CHAPTER

2

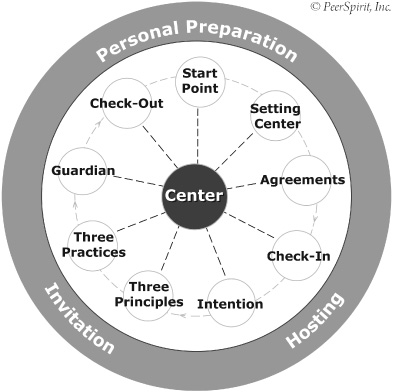

The Components of Circle

Every conversation has an infrastructure, an understood pattern of participation. The conversational structure of PeerSpirit Circle Process is outlined here through a map known as the Components of Circle. The entire process is first presented here as a reference within the longer narrative, explicated in Chapters 3 through 6, and placed in the context of circle as a social art form in the remaining chapters of the book.

This chapter serves as the operator’s manual to actual circle practice. The information here is like that little booklet in the box that says “Some assembly required” in seven languages. To assemble the circle you will need the following skills: interest in other people, a good question, and a supply of trust, tenacity, and time. Once assembled, you will have the following tools: a ring of chairs, a center, a bell, and a talking piece. With these skills and tools you’ll be ready to engage your family, friends, and colleagues in an amazing collective experience. Step one in the assembly of circle: understanding that all forms of conversation are based on social infrastructure.

Social infrastructure is the pattern of exchange that allows us to interact with a sense of confidence that we are being appropriate to the moment. (“Hi, how are you?” is a social infrastructure, and so is the nearly automatic response, “Fine.” We don’t even need to think about it: one sentence signals the next.) There is social infrastructure in a lecture (unless you’re the speaker, be quiet and listen; taking notes is a sign of respect), in a debate (timing is everything, get your points in, look bold, interrupt if possible)—and in circle.

In circle, we interact in a slightly more formal pattern than casual conversation. Circle’s potential for depth and insight is ever present, and it requires that we pay increased attention. The actual content of what we say may be the same, but the patterns of engagement—who speaks when and how we listen, how we interact, and what is expected of us after the circle conversation is finished—are influenced greatly by circle structure.

A Structure for Conversation

Everything has structure: a shape or form that defines what it is. The human body, for example, is defined by the internal structure of our bones. The flesh of our physical bodies comes in nearly seven billion variations of size, shape, age, skin tone, and hair. Yet from as far off as we can see someone coming, we recognize and name that moving shape “human” based on how our skeletons hold us up and allow us to move.

Even as a two-year-old walking into a day care center in Los Angeles, Ann’s grandson was not confused by an array of toddlers of all colors. “Baby, baby, baby …,” he would call out, practicing a favorite word. His friends all looked up: an array of little Asian, Hispanic, African American, and Caucasian faces, each different in appearance but similar in structure. We are recognizable by our bones.

We also know the circle by its “bones”—a definable structure that fleshes out in different articulations of the same form. As PeerSpirit moved into the twenty-first century, we were increasingly called on to make circle process accessible to more diverse and international audiences. Aware of our white, middle-class, American backgrounds, we went looking for a way to talk about circle that would translate cross-culturally. We began to think of the structural elements of circle as having a skeletal quality, a basic infrastructure that could flesh out with great diversity and still retain its integral form. As long as those “bones” were in place, people would recognize circle as the underlying pattern. This articulation of the conversational infrastructure as “bones of circle” first occurred to us in December 2000, when we were part of a facilitation team offering circle process to an international group of young and middle-aged community organizers.

We met at Hazelwood House, a genteel Victorian retreat center in Devonshire, England, as part of a teaching team in a movement then called From the Four Directions (F4D). F4D had been founded by Margaret J. Wheatley to introduce living systems theory and circle process in support of cross-cultural community leadership development. Having arrived from countries as different as Zimbabwe and Croatia, thirty people squeezed into a circle of chairs in a rectangular room. The conversation occurred in English, though for many this was a second or third language. In preparing for this event, the two questions PeerSpirit had been considering were How could we most readily present the universality of circle? and How could we talk about the invisible elements of conversational structure in such a way that everyone could identify how circle was already present in the cultures they came from?

By the time everyone gathered, England was in the midst of a hundred days of winter rain. The house was drafty, and many participants had arrived from warmer climates with inadequate clothes. To warm up, the young people put on music and the whole group rose to dance—arms and legs akimbo until we found a common rhythm. In that rhythm, suddenly it was obvious: we saw social interaction as a kind of dance with shape and form that defines what it is. We saw interaction as a skeletal system, in which the understood rules of engagement shape our meetings and allow us to move in certain ways and restrain us from moving in other ways.

