RULE #2

Look Only Forward

Now that we’ve pared the number of investment vehicles you should consider by about 99.9%, we’ll reduce them even further, and we’ll delve into how you should use them. If you read only one section of this book, this is it. It will tell you what your winning investment strategy is. This advice applies whether you’re an individual creating her lifetime saving and spending plan, or the administrator of a multi-billion-dollar pension or endowment fund.

First, let’s note how different this will be from the usual investing frenzy that people go through. They’ll often comb through the past history of the thousands—indeed, tens of thousands—of available investment alternatives, or hire a high-paid advisor or consultant to comb through it for them and make recommendations. Then they’ll often choose based mostly on which ones had better returns historically, completely ignoring the perfectly accurate admonition required by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission: past results are no guarantee of future performance. Then once these typical investors have made their choices, they’ll stress constantly about how well their investments are performing, wondering if they should replace them with others.

We won’t do any of that. In fact, we’ll never look back, only forward. Our rules offer a basic foundation that is different from traditional practices. Instead of constantly looking backward at historical performance, our strategy requires investors to envision their future goals and aim toward them.

THE ULTIMATE IN SIMPLICITY—AND SOPHISTICATION

Here is your basic goal, whatever kind of investor you are: you would like to get as much return as you can from your investments, and you would like to be as certain as possible of getting it. These two objectives are at war with each other, because that which is certain is low risk, and that which is low risk is less likely to produce a high return. To put it another way, a guaranteed safety net is more expensive than a shaky net. Therefore, the guaranteed safety net gives you a lower return on your investment than the less expensive shaky net does—if it works out.

You will have to compromise. You will have to decide how much of a guaranteed safety net you can afford—how much you want for certain and are willing to pay for—and how much you can only gamble for. As Rule #1 made clear in the last chapter, all you really need are two investments. One, GIPS, provides the strongest safety net you can possibly get, though at a cost; the other, a world equity fund, provides as much risk as you should prudently take—that is, as much of the risk that is likely to provide a commensurate reward. These are at poles on the risk scale; see Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 The Only Two Investments You Need

Now let’s explore how these two investments can be applied to two related scenarios: one featuring Beth, a reasonably well-off individual investor planning a lifetime saving and spending schedule; and another starring Ralph, an investor who is not well-off but is getting by, and is also making his lifetime financial plan.

LOOKING FORWARD WITH TWO INVESTORS

Beth is the reasonably well-off investor of category 2 that we described in the introduction; Ralph represents the getting-by investor of category 3—not struggling and lacking the finances to invest prudently, but not financially comfortable like Beth, either. Both investors are looking forward to that time when they’ll need to withdraw from or cash in their investments.

Beth: A Well-Off Investor

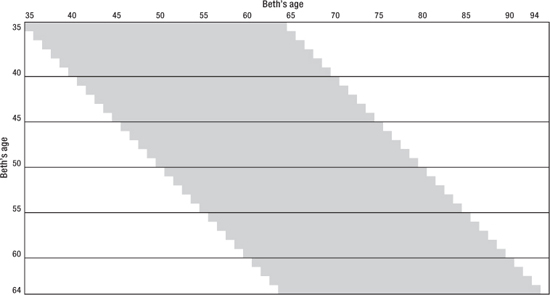

Suppose our reasonably well-off investor Beth has household income of a comfortable $150,000. She starts saving at age 35 and saves the same amount—let’s say $15,000—each year, then retires at 65 and dies at 94. What Beth invests at age 35 (see Figure 2) grows in her investment account to become her retirement income at age 65; what she invests at age 36 grows to become her retirement income at age 66; and so on to ages 64 and 94, respectively. Thus, each dollar resides in Beth’s account 30 years. That’s enough time, according to most stock market experts (based on the history of world stocks that we’ve already presented), to create a high probability that stocks will offer a good return.

But other experts, including Zvi Bodie, a professor of finance at Boston University and author of a leading textbook on investments, point out that there’s still a substantial risk.1 In Japan, for example, stocks fell 80% from their height in 1989. Their prices were still more than 60% below their peak 24 years afterward.

