CHAPTER 8

Knowledge Disconnection: The Future of Lean

A noted study of the U.S. food industry estimated that poor coordination among supply chain partners was wasting $30 billion annually.1 This study further noted that supply chains in many other industries suffer from an excess of some products and a shortage of others owing to an inability to predict demand accurately and in a timely fashion. In all likelihood, this is a conservative estimate today, given that supply chains have become more complex and global, which exacerbates the costs of poor supply chain coordination.

Needless to say, the disconnection of knowledge and lack of information sharing between supply chain trading partners represents the economic frontier to extend Lean Management beyond internal initiatives. The exchange of accurate and timely information between supply chain trading partners can lead to significant economic, social, and environmental benefits. This chapter explores the knowledge disconnection concept. It begins with an explanation of the knowledge disconnection idea. Incentives for an early and accurate exchange of knowledge and information are identified. A conceptual framework that is beginning to emerge in some industries is then developed. This framework identifies the technology currently being used that can accomplish a collaborative information sharing process. Historical obstacles for the collaborative exchange of knowledge and information are identified. The chapter concludes with some thoughts regarding the future of knowledge and information sharing.

Knowledge Disconnection Explained

Knowledge management (KM) is an emerging area of commercial and academic research. Presently, it comprises a range of strategies and practices used in an organization to identify, create, represent, and share information. The information comprising the knowledge base of KM systems resides in the lessons learned by individuals and is embedded in organizational processes or practices. This knowledge base should be considered a valuable organizational asset. Similar to other organizational assets, leaders must recognize the importance of investing in the capabilities and the sharing of this asset within their value chain network.

Similar to the process of implementing change referred to in earlier chapters, the knowledge base develops in a phased manner. Initially, the information, insights, and experiences of an internal, localized transformation activity are created. The firm then typically seeks to integrate and coordinate this knowledge across a broader set of activities or systems within the firm. Subsequently, these capabilities are embedded within the processes and practices of the entire firm making them multifunctional and organization based. Eventually, firms that have successfully deployed the knowledge base on a multifunctional scale will seek to have this knowledge base serve as a network-based asset reaching outside the limits of their transformation processes in order to encompass the value chain network.

To date, few companies pursue, contemplate, or even aspire to share timely and accurate knowledge and information with their trading partners. In the future, the ability to predict demand accurately and in a timely fashion, the construction of production schedules capable of meeting demand when demand occurs, and the sharing of internal consumption data with vending partners for timely and accurate replenishment of materials must be an initiative of any world-class Lean organization.

Knowledge Sharing Incentives

It is often a prerequisite for individuals to understand the benefits of change prior to their readiness for adaption emerges. Many forces are driving the competitive need for the early exchange of reliable knowledge and information across a supply chain. First, one of the most compelling reasons today is the more intense nature of global competition. The expansion and access to distribution routes have increased the number of competitors. Similarly, the number of potential customers has grown, as world populations have increased. Global markets present terrific opportunities combined with significant challenges, as potential worldwide customers demand greater product diversity. Second, the increasing pace of knowledge, information, and technology acquisition offers the ability for faster and more cost- effective sharing. Third, supply chains have become much more complex given moves to offshore production. International sourcing for many items has lengthened supply chains and lead times. Longer lead times necessitate supply chain planning visibility. Fourth, the nature of the supply chain cost structure has changed dramatically in recent years. Global markets and more competitors have moved supply chain systems toward universal participation by all supply chain members in an effort to cut costs.2 Fifth, the increasingly innovative nature of products or the shortening length of most product life cycles and the duration of retail trends make it imperative to get products to market quickly. Otherwise, lost revenues or markdown prices will be experienced. For instance, the life cycle of some garments in the apparel industry is 6 months or less. Yet, manufacturers of these garments typically require up-front commitments from retailers that may exceed 6 months making long-term fashion forecasts risky.

These driving forces support the need to respond quickly and accurately to volatile demands and other market signals. An early and accurate exchange of knowledge and information regarding external demands in order to synchronize internal planning and execution will further enable companies to attain the cost savings and productivity benefits cited in many Lean initiatives. Demand visibility provides the potential for numerous, substantial benefits. Benefits attributable to supply chain initiatives utilizing a strategy to synchronize inbound and outbound materials management activities with supply chain partners are well known and documented. Several of these benefits are listed in Table 8.1.

