Trading Concessions

The art of negotiating consists of knowing how, why, where, to whom, and when to make concessions.

—Gerald Nierenberg and Henry Calero

Trading concessions are an essential element of the negotiation process. Concessions are made possible when the parties involved have different interests, priorities, and goals. In fact, they play an even greater role in cultures in which negotiating is part of everyday life. In these cultures, negotiators expect to trade concessions back and forth taking whatever time necessary to reach an agreement. As part and parcel of any concession, it is crucial for negotiators to prepare in advance the type of concessions they are willing to trade and concessions they want in return. Reciprocity is a must. Furthermore, after offering a concession, it is important to immediately receive a concession in return as its value loses over time. Trading concessions are the exchange of offers and counteroffers preferably of equal or greater value. Ideally, it is best to trade low-value concessions for higher-priority issues.

The best tactic to trade concessions is to phrase them into conditional or hypothetical questions. For example, a negotiator wishing to make a concession could say, “If I expedite delivery by one week, will your firm absorb the extra costs?” or “What if my firm agrees to modify the product to meet your specifications, will you agree to extend the contract from 1 year to 3 years?” These types of questions invite the other party to enter into exchanging concessions. In case of nonacceptance, both parties can continue negotiating by identifying the reasons for the objection before trading further concessions. For concessions to be traded successfully, negotiators create value by stressing the benefits of their concessions and how it meets the other party’s interests.

Develop a Concession Strategy

Trading concessions demand thorough preparation. During the planning stage, each negotiator develops a list of potential concessions to be traded, their respective priorities, and which issues are negotiable and which ones are not negotiable. These eventual concessions are then ranked by key issues in terms of importance from high to low or classified into three categories: must have, good to have, and trade-offs. By preparing a comprehensive list of potential concessions, the greater the chance of exchanging concessions that satisfy the needs of both parties. In addition, negotiators identify which concessions are wanted in return and how important these concessions are to the other party.

When negotiating in a relationship-oriented culture, it is advisable to plan more concessions than in a deal-oriented culture as haggling is considered a significant part of negotiations. In any culture, it is best to keep in reserve a few concessions that can include both tangible and nontangible benefits in case of last-minute objections. Negotiators adopting a competitive strategy tend to demand major concessions at the start of the discussions at the expense of the other party. This approach fails to optimize the benefits each side can obtain due to a lack of sharing vital information. To overcome this type of behavior, negotiators have to resist giving away concessions by asking information-gathering questions until each party fully understands their respective interests. The development of a clear-cut concession strategy requires two steps: concession identification and information exchange.

Concession Identification

Concession identification involves the following steps:

1. Identifying the concessions to be traded (tangible and nontangible)

2. Estimating the value of concessions and ranking them by priority

3. Establishing which concessions are nonnegotiable

4. Understanding which concessions are wanted from the other party

5. Ranking potential concessions according to musts, good to have, and trade-offs

6. Preparing a few minor concessions to give away if needed to start or restart reciprocity

7. Developing valid arguments/benefits for every concession to enhance its value

8. Keeping a few potential concessions in reserve to overcome last minute objections

To optimize concession trading, it is critical to exchange low-value items for high-value ones. For this to happen, both sides must be willing to share information by adopting cooperative strategies leading to a creative problem-solving situation. By sharing information, each negotiator is in a position to identify the underlying needs of the other party, its goals, the importance given to different issues, and what is nonnegotiable. When a party states that certain items are nonnegotiable, the other negotiator needs to find out whether these items are really nonnegotiable and why or whether it is a ploy to extract further concessions. Once the negotiator understands what the other side is really looking for, its constraints and concerns, concessions can start to be traded. Generally, this problem-solving approach requires that one or both parties think outside the box (expand the pie), thereby creating additional value and options. Besides identifying potential concessions, each party should evaluate their respective value.

