Prenegotiations Planning

By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.

—Benjamin Franklin

It is widely recognized that systematic planning and preparation are critical elements of successful business negotiations. Experienced executives devote substantial time to these functions before sitting down at the negotiating table. As a general rule, the more complex the transaction to be negotiated, the longer the planning period. The preparatory phase is also lengthier for international transactions than for domestic ones because of the difficulty of gathering all necessary preliminary information.

The most common business negotiation mistakes, shown in Figure 4.1, reflect insufficient preparation. A majority of these errors can be eliminated or greatly reduced when adequate attention is given to doing background work.

• Unclear objectives

• Inadequate knowledge of the other party’s goals

• Insufficient attention to the other party’s concerns

• Lack of understanding of the other party’s decision-making process

• Nonexistence of a strategy for trading concessions

• Too few alternatives and options prepared beforehand

• Failure to take into account the competition factor

• Unskillful use of negotiation power

• Hasty calculations and decision making

• A poor sense of timing for closing the negotiations

• Poor listening habits

• Too low of an aim

• Failure to create added value

• Insufficient time

• Uncomfortable negotiating

• Overemphasis of the importance of price

Figure 4.1. Most common negotiation errors.

Key Factors

Preparing for negotiations is time consuming, demanding, and often complex. The following factors are considered critical for the prenegotiation phase. Failure to prepare on these points may result in a less-than-satisfactory outcome. A golden rule of negotiations is this: Do not negotiate if you are unprepared. Here is the sequential procedure that a negotiator may follow for prengotiation planning:

• Defining the issues.

• Knowing the other party’s position.

• Knowing the competition.

• Knowing the negotiations limits.

• Developing strategies and tactics.

• Planning the negotiation meeting.

Defining the Issues

The first step in prenegotiation planning is to identify the issues to be discussed. Usually, a negotiation involves one or two major issues (e.g., price, commission, duration of agreement) and a number of minor issues. For example, in the appointment of a distributor in a foreign market, the major issues would be the commission on sales, duration of the agreement, and exclusivity. Other issues could include promotional support provided by the agent, sales training, information flow, and product adaptation. In any negotiation, a complete list of issues can be developed through (a) analysis of the situation at hand, (b) prior experience on a similar situation, (c) research conducted on the situation, and (d) consultation with experts.

After listing all of the issues, the negotiator should prioritize them.1 He or she must determine which issues are most important. Once negotiations begin, parties can easily become overwhelmed with an abundance of information, arguments, offers, counteroffers, trade-offs, and concessions. When a party is not clear in advance about what it wants, it can lose perspective and agree to suboptimal issues. A party must decide what is most important, what is the second most important, and what is least important or group the issues into three categories of high, medium, or low importance. A negotiator should set priorities for both tangible and intangible issues. In addition, the negotiator needs to determine whether the issues are connected or separate. When the issues are separate, they can easily be added later or put aside for the time being. When they are linked to one another, settlement on one involves the others as well. For example, making concessions on one issue is inevitably tied to other issues. After prioritizing the list of issues, a negotiator should touch base with the other party to determine his or her list of issues. The two lists are combined to arrive at a final list of issues that form the agenda. In other words, before the negotiation starts, both sides should firmly agree on the issues they are deliberating.2 There should be no disagreement about the issues to be negotiated.

Each party can develop and prioritize his or her issues and share them with each other. At a prenegotiation meeting or through phone/fax/e-mail communication, the two lists can be combined to develop a common list of issues. This combined list is often called a bargaining list.

Knowing One’s Position

After issue development, the next major step in preparing for business negotiation is to determine one’s goals, a clear understanding of what one is planning to achieve, and an understanding of one’s strengths and weaknesses.

Goals

Goals are usually tangibles, such as price, rate, specific terms, contract language, and fixed package. But they can also be intangible, such as maintaining a certain precedent, defending a principle, or getting an agreement regardless of cost. An intangible goal of an automobile parts manufacturer might be to acquire recognition as a reliable supplier of quality products to major car producers.

Negotiators should clearly define their goals. This requires stating all of the goals they wish to achieve in the negotiation, prioritizing the goals, identifying potential multigoal packages, and evaluating the possible trade-offs among them.

Goals and issues are closely related, and they evolve together, affecting one another. What a negotiator wants to achieve through a negotiation can dramatically affect the issues he or she raises at the negotiation. Likewise, how a negotiator sees an issue has an effect in communicating what he or she wants to achieve from an upcoming negotiation. Goals and issues are interactive; the existence of one quickly produces evidence of the other.

