Strategies for Small Enterprises Negotiating With Large Firms

Being BIG is no good if your foundation is weak.

—Peter J. Patsula

In recent years, the trend among large firms has been to merge, to form alliances, or to outsource to remain competitive in the global marketplace. Large firms, by contracting out value-added activities to smaller outside suppliers, create greater contacts between large and small enterprises. Because of their size and resources, larger firms tend to obtain more favorable agreements in dealing with smaller ones. Experience shows, however, that negotiators from smaller enterprises, when entering discussions, can improve their outcomes not only by being well prepared but also by being prepared to walk away from potentially unprofitable deals. One of the major weaknesses of smaller firms is to allow the bigger party the control of the negotiating process in the faint hope of getting sizable contracts.

Larger companies, being well aware of this, encourage smaller firms in the illusion of securing substantially lucrative future business by making them accept major and immediate concessions in current deals. Unfortunately, these future orders might not materialize, or if they do, might easily turn out to be unprofitable for the small firm that has been persuaded into giving away too many concessions. In the long term, these small companies may go out of business because of financial insolvency. There are exceptions, however; for example, a small firm to win recognition in the marketplace wishes to associate itself with a world-class leader. In this case, the objective of the negotiation is to reach a deal to claim a well-known firm as its client. Whatever the smaller firms’ objectives, it is important for them to overcome their relatively weak position vis-à-vis the larger party by developing appropriate strategies. This chapter examines strategies that smaller firms may employ to strengthen their bargaining position.

Success Strategies for Smaller Enterprises

Discussed here are strategies that help small businesses in negotiations successfully.

Preparation is the most crucial element in any negotiation: The more complex the deal, the more complex the preparation.1 This is an area where executives from smaller firms have difficulty, mainly because of such factors as having access to few qualified support staff, a lack of information, expertise shortcomings, and, finally, no clear objectives. As a result, when entering into discussions with larger partners, smaller firms find themselves in a weak position right from the start. To compensate for their lack of preparation, they start making unilateral concessions because of at best insufficiently valid arguments to support their proposals. Being prepared means knowing what the other party’s needs are, the risks involved, the type of concessions to be traded (by creating and claiming value), having an alternative plan and knowing their own position vis-à-vis competition.

Another advantage of preparedness is when the more powerful party comes in badly prepared. It is common for large firms to keep their best negotiators for complex business deals, therefore leaving the negotiations with smaller businesses to less experienced junior managers. Sometimes, at the last moment, large firms send in their senior executives without adequate preparation. This reflects large enterprises’ attitude of not taking negotiations seriously with smaller firms.

Being well prepared assumes that you have sufficient time to plan and interact fully with the other party. When negotiators enter into discussions pressurized by limited time, they lose control of the negotiation process, leading to less than optimum decisions. On the other hand, executives with plenty of time use the clock to their advantage by simply displaying patience. This is a typical situation executives from smaller firms find themselves in when negotiating with larger businesses.

A golden rule among professional negotiators is if you do not have time to negotiate, don’t enter into the discussions; otherwise, you run the risk of negotiating against yourself.

To do well in any negotiation, the party that is ready with prepared options and alternatives is likely to do better regardless of their size. The executive walking into a negotiation with multiple options gains bargaining power. For instance, a small firm having several enterprises as potential clients is better placed both to protect its bottom line and to resist making unnecessary concessions. At times, even with limited options, you may find yourself in control of the discussions as long as the other party is unaware of how strong or weak your position is. Frequently, the smaller firm is intimidated by the larger firm and fails to face contentious issues and clarify key elements. This is often due to insufficient technical expertise to master all the essential points in the negotiation. Hiring experts on a short-term basis is an effective way of overcoming whatever deficiencies you may have. The more options you develop, the greater the chances of reaching your goals and protecting your profit margins. One particular danger to avoid is having one major client accounting for the bulk of your revenue. Unless you have a unique product, service, or technology not available anywhere else, this stops you from negotiating effectively.

Find Out How Important the Deal Is to the Large Firm: Determine Your Bargaining Leverage

Before contacting the larger party, the smaller firm must find out how important the deal is to the larger enterprise. The importance of the deal will determine which strategy and tactics the smaller firm needs to develop. According to the 80/20 Principle, 20% of the number of items purchased by a large firm account for about 80% of the total budget.2 The remaining 80% of the items represent only 20% of expenditure. As a result, the smaller firm must find out whether its product or service is marginal or part of the core business of the larger party. Most firms want to deal with core products or services because of the potential size of the business. However, here the terms and conditions for core products are highly demanding and moreover the competition is at its most severe. This calls for detailed preparation that takes a long-term approach to develop a sound business relationship. If, on the other hand, your offer is marginal to the other party and unappealing to others, this can nevertheless present new business opportunities where competition is less fierce.