Concessions should be classified into hard- (measurable) and soft-value benefits (difficult to measure). For example, hard items include price, cost, delivery dates, penalties, financial terms, quality standards, and so forth. Soft value concessions are subject to different interpretation because of the perception given by the negotiators. For instance, soft-value items include extended warranty, free training, longer contracts, samples, flexible payment terms, trust, reputation, satisfaction, referrals, maintaining the business relationship, the prestige to be associated with the firm, among others. Soft- and hard-value items are also known as tangible and nontangible concessions. In a relationship-oriented culture, nontangible benefits are highly appreciated and play a significant role in reaching agreement. To improve the chances of concluding a deal in a global context, negotiators stress both tangible and nontangible benefits. Concessions considered of a soft nature are very useful in breaking a deadlock, getting the negotiations back on track, or influencing the other party to conclude. The main advantage of these soft concessions is their relative value yet high appreciation by the other party.

By considering both soft and hard concessions, negotiators can shift the discussion away from price issues, particularly in the initial phase. Price is an important and sensitive issue in most negotiations but too often dominates the discussions at the expense of other key elements. For instance, in business-to-business negotiations, when a deal is concluded, professional buyers give priority to nonprice issues by allocating greater weights to financial stability of the firm, its management, performance record, ability to deliver on time, capacity to meet quality standards, cost of production, flexibility to cope with change, and, more recently, management’s adoption of corporate social responsibility standards. In addition to considering nonprice issues, executives negotiating international business deals take a long-term outlook and adopt an implementation mind-set to ensure that the agreement will be doable, profitable, and sustainable.

Information Exhcange

In any negotiation, major concessions are traded after an exchange of relevant information has taken place. It is only after each party understands the underlying needs, priorities and concerns of the other side that important concessions are traded. In the initial stage of the discussions, however, minor concessions are exchanged to encourage negotiators to share information and to create a problem-solving environment. Generally, the most important concessions are made toward the end of the negotiations because of approaching deadlines, nearing the bottom line, or willingness to conclude. By applying the 80/20 Principle, 80% of all major concessions are traded during the 20% remaining time allocated to the negotiations.1 This point is particularly relevant when negotiators from monochronic cultures (where time is considered a rare commodity and not to be wasted) are trading concessions in polychronic environments.

To avoid giving away unnecessary concessions, it is wise to manage the available time efficiently by concentrating on key issues. Whenever possible, negotiators can request additional time, set up another meeting, or postpone the discussions for the time being to avoid making quick decisions under time constraints.

In relationship-oriented cultures, late concessions are highly appreciated by negotiators as it shows how successful they are. In deal-oriented cultures, late concessions are expected especially by professional buyers as it demonstrates their superior negotiating skills, thereby enhancing their career prospects. Too often negotiators concentrate their efforts on the cost of a single item while overlooking the total cost of the overall transaction.

By applying cooperative negotiation strategies, purchasing managers and suppliers can reduce the total cost of a transaction by redesigning a product, changing product specifications, and reducing service or maintenance costs. Generally, this applies to more complex business deals, although it can be useful in everyday negotiations as well. The following example illustrates how two firms were able to overcome a price reduction request by adopting cooperation strategies, exchanging information, and taking a long-term outlook.2

A construction firm purchasing plasterboards for office buildings asked its long-term supplier to reduce its price due to rising competition from foreign firms. The current price of the plasterboards was between $3.80 and $4.15 per board. The construction firm wanted a price reduction to $3.40. After reviewing its cost structure, the supplier requested a meeting with the representatives of the construction firm to discuss the problem as it was unable to meet this price reduction.

Both firms wanted to continue working together, but due to increasing competition from foreign suppliers, the cost of the plasterboards had to be reduced. The supplier suggested to look at the total cost of the boards from the time the boards left its manufacturing plant to their final installation at the construction site. At the moment, the total cost to the construction firm came to $22.50. In other words, the cost of the boards represented only 16.9% of the total cost. This finding is in line with the 80/20 Principle whereby 80% of the cost of any product is made up of 20% of the parts. The additional costs consisted of packing, transporting, handling, and installing the boards at the site.

A review of each stage of the process revealed that 40% of the boards were damaged during installation, required two workers to install them, and incurred high transport costs. In view of these findings, the supplier developed a smaller board (half the size of the current one), which was easier to pack and transport and required only one worker to install it. In addition, it would reduce the number of boards being damaged and the time it takes to install them. The construction firm found this suggestion attractive due to substantial savings. The total costs of the new boards came to $16.25, resulting in a savings of $6.25.

