CHAPTER 5

Insight in Practice

In The Art of Thought, Graham Wallas presented one of the first models of the creative process. It consists of four steps:

Preparation: where the mind focuses on the problem and explores its dimensions

Incubation: where the problem is internalized into the unconscious mind and nothing appears to be happening externally

Illumination/insight: where the creative idea bursts forth from its preconscious processing into conscious awareness

Verification: where the idea is consciously verified, elaborated, and then applied1

Fresh thoughts and memory thoughts can be found in each of these steps. Fresh and memory thoughts, learning and recall, and intuition and analysis are all employed in various combinations. We take in information and put it onto mental shelves. As new information arrives, our brains search to see whether the information we’ve just taken in is similar to other information already stored on those shelves and, if so, “tags” it as similar. If our brains find a match, the old memories come off the shelf and combine with the new information, resulting in a new thought. Even the most analytical calculation requires judgment and sometimes intuition to recall the appropriate rules, formula, or logic so that it can be applied to the problem at hand. And as we saw with Linus Pauling, in chapter 1, our intuition needs to be fed with material from memory.

More often than not, the pieces and patterns of information are so familiar and come off the shelves so easily that we don’t notice these thought processes occurring. However, when a new pattern is formed by a combination of different pieces in a new way, we experience the result as an insight—the famous “aha!”

While scientists have made significant advances in understanding these phenomena, in this chapter we want to focus not on what the neurons are doing but on how to generate more insights. We can use Wallas’s model as a map for this. While it appears that the steps are to be taken in sequential order, we will see that, in practice, these steps often blend together.

Framing the Problem

You are already thinking about the problem, so you have “framed” it in a certain way. Framing is easy; your mind does it for you automatically. Reframing is what poses the challenge. Frames are pretty sturdy and get sturdier the more they are reused. So, if you want to think about the problem differently, you can really benefit from an outside perspective, ideally from someone with similar experience with Insight Thinking and without much knowledge about the actual problem.

Imagine for a moment that you have a problem that has been around for a while, and you are confident that you have all the relevant information you need to solve it. (This is usually a generous assumption and something we will return to later.) You might think of yourself as working through the following steps with your partner, but don’t get tightly wedded to the steps.

Preparation

Start as you did in the chapter 3 listening exercises, with answering these questions with your partner:

• What is an insight?

• What does your Insight State of Mind feel like?

Once again, this will point your thinking in the right direction—the unknown—and remind you of the most fertile state of mind for insights.

DESIRE

Instead of starting with the problem, begin by describing what you want. What is your desired state of affairs? If the problem ceased to exist, what would the world look like?

These questions begin to flip your perspective and ask what would exist if the problem were no more.

CURRENT REALITY

Using memory thinking, take inventory: What do you know about this problem? What don’t you know about this problem?

Then go on a coached Fresh Thought Hunt (chapter 3). What are some fresh thoughts? What else do you know and not know about this problem?

WHAT’S MISSING?

Have your partner coach you on a Fresh Thought Hunt about what’s missing from your understanding of the current reality.

People often realize in retrospect that one tiny, missed element changed their ability to see a solution. What’s interesting is that the particular piece was always there to be seen; it was just overlooked. So, build out the inventory of your current reality, and see what, if anything, you have missed. Do not bear down hard during this search; maintain an Insight State of Mind.

It’s common for significant insight to occur in the course of these conversations, and it is not unusual for a solution to be discovered. And if not, you have really set the stage for the next step.

Reframing

Go on a Fresh Thought Hunt together focusing on the following questions: How can we look at this problem differently? What’s a new way that we can look at this problem? Describe the problem in as many different, novel ways as you can. Of course, these are classic, creative problem-solving questions. The difference is how we are using them. We are deliberately looking for fresh thoughts and the Insight State of Mind.

You can also try appreciating the problem as it stands: What is good about this issue? Turn your situation into an asset: If this issue is going to persist, then how can you make it a good thing?

For each of these questions, set aside anywhere from five to fifteen minutes—or more if you want. Each will offer different lenses through which to see the world and will disrupt the current thinking. These questions will lead toward higher-quality thought. They shepherd us on the road to a fresh, open state of mind. Eventually, with your new frame of reference, an insight will surface.

Reflection and Incubation

Don’t keep pressing through. Often, you need to get away from the problem for a while. Just working on something else for a bit may help, but occasionally a conversation or meeting should be stopped altogether if it has lost focus and is feeling forced. Breaking away is helpful for some but absolutely crucial for others. If you have the time (or even if you don’t), sleep on it, go for a walk, or switch tasks. This will help let your mind wander while maintaining your equanimity. Focus not so much on the problem but rather on what you really want. What can you do to get where you want to be? What action could you take right now with the means immediately at your disposal?