Furthermore, some histories of stock markets have observed that most studies are of the “survivors”—the countries whose stock markets have survived to the present. The obvious 20th-century examples of countries whose stock markets did not survive are Russia and China, where stocks lost all their value after the revolutions of 1917 and 1949. Those losses in Russia and China, however, were already included in the 2013 study of historical world stock returns that we cited in the introduction. Their impact on world stock returns over the period 1900-2012 was a lowering of only 0.34%.2

Still, there’s no guarantee you won’t lose money, possibly quite a lot, in the stock market, especially if you’re not globally diversified. So for a very solid safety net and peace of mind, if you can afford it, you may want to place some of your investments in GIPS. Beth needs to ponder exactly these points and decide how much to put in the safe investment—the GIPS—and how much in the risky one—the world stock ETF. Here on, we’ll assume Beth’s safe investment is specifically U.S. Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS).

Here’s a way she can decide. She can decide how high a safety net she wants and can afford for near-absolute protection against the worst-case scenario. Then she can buy TIPS accordingly and put the remainder in a global stock index ETF. For example, suppose Beth decides she wants an absolute ironclad guarantee, come hell or high water, of at least an additional $22,000 annually from her investments in retirement over and above her Social Security payments. Either she or her advisor calculates that investing half her portfolio, 50%, in TIPS will secure that guarantee.

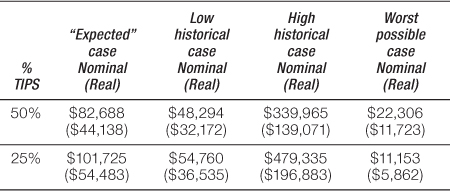

Now look at Table 2, Beth’s annual income after age 65. The entry in the 50% row of the second column—the “Expected” column—shows the nominal and real income from her investments ($82,688 and $44,138, respectively) that Beth can expect after age 65 from her SWS portfolio (Simplify Wall Street—remember?) consisting of 50% TIPS/50% global stock index ETF, if future real returns on world stocks equal their historical averages, and if inflation is what it is expected to be. The entry in the last, “Worst possible case” column in the first row shows what she’ll get in the worst possible case, if world stocks drop by 100% losing all of their value.

TABLE 2 Beth’s Annual Income After Age 65

If Beth decides, on the other hand, that she can afford to use only 25% of her portfolio to ensure maximum security, the results are in the 25% row. This approach gives her better expected income than if she invested 50% in TIPS, but with a lower guaranteed safety net.

The Ups and the Downs of Beth’s Scenario

The scenario we just assumed—the “expected” one—in which Beth gets a real return of 5.0% and a nominal return of 7.2% on her world stock investment, is the one we deem the most likely, given what we know now. But to get an idea of what else can happen, let’s look at the high and low historical 30-year returns shown in the third and fourth columns of Table 2.

In the introduction, we pointed out that over the years 1900-2011, the worst three-decade real return (i.e., the inflation-adjusted type of return, or actual purchasing power) on global stocks—which occurred from 1910 to 1940—was 3.4% and the worst nominal return (i.e., growth in ordinary dollars) was 4.8%. The best 30-year real return was 9.9% and the best nominal return was 13.2%. Table 2 shows what Beth would receive in income with the lowest and highest 30-year historical returns in both the 50% TIPS and 25% TIPS cases. In the best historical scenario, 13.2% nominal return and 9.9% real return, her nominal annual income with 50% TIPS would be $340,000, and with 25% TIPS it would be almost $480,000! (The corresponding real incomes would be $139,000 and $197,000, respectively.)

Why did we single out this last result for an exclamation mark? Only to point out that if you’re tempted to play lottery with the stock market—no matter what the odds—in hopes of securing a life of leisure, the world stock ETF is as good a place to do it as any.

And just in case you’re going to say, “Well, Beth’s no Warren Buffett,” then give her portfolio 60 years of investing, as he has with his, instead of 30, and the same numbers compound to an annual income of $13 million a year with 50% TIPS and $19 million with 25% TIPS!

Notice how simple this is. With the 50% TIPS strategy, all Beth does, each year, is buy about $7,500 of U.S. TIPS and $7,500 of a global stock index ETF. That’s it. That’s all she has to do. She pays almost nothing in fees. She never touches her investments until she retires. She never looks back to see how they’ve done. Then she just makes annual withdrawals.

Not only is this strategy simple, but it will provide Beth with the best return she can possibly get for the risk she takes—bar none.

Why Only the Two Assets?

