CHAPTER |

1 |

INTRODUCTION

The pace of change is accelerating from incremental to revolutionary, driven by globalization, information technology, and deregulation (Graetz, Rimmer, Lawrence, & Smith, 2006). Billion dollar industries are simultaneously being created and destroyed in rapid succession (Diamandis, 2013). Without management approaches to keep pace, we will find it impossible to comprehend and adapt to an unfolding reality that is uncertain, ever changing, unpredictable (Boyd, 1986). As the world moves to an ever faster clock cycle, so must our management techniques change to keep pace (Hodgson & White, 2003). All industries are challenged by this problem and some industries are challenged by it almost continuously. While many small projects face this challenge, so do billion dollar projects critical for national security. This increasing phenomena is raising the stakes and risks for projects, organizations, and nations.

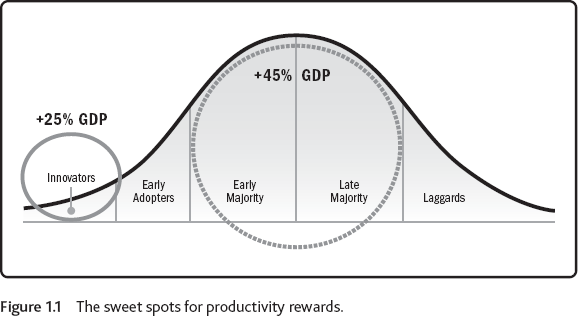

Studies indicate a relationship between technology adoption rates and national wealth (Comin, Easterly, & Gong, 2010; Comin & Hobijn, 2012). Delays in technology adoption may account for a 25% reduction in GDP. A study by Diego Comin and Martí Mestieri (2010) indicates even greater benefits from pervasive adoption of technology versus early adoption. Delays in pervasive adoption indicated a further 45% reduction in GDP. Taken together, the studies suggest that up to 70% of differences in cross-country per capita income can be explained by delays in technology adoption (Nobel, 2012). More flexible project management methods are therefore required “to regain the central place it should never have lost in the management of strategic initiatives, innovation, and change” (Lenfle & Loch, 2010). Project management techniques should support both innovation and more rapid and broad technology adoption as indicated in Figure 1.1 based on Roger's (2003) technology adoption life cycle.

This book combines management research with advice from experienced practitioners to document a range of practical approaches that can be used to manage projects in dynamic environments. Traditional project management undermines performance because it is designed for relatively static environments and focuses on the management-as-planning view of control (Koskela & Howell, 2002). Many managers now work in dynamic environments like that described Table 1.1.

In dynamic environments, unavoidable change occurs at a higher rate than it is practical to re-plan. A manager in a dynamic environment can be likened to a kayaker in white water rapids. Forcing a pre-conceived solution is like fighting the current. In dynamic environments, the manager should harness the current of change and intelligently steer toward the optimal result. This practitioner-focused book introduces the project management techniques that help steer work in this fashion. The techniques are particularly informed by three studies specifically dealing with the problem of dynamism. The studies involved interviews and focus groups with project managers to find out how they dealt with rapid change. Participants were project managers from ten different industries including: defense, community development, construction, technology, pharmaceutical, film production, scientific start-ups, venture capital, space, and research. The subjects covered included planning styles, culture, communication, and leadership in dynamic environments.

Table 1.1 Contrasting static and dynamic environments.

| Static Environments | Dynamic Environments | |

| Pace of change | Slow | Rapid |

| Predictability | Achievable | Difficult to achieve |

| Business cases | Stay valid for long periods | Rapidly outdate |

| Change impact | Mostly causes problems | Creates opportunities and problems |

Chapter Summaries

This chapter introduces the book and provides a synopsis. The method used in the primary research is described along with the participants.

Chapter 2 – Dynamic Environments

The challenges of dynamism are introduced in this chapter, explaining how it is an increasing problem for project management across all industries, with high stakes for national wealth and security. Dynamism is defined with examples given. The key challenge of dynamism—difficulty planning and controlling—is discussed. Traditional responses to dynamism are reviewed.

This chapter describes the dynamic planning process, led by a vision, and guided by desired outcomes. The iterative approach with stage gates, feedback, and evolving detail is discussed, along with emergent planning, simplification, recursive design cycles, prototypes, pilots, staged releases, and the cost of lost opportunity.

Traditional project management for static environments is focused mostly on a “management-as-planning” view of control, but in dynamic environments the plan outdates at a pace that makes it unhelpful for predictions and impractical to maintain. A range of alternate control approaches are discussed in this chapter, including input control, behavior control, output control, diagnostic control, interactive control, belief systems, and boundary controls.

Chapter 5 – Dynamic Culture and Communication

The culture of the project organization can affect how successfully it deals with rapid change. Cultures more suited to dynamic environments are described here. Case studies are presented, including Google, NASA, IBM, and The Spaceship Company. A range of communication approaches customized for dynamic environments are discussed encompassing regularity and formality.

Chapter 6 – Dynamic Leadership and Decision Making

Leadership and decision-making approaches suitable for mitigating dynamism are discussed in this chapter, including the need for flexibility, and situational awareness, collaboration, and pragmatism. Leadership qualities from the literature and from successful practitioners are outlined. A number of decision-making strategies are explained including: delegated decisions, decision making focused on speed and reasonableness, high levels of situational awareness, and pre-planned responses.

Chapter 7 – Dynamic Experimentation

Experimentation, discovery, and selection processes can play an important role for organizations working in environments with high levels of unknowns. This chapter discusses practical application of these techniques giving examples of their use in high-stakes environments.