It is important to understand the four aspects of how goals affect negotiation:3

• Wishes are not goals. Wishes may be related to interests or needs that motivate goals themselves. A wish is a fantasy, a hope that something might happen. A goal, however, is a specific, realistic target that a person can plan to realize.

• One party’s goals are permanently linked to the other party’s goals. The linkage between the two parties’ goals defines the issue to be resolved. An exporter’s goal is to give the distributor a low commission on sales, while the distributor’s goal is to settle for the highest commission. Thus, the issue is the rate of commission. Goals that are not linked to one another often lead to conflict.

• Goals have boundaries. Goals have boundaries, set by the ability of the other party to meet them. Thus, if a negotiator’s goals exceed the boundary, he or she must either change the goals or end the negotiation. Stated differently, goals must be realistic, that is, reasonably attainable.

• Effective goals must be concrete and measurable. The less concrete and measurable a person’s goals, the more difficulty the person will have communicating what he or she wants from the other party, understanding what the other party wants, and determining whether an outcome meets the goals of both parties.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Knowing one’s negotiating position also implies an understanding of the company’s strengths and weaknesses. When analyzing strengths, a person should consider those that are real and those that are perceived. For instance, if you are an exporter from a country with an international reputation for producing high-quality goods, you may be perceived as having an advantage over other suppliers. You should identity your firm’s strengths so you can bring them to the forefront when you need them during the negotiations.

A negotiator also needs to identify his or her company’s weaknesses and take corrective measures to improve the deficiencies when possible. The other party is likely to bring the firm’s weak points into the open at a critical moment in the negotiations to obtain maximum concessions. Some weaknesses cannot be eliminated, but others can be reduced or turned into strengths.

Small- and medium-sized exporters often view themselves in a weak position with buyers from larger organizations. If you are negotiating on behalf of a small export firm with limited production capacity, you can turn this perceived weakness into a strength by stressing low overhead costs, flexibility in production runs, minimal delays in switching production lines, and a willingness to accept small orders. Too often, small- and medium-sized firms fail to recognize that many of their perceived weaknesses can become strengths in different business situations.

Small suppliers that are highly committed to their specific transactions are likely to increase their strength with larger buyers. Large companies that deal with smaller ones may be overconfident, thereby coming to the negotiating table poorly prepared. In negotiation, highly committed companies that do their background work prior to the talks improve their chances of achieving desired outcomes.

Knowing the Other Side’s Position

Just as important as knowing what one’s company wants from the forthcoming negotiation is understanding what the other party hopes to obtain. This information is not always available, particularly when the discussions are with a new party. A negotiator may need to make assumptions about the other party’s goals, strengths and weaknesses, strategy, and so on. Whatever assumptions are made, they should be verified during the negotiations. Usually, a negotiator attempts to obtain the following information about the other party: current resources, including financial stability, interests and needs, goals, reputation and negotiation style, alternatives, authority to negotiate, and strategy and tactics.

Current Resources, Interests, and Needs

A negotiator should gather as much information as possible about the other party’s current resources, interests, and needs through research. What kind of facts and figures makes sense depends on what type of negotiation will be conducted and who the other party is. A negotiator can draw useful clues from the history of the other party and from previous negotiations the party might have conducted. In addition, the negotiator might gather financial data about the other party from published sources, trade associations, and research agencies. Interviewing knowledgeable people about the party is another way the negotiator can acquire information. Furthermore, where feasible, a great deal of information can be sought by visiting the other party.4 In addition, the negotiator can explore the following ways to learn the perspectives of the other party: (a) by conducting a preliminary interview or discussion in which the negotiator talks about what the other party wants to achieve in the upcoming negotiation; (b) by anticipating the other party’s interests; (c) by asking others who have negotiated with the other party; and (d) by reading what the other party says about itself in the media.

Goals

After determining the other party’s resources, interests, and needs, the next step for a negotiator is to learn about the party’s goals. It is not easy to pinpoint the other party’s goals with reference to a particular negotiation. The best way for the negotiator to figure out the other party’s goals is to analyze whatever information he or she has gathered about the party, to make appropriate assumptions, and to estimate the goals. After doing this groundwork, the negotiator can contact the other party directly to share as much information about each other’s perspectives as is feasible. Because information about the other party’s goals is so important to the strategy formulation of both parties, professional negotiators are willing to exchange related information or initial proposals days (or even weeks) before the negotiation. The negotiator should use the information gleaned directly from the other party to refine his or her goals.

When identifying the goals of the other party, a negotiator must not assume stereotypical goals. Similarly, the negotiator should not use his or her own values and goals as a guide, assuming the other party wants to pursue similar goals. A negotiator must not judge others by his or her own standards or values.