This example shows that through cooperation, information sharing, relying on a creative problem solving approach and an implementation mind-set, both parties obtained greater outcomes by expanding the number of issues under discussions.

Flexibility in Negotiating

After gathering enough information, the negotiator is ready to make an offer or a counteroffer. The counteroffer may mean holding on to the original position or making some concessions. Holding on to the original offer implies a position of firmness, which does not go far and might lead to a breakdown of the negotiations because the negotiator appears to capture most of the bargaining range. The other party may adopt a similar posture and reciprocate with firmness. The parties may become disappointed or disillusioned and withdraw completely.3

The other alternative is to adopt a flexible position, establishing a cooperative rather than a combative relationship.4 This shows there is room for maneuvering and the negotiations continue.

Concessions are an essential part of negotiations. Studies have shown that parties feel better about an agreement if it involves a progression of concessions. Exchanging concessions shows an acknowledgment of the need of the other party and an attempt to reach the position where that need is at least partially met.5 Three aspects of flexibility in negotiation are reciprocity, size, and pattern.

Reciprocity

An important aspect of concession making is reciprocity. If a negotiator offers a concession, he or she expects the other party to yield similar ground. Sometimes a negotiator seeks reciprocity by making his or her concessions conditional. For example, I will do A and B for you if you do X and Y for me.6

Size

The size of concession is also important. In the initial stages, a higher-level concession is feasible, but as a negotiator gets closer to his or her reservation point, he or she tends to make the concession smaller. Suppose a supplier is setting the price of her product with the agent and makes the first offer $100 below the other party’s target price. A concession of $10 would reduce the bargaining by 10%. When negotiations reach within $10 of the other party’s target price, a concession of $1 gives up 10% of the remaining bargaining range. This example shows how the other party might interpret the meaning of concession size.

Pattern

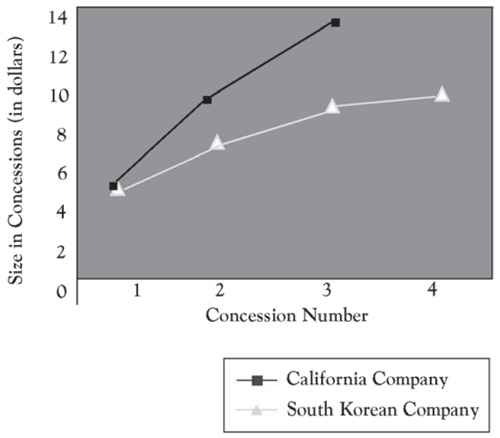

The pattern of concession is significant as well. To illustrate the point, assume a company in California and a company in South Korea are negotiating the unit price of a chemical. Each company is dealing with a difficult customer. As shown in Figure 6.1, the California company makes three concessions, each worth $4 per unit for a total of $12. On the other hand, the South Korean company makes four concessions, worth $4, $3, $2, and $1 per unit for a total of $10. Both companies tell their counterpart they have reached a point where no more concession is feasible. The South Korean company’s claim is more believable because the company communicated through its pattern of concession making that it has nothing more to concede. The California company’s claim, however, is less believable because the company’s pattern (three concessions) implies there is room for additional concession. In reality, though, the California company conceded more than the South Korean company. This example illustrates the importance of the pattern of concessions.7

Figure 6.1. Pattern of concession making for two negotiators.

Source: Based on Lewicki, Saunders, and Minton (2001), p. 72.

Concession Patterns

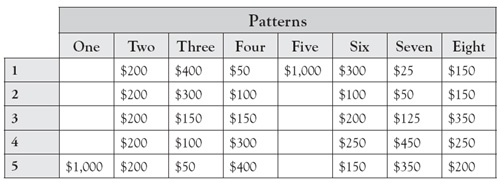

Negotiators have a wide choice of patterns to select from when exchanging concessions. The choice of any one pattern depends on several factors, including the existing relationship between the parties, their preferred negotiating style, the degree of competition, cultural factors, whether it’s one time transaction or repeat business, and so forth. Negotiators can choose up to eight different types of patterns when planning the exchange of concessions. An example describing each pattern consisting of trading one thousand dollars in concessions over five rounds of negotiations is given in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2. An example in choosing a pattern.