In that room in Devon, we handed out the Components of Circle illustration (see Figure 2.1) and referred to it as the “bones of circle process.” The metaphor translated well, and we have introduced it this way ever since.

The Components of Circle in the PeerSpirit model are also skeletonlike in that they connect to each other, move each other, and work best when all are active. This chapter presents the entire skeleton so that you can think about the model as a whole and can talk it through with others.

Circle can be introduced using a few pieces of structure or using the entire structure. It can work without activating all components at once—much as we shake hands without using the whole body. Yet our handshake conveys the structural strength of the whole body. Both parties know they can engage more deeply as needed—as when a handshake turns into a hug or a casual greeting turns into a heartfelt exchange. When circle interaction is gentle, we sit relaxed. When interaction is strenuous, we lean in to avail ourselves of the strength of the full structure. For purposes of simplicity, we are going to assume that you are calling the circle. You are getting ready to invite circle practice into a new setting or into an ongoing group that you hope will be willing to adopt circle as the process for its meetings or conversational time.

FIGURE 2.1

The Components of Circle

On the Rim

Circle structure begins at the rim with three components: personal preparation, invitation, and hosting. There is prep work to do in calling a circle. It starts with personal readiness, then invites others into the process, and finally asks you to take the initial leadership role as the circle’s first host.

All processes have their own jargon. It is our intent to provide a common vocabulary of understanding about what goes on in circle and then to demonstrate how circle allows people to adapt the process to their own environments and purposes so that they might integrate circle jargon in meaningful ways.

Personal Preparation

Circle requires an intensified sense of showing up. While this intensified and intentional presence fosters rewarding conversations, it’s not casual: every person’s engagement or lack of engagement is noticeable. There is literally no space to hide out, to multitask, text-message, read unrelated materials, or nap. We will be leading from every chair, sitting as peers, taking risks that call on the capacities of participation and leadership from everyone in the room. Everyone is accountable to everyone else and to the purpose of the meeting.

This is often not the kind of space we are entering as people rush down hallways finishing phone calls and tossing drive-by comments to those they pass: “Joe, Tuesday, lunch. We’ll talk about that staffing issue.” One of the gifts of circle is to slow us down and provide a place to stop and listen, to take a breath and consider the fullness of what we want to say to each other. Personal preparation is, essentially, the practice of shifting from whizzing to attending. When we turn off the phones, the beepers, whatever little pieces of equipment keep us attached to the multitasking world, it is an invitation to take a few breaths, look around, get nourished and comfortable, focus on the people actually in the room, and take a place so that the meeting can begin.

If you are acting as host, there is additional preparation you need to have done. The host prepares the ambiance of the meeting space and has done whatever prep work may be needed. He or she has carefully considered who needs to be present and invited them. The host comes prepared to open the meeting with a start-point and check-in and has made sure people have what they need to participate.

When a friend of ours decided to host her book group in circle, she reminded everyone of the time and place and put some thought into refreshments and ambience. She finished reading the book early so that she could come up with several good questions. On the day of the meeting, she took time for a walk through the park after work and arrived ten minutes early at the library community room to make sure the space was inviting, warm, and ready. She had taken care with her own sense of groundedness and readiness and approached the evening with relaxed preparedness.

Invitation

People appreciate clarity. A verbal or written invitation addresses the questions For what reasons are we coming together? Who will be or needs to be present? What kinds of contributions are expected of me? (And if circle process is being introduced for the first time, Why are we using this approach, and what does it look like?)

Invitation is understood in both work and informal settings. When Ann’s parents turned seventy-five, nearly the entire family gathered for a shared summer vacation. The invitation announced that Saturday evening would include a “talking piece council” to honor these parents and grandparents and invited everyone to think of a favorite story that illustrated the values these two elders brought to the family. The invitation prepared family members for participating in something slightly different than the usual barbecue.

In a work setting, a new board chair decided to ask the board to try using circle process for three meetings to see how it might affect their communication and decision making. He e-mailed board members this invitation:

At our next meeting, we will be addressing the need to update our mission and vision statements. I would like us to try an approach known as “circle process.” It will follow the structure outlined in the attached “Basic Circle Guidelines.” Please read this document before the meeting and come with an open mind. Please also bring an item that you feel represents the contribution our organization is making to its constituency. These objects will help us focus our discussion. In both the family and the board situation, hosting is happening: someone has taken the leadership role to say, “Please come,” “Let’s do things this way,” “Let’s talk about this.”

Hosting

Hosting is part of our ingrained sense of social order. A host prepares and holds the space for a conversation to occur and then participates in the conversation as it occurs. At a dinner party, the host prepares the menu, sets the table, creates the ambience, puts thought into people’s comfort—and joins in when the party begins. Things usually start off as expected, surprises happen, the event takes on a life of its own, and most of the time it all works out. Someone says, “Oh, let’s do this again—next time I’ll host.”

