CHAPTER

4

Rotating Positions of Leadership in the Circle

A PeerSpirit circle is an all-leader group, in which positions of responsibility change and adapt as needed. The three most identifiable positions of host, guardian, and scribe hold the progress of a circle session while all participants hold the infrastructure.

A small Zimbabwean woman named Sikhethiwe (pronounced “Ski-teeway”) leaned forward in her handmade wooden chair and said to the guardian, “Stephen, ring the bell.” Stephen rang a tingsha, held the pause a few seconds, and rang it again. All twenty-four of us, brown and white faces, young and old, paused in our talking under the thatched-roofed, open-walled meeting house in Kufunda village. After the second ring, our young host said to her guardian across the circle, “I don’t know what to do next. What do you think we should do?”

With the rest of us quietly observing, Sikhethiwe (the host) and Stephen (the guardian) held a dialogue across the circle about where to take their leadership around a community issue we were discussing. After a few minutes, they decided to pose a question to the group: “Is everyone ready to vote on whether to offer leadership training to surrounding communities next month?” The group nodded. Sikhethiwe asked for a “thumbs vote,” and soon the group had made a decision and was ready to move to a new topic, which was to be hosted by a new host and guardian. We took a break, and while most of the group scattered out into the sunshine, Sikhethiwe and Christina (scribe) spread flip chart paper on the floor and recorded the important points of conversation and the decision the group had made. The sheets were posted next to the day’s agenda for all to read.

This interaction is an excellent model for the three positions of host, guardian, and scribe within a circle:

![]() The host and guardian work together in leading a meeting; the host’s role is more verbal, though both are tending group process.

The host and guardian work together in leading a meeting; the host’s role is more verbal, though both are tending group process.

![]() Transparency in circle leadership is helpful to the learning curve and therefore supported by the whole group since group members know that their turn to hold these roles is coming sooner or later.

Transparency in circle leadership is helpful to the learning curve and therefore supported by the whole group since group members know that their turn to hold these roles is coming sooner or later.

![]() The pause offered by two rings of the bell gives everyone, especially the host and guardian, a chance to reflect on the direction the conversation needs to go in order to reach a sense of completion.

The pause offered by two rings of the bell gives everyone, especially the host and guardian, a chance to reflect on the direction the conversation needs to go in order to reach a sense of completion.

![]() The scribe volunteers to record highlights, insights, and decision points so that the essence of circle process is preserved and the group has a history of itself.

The scribe volunteers to record highlights, insights, and decision points so that the essence of circle process is preserved and the group has a history of itself.

![]() The thumbs vote asks those in favor to point their thumbs up, those with remaining questions to hold their thumbs sideways, and those who are opposed to signal with their thumbs down. Those with questions or those opposed are invited to explain their vote. It is a form of modified consensus building common in PeerSpirit Circle Process.

The thumbs vote asks those in favor to point their thumbs up, those with remaining questions to hold their thumbs sideways, and those who are opposed to signal with their thumbs down. Those with questions or those opposed are invited to explain their vote. It is a form of modified consensus building common in PeerSpirit Circle Process.

PeerSpirit invites an equality of presence, contribution, and responsibility that is shared out among all members of the circle. Rotating positions of leadership within this collegiality greatly enhances everyone’s experience. The circle remains peer-led, and peers take on temporary positions of authority that support presence, participation, and accountability. Host, guardian, and scribe become the pattern holders. They lead from within the rim of the group and work together to assist in holding the social container, tending intention, and moving through the process.

The Role of Host

In the early years of PeerSpirit work, we experimented with flattening the triangle completely, with leadership roles disappearing into the rim. This didn’t work very well because leadership would spontaneously emerge and people would take on functions that shaped group process whether or not these roles had been named. However, we didn’t think that naming someone the “circle facilitator” accurately reflected what we were learning about the qualities of collaborative conversations in circle.

The word facilitator often connotes a position that is mostly outside the group. A facilitator comes in to help a group or organization but does not join the group or organization. In these early years, we were in the middle of developing a new model for circle process, and we didn’t have a name for where we wanted to go. Then, in the international collegiality growing out of the From the Four Directions initiative, the phrase “circle host” began to come into play. We recognized it as exactly the term we needed. A circle host is like the host of a dinner party. The host cooks the meal, sets the space of welcome, and when people are gathered, both serves and sits down to partake of the feast. The host does not stand aside and observe while others partake. The host is not trying to facilitate other people’s experience while remaining an outsider or expert. The host joins the group process while maintaining and observing the pattern.