Associate Yourself With Recognized Organizations: Become a Recognized Player

To increase their negotiating power, smaller firms seek to associate themselves with better known enterprises who already enjoy international status. Furthermore, it is essential in today’s market for smaller firms to obtain certification from recognized standard organizations. For instance, large enterprises that outsource part of their requirements insist on doing business only with firms certified as having ISO 9000. In the case of food products and pharmaceuticals, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration certification is essential because of its international recognition. Similarly, firms obtaining the appropriate European Union standards are allowed to do business in any of the member states. With the enlargement of the European Union to 25 members, smaller firms can now access a greater market potential than ever before. Relying on a world-renowned inspection agency to guarantee that the goods being shipped are in accordance to the pro forma invoice adds bargaining strength. Remember, in most cases, going alone in a negotiation with a larger party is a daunting task unless you are already certified by a recognized world body or already part of a coalition or associating with firms with an international reputation. This can also include dealing with an internationally renowned bank or contracting one’s advertising and transportation to a reputable firm.

Select Large Firms in Difficulty: Get Your Foot in the Door

Probably the most demanding negotiation for a small firm is obtaining the first order from a larger enterprise. Once you are doing business with larger partners, you are taken more seriously in the global marketplace. Although representatives of larger enterprises seek the best deal, they might, when having major difficulties, be more flexible and understanding with new suppliers. For example, when a firm is going through a time of crisis that makes current suppliers nervous about continuing doing business with it, then is the time for a new supplier to begin negotiations with the firm. Moreover, preparations on the part of the large enterprise may be less than adequate because of inside dissensions that hinder the effective management of daily operations. In these circumstances, a small firm could well negotiate a deal that would have been impossible under normal conditions. Even obtaining a modest order places you in a select group of small firms doing business in the big leagues. Size is now no longer a constraint for a smaller firm to negotiate mutually beneficial agreements with larger enterprises.

Identify Individual Units Within the Larger Firm: Build Your Networks

When considering doing business with a larger firm, it is advisable to identify single units within the organization.3 Generally, large corporations can consist of numerous divisions, departments, or separate companies in which they have a controlling interest. As more and more organizations decentralize and give greater decision-making authority to their managers, a smaller firm must identify the right contacts to create a better chance for itself. The aim is for the small firm to negotiate with the people from the larger organization who actually deal with the product. Often, large, successful companies establish small autonomous divisions and units to stimulate individual initiative, internal entrepreneurship, and risk taking.4 In addition, it is important to be sure that these people have decision-making authority. If case decisions are made by committees or by other senior executives, smaller companies can help themselves save time by providing the relevant information that committee members of the larger firm will require to conclude a deal. Another important point for smaller firms is to find out the extent of the other party’s decision-making authority, For example, suppose a smaller firm is negotiating an order worth $1.5 million, but the larger firm’s representative only has the authority to negotiate deals up to $1 million. Any orders, therefore, above that amount must be approved by a committee of senior executives. If the small firm splits the order into smaller amounts that fall within the authority of the representative, the deal can be concluded without having to wait for a committee decision. For example, the smaller firm can propose a trial order worth $300,000 to be followed by two orders of $600,000 each. By doing this you conclude the negotiation with your counterpart without further discussions or delay.

Involve the Real User or Decision Maker in the Discussion: Be a Problem Solver

A typical situation that smaller firms find themselves in when dealing with large parties is that they are likely to negotiate with buyers from the purchasing department. Professional buyers must necessarily seek the best conditions from suppliers. These buyers continually negotiate with large numbers of interested firms and therefore are well informed on what is available and will obtain the best terms. This is accomplished by encouraging suppliers to compete among themselves. Usually, the firm with the lowest price that satisfies the required conditions gets the deal. To be seen as such a successful firm, you need to convince the users within the larger firms of your superior technical capability, higher-quality standards, management commitment, and any other arguments that place your offer above your competitors. Doing so not only gives added value to your firm but also helps to develop an ally on the other side. This person will give direct support to your proposal be convincing his or her buyer to award you the deal. Remember potential users of your product or service are more interested in the technical aspects of your proposal while purchasing executives are mostly concerned with pricing.

