4

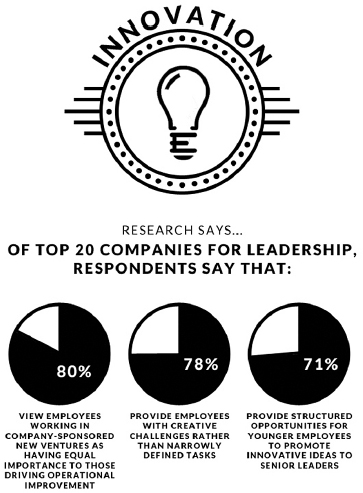

Innovation

Investment decisions or personal decisions don’t wait for the picture to be clarified.

ANDY GROVE

Make Change Work for You

Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, believes that people need to think beyond what they think is initially possible. “I tell people that human nature is not very amenable to change, so most people like the standard way of doing things. But I say that change equates to opportunity. If you look for opportunity to come out of change, you can always find it. You can spend your time looking for the difficult elements of change, but opportunities are always there. In our business there’s another tenet that’s important, and it’s follow the capital or follow the growth. You want to go where the business is booming, where the growth is, where the capital is.”

Change is something that Lance has embraced throughout his career. “As I reflect back on my own experience, some of the best career moves were made in the face of change. Specifically, I worked on integrating several mergers about a decade ago. This wasn’t glamorous work, but it put me in a position to be on the frontline when we were merging Conoco and Phillips to create ConocoPhillips.”

If you don’t take a chance, you won’t make a difference. That’s a mantra that has served Lance well. “This job provided a unique opportunity for me to meet people on both sides of the company, because I had come from a third company as part of that merger. I got to see how each company operated, how they ran their businesses, and how they made tough allocation decisions around capital, people, and resources. I learned a lot about the functions that support the main business of engineering and operations, such as finance, legal, and human resources. I gained exposure to all facets of the business as I went through this. Again, at the time it didn’t feel like a glamorous assignment, but I put myself in a position very purposefully to gain insights about the businesses and the different company cultures. Ultimately, I was better prepared to succeed in the new merged company as we moved forward.”

Make the Most of a Challenge

Fernando Aguirre, former CEO of Chiquita Brands, was a rising executive at Procter & Gamble when he was given the opportunity to go to Brazil to see if he could turn around its failing operations. After Aguirre presented his three-year turnaround plan, the CEO of P&G, Edwin Artzt, said, “Fernando that’s great, but three years is unacceptable. I want you to do it in one year.” Aguirre had his doubts. “But I didn’t tell anybody else that. I was then young and naïve and resilient. And I said [to myself], ‘All right. I’ll figure out a way.’ ”

Artzt also gave Aguirre permission to call him if he needed help. He told Aguirre: “You have a direct line to me anytime you need or want a decision that you don’t get from anyone else.” But Artzt did not give Aguirre a blank check; the turnaround needed to happen within a year, or P&G might close its operations in Brazil, and with it the careers of Aguirre and his Brazilian colleagues.

Not only was Aguirre on a short time frame, he had to find a way to make a newly built factory that produced Pampers diapers succeed. Its losses were dragging down the Brazilian operation. One reason was that the product line was too diverse—different Pampers for boys and girls, both in multiple sizes. Aguirre and his team slimmed the product line to unisex diapers in just three sizes—small, medium, and large. That move did the trick.

As Aguirre explains, “We broke even the first year. We made $8 million the second year. We made $25 million the third year and my fourth year we made $45 million of profitability and the revenue was $450 million. That made my career.”

SOURECE: 2013 BEST COMPANIES FOR LEADERSHIP HAY GROUP1

Innovation. Individuals who have moxie are not content with the status quo. They are continually seeking to acquire new skills and apply them in new ways.

Sergio Marchionne

He does not look the part of an automotive mogul, with his sweater, cigarette, and slightly rumpled clothing. But looks in this case do not tell the story. He may be the auto executive with the most challenging job in the world: reviving the fortunes of two flagging automakers, Fiat and Chrysler. His name is Sergio Marchionne, and