CHAPTER

3

The Power of Preparation, Invitation, Intention, and Center

Meetings of all kinds function better when the right people are in the room and they know why they have gathered and how they might contribute: this is the power of invitation and intention. Placing a visual representation of shared purpose in the center creates a focus for the group.

A leader in the human resources department, PJ, was enjoying circle process in her women’s group and wanted to bring her experience of careful listening and cohesive purpose from her monthly gathering to her meetings at work. She entered the process of preparation. “I knew something good was happening in the rounds of check-in in the women’s group that could translate to team building within the company,” she said, “if I could just figure out how to do it. And I knew that if I described what was happening in a girlfriend’s living room—half a dozen candles lit on her coffee table, Enya playing in the background, passing a conch shell from hand to hand and talking about our feelings—that I’d be up a creek and speaking Greek!” She laughed heartily imagining pandemonium. PJ’s first act of preparation is to switch the vernacular of circle to a more business-oriented frame while still honoring the experience and infrastructure of circle. This is a fairly common need for translation: people learn of circle in business and want to take it home, or they learn of circle in a personal setting and want to take it to business.

PJ calls herself a “pacing thinker.” She has worn a track in the carpeting around her desk that everyone agrees is a productive sign. “I knew the invitation had to sound businesslike and still remain somewhat holistic,” she said, pacing by. “I mean, it was possible that an appropriate but perhaps a bit surprising level of truth and heartfulness would emerge because that is what circle does. However, I didn’t want folks to feel ambushed, and I didn’t want to doom the experiment by trying to design in emotional content rather than allowing the authentic feelings people already have to emerge from the structure of circle itself.”

Whenever circle is called with invitation and intention, we need to be prepared—not necessarily for trouble but for a release of power. There are conversations eagerly waiting to occur that cannot happen until a strong interpersonal container is set out for them. In the midst of all the talking, e-mailing, and texting that goes on in our wired days, there is a corresponding silence around deeper conversations. Once people slow down, sit down, take a breath, and raise a question, these waiting topics come forth. It’s not a policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell” so much as an unconscious omission of space that allows us to ask so that we may tell.

In a harried moment around the coffee pot, the question So why did we become nurses? is likely to elicit quick repartee—“I just like blood!” (said with a laugh) or “Me? I was twenty and wanted to stay up all night and make money. Now I’m fifty, and I can’t get to sleep. Go figure.” A patient light goes on, and everyone scatters to the next task. But as we saw in Chapter 1 in the story of the Center for Nursing Leaders, the same question offered in the rim of a circle allows people to tap into the wellspring of their life purpose and to learn some poignant history about one another. So PJ is wise to tend first to preparation—of herself and of the space in which to hold such conversation.

Levels of Preparation

This is often how preparation for circle in an organization begins: one person, who becomes the initial host, reads about circle process or has an experience of circle process that is transformative and wants to apply it meaningfully somewhere else in his or her life. These initiators want to take it into the places where relationships or processes need to be more collaborative, thoughtful, and creative. Like PJ, they begin to articulate their desire for something different to themselves and imagine changed outcomes..

There are three facets to preparation: getting one’s own motivation clear, writing and extending the invitation, and literally finding time and space.

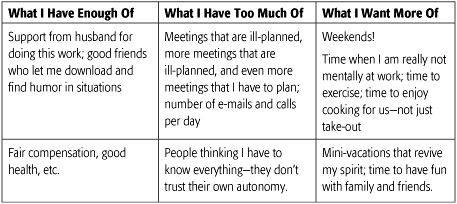

PJ began her self-explorations by making a chart with three columns (see Exhibit 3.1). Then she asked herself, What do I think circle has to do with this? She opened a folder on her computer and began an informal journal in which to jot down more questions, thoughts, and ideas that came to her in the following weeks.

While attending to her inner preparation, PJ also began to explore what her workplace had in the way of tangibles for holding a circle—chairs, tables, meeting spaces. “We’re talking major shift here,” she noted in a conversation with a friend from the women’s group. “People are used to sitting in rows, and I think they kind of like the time to check out, look like they’re listening to what’s coming down from admin, and take a little brain nap. And all our work teams sit around rectangular tables with the project leader at the head. The only place I could even find comfortable, movable chairs was in reception, and the only place I could find round tables was in the snack room. So this was going to take some thought.”