Be Ready to Walk: Your Ultimate Power

A source of strength often underrated by smaller firms and frequently misunderstood is walking away from a deal that no longer makes sense. In any negotiations, when a deal begins to look unprofitable, you should seriously consider withdrawing from it. Frequently, small companies are faced with technical and capacity-limiting problems: they might lack qualified staff or plant facilities that can serve larger orders. This limit is based on a thorough calculation of your real potential costs. Having a bottom line coupled with alternatives gives a greater leverage in protecting your interests. Knowing when to walk out of a negotiation gives you greater confidence in advancing the benefits of your proposal as well as being more reluctant to make unnecessary concessions.5 Moreover, the other party will soon realize that this negotiation will be difficult. You now have two separate scenarios: Either the larger firm will consider you as a worthwhile partner, or they might decide to end discussions. If the larger part wants to continue, chances are that you will be closer to achieving your goals, or if the negotiations end early, at least you have saved time on a deal that might have eventually turned risky or gone below expectations. The time and experience gained can be wisely invested in preparing for other negotiations with more cooperative partners.

Readiness to Negotiate Successfully

As already seen, a smaller firm can negotiate more effectively with larger firms by planning negotiations more carefully. Better planning and thorough preparation place a smaller firm in control of the negotiating process, advancing its goals, protecting its interests, and reaching more balanced agreements.

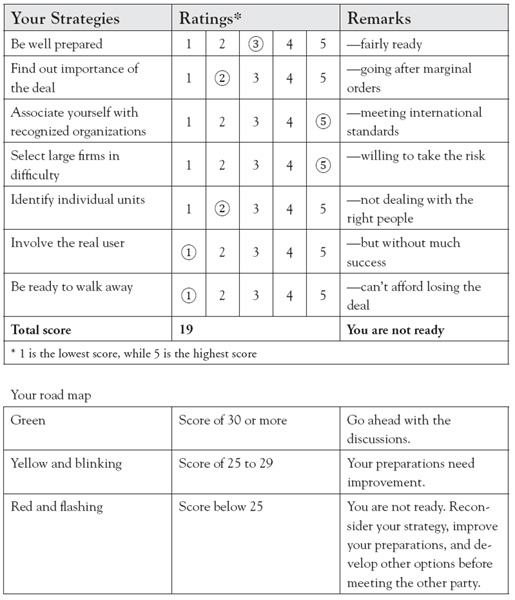

To ensure that you are confident of reaching your goals when entering into your next negotiations, complete the table below to test your readiness. If your score is 30 or more, you are ready. On the other hand, if your score is between 25 and 29, you have certain weaknesses that need to be addressed. A score below 25 indicates serious flaws in your strategies, calling for a postponement of negotiations until you improve your position or select other firms that may be more compatible with your goals.

In this example given in Figure 14.1, the firm with a score of 19 is not ready to conduct a successful negotiation.

Figure 14.1. Testing your readiness to negotiate with larger firms.

Evaluation of Bids

Although price is the main issue in most negotiations, there are times when other factors, such as quality, delivery, financing terms, and so on, are considered more important than price in the buying decision, particularly when evaluating bids. Generally, firms are screened according to the following criteria:

• Relevance of the firm’s core activities

• Reputation

• Previous experience

• Financial stability

• References

• Capacity

• Management’s commitment to social responsibility

• Compliance with national/international quality assurance

Once the bids are received by the due date, the procurement unit prepares a summary of each bid, according to the given weights, and submitted to the implementing unit for review. In general, the procurement unit requires the receipt of three bids before evaluation takes place. Bids are evaluated various ways as each organization has its own set of rules and procedures. As previously stated, bids are generally assessed according to the price and how well their bids meet the technical specifications. If a bid is substantially lower than other bids, it could be that the vendor has misunderstood the requirements or plans to use less expensive inputs that could result in lower-quality products or services. At times, a supplier will submit a very low bid to win the contract but fail to meet the other dimensions.

When submitting a bid, it is vital for the negotiator to know in advance how the bids will be evaluated. Although the lowest price bid is selected, other factors are considered. Besides price, different weights are assigned to various components of the bid. This is particularly valid for more complex projects, consultancies, and large purchases. In general, the evaluation criteria are specified in the solicitation bid request. For instance, procurement officials will assign greater weights to the bidder’s previous experience with similar bids, its reputation, flexibility, capacity, financial stability, competence of the staff, and so on. In complex international projects, the inclusion of local staff or local firms is often considered a key element in assessing bids as it contributes to the building of local competencies and enhances the transfer of know-how.