Reputation and Style

A negotiator wants to deal with a dependable party with whom it is a pleasure to do business. Therefore, he or she must seek information about the reputation and style of the other party. There are three different ways to determine that reputation and style: (a) from one’s own experience, either in the same or a different context; (b) from the experience of other firms that have negotiated with the other party in the past; and (c) from what others, especially business media, have said about the other party.

While past perspectives of the other party provide insight into how it conducts negotiations, provision must be made about management changes that might have taken place, which can affect the forthcoming negotiations. Furthermore, people do change over time. Thus, what they did in the past might not be relevant in the future.

Alternatives

In the prenegotiation process, a negotiator must work out the alternatives. The alternatives offer a viable recourse to pursue if the negotiation fails. Similarly, the negotiator must probe into the other party’s alternatives. When the other party has an equally attractive alternative, it can participate in the negotiation with a great deal of confidence, set high goals, and push hard to realize those goals. On the other hand, when the other party has a weak alternative, it is more dependent on achieving a satisfactory agreement, which might result in the negotiator driving a hard bargain.

Authority

Before beginning to negotiate, a negotiator must learn whether the other party has adequate authority to conclude negotiations with an agreement. If the other party does not have the authority, the negotiator should consider the negotiation as an initial exercise.

A negotiator should be careful not to reveal too much information to someone who does not have the authority to negotiate. The negotiator does not want to give up sensitive information that should have been used only with someone with the authority to negotiate.

A negotiator should plan his or her negotiation strategy, keeping in mind that no final agreement will result. Otherwise, he or she may become frustrated dealing with someone with little or no authority who must check every point with superiors at the head office. The negotiator may, therefore, indicate how far he or she is willing to negotiate with someone without the proper authority.

Strategy and Tactics

A negotiator can find it helpful to gain insights into the other party’s intended negotiation strategy and tactics. The other party will not reveal the strategy outright, but the negotiator can infer it from the information he or she has already gathered. Thus, reputation, style, alternatives, authority, and goals of the other party can indicate his or her strategy.

Information about the other party is helpful in drawing up a negotiating strategy, tactics, and counteroffers. Skill in using positions of strength is an essential aspect of negotiation. Generally, the person with the most strong points leads the negotiation toward its final outcome at the expense of the other party.

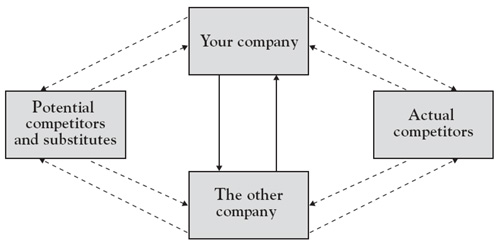

Knowing the Competition

In addition to the previous considerations, it is important to know who the competition will be in a specific transaction. Negotiators often prepare for business discussions without giving much attention to the influence of competition. During business negotiations between two sides, an invisible third party, consisting of one or more competitors, is often present that can influence the outcome. As shown in Figure 4.2, competitors, although invisible, are key players in such discussions.

For example, how many times has a supplier been asked to improve an offer because he or she is told by the other party that competitors can do better? Unless a negotiator plans for such situations in advance and develops ways to overcome them, he or she may find it difficult to achieve the desired outcome in the negotiations.

A negotiator must conduct research about the competition to identify the relative strengths and weaknesses of such third parties for the discussions ahead. A competitor may be able to offer better terms than the negotiator’s company, but because the competitor is currently working to full capacity, it may not be in a position to accept additional orders. Such information, if known, can help a negotiator resist requests to improve his or her offer. When gathering information, the negotiator should address such questions as who the competitors are for this transaction, what his or her company’s strengths are versus the competition, what his or her company’s weaknesses are versus the competition, and how competition can affect his or her company’s goals in this negotiation.

Essentially, knowledge about competitors includes their size, growth, and profitability; the image and positioning of their brands; objectives and commitments; strengths and weaknesses; current and past strategies; cost structure; exit barriers limiting their ability to withdraw; and organization style and culture. The following procedure can be adopted to gather competitive intelligence:5

Figure 4.2. Competitors—the third party in negotiations.

• Recognize key competitors.

• Analyze the performance record of each competitor (i.e., sales growth, market share, profitability).

• Study how satisfied each competitor appears to be with its performance. (If the results of a product are in line with expectations, the competitor will be satisfied. A satisfied competitor is likely to follow its current strategy, while an unsatisfied competitor is likely to come out with a new strategy.)

