Putting It All Together

Information in this chapter

“2 + 2 = Putting it all together”

This chapter gives tips for identifying the suspect as well as eliminating possible suspects by helping develop your investigative mindset. Investigators and forensic examiners can easily become extremely focused on a specific person or incident. So much so, this extreme focus may prevent understanding the totality of the investigation. Incorrect assumptions, false investigative leads, or erroneous conclusions can turn an investigation into a train wreck where the guilty goes free and in worst case scenarios, innocent persons are wrongly accused. These incidents can happen when investigative goals and objectives are not clear.

The tips in this chapter show methods of compiling information to weed irrelevant data to develop a suspect list. Many of the methods used to develop a list of suspects can be used in presenting these facts of the case in legal hearings or internal review boards. Particularly in larger investigations, it will benefit the investigator in maintaining a structure of data organization throughout the case.

In those cases where a suspect will admit guilt, many of these concepts to identify the suspect may not even need to be employed. But sometimes, to obtain an admission of guilt, analyzing all information is needed to ask the right questions to obtain the truth.

Reconstructing the crime scene is a scientific process. Evidence needs to be identified, collected, and analyzed. Persons involved in the incident, including witnesses, need to be interviewed. Beyond the scientific method, investigators need to consider that creativity plays a large part of solving any crime and sometimes, that is the most difficult trait to teach. The following methods are intended to spark creativity.

The evidence as a whole

The seriousness of the incident coupled with the time and resources available directly impact the amount of evidence collected. That just means important cases usually have more evidence and less important cases have less effort used. This is simply a matter of prioritizing the case load for effective time management.

An example to a case with minimal evidence would be the deletion of one document from a single laptop in a civil litigation case. This case may require only one analyst to recover the deleted document from the laptop. Conversely, a criminal organization that creates and globally distributes child pornography across the Internet will require substantially more resources resulting in a massive set of evidence, both physical and electronic. Each investigation determines resources needed and the evidence to be collected.

Whether the evidence consists of a few items or an entire storage locker of physical evidence plus external drives containing terabytes of electronic evidence, looking at the items individually is just as important as looking at all the items as a whole. Items collected that initially appear to be irrelevant may be able to corroborate relevant evidence or give additional leads. One example would be employee timecards, where a suspect appears to have been at work at the same time user activity occurred on his home computer.

On the face value of the timesheets, this would suggest that another person was at the computer, or perhaps, it could have been remotely accessed by the suspect at work. Either way, further investigation is required rather than jumping to conclusions that the user account name is also the suspect’s name.

Every criminal act or corporate internal violation of policy involving electronic storage devices involves at least two evidence processing scenes; the devices used (the electronic crime) and the location (the physical crime scene). From that point, there may be additional electronic crime scenes on just one or maybe thousands of victim computers. Looking at all crime scenes overall as one incident helps put a puzzle together of how each scene interacted with another.

Avoiding assumptions

Sometimes, guesses are correct without corroborating evidence. Assumptions made without corroborating evidence can be correct. Then again, assumptions are akin to guessing and the odds of being wrong are too high to risk making substantial decisions on guesswork. Even when all scientific evidence points to a specific person, there is always the chance of an innocent person being framed for a crime. An example can be seen in United States v. Barry Vincent Ardolf (2011), involving an incident between two neighbors in which an innocent person was framed for crimes by a neighbor. The neighbor, Barry Ardolf, bypassed the wireless security settings of the victim’s Internet router.

After gaining access to the wireless router of his neighbor, Ardolf accessed the victim’s computer systems and conducted criminal activity that appeared to have been originated by the victim. Child pornography was not only downloaded to the victim computers, but Ardolf created and used emails in the victim’s name to send child pornography to others and sent death threats to the Vice President of the United States. The victims cooperated with the Secret Service by allowing the use of sniffer software applications on the victim’s wireless network. The analysis of captured Internet packets led to identifying Ardolf as the real suspect, leading to his conviction and 18-year prison sentence.

The importance of this example cannot be overstated as the victim did use encryption on the wireless network, which was bypassed within 2 weeks by the suspect. All evidence prior to capturing Ardolf’s access to the victim network pointed directly at the victim. This case of wrongfully targeted citizens based solely on an IP address is a too common occurrence and can be avoided through additional investigative work.

Who did it?