The person serving as circle host provides continuity from one meeting or topic to the next and gently assists the microstructures of the conversation.

![]() The host sets up the room, placing chairs or seats in a circle, creating the center, posting agreements, intention, and so on so that participants enter a prepared space of welcome.

The host sets up the room, placing chairs or seats in a circle, creating the center, posting agreements, intention, and so on so that participants enter a prepared space of welcome.

![]() The host helps the circle abide by its agreements and fulfill its intention.

The host helps the circle abide by its agreements and fulfill its intention.

![]() The host is granted temporary leadership authority by circle members to guide group process and work in conjunction with the guardian.

The host is granted temporary leadership authority by circle members to guide group process and work in conjunction with the guardian.

![]() Typically, the host and guardian sit opposite each other so that they can see each other and observe both sides of the circle.

Typically, the host and guardian sit opposite each other so that they can see each other and observe both sides of the circle.

This ability to serve the group and at the same time participate in the group is the essence of leadership from the rim. The redefinition of where leadership sits and how it offers guidance instead of asserting authority is the paradigm shift to which circle calls us. Leadership is understood to be a temporary authority, a stewardship of group process, a donation of one’s skills, focus, and energy so that the collective well-being is tended and the inherent wisdom in the group may emerge. Circle leadership assumes that everyone in the circle may hold this position at some time in the process.

The role of host also acknowledges how hierarchy can helpfully and healthily appear in circle process: the triangle is always present—and always shifting. When people lean forward to help each other, to move the conversation forward, or to make a contribution—they assume increments of leadership. These are acknowledged, and then the process moves on. For an hour, Sikhethiwe is host; then Fide takes a turn, and then Silas, and so on. The circle is stabilized within this spirit of voluntary contribution.

In the council of community members at Kufunda village, the various topics in need of discussion were laid out for all to see—like pieces of a pie. Coming from another culture and country, we were serving as coaches to their adaptation of PeerSpirit circle. We had traveled to Zimbabwe to honor the challenges and strengths of circle self-governance and to help increase the villagers’ confidence in their own circle skills. We would teach the Components of Circle and then lean back so that their leadership could lean forward; we would suggest and ask for their suggestions. This openness gave them opportunities to practice without a sense that they had to do things in a certain way: everything in circle became a lesson that served the ongoing cohesiveness of their community life.

After a break, Sikhethiwe led a short discussion on what had been decided during her hosting and then passed her role on to another person in the circle. Stephen handed the bells and the role of guardian to someone else. New leaders stepped in to guide and scribe the next topic.

Hosting in Conflict

There are many creative ways to host a circle. Our German colleague, Matthias zur Bonsen, was confronted with a challenging situation when asked to help a company in conflict host a circle of 140 distressed franchisees.1 Matthias explains:

“Private Tutoring is a billion-euro business in Germany. Students who do not make a passing score have to repeat the current year of schooling, so parents are motivated to help their children maintain satisfactory grades. There are two big companies that offer their services nationwide. These companies tutor students in groups of three to five.

“One of these companies, which has around one thousand outlets throughout Germany, wanted to intensify the collaboration with its franchisees. To achieve this, the company decided that the governing board that represented the franchisees needed to meet more often with management. And to make this economically feasible, it was proposed that the board size be decreased from twenty to six members and that those six be reimbursed for their increased investment of time. This required new bylaws.

“A small group of franchisees met with management and created a proposal for the new bylaws. And then the conflict began. Many franchisees didn’t like the idea. They were afraid that their region wouldn’t be represented in the smaller board. Put to a vote, the new bylaws received only 60 percent approval. An emotional, somewhat aggressive, and hurtful discussion between franchisees in their Web-based forum generated more confusion and resistance. For company management, letting the majority rule was simply not an option: the company did not want to lose the consent of 40 percent of its franchisees.”