• Probe each competitor’s marketing strategy (i.e., different moves in the areas of product, price, promotion, and distribution).

• Analyze current and future resources and competencies of each competitor.

Competition has a greater influence in negotiations than the number of concessions, problem-solving discussions, and persuasive arguments. Global competition plays an even greater role in business negotiations than any other factor.

Knowing One’s Negotiation Limits

A crucial part of preparation is setting limits on concessions—the minimum price as a seller and the ceiling price as a buyer. During the prenegotiation phase, each party must decide on the boundaries beyond which there are no longer grounds for negotiation. For example, as a seller, you should know at which point a sale becomes unprofitable, based on a detailed costing of your product and other associated expenses. Similarly, as a buyer, you must determine in advance the maximum price and conditions that are acceptable. The difference between these two points is the zone of possible agreement (ZOPA). Generally, it is within this range that a negotiator and the other party trade concessions and counterproposals.

A negotiator’s opening position as a supplier should, therefore, be somewhere between the lowest price he or she would accept for his or her goods and the highest price he or she perceives to be acceptable by the other party (the buyer). The initial offer must be realistic, credible, and reasonable to encourage the other party to respond. An opening position highly favorable to the negotiator cannot be justified, for example, if it is likely to send a negative message to his or her counterpart, resulting in a lack of trust and possibly more aggressive tactics by the other party.

Target and Reservation Points

A target point refers to a negotiator’s most preferred point, an ideal settlement. The target point should be based on a realistic appraisal of the situation. For example, an exporter wants to pay as little sales commission to an overseas distributor as possible, but that does not mean the distributor is willing to represent the exporter for a meager commission of 1%. Thus, the exporter may set his or her target point for distributor commission at 6%, but not 2%.

A reservation point represents a point at which a negotiator is indifferent between reaching a settlement and walking away from negotiation. The outcome of negotiation depends more on the relationship between parties’ reservation points than on their target points. A method of determining one’s reservation point is to use one’s BATNA, or best alternative to a negotiated agreement.

BATNA

The term BATNA6 refers to the best alternative to a negotiated agreement. Although it appears simple, BATNA has developed into a strong and useful tool for negotiators. This concept was initially introduced by Fisher and Ury while associated with the Harvard Negotiation Project.

BATNA is the standard against which a proposed agreement should be evaluated. It is the only standard that can protect a negotiator from accepting unfavorable terms and from rejecting terms in his or her best interest. Suppose a company in Singapore named SPE is negotiating with an American company called AMC about the purchase of a used four-seater plane. AMC has a standing offer from IND, an Indian company, to buy the plane for $63,000. IND’s offer sets the AMC’s BATNA at $63,000, because AMC will not agree to sell it to SPE for less than $63,000. If SPE believes that it can obtain an equivalent plane for $68,000 from FRC, a French dealer, it will not agree to pay any more than $68,000 to SPE. SPE’s BATNA is therefore $68,000. In this example, there is a settlement range between $63,000 and $68,000, with each party’s BATNA as the outer limit of that range.

In some cases, there is no settlement range because the BATNAs do not overlap. Suppose SPE believes that it can get an equivalent plane for $60,000. It will not agree to pay any more to AMC than its BATNA of $60,000. AMC’s BATNA is $63,000, and there is no settlement range. Cases where no settlement range exists can deadlock a negotiation.

Assessment of BATNA requires the following steps:

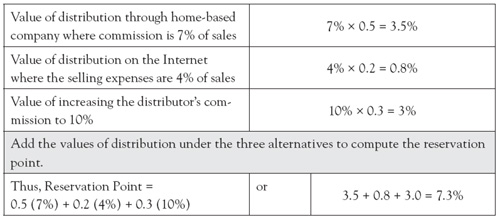

• Brainstorm alternatives. The negotiator should brainstorm to generate alternatives if the overseas distributor refuses to accept 6% commission on sales. The alternatives should be realistic and based on reliable information. For example, the negotiator may consider distributing in an overseas market through a home-based company (e.g., in the United States through an Export Management Company). Another alternative may be to use the Internet to participate in the overseas market. A third alternative may be to increase the commission of the distributor.

• Evaluate each alternative. The negotiator should evaluate each alternative identified previously for its attractiveness or value. If an alternative has an uncertain outcome, such as the amount of sales that can be generated through a home-based company, the negotiator should determine the probability of sales outcome. Consider the following three alternatives:

• Alternative 1: Distributing through a home-based company

• Alternative 2: Distributing on the Internet

• Alternative 3: Increasing the foreign distributor’s commission to 10%

Assume the sales potential in the market is $20 million. The probability of reaching that level under the three alternatives is 0.5, 0.2, and 0.3, respectively. The commission and sales expense vary as follows: Alternative 1, 7%; Alternative 2, 4%; Alternative 3, 10%.