Skilled forensic analysts and investigators are great when they not only determine the computer user activity of a suspect, but also answer the basic investigative questions of who, what, when, where, why, and how. The answer to one question may only be derived by answering another. The answer to who committed the act may be derived by answering the question of why someone would commit the act. As important with every forensic analysis to determine what happened and how it happened, it is just as important to find other answers to determine who did it.

Unfortunately, it may be practically impossible to determine the person that was behind any keyboard based solely on forensic analysis. With exceptions such as biometric logging devices, the electronic data recovered from any computer simply shows that certain keys were pressed on the keyboard at certain times causing specific activity to occur with or on the computer. Unless the computer system is creating a video capture of the computer user and saving that video locally to the machine, any person can be at the keyboard without additional circumstantial evidence. As this is rarely the case, traditional investigative methods and creative thinking need to be engaged.

Motive and opportunity

There are certain crimes and incidents in which determining the motive and opportunity may quickly solve the investigation. A defendant receiving a legal preservation notice to preserve an electronic document which is later discovered to have been deleted has motive. If the electronic document existed on the defendant’s computer hard drive, the opportunity also existed. As long as there are no other factors such as multiple persons having had access to the previously deleted electronic file, a primary suspect may have been identified quickly and easily.

This becomes more complicated as opportunity has become almost effortless due to the interconnectivity of computer systems. Opportunity does not necessarily require physical access to an evidence computer system, which greatly increases the possible list of suspects through remote access.

Multiple persons may have different motives in the same incident, whether the motive is to hide evidence through the destruction of electronic data in a business or perhaps a conspiracy of persons to profit through online fraud. Investigations many times will show that more than one person had both different motives and multiple opportunities. Because of that factor, without additional information, a suspect can be overlooked or innocent persons being accused with suspects.

Hidden motives may be more difficult to determine in some cases. Such would be the motive to profit from a crime. Profiting financially is obviously a motive, but a hidden motive may not be so obvious. A hidden motive to profit could be for a drug addiction problem, late bills, revenge, or to pay for a luxury vacation. A motive to profit without specifics may not be enough to show motive for a specific person and sometimes, the only motive needed by a suspect is “just because.”

Process of elimination

One of the most effective means of identifying a suspect and placing the suspect at a scene is through the process of elimination. Of course, a list of possible suspects needs to be identified first and that is not possible in every case. A civil litigation investigation in which all activity occurred within a corporate network will be easier to develop a list of suspects based on known employee access to electronic devices. An intrusion conducted using anonymous proxies may be close to impossible to develop any identifiable persons without further investigation and even with additional investigation, may still be impossible.

A combination of physical investigative methods, such as surveillance and interviews, plus the analysis of electronic devices and call data records can be used to create and narrow a list of suspects. Given any number of suspects, call data records can place their cell phones at specific locations by date and time. Analysis of their workstations and personal computers can show user activity that may be attributed to their use.

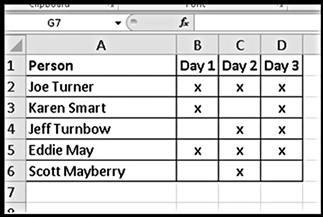

Having a long list of suspects requires effort to eliminate names; however, this is a better scenario than not having any possible suspects identified at all. Charts and spreadsheets are effective in keeping track of possible suspect names and helpful in visually identifying relationships. A simplistic example of creating a list of suspects is seen in Figure 5.1. In this example, where there are 3 days of activity in question, each possible suspect has been noted for each day of having physical access to a shared business computer system. This type of technique is also known as a matrix chart.

Figure 5.1 Example of a matrix chart used to identify suspects and their activity.

Complex investigations involving multiple storage devices and systems do not automatically make such a list as Figure 5.1 complex. It is quite the opposite in that the more incidents in question, fewer persons will be able to have accessed a shared machine over a long period of time for all of the incidents.

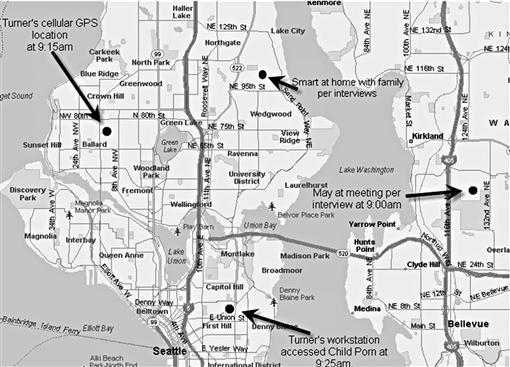

Plotting geolocation data obtained from investigative sources onto a map creates a visual representation that is helpful in eliminating or identifying persons as suspects. An example seen in Figure 5.2 shows three identified persons with their locations and one location where the investigated incident occurred at 9:25 am on Turner’s workstation. Assuming the persons were located as noted, either an unknown person used Turner’s workstation at 9:25 pm locally or it was accessed remotely by an identified person.

