DEADLY TEMPTATION #5

Use the Strategies That Always Work

There are some things about investing you hear so incessantly that by now everybody just assumes they’re right. The conventional wisdom is so riddled with error that you should question virtually everything you hear. In this Deadly Temptation, we’ll address the following four things you hear that are either wrong or at least not always right:

![]() The first thing you should always do is fund your 401(k) to the max.

The first thing you should always do is fund your 401(k) to the max.

![]() You must be sure to rebalance your investments regularly.

You must be sure to rebalance your investments regularly.

![]() Dollar-cost averaging always wins.

Dollar-cost averaging always wins.

![]() Gold is a hedge against inflation.

Gold is a hedge against inflation.

FUNDING YOUR 401(K) TO THE MAX—OR NOT

What?! Are we going to say it’s wrong to fund your 401(k) to the max? You may find this hard to believe, but yes, that’s what we’re going to say.

Now, it’s not always wrong, but it’s often the wrong thing to do, and it may be wrong more than half the time. So you need to think about it. You shouldn’t do it automatically.

To decide whether you should fund your 401(k) to the max, you need some information. Unfortunately, it may be extremely difficult to get the information you need. You may have to do a lot of demanding to get it, and even then you might not.

Back to Basics: Transferring the Risk from the Employer to the Employee

We need to provide a few basics about 401(k) plans. This discussion applies only to U.S. residents and employees. Other countries have similar plans, but everything could be different.

A 401(k) is provided as a retirement benefit to U.S. employees by their employer. Until the 401(k) plan was invented in 1980, most employee benefit funds were defined-benefit pension plans. That meant the payments employees would get when they retired were determined once and for all, usually as a percentage of their average salary in their last few years of employment. In a pension plan, it was up to the employer to make sure the employees got those payments. Employers had to both put money into the pension fund and hope to get a good return on its investments. If the fund didn’t earn a good enough return on investment, the employer had to put more of its own money into the fund to make up for that.

The 401(k) plan, instead of being a defined-benefit plan, is a defined-contribution plan. Instead of the amount of the future retirement benefit being defined once and for all, the contribution to the fund that both employee and employer make is defined. How much you, the employee, earn later is uncertain. It depends on the return on investment your 401(k) plan earns. This arrangement transferred the investment risk from employer to employee. Employees now bore the risk of not getting as much later as they hoped, if the fund’s returns didn’t turn out well.

Not only did the employer slough off the risk of committing to specific amounts of retirement benefits, but the employer had to contribute less to the fund. The contribution became the employees’ responsibility. Most employers made up partially for the loss of their burden by matching employees’ contributions to their 401(k) plans up to a certain amount.

Now, you’d think employees would be unhappy with suddenly getting stuck with all the investment risk. But remember when the 401(k) was invented. It was right at the dawn of one of the longest bull markets ever. In the 1980s and 1990s, investment returns were spectacular. Employees actually thought they were getting a bad deal with pension funds because they defined way ahead of time what they were going to get in retirement. They didn’t allow the employees to cash in on the great investment returns they heard about constantly. They wanted a piece of those. The 401(k)—where they could invest their own money and reap the high returns—seemed to give it to them.

Well, yes, until it didn’t, of course.

Rules of the Game

Let’s begin by summarizing the surprising result: a lot of the time—for perhaps about half of all 401(k) plans—you should not contribute as much as you can to your 401(k) plan. Let us explain.

Both employer and employee can contribute to the 401(k) plan. The U.S. government allows the employee to deduct the amount of her contribution from her taxable earnings, up to a maximum contribution, which was $17,500 in 2013 and 2014 (or $23,000 if you’re over age 50). This tax advantage is the main reason that financial advisors, and virtually all the advice you’ll hear, recommend that before you make any other investment, you should contribute as much as possible to your 401(k)—the maximum, if you can possibly afford it.

In addition to the employee contribution, the employer often provides a matching contribution. Usually, if the employee contributes nothing, the employer contributes nothing, either. But if the employee contributes $1,000, the employer will match that by contributing a percentage of it to the employee’s plan also. The website 401khelpcenter.com says that 27% of employers match employees’ contributions dollar for dollar up to a specified percentage of the employee’s pay, usually 6%; and 23% of employers match employees’ contributions 50 cents on the dollar up to a percentage of pay.