Thus, the expected value of sales is as follows:

• Alternative 1: $20 million × 0.5 = $10 million

• Alternative 2: $20 million × 0.2 = $4 million

• Alternative 3: $20 million × 0.3 = $6 million

Sales commission under the three alternatives will be as follows:

• Alternative 1: 7% of $10 million = $700,000

• Alternative 2: 4% of $4 million = $160,000

• Alternative 3: 1% of $6 million = $600,000

Based on this information, the best alternative among the three options is Alternative 1, and it should be selected to represent the negotiator’s BATNA.

Determining Reservation Point

To determine the reservation point, compute the value of distribution under the three alternatives.

The reservation point (i.e., 7.3%) shows that the negotiator should not give more than 7.3% commission for distribution in the overseas market.

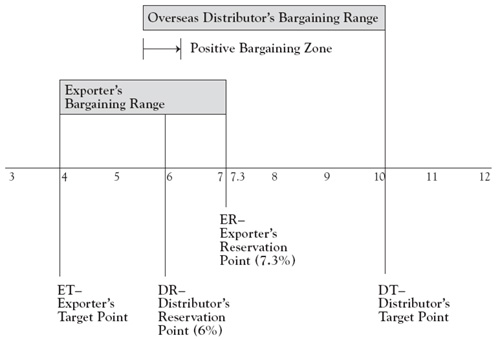

Bargaining Zone

The bargaining zone refers to the region between parties’ reservation points.7 The final settlement, using the previous example, falls somewhere above the commission offered by the exporter and below the commission demanded by the overseas distributor.

The zone of potential agreement (ZOPA) serves a useful purpose because it determines whether an agreement is feasible and whether it is worthwhile to negotiate. To establish the bargaining zone, a negotiator needs not only his or her reservation point but also the reservation point of the other party. Needless to say, determining the other party’s reservation point is not easy. However, based on the available information, the reservation point must be established, even if it is a mere guess.

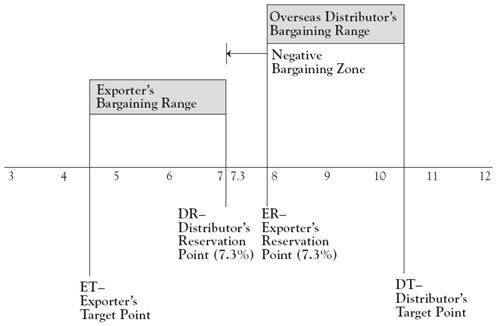

The bargaining point can be positive or negative. In a positive bargaining zone, parties’ reservation points overlap. This means it is possible for the parties to reach an agreement. For example, in Figure 4.3, the exporter’s reservation point is 7.3% and the overseas distributor’s reservation point is 6%. The exporter is willing to pay, at the most, 1.3% more commission. If the two parties reach an agreement, the settlement will be between 6% and 7.3%. If the parties fail to reach an agreement, the outcome is an impasse and is insufficient since both parties are worse off by not coming to some kind of agreement.

The bargaining zone can be negative, where the reservation points of the parties do not overlap, as shown in Figure 4.4. The reservation point of the exporter is 7.3% commission, while the reservation point of the distributor is 8% commission. In other words, the maximum that the exporter is willing to pay as commission does not meet the minimum requirements of the overseas distributor. In this situation, it is advantageous for both parties to give up and call off the negotiation.

Figure 4.3. Positive bargaining zone.

Figure 4.4. Negative bargaining zone.

Power

Power plays a distinctive role in negotiations. Power in negotiations can be of different forms: reward, coercive, legitimate, referent, and expert. Reward power is attributable to a person’s ability to influence the behavior of another person by giving or taking away rewards. Rewards can be tangible (e.g., money) or intangible (e.g., praise and recognition). Coercive power is related to a person’s ability to influence the behavior of another person through punishment. Punishment can be tangible (e.g., a fine) or intangible (e.g., faint praise). Legitimate power refers to a person’s authority to demand obedience (e.g., authority of a senior military officer over a lower-ranking officer). Referent power is based on a person’s respect and admiration of another, which may be related to one’s position, money, or status. Finally, expert power is attributable to a person’s knowledge, skills, or abilities.

With regard to negotiations, no single type of power is more or less effective. However, reward (and punishment) power is less stable because it requires perpetual maintenance. In comparison, status, attraction, and expertise are more intrinsically based forms of power. The ultimate power of a negotiator is to walk out because of having a better alternative.