Chapter 8 – Dynamic Practitioner Guide - Principles and Techniques

This chapter summarizes all the findings from the previous chapters into a quick reference guide of principles and techniques.

Data Sources

In this book, ideas are presented from four different sources:

- Scientific literature: The results of studies documented in peer-reviewed scientific journals on project management. A full list of references is provided at the end of the book.

- Interviews and focus groups of experienced senior practitioners.

- Case studies, interspersed throughout the book but dealt with in detail in the final chapter.

- My own views and thoughts from 30 years of practice and research.

Interviews and Focus Groups

Throughout this book are sections that include observations from research study participants, along with some non-study case examples. I have conducted research aimed at identifying management approaches used by practitioners in the field to manage rapid change during the conduct of projects. The objective of the studies was to discover how project managers approach projects in dynamic environments, and to refine the theory of how to best manage projects significantly challenged by dynamism. The studies included in-depth interviews and focus groups with a broad range of project managers who were challenged by dynamism. Participants were required to have the following attributes: (a) be senior project management practitioners or process designers, (b) have at least ten years’ experience, (c) be working in an organization that had been operating for at least 10 years (the start-ups selected were excluded from this condition), and (d) demonstrate they were significantly challenged by the dimension of dynamism with reasonable examples. The spread of participants across diverse industries and countries ensured that a broad range of approaches to managing dynamic environments could be discovered, and any commonalities identified. Any identifying information was removed from transcripts. In the first part of the research study, 31 project managers were interviewed, and in the second part of the study, three focus group interviews were conducted with 16 project managers in order to verify and expand upon the findings of the first study. Both studies included practitioners across 10 industries (defense, community development, construction, technology, pharmaceutical, film production, scientific start-ups, venture capital, space, and research). From the results, a theoretical model, called the Model for Managing Dynamism in Projects, was developed. The approach used in this study relied upon participants’ own perceptions of dynamism. Note the perceptions outlined in this qualitative study may not be shared across all project managers, and this study did not attempt to measure the benefits of the results or the negative side effects of using the approaches. This study deliberately used “maximum variation sampling” to obtain views from diverse industries to facilitate cross-pollination of ideas. However, it is possible that the approaches used in one industry are not applicable in another. While meeting the aims of the studies, the sampling technique and qualitative research design means that results cannot always be generalized to all project managers within each of the participants’ industries, so practitioners must use professional judgment when interpreting the findings.

Interview Participants

Table 1.2 Interview participant descriptions.

| Position | Industry |

| Planning engineer for road tunnel construction company | Construction |

| Project office manager for green-power generation | Construction |

| Project management leader for government space agency | Aerospace |

| Post-conflict-reconstruction project manager for international aid agency | International Community Development |

| Community development project manager for aid agency in Middle East | International Community Development |

| International post-disaster recovery-aid project manager | International Community Development |

| Manager of a program of drug-development projects | Pharmaceutical |

| Manager of a drug-development project | Pharmaceutical |

| Military campaign manager – regional assistance (post-state collapse – Solomon Islands) | Defense |

| Military campaign manager – regional assistance (post-conflict – Timor) | Defense |

| Military procurement program manager – fighter jets, warships, etc. | Defense |

| Documentary film production manager | Film Production |

| Feature film director | Film Production |

| Feature film producer and director | Film Production |

| Manager of a project to develop new power-storage technology | Start-up in Science/Technology |

| Manager of a series of projects to develop new power-generation technologies | Start-up in Construction |

| Manager of a program of venture capital projects | Venture Capital |

| Manager of a research program | Research |

| Manager of several research projects | Research |

| Information technology project manager | Information Technology |

| Information technology software development project manager | Information Technology |

| Project manager of new data-center design and construction | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

| Project manager of IT infrastructure provision | Information Technology |

Focus Group Participants

Three focus groups were run to allow triangulation of results and to mitigate the effects of face-to-face versus online. Table 1.3 lists the roles and industries of the focus group participants. Quotes from focus group participants will be identified in the book by their industry or by the label “FG.”

Table 1.3 Focus group participant descriptions.

| Project and Role | Industry |

| Product development for a space launch company | Aerospace |

| R&D project to develop new ways of doing air-conditioning | R&D |

| Author of project management guide for international aid projects | Generic |

| Software development of new healthcare system | Healthcare |

| Software development in IT | IT – Generic |

| Software development in IT | IT – Software |

| Adoption of new type of email service | IT – Networks |

| Software development in IT | IT – Generic |

| iPhone and Android app development | Software Development |

| Rapid large-scale wireless network rollout | IT Networks |

| Rapid HR system deployment | ICT |

| New traffic control system deployment | Engineering |

| Post-conflict reconciliation project | Humanitarian Aid |

| Post-conflict reconstruction project | Post-Conflict Reconstruction |

| Disaster aid project | Humanitarian Aid |

| New space vehicle development | Aerospace |

Publications Emanating from the Research

Collyer, S., & Warren, C. M. J. (2009). Project management approaches for dynamic environments. International Journal of Project Management 27(4), 355–364.

Collyer, S., Warren, C. M. J., Hemsley, B., & Stevens, C. (2010). Aim, fire, aim – Planning styles in dynamic environments. Project Management Journal 41(4), 108–121.

Collyer, S. (2013). Managing dynamism in projects: A theory-building study of approaches used in practice. Brisbane, Australia: The University of Queensland.