The Cost of Forgetting

To put a price tag on corporate forgetting is difficult but a team of U.S. academics has computed that project performance could be expected to retrogress to 52% of optimum output (Carlson & Rowe, 1976). In the United Kingdom, where low productivity is notoriously illustrated by the actual example of life imitating derision in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, where 16 workmen took nearly 4 months and £1,000 to change a light bulb in a street lamp and make its concrete post safe (The Sun, September 16, 2002). Alongside Proudfoot’s estimate of the cost of wasted productivity, cited earlier, a Capgemini research project found that British managers admitted that one in four of their decisions was wrong (one in three in the financial services sector; Capgemini, 2004); ironically these are outcomes that managers would likely not tolerate among their vocational subordinates. These performances suggest that the cost of experiential nonlearning in most countries outranks many of the other areas of managerial dysfunction in the workplace and should, therefore, attract more academic and workplace attention.

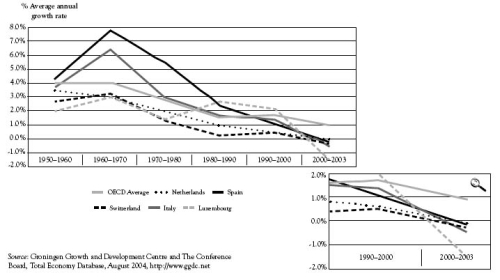

Figure 1. OECD’s productivity growth 1950–2003

Source : Groningen Growth and Development Centre and The Conference Board, Total Economy Database, August 2004, http://www.ggdc.net.

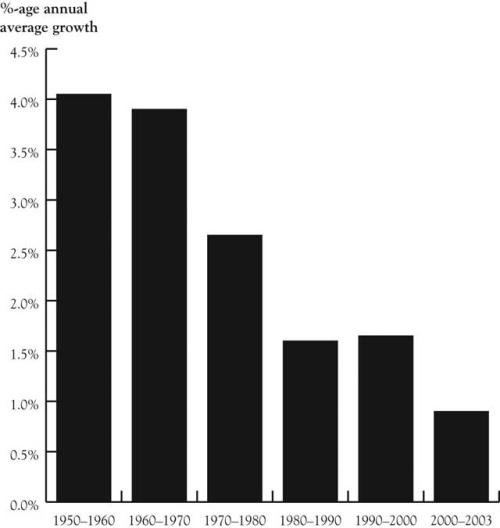

The relationship between productivity and decision making is explicit, and it is pertinent to ask the following deeply discomforting question of the 5-decades-old system that purports to groom the inheritors (although started in the late 1800s in the United States, business schools only came into wider service in the 1960s): namely, that if business education is supposed to help managers sell their employers’ wares more efficiently, how is it that managers in the 1950s and 1960s achieved higher productivity growth scores without any formal business education? (See Figure 1; Groningen Growth and Development Centre and The Conference Board, 2004.)

In terms of productivity, the United States has held the top position for much of the 20th century and, even today, is far ahead of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) pack by a significant margin. With a few exceptions (mainly the countries that have come up from a low productivity base), the rest are mostly struggling to inch ahead. The inside story across the board, including the United States, is one of declining annual growth rates, indicating that the developed world is quickly running out of steam.

It is useful to understand the difference between productivity and productivity growth. Productivity is the output produced per unit of labor, usually reported as output per hour worked or output per employee. Productivity growth is the increase in output not attributable to growth inputs such as labor, capital, and natural resources and it is driven by technological advances and/or improvements in efficiency. Over the long term, productivity improvements are the main contributor to rising living standards, otherwise called wealth. When productivity growth declines, the ability to compete weakens. When it falls into the red, it means that businesses are getting less than added value from their endeavors; new investment in many areas makes little sense and margins become increasingly difficult to achieve.

For productivity growth, the average figures for 2000 to 2004—a period of marked global growth—showed that, among OECD countries, Italy, Luxembourg, Holland, Spain, and Switzerland had moved into negative territory (see Figure 2; Groningen Growth and Development Centre and The Conference Board, 2004). The significance of these statistics is that this was the first time in modern industrial history that the productivity momentum had reversed among so many developed economies at the same time and with so many others in stalling mode. In the multifaceted world of productivity, this untrumpeted collapse is a late warning sign of systemic trouble for developed-world industry and commerce. It is now also an eleventh-hour alert that has been threatening for decades, with all remedial measures giving the patients only provisional respite.

In recent years management emphasis has been to maximize the efficiency of capital investment, specifically in technology. These tactics, however, have now virtually played themselves out. Workers employed in making and moving things accounted for a near majority of employees in the 1960s, whereas they now number less than one-fifth of the typical workforce, meaning that there are now too few employees in such jobs for their productivity to be decisive (Drucker, 1991). Employee numbers have been squeezed to the point where the human element of doing business has seemingly become almost mechanical. Interest rates in many developed economies may have come down from the high levels of the early 1990s but the capital factor is now so big that providers are demanding shorter-term returns. And although technology improvements look endless, the initial momentum that it provided for savings is ebbing quickly.

The responsibility for productivity and productivity growth is traditionally ascribed to workers, or more precisely to workers’ apparent lack of skills. In reality, though, their skill base has never been higher, opening up the more credible alternative that it is managers who are not giving full value to their employers. The way they are making their determinations is conferring little upside potential, which means that it is the decision makers who are leaving experience-poor competitors to step into the developed world’s experience-rich shoes. Exactly as Japan did in the 1960s and as the so-called BRICK countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China (especially), and Korea—are threatening now. As their development demonstrates, their ability to experientially learn, especially from others, is remarkable.