CHAPTER 7

Sustainability: The Current Lean Frontier

Looking back to the mid-1950s, it is relatively easy to understand how the challenging financial circumstances led Kiichiro Toyoda, Taiichi Ohno, Shigeo Shingo, and others at Toyota to pioneer the frequently cited seven Lean principles noted in Table 1.1 in Chapter 1. Upon reflection, the reader will understand that these seven principles were observed in a single facility and were aimed at internal organizational improvements and waste reduction.1 For example, internal activities, such as the accumulation of inventories, the movement of material, and the production of defective goods, result in the unnecessary consumption of resources.

Recently, sustainability has emerged as the evolutionary edge of Lean Management. Sustainability is a long-term objective that goes beyond internal improvements and waste reduction. Rather, sustainability is the current frontier of Lean with a broader scope. It extends Ohno's seven principles externally across the supply chain. It also further reinforces these seven principles as an integral element of an organization's culture.

This chapter examines sustainability. It begins with a definition of sustainability. This is followed with an identification of the eight economic drivers for its recent emergence. An examination of the three broad categories of sustainability initiatives, namely, product and process life cycle considerations; environmental stewardship; and facilities design, construction, environmental control, and maintenance, follows. The chapter concludes with some thoughts regarding the reluctance of firms to embrace sustainability as well as the future of sustainability.

Sustainability Defined

Sustainability has been defined and described in several ways, but it commonly refers to the characteristic of a process or state that can be maintained at a certain level indefinitely. The World Commission on Environment and Development articulated what has now become a widely accepted definition of sustainability, ‘to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’2 Sustainability addresses how processes and operations can last longer and have less impact on ecological systems. It is the conservation of resources, natural or otherwise, through sustainable activities and processes across a value chain. In particular, this relates to the societal concern over major global problems of climate change and resource depletion. Global problems and resource depletion can be addressed simultaneously through an examination of supply chain activities aimed at improvement, waste reduction, reduced resource consumption, and a reduction of transformation by various reclamation practices.

To date, most documented Lean improvement efforts have looked internally first, going after readily attainable improvements within a single transformation process possibly within a work center or department. If internal efforts are successful, only then have organizations focused on external initiatives. This evolution of Lean extends Ohno's observations beyond a single transformation process and beyond simple waste reduction. While sustainability promotes internal improvement and waste reduction within a single transformation process, it also encourages external improvement and waste reduction across the value chain. Furthermore, sustainability addresses waste reduction that may lead to improved social conditions on a global basis. Namely, Lean and sustainability are integral cultural characteristics of an organization.

It should be clear that non-value-adding activities consume resources, are wasteful, and over the long run are not economically sustainable. If an activity does not add value, it should be reduced or eliminated if possible. Processes and operations are less likely to be sustainable without improvement and waste reduction, as resources are typically increasingly scarce.

Many organizations, including, for example, Ford, General Electric, Toyota, Walmart, and others, have now included sustainability as part of their corporate objectives. Ford's ‘vision for the 21st century is to provide sustainable transportation that is affordable in every sense of the word: socially, environmentally and economically.’3 World-class organizations understand that they must continually reinvent themselves in order to maintain a competitive advantage.4 World-class sustainability initiatives must anticipate and preempt customer demands and changing environmental regulations.5 Even when it becomes known that a world-class organization's capabilities provide it with a competitive advantage, lagging competitors are typically slow to address this performance gap, as they are inextricably wed to their existing approaches and processes. Once a firm achieves a competitive advantage based upon particular competencies, it is difficult for competitors to replicate without going through the same long-term learning process.6

Sustainability is a capability that can enhance the value of a company.7 Once developed, it leads to a competitive advantage that is difficult to replicate without a long-term learning process. Sustainable companies conduct their businesses so that benefits accrue to all supply chain stakeholders; this includes employees, customers, vending partners, the communities in which they operate, and, of course, shareholders.

Sustainability's Eight Economic Drivers

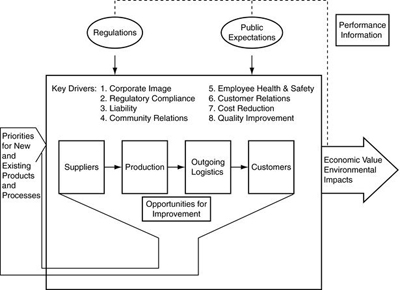

Although sustainability may have come about largely due to regulatory compliance requirements, a rising ratio of material to labor costs, as well as the opportunity to improve corporate image and community and customer relations, it has evolved into a much larger initiative. There are eight economic drivers for sustainability initiatives.8 These drivers, shown in Figure 7.1, may be broadly identified as enhancing image and compliance with regulations; future liability concerns; community relations; employee health and safety concerns; cost reduction or avoidance; and quality improvement. These drivers have encouraged firms to enlarge transformation process objectives beyond low cost, quality, speed of delivery, and flexibility to include a focus on social responsibility and employees.