In an ongoing group, it is helpful if different people host over time so that leadership rotates and everyone has the opportunity to practice. In a management leadership circle, one manager at a time hosts the conversations. The next month, the hosting shifts. In this case, hosting involves reserving a comfortable and private room, reminding the group of agreed topics of conversation, and taking leadership at the end of the gathering to ensure that topics are set for the next meeting—for which a new host steps forward.

The host can be responsible for the invitation and for introducing the components of circle—especially at the first few meetings as others learn circle process. The role of a host is more integrated than that of a facilitator. Facilitation is usually conducted by someone who stays outside the process, who attempts to take an overview, may introduce the process and the agenda and perhaps even the outcome, and devises the way the group will get to its goal. A host sits within the process. Like everyone in the circle, the host notes what topics arise, invites participation, and calls the group to shared accountability for how it will reach its goal.

Internal Components of Circle Structure

The first thing to do in calling a meeting into circle process is to literally form a circle shape. Perfect roundness is not required. Circle shape can accommodate living room furniture, square walls, or, when necessary, a boardroom or dining room table. In a recent meeting in a very oblong room dominated by a rectangular table that didn’t seat the entire staff, we invited everyone who was at the table to push back their chairs and everyone who was stuck in the corners to roll their chairs forward and join the rim. This made a shape more like a big egg than a circle, but it accomplished what was needed: the people in the room became one group. We then enjoyed a meaningful round of conversation. The purpose of sitting in a circle is to allow people to notice all who are present, to see who is talking, to hear one another better, and to interact fully with the other participants.

However, walking in and finding the chairs arranged in a circle can be a bit discomfiting at first. Circle signals a much higher degree of participation and a greater sense of physical exposure. Ideally, if your invitation was effectively crafted and issued, people will come to this experience assured that their time and energy will be well used and their participation valued.

It’s OK to be creative about the question of gathering around a table versus using a circle of chairs with no table or a low coffee table at the center. We have helped hosts work the issue out in a number of ways. One committee we’ve watched over the years developed a pattern of opening the meeting by sitting in a circle of comfortable chairs around a small coffee table that held symbols of the meeting’s purpose. Because people appreciate having a table for writing and spreading out documents, they then switch to a nearby table for an agenda-based circle. At the end of the meeting, the group returns to the circle of chairs for closure. In another group, where there are often forty to fifty participants, everyone gathers in a large circle of chairs with an elaborate center that helps fill the space, and all conversations of the whole are held there. From this space, the participants periodically adjourn to clusters of small circles in an adjoining room. As people grow accustomed to the use of circle process, they often find that gathering around a table inhibits their sense of engaged interaction. They want to sit fully in the simplicity of a circle shape—gathered around a center with a full-bodied presence.

Center

The conscious placement and use of the center is one of the primary contributions of circle to conversational methodologies. If we think of the circle as a body, the center is the heart. If we think of the circle as a wheel, the center is the hub. If we think of the circle as a campfire, the center is the fire itself.

Because circle was originally held around a fire, the center always produced warmth and light. Fire requires tending: adding logs to refresh the flames, cooking food in hanging pots or wrapped and placed on the coals, banking embers for the night. The center of the circle also requires tending. We put something in the middle that is meaningful—a symbolic representation of a group’s intention, purpose, or goal—and these objects allow people to visualize their reason for gathering.

In business, this might be a display of placards of company values or project goals; in education, it might be student photos and the school logo; in an informal group, the center might consist of a candle, some flowers, or a few natural objects. One simple object can make an unobtrusive and yet powerful center. Think of a circle called during a crisis and in the center of the carpet is a smooth gray rock the size of a brick into which the word IMAGINE has been laser-etched. Think of a circle gathered around a table with a small spiral of pens and Post-it notes in the middle and the invitation to take note of each other’s essential contributions. People tend to rest their gaze on whatever is placed in the center, to use it as a focal point.

A tangible center creates an intangible third point between people, a sort of common ground. In customary dialogue, person A speaks, person B listens and responds, person A signals that he or she is listening, and the words go back and forth like a verbal game of table tennis. In circle, person A speaks and verbally places his or her comment in the common ground of the center, then person B speaks and places his or her response in the common ground. The sense of placing a comment or story in the center can be done by gesture, body language, voice tone, or statement (“I put this story to the center”). The center provides a neutral space where diversity of thought, stories of sorrow and outrage and heartfulness, can be held and considered by all participants.