Actual results of several collaborative supply chain pilot knowledge and information exchange initiatives highlight the potential benefits of the collaborative supply chain knowledge sharing framework discussed below. The benefits for retailers include higher sales, higher service levels (in-stock levels), and lower inventories. Manufacturers have experienced similar benefits plus faster cycle times and reduced capacity requirements.3 A Nabisco/Wegman Foods Collaborative Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment (CPFR) pilot study produced a supply chain sales increase of 36–50% through a more efficient deployment of inventory.4 A survey concerning the frequency and the benefits derived from information exchange noted manufacturers citing significant improvements in cycle time and inventory turns, while retailers indicated order response times as short as 6 days for domestic durables and 14 days for nondurables. Four out of ten survey respondents cited at least 10% improvement in both response times and inventory turns. Forty-two percent of survey respondents indicated at least 10% reduction in total inventory in the past 12 months. Forty-five percent of respondents cited reductions of at least 10% in associated costs.5 In supply chain collaboration pilot tests conducted with several vendors, Proctor and Gamble (P&G) experienced cycle time reductions of 12–20%.6 At that time, P&G estimated that greater supply chain collaboration and integration will result in an annual savings of $1.5–2 billion, largely reflecting the reduction in pipeline inventory.7

Table 8.1. Anecdotal Supply Chain Synchronization Benefits

| Downstream customer benefits: |

|

| Upstream vendor benefits: |

|

| Shared supply chain benefits: |

|

In 1996, approximately $700 billion of the $2.3 trillion retail supply chain was in safety stock.8 Supply chain inventory may be as great as $800 billion of safety stock being held by second and third tier suppliers required to provide rapid delivery to their larger customers.9 According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, there is $1 trillion worth of goods in the supply chain at any given time.10 Even a small reduction in supply chain safety stocks is a sizeable dollar figure.

Almost immediately after its initial efforts to collaborate on supply chain forecast development, Heineken's North American distribution operations experienced a 15% reduction in its forecast errors and cut order lead times in half.11 As order lead times are lowered, order response time improves. Anecdotal evidence has noted 15–20% increases in fill rates and half the number of out-of-stock occurrences.12 Enhanced knowledge of future events (e.g., promotions and pricing actions), past events (e.g., weather-related phenomena), internal events (e.g., point-of-sales data and warehouse withdrawals), and a larger skill set gained from collaboration may all contribute to enhance forecast accuracy.13

Supply chain collaboration should also result in lower product obsolescence and deterioration. Riverwood International Corporation, a major producer of paperboard and packaging products has worked to establish collaborative relationships with customers in order to make production scheduling and inventory control less risky.14 This company sought to balance the need to stock up on inventory for sudden demand surges against the fact that paperboard starts to break down after 90 days. With a higher degree of collaboration and a timelier sharing of information between retailer and manufacturer, greater stability and accuracy in production schedules resulted, making inventory planning more accurate. Furthermore, as production schedules more accurately reflected the needs of the retailer to satisfy near-term demand, reductions in manufacturer capacity requirements were possible.

The supply chain synchronization benefits noted in Table 8.1 underscore the importance to share accurate and timely knowledge and information. Initial attempts regarding the development of an exchange framework are emerging. An example framework that could be used to synchronize planning between trading partners is developed below.

A Supply Chain Knowledge and Information Sharing Conceptual Framework

During the past decade, there have been advancements in technology allowing for real-time capture of retail level demand and the exchange of that demand information upstream for a supply chain. If shared, this information offers the dual prospect of greatly reducing excess inventories and enabling supply chain partners to plan production and coordinate purchasing of items needed to meet current demands. Web-based communication is faster and is available at a price more trading partners can afford. It is well known that older communication techniques are slower, typically require a more error-prone manual entering of identical data by both trading partners, may be unaffordable by some supply chain trading partners, and may be done in batch file transfer mode, which further delays the exchange of information.

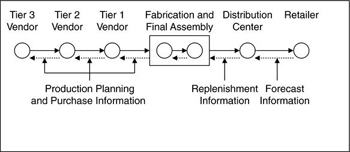

Current technologies offer supply chain partners the ability to develop collaborative plans in a ‘pull’ manner. The knowledge and information exchange should emanate from the point furthest downstream in the supply chain where consumer demand originates, typically the retail level. All other points where demand occurs simply represent purchase orders for inventory replenishment. In most instances, this suggests that a single supply chain forecast is needed and it should originate at the retail level, as depicted in Figure 8.1. Then, working back upstream, demand information may be shared through the supply chain. The process of sharing demand and generating demand forecasts is simply repeated in sequential fashion for each unique pair of upstream trading partners.