Given these eight economic drivers, recent literature provides abundant examples of sustainability initiatives and their associated benefits. These initiatives have focused on three broad categories: (a) product and process life cycle considerations, (b) environmental stewardship, and (c) facilities design, construction, environmental control, and maintenance. Each of these is discussed in further sections with the use of industry examples and benefits achieved.

Figure 7.1. Sustainability and the extended supply chain

Product and Process Life Cycle Considerations

Product and process life cycle considerations examine ways to achieve sustainability objectives over the entire life cycle of a product. This includes practices affecting the design, development, manufacture, as well as reverse logistical flow of items in a closed-loop value chain. Two points regarding activities within this category need emphasis. First, firms implementing initiatives within this category often have more mature or advanced sustainability programs. Second, it should be emphasized that sustainability initiatives in this category often look externally, beyond the boundaries of a single transformation process across the entire value chain. The external focus of this initiative increases the economic returns capability for any one firm.

Firms are realizing that closing the supply chain loop with various reclamation activities for products at the end of their life cycle offers economic, social, and environmental value, often referred to as the triple bottom line.9 A change in the typical cradle-to-grave manufacturing model to a cradle-to-cradle approach, where new products are designed to help restore nature and eliminate disposal, has been proposed.10 The idea is to design products for extended use, reuse, refurbishing, remanufacturing, and eventual recycling. The use of these practices has been encouraged in part due to rising energy, commodity, and other material costs.

As an example, Ford has applied the triple bottom line concept in parts applications. Annually, Ford has reclaimed and reused 10.6 million pounds of crumb rubber in parts such as air dams, floor mats, trunk mats, and sound absorbers. This saved Ford $4.8 million in parts costs alone in just 1 year.11

The eco-design concept was introduced in 2001.12 Eco-design views sustainable solutions as products, services, hybrids, or system changes that minimize negative and maximize positive sustainability impacts, including economic, environmental, social, and ethical, throughout and beyond the life cycle of existing products or solutions, while fulfilling acceptable societal demands or needs. Eco-efficiency can be said to encompass the concepts of dematerialization, increased resource productivity, reduced toxicity, increased recyclability, and extended product life spans.

Examples of eco-efficiency are numerous. One simple example of dematerialization is the use of less packaging in shipping. A second example is Toyota's belief that hybrid technologies will play a central role in achieving ‘sustainable mobility.’ Partnering with many value chain participants, Toyota has made considerable efforts to promote the use of hybrid vehicles. By November 2007, Toyota achieved global cumulative sales of 1.25 million hybrid vehicles. The estimated resulting reduction in CO2 emission was 5 million tons. A third example is Toyota's efforts toward the development and production of lithium-ion batteries. These batteries offer the advantages of greater energy and output densities than nickel-metal hydride batteries in current hybrid vehicles.

Caterpillar has accrued financial benefits from recycling and remanufacturing tractor components like engines and gears. Its tractor components remanufacturing division, which has become its fastest growing unit in the recent decade, has annual revenues that top $1 billion. Furthermore, this division is estimated to grow 20% a year while reclaiming components that might otherwise be discarded.13

From these examples, it should be understood that reclaiming value from end-of-lease, end-of-use, and end-of-life product returns is achievable through closed-loop value chains. Reuse, recycling, refurbishing, and remanufacturing eliminate waste by reducing the number of times various transformation tasks are performed again. These practices reuse considerable portions of a product in a number of successive product generations leading to waste elimination and enhanced environmental performance.

Environmental Stewardship Initiatives

The second category of sustainability initiatives increasingly being pursued in industry is environmental stewardship. One significant change in the corporate practices over recent years is due to increasing demand for social responsibility as a result of global warming, resource depletion, energy and water shortages, solid waste disposal, and other environmental concerns. These concerns are increasingly attracting worldwide attention and, as a result, corporate stewardship of the environment is becoming a more important issue.