What most often causes us to shut down and stop listening to each other is the sense that we are being barraged by another person’s intensity: the person won’t stop talking until we either agree or disagree. However, in circle, people can agree and disagree and keep on listening as long as each person’s intensity is laid down in the center instead of against another’s chest. Use of the center becomes like working together on a jigsaw puzzle, piecing our knowledge, wisdom, and passion into a coherent sense of what is going on and how we can respond. As people talk, ideas link up and synergy builds.

Start-Point

A meeting in circle has a beginning, middle, and end. We shift from social space into circle space, do the process, and then shift back out into social space. The host or other volunteer offers a simple ritual to signal these shifts. It may be ringing a chime that beckons silence, lighting a candle or setting out the center objects, or reading a quote or short inspirational reading. Any of these actions elicits the reflective attention of those who are gathering. The circle is beginning: the infrastructure is now called into play.

A friend of ours, a community college president, always begins her staff and faculty meetings, and even college assemblies, by reading a poem. “Poetry, recited aloud in settings where that is no longer common,” she says, “calls people to a kind of listening I find useful. The cadence of poetry offers a sense of calm, prepares people to interact differently, and often inspires a metaphor that shows up later in the day.”

People use start-points whenever they want to initiate a contained conversation. In Alcoholics Anonymous, participants recite the Twelve Steps. At school, students recite the Pledge of Allegiance or sing a school song. In organizational settings, people may read their intention statements and group agreements.

Circle Agreements

Like all social processes, the success of circle rests on the ability of participants to understand, contribute to, and abide by rules of respectful engagement. Agreements provide an interpersonal safety net for participating in the conversations that are about to occur. In a circle, where people rotate leadership and share responsibility, agreements remain constant while leadership changes and task or intention evolves. Agreements are the circle’s self-governance, and they create a way for each member to hold both self and others accountable for the quality of interaction.

In an ongoing circle, we recommend that people take time to generate agreements specifically suited to their purpose and articulated in their own vernacular. Since the circle has gathered around an intention, and in response to an invitation, the host may ask, “What agreements do we need to have in place to be able to fulfill our intent?”

When hosting a new circle or in a brief or onetime meeting, we offer the following generic agreements:

![]() Personal material shared in the circle is confidential. It is worth spending time considering the applicable parameters of confidentiality in order to ensure that all participants share a definition of what is meant and expected of them regarding this issue.

Personal material shared in the circle is confidential. It is worth spending time considering the applicable parameters of confidentiality in order to ensure that all participants share a definition of what is meant and expected of them regarding this issue.

![]() We listen to each other with curiosity and compassion, withholding judgment. Curiosity allows people to listen and speak without having to be in total agreement: curiosity invites discernment rather than judgment.

We listen to each other with curiosity and compassion, withholding judgment. Curiosity allows people to listen and speak without having to be in total agreement: curiosity invites discernment rather than judgment.

![]() We ask for what we need and offer what we can. This agreement is a form of self-correction in direction. Generally, if a request fits the task and orientation of the group, someone in the circle will volunteer to help carry it forward. If a request doesn’t fit task and orientation, no one is likely to volunteer.

We ask for what we need and offer what we can. This agreement is a form of self-correction in direction. Generally, if a request fits the task and orientation of the group, someone in the circle will volunteer to help carry it forward. If a request doesn’t fit task and orientation, no one is likely to volunteer.

![]() From time to time we pause to regather our thoughts or focus. To create these pauses, one member of the circle volunteers to serve as the guardian, who employs a bell or other nonverbal aural signal to introduce a moment of silence into whatever is taking place.

From time to time we pause to regather our thoughts or focus. To create these pauses, one member of the circle volunteers to serve as the guardian, who employs a bell or other nonverbal aural signal to introduce a moment of silence into whatever is taking place.

Sometimes negotiating agreements is a fairly quick and easy process; sometimes it is slow and complex. Negotiating agreements is a strong indicator of the level of trust and confidence, or of tension and concern, that already exists in the social field. A group will learn a lot about itself in this process, and sometimes much confusion will be cleared away. It’s not always comfortable. A wise young Englishwoman once announced in the middle of our negotiations, “People, these are not frivolous phrases—we’re making a life raft here! Our agreements are what carries us through stormy seas.” In response to her charge, the group made strong and thoughtful agreements—and she was right: we needed them.

Check-In

As circle starts, the first time everyone has an opportunity to speak is called check-in—a chance for all participants to introduce themselves, respond to the invitation, or share stories about what brings them to the circle. Check-in is often framed as a specific question or direction offered by the host:

“Please share a brief story of what drew you to participate in this circle.”

“What excites you about being here, and what concerns do you have?”

“What has happened in the past few days that inspires you about this organization?”