Figure 5.2 Plotting locations of suspects in relation to an alleged incident helps to place suspects at the scene while eliminating possible suspects if they are placed elsewhere.

Geolocations of all suspect controlled devices can be plotted by date and time, showing travel and use. The traveling laptop of a suspect that matches the geolocation of the suspect’s cell phone records strongly implies the suspect had control of both items at the time unless reported stolen or loaned to another person.

Shared computer systems used in an incident, whether criminal or civil, pose problems in tying a single person to the acts, especially if there may have been several persons using the system as conspirators. In a corporate setting, individual workstations might be physically accessed by any person in the building if security measures are not employed. In those types of cases, a detailed investigation into the whereabouts of all employees may be required including interviews and potentially, examination of their individual workstations in order to determine user activity that can place them at a specific spot.

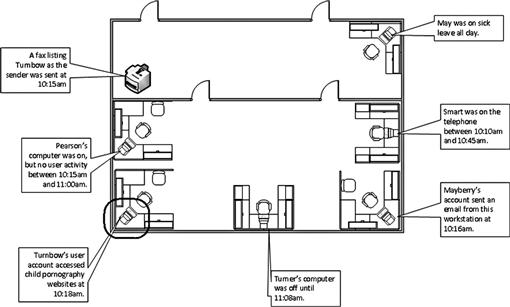

A diagram of an office is shown in Figure 5.3 depicting multiple persons potentially being suspects in illegal computer use. There are six persons with physical access to every workstation in this sample office. In this example, employee Turnbow’s workstation accessed child pornography at 10:18 am, however, a fax was also sent listing Turnbow as the sender at 10:15 am. There are two other persons, Pearson and Turner, whose workstations were not in use during the time of the incident, inferring that either could have accessed Turnbow’s workstation. Turnbow may have a plausible denial of not committing this act due to the fax being sent in close relation of time and that there are at least two other persons with access to his workstation at that time.

Figure 5.3 An example of plotting possible suspects in an office setting to aid in the identification and elimination of suspects.

This example applies not only to a single criminal incident, but applies also to large corporations involving many persons that committed violations in conjunction with others or individually. This concept of eliminating suspects applies across a broad spectrum of cases where multiple persons have access to the evidence devices. In the most basic form, each person must be plotted with electronic devices based on the times of alleged incidents.

Timelines

As the information increases, visual representations become more helpful in seeing how events are tied to each other, dependent upon another, and give investigative leads to more evidence. Timelines have most likely been used in legal cases since the beginning of legal cases. In the simplest description, a timeline is a chronological listing of events. The method of displaying timelines changes, whether a timeline is document listing events in order or an electronic display of colors, symbols, charts, graphs, and videos.

The use of timelines to present information in legal or corporate settings will be discussed as a presentation method in the next chapter. Investigators can use timelines to sort massive amounts of information resulting in filtering out irrelevant data, tagging important data, and gathering inferences that help reconstruct the incident. The reconstruction of the electronic crime scene is a major factor in the identification and elimination of possible suspects just as it is with a physical crime scene.

Timeline creations containing large datasets can be accomplished using specific software applications, such as log2timeline from http://log2timeline.net/ or even as an exported file listing from most any forensic application. The type of information used in a timeline is specific to the investigation at hand. Exporting every logged event, file access, Internet history, and all the myriad items of user activity to a single spreadsheet can result in millions of rows, from a single workstation. Although this massive export of data may be necessary during the investigation, most likely, the millions of rows would not be presented in legal hearings without being culled specifically to data relevant to the case.