A growing awareness is emerging for the environmental stewardship role business must assume. One industry example is provided by Toyota, which is emphasizing the role of nature in creating production sites that are in harmony with their natural surroundings. Toyota is increasingly using renewable energy, including biomass and natural energy sources (solar and wind power) and contributing to the local community and conserving the environment by planting trees in and around manufacturing plants.

Enhanced environmental performance has reduced waste and improved processes, products, and profitability at several companies.14 Enhanced environmental performance leads to superior quality and ultimately improved profitability through higher customer satisfaction and loyalty.15 Simply put, there is a clear link between environmental management systems, practices, and operational performance.16

Various practices have emerged that emphasize this environmental stewardship role. Examples include industry-specific voluntary programs such as the Environmental Protection Agency's 33/50 program and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14000 environmental management systems standards program. Formerly adopted in 1996, ISO 14000 represents a framework to lead organizations to improved environmental performance. Results of a large-scale survey of manufacturers provide evidence that ISO 14000 can positively impact both the performance of a firm's environmental management system (EMS) as well as overall corporate performance.17 The survey results suggest plants can be both more environmentally responsible and more efficient with ISO 14000 certification.

Given the relative newness of this category of sustainability, it should not be surprising that the EMS in many firms has not been proactive, but rather reactive in nature. Findings suggest that the EMS is typically driven by changes in environmental regulations and that EMSs typically identify neither qualitative nor quantitative costs associated with environmental performance. Furthermore, environmental stewardship issues are typically internal initiatives, confined to a single facility, and are seldom extended to the value chain for activities such as supplier selection, retention, and evaluation.18

Facilities: Design, Construction, Environmental Control, and Maintenance

Increasingly, the activities of facility design, construction, operation, and maintenance are being conducted with an eye toward waste reduction and greater sustainability. One significant example of this third category of sustainability initiatives is Bank of America's One Bryant Park, the first skyscraper designed to attain a Platinum Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification. The design of the building will make it environmentally friendly.19 It will use technologies such as floor-to-ceiling insulated glass to reduce thermal loss and maximize natural light, thereby lowering energy consumption. A greywater system, which captures rainwater runoff and nonindustrial wastewater, will provide water for the building's cooling tower and toilets. Waterless urinals are estimated to save millions of gallons of water annually. The building will be made largely of recycled and recyclable materials with construction using a mixture of 55% concrete and 45% slag cement, a ground granulated recycled blast furnace by-product, which lowers greenhouse gas emissions through a reduced concrete production requirement. The air temperature cooling system will produce and store ice during off-peak hours, and then use this ice to help cool the building during peak load. The building even includes onsite power generation, thereby reducing significant electrical transmission losses that are typical of centralized power station production plants.

Walmart is incorporating various sustainable concepts in its retail building design, construction, environmental control, and maintenance. It is reducing the height of stores as well as tenant space, which reduces facility energy consumption. As a substitute for portland cement, the concrete used in the construction of the floors of its buildings incorporates 15–20% fly ash, a by-product of coal combustion produced by utility companies. It is specifying the use of the recycled fly ash, which makes the concrete stronger, reduces landfill waste, reduces the demand for virgin materials, and substitutes materials that may be energy intensive to create. Walmart utilizes various environmental control systems such as natural daylight dimming controls and electricity-generating photovoltaic cells in clerestories and skylights to sense and automatically regulate indoor lighting, heating, and cooling. At one retail installation, the skylights alone allowed lights to be turned off in the lawn and garden center for up to 10 h per day contributing to a $30,000 savings.20

Ford provides a third example of a company utilizing various sustainable concepts in building design, construction, environmental control, and maintenance. Ford's River Rouge plant has a 10-acre green roof that uses sedum, a succulent plant, to soak up 4 million gallons of storm water a year and to release it into a nearby wetland. It is estimated that this will double the length of the roof life, provide insulation, and will save Ford millions of dollars it would have had to invest in a water treatment facility.21

Summary: The Future of Sustainability

One should question why sustainability is not progressing at a faster rate among corporations today, given the wealth of benefits cited earlier and in the literature. Keep in mind that peoples' behavior toward adopting innovation occurs at varying rates. Innovations often require a lengthy period, sometimes years before they are widely adopted.22 Consumers largely drive the economic behavior of firms. Although the concept of recycling has been practiced for centuries, to date there are apparently still relatively few ‘innovators’ and ‘early adopters’ of this practice. Seemingly, the importance of this practice has yet to be fully understood by the majority of consumers. However, as the price of resources and the cost of proper disposal continue to rise, sustainability will naturally gain greater acceptance.