People frequently describe how, for the longest time, they were asking the wrong questions, and when they finally asked the right question, the solution appeared right in front of them. This reframing of questions is an excellent focus for this preparation conversation.

Insight

Insight isn’t really a separate step. You will likely have had a number of insights during either your preparation or reflection and incubation work. If the solution has not yet occurred to you, return to some of the activities in either of those two steps. Use your good-feeling barometer as a guide in choosing which activities to undertake.

Once you have allowed all your initial work to settle in and given yourself some space to ruminate, it’s time to actively search for some insights. Start by reporting any insights you may have had or anything that may have occurred as a result of the actions that you have taken thus far. Next, go on a Fresh Thought Hunt, as described in chapter 3. Make sure that during this step, you avoid the use of your analytical mind. Speak only when you have a fresh thought, and wait patiently with an open mind until one arrives.

Verification

If you settle on a solution to your problem, be sure to verify it with your analytical mind. By reengaging the analytical mind after producing so many fresh thoughts, you will have all sorts of new material to work with and a completely new perspective from which to approach it.

Reminder: What to Look and Listen For

Of course, by now, you will remember to pay close attention to the feeling of each of these conversations and that the only consistent barometer for an Insight State of Mind is indeed its feeling. Remember also to look for fresh thoughts and insights and avoid thoughts from memory. From time to time, pause, reflect, and perhaps even ask your unconscious mind for a fresh thought, and then wait quietly and see what pops into your head.

Following are a few other items that can serve as points of focus, things to be on the lookout for not only with others but in your personal practice as well.

INCONSISTENCIES IN THOUGHT, MISTAKES, ERRORS,

AND INACCURACIES

It’s common and even desirable to uncover inconsistencies in how you or a colleague is thinking about a particular subject. Sometimes, for example, we find missing pieces or holes in our logic and reasoning. Other times, we may discover contradictions in our interpretation or analysis. You may notice an undifferentiated funny feeling before you can even put something into words. Be sure to explore such feelings.

These inconsistencies and missing pieces are all enormously beneficial because they open up the possibility of new learning and fresh thinking. When uncovered and pointed out by others, a moment of embarrassment or awkwardness almost always arises that we naturally seek to avoid. Regret or disappointment, however, is of no use, and handling such moments adroitly and with compassion can open major doors into insight. This particular skill can be learned, but it does take practice. Catching or being caught in a case of some flawed thinking often provokes defensive feelings and behaviors. While seemingly counterintuitive at first, these moments should be celebrated. You want to move through these embarrassing or defensive feelings as quickly as you can. Luckily, the more you habitually look for the good feeling in your state of mind, the more quickly you will recover when discovering inconsistencies or flaws in your thinking and the less you will engender embarrassment when you happen to spot it in others. You will find that as your resilience in these moments grows, so will the resilience of those around you.

THINGS YOU DON’T KNOW

Park the things you think you know and look for things you don’t. Unanswered questions keep your thinking pointed toward the unknown, where, by definition, you will find insight. Taking stock of what you don’t know, from time to time, allows you to identify these questions and jump off on new paths of exploration.

NEW QUESTIONS OR TOPICS YOU WOULD LIKE

AN INSIGHT INTO

New questions will often occur to you while you are listening. Be sure to make a note of them. Review the facts and ask yourself, “What question hasn’t been asked or demands asking?” Question a particular fact. Is it true, and if so, how can you be sure? What would be a useful topic to have an insight on at this particular time?

ASSUMPTIONS

Occasionally inventory and challenge the basic assumptions you have about the issue. Reflect on what you think is true. If it’s true, how can you be sure? Could it be otherwise?

The above is nowhere near a complete list of what to look and listen for, but it is a good starting point. Be sure you are looking toward that feeling of wonder and curiosity. Of course, these questions and processes are well known. It’s the state of mind that makes them conducive to insight.

Working with Others Is Powerful

Hunting for insights with more than one person is particularly effective. Fresh thought from multiple perspectives can help free us when we have become too familiar with an issue.

EXERCISE:

Working as a Trio

OVERVIEW

One of the most popular exercises we use with our clients involves two people helping a third have insights into a problem or topic of interest. This is not unlike the Insight Listening exercise from chapter 3 with one other person, except that you will have twice the minds on the job and a very different overall dynamic. An illustration can be found on our website, TAOI Online Learning.

Find two people who are interested in helping you have an insight on a particular issue. While preferable, it is not necessary that the participants have knowledge or training in Insight Thinking. You may be surprised to learn that it is generally better if the two people do not know much about the topic that you are bringing to the table.

Begin by describing what an insight is to you and what your Insight State of Mind feels like. All the three participants should engage in this conversation, trying to speak with fresh thoughts and staying in a quiet mind. Don’t describe a moment of insight that you have thought about dozens of times before. Do mention any thought that feels new and fresh.