Developing Strategies and Tactics

A negotiator should prepare strategies based on his or her company’s goals in the forthcoming negotiation, knowledge about the other firm’s goals and position, the presence and strength of competition, and other relevant information. A negotiator has several strategies to choose from, ranging from a competitive to a cooperative stance. The approach he or she selects will probably be a mix of both.

Each negotiation is a separate situation requiring specific strategies and appropriate tactics. For example, in some cases, the negotiator who concedes first is considered to be in a weak position, encouraging the other party to press for more concessions; an early concession in other circumstances is sometimes regarded as a sign of cooperation, inviting reciprocity.

The long-term implications of one’s actions should be taken into consideration when designing strategies and corresponding tactics. For example, if you have been doing business with the same buyer for some years and are generally satisfied with the business relationship, you are likely to adopt a cooperative strategy in negotiations with that buyer. This means both of you are willing to share information, reciprocate concessions, and seek a mutually beneficial result. In contrast, an inexperienced negotiator is generally more interested in short-term gains and often uses more competitive tactics.

Competitive Versus Cooperative Strategies

Negotiating strategies are broadly categorized as competitive and cooperative.8 Competitive strategies are followed when the resources, over which negotiations are to be conducted, are finite. Strategies are developed with the objective of seeking the larger share of the resources.

Competitive strategies require making high initial demands and convey the impression of firmness and inflexibility. Under this strategy, the concessions are made grudgingly and in small quantities. A negotiator using a competitive strategy likes to convince the other party that he or she cannot accommodate anymore, and if an agreement is to be reached, the latter must concede. Competitive negotiators speak forcefully, appearing to be making threats and creating a chaotic scenario that intimidates the other party, thereby putting him or her on the defensive.

Competitive strategies are common in circumstances where the negotiation involves a onetime deal and where a future relationship is meaningless. Further, when there is a lack of trust, negotiating parties resort to competitive strategies. Sometimes a negotiator switches to a competitive strategy when the negotiations are not progressing well or when a deadlock occurs.

Overall, competitive strategies do not make sense since they fail to create harmony between the parties and focus on a onetime deal. The emphasis of this strategic posture is a win-lose situation; emphasis is not about enlarging the size of the outcome.

Cooperative (or collaborative) strategies refer to a win-win situation where negotiators attempt to strike a mutually satisfying deal. Cooperative negotiators are willing to work with each other, sharing information and understanding each other’s point of view. The emphasis of cooperative negotiations is on understanding the perspectives of the other party and developing strategies that benefit both. Cooperative strategies lead to creative solutions that enlarge the outcome, whereby both parties get more than what they aspired to initially.

Choice of a Negotiation Strategy

In international business, it is in the interest of both parties to a transaction to consider cooperative strategies that are conducive to the establishment of sound business relationships and in which each side finds it beneficial to contribute to the success of the negotiated deal. A purely cooperative strategy may be impractical, however, when the other side seeks to maximize its own interests, leading to competitive tactics. Therefore, a combination of cooperative and competitive strategies is advisable (with cooperative moves prevailing during most of the discussions and with some competitive moves used to gain a share of the enlarged outcome).

A negotiator must consider alternative competitive strategies in advance, in case the other party interprets a willingness to cooperate as a sign of weakness. Similarly, if the other party becomes unreasonable and switches to more competitive moves to extract extra concessions, the negotiator may need to change his or her negotiating approach.

Other Strategic Aspects of Negotiations

A number of other strategic issues must be determined and analyzed before the negotiations begin. These include setting the initial position, trading concessions, and developing supporting arguments.

Setting the Initial Position

An important issue in any negotiation is to set the initial position. When a negotiator does not know much about the other party, he or she should begin with a more extreme position. Since the final agreements in negotiations are more strongly influenced by initial offers than by subsequent concessions of the other party, particularly when issues under consideration are of uncertain or ambiguous value, it is better to begin with a high position, provided it can be justified. Further, response to an extreme offer gives it some measure of credibility, which can highlight the dimensions of the bargaining zone.

In the context of international business, a negotiator should base his or her decision about initial position in reference to the culture of the other party. In some cultures, negotiators begin with extreme positions, leaving enough room for maneuvering. In Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, bargaining is commonly employed in business deals. Therefore, a negotiator must start with a high position to become fully involved in the bargaining. In most Western societies, negotiators are less inclined to haggle; therefore, a negotiator should set the initial position close to the terms he or she is willing to accept.