A second reason why sustainability initiatives are not as visible is that many initiatives are still only internal and have not included widespread value chain participation. The development of a world-class sustainable program typically proceeds in a stepwise manner.23 First, process-based capabilities are instilled internally in a single set (vertically) of transformation activities. Second, once mastered, the firm will seek to integrate and coordinate these capabilities across several activities (horizontally) or systems within the firm. Embedding these capabilities within the routines and knowledge of the firm making them multifunctional, organization-based capabilities follows as the third phase. Last, world-class firms will seek to make these network-based capabilities that reach outside the limits of the transformation process in order to encompass the value chain network. Increasingly, firms must reach outside their transformation process and include value chain partners in sustainability initiatives.

An interesting summary offering a staged taxonomy of sustainability initiatives has been proposed.24 The years 1970–1985 have been identified as the ‘resistant adaptation’ years where organizations found the least expensive means to minimally comply with environmental legislation. The second stage, the mid-1980s, has been identified as companies ‘embracing environmental issues without innovating.’ The third stage of the late 1980s consisted of ‘reactive’ organizations using ‘end-of-pipe’ solutions for treating waste, but with little effort to prevent waste production. In the ‘receptive’ stage, the early 1990s, organizations began to see environmental considerations as a source of competitive advantage. Organizational ‘policy entrepreneurs’ focused company efforts on being more socially responsible. Owing to continuing environmental pressures, the mid-1990s witnessed the ‘constructive’ stage when organizations began to adopt a ‘resource-productivity framework to maximize benefits attained from environmental initiatives.’ In this stage, companies began to look at product and process design to achieve sustainability objectives.

As firms matured and learned more about Lean, it evolved. The emergence of sustainable value chain initiatives is the emerging evolutionary stage of Lean. Sustainability is an extension of Lean principles. World-class companies, such as Ford, are acting in a proactive manner, creating a new vision for the whole system that includes all organizational personnel as well as value chain suppliers and customers. These firms are using value chain partnerships to look externally in order to apply Lean principles in a sustainable manner to generate increasing economic value. Once consumers signal they are ready to adopt sustainable purchasing behaviors, world-class firms understand they must have sustainable practices already developed and in place.

Although there has been debate on whether synergies exist between profits and sustainable practices, the industry data in the examples cited above illustrate that sustainable practices offer the ability to reduce costs. Non-value-adding activities consume resources and, therefore, over the long run are not economically sustainable. If an activity does not add value, it should be reduced or eliminated if possible. Without waste reduction and elimination, processes and operations are less likely to be sustainable, as resources are typically increasingly scarce.

To date, most Lean initiatives have looked internally and have not had an objective to reduce, lessen, or eliminate ecological impacts. Environmental performance gains or savings are typically not included in an assessment for undertaking Lean improvement activities. These gains or savings are typically not quantified in the financial justification. This is especially true when considering the entire value chain. As world-class firms mature, they begin to understand that Lean practices can be extended externally to the value chain. Consequently, strategic practices utilizing closed-loop value chains to achieve both waste elimination and enhanced environmental performance are beginning to emerge. These points demonstrate that sustainability is the current frontier of Lean.

Lean and sustainability promote the ability to reduce resource or capacity requirements through conservation and reclamation activities and the ability to capture resources for a cost that is less than the value recovered. There is no doubt that cost reduction has enhanced bottom line performance through Lean and sustainability initiatives. Also, firms have improved their image through socially beneficial practices.

In the future, Lean and sustainability initiatives must increasingly reflect shared value chain objectives that simultaneously lessen environmental impacts, achieve cost savings, enhance corporate image, and also drive additional revenues. Opportunities exist to simultaneously reduce cost as well as drive additional revenues. For example, some retailers sell canvas shopping bags that are reusable from one shopping trip to another. The sale reduces the expense of plastic and paper bags, while providing a revenue stream of canvas bag sales.

In the future, Lean and sustainable practices must enhance the bottom line from both cost reduction as well as profit generation. Firms must look for opportunities to reclaim or capture resources for a cost that is less than the value recovered as well as drive future revenues. Once firms learn to capture the value of reclaimed products, future revenues will increase, as the cost savings may be passed along to consumers providing a significant competitive advantage and further driving future revenues. Sustainability has emerged as the current Lean frontier as it looks beyond the boundaries of a single transformation process. Now world-class firms must view sustainability over the entire value chain for opportunities to reduce costs as well as drive future revenue streams.