The company called in Matthias and his colleague, Jutta Herzog, who are well known in Germany as pioneers in the field of large group interventions. Since 1994, Matthias has written three books and brought Open Space Technology, Future Search, Real Time Strategic Change, Appreciative Inquiry and World Café to Germany; in 2007, he brought PeerSpirit Circle Process. After considering the situation, he and Jutta decided to host a circle.

Management invited all franchisees to a meeting from Friday noon to Sunday noon. This had never happened before. One hundred forty of them decided to attend. The most critical part of this conference was a whole-group dialogue about the conflict concerning the new bylaws to be held on Saturday afternoon. When using circle in a large group, hosting has to become very creative—it’s like jumping from a dinner party to catering: there’s more planning to make sure the quality of engagement will hold. Yet when every voice needs to be heard at first hand—and in this situation, that was essential if the conflict was to be resolved—the circle can expand to hold a large community conversation.

Matthias and Jutta designed a center with special significance to the group. They constructed a pyramid of sixteen red boxes, which was approximately 3 feet (90 cm) high. The box at the top symbolized the purpose of the company (including the franchising system). The four boxes in the middle level stood for its values. And the nine boxes at the bottom symbolized its goals. The whole group had worked on purpose, values, and goals in the preceding parts of the conference and understood the meaning of the boxes. Then Matthias and Jutta arranged 140 chairs in four concentric circles, like the rings of a tree.

Matthias reported, “On the box at the top of the pyramid we placed a microphone. This served as our talking piece. We explained the purpose of the talking piece and asked everybody to put the microphone back on the ‘purpose box’ after each person had spoken. (We thought that everybody who wanted to speak should be connected with this ‘purpose box.’) Then the dialogue began. Franchisee after franchisee came into the middle of the circle, took the microphone, and spoke.”

He recalls, “In the beginning, the participants repeated their entrenched positions. Very slowly this changed. Some of the franchisees, who spoke in the middle time, were able to speak from their heart. This changed something in the group. The dialogue in the large circle lasted 105 minutes, and the energy level was high during this whole time. Then it became obvious that a solution had been found.” Matthias and Jutta listened for the shift in group consciousness and consensus. They hosted the space for the circle process to do its work. They served as guardians. They served as scribes.

At the conclusion, for legal reasons, a vote was necessary: 137 out of 140 agreed to the bylaws change, with 3 abstentions and no votes against the solution. After this circle process, the mood in the group was euphoric. The franchisees had a pool party in the evening, and Matthias reported, “They danced, jumped in the water with their clothes on, danced again. … The circle had worked.”

Guardian

The guardian is a unique contribution from PeerSpirit Circle Process that is now being adapted in other conversation modalities. As explained in Chapter 2, the purpose of guardianship is to hold a place for mindfulness and intervention in a circle meeting. The person serving as guardian is an energy watcher and observer of both spiritual and practical needs and often an intuitive guide for honoring conversational process.

![]() The guardian serves as a conscious reminder of the energetic presence that joins people once they are seated in the container of circle process.

The guardian serves as a conscious reminder of the energetic presence that joins people once they are seated in the container of circle process.

![]() The guardian helps the circle fulfill its social contracts, timeliness, and focus.

The guardian helps the circle fulfill its social contracts, timeliness, and focus.

![]() The guardian is granted ceremonial authority by circle members to interject silence and recenter group process.

The guardian is granted ceremonial authority by circle members to interject silence and recenter group process.

The holder of the bells rings the bell twice—first to call for a pause in the action and then, ten to twenty seconds later, a second time to end the pause. The guardian (or whoever has asked the guardian to ring the bell) enunciates the reason for calling the pause.

The guardian’s role is to pay close enough attention to the nuances of interaction that he or she is prepared to intervene in helpful ways. The insertion of pauses ranges from calling for a stretch break to noting the passage of time to marking a space between speakers to making corrections of course—restating agreements, restating the topic or intention, and intervening in moments of destructive tension. Anyone can call for the bell and initiate the pause. The significance of this shared responsibility and how it democratizes circle process shows up throughout our work, over and over.

When someone is rambling on during a check-in that was framed as a chance to speak a few sentences of arrival, the talker has the talking piece and everyone is fidgeting. Here the guardian might wait for the speaker to take a breath, ring the bell, pause, ring, and say, “I call us back to understanding that this is a brief round in which to make sure every voice is heard as we begin.” The person who is rambling may be momentarily embarrassed and is also usually grateful to have a graceful way to come to a conclusion and relinquish the talking piece.