As she searched for literal space, PJ wrote a vision statement—an image of the circle experience she wished to offer and participate in. It began, “I am sitting with my team in a ring of comfortable chairs, and we are …”

These reflective activities of preparation can be refined to fit the personalities of any of us. They are useful tools in that they help us attach to a source of inner leadership that gives us courage to invite staff and colleagues to get behind a potentially huge shift in how business gets done. Leading from the rim, hosting as a peer, calling on the willingness of everyone in the room to participate fully—these are not easy requests to make. As we prepare to call the circle, we need to examine the “what I want more of” parts of our working days; we need to look for allies, other people who express a similar longing for improved relationships and uses of time. We need to think about what we will lean on for support while the group leans on us in its learning curve and early experiences.

Every morning on the way to work, PJ pulls into her favorite drive-through coffee stand and purchases a skinny tall latte. Sipping this as she moves her Toyota Matrix in and out of lanes of traffic en route to work, she attaches her iPod to the sound system and listens to music her husband has downloaded for her. “This routine calms me down and makes me ready for whatever happens when I enter the glass doors of our building. Call it a routine or ritual; all I know is, my day would not go well without it.” We all have ways we tap into intuition or guidance, a sense that we are being assisted to make wise choices of word and deed. When preparing to host a circle, taking time to amplify our connectedness to these inner resources will serve us in the circle.

It has been our experience over the years that it is exactly this inner preparedness we most need as circle work takes its turns and shifts, deepens, and lights our way. When we who host launch a question and a talking piece in the circle, we do not control what happens next. We can set expectations about time and timeliness, we have the guardian ready to help us hold the space, we sometimes have a scribe ready to record the essence—and then we trust each other and the process.

There is an inner core of preparation that serves us in this work. The more we are each able to listen for a sense of guidance, rather than pulling our responses to situations out of our habitual thinking, the more readily we prepare to receive the wisdom that lies waiting in any gathering of people. Whether calling a circle for an HR staff meeting, a men’s or women’s group, or a community gathering, taking the time to attend to all levels of personal preparation steadies us to offer the methodology and to participate with the mystery.

This is the learning curve throughout this book: leading from the edge requires that we keep calling each other back to our core purpose and that we allow a certain amount of digression, confusion, excitement, and surprise to pour through the conversation so that our creativity is enlivened by being together.

Invitation and Intention

A major aspect of calling a group into circle is the art of issuing a clear invitation. This is a “Please join me” statement that allows people to say yes, no, or maybe, to understand why they are being invited, to know who else is coming, and what commitment is requested. When composing an invitation, the host may want to consider the following questions:

![]() What is the topic to be addressed or the experience into which people are invited?

What is the topic to be addressed or the experience into which people are invited?

![]() What will be the major focus, expectation, and activity?

What will be the major focus, expectation, and activity?

![]() Who needs to be present, and why? (This personalizes the invitation to different essential participants and helps them determine if they wish to send an appropriate substitute if necessary.)

Who needs to be present, and why? (This personalizes the invitation to different essential participants and helps them determine if they wish to send an appropriate substitute if necessary.)

![]() What time commitment and potential follow-up commitment are required?

What time commitment and potential follow-up commitment are required?

![]() What does each person need to know about circle process when considering the invitation?

What does each person need to know about circle process when considering the invitation?

To issue a clear invitation, the host needs to have a clear intention. The invitation gets the right people into the room so that they can respond to and influence the intention.

PJ’s invitation for the first meeting of the year read as follows:

In her invitation, PJ clearly states her intention and invites participants to be prepared for something slightly different from the usual. Her plan is to introduce check-in and check-out, with the rest of the meeting proceeding in their usual pattern—at least for a while. At the end of the meeting, she intends to ask, “Would you be willing to add check-in and check-out to more of our meetings?” Even though she’s convinced that circle would add to the quality of her staff’s interactions, her cautious respect demonstrates one way of weaving circle into an organization over time.