So if you have a 401(k) plan and your salary is $50,000 and your employer matches your contribution up to 6% of pay, then the maximum the employer will contribute in a year is 6% of $50,000, or $3,000. If your employer matches you dollar for dollar, then if you contribute $3,000 your employer will contribute $3,000. If your employer matches you 50 cents on the dollar, then you need to contribute $6,000 for your employer to contribute $3,000. If your salary is $100,000, your employer will match your contribution up to $6,000 instead of $3,000.

Yes, you should probably contribute to your 401(k) at least up to the point where your employer contributes the maximum. You could still go wrong with that, but it’s a good rule. But should you contribute more than that—up to the maximum that’s tax-deductible? Ninety-nine plus percent of advisors will say, of course you should: it’s tax-deductible! What could possibly be wrong with that advice?

You need to ask, “OK, I get a great tax benefit if I contribute to my 401(k) to the max, but am I giving anything up?” Yes, you could be giving up a lot. You’re giving up fees to the plan’s provider and its investment managers. Some 401(k) plan providers don’t charge too much. If your plan has one of those, then you should contribute to the max. But if the provider is not low-cost, you could be getting ripped off, and it could be for more than you gain from tax deferral.

Unfortunately, you may have a very hard time, with some plans, finding out how much you’re paying. Nobody seems to ask this important question, so even the employee benefits administrator at your company may not know. If you try but just can’t find out the total fees you’re paying, it’s a red flag. It means the plan provider doesn’t want to answer. It’s 99% certain that the fees are too high. If this happens, don’t contribute any more than the amount required to get the maximum employer match.

It may sound crazy, but if you can save more than enough to get the employer match, just pay the tax on the rest. Then skip the 401(k) and invest it in the lowest-cost, best-diversified, or lowest-risk investment available—a total stock market ETF or TIPS, or a combination of the two, as noted in Rule #2. You’ll be better off.

How Much of a Fee Makes It Not Worth It to Contribute?

Suppose you actually are able to find out what your total 401(k) fees are. If you are able to find out, how high can they be before you’ll be better off not to contribute?

Suppose you’re thinking of contributing $10,000 to your 401(k) plan and your tax rate is 20%; but it will be lower after retirement, 15%. Suppose you will withdraw your money in 30 years and your investments will earn 5% until then, of which 2.5% is dividends and income. If the fees in your 401(k) are 1.5%, you will earn 3.5% a year after fees—the 5% return less 1.5% fees.

If you don’t contribute the $10,000 to your 401(k) but take it in salary instead, you’ll have to pay $2,000 tax. That leaves you with only $8,000 to invest. But now you can invest it in low-cost index ETFs with fees of only about 0.2% or less because you don’t have to pay the 401(k) fees. Then here’s the answer:

![]() Invested in your 401(k), you will have $23,858 in 30 years.

Invested in your 401(k), you will have $23,858 in 30 years.

![]() If you pay the tax and then invest outside your 401(k), you will have $27,933 in 30 years.

If you pay the tax and then invest outside your 401(k), you will have $27,933 in 30 years.

![]() Hence, you’ll have $4,075—or 16% more—if you don’t put the money in the 401(k) than if you do.

Hence, you’ll have $4,075—or 16% more—if you don’t put the money in the 401(k) than if you do.

You can do the calculation yourself if you’re adept with spreadsheet arithmetic. You should get a similar result. Our spreadsheet is available at the 3 Rules of Investing website.

Like all such calculations, the results depend on the numbers you put into them—the assumptions. It depends on the tax rates, fees, future return, and the portion of it that is income. But given the assumptions we’ve made in our example, we can calculate that the 401(k) fees would have to come down from 1.5% to 0.95% before it’s worth it for you to contribute to it.

According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), the average total plan cost for small 401(k) plans was 1.46% in 2012.1 Of this, the average expense ratio of the investment vehicles offered by the plans was a high 1.37%. (Note that this does not include transaction costs in the funds—mostly brokerage commissions—which could be as much as an additional half a percent if turnover is high.) Hence, in small plans it will usually not make sense to contribute more than your employer matches. Even in large plans, SHRM says the average cost is 1.03%; so for about half of those it will not make sense to contribute the maximum but only what your employer will match.