You might need reminding as to why Beth would opt for only these two investment vehicles. Remember, GIPS and the world stock ETF represent the two poles of risk (Figure 1), so if you combine them in different ratios, you can fall wherever you want on the risk scale. Taking more risk than the global stock ETF by investing in a less diversified portfolio may not be able to assure that your expected return will be better.

But there’s another reason to limit Beth’s portfolio to these two particular assets. Referring back to Table 2, we can understand the reason by asking, Why not increase the GIPS rate with just a little more risk by putting it in corporate bonds with a 1.2% higher rate? The reason is: that really reduces diversification in case of a very, very bad global scenario. If global stocks do terribly over some 30-year period, then that means that global corporations are failing. Hence, many corporate bonds may default. However, government bonds may not be affected, certainly not as much, because most sovereign governments can print money to pay their debts. And if the debts are inflation protected, as GIPS are, then it won’t matter to the investor if that money printing causes inflation.

In other words, the combination of GIPS and world stocks also diversifies you between government and corporate issuers of securities—a type of diversification, especially as a cushion against very bad scenarios, that few people ever mention but that is important.

Ralph: A Getting-by Investor

Now let’s come to Ralph, the getting-by investor. Ralph only earns $50,000 a year and can afford to save no more than $5,000 a year. Nevertheless, he will want to supplement his Social Security payments after he retires.

Ralph can’t afford the TIPS safety net that Beth can afford. He will need to invest all of his savings in the less secure safety net, the world stock portfolio. Let’s suppose he begins investing at age 30 and plans to retire at age 65. Each $5,000 he invests will be invested for 35 years. The last investment, at age 64, will be invested until he is 99, if he lives that long. Thirty-five years should be long enough to weather the ups and downs of the world stock market—at least it was historically. So Ralph stands a pretty good chance of getting the expected return of 5.0%—or at least not too much less, and maybe more—over each 35 years. At 5.0%, his $5,000 will grow to $27,580 a year in real dollars, or $57,000 in nominal/purchasing-power dollars.

Ralph’s portfolio, then, is actually a one-asset portfolio (or two assets if he splits the world stock ETF between a lower-cost U.S. domestic total market ETF and another, total international ETF). He is very likely to be OK, barring a disastrous scenario for the entire world economy, but he will be lacking the comfort and absolute security of Beth’s TIPS safety net.

A Necessary Postscript to Our Scenarios

We could stop talking here, except for two things. First, there’s still a little more to explain about the simple two-asset portfolio, nitpicky little details like tax implications. Furthermore, not every investor’s situation will be as easy to describe as Beth’s or Ralph’s. Not everyone starts investing in the two-asset portfolio early; some investors may be 50 or 60 or 70 years old and already have assets accumulated. The advice to those investors will be a little different, though the basic two-asset portfolio will be the same. And not everyone dies on the dot at 94 like Beth. There’s some risk of dying earlier or later. So we’ll talk about longevity insurance to ensure that you can keep withdrawing from your account as long as you live.

We’ll also talk a little about a few other investments you could make if you wanted to. You don’t really need them because the two we’ve already mentioned—GIPS and a world stock fund—cover the spectrum of risk and return reasonably well. But a few others wouldn’t hurt. You could use them if you really want to tinker.

And, then, of course, there’s probably this other problem: you don’t believe us yet. All of the other financial and investment noise you hear is still ringing in your ears, and it will keep on ringing. It’s an incessant drumbeat that you can’t get away from. You’ll be tempted to believe it. That’s why we’ll have to spend all of Part II telling you why it’s wrong.

We’ve told you how to use the two-asset portfolio in two specific cases, the case of Beth who starts investing at 35, retires at 65, and dies at exactly 94; and the case of Ralph who starts investing at 30 and retires at 65. Now we’ll have to add a small wrinkle or two to the story of Beth. Then we’ll go on to discuss other investors, whose stories may not be quite as neat and clear-cut as Beth’s or Ralph’s.

The Story of Beth Continued: Annuities and Taxes

Let’s add two more considerations to the story of Beth: longevity and taxes.

When we introduced Beth, we assumed she died when she was 94. Of course, that’s a bad assumption for any real person. You don’t know when you’re going to die. If she dies sooner, then she won’t need more from her investments than she planned. But if she dies later, she may not have enough. That’s where those annuities come in. If she’s still alive and kicking at age 94, she’ll need another fund of money to purchase an annuity.