Guardianship in Response to Conflict

At a university faculty training session, a classic need for intervention occurred late in the day. Everyone was tired and ready to be finished. Christina was teaching alone, and a volunteer guardian had just set the tingsha bells in the center, anticipating a break for dinner. A professor who had been hostile to the process off and on all day seized the moment and turned on Christina: “I don’t get this circle stuff. In my way of thinking, you have abdicated your responsibility as leader. You’ve lost control of the group. We haven’t made a single decision. What the hell are you doing here?”

The guardian looked panicky because she had no way to intervene. The room went into temporary shock. The youngest circle member, a department secretary who had been present as scribe, took on her personal power, grabbed the bells from the center, and rang them loudly. This gave Christina and everyone in the room time to sit up, pay attention, and collect their thoughts. When the secretary rang the bells again, she said, “We have an agreement about withholding judgment. And we are all too tired to talk about this now.”

While the young woman spoke, Christina had a chance to think. She thanked the young woman and invited her to serve as guardian until the circle had truly disbanded. To the professor she said, “It is not my job to control this group. It is the job of the group to learn how to function as a collaborative circle. This is a training session. In any training, we wobble toward confidence and competence. Tomorrow we are scheduled to do more agenda-based work with shared leadership from your colleagues. It’s my sense of the group that people have done all they can manage today.” People nodded their heads. “So as host, I’m closing the circle. I invite you all to remember our agreement that what’s said here remains here. Have a good supper, relax by the fireplace, and get a good night’s sleep. Let’s suspend judgment and show up here at nine tomorrow morning. Brenda, great guardianship. Please ring us out.”

One of the skills of the guardian role is to practice naming the situation with neutral language. Neutral language requires the ability to talk about what’s happening without instigating shame or blame. The guardian seeks to avoid personalizing or polarizing a moment in circle process by being able to call the group back to the infrastructure in place: the agreements, principles and practices, intention, and use of center for grounding. Brenda did this beautifully when she grabbed the bells from the center. She used neutral language and gave Christina time to compose a direct, yet uncharged, response. Christina’s response is one of many that are possible. It was the host’s wisdom that was being challenged in this instance, and the man was not likely to be easily placated. The faculty circle would need to learn how to manage his negativity without rising to the bait and to hold him accountable to their agreements.

In moments of tension, conflict, or surprise when the guardian needs to intercede, the pause is needed to help everyone get recentered on the rim and focus on the center to stabilize the circle container.

Several years ago, we were in a business setting participating in a circle check-in around the question “On the way to work this morning, what did you observe that made you thoughtful?” One of the participants spoke about the “crazy people” hanging out on the lawn of the city library where she had stopped to return some books. There was no intended malice in her statement; her remarks were focused on not feeling entirely safe around the library steps. An alert guardian saw a man on the other side of the circle wince and turn ashen. The guardian rang the bell for a pause and looked at her colleague. He gave her a barely perceptible shake of his head—apparently not wanting attention. Not sure what to do next, the guardian said, “I honor Debra’s observation and invite all of us to be compassionate of the challenging lives of street people.” The check-in continued with other anecdotal stories.

By the time the talking piece traveled around to the man, he spoke with emotion. “One of those crazy people on the library lawn is probably my twenty-eight-year-old son. He’s schizophrenic. Sometimes he has a little room somewhere; sometimes he’s on the street. He’s not violent, but most people have no way of knowing that. Not a single day passes that my wife and I don’t worry about whether or not he’s taking his meds and staying safe. Sometimes on my way to work I drive around that part of town, by the library, under the freeway viaducts, just looking for him, to see if he’s still alive.” His voice shaking, the man continued, “Those ‘crazy people’ come from somewhere. They belong—or used to belong—to someone. When you can, look in their eyes and say hello. When you can, send them good wishes.”

He passed the talking piece to his left. The woman whose turn it was to speak next didn’t know what to say, and Debra looked stricken. The guardian rang the bell and let the pause linger in the room, rang again, and said, “Thank you, Frank, for the reminder that we all carry complex stories. And that we are all connected.”