SHRM gave only the average costs. In each plan, there may be a low-cost investment alternative. If there is a fund with much lower costs, it may make sense to invest in your 401(k). But the advice that you should “always contribute as much as you can to your 401(k)” is simply wrong.

THE OFF-KILTER ADVICE TO REBALANCE REGULARLY

Now let’s take up the myth of rebalancing. Everybody, but everybody, says you must rebalance your portfolio. The funny thing is, nobody ever really explains why.

In a way, the rebalancing myth is the illegitimate daughter of asset allocation. Asset allocation is something your advisor does when you start out. Let’s keep asset allocation simple: Suppose you start with an allocation of 60% to stocks and 40% to bonds. Your portfolio is $100,000, so you put $60,000 in stocks and $40,000 in bonds. A year passes. It’s a good year for stocks. At the end of it you have $75,000 in stocks and $42,000 in bonds. Your portfolio is now 64.1% stocks and 35.9% bonds. Should you do anything?

Oddly, the financial experts who put so much effort into trying to make the Markowitz optimizer work for asset allocation—and then just fudged the whole thing in the end by plugging in whatever numbers made it work (as we discovered in Deadly Temptation #3)—seem not to have thought about that. They didn’t address at the same time what you would do next, say, a year later. They were too busy optimizing—or trying to.

So what did they do when it dawned on them that you have to decide again later what your asset allocation should be? They just assumed it should be the same as the first time you ran the algorithm. In other words, they decided you needed to “rebalance” to the original allocation. Hence, if your portfolio changes over the year so that it has 64.1% in stocks and 35.9% in bonds, when your original allocation was 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, that means you need to sell some stocks and buy some bonds to get back to the 60/40 mix. But why?

Curiously, this question is never answered. All the academic literature about rebalancing simply assumes you should rebalance—it never, ever explains why. For example, here is a quote from an article titled “Rebalancing” in the Journal of Portfolio Management:2

In general, investors have a target asset allocation that they seek to maintain. When a portfolio’s actual allocation deviates from its target allocation, the result will be tracking error compared to the target allocation. The key benefit of rebalancing is to reduce this tracking error.

The “tracking error” referred to is the error of departing from the 60/40 mix—or whatever allocation was originally decided on. But the article doesn’t explain why allowing the portfolio to depart over time from that mix is an “error,” or what “benefit” reducing this error provides. In fact, it doesn’t even make an effort to explain it; it just declares it. Yet the article is titled “Rebalancing”—you’d think it would say something about why you would do it in the first place. When academicians, for example, are asked to explain what objective is served by rebalancing, they’ll usually say it’s to keep your risk under control—to keep it “constant.” But it doesn’t keep risk under control—in fact, it can destroy your control over that risk.

How Rebalancing Can Destroy Your Control over Your Investment Risk

Here’s an example. One way to control risk is to put a portion of your portfolio into something very safe. Let’s suppose, for example, that you’ve just retired and you’ve done pretty well in your saving and investing: you have a million dollars.

Here is how you perceive risk. Let’s say that on top of your Social Security payments, you feel you must have a bare minimum of $20,000 in income a year, and you must leave at least half a million dollars to your children in 30 years. You refuse to take any risk that might endanger those bare minimum requirements.

Fortunately, you don’t have to. When you retire, lo and behold, there are 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds available that pay 4% interest. If you buy $500,000 of those they’ll pay you $20,000 a year in interest, and you’ll get your $500,000 back in 30 years to leave to your children. These Treasury bonds completely eliminate the risk, except the risk that the U.S. government won’t make good on its guarantee, which you consider negligible. And only half your money—$500,000 out of your $1 million—is needed to secure your minimum requirements. You can invest the other half in something more risky. Therefore, your strategy is to purchase $500,000 worth of U.S. Treasury bonds and take some risk with the other $500,000 by putting it in stocks. Your portfolio now consists of 50% stocks and 50% Treasury bonds.

The first year, the stock market has a bad year and loses 20%. Your stock portfolio goes down in value to $400,000. Meanwhile, you collect the $20,000 interest payment on the bonds, and they’re still worth $500,000.