THE EXERCISE

There are two roles (one speaker and two listeners). Have one of the listeners monitor the time, or set an alarm using a watch or phone.

Part 1

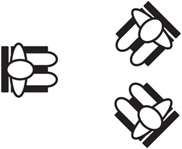

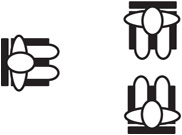

The speaker describes his issue in sixty seconds or less while the other two people listen quietly. They should remain completely silent and refrain from asking any questions. For part 1 of this exercise, the listeners face their chairs toward the speaker, as shown in figure 1.

Part 2

Once the sixty seconds is up or the speaker has finished (whichever comes first), the listeners should swivel their chairs to face each other (preferably with the speaker out of their line of sight) as shown in figure 2.

The listeners in this part should be looking for a good feeling, not barking out the first thought that comes to mind. In fact, the period allotted for sharing fresh thoughts begins in a silence that lasts until a light bulb flashes for one of the participants.

Now, begin to reflect on the topic that was just described. Similar to the two-person exercise from chapter 3, the purpose here is to spend five minutes sharing only fresh thoughts on the subject. Each time either listener has a truly fresh thought on the subject, she shares it with the other listener while being “overheard” by the speaker.

Remember that the purpose is neither to solve the problem nor to give advice, both of which will bring everyone back to memory thinking. It is rather to generate fresh thought around the subject and help facilitate an insight in the speaker. If a memory thought must be spoken to get it out of the way, identify it as you speak it, and then move back into fresh thoughts.

The speaker, throughout this part of the exercise, sits aside. His instinct will be to analyze, correct, or dismiss what the others are saying, but instead, the speaker must remain quiet and look for fresh thoughts and insights, perhaps jotting down on a notepad the thoughts that seem particularly fresh.

The speaker must be careful not to judge the listeners based on their lack of knowledge or experience in the subject. People with a lifetime of relevant experience often have profound insights into their business based on a simple remark from someone in a completely unrelated field of expertise.

Part 3

After the listeners have spent five minutes sharing their fresh thoughts on the subject, the speaker may step back into the mix and comment on the experience.

The speaker should now take two minutes or less to report any new insights that may have occurred during the exercise and comment on what it was like listening to the others discuss the topic using only fresh thinking.

After the speaker has described his experience, the listeners should join the conversation and describe what the experience was like for them. In this last part, everyone should continue to speak only from fresh thoughts and avoid giving advice, and the speaker should talk only around 10 percent of the time. The tendency will be for the speaker to talk as much if not more than the two listeners, but this should be avoided to get the best value from the exercise.

The three parts form one complete round of the trio exercise. If you like, at this point you can switch the role of speaker and repeat the exercise using a new topic.

KEEP IN MIND

This exercise works wonderfully when people follow the structure closely. By offering a very brief description of the problem (perhaps even in thirty seconds instead of sixty) and then stepping aside, the speaker should be able to remove himself from a setting where in most cases he would be inclined to hijack the discussion. When we hear people talking about something that we have a stake in or consider personal, our tendency is to jump in and correct the line of thinking by guiding it back toward the direction we originally had in mind. As soon as we start leading the conversation, listeners are inclined to follow and the result is that everyone gets on the same page, curtailing the likelihood of anything fresh!

Charlie’s Trio Story

Here is an example of an exercise that Charlie recently participated in with a couple of clients.

I had a group of executives participating in this trio exercise, and I decided to join in as the third member of one of the groups. Lately, I had been dealing with a project I had been working on with a number of other people. At the time, it seemed to me that a good number of them were simply not doing their jobs. The result was that I ended up having to step in and pull things together so that everything that needed to get done would get done. I was in a low mood about the whole situation, and it looked like it was going to be hours of more work for me.

I explained this in thirty seconds to my two partners. They turned toward each other, and right away I knew that they got it. They are managers, so they know what it’s like when the people who are supposed to be doing their work aren’t doing it. But almost immediately, they began to get off track and started talking about moving houses and whose job it is to unpack after a move, the husband’s or the wife’s.

I was doing my very best to drop the one thought that was continually coming back into my head: “There’s no relationship whatsoever between their discussion and my problem.” A moment later I thought, “They’re not talking about my problem at all.” I wasn’t getting riled up about the fact that what they were saying wasn’t relevant; in fact, I was in a relatively good state of mind because that was one of the guidelines I had set up, and I wanted to be a quality participant in the exercise. Then I thought, “Whatever they’re talking about, it’s not my problem!” And all of a sudden it hit me like the proverbial ton of bricks: “This isn’t my problem. It’s not my problem; it’s the project leader’s problem. And it’s her job. She’s just not doing it.”