Debra leaned forward and said, “Oh, Frank, I had no idea you were carrying this burden. Thank you for telling us. And I promise you, I will see these people with more understanding than ever before.”

The woman holding the talking piece took a deep breath. “Wow,” she said. “That was big. … Are we really ready to move on?” Frank and Debra and several other people nodded, and the check-in round was completed.

Especially in moments like this, the bell serves as a voice in the circle. The guardian is watching for release of energy, for readiness to pause and readiness to resume. Though the guardian is holding the bell, anyone in the circle can call for a ring and pause. If Frank had been ready to speak right after Debra, he could have asked for the bell and shared his feelings immediately. Notice that even though a talking piece was in play, Debra leaned in with a direct response to Frank before the circle went on: the circle’s conversational structures are intended to serve group process, not to dominate it. The art of circle practice is to hold the pattern loosely when that serves the moment and tightly when needed for support.

After all the members in Frank and Debra’s circle checked in, the host, noting that the first agenda item was a conversation about budgets, asked the guardian to ring the bell and questioned the group: “This has been a poignant check-in. I’m not sure we’re ready to jump into number crunching. Where would the group like to go next?”

Frank spoke up. “I am really fine—glad this secret is out in the open. I can move into agenda.”

Debra spoke. “I’m having a thousand thoughts that are not about the budget. I’d like a little break.” The group decided to take a stretch before proceeding.

This became a defining moment for the team, often referred to as “the moment we came together.” Over the years, they continued to share authentically about their personal lives and to face challenging decisions with cohesiveness and depth.

In Kufunda, translating back and forth between Shona and English, we noticed that people were pronouncing the word guardian as “guide on.” We were charmed and realized that they had captured the true essence of this role. The guardian is a guide.

Guides in the wilderness use skills that cover the full spectrum from first aid and camping survival to encouraging the awe that comes from immersion into nature. So in the circle, the guardian is a guide who watches for what is needed, from the practical to the spiritual.

Scribe

One of the challenges in circle process can be catching the essence of the conversation so that we can communicate this to others or notice when a decision has been made. In traditional meetings, someone is often assigned the note-taking function and decisions are moved, seconded, and voted on according to Robert’s Rules of Order. In circle, too, there can be a need or desire for someone to take notes and record insights, decisions, votes, or consensus. How this happens in the flow of circle process and what is produced and shared (or not shared) vary greatly according to the nature and setting of each circle. When called for, the scribe becomes the third point on the inner triangle of leadership at the rim.

The person serving as scribe serves as record keeper or historian in circle process and may be the first one to articulate emergent wisdom, decisions, or completion.

![]() The scribe negotiates with the host and guardian regarding what is needed as a record of the process.

The scribe negotiates with the host and guardian regarding what is needed as a record of the process.

![]() The scribe is looking for essence, not trying to provide a transcription.

The scribe is looking for essence, not trying to provide a transcription.

![]() The scribe uses writing tools as appropriate to the group: notepad, journal, laptop computer, or flip chart.

The scribe uses writing tools as appropriate to the group: notepad, journal, laptop computer, or flip chart.

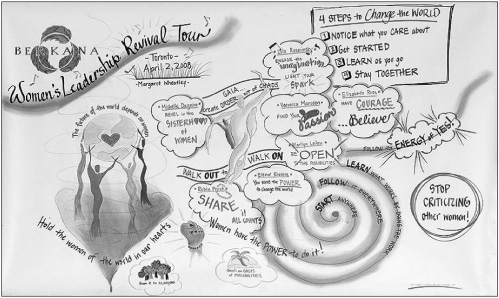

![]() A standing scribe and flip chart may be included in the rim of the circle, or a group may choose to hire a graphic recorder to create a chronology of words and images.

A standing scribe and flip chart may be included in the rim of the circle, or a group may choose to hire a graphic recorder to create a chronology of words and images.

![]() The scribe keeps what is recorded confidential and ensures that this agreement is scrupulously observed.

The scribe keeps what is recorded confidential and ensures that this agreement is scrupulously observed.

