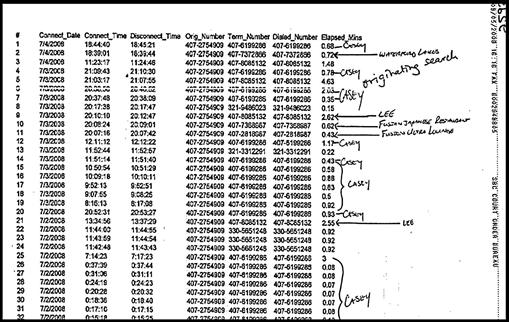

Pen Registers and Trap and Trace devices are electronic devices that record all outgoing and incoming information from telephone calls and Internet communications. Practically, a Pen Register records outgoing numbers with the Trap and Trace device recording incoming numbers. More accurately, the devices can be called Dialed Number Recorders (DNR). The type of information captured is in the form of dialed telephone numbers, the length of calls, and the identities of an email message’s sender and recipient. Although the content of phone calls and emails is not captured, intelligence can be derived by the capture of this information and merged into a case timeline.

An example of phone records, also known as “phone tolls,” is seen in Figure 3.12, from State of Florida v. Casey Marie Anthony (2011). Cell phone records, showing calls/text made and received, combined with cell tower analysis, can give indications of suspect location. Further investigation of phone records, such as interviewing those listed communicating with the suspect phone, may confirm that the suspect possessed the phone, discrediting a suspect’s claim that someone else possessed the phone.

Figure 3.12 Phone tolls from the Casey Anthony murder investigation.

Identifying a suspect’s cell phone is problematic unless the cellular number is publicly available. When the cellular is not publicly available, or the suspect frequently changes cell phones, law enforcement can obtain the numbers through use of a device known as the “Triggerfish.” The Triggerfish device mimics a cell phone tower. By being seen as a cell phone tower by cell phones in the area, or an area targeted by the Triggerfish, the cell phones will reveal their phone numbers, serial numbers, and location to the Triggerfish device. Neither the cell phone nor cell phone tower is alerted to the use of the Triggerfish.

A Triggerfish was used in the capture of one of the world’s most well-known hackers, Kevin Mitnick (Shimormura, 1996). Mitnick’s hacking career started when he was 16 in 1979 and continued until 1995, where he was arrested and convicted and served over 4 years in prison.

The Triggerfish also assists in obtaining cell phone information for Dialed Number Recorder (DNR) applications and wiretaps. The need for a DNR in an investigation can be determined in the same manner as any investigative method. Will it be beneficial to the investigation? Are there other more effective methods? Does this method pertain to the suspect’s use of cellular phones? What legal authority is needed?

Residence landlines are a source of information that can also corroborate a suspect’s location. Retrieving records from the phone service provider will show calls made and received by the home landline. Interviews with the owners of numbers listed in the records may be able to confirm that the suspect used the phone in question on a specified day. Claims that a suspect was not at home during an incident, such as the downloading of contraband on a home computer, may be able to be disproven through phone records, even though no physical surveillance was conducted. A partial listing of home phone records from State of Florida v. Casey Marie Anthony (2011) can be seen in Figure 3.13.

Figure 3.13 Home phone records from the Casey Anthony murder investigation.

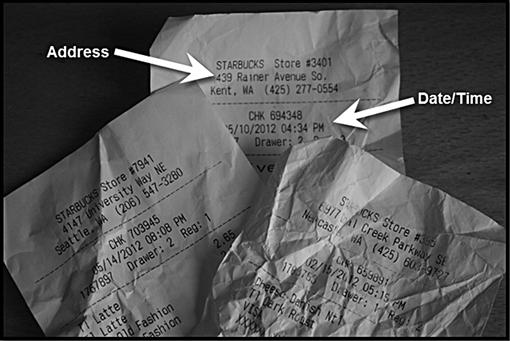

Trash runs

The legality of collecting another person’s trash from the curb varies state to state, and federally. If legal authority exists in which investigators can collect the suspect’s trash, evidence obtained from the trash may be able to place the suspect at various locations. Examples would be finding receipts from locations that provide access to wireless networks such as a café. An example of such a fantastic find is seen in Figure 3.14.

Figure 3.14 Example of “trash” that can place a suspect at a specific location at a specific date and time.