Pattern One

Negotiators adopting pattern one refuse to make any concessions until the last minute when a large concession is made. Generally, this approach is likely to lead to a breakdown as the other party will probably walk away from the negotiation. Besides, the other party is not in a position to make counteroffers because of the lack of progress during the first four rounds. Finally, making one large concession toward the deadline may encourage the other party to ask for more concessions. It is best to avoid this pattern by promoting the exchange of information from the beginning to allow each side to start trading minor concessions.

Pattern Two

This pattern is easily recognizable as each concession is of equal value. A variant of this pattern consists of reducing each successive concession by a certain percentage. For example, the first concession is reduced by 10%, by 8% in the second round, by 6% in the third round, and so on. After a few rounds, the other party recognizes the pattern and will keep asking for more concessions knowing in advance what to expect. Less-experienced negotiators may resort to this pattern, but because it is predictable, it is not recommended.

Pattern Three

By making each concession smaller than the previous one, negotiators using this pattern give a clear signal to the other party that the bottom line is getting near. When trading concessions, negotiators should ensure not only that each concession is of lesser value but also that the other party has to work harder and harder to obtain additional concessions. This pattern is by far the most effective as long as negotiators plan carefully the concessions to be traded.

Pattern Four

In this pattern, negotiators keep increasing the value of each concession. It does not take long before the other party realizes what is taking place. This pattern invites the other side to keep asking for more and more concessions. Although some negotiators may like to use this pattern because of their weak bargaining position, pressure from competition or wanting to reach the deal at all cost, this pattern should be avoided.

Pattern Five

Negotiators make only one major concession at the beginning of the discussions and then refuse to make any more concessions for the remainder of the negotiation. This pattern is likely to discourage the other party to keep negotiating as there is no reciprocity eventually leading to an end of the discussions. Negotiators are better off avoiding this pattern as it is not conducive to a win-win outcome. In special situations, this pattern may be used by negotiators under time pressure hoping to reduce the discussions to one round of negotiation or when one party considers itself in a powerful position, thereby imposing its own conditions at the outset without any further discussions.

Pattern Six

Negotiators using pattern six are doing so to either confuse the other party or have no clear concession strategy in mind. It can be an effective strategy; however, the inconvenience outweighs its benefits. For instance, the other party will not know how to reciprocate and may be reluctant to exchange information or make concessions until a clear pattern emerges. Negotiators can adopt this pattern when they are not sure of what they want or are testing the other party’s intentions. This pattern may reflect changing interests, new information becoming available during the discussions, unexpected competition, and so on. In some circumstances, this pattern can lead to a mutually beneficial outcome.

Pattern Seven

Negotiators applying this pattern start by making a few minor concessions to build momentum, as well as encourage reciprocity. The major concessions are then traded during the middle of the discussions followed by smaller concessions toward the end, signaling that its time to bring the negotiations to a close. This pattern is consistent with the 80/20 Principle, whereas 80% of the concessions are made in the remaining 20% of the time left for the negotiations.8 Generally, this pattern together with pattern three are most effective when planning concessions strategy.

Pattern Eight

Negotiators in this pattern start low and then increase the value of concession significantly, beyond their bottom line.

In these situations, negotiators get carried away by the dynamics of the discussions or need to save face, satisfying their egos or wanting to get the contract even at a loss. By keeping a log of the concessions traded, negotiators can have an overview of the status of their position and assess how close they are to the bottom line. There are special instances in which executives accept deals below their bottom line in the hope of recovering the loss in future business, or they have not evaluated their BATNA correctly. Generally, this pattern can lead to renegotiations, onetime only transactions, difficulties in the implementation phase, loss of credibility, and so on. In view of the negative consequences of accepting offers below the bottom line, wise negotiators take time out to review all the concessions traded before making a final offer.