The scribe function may also be ascribed collectively such that all participants have journals dedicated to noticing their own thought process during the circle’s ongoing work. These journals may contain notes on the contributions of others that the writer wants to comment on or notes regarding decisions, options, directions, and personal reactions and reflections. Circle journals are usually eclectic private records that are shared voluntarily or not at all. And yet when someone has a question about what occurred a session or more ago, there’s a record somewhere in the rim of the circle. Participants have stated the helpfulness of journal keeping as a way to jot down ideas and return to listening while waiting their turn to speak.

Some circle gatherings require no scribe, and to put someone in that role would feel awkward. However, even in the most casual ongoing groups, people may desire some kind of record of their journey together. In an annual women’s retreat, Christina records the essence of people’s check-ins and the final checkouts in her journal. The following year, she brings this volume back to help the group remember where it was a year ago. Our friend Cynthia is known throughout the community as a note-taker who enjoys scribing for the circles she’s in. “It’s just how I’m wired,” she says. “For some people, writing can distract their attention, but for me, when I’m writing things down, it brings me fully present.” Other groups have experimented with creating collages of their experiences, putting together scrapbooks, and using digital storytelling or Internet social networking.

FIGURE 4.1

When Margaret Wheatley brought the Women’s Leadership Revival Tour to Toronto, Ontario, a visual practitioner, Sara Heppner-Waldston, recorded the event in such a way that the memory of the evening would resonate whenever someone looked at her imagery (see Figure 4.1), and for those who were not present, the imagery could provide a sense of what had occurred. We need something to reattach us to the string of inspirational, thought-provoking, and heartfelt moments of circle. It’s not a Matter of being fancy; it’s about anchoring the process of collaboration, which can become such a synergistic experience that we forget what actually happened because that wasn’t the part of our brains that were most deeply activated.

When the host, guardian, and scribe meet before a circle meeting or when the group gathers around its intention, thinking about what is wanted from the harvest is an important frame for the conversation. In the drawing, the sponsor, event, date, participants, and major speech points are recorded. In a different circle, the history of a decision may be needed.

The leading-edge thinking about how to understand the “art of harvesting” these highly synergistic conversations has emerged from the Art of Hosting network. The Art of Hosting Web site (http://www.artofhosting.org/thepractice/artofharvesting) maintains an evolving downloadable guide to harvesting collaborative conversations that is an incredibly valuable tool. This work is being led by Monica Nissen of Denmark and Chris Corrigan of Canada.

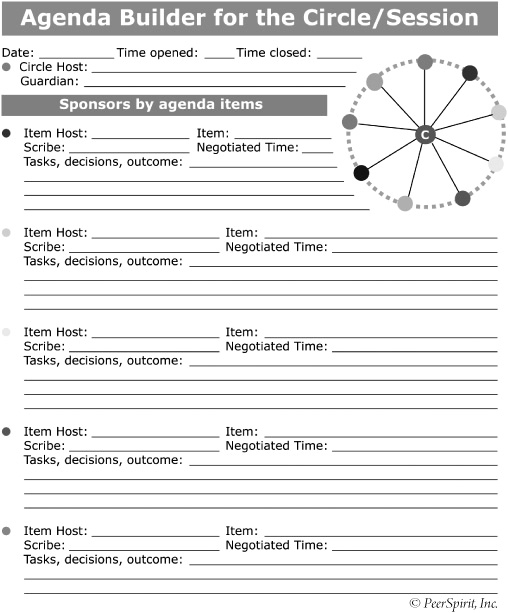

Circle and Agenda

The host, guardian, and scribe roles are extremely helpful when circle process is combined with an agenda. There is usually a host of the meeting—one person who provides the kind of oversight mentioned throughout this chapter. The host sets up the space, offers a start-point, oversees check-in and check-out, and guides the overall process. Usually, the host also steps into a leadership role to steward each topic identified as an agenda item. The topical host brings needed information, communicates on paper or electronically, and designs a group process for his or her part of the circle meeting. None of this thinking is reflected in the usual flat sheets of agenda items, so the administrative circle at Fairview Health Services designed a chart that would serve the organization’s needs (see Figure 4.2). We have carried this diagram to other organizations and invite readers to continue to use and adapt it to fit your needs.