The significance of evidence that can be recovered from trash is that purchases made in cash, in which the suspect kept the receipt only to throw it away, would not be found through a search of bank records or credit card purchases. Even with multiple persons living at a single residence, receipts and other items placing a person at a location will be beneficial to the investigation. Many investigations are solved through pure luck. Timing plays a part. Skill plays a part. Suspect mistakes also play a part. But in many cases, it seems as if pure luck breaks a case.

In the example of finding receipts with dates, times, and locations that provided wireless access, if there were IP addresses previously obtained that were identified used in criminal activity result that matched, then luck in finding these receipts could break the case. Potentially, store video could be obtained based on thrown away receipts. The term “luck” is used loosely as good investigators seem to be lucky all the time when in fact, it is just hard work and tenacity.

Tracking cell phones

For a cell phone to be able to make and receive calls, it must communicate with cell phone towers. As a cell communicates with cell phone towers, the provider of the cell phone service generates a log of the connections. The phone service provider maintains those logs of communication with the cell towers for a length of time. The retention of data varies with providers, but most times will be available for at least one or more billing cycles.

Cell phones with Global Positioning System (GPS) enabled can be tracked remotely, in real-time. Currently, there are few, if any cell phones being manufactured without GPS capability. Corporate owned cell phones can be tracked by GPS and monitored online by the owner, just as a corporation can employ GPS on its fleet vehicles. The corporate monitoring of physical assets is conducted without the need of court approved search warrants.

Obtaining and analyzing cell tower records allow the investigator to track the movements of the phone through a given time period, nearly like a Global Positioning Device would. Investigators can plot the communication with cell towers on a map, and if the device can be tied to the suspect, it can be assumed that the travel of the cell phone was similarly that of the suspect.

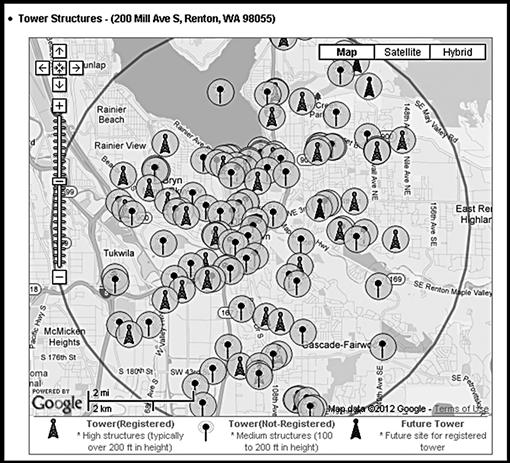

Cell tower information accuracy depends upon various factors. The type of tower, number of towers in the area, terrain, buildings, weather, and even the time of day will affect the accuracy of location. There are numerous online sources to find locations of towers based on location. One such website is http://www.antennasearch.com. The results for cell towers for 200 Mill Ave S, Renton, Washington returned the following visual representation of cell phone towers seen in Figure 3.15. As can been seen in the visual, there are many towers for which the suspect cell phone could communicate with better accuracy than locations with fewer cell towers.

Figure 3.15 Results of a tower search http://www.antennasearch.com.

Cell tower analysis contributes to physical surveillance efforts. Relying solely upon cell tower analysis does not confirm the suspect possessed the phone, only the location of the phone itself. Potentially, any cell phone may be shared or even inadvertently forgotten in another person’s vehicle and recovered at a later time by the suspect. Combined with other surveillance methods, a cell tower analysis can corroborate intelligence gathered throughout the investigation as to the whereabouts of the suspect.

Vehicle tracking

Installing a GPS device on a suspect vehicle allows for constant monitoring without fear of losing sight of the vehicle with mobile surveillance. Combined with an identified cell phone belonging to a suspect, movements can be tracked using cell tower analysis of the cell phone which can result in surveillance resources able to be curtailed.

As with any electronic surveillance method, investigators must abide by the current law in their jurisdiction, which will change as technology changes. There are different methods to employ GPS on vehicles. Attaching a GPS device can be either magnetic (“slap on”) or hardwired to a power source on the vehicle. The use of the GPS and ease of covertly installing the device usually determines the type of installation.

Depending upon the GPS device, information can be stored and not transmitted or data can be transmitted wirelessly for real-time review. For regularly transmitted GPS data, which can be once every second to any time afterward, the power needs for the GPS will be higher. Wireless transmission configuration is best when the GPS is hardwired to a power source from the vehicle.