That’s why she should really start investing a little earlier, at age 30 instead of 35, or else put away a little more each year. What she invests between age 30 and 35 will be sufficient to grow to enough money to purchase an annuity that will give her income if she needs it after age 94 for the rest of her life, however long that is.

Taxes are another serious consideration for Beth’s story. In general, taxes are very low with the two-asset portfolio compared to other portfolios. In fact, it would be hard to construct any portfolio with lower taxes. Nevertheless, taxes will have to be paid. Specifically, Beth will have to pay taxes on the capital gains each time she cashes in a portion of the world stock ETF (or the two ETFs that equal global coverage) after her retirement. (Capital gains are profits Beth makes when she sells a stock—simply her sale price minus her original purchase price.) This means her after-tax income will be a little less than the income we quoted earlier.

The world stock portfolio will pay dividends to the investor that also will be taxed. Those dividends can be automatically reinvested, but the tax on them must be paid each year if they’re in a taxable account rather than in a tax-deferred account (e.g., an IRA). The TIPS will also pay a small amount of interest each year on which U.S. federal tax must be paid. (TIPS are exempt from state and local taxes.)

In addition, U.S. federal income tax must be paid each year on any upward adjustment in the TIPS face value. For this reason, if there is a choice whether to hold the TIPS or the world stock ETF in a tax-deferred or taxable account, it’s usually better to put the TIPS in the tax-deferred account.

The dividends and interest paid by the ETFs and TIPS will be more than sufficient to cover these taxes. The amount of the dividends and interest remaining after paying taxes will be reinvested, along with each year’s additional contribution from Beth, in the TIPS or the world stock ETF.

Starting (or Continuing) Later

Not everyone creates their whole life’s saving and spending and investing plan as early as Beth and Ralph. In fact, most people don’t. And even if they do, they may look at their plan and results later as things evolve, and possibly make changes if their goals change.

When we suggested plans for Beth and Ralph, we planned them looking forward, not backward. Our only recourse to past history was that we used the long arc of investment history as a rough guide to what could be expected as a return on global equity investments. That same approach will guide us in making plans for people who start later or who, like Beth and Ralph, made plans early but update them later as time goes on. Before we discuss this further, let’s look at Beth’s plan again. That will help us to discover how we should treat other people’s plans.

Refer back to the picture of Beth’s plan in Figure 2. At each age from 35 to 64, Beth invests $15,000, divided between her two investment vehicles, TIPS and world stock ETFs. Each bar in Figure 2 shows the length of time over which the TIPS she bought in that year mature. All the TIPS she buys are 30-year TIPS. The TIPS she bought at age 35 mature (i.e., pay back their principal) when she is 65, just in time to pay part of her first year’s retirement income. The TIPS she bought at age 36 mature when she is 66, and so on.

The TIPS in Figure 2 look a little bit like a ladder. Well, that’s what they’re called, a “TIPS ladder” (a special case of a bond ladder). At any time, Beth holds in her portfolio a series of TIPS maturing in different years.

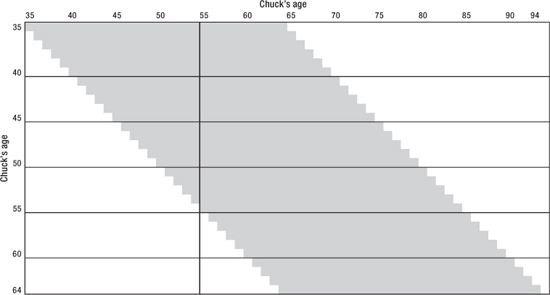

Now consider another well-off investor, Chuck. Unlike Beth, Chuck didn’t start right out using the two-asset portfolio. Let’s suppose he’s 55 years old now and has some money saved. He’ll also be contributing into his portfolio each year in the future. Look at Figure 3: we took Beth’s diagram and drew a straight vertical line through Chuck’s age. If you look at the gray bars to the right of Chuck’s age, you’ll see that at that age, Beth would have had a TIPS ladder consisting of one TIPS maturing in 10 years, one in 11 years, and so on, ending with one maturing in 30 years, the one she just bought.