My problem had vanished. All I had to do for it to completely disappear was to write an e-mail that pleasantly said, “These things aren’t getting done, and they are your job, not mine.” It was absolutely magnificent. The issue disappeared even before the e-mail was written—gone in the space of a thought. And of course, the truth of the matter was that I was the one who needed to be reminded even more than my colleagues on the project.

Allison’s Story

Allison Zmuda is an education consultant and friend who describes her experience of this process in her book Breaking Free from Myths about Teaching and Learning.

At a workshop I attended, the facilitators instructed us to engage two other people in a conversation about a problem we cared deeply about and had devoted much time to solving but that still had us stuck. The only rule was that no one was allowed to say anything aloud that they had already thought of before: no familiar anecdotes or analogies, and no repetition of all the reasons why it couldn’t be done. It was the most awkward conversation that I have ever engaged in, but one of the most fascinating. Every time I started to open my mouth, I would close it again, self-censoring according to the rule. After a dozen of these false starts, I began to realize that I had become pretty boring to listen to. Forget about how I came off to family, friends, and colleagues, I had become boring to myself. I had grown comfortable with the notion that any new problem was a familiar problem that I likely either had the answer to or had some authority to speak on and had become increasingly uninterested in the power of context, perception, and new connections. My brain may be designed to look for a memory-based answer to a question, but it also has the capacity for something more.

While developing the capacity to think deeply and create new connections requires practice, the possibility is always there, waiting for you. Simply calling attention to the ability to do so improves the quality of a learning experience. Let’s go back to the conversation with the serious problem and the rule that had rendered me mute.

I found that once I gave up searching for answers to my problem and started listening to the conversation about it, I became engaged not with the dialogue in my head, but with the thoughts shared by these two people. As the content and feeling behind their words penetrated, I began to see new connections, and finally, seven minutes into the conversation, I had something to say. It wasn’t long and it wasn’t pithy, but it had integrity and originality.

The brain can be trained in how to respond to life. When thought settles down and an individual experiences a reprieve from operating in hyper-drive, insights become possible. Some individuals experience this reprieve through running, others through knitting, others through watching tides ebb and flow, but it is possible for anyone to create space that allows for creativity, wisdom, and insight to arrive.2

Insight and Problems

Probably the most common time that we want an insight is when we have a problem and need a solution. Most of us have had an insight that solves a problem, and then our very next thought is about why we didn’t think of it earlier. If you look closely, implicit in this statement is that the solution was there for some time, but you just didn’t see it. Since the solution was available the whole time, your problem wasn’t really the problem. The problem was that you simply couldn’t see the solution.

We have touched on this before, but consider this: where did the problem go after it was solved? Often it dissolves in an instant, and in some cases, you can’t remember what it was, even if you try. How can something that has been present for a week, a month, a year, or ten years be real if it can also just cease to exist? Where did it go? Something that vanishes so completely and so instantaneously can’t have been that (physically) real in the first place.

Alone

So far in this chapter, we have assumed that you have access to someone who can help you open up your thinking. Other approaches that you are familiar with may be equally helpful if they are in the spirit of Insight Thinking and if you avoid advice giving. The key is to get yourself out of an entrenched way of thinking, which can be tricky when you are left to your own mental devices. This is perhaps the main reason why it’s so useful to have others around to assist you on this journey.

If you don’t have anyone to help you or if you prefer working on your own, here are a few ideas that may be helpful. If you generally have insights when you are by yourself, then you probably have your own process for generating fresh ideas, and if it works, you should use it. If that process is stale, however, or if you find yourself alone and in need of some fresh thinking, try some of these tips:

• Change your physical setting. Change your environment, ideally to one that you find encourages a quiet mind. Try going for a walk, taking a nap, or listening to some music.

• Set the problem entirely aside, and instead reflect on this question: What can I do right now to make it more likely that I might have an insight? Ask yourself for a fresh thought about something you could do differently that might open up a new thought. The new thought can be about anything. It will be beneficial even if it doesn’t reference the original problem. Said another way, this technique directs you to look for an insight about having insights but not only about the current problem. If you come up with an answer that feels good, execute it, and then see what happens.

• Use a pen and paper as a stand-in for another person. Note taking with an Insight State of Mind can be a powerful activity. You might even create a written dialogue. This can help objectify your thinking.

![]()

Any conversation and most any problem-solving technique can be enhanced with Insight Thinking. First and foremost, maintain an Insight State of Mind and look for fresh thoughts. When you are working with someone else, don’t get caught up in his or her problem, and don’t offer advice. If you lose the good feeling or if you encounter a spate of thoughts that feel tired or stale, switch gears and look for fresh thoughts and insights. Always remember to verify your insights with critical thinking before acting whenever possible.

Most of our issues in life are products of our thinking and thus completely dissolve with the right insight. As you practice TAOI, you will find that fresh thought, intuition, memory thought, and analysis all work together without your conscious attention, and only when a new pattern is formed in a new way will you experience a substantive aha moment.