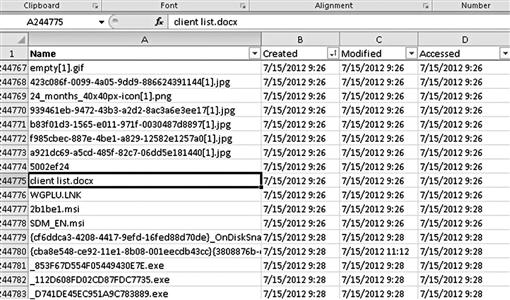

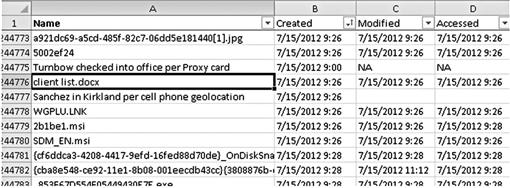

Spreadsheets efficiently sort data in a meaningful manner based on selected criteria. Whether by date and time, type of event, or by file name, spreadsheets can display relevant information quickly. Figure 5.4 shows an example of a timeline spreadsheet, sorted by date, with a sample evidence file selected. As can be seen, this is a raw data dump of information without much meaning. Although this is a simple example of one evidence file in question, a timeline spreadsheet can contain extremely detailed information gathered from a forensic analysis such as event logs, registry files, and external devices.

Figure 5.4 A basic file listing sorted by the created date and time.

Using a timeline spreadsheet to identify and eliminate possible suspects based solely on a forensic examination may not result in enough information to be useful. As any computer only shows the activity of any person that used the computer, additional circumstantial evidence needs to be added to the timeline spreadsheet.

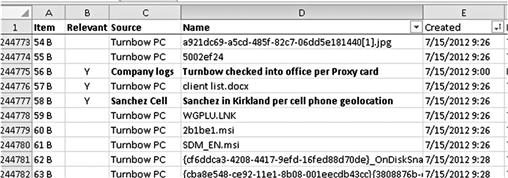

Building upon the timeline spreadsheet from Figure 5.4, other information relating to all possible suspects can be added. In this manner, a person who has been physically placed at the same location of the evidence computer at the time of use can be easily shown on the timeline spreadsheet. The additional suspect information is derived from any or all of the previously mentioned methods such as geolocation of cell phones, physical surveillance, or interviews.

Figure 5.5 shows an example of additional information derived from sources other than a forensic analysis of the evidence system. These two rows of additional information both add a possible suspect related to the evidence file and eliminate a suspect by virtue of their previously determined geolocations. Employee Turnbow is seen to be at the office (row 244776) during the time the evidence file was created while employee Sanchez is seen to be outside the office (row 2144777) at that time.

Figure 5.5 Simply adding suspect geolocation information quickly shows patterns and relationships.

Part of the task of collecting information is organizing it for a meaningful interpretation. Continually adding and deleting rows to any spreadsheet quickly adds confusion if there is not a system to keeping track of the information. Reconstruction of an incident involving more than one device in which the data is merged into a single timeline spreadsheet can make the timeline too difficult to process or completely confusing.

Some tips on maintaining order in a timeline spreadsheet include numbering rows, identifying the source of information, and marking pertinent data for ease of viewing or sorting by relevance. Figure 5.6 shows examples of each of these tips. Color coding rows are also effective in ease of viewing per relevance; however, printed spreadsheets lose some of their value if not printed in color.

Figure 5.6 Additional identifying columns help to keep order in the timeline as well as sort for specific information quickly.

Information on the timeline spreadsheet can also be rated for its veracity of authenticity. An email can be verified through several means, such as an analysis of the email if collected at various locations, such as a source computer, recipient computer, and perhaps an email server. On a reliability scale, a verified email would rate as reliable. Information obtained through an anonymous source could be rated as unknown reliability or maybe even unreliable if other information discredits the source. A scale of reliability between these ends of a reliability spectrum attached to pertinent items of information in the timeline spreadsheet allows for an analysis of the veracity of all information as it relates to each other.

Creating attractive visual displays of timelines is discussed in the next chapter, which contain only the relevant information needed for the purpose of the investigation. The timeline spreadsheets used in this manner of investigation for suspect identification will contain much more than is needed in a trial and will not convey a reconstructed incident as well as a culled dataset will.

Follow the Evidence

A gut feeling or intuition may work in the movies but not in a legal case. You need to be able to articulate your feelings and belief to be credible and your articulation must be based on factual evidence and inferences. Even your investigative actions are based on evidence, no matter how insignificant one piece of information may be; evidence must be followed to wherever it takes the investigator. So as long as you follow the evidence, you’ll find the answers to your investigation if it is at all possible.