If he has enough saved to do it, Chuck could buy that exact same TIPS ladder. Then he would be on almost an equal footing with Beth. Whatever is left over he could invest in the world stock ETF, as Beth did. That way, he’ll start out in a similar position on the ladder as Beth.

Well, maybe not quite. If his remaining assets happen to be exactly the same as what he would have had, if he had been investing the same amounts as Beth in the world stock ETF all along, then he would be in exactly the same position on the ladder as Beth. After that, Chuck could invest his contribution each year just as Beth does. Then everything would be the same as Beth.

One more thing: each investment that Beth made in the world stock ETF stayed there for 30 years before she withdrew it. Some of Chuck’s money outside of TIPS will now be invested for less than 30 years; for example, his first retirement withdrawal will occur in only 10 years. Investments in stocks can take wilder swings over shorter time periods than over longer periods. Chuck thus might want to take a little less risk than he would take if he invested it only in the world stock ETF.

Risk/Return Preferences

But why should that be? If Chuck’s portfolio is exactly the same as Beth’s—as if he had been investing like Beth all along—why wouldn’t he continue to do the same thing as Beth? Whether Chuck has exactly the same portfolio as Beth has now or not, what he should do with it depends on his attitude toward risk and return.

For example, we already made a tacit assumption about Beth’s attitude toward risk and return. We assumed that she needed to have a 100% guaranteed safety net at some level (depending on whether she opts for 50% or 25% TIPS). Falling below that safety net was forbidden. But we made no assumption about her attitude toward risk and return beyond that. We just assumed that investing in the world stock ETF would fit it.

We don’t really know if the world stock ETF would exactly fit Beth’s risk/return preferences—sometimes called her “utility function”—and for a good reason. We’ll never know Beth’s utility function.

Behavioral economists sometimes run experiments to determine people’s risk/return preferences. For example, they’ll ask someone, “Would you rather gain $2 or avoid losing $1?” They discover that people’s preferences are internally inconsistent. That is, people will give one response to one question about risk and return, and another to another question, but the responses often logically contradict each other. It’s impossible to find out with any certainty exactly what somebody’s preferences are. So the ideal of calculating exactly what somebody’s portfolio should be based on a precise determination of that person’s risk/return preferences, or utility function, and performing the kind of mathematical optimization that financial economists dream of is exactly that—a dream.

Nevertheless, we can know some things with reasonable certainty; and the theoretical concepts, even if they’re not very practical for most purposes, can help you do that. One of those things we can know with reasonable certainty is that the world stock ETF “dominates” other stock portfolios, in the sense that it has a lower probability of losses and better chance of gains because of its global diversification and lower fees.

There’s pretty good evidence that over a 30-year investment horizon, global stocks also dominate investments in bonds.3 That’s why we didn’t consider putting any bonds in Beth’s portfolio (other than the government-guaranteed TIPS, held to maturity), because we assumed that over a period of 30 years, their probabilities of gains or losses would be dominated by the world stock ETF. For shorter periods, however, such as 5 or 10 years, including low-cost bond index funds in the portfolio may help to contain shorter-term risk.

When Concentration May Be Better Than Diversification

The opposite of diversification of investments is concentration of investments. If, for example, you deliberately decide to hold a portfolio of only 10 individual stocks instead of a global stock ETF, you would be said to be concentrated—you’d hold a concentrated portfolio.

What’s wrong with a concentrated portfolio? Well, in the standard “modern portfolio theory” (MPT) analysis taught in most university investment classes in finance, the more concentrated your portfolio, the more risk you’re taking on that won’t be rewarded with a higher expected return. There’s no point in taking on the risk of concentration if it won’t be rewarded.

But MPT defines risk very simplistically, as how much the market value of the investments fluctuates. This doesn’t always capture what you mean by risk. In fact, if you diversify, it reduces the risk that your return on investment will be low, but it also reduces the risk that it will be high.

Suppose that you actually wanted the risk that your return will be high and you don’t mind the risk that it might be low instead in order to increase the chance of a high return. Then you would have what economists would consider a very unusual—they might even say an irrational—utility function. People are supposed to get more utility—that is, satisfaction—from avoiding downside risk than they gain from an equal amount of upside opportunity. And normally, they do. But what if you’ve already eliminated all the downside risk that you care most about, by investing a portion of your portfolio in TIPS? If you’ve already eliminated the financial risk that really concerns you greatly by creating a strong safety net with some of your money, then you might consider what you have left as “play money.” With this money, you’d rather take a chance on doubling it even if there’s an almost equal chance it will be cut in half. Sure, you could diversify so that the chances would be between adding 10% to your money or losing 10%; but that would be less interesting. So you may want to concentrate, and why not?