Trading Concessions

A business negotiator must plan in advance which concessions to trade, if necessary; calculate their cost; and decide how and when to trade them. Successful executives consider the timing and the manner in which they trade concessions just as important as the value of the concessions. For instance, a small concession can be presented in such a way that the other party believes it is a major gain. When the other party sees that worthwhile concessions are being traded, he or she becomes more cooperative and reciprocates with better offers too.

The consequences of concessions are important in international business negotiations. For instance, in some cultures, negotiators trade small or no concessions in the early stage of the session and wait until the end to trade major trade offers. In other cultures, frequent concessions are presented in the opening phase, with fewer trade-offs offered in the closing period. For this reason, a negotiator must plan in advance a few inexpensive, yet high-value, concessions for emergency purposes, in case further offers are expected or necessary to close the deal. Last-minute concessions are anticipated by many negotiators when a transaction is nearing completion. In fact, in some countries, this practice is interpreted as a sign of cooperation and a willingness to find a mutually agreeable outcome.

The identification of concessions is, therefore, a critical element in negotiation preparation. In addition to determining which concessions are relevant for the negotiations, a negotiator must also estimate their value, establish their order of importance, determine what is expected in exchange, and plan when and how to offer them.

Developing Supporting Arguments

An important aspect of conducting successful negotiations is the ability to argue in favor of one’s position, duly supported by facts and figures, and to refute the points made by the other party through counterarguments. This requires prior preparation by analyzing collected information from various sources. In this process, seeking answers to the following questions can help:

• What kind of factual information would support and substantiate the argument?

• Whose help might be sought to clarify the facts and elaborate on them?

• What kind of records, databases, and files exist in the public domain that might support the argument?

• Has anybody negotiated before on similar issues? What major arguments were successfully used?

• What arguments might the other party make, and how might he or she support them? How can those arguments that go further in addressing both sides’ issues and interests be refuted and advanced?

• How can the facts be presented (e.g., using visual aids, pictures, graphs, charts, and expert testimony) to make them more convincing?

Planning the Negotiation Meeting

A variety of logistical details should be worked out before the negotiations begin so the meeting runs smoothly. These include planning the agenda, choosing the meeting site, setting the schedule, and deciding the order of formal introductions.

Agenda

The agenda of each meeting of the negotiations should be carefully set to decide what topics will be discussed and in what order. When the other party shares his or her agenda, the negotiator should reconcile the two, making sure critical issues are adequately addressed.

Opinions differ about the order in which the issues should be discussed. Some suggest the issues should be taken up according to the difficulty involved in resolving them. Thus, the parties begin with the easiest issue, followed by the next issue (which may be a little more involved), and so on, with the most complex issue coming up last. This way the parties strengthen their confidence in one another so that, by the time a complex issue is examined, they have developed a relationship of harmony and trust. In contrast, many negotiators recommend resolving the most difficult issue first, believing that less important issues will fall in place on their own without the parties needing to expend much effort. According to these negotiators, this method is more efficient than spending time on insignificant issues first.

Further, the parties need to decide whether to tackle one issue at a time or whether to discuss the issues randomly, jumping from one issue to the next. Culturally speaking, Americans prefer the one-issue-at-a-time approach. In other societies, all of the issues are examined together. The Japanese prefer the latter approach. They discuss issues one after the other without settling anything. Toward the end, however, concessions are made to come to mutually agreeable solutions.9 Westerners, particularly North Americans, resent this disorganized approach because they must wait until the end to find out whether an issue has been resolved.10

Meeting Site

Many negotiators believe that the site of the meetings has an effect on the outcome. Therefore, a negotiator should choose a site where he or she might have some leverage. Basically, there are three alternatives to site selection: (a) negotiator’s place, (b) other party’s place, or (c) a third place (i.e., neutral territory).11

The home place gives the negotiator a territorial advantage. Psychologically, the negotiator is more comfortable in familiar surroundings, which boosts his or her confidence in dealing with the visiting party. Furthermore, negotiating at home obviates the need for travel and, thus, saves money. The negotiator is closer to his or her support system, that is, home, family, and colleagues. Any information needed becomes readily available. In addition, playing host to the other party enables the negotiator to enhance the relationship and potentially obligates the other party to be more reasonable.

On the other hand, the home site can put the other party at a disadvantage. He or she is away from home, is probably jet-lagged, and runs the risk of culture shock. All of this is beneficial to the negotiator.