As the agenda is constructed, time is allotted, and the need for scribing is determined, circle process blends the need for tangible outcomes with the softer elements of community building. For example, someone hosting an agenda item may negotiate by saying, “I need ten minutes to present the new space assignments for integrating two departments on one floor. I need everyone at our meeting to have a cubicle chart, to engage with comments and questions, and to take our chart back to your departments and get final feedback from those being shifted. Knowing we are going to get input from the staff being combined, I’d like to devote another ten minutes to generating ideas for creating an atmosphere of welcome so that this change is as pleasant as possible.”

“Who’s in charge?” is a question many people carry into a meeting; circle process leads us to ask, “How are we in charge?” This is the question that allows us to explore the relational core that binds us to one another in service to intention.

And then the deeper question “How are we not in charge?” invites us to honor the emergent wisdom collected at the center, experienced by the host, recognized by the guardian, preserved by the scribe, and held by all who are present.

Throughout this book we talk about circle as a container, holding space for each other in this form. We can provide this sense of holding space in person, over the phone, and even in written Internet conversations. However we do it, the roles of host, guardian, and scribe stabilize the environment so that our best offerings come forward.

FIGURE 4.2

Circle on the Telephone

Increasingly, as people use the telephone and computer-based communications for conference calls, “webinars,” and online classes, they want to transfer the quality of face-to-face experience to these settings. We find that the infrastructure of circle thrives in an aural environment—the difference is that the cues are no longer visual: they are spoken. On many conference calls, the host is established by having sent the invitation or intention beforehand. If the roles are not yet established, the first questions become “Who is hosting today?” “Who is guardian?” and “Who is scribe?”

The host will describe a center that is meaningful to the group and present a virtual talking piece. For example, “I’m sitting at my desk, and I’ve cleared away all the paperwork and created a little center here that consists of our intention and agenda for this call and I just turned on the LED tea light from our last board meeting table setting. I’m putting a small glass globe in the middle for our talking piece. I invite the guardian to ring us in.”

The guardian may say, “I’ve got the tingsha right here. I’m going to ring it about ten inches from my headset. Let me know if that’s the right level of sound.” Ring, pause, ring. “For our start-point, I’d like to offer a poem by Mary Oliver.”

After the poem, the host picks up the conversation and invites check-in. “Thank you for the poem. And thanks to Bob for volunteering to scribe for us. If you hear computer keystrokes, I’m assuming it’s you, Bob—let us know if you need help capturing something or want one of us to type when you’re talking. OK. I’ve got our group photo displayed on my laptop. We’re all smiling, and I hope that’s true this morning as well. Let’s check in from east to west around the question ‘What energy from our last meeting comes with you into this call today?’”

One by one, people introduce themselves and simply say, “I pick up the piece,” and when they’ve finished, “Piece back to the center.” As conversation progresses, the talking piece may or may not be formally used, and if things speed up or if voices are having a hard time breaking in on the conversation, someone will say, “I’m picking up the piece! We need to slow down a bit here, so I’m putting it back in play.”

At the end of the call, there is a brief check-out, and the scribe sends the harvested insights, decisions, and chronology of the conversation out by e-mail.

Holding the Space of Circle

As we practice, circle increasingly becomes an art of paying attention to ourselves, to one another, and to the conversation.

Our teaching colleague, Martin Siesta, was recently asked to describe the process of “holding space” that occurs in circle and other forms of collaborative conversation. He said:

“Holding space in circle means staying engaged and present with one another while we undergo a process of self-inquiry. We are listening and noticing each other’s contributions deeply, with empathy, and managing our own judgmental stream, bringing ourselves back to presence. This is a form of love—and it doesn’t have to be personal; it often occurs with strangers. When we love others in this way, we provide a space in which they can simply be able to feel what they need, to speak without worrying about how they will be perceived. It is a true gift. In some ways, it is seeing not only through someone else’s eyes but also in a way that transcends this. Perhaps a great example of this is in the video of the Three Tenors—the original from 1990—when Placido Domingo is singing ‘No Puede Ser’ and Zubin Mehta is conducting the orchestra. When I watch and listen closely, I notice how by ‘holding space’ for Domingo, Mehta is able to call out of the performer more than he dreamed possible. It is amazing—and at the completion of the song, there is deep recognition between them of how they served the other.”

That is the essence of host, guardian, and scribe in circle: they are holding space so that all present in the circle can reach inside ourselves and call out more than we dreamed was possible.