In case a supplier receives an invitation to bid but is not interested because of other commitments or considers its chances to be rather low, it is recommended that a reply be sent informing the procurement unit that it will not bid on this specific procurement. It is not only good business practice but keeps the firm on the active list of potential suppliers.

At other times, a bid is competitive price-wise, meets all the specifications, and yet it is not retained because the procurement unit has serious doubts about its capacity to deliver on time, its financial stability, or other reservations the unit may have. In these circumstances, the unit can ask the supplier to provide additional information before making its final decision. In the end, the unit sends a report to a higher authority for approval.

More complex or highly specialized bids may be difficult to prepare requiring extra expertise, time, and a better understanding of the requirements. This is the occasion for the negotiator to contact the procurement unit for discussing the technical details of the bid. It is possible that the bid was prepared in a hurry or by staff without the required technical expertise providing an opportunity for the negotiator to recommend changes in the specifications. Ideally, it is better to clarify the technical specifications or standards when the bid is being prepared. The example given next illustrates how bids are evaluated according to weights assigned to key elements of the project.

Example: The Highest Bid Is Selected

A specialized agency involved in trade development received funds to develop an innovative method to assist small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with becoming active players in global markets. The aim was to produce a technical manual for national trade promotion organizations. Technical details for bidding were developed by the procurement unit in consultation with the staff responsible for managing the project. Only companies registered with the agency were invited to submit bids. Because of the specific nature of the project, few companies had the expertise to meet the specific technical requirements.

Upon receipt of the bids, the procurement evaluation panel retained three bids while putting aside several other bids that failed to meet the basic requirements. In addition to the three bids, the panel received e-mails from several other interested firms, but because of other commitments, they could not undertake such a project at this time.

One bidder referred to as B-ONE was a well-known consultancy located in the United Kingdom with previous experience in carrying out similar projects for government agencies. The second bidder (B-TWO) was an Asian consultancy firm with limited experience and technical expertise. The third bidder (B-THREE) was a start-up based in Singapore with excellent technical expertise but no previous experience in carrying projects of this nature.

The three bids were opened and evaluated according to five key criteria and corresponding weights. To carry the project successfully, each bid was evaluated on the basis of know-how and capacity, reputation, meeting technical specifications, financial stability and price. Figure 14.2 summarizes the overall score obtained by each bidder.

Figure 14.2. Evaluating competing bids.

The scores show B-ONE obtaining the highest points (113) while being the most expensive. B-TWO scored 104 because of limited experience and lack of reputation yet being price competitive. B-THREE scored the lowest as a result of its inexperience, financial instability, and lack of an established reputation.

On the basis of this analysis, the evaluation panel selected B-ONE despite its being the most expensive yet within the allocated budget. At the end, the panel members prepared a report to the executive committee explaining in detail why B-ONE was selected.

This example highlights situations in which low-price bidders may not be retained because of other key considerations.

Useful Tips When Bidding

Need to Do

• Follow procedures.

• Possess and display patience.

• Control you emotions.

• Stress public benefits, such as creating jobs/transfer of know-how.

• Build relationship with the decision makers.

• Do not criticize the organization’s rules and personalities.

• Avoid relying on aggressive/unethical behavior.

• Select the right persons to be part of your negotiating team.

• Develop support/alliances to support your bid.

• Be open and flexible in your discussions.

• Be ready to renegotiate contract terms when requested by the procurement unit.

• Refer to past successes, including testimonials, to support your bid.

Need to Know

• The culture and past history of the organization

• The official in charge of procurement

• The personal interests of your counterpart

• Who has authority to negotiate

• Procedures, regulations, and protocols

• The structure of the organization

• The fiscal year, sources of funding, and budgetary constraints

• The potential impediments, restrictions, or problems to the specific bid

• The weights given to each item to be used in the selection/evaluation when submitting bids

• In advance, the bid requirements, timing, and other key issues to influence the standards and criteria for evaluation

Summary

Many small enterprises benefit from the opportunities opened up by larger firms from subcontracting and outsourcing. This can be a lucrative business for the companies involved. Moreover, doing business with larger supply chains can be a highly effective strategy for firms seeking to be more integrated in international trade. But there are many pitfalls for smaller firms, which by definition are likely to be the weaker party in business negotiations. This chapter suggests a series of strategies to strengthen the capacity of small businesses to negotiate more effectively.