GPS units that do not transmit data usually require the investigator to manually recover the data by either connecting to a computer or be within a close distance to connect with a short-range wireless connection. If a suspect is identified as renting a vehicle that has GPS installed, obtaining the data after the vehicle is returned could lead to pertinent location information.

As newer vehicles have options for factory installed GPS systems, the ability to remotely activate (if not already activated) the vehicle’s onboard GPS system exists. However, having access to the suspect’s GPS system could potentially be compromised due to factors such as the suspect activating or deactivating the GPS through the provider of the service.

GPS devices are also becoming common for home detention, where a person convicted of a crime such as drunk driving, may opt to serve their jail sentence at home, and agree to wear a GPS device. This allows for the person to travel between work and home while under electronic supervision. These GPS devices most always transmit real-time data, accessible by the agency responsible for monitoring the persons.

Automated toll collection devices are a source of location information for a suspect’s vehicle. These toll collection devices will log the vehicle’s date, time, and location for billing purposes. Automated toll collection data collection can be in the form of scanning license plates using cameras or through Radio Frequency Identifying devices (RFID) attached to vehicles. This information is available from the billing third party and can add to the suspect’s location.

Another method to determine historical locations of a suspect and vehicle is through a check of the suspect’s driving record. Traffic stops by any law enforcement agency that issues a citation will be entered into the suspect’s driving record. Even if a citation was not entered, should the traffic officer check the driver’s name for wants and warrants, this information may be available for some time. Traffic stops have placed suspects in close proximity to crimes for many years. A classic example of a common traffic stop resulting in the arrest of a suspect is the case of United States America v. Timothy James McVeigh (1997), bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building Oklahoma City, where one McVeigh was identified through a traffic stop shortly after the bombing.

Keystroke logging

The installation of keyloggers will almost always require the authority of an approved search warrant. A keylogger may be a software program that covertly logs selected or all keystrokes or it may be a hardware device connected to a computer system to collect keystrokes. Either system requires installation on the suspect computer system in a covert manner. Hardware keyloggers, disguised as a keyboard connection adaptor, must be physically installed by attaching the adaptor to the computer.

A software keylogger program must be installed as any other software program. Both of these methods inherently cause a risk of compromise with the initial installation since physical access to the computer system is needed. Software keyloggers can be installed remotely through an email or other network connected means.

Hardware keyloggers pose a risk of discovery only if the computer user inspects the connection of the device, such as when replacing a keyboard or mouse. The computer operating system is not able to detect a hardware keylogger as the device does not interact with the system. Software keyloggers may be detected by anti-virus software, which would immediately disclose to the suspect compromise of the computer system.

Sophisticated computer user logging software not only captures keystrokes, but also captures screenshots, all of which may be covertly sent to investigators for remote viewing. It is also possible to remotely access the entire system of the suspect computer, at the operating system level and physical level without alerting the suspect. This access allows for forensic capabilities to search for specific data or recover deleted files remotely. However, to gain remote access, the system needs to be compromised through the installation of these programs through an email or having physical access to the suspect machine.

With the use of the on-screen keyboard, where a keyboard is literally displayed on a computer monitor, keystrokes are actually mouse clicks on this virtual keyboard. Keystroke monitoring software may log the mouse clicks, but not the letters or numbers clicked on the virtual keyboard with the mouse. The use of a virtual keyboard to log in to password protected accounts renders a keystroke logging software useless.

Several cases have been successful with the use of keyloggers. One such example is case, United States of America v. Nicodemo S Scarfo and Frank Paolerico (2001). In this particular case, the suspects were employing encryption programs to protect their electronic communications. The FBI obtained approval to install a keylogger to log passphrases used in encrypting communication. Through the use of this program, the FBI had access to passphrases needed for email accounts and encrypted files.

Consumer purchase records

Once a suspect’s activities have been detailed to some extent through surveillance and other information, locations which are frequented may be of a great resource. Shopping clubs, gyms, hotels, grocery stores, and other locations where the suspect may make purchases when using a membership card can yield historical information that may be of value.

Obtaining and analyzing credit card purchases quickly lead to past suspect locations for each purchase. Many locations, such as gas stations, will maintain video surveillance records for a time period. To place a suspect in an area of activity, the use of a credit card combined with a video surveillance of the purchase will be best evidence. This type of information can be used to corroborate an alibi if a suspect denies having physical access to a computer system if it can be shown through purchase records or video surveillance records.