The use of the talking piece greatly helps the check-in process. A talking piece is any object passed from hand to hand that signals who has the right to speak. When a person is holding the talking piece, he or she is talking and everyone else is listening without interruption or commentary. (The use of a talking piece controls the impulse to pick up on what a person is saying, to interrupt with jokes or commentary, or to ask diverting questions. It is a powerful experience to listen to one another in this way. The talking piece has served this purpose in circle since ancient times.) Circle protocol always respects the choice of someone who wishes to pass along the talking piece without speaking and remain in listening mode. At the conclusion of the round, the host usually asks if those who passed up the first opportunity are now ready to speak and offers them a chance to talk without any implication that speaking is required.

The talking piece is a great equalizer among those who differ in age, ethnicity, gender, or status. The piece assures that everyone at the rim has a voice. In modern settings, where clock time is always a factor, it is helpful to suggest a time frame for a round of the talking piece. Do “time math” for the group: “We are X number of people. If we each speak for two minutes, that means …” In the first round of a new circle, check-in may take longer than at later meetings. Typically, people become quite skilled at checking in with both meaning and brevity.

In smaller circles or among long-standing groups, the talking piece is sometimes placed in the center and people reach for it when they are ready to contribute. Although circle process does not require constant use of a talking piece, its use is suggested for check-in, for check-out (to be discussed shortly), and whenever it would be helpful for people to slow down and hear everyone’s contribution.

Intention

Rotating around the Components of Circle diagram, we come to intention. Intention is the understood agreement of why people are present, what they intend to have happen, and what they commit to doing and experiencing together. The invitation articulates the host’s intention. Sometimes intention is concrete: we are gathered to vote on finalizing this year’s budget. Sometimes intention combines the concrete and visionary: we are gathered to vote on a budget that will enable us to focus on meeting the changing environmental needs of our community. Sometimes intention is ideological: we’re here to have a conversation about how to improve community relations.

Defining intention is a process of self-examination for both the individual and for the group as a whole. Intention gets us in the room with each other, usually glad that someone took the initiative to host the conversation, and starts us toward action—and then, once we all contribute, intention evolves. For example, if the intention for a meeting is to generate ideas to improve customer service, each person arrives with a slightly different personal intent. One person’s intention may be influenced by the fact that she is in charge of customer service and needs to present herself as being “on top of things.” Another person’s intention may be influenced by the fact that he is tired of customer service “getting all the attention” and wants to move through the agenda item quickly and into his area of expertise. Ultimately, the group intention is shaped by all these individual tensions and, hopefully, draws forth a synergy of creativity that becomes a collective vision.

Intention requires a conscious balancing between personal and collective needs. There is something each person wants to have happen: there is something the group wants to create. When these two energies emerge and coexist, the circle really steps into a sense of itself.

It is as important to the long-term success of a circle to spend as much time honing the intention as it is spending time crafting the agreements. Intentions can be made clearer by including a time frame. For example, in gathering to save trees and create a park, the group may agree to meet for six months and work toward that goal and then revisit their progress. Softer, more loosely defined intentions also benefit from a time frame: “Let’s have a monthly breakfast meeting to talk about neighborliness and then check if we are being personally nourished by the conversation and want to continue it.” The clearer the intent of the people in circle, the more focused the dynamic of the circle will be. Reworking intention can save a circle that’s floundering or help a group understand how to set itself back on track.

Three Principles of Circle

Circle process functions under three principles of participation: rotating leadership, sharing responsibility, and relying on wholeness.

Rotating leadership means that every person helps the circle function by assuming increments of leadership. This is evidenced in the roles of host and guardian (and scribe, when that function is needed), and every person is invited to interact in circle with a sense of self-determination, volunteerism, and tending to common needs. “I could do that, let me take that on.” Rotating leadership trusts that the resources to accomplish the circle’s purpose exist within the group. If no one is interested, that lack of interest becomes the next topic of conversation, an exploration without blame or judgment.

Sharing responsibility means that every person watches for what needs doing or saying next and makes a contribution. Sharing responsibility breaks old patterns of dominance and passivity and calls people to safeguard the quality of their experience, to jointly manage the allocation of time, and to notice how decisions arise out of group synergy. “Guardian, could you ring the bell? We’ve veered off topic here, and I want us either to get back or to make a clear decision to digress.”

Reliance on wholeness means that through the act of making individual contributions, people in circle generate a social field of synergistic magnitude. Reliance on wholeness reminds people that the circle consists of all who are present and the presence of the circle itself. Wholeness is an animation of circle process beyond methodology; it acknowledges the archetypal energy of circle lineage. Things happen that we do not expect, and we discover in ourselves the capacity to respond brilliantly.