Now your total portfolio is worth only $900,000. Fortunately, though, you still have the guarantee of at least $20,000 in interest income a year from the bonds and a $500,000 principal payment at the end. Those bonds serve as security against risk, cushioning you against the severe ups and downs that can take place in the stock market.

But your advisor—if you have one—tells you that you must rebalance. Now your stock portfolio is only 44.4% stocks and 55.6% bonds. So you must sell some bonds in order to buy some stocks and restore the 50/50 mix. Perhaps he says you must do this to keep your risk level constant. The thing is, it won’t keep your risk level constant—it will increase your risk. In fact, it will destroy your carefully laid risk avoidance strategy. You will have less Treasury bonds than you bought, so you will no longer be assured $20,000 annual income or a $500,000 principal payment when the bonds mature. You will be more exposed to stock market risk than you were, and more than you wanted to be. Not only that, but if the stock market goes up substantially, you will do much worse with the rebalancing strategy than by holding the Treasuries and the stocks without rebalancing. That’s because you will have more in stocks on average if you don’t rebalance than if you do.

The problem is that the “sophisticated” algorithms of modern portfolio theory don’t think beyond the immediate short-term time period. Hence, they define risk only as how much your portfolio could lose—or could fluctuate—in the very short term. This is like thinking of the risk of flying in a plane as if the risk were only how much the plane might vibrate in turbulence, instead of how likely it is to crash.

Will Rebalancing Increase Your Return on Investment?

Some illustrations suggest you’ll increase your return on investment by rebalancing. This can happen, of course, over certain time periods. But over other time periods—most, in fact—it won’t. There’s no mathematical or theoretical reason that rebalancing should increase your return in the long run or lower your risk. It’s strange that theorists who otherwise expend enormous amounts of effort proving in mathematical detail certain precepts of MPT, expend no effort on advancing a theoretical reason for rebalancing.

Rebalancing is merely an ad hoc device to connect other shaky parts of the MPT structure. The fact that the whole structure is so shaky doesn’t seem to be noticed by either the theorists or the practitioners. Everybody agrees that the structure is sophisticated—so that’s what it is.

In fact, history shows that rebalancing would have performed worse over long time periods than the obvious alternative: buy-and-hold. Rebalancing would have performed poorly compared with not rebalancing—in other words, doing nothing. For example, if a portfolio started out with 50% stocks and 50% bonds in each of the 58 30-year periods from 1926 to 2012, a rebalancing strategy would have beaten buy-and-hold in less than 12% of the 30-year periods, and for only two of those 58 30-year periods—3% of them—by more than 0.2%. The buy-and-hold strategy would have beaten rebalancing by an average of 0.8% per year. (For more information, see the 3 Rules of Investing website.)

The reason is that over long time periods, stocks have tended almost always to outperform bonds. That means that if you don’t rebalance, stocks will gradually become a larger percentage of the portfolio than bonds. But since stocks perform better in the long run, your portfolio will do better if more of it is in stocks. Hence, not rebalancing will outperform rebalancing. This point is easily shown to have been true historically (see the 3 Rules of Investing website for details).

What about performance on a risk-adjusted basis? That’s more difficult to measure; however, the theoretical result—that is, the result derived from MPT itself—would be that risk-adjusted performance will be the same whether you rebalance or not.

But if you don’t rebalance, doesn’t that mean you’ll wind up taking more risk than you intended to? From the example we gave earlier, the answer is obviously not. You should employ a reasoned-through long-run risk avoidance strategy, not the ad hoc strategy of rebalancing.

There’s nothing wrong with rebalancing per se. It’s one strategy you could use. It’s good to have some kind of discipline, and rebalancing could be a candidate. Of course, there’s something seriously wrong with rebalancing if it conflicts with another, perfectly good discipline that you’ve chosen—like the one in our example.

What’s wrong is to believe there’s some reason you must do it. It’s OK to do it if you think you need to impose a discipline on yourself so you won’t do stupid things on the spur of the moment—like putting all your money in a stock your “gut” tells you is going to take off. What’s really, really wrong is to believe that investment professionals possess some sophisticated set of knowledge that explains why they know that you must always rebalance. If you make that mistake, you’ll pay them for what you think they know—and lose a gigantic chunk of your money on their fees.