Real-time monitoring of a suspect’s credit card purchases may also provide investigators with potential leads to a crime in progress. Should a known cybercriminal regularly visit a location to use an open wireless connection, any purchases made could be indicative of using that wireless connection again for a crime.

Obtaining Personal Information

Aside from government maintained personal information on suspects, which is in the form of criminal history and arrest data, publicly available information is well suited in increasing surveillance operations. With the Internet becoming an integral part of our lives, personal information has become widely available online. Surveillance of suspects via the Internet is not only easier on resources, but is effective.

Perhaps the most important reason to gather suspect information from online (public) sources is to determine current suspect activities, behaviors, associates, and physical locations. By having a list of frequented locations, surveillance can be enhanced. Routes from the suspect residence to known locations can be scouted as can the actual locations. Surveillance operators can be inserted into known locations prior to suspect arrival and greatly decrease risks of surveillance being compromised.

As an example, with social networking websites, notices of events are posted and shared openly. Should a suspect be known to attend any event, surveillance operations can plan to begin surveillance at the expected location rather than starting from the suspect home. This decreases the odds of surveillance compromise as the suspect will not be followed from his residence. Additionally, if a surveillance operator has been positioned in the location, even as an attendee, the suspect’s awareness should be lower than having had been followed.

Information gained online may be used to discredit claims by the suspect at some point. Membership and attendance at computer-related clubs would help discredit claims of being computer illiterate. Claims of not having access to a laptop or portable device would be discredited should the suspect be seen carrying or using a device to a meeting or conference previously identified.

Other information gleaned from online sources may be actual evidence to be used in the investigation. Forums, blogs, and comments attributed to the suspect that detail criminal activities should be preserved immediately before disappearing from the Internet. A number of motives may be able to be found among suspect postings on the Internet, such as displeasure with the government, business, or particular person. Suspects may even reveal information concerning sources of evidence such as detailing purchases and use of computer systems.

Placing the suspect behind a keyboard is possible through an online search for that user’s Internet activity. Postings to blogs and forums are usually tagged with the date and time of the posting. Attributing a user account to the suspect, or any number of user accounts to any number of blogs or forums, can lead to a timeline of computer activity by the suspect without the investigator having physical access to the actual suspect computer. Although it is possible for a suspect to arrange for postings to be made in his behalf, the general assumption is that the suspect is making the online postings.

For any websites or blogs with suspect comments or posts, search warrants or subpoenas would be a good investigative method to use in order to obtain the originating IP addresses of the postings. Tying the suspect to an IP address, which may even be corroborated with physical surveillance, puts the investigator that much closer to placing the suspect behind a particular keyboard.

Most social networking sites allow users to upload photos. There are also a number of websites that are specifically designed to solely upload user created photos. As digital photos may contain embedded geographical location (“geo-tagging”) metadata, investigators may be able to determine not only the date and time a photo was taken, but also the location. This feature is turned on by default in many cell phones and users are sometimes blissfully unaware of the embedded locations.

In 2012, the FBI identified and arrested a notorious criminal hacker, Higinio O. Ochoa, through a photo posted online that contained geographical location in the metadata. The photo of Ochoa’s girlfriend was taken using a cell phone camera, with GPS indicating a location in Melbourne, Australia. Through an investigation of other related photos found online, Ochoa was identified through his girlfriend’s GPS location and posts on the Internet. The main point of this example would be that even the most experienced cybercriminals will make mistakes allowing for their capture.

Undercover and Informant Operations

Undercover operations in cybercrime investigations obviously will include use of electronic communication. Undercover (UC) agents email, text, and chat with suspects online to communicate. This can be in the form of the UC assuming the identity of a child to investigate child molestation cases or perhaps the UC will assume an identity of a high-tech criminal to investigate a hacker. Either method can require face-to-face interaction between the UC and criminal suspect. This interaction and investigative method will apply similarly to civil investigations.

A great example of a successful undercover operation began in 1999 with the Internet Service Provider (ISP), Speakeasy Network, in Seattle, Washington. The Speakeasy Network was hacked from Russian IP addresses. The suspects contacted Speakeasy, identified themselves, and offered to not disclose Speakeasy’s flaws if Speakeasy would pay or hire them. The hackers also claimed to now possess thousands of passwords and credit card numbers from Speakeasy customers. These hackers, Alexey Ivanov and Vasily Gorshkov, continued to hack and extort businesses in this manner.