Initially, at the retail level, point-of-sale (POS) technology can capture demand as it occurs. Data mining can detect the early onset of demand trends. Then CPFR can be used for communicating demand information, collaborative forecast development, and for developing replenishment plans. These technologies can better enable supply chain partners to share and agree upon joint forecasts and to ultimately synchronize production planning, purchasing, and inventory allocation decisions across a supply chain. These technologies offer an enhanced ability for supply chain trading partners to operate in a Lean manner.

Figure 8.1. Supply chain with retail activities

Note: Solid arrows represent material flows; dashed arrows represent information flows.

Since forecasts or expectations of demand form the basis of all planning activities, collaborative efforts should drive all partner planning activities in a highly coordinated, tightly integrated Lean supply chain. The importance of timely and accurate forecasts cannot be overemphasized, especially for products with long supplier capacity reservation standards such as clothing, trendy items with short life cycles such as toys, low-margin items such as foodstuffs, or longer lead time items produced overseas. For all of these items, time to market is critical. Therefore, timely and accurate forecast information is essential to competitive success.

Collaborative demand forecasts are capable of providing the benefits shown in Table 8.1. Ideally, a collaborative supply chain forecast would accomplish several objectives. It is imperative the approach have characteristics of affordability, accuracy, timeliness, flexibility, and simplicity. First, it should integrate all members of the supply chain. The sharing of selected internal information on a secure, shared web server between trading partners can lower implementation costs and increase accessibility. Second, as depicted in the simplified supply chain in Figure 8.1, the origination point of collaboration should be the demand forecast furthest downstream. This can then be used to synchronize order replenishment, production scheduling, purchase plans, and inventory positioning in a sequential fashion upstream for the entire supply chain. This will promote greater accuracy. Third, a web-based exchange of information can increase speed relative to older existing means of communication. Fourth, flexibility can be enhanced if it is able to incorporate a variety of supply chain structures and company-specific forecast procedures. To accomplish the noted objectives, a five-step framework is outlined below.

Step 1: Creation of a front-end partnership agreement. As a minimum, this agreement should specify objectives (e.g., inventory reductions, lost sale elimination, lower product obsolescence) to be gained through collaboration; resource requirements (e.g., hardware, software, performance metrics) necessary for the collaboration; and expectations of confidentiality concerning the prerequisite trust necessary to share sensitive company information. This trust represents a major implementation obstacle.

Step 2: Joint business planning. Typically, partners identify and coalesce around individual corporate strategies to create partnership strategies; design a joint calendar identifying the sequence of planning activities to follow, which affects product flows; and specify exception criteria for handling planning variances between the trading partners' demand forecasts. Among other things, this calendar must specify the frequency and interval of forecast collaboration. A 1998 pilot study conducted between Wegman Foods and Nabisco to develop weekly collaborative forecasts for 22 Planters Peanut products took approximately 5 months to complete steps 1 and 2.15

Step 3: Development of collaborative forecasts. Forecast development should allow for unique company procedures to be followed affording flexibility. Supply chain trading partners should generate independent forecasts allowing for explicit recognition and inclusion of expert knowledge concerning internal operations and external factors. Given the frequency of forecast generation and the potential for vast numbers of items requiring forecast preparation, simple forecast techniques easily used in conjunction with expert knowledge of promotional, pricing events, or other factors to modify forecast values accordingly could be used. Retailers must play a critical role, as shared POS data permits the development of accurate and timely expectations for both retailers and vendors.

Hierarchical Forecasting (HF) can provide the suggested framework structure for including all supply chain partners in the collaborative pull knowledge and information sharing process. HF has been shown to have the ability to improve forecast accuracy and support improved decision making.16 To date, several studies have offered practical guidelines concerning system parameters and strategic choices, which allow for custom configurations of HF systems within a single firm.17 Furthermore, HF is able to provide decision support information to many users within a single firm, each representing different management levels and organizational functions.18 Consequently, HF is increasingly being commercially offered as an integral framework of the enterprise planning software.