Many of the stories throughout this book illustrate the principle of reliance on wholeness; these are the memorable moments that people ponder, are moved by, and look back on as turning points. Whatever skills and talents we bring to a circle meeting, whatever hesitancy and doubt accompany us into an issue we fear is irresolvable, this principle invites us to remain present and attentive to our interactions on the rim and to attach our energies to the center, like spokes on a bicycle wheel, so that the synergism of wholeness may hold us and spin us.

Three Practices of Council

The practices of council invite circle participants to speak, listen, and act from within the infrastructure in place.

Attentive listening is the practice of focusing clearly on what is being said by someone else. In circle, listening is a contribution we offer one another. There is too little actual listening in the world; too often we are waiting for our turn to insert our own thoughts and stories. Listening through the center of the circle allows us to receive people’s thoughts, feelings, and stories and stay separate from them, stay curious, look for the essence, seek a place to connect even when there is surface disagreement. Attentive listening is a kind of spiritual practice that shifts us out of reactivity and into deep inquiry.

Intentional speaking is the practice of contributing stories and information that have heart and meaning or relevance to the situation. It comes from the patience of waiting for the moment when we each really understand what to contribute and when receptivity is alive in the group. Intentional speaking does not mean agreement; it means noticing when the piece of the truth that is ours to say may be received and then to say it, avoiding blame and judgment—to speak in neutral language. It means that attentive listening is in place and that each person is able to make a contribution while still tending to the well-being of the group.

Attending to the well-being of the group is the practice of considering the impact of our words and actions before, during, and after we speak. It is important to take time before speaking to inquire of ourselves what it is we want to contribute. Typical questions to the self might include the following:

![]() What is my motivation or hope for sharing this?

What is my motivation or hope for sharing this?

![]() What is my body telling me about tension or excitement?

What is my body telling me about tension or excitement?

![]() How do I offer my contribution in a way that will benefit what we’re doing?

How do I offer my contribution in a way that will benefit what we’re doing?

![]() How do I need to consider what I say, before I say it, and still speak my “truth?”

How do I need to consider what I say, before I say it, and still speak my “truth?”

These practices are profound gifts of circle process: that we can speak the fullness of what we have to say and listen to the fullness of what others have to say and do so in ways that sustain relationship.

Guardian

While all participants hold the infrastructure of circle, the role of mindful watching falls to the guardian. We adapted this role to circle process after attending a lecture in the early 1990s by the gentle Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh. He sat on a simple meditation cushion on a raised dais so that the thousand people in the hall of the hotel conference center could listen attentively as he spoke softly into a microphone. Several times in the middle of his speech, his traveling companion rang a small, resonant bell from somewhere in the middle of the audience. Thich Nhat Hanh ceased speaking and entered a thoughtful silence—and so did the thousand listeners. After a while, Thich Nhat Hanh would announce quietly, “The bell calls me back to myself,” and resume speaking while we resumed attentive listening.

The guardian observes both practical and spiritual needs and tries to be extraordinarily aware of how group process is functioning. To employ guardianship, the circle needs to supply itself with a small brass bell, chime, or other object that makes a pleasant sound loud enough to be heard during conversation (a rattle, rain stick, or small drum might be appropriate, depending on the setting). Usually rotating on a meeting-by-meeting basis, one person volunteers to serve in the guardian role. The guardian has the group’s permission to intercede in group process for the purpose of calling the circle back to center, to slow down conversation that has speeded up, to focus on the group’s intention or task, or to return to respectful practices as outlined in the agreements. The guardian also works with the host to stick to the time frame of the meeting or agenda and to call for breaks when necessary.

The use of a chime or bell as part of group process is becoming increasingly common. A pair of Tibetan cymbals, called tingsha, will resonate in human ears for fifteen seconds—time to take an elongated breath. Tingsha has its own Wikipedia entry, along with Tibetan singing bowls. Tone bars or bar chimes, consisting of a horizontal silver tube suspended on a wood base, are available at mainstream music stores.

When the guardian rings the bell, conversation and interaction stop. Everyone takes a breath and waits for the guardian to signal the return to action by a second ring of the bell: ring, pause, ring, resume. Often the guardian, or the person who asked the guardian to ring, will speak a few words about why—“I thought we had speeded up and stopped listening” or “I needed to take a breath.”

Over and over again in the years since Calling the Circle was first released, we have found the guardian to be central to the PeerSpirit process, particularly in those inevitable times when tension arises. Anyone may ask the guardian to ring the bell at any time. This is one of the ways that leadership rotates in a circle. One person holds the responsibility of guardian, and others help. The bell becomes a voice in the circle that honors the process.