We have to realize that “risk” is not always what MPT says it is—in fact, it usually is not.

Back to Beth and Chuck (and Even Ralph)

We’ve just given our rationale for using only the two-asset portfolio for Beth. What about Chuck? Some of his dollars will be invested not for 30 years but for only 10 or 20 years. Over that short a horizon, a bond index ETF will often have a lower probability of losses—based on history and also theory—than the world stock ETF.

Let’s assume Chuck has some bare minimum retirement income requirement, just like Beth. Once he creates a TIPS ladder just like Beth’s (assuming he has enough saved at 55 to do that), he will be guaranteed (by the U.S. government) to meet that requirement. But what should he do with the rest of his investments? What will fit his (purely conceptual) utility function?

There’s no sure way to answer this question. However, we do know one thing: if it’s not simply the world stock ETF all by itself, as it is for Beth, then it is some combination of the 10 investment vehicles we listed in Rule #1. That makes it a lot easier than if we actually had to consider 100,000 investment vehicles. The simple two-asset portfolio we introduced at the beginning (GIPS plus a global stock fund) can probably satisfy most people’s risk and return preferences, and we’ll show you in a moment how Beth and Chuck, and even Ralph, can continue to use it.

However, risk/return preferences—or utility functions—can come in many shapes and forms. There’s no scientific way to match them or even to determine precisely what they are. As long as you stick to the 10 basic low-cost investment vehicles and don’t take too much risk overall—or, for that matter, too little—you can mix and match them in a variety of ways.

Chuck and the Two-Asset Portfolio

Chuck, looking forward into his future, may not want to buy exactly the same TIPS ladder as Beth would have had by age 55. He may have a different amount left over in his portfolio after buying the same TIPS ladder than Beth would have had. This alone might cause him to divide his portfolio differently. Or he may simply perceive a shorter time horizon ahead of him and want to reduce his risk. He may want to increase the TIPS ladder relative to Beth’s, if he can afford the extra safety net.

But what if Chuck can’t afford a safety net? What if he’s more like Ralph than like Beth? Perhaps the assets he’s accumulated are more like what Ralph will accumulate at age 55, and they won’t be enough for him to afford a secure safety net.

The answer is obvious: then the “ladder” he gets on is the same one that Ralph would be on. Ralph didn’t expect to be able to afford a safety net, and unless something unusually and massively good happens, Ralph still won’t be able to afford it. Chuck is in a position as if he had started investing when Ralph started investing—he’s just in the middle of it. So his two-asset portfolio will be the one-asset portfolio, the world stock ETF, just like Ralph’s. And yes, he may be biting his fingernails, just like Ralph. But it’s the best he can do. Chuck will have to take more chances even if he doesn’t confine himself to the two-asset portfolio, no matter what mix of the 10 basic investment vehicles he chooses.

This brings us to another observation about Ralph, but it applies to Beth and Chuck, too. If Ralph’s investments do much better than expected by the time he reaches the age of, say, 55, he may decide he can afford a safety net now—or, if the investor were Beth or perhaps Chuck instead of Ralph, a bigger safety net. In other words, he may decide to “lock in” some of his gains by putting some of his investments in TIPS. This would be a sensible thing to do.

On the other hand, Ralph (or Chuck) may arrive at this age and find that his investments have fared far worse than predicted. In a case like this sad turn of events, he might need to work longer and/or live on less money than he had expected. This struggling-investor strategy may be disappointing if you were nurtured on the 1980s and 1990s notion that everyone will become well-off by investing. But it’s a reality.

SUMMARY OF RULE #2

1. Look only forward to your own future plans and goals. Don’t waste time poring over investments’ historical performance, and don’t waste money hiring someone to do so for you, either.

2. An investor decides how much to put in GIPS and how much to put in a global stock index fund—the only two investments really needed—depending on how high a guaranteed secure safety net she can afford.

3. The mix can be altered over time by projecting forward to see if she can afford to strengthen the safety net.