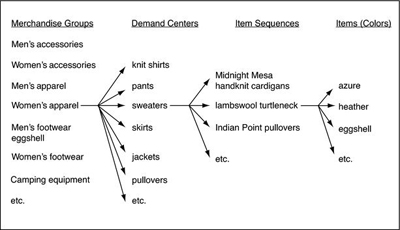

Figure 8.2. Garment retailer product line hierarchical structure

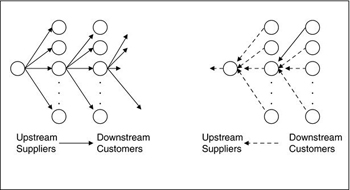

Initial applications of the HF approach have been used to provide forecast information based upon a strategy of grouping items into product families, similar to the example depicted in Figure 8.2 for a garment retailer.19 The firm's typical product line possesses a similar arborescent structure shown in this figure. As depicted in Figure 8.3, the typical supply chain also possesses a tree-like structure with upstream nodes typically supplying inventory to multiple downstream nodes. Therefore, extending HF to an arborescent supply chain structure in order to provide the pull forecast framework is readily done.

Figure 8.3. Example supply chain arborescent structure

Note: Solid arrows represent material flows; dashed arrows represent demand and forecast information flows; all nodes and links not depicted.

The process begins at the furthest point downstream. Consumer demand is captured and demand information is shared upstream between supply chain partners. This process is successively repeated for each echelon comprising any multiechelon supply chain structure. Web-based technology enables real-time posting of supply chain exchange partner's demand values on a secure, shared web server to accomplish the demand aggregation process.

After demand aggregation is performed, demand forecast generation takes place. These forecasts are generated independently by each partner allowing for explicit recognition and inclusion of expert knowledge concerning internal operations and external factors. Since the typical supply chain consists of many echelons, this shared two-step process of demand aggregation and forecast generation is repeated for each echelon in sequential fashion upstream through the supply chain.

Step 4: Sharing forecasts. Each pair of downstream customer and upstream vendor would then electronically post their respective, independently generated forecasts on a dedicated server. At this point, consensus forecasts between trading partners are not likely to exist given the independent forecast development. An exception notice could be issued for any forecast pair where the difference exceeds a preestablished safety margin (e.g., a 5% variance). If the safety margin is exceeded, planners from both firms may collaborate or a rules-based system response could be devised to derive a consensus forecast. If the safety margin is not exceeded, a simple agreed-upon rule could be devised to rectify minimal differences.

Resultant forecasts of this process are then used for synchronized planning. These forecasts would be consistent between upstream and downstream supply chain echelons. It is these forecasts that could be used to eliminate significant value stream waste.

Step 5: Inventory replenishment. Once the corresponding forecasts are in agreement, the order forecast becomes an actual order, which commences the replenishment process. Each of these steps is then repeated iteratively in a continuous cycle, at varying times, by individual products and the calendar of events established between trading partners. For example, trading partners may review the front-end partnership agreement annually, evaluate the joint business plans quarterly, develop forecasts weekly to monthly, and replenish daily.

Collaborative Supply Chain Knowledge and Information Implementation Obstacles

No discussion of a supply chain knowledge sharing framework would be complete without recognition of anticipated barriers to adoption and implementation. As with most initiatives, there will be skepticism and resistance to change. Several of the anticipated obstacles to implementation are noted in Table 8.2 and discussed below.

One of the largest hurdles hindering collaboration is the lack of trust over complete information sharing between supply chain partners.20 The conflicting objective between the profit maximizing vendor and cost minimizing customer gives rise to the adversarial supply chain relationship. Sharing sensitive operating data may enable one trading partner to take advantage of the other. Similarly, there is the potential loss of control as a barrier to implementation. Some companies are rightfully concerned about the idea of placing strategic data such as demand forecasts, financial reports, manufacturing schedules, or inventory values online. Companies open themselves to security breaches.21 However, in a survey of 257 U.S. manufacturing and service companies, only 16% of respondents who were established participants in a business-to-business trading exchange cited security and trust problems.22 Another study found 96% of retailers already sharing information ‘regularly’ with their suppliers, with almost half sharing information with manufacturing partners on a daily basis.23 The front-end partnership agreements, nondisclosure agreements, and limited information access may help overcome these fears. The potential cost savings will also clearly help.

Table 8.2. Expected Barriers to Supply Chain Knowledge and Information Sharing

|

A second hurdle hindering collaboration is a cultural stumbling block. An unprecedented level of internal and external cooperation is required in order to attain the benefits offered by collaboration. Each firm has its own traditional practices and procedures. A survey of senior managers identified that the second biggest barrier to innovation is a lack of coordination.24 If multifunctional internal operations can be synchronized, then it may be possible to pursue collaborative efforts between trading partners.