In large-scale negotiations where discussions cover a wide range of issues, it is critical to keep records of the offers, counteroffers, and concessions exchanged. In view of the difficulties of keeping track of the discussions, this task should be assigned to a team member. A log listing which concessions have been made, by whom, under what circumstances, how much time it took from the last concession, and their values is most useful in monitoring progress. It also indicates which party has been more active, who has made more concessions, whether these concessions are of less, equal or greater value, and which remaining issues need to be addressed. This log needs to be reviewed frequently (after a break or at the end of the day) to reorient the negotiation if necessary by changing strategies or tactics. A simplified log for less complex negotiations is equally useful as it allows both parties to assess their relative progress of the discussions. Finally, a review of the concessions traded and obtained can be helpful in detecting a pattern as well as assessing how close each side is approaching their respective bottom line.

An analysis of the recorded information provides an overview of what has been accomplished to date and answers the following questions:

• Who made more concessions?

• Are they of equal or greater value?

• How much time did it take to start exchanging concessions?

• Is there a pattern in the concessions being made?

• How much more ground is needed to conclude?

• What concessions are left before closing?

• What remaining key issues need to be discussed before the deadline?

• Is the bottom line being reached?

Best Practices in Trading Concessions

As the exchange of concessions is at the heart of negotiations, it is vital for negotiators to be aware of the typical mistakes to avoid, objections to overcome, and how to neutralize threats. A list of best practices concerning the exchange of concessions has been developed and grouped into dos and don’ts as given below:

DOs

• Plan concessions in advance.

• Concentrate on the other party’s underlying interests.

• Provide sufficient margins particularly in cultures that are extremely demanding.

• Set aside a few concessions in reserve to be used when concluding the deal.

• Trade small concessions early on to encourage the other party to start sharing information and promote reciprocity.

• Insist on obtaining immediate reciprocity after making a concession (future promises lose value over time).

• Determine the real value of the concessions and what the other party is willing to pay for.

• Remember that 80% of the concessions are traded in the 20% remaining time.

• Have the party work hard in obtaining concessions to be appreciated as well as encouraging the other party to reciprocate generously.

• Provide justification/benefits for each concession to enhance its value.

• Keep a few nontangible concessions, including symbolic ones to break a deadlock or to conclude.

• Observe the other party’s body language to detect hidden motives.

• Take into consideration that negotiators from different cultures concede differently.

• Be aware that how you concede is just as important as what you concede.

• Trade concessions in fewer and fewer amounts requiring the other party to spend more and more time and effort.

• Manage time efficiently by concentrating on key issues.

• Know the competition to resist giving away unnecessary concessions.

• Be aware of false concessions.

• Build trust; otherwise reciprocity is not adhered to.

DON’Ts

• Confuse cost and value.

• Accept concessions too easily.

• Be the first to make concessions on key issues.

• Offer a large concession early in the discussions as it encourages the other party to ask for more.

• Give away important concessions under time pressure.

• Show too much enthusiasm when accepting concessions (winner’s curse).

• Accept future promises in exchange of valuable concessions.

• Assume that the other party values concessions the same way you do.

• Suppose that the other party has similar priorities, needs, goals, and motivation.

• Trade concessions without first creating value.

• Make concessions that affect the bottom line negatively.

• Claim value before creating value.

• Be arrogant when refusing a concession.

• Adopt a concession strategy that can be easily detected by the other party.

• Make quick decisions under time pressure.

• Give away information to the other party without reciprocity.

• Negotiate against yourself.

• Rush into concessions to satisfy the other party.

Summary

Concessions are valuable in closing negotiations. But concessions should not be traded without prior homework. Rushing into concessions without preparation does not create goodwill. Rather it will suggest weakness on your part. A good negotiator clearly identifies the concessions (both tangibles and nontangibles) that can be traded, exchanges information with the other party to understand their needs, priorities, and concerns before trading the concessions.

It is desirable to adopt a flexible position in exchanging concessions since this leads to a cooperative environment. Three essential aspects of flexibility are reciprocity, size of concession, and pattern of offering the concession. The ultimate objective of trading concessions is to create a win-win situation, which opens the door to future business.