The FBI conducted an intensive undercover operation, in which both Ivanov and Gorhkov agreed to enter the United States to discuss their hacking skills with FBI undercover agents. Through audio and video recorded conversations, keyloggers, sniffers, search warrants, undercover business fronts, and even setting up an undercover computer network for them to hack into, both were convicted on federal felony counts of computer fraud, mail fraud, and conspiracy.

All undercover operations carry an inherent risk to personal safety. As an investigative method, it also carries a need for intensive resources and skilled UC operators. The effectiveness of a successful undercover operation cannot be overstated. A benefit to being able to speak openly to a suspect while assuming the role of a criminal or conspirator allows for intelligence to be gathered exponentially faster than physical surveillance. Confessions made to an undercover are just as valid as a confession made to a uniformed officer. Future suspect activities, something not easily obtainable otherwise, can be spoken directly to the UC to which future operations can be planned.

Less extreme undercover activities can be conducted requiring no more than a phone call. If a specific time and place has been identified as a source of criminal activity, a simple phone call to the suspect will place the suspect at the location at a given time. The phone call need be no more than false pretenses in which the suspect is identified by voice or name. The phone call may not definitely place the suspect at a keyboard; however, tying the suspect to the location by voice is a strong indication. For criminal activity in progress, such as a victim receiving harassing emails from a previously identified location through an IP address trace, a call can be made while the activity is occurring to identify the suspect by voice.

If a suspect email address has been identified, emails can be sent to the suspect with a tracking code that obtains the local IP address of the suspect, and then sends the date and time of the email being accessed along with the IP address of the suspect computer. These tracking codes are invisible to most users and email programs, but pose risk of compromise should the code be identified by the suspect through a warning from anti-virus software.

Undercover operations coupled with surveillance may also be necessary in order to obtain evidence not able to be obtained otherwise. If a suspect obscures his IP address through any means, without having physical access to the system used in crimes, close contact with the suspect may be required. This contact could be in the form of befriending the suspect in hopes of having information disclosed to the UC. Even only if the manner of hiding the IP address was disclosed, investigative methods to counter the IP address hiding method could be conducted.

Informant operations pose the same risks to safety and compromise of the investigation with the added danger of informants being untrained. Informants have varied reasons for cooperating with law enforcement and not every reason is trustworthy. In many cases, informants are developed from cases, in which the arrested suspects agree to cooperate in consideration for lesser charges. Such was the case of Hector Xavier Monsegur, in June 2011, when he was arrested by the FBI. Monsegur agreed to work for the FBI as an informant, and in doing so, helped the FBI successfully investigate multiple hackers as conspirators. Although Monsegur did agree to cooperate, he also pleaded guilty to a multitude of computer crime charges.

Probably the biggest benefit to using informants in a cybercrime investigation is being able to take advantage of this past history and contacts with other cybercriminals. Their reputations may be known and few, if any associates would suspect their long-time partner-in-crime to be working for law enforcement. Undercover officers enter without a history or known accomplices, unless an informant is used to vouch for the undercover officer.

Witnesses

A witness may be a rare find, depending upon how you define what makes a witness to cybercrime activity. Practically, a witness would not only have access to viewing a computer monitor, but would have to identify the activity on the monitor as nefarious. Still, with a witness placing a person at a particular computer at a particular time, the investigator’s determination that a crime had occurred negates the witness having knowledge of witnessing a crime.

Witness identification has drawbacks and potential dangers. Essentially, a witness can wrongly identify a person. Wrongly identifying any person that cannot provide a legitimate alibi has resulted in persons being convicted for crimes and later absolved. A single witness may be the most important evidence factor in the identification of a suspect in an investigation, and as such, investigators need to be aware of the potential of falsely identifying someone. The selection of a suspect by a witness when presented a montage of photos or a lineup has the potential of outside influences affecting the selection. The verbiage and tone spoken to the witness by investigators, the selection of individuals used in the lineup or photo montage, and even the mannerisms that are subconsciously exhibited by investigators can influence the witness.