WHAT DOLLAR-COST AVERAGING CAN AND CAN’T DO

Dollar-cost averaging is a myth that’s usually harmless; in fact, it can be beneficial because it imposes a good discipline on a person with an intention to save regularly. It may even be an essential discipline for a struggling investor. But it’s another example of a strategy that people think can do something for their investments that it can’t do.

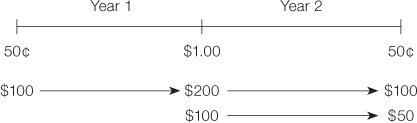

So let’s explain why dollar-cost averaging won’t do what many people think it can do. We’ll use a column that one of the most insightful economists in the world, John Kay, wrote about it as our starting point. A regular columnist for the Financial Times, Professor Kay stated the argument for dollar-cost averaging as follows3 (we have changed his pounds to dollars for the U.S. reader; also, in Britain “shares” means shares of stock):

Here is a scheme for beating the market that really works. Imagine a volatile share that sells for 50¢ in odd years and $1 in even years. If you invest $100 every year in this share, over a 10-year period you will have accumulated 1,500 shares at an average price of 66.7¢, well below the average market price, which is 75¢.

In odd years you get 200 shares for your $100, while in even years you get 100 shares for your $100—which comes to 66.7¢ a share on average. It does sound like it beats the market. You buy shares at an average price of 66.7¢, but the average market price is 75¢. You’re buying at a discount on average—or so it seems.

But does it really beat the market? No, it’s kind of an optical illusion. It’s easy to check. Let’s try it for only two years. Look at Figure 7.

You invest $100 at the beginning of year 1 when the price is 50¢ (because year 1 is an odd year), which then doubles to $200 by year 2 because the price doubles to $1. Then you invest another $100, so you’ve got $300, which gets cut in half by the end of year 2 so you wind up with $150.

What did the market do? The market started at 50, and at the end of the second year it went back to 50 again, so the market was flat. No, you didn’t beat the market. You invested $200, but you wound up with $150. You lost 25% of your investment while the market lost nothing.

But what if we flip-flopped and let the price be $1 in odd years and 50¢ in even years? Then you start with $100, which halves to $50. You invest another $100, so you’ve got $150, which doubles to $300. This time you beat the market.

FIGURE 7 Dollar-Cost Averaging

So whether or not you beat the market depends on which year you started. Not very conclusive, is it? This is no better than random. Half the time dollar-cost averaging beats the market, and half the time it doesn’t—at least in John Kay’s example.

Does Dollar-Cost Averaging “Work”?

Financial advisors who advocate dollar-cost averaging are really just recommending that their clients invest regularly. If their clients think this strategy will help them beat the market, well, so much the better—the added incentive might help them maintain the discipline.

We’ve seen in one example that dollar-cost averaging sometimes “works” (beats the market) and sometimes doesn’t. It depended on where the market started. It showed at least that it doesn’t always work. But does it usually work? How often? To answer that question, we must first pose the obvious additional question: Compared to what?

Dollar-cost averaging is the best plan if you have no alternative—that is, if the only way you can invest is by setting aside a regular amount out of your paycheck at regular intervals. But if you do have an alternative, what would it be? It must be that you have cash on hand that you could invest earlier than at those regular intervals. So let’s compare dollar-cost averaging with investing all at once right at the outset.

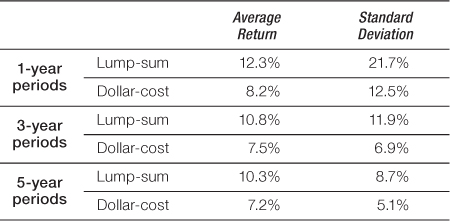

Let’s assume the two alternatives are (1) taking a lump sum and investing it in stocks all at once or (2) dividing it into equal pieces and investing it in the stock market at equal intervals—say, monthly—over time. Which one is better? This is a comparison we can make.