Scribe

Not every circle requires a record of its process, but when such a record is wanted, the role of scribe can be activated to help gather these insights. There are many creative ways to keep such a record: participants can work collectively with journals on their laps or individually on laptop computers, on chart pages spread out on table or floor, on a flip chart stand placed along the rim of the circle, or even on a wall on which papers can be pinned.

Like the guardian, the scribe sits in a more observational mode and listens for essence statements, new insights, and decisions rising to the fore. In the energy of heightened conversation, there is often a collective awareness that something significant has just been said. “Whoa, did we capture that? Who’s scribing?” is a common comment at these moments. We like to use the word harvest, rather than report, for recording these insights. At the conclusion of circle time, a collective harvest may be part of check-out: “What did you hear today that you take away as your primary learning?” is a harvest question. And if no scribe has been writing earlier, the host may ask someone to take on that role during closure.

The role of scribe is not the same as that of a minute-taker. If minutes are required in an organizational context, circle members need to discuss how to handle this because the intensity of minute-taking and the required detail and accuracy greatly limit the ability of the person to participate fully in the gathering, thus making it an unsuitable role for the scribe to fulfill.

Forms of Council

There are basically three forms of council: talking piece council, conversation council, and silence. The principles, practices, agreements, guardian, and center are essential in each form.

Talking piece council is a more formal pattern of speaking and listening. When engaging a talking piece, permission to speak passes from person to person. One person speaks; the group listens. The purpose of talking piece council is to hear each voice, to garner insight and show respect for each person’s presence, to seek collective wisdom, and to create consensus. These are the ancient practices of circle process. As the talking piece passes around the rim, the commentary often takes on a spiraling quality, gathering depth and calling people one by one to increased clarity.

Talking piece council is often used during check-in so that every person has a way to participate verbally and to signal the shift from socializing to circle. In talking piece councils, people have a chance to witness the stories each member of the circle wishes to share. When used to elicit responses to a specific question, each person speaks without necessarily making reference to what others have said.

Conversation council is employed when people desire a more informal structure or a quickened pace of contribution and response. In conversation council, as in ordinary conversation, people pick up on what others are saying. They react, interact, brainstorm, disagree, persuade, and interject new ideas, thoughts, and opinions. The energy of open dialogue stimulates the free flow of ideas. There are times when conversation is essential to circle process and times when circle will work better if it’s slowed down a bit, allowed a calmer pacing and more contemplation.

The two forms of verbal council shift back and forth according to need and may hybridize such as when tossing a Koosh ball from speaker to speaker.

Silence has not usually been considered a form of meeting except in meditation settings. However, silence in circle is an important way to support deepened thoughtfulness. Silence provides time for members to write in their journals together or respond in writing to a pertinent question. It can also be a time for inward centering that is shared collectively. A host might say, “This is an important moment for us as a group. Let’s take a moment of silence to be thoughtful. Guardian, would you ring us in and out, tending to time?” A few minutes of silent council can be an incredibly effective centering tool before or after a longer talking piece council.

Silence in most social settings, especially in business, can convey many different things, and people may be uncomfortable unless a context is set. When silence occurs spontaneously in reaction to something that has happened, it is helpful to have it named and welcomed. The host might say, “It seems we don’t know what to do or say next. We’ve fallen silent, so let’s welcome this pause and hold our peace until the way forward is clear.”

Consensus and Voting

People often ask us, “Can a circle make a decision? How does a circle make a decision?” Consensus is a process in which all participants have come to agreement before a decision goes forward or action is taken. Consensus is applied when a group wants or needs to take collective responsibility for actions. In a PeerSpirit group, there needs to be a sense that everyone supports what the circle is about to do. Consensus doesn’t require that everyone have the same degree of enthusiasm for each action or decision, but it does require that each person approve the group action or is willing to support the action the group is about to take. Consensus provides a stable, unifying base. Once consensus is reached, the circle can speak ofits actions as “we.”

One way to signal consensus is to institute a thumb signal:

thumb up = “I’m for it.”

thumb sideways = “I still have a question.”

thumb down = “I don’t think this is the right way for us to go.”

Clarifying conversations occur, led by anyone with a sideways or downward thumb. Although the downward thumb indicates disapproval, it may not necessarily block action. With further conversation, the person may actually be willing to say, “I don’t support this action, but I support the group.” Keeping dialogue open in the middle of the thumb vote allows for continued insight and learning, and the decision made is stronger by including space for hesitancy or resistance.

Consensus can also hybridize according to a circle’s needs. Some groups operate with a consensus-minus-one philosophy. Group members listen carefully to the dissenting voice, and if the group remains confident in its decision, they honor the principle to move ahead so that no single person can stop a decision.