Here are some other sample invitations for onetime gatherings:

A well-thought-out invitation allows people to begin to imagine their participation with some confidence about what will transpire and what is being asked of them. People come to the birthday party already thinking about their own decade birthdays. They come to Joe’s lunch with an anecdote in mind, and those who don’t wish to speak in public may write out their appreciation and slip it to him privately. Neighbors showing up at the garden meeting have been invited into an atmosphere of friendship as well as work and know they are making a long-term commitment, including a financial contribution.

All of us experience meetings and events that are not clearly called, held, or completed that work out fine. Sometimes, as in going to a friend’s house for supper or out for pizza after the ball game, we want things to be loose, undefined, and spontaneous. However, when we are asked to attend meetings that are loose, undefined, and spontaneous, frustration rises. One of the major complaints about how our time is spent, particularly in business settings, is that there are too many meetings where nothing happens. Clarity of intention and invitation will radically change the spirit of efficiency and participation in circle meetings.

Evolving Intentions for Ongoing Circles

As intention moves beyond a single event, the complexity of what’s being addressed may quickly change or expand and require additional thought from the caller of the circle and from the group.

Here is a private example of shifting intention. A few years ago, Christina was seeking a small monthly circle of local friends willing to join in a conversation deeper than after-dinner gatherings. She sent out an invitation that articulated her idea for the general framework. Three people responded, “Yes—let’s try it together.” As it turned out, all three are women who keep journals. After a couple of months, it became clear that the deepest need for each of them was to enjoy a few hours of quiet writing time, followed by reading their journal entries and a check-in. Almost without noticing, they shifted their intention from topical conversation to writing reflection. At the end of each year, they revisit the structure and choose whether or not to enter another cycle.

While this circle is ongoing, someday it is likely to come to a completion. The women honor the cyclical nature of circles by asking each other from time to time: Is this still nourishing us? Do any of our patterns need to change? Is there anything more or less we want of each other? These are not the kinds of questions we ask very often in business—and what a shift would occur if we did.

Here’s an organizational example. Our colleague Bonnie Marsh provided a powerful template for bringing circle to her organization. At the time we first worked with Bonnie in the mid-1990s, she was corporate senior vice-president for strategic development at Fairview Health Services in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Bonnie had read a newspaper article about the first edition of Christina’s book, Calling the Circle. She purchased a copy, was excited by the ideas, and approached her CEO, Rick Norling. “If I am going to do this huge work of bringing together departments that have not worked together before, I need to do it differently,” she said to Rick. She handed him a copy of the book. “This is what I’d like to try. What do you think?”

A few days later, Rick strolled down the hall, put the book back on her desk, and said, “It could be a little soft as a management process. On the other hand, if it works, it could be exactly what you need.” Bonnie promptly gave copies of the book to each of her eighteen managers, asked them to read it, and invited them to try staff meetings in circle. Most of the managers under her jurisdiction—organizational development, human resources, and strategic planning—had never met together before. People agreed to try the experiment, and we traveled out to offer three days of training. They didn’t know it, but the team was our first big corporate client. Our time with them was truly a mutual learning experience.

Bonnie’s attention to the importance of getting permission from her superior and then getting acceptance from her reporting colleagues set a tone of inclusivity and ownership that ultimately led to great success. She respected the triangle structure in place and used it as a foundation on which to introduce circle structure. In Fairview hierarchy, Bonnie was the boss: in the circle, she was a colleague holding her corporate rank in the background. Like so many creative leaders, she genuinely believed in gathering the wisdom of the whole, and she had to do it without pretending that the other structures didn’t influence the circle.

When the circle comes into organizational settings, the triangle is always present. Circle process morphs back and forth between moments of freewheeling collegiality and recognition of authority. Bonnie deliberately avoided hosting as much as possible because she didn’t want her status in the hierarchy to weigh heavily in the group. And yet there were times when the circle counted on her to carry issues and ideas to the CEO.

As the months progressed, the circle established itself as a “no guilt” zone where these incredibly busy department leaders could use the safety of their agreements and confidentiality to share their challenges and support one another. As Bonnie had hoped, the old mode of communicating only within departmental silos changed significantly.