Choosing the other party’s place as the site has merits and demerits as well. A negotiator can see the actual facilities of the other party. Simply being told the party has a large factory may not mean much since concept of size varies from nation to nation. The negotiator can also meet all of the people involved and has the opportunity to assess their connections in the business community and government. Of course, the negotiator must travel to the other party’s site, incur expenses, suffer from jet lag; and negotiate in an unfamiliar environment.

The third alternative is to choose a neutral place. For example, Geneva could be a central site for parties from the United States and Singapore. However, if the other party has been there before and speaks French, the negotiator is no longer negotiating in a neutral place. Negotiators often alternate sites. The first meeting may be held at the negotiator’s place, while the next meeting is scheduled at the other party’s place. This ensures that neither party has a territorial advantage.

A survey of U.S. professional buyers dealing with foreign suppliers showed that 60.5% prefer negotiating in their offices compared with only 6.7% in the supplier’s premises and 17.5% at a neutral site. Of the buyers, 20.9% considered the impact of the negotiation site on the outcome significant; 49.8%, moderate; and 26.9%, slight.12

Schedule

A schedule allocates time to different items on the agenda. The schedule must be realistic and flexible. Enough time must be budgeted for all contingencies. Introductions may take more time than planned. Coffee breaks and lunches do not always coincide with the time allocated. Furthermore, it is difficult to anticipate how many questions each side will raise and how long it will take to answer each question.

In many nations, the tempo is slow and people move at ease. They are not under any time pressure. However, if a negotiator comes from a country where time is money and every minute counts, he or she would be frustrated. A negotiator should not force his or her own values in developing the schedule.

The party that has traveled a long distance from a different time zone needs time to relax. A negotiator should also value the party’s desire to see cultural and historic places. In any event, the schedule must remain flexible so the parties can remain responsive to changing situations.

Introductions

Some societies are very formal; others are not. For example, in the United States and Australia, addressing one another by first names is readily accepted. But overseas, people are often conscious about their status and title. Therefore, they want to be introduced with their appropriate titles. Further, there is the question of protocol, that is, who should be addressed first, next, and last. Making a mistake in identifying someone and mispronouncing a person’s name are social blunders to avoid. It is important to devote attention to all of these minute details.

The following episode shows how a simple error in addressing someone can become an embarrassing situation. Such a situation can be avoided with a little bit of homework.

Sam Perry was the assistant director of a corporate team investigating the prospects of a manufacturing venture in a small Caribbean country. After 6 weeks in the field, the team received a request from the government to address the head of state and his cabinet about their proposal. The team spent several days preparing a presentation. At the last minute, the project director was called away; she assigned Sam to address the assembled leaders in her place.

Sam had spent enough time helping to prepare the presentation that he felt comfortable with it. He even practiced his introduction to the prime minister—the honorable Mr. Tollis—and to the prime minister’s cabinet. Finally, the day arrived for the address. Sam and the team were received at the governmental palace. Once settled into the prime minister’s meeting room, Sam opened the presentation. “Honorable Mr. Tollis,” he began, “and esteemed members of the cabinet…”

Abruptly, the prime minister interrupted Sam. “Won’t you please start over?” he asked with a peeved smile.

Sam was taken aback. He had not expected his hosts to be so formal. They always seemed so casual in their open-necked, short-sleeved shirts, while Sam and his team sweated away in their suits. But Sam soon regained his composure. “Most Honorable Tollis and highly esteemed members of the cabinet,…”

“Be so kind as to begin again,” said the prime minister, now visibly annoyed.

“Most esteemed and honorable Mr. Tollis,…”

“Perhaps you should start yet again.”

Shaken, Sam glanced desperately at his team, then at the government officials surrounding him. The ceiling fans rattled lightly overhead.

One of the cabinet ministers nearby took pity on Sam. Leaning over, the elderly gentleman whispered, “Excuse me, but Mr. Tollis was deposed 6 months ago. You are now addressing the honorable Mr. Herbert.”13

Summary

In any negotiations, the actual interface between the two parties is only one phase of the negotiation process. The most crucial element is the planning and preparatory phase. Yet negotiators, particularly those who are new to the game, often neglect it. Experienced executives know that one can be overprepared but not underprepared. Each party has its own strengths and weaknesses, but the party that is more committed and works harder for its goals achieves the best results. Being prepared is probably the best investment a business executive can make before entering into international negotiations.

Prenegotiation planning requires defining the issues, knowing the other side’s position, knowing the competition, knowing one’s negotiation limits, developing strategies and tactics, and planning the negotiation meeting. Among these factors, one stands out, and that is knowing one’s negotiation limits. This factor deals with determining BATNA, or the best alternative to a negotiated agreement. BATNA is the standard against which any negotiated agreement is evaluated.