This is especially important when there is a long list of possible suspects. I’ve never met any investigator that wanted an innocent person arrested; yet, this can inadvertently happen if an investigator forces the evidence to point to a specific person. For that reason alone, investigators should consider themselves on an evidence bus and go along for the ride to where the bus goes. That includes forensic analysis of any electronic device. Evidence doesn’t lie and doesn’t need to be shoehorned to fit a belief. Data is what it is unless proven otherwise.

Doing the best job you can, in which all possible suspects have been identified and eliminated, where the evidence shows the facts without further explanation prevents preconceived beliefs from interfering with the evidence. At worst, the investigation can show that no person except the identified suspect could have committed the alleged act. At best, you show that it was the identified suspect.

Computer user activity

Although this chapter does not go into detail on specific forensic analysis to determine user activity, it is not implied that forensic analysis of storage devices cannot be used to identify suspects. On the contrary, information recovered from evidence devices must be used to determine the how of the alleged acts and hopefully, specific information can be found that identifies suspects. Such instances include the computer user logging into email accounts or creating personal documents specific and unique to the computer user for identification.

Analyzing and looking at the activity as a whole also allows a holistic view of the investigation where patterns of activity may be seen. Comparable to a physical crime scene, an electronic crime scene may be able to show the mindset and preparation of the suspect. A haphazard use of the computer in deleting files may be that of a spontaneous act, such as after receipt of a legal hold or court order. Indications of wiped files, anonymous logins, and encryption could show a thorough manner of execution and planning by the suspect.

As the intention and theme of this book is placing the suspect behind the keyboard, all aspects of the investigation are to be used. A complete picture must be painted to ensure the suspect, and not an innocent person, is correctly identified.

Rabbit Holes

I am a believer that not every case can be solved, or at least be solved when you want it to be solved. Sometimes it may take months or years to get a break in a case. These breaks are sometimes due to a mistake made by the suspect, new evidence being discovered, or advances in technology. As a point of frustration, I’ve always preferred to solve puzzles and keep moving forward but practically, I know there is a line to be drawn on closing a case, at least temporarily.

There are also situations in which a case and investigator need to take a break. At least it is needed to have a fresh set of eyes to look over the information. As mentioned earlier, it is common to become solely focused on the details of a case and not reflect on the totality of all the information. Having persons new to your case look at your work may be effective for them to see something you overlooked or just didn’t put together. This is not a sign of weakness to ask, but instead it is a sign of being a good investigator.

Other cases may have no leads at all. Anonymous logins, proxy servers, unsecured wireless access points, no witnesses, and a one-time act with no identifying information can lead to a case that is unsolvable with the current information. This type of investigation is easy to work because there isn’t much to work with at all.

All investigations have a finite supply of resources to expend in an attempt to reach a resolution. Every forensic analysis on a hard drive also has its finite supply of resources. These resources are most always controlled by someone other than the analyst or investigator. Corporations or government entities determine the amount of resources and time to be spent on each case. These decisions come down to the financial cost to eventually solve the investigation based on the need to solve the incident balanced with the cost.

If there are no identifiable suspects and none that can be foreseen identifiable in the future, the rabbit hole needs to be closed unless circumstances change. By being creative and attempting to identify suspects using more than one method, the chances of having a successful resolution to your case will be higher than not. Some cases may have no virtual limit to expend because of the importance of the case, but practically, money, time, and personnel are not in infinite supply.

Summary

I tend to believe that the investigators and forensic analysts who want to solve puzzles involving acts committed by people must have creative minds in order to be successful. There are organizations that employ both specialized investigators and forensic analysts. Other organizations may assign an investigation to the same person that conducts the forensic analysis. Neither method may better than the other but in each case, the investigator and forensic analyst need to be aware of the totality of the investigation in order to see the events as a whole. Compartmentalization of information, where few people know the entirety of an investigation, may be good for national security incidents, but for putting a case together, everyone needs to know as much as everyone else.

Lastly, after a suspect has been identified through circumstantial evidence, as the investigator or analyst, you still should have an open mind to new evidence. A case where a suspect has been identified can be turned upside down with exculpatory evidence. Follow the evidence and make sure you identify the right suspect.

Bibliography

1. Log2timeline. <http://log2timeline.net/>.

2. United States of America v. Barry Vincent Ardolf (United States District Court, District of Maryland, 2011).