The Historical Advantage of Lump-Sum Investing over Dollar-Cost Averaging

We ran historical simulations for every monthly-rolling one-year, three-year, and five-year period during the 83 years from 1926 to 2008. In each case, we compared the rates of return on (1) investing a lump sum at the beginning of each period in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, and (2) dividing the lump sum into equal monthly amounts and investing it monthly over the period. The portion of the lump sum that is not invested in the stock market with dollar-cost averaging is invested in one-month U.S. Treasury bills while waiting to be invested in stocks. The results are shown in Table 4. This table shows that, on average, investing a lump sum all at once gave you a much better return than investing piecemeal with dollar-cost averaging. Investing a lump sum, however, also gave you a higher variability (standard deviation) of returns—they fluctuated more. You could interpret this higher variability (as MPT does) as higher risk.

TABLE 4 Lump-Sum Investing vs. Dollar-Cost Averaging

Source: Study by Michael Edesess.

So, as usual, higher return is available only with higher risk. The historical study makes it clear that dollar-cost averaging does not, by some miracle, transcend this risk-return relationship.

THE TRUTH BEHIND THE GOLD(EN) RULE

“Gold is a hedge against inflation” is right up there with the most frequently heard quotes on earth, like “better safe than sorry.” But what does it mean? Presumably, it means that if the dollar (or some other major currency) gets so inflated in a few years that you can only buy half as much or a tenth as much in consumer goods—say, food—with it, then gold will retain its value. You’ll still be able to buy the same amount of consumer goods with gold.

Well, it’s plainly not true. First of all, you can’t even buy food with gold. No one will sell it to you. You’ll have to go exchange your gold for dollars first.

So if the dollar gets so inflated that you can only buy half as much with it, does that mean that your gold will buy twice as many dollars as it did? It sounds right, but it doesn’t work. Gold isn’t used as a currency anymore and probably never will be. There’s no reason why it should retain any particular value in terms of a currency. It’s free to float, just like a lot of other high-value items that have value because they’re, say, nice to look at, or because speculators think they’ll be worth even more later—like fine art. Such items have prices that fluctuate wildly and unpredictably. Their prices bear little or no relation to inflation, especially in the short run—and that short run can be quite long indeed.

In an interesting and informative article, “The Golden Dilemma,”4 Claude B. Erb, a former investment management company executive, and Campbell R. Harvey, a professor of finance at Duke University, examined the argument that gold is a hedge against inflation. They found no support for that argument. On the contrary, gold ownership poses a much greater financial risk than inflation itself.

Gold wasn’t actively traded until 1975, after President Nixon took the United States off the gold standard. Erb and Harvey present evidence that shows that the price of gold in all major currencies has fluctuated from 1975 to 2012 much more than the currencies’ exchange rates. Hence, over that time (the only period of record with floating gold prices), holding gold subjected the owner to more risk than merely holding the wrong currency.

Erb and Harvey explore whether gold can hedge against unexpected inflation by investigating whether gold price changes correlate with changes in inflation rates. If year-to-year gold price changes correlate with inflation rate changes, then gold could be used to hedge against unexpected inflation. But these researchers find no such correlation. Their conclusion is that gold does not hedge against unexpected inflation in the short run.

In the longer run—10-year periods—annualized gold returns have fluctuated much more widely than inflation rates. “There has been substantial variation in …10-year annualized gold returns: from as low as -6% per annum to as high as +20% per annum,” Erb and Harvey write. “Over the same time period, the low and high inflation returns were +2.3% per annum and +7.3% per annum. [This] suggests that gold is not a very effective long-term inflation hedge when the long-term is defined as 10 years.”

“Gold is a hedge against inflation” is just another myth, nothing more.

SUMMARY OF DEADLY TEMPTATION #5

1. If total fees in your 401(k) are more than 1%, it is better to invest only up to your employer’s match, pay taxes on the rest, and invest it in low-cost funds outside the plan.

2. No theoretical or empirical reason or expert knowledge implies that it is right to rebalance your portfolio regularly; in some cases, it can even cause you to lose control of your risk.

3. Dollar-cost averaging, while it can impose a useful discipline on an investor who needs to save regularly, provides no other investment benefit.

4. Gold is not an effective hedge against inflation; in fact, holding gold as an asset is much more risky than the risk of inflation itself.