Similarly, there must be a certain degree of compatibility in the abilities between supply chain trading partners. The availability and cost of technology, the lack of technical expertise, and the lack of integration capabilities of current technology across the supply chain present a third potential barrier to implementation.25 The collaborative process design must integrate skills and procedures that cut across business functions, distribution channels, key customers, and geographic locations.

The necessary ‘bandwidth’ and the associated reliability of technology is the fourth potential barrier. Some companies may not have the supporting network infrastructure. If the necessary trust in the relationship can be developed, synchronizing trading partner business processes with consumer demand need not be overly time consuming nor costly. To make it possible, emerging standards need widespread adoption as opposed to numerous, fragmented standards. Widespread sharing and leveraging of existing knowledge and information across functions within an organization and between enterprises comprising the supply chain may be possible. Common emerging standards will be necessary to promote collaborative supply chain efforts. Attaining a ‘critical mass’ of companies willing to adopt these standards will be important in determining the ultimate success of collaborative practices. The cost of establishing and maintaining collaborative processes without common interfaces will limit the number of relationships each participant is willing to invest in. However, as the ability to collaborate is made easier, the number of supply chain trading partners wanting to collaborate will increase.

A fifth potential obstacle to adoption and implementation concerns two aspects of data aggregation: the number of forecasts and the frequency of forecast generation.26 Bar code scanning technology provides retailers the ability to capture POS data by store, whereas suppliers typically forecast orders at point of shipment such as warehouse. The POS store data is more detailed as it represents daily, shelf-level demands for individual stores. Point of shipment data represents the aggregate of all stores served by one warehouse, typically measured over a longer interval of time, such as a week. In the Wegman Foods/Nabisco pilot study, 22 weekly forecasts for individual products were developed collaboratively. In a full-blown collaboration for store-level planning, the number of daily collaborative forecasts would increase to 1,250 for Planters Peanuts alone.27 It is not uncommon for large retail stores to stock 75,000 or more items, supplied by 2,000–3,000 trading partners.28 This obstacle must be coupled with the vast potential of exception reporting given forecast variances. Given the frequency of forecast variance review and the large number of potential exceptions that may occur, a rule-based approach to automatically resolve trading partner forecast variances will be required. In the development of synchronized plans, these aggregation concerns will need to be resolved. One means to synchronize business processes and overcome these obstacles is reliance upon the HF approach.29

An anticipated sixth obstacle to implementation focuses on the fear of collusion leading to higher prices. It is possible that two or more suppliers, or two or more retailers may conspire and share information harmful to the trading partner. Frequently, this fear arises when the item being purchased is custom-made or possessing a proprietary nature, making it less readily available. Long-term supplier partnerships between mutually trustworthy partners can reduce the potential for collusive activities.

A final potential obstacle to implementation recognizes the important role retailers must play in the process. However, in many industries, the employee turnover rate at the retail level coupled with its consequential impact on the experience and skill sets of retail employees may result in an important barrier to implementation efforts. However, with all initiatives, success encourages adoption. Anecdotal evidence of the potential benefits attributable to collaborative supply chain collaboration will overcome these adoption barriers.

Summary: The Future of Collaborative Supply Chain Knowledge and Information

Many companies have successfully standardized their internal financial and transactional processes. The next step for these companies is engaging supply chain partners using Internet technologies to standardize external financial and transactional processes. Although simplistic, the framework identified above addresses as interenterprise collaborative efforts.

In a survey of 200 information technology executives using or deploying an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, 52% of the respondents indicated current involvement or future plans to create a business supply chain using ERP software.30 The concept is to enable suppliers, partners, distributors, and consumers real-time system access via an extranet. Whether it is managed within an ERP system or it is a stand-alone approach, significant potential is emerging for advanced decision support and enterprise execution systems to focus on integrating and optimizing cross-functional, intraorganizational, and interorganizational planning activities and transactions.

The future evolution of this idealistic framework will permit an automatic transference of supply chain partner knowledge and information into the development of demand forecasts, production schedules, accounting (accounts receivable and payable), human resource requirements, and supply chain planning applications such as the warehousing and inventory control applications. Benefits to be realized for all participants will include the mitigation of the supply chain bull-whip effect through better collaboration, increased sales, lower operational costs, higher customer service levels, and reduced cycle times, among a host of others.