Check-Out

Having opened the circle with respect, it is equally important to close in a way that signals the circle’s completion. Because heightened attention is required to listen and speak carefully in circle, people want to know when to relax. Before closing, the host may invite the participants to revisit their insights, action items, or agreements, especially if there is need to clarify confidentiality..

A common circle closing invites a brief check-out so that every person has a chance to speak briefly what he or she has learned, heard, appreciated, or committed to doing. The circle may want to designate the host for the next meeting and pass along certain duties in order to maintain coherence. Final closing may then be offering a quote, poem, or brief silence, followed by the bell.

We’d like to return to the seventy-fifth birthday circle Ann organized for her parents, mentioned earlier in the chapter. After an hour of talking piece council and dozens of thoughtful, funny, and sometimes poignant stories, Ann closed the circle with a rousing rendition of “Happy Birthday.” Immediately after the song ended, cacophony erupted in the room. The measured cadence of story sharing was over. It was time for chatting, refreshments, and release from careful listening. Bring on the cake!

It may not be anyone’s birthday, but this sense of celebration at good process well done is often alive in the room. In the egg-shaped staff meeting circle, even though people had been vulnerable and the company had had to make some difficult decisions that affected people in the room, participants left the meeting in good spirits, able to get on with their day, knowing that they had been listened to and feeling pleased with their contribution to the conversation.

Coming Full Circle

Circle structure is intuitive. Once we begin these practices, we remember this way of being together. There is a fundamental familiarity with circle process from our long social history that is lying dormant, just waiting to be reactivated. Over the years, we have experimented with a number of ways to communicate this basic structure. The longest versions are book-length. The medium-length versions are this chapter and our self-published booklets. On our Web site, the two-page downloadable document, “Basic Circle Guidelines,” is available in a growing number of languages. And we have fit the most essential elements onto one side of a business card. The chapters in Part II elucidate these components with further insights and stories. We will keep exploring how the circle’s bones will hold you and hold the group—they are weight-bearing, and they are strong.

So now you have the operator’s manual. You have assembled the knowledge needed to start hosting. Just try it. We can check in and check out with each other in almost any environment, and doing so will improve the quality of our connections. We can begin to shift our engagement at work, at home, and in community organizations from competition to collaboration simply by how we show up and contribute and the things we acknowledge about what’s going on. We can live the agreements, principles, and practices—whether or not they have been introduced to the group we’re in. When we show up differently, different things happen. People get curious.

Curiosity is an effective model of circle introduction. Several years ago, we offered a one-day circle training with a group of beleaguered managers who were not sure if they dared take this back to their departments—they feared resistance and were unsure of their skills to really hold to the form. The group came up with the idea that they should start by practicing with each other. They decided to host monthly manager meetings in circle in order to gain confidence in their hosting capacities, and they adopted an agreement that they could stop action and talk about the process while practicing it. The managers met in the education room near the reception area where there was space to make a circle of chairs. They experimented with how to blend needed topics of conversation with needed time to get to know each other better. Sometimes the tenor of the meeting was hushed with emotion or poignancy, and other times the inviting sounds of raucous laughter leaked under the door. Even though the janitor told the receptionist who told the departmental assistants that occasionally there was a lot of Kleenex in the waste bins, people noticed that their managers seemed happier and more focused after these meetings. People began to ask, “What are you doing in there?”

Pretty soon the managers were ready to say, “We’re practicing circle. Want to join us?”

Practicing is the key. Circle is not a succeed-or-fail environment: it is a constantly shifting, imperfect, self-correcting learning field. “What if I mess up?” is a common concern. Well, the guardian is there to pause the process and invite the group to inquire with curiosity:

![]() What’s not working here?

What’s not working here?

![]() Why isn’t it working?

Why isn’t it working?

![]() What are we willing to do about it?

What are we willing to do about it?

![]() What’s our wisdom?

What’s our wisdom?

You, the host, are not succeeding or failing: we, the whole circle, are learning. This is the shift: the host is not like the driver of a car, steering all alone and responsible for whether or not the vehicle stays on the road or crashes into a tree. The whole group is steering. Everyone is connected to the hub of the wheel. And most of the time, most of the people want the process to work, want the host and guardian to offer the level of guidance needed in the moment, and want everyone’s participation to be received and meaningful. Most people would rather learn from little readjustments of course than wait until problems become big swerves necessary to avoid impact.

In the fully participatory model of PeerSpirit Circle Process, everyone will eventually take a turn as host, guardian, and scribe; everyone will serve as leader of an agenda topic, holder of a question, and spinner of synergy. This inclusivity of risk taking creates a strong desire to support whoever is serving as leader at the moment. We are going to want similar support when our turn comes.