Over the next four years, we made annual visits to consult with the management circle. “I believed thoroughly that we needed to bring more heart and spirit into our work, and I knew that it was absent in most of the forums I was in,” explained Bonnie. “Circle provided a phenomenal shift for us.” By the end of the second year, these managers talked about how to have maximum impact on their eighteen thousand–employee system. They even considered dropping all department titles and redesigning themselves into a single “strategic development department.”

“For me, that was clearly the biggest marker that something different was happening,” said Bonnie. “Another important moment was the day one of our members came to the circle asking for help in how to respond to a corporate memo that told her there was nothing to be done about employees’ complaints in a unit that desperately needed resources and attention. She wanted the circle’s assistance to formulate a position statement that would communicate to top management that this was an unacceptable response that was sure to create more problems. It was a delicate and complex situation where the manager felt responsible to the unit, which had worked to voice a coherent complaint and request help, and she understood the priorities and constraints at the upper-management level. The circle helped her to craft clear language. She took her intervention to corporate and worked toward a better resolution. I don’t think corporate ever knew she stood with the circle at her back the way she did and that we were watching her progress.”

In an ongoing group like Bonnie’s managerial team, intention needs to be periodically revisited. She set an intention for meeting in a more inclusive, circular fashion, and both her boss and her team responded positively to the invitation as issued. Once they had experienced the impact of circle process for several months and claimed it as their own, they needed to revisit intention so that the words continued to serve their needs and reflect their evolution.

Over the next few years, as the group matured and shifted, added new members, and changed responsibilities, it required a number of conversations about the role and intention of the circle in the expanding corporation. They held on to their agreements and Fairview’s core values; they held on to their time together for four years. Bonnie and others moved to positions outside Fairview, and slowly the circle dissipated as the remaining people ended up reporting to different vice-presidents and others were laid off. However, that circle seeded circles in other organizations that are evolutions from this pioneering experience.

Personal Intention in Group Process

Groups always consist of some people who are primarily focused on tangible accomplishment and want reflection afterward and other people who enjoy reflecting on the quality of process and relationship before diving into action. For those focused on tangible accomplishment, talking about group process is often frustrating because they don’t perceive it as part of the “doing.” For those who ground their work through understanding process, overlooking circle’s potential for deepening relationship seems a misuse of the form: they want to “be” together before “doing” together. Circle requires members to constantly balance individual style and group intent. Remember, there is something each person wants to have happen; there is something the group wants to create. These two energies need to coexist and cooperate.

In Christina’s personal circle, the original intention was to create a social container to explore specific questions. In Bonnie’s managerial circle, the intention was to increase communication between different departments. Both of these intentions are quite broad compared to an intention among neighbors to start a shared vegetable garden. Whether circle intention is broad or specific, individuals arrive with their own motivations, desires, and agenda. The ability of people to hold their personal intentions within the collective intention is greatly helped by keeping these issues part of the ongoing conversation.

In a cooperative environment, personal intention (what I hope to contribute and gain) and group intention (what we can accomplish by being together) are held in balance. However, since we live in an atmosphere dominated by competition, people often come to circle carrying an internalized competitive edge, even if they don’t mean to. We often speak of circle as a process of remembering how to behave differently—switching from acculturated competition to voluntary cooperation. One way to help this shift occur is to acknowledge that everyone has a personal intention and to name it as part of group process. Perhaps everyone completes statements such as these:

![]() I joined this group because …

I joined this group because …

![]() I most want to contribute …

I most want to contribute …

![]() I most need to receive …

I most need to receive …

![]() I’d like to look back on this experience and see that I …

I’d like to look back on this experience and see that I …

Each person then reads his or her statement to the group in a round of talking piece council followed by open conversation. Sometimes we invite people to write their statements on large sheets of paper and post them along one wall of a room or spread them out in the space between the rim and the center so that we can work with the patterns of commonality and diversity that show up.

Another possibility is to open a circle using the check-in question: What intention do you offer circle today? Individual intentions are then all clearly placed in the center—sometimes with people literally placing an object symbolic of their personal intention in the center. A rich conversation about how to combine them into a cohesive working intention can then emerge.

Center

Two things are immediately noticeable when participants walk into the room where circle is being held. First, the chairs are in a true circular shape, or as close to that shape as furniture allows, and second, the head of the table or front of the room has been replaced by a center.

The conscious placement and use of the center is one of the primary contributions PeerSpirit Circle Process offers modern conversational methodologies. Because circle was first held around a common fire, center is remembered as a place of warmth and light. Just as fire requires tending, the center of the circle also requires tending. Even when no fire is present, people will talk to a center point and understand that the energy of shared intention resides in the carefully chosen symbolic objects placed in the middle of the circle.

The Fairview circle conducted its twice-a-month business meetings sitting in a circle of chairs with a low coffee table in the center. At the first training, we inscribed four placards for the group,, that stated the four corporate core values: “Service,” “Integrity,” “Dignity,” “Compassion.” The placards were then placed on the coffee table along with a small vase of flowers. The group adapted and maintained this center and counted on the visual presence of the four values. Periodically, individuals also placed objects in the center in response to a check-in question.

Objects placed in the center allow people to visualize and remember their reason for gathering. Centers are as variable as circles themselves, for they reflect the highest intention for the group’s gathering. At a school board meeting, the center might be a bowl of apples. In a gathering of nurses, a replica of the Florence Nightingale lamp might reside in the center. A group of wilderness guides will likely be gathered around a real campfire. A group of financial planners might place client portfolios and ethics statements in the center with an old-fashioned piggy bank.

Perhaps the most elaborate center we’ve experienced was in the middle of a gymnasium floor with forty-five Wheaton Franciscan sisters seated in padded chairs around it. The gymnasium was the only place in their motherhouse large enough to host a circle of so many women. The yellow pine floorboards with the black markings for basketball games seemed an unusual place to engage in a dialogue with religious women about the future of their province. Yet the highly visionary leadership team of Provincial Marge Zulaski and Gabriele Uhlein, Patricia Norton, and Alice Drewek, understood the introduction of circle process as the paradigm shift they sought for their community and the legacy of their leadership.

Sister Gabriele volunteered to design a strong visual center. The transformation of the gymnasium was amazing: rice paper screens encircled the backs of the chairs, creating an effect that the whole circle was being held and protected. The center itself was about twelve feet in diameter with candles, flowers, and cloths coordinated with the colors of the liturgical season (see Figure 3.1).

During the opening of each “wisdom circle” (two- or three-day gatherings held quarterly over an eighteen-month period), the sisters spoke into a handheld microphone that served as their talking piece and each placed a personal object at the edge of this center—thus adding their individual intentions to their work together. Day after day, the women spoke into the reflected beauty of their lineage to voice thoughts, feelings, and opinions. During evening sessions, when the mood was set more for story and reflection, the center shimmered with candlelight to evoke heartfelt sharing.

Later one sister commented, “The center prepared the space, and bringing an object to the center prepared us. When I looked around to choose an object for the center, it required thinking about how I was coming to the meeting. Our center enabled a clearer quality of arrival in us.”

FIGURE 3.1

Intention and center are the most basic components of circle. Intention holds the rim and sets the parameter. Center holds the heart and the mindfulness of why we’re gathered. If a circle stops feeling like a circle and slips into versions of triangle in the round, reviewing intention—both personal and collective—is a democratic way of reestablishing focus. And reactivating the center so that it has a pleasing aesthetic and meaning can provide a calming attachment to the archetype that supports us in these modern experiences of our ancient social patterning.

PJ is right to be thinking things through. The initial call to circle she made for the January meeting has immediate and long-range potential to change the ways she works with her team and how the team works with her. She needs to be ready, and so does the team. The power of preparation, invitation, intention, and center releases the ability of circle process to accommodate significant shift. Though the circle no longer meets at Fairview, this pioneering group of early adopters set the template for much of our later work. And many of these nurse and health care leaders have moved into other corporations, consulting practices, and associations where they carry their circle experience forward.

The Wheaton Franciscans have elected a new provincial leadership team, and their story is continued in Chapter 5.