At a minimum, when using lineups or photo montages, the person presenting these to the witness should not know which individual is the suspect. The persons chosen in a lineup or photo montage should be of similar appearance to each other and the certainty to which the witness decides should be documented in detail. Outside factors that affect the witness which cannot be controlled include the duration and conditions to which the witness observed the suspect.

In the corporate environment, witness identification is more certain and rarely requires the need for photo montages or lineups. This is due mostly to witnesses personally knowing or observing the suspect in their workplace. A corporate witness can testify to the number of different persons that have been seen accessing a specific computer system and probably identify each of them by name. As the witness may not have been knowingly observing criminal activity or policy violations, the witness may be able to at least place a person at a computer system at a given date and time.

Neighbors as Surveillance Agents

Depending upon the surrounding environment, surveillance of a suspect’s residence is typically not a difficult task. But, there are instances where surveillance may be impossible due to a multitude of factors, such as existing in remote location. The investigator can consider contacting a neighbor of the suspect to assist in surveillance. The risk of using any citizen is that the surveillance and investigation may be intentionally or accidently disclosed by the neighbor.

Depending upon the severity of the investigation, in which violent offenders may be involved, neighbors may be placed at risk when asked by investigators to watch their neighbor. Confrontations between the suspect and witness neighbors also increase the risk of compromise especially for any neighbor now believing to have police powers.

At times, a neighbor may be the most reasonable, or only, option, but rarely is it the first option to consider. Usually, neighbors are best contacted afterward in search for historical information they may have observed about the suspect. Having citizens engage in active investigations without constant supervision incurs a risk of the investigation becoming compromised inadvertently.

Deconfliction

Law enforcement officers regularly “deconflict” with other law enforcement officers to avoid compromising investigations and increasing officer safety. Deconfliction is conducted by contacting a central repository of criminal investigations. Nearly all cases are naturally deconflicted internally within an agency simply due to have a centrally used reporting system within the agency. Informally, the investigating agency may contact surrounding agencies for information on suspects and investigations on those suspects.

The most effective and widely used law enforcement deconfliction method is provided by the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA). Figure 3.16 shows the HIDTA website where law enforcement can contact for more information and access to the Watch Center. HIDTA operates the “Watch Center,” a central repository for all law enforcement agencies to submit case or event information. This information includes specific suspect details, case details, and current operations, which is used to cross check against other law enforcement agency submittals. If the Watch Center discovers a match on any event, person, or case between any agencies, those agencies are notified by the Watch Center to coordinate the exchange of information.

Figure 3.16 The HIDTA Watch Center website, http://www.hidta.org.

In this manner, law enforcement agencies can either pool resources together for related investigations or the agencies can share the information for more effective law enforcement cases. Having access to past investigations, to include surveillance notes of suspects, may not only save time on subsequent surveillance operations, but also could help determine the methods used by suspects more quickly. The benefit is mostly because the work may have already been verified, corroborated, and documented by another agency for you.

Summary

Physical surveillance, including electronic surveillance, can be an extremely labor-intensive and risky investigative method and requires training for safety and success of the operations. In many cases, it is also required to compile a thorough investigation. Investigators must constantly be aware of the digital crime scene as it interacts with the physical crime scene. Although law enforcement has options not available to non-law enforcement, the abundance of techniques possible should suffice for the majority of investigations.

The process to build a timeline of activity for a case, whether criminal or civil, should take into account the activity of suspects while they are not only behind a computer, but when they are not near any computer systems. As the goal of all investigations is to find the truth, as much intelligence gathering as possible should be completed to accurately identify the suspect.

The culmination of information gathered during the surveillance phase of investigations can be integrated with information collected during the forensic analysis of electronic media to create a complete picture of events.

Bibliography

1. Shimormura T. Takedown. New York: Hyperion; 1996.

2. State of Florida v. Casey Marie Anthony (Ninth Judicial Circuit of Florida. 2001).

3. Todd M. Chism, individually and as husband and wife, Nicole C. Chism, individually and as wife and husband v. Washington State; Washington State Patrol; Rachel Gardner individually; John Sager, individually. (Court of Appeals for the Ninth Cir. 2011).

4. United States of America v. Nicodemo S Scarfo and Frank Paolerico (US District Court 2001).

5. United States of America v. Timothy James McVeigh (US District Court 1997).

Further reading

2. Title III of the Omnibus Crime and Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (Pub. L. 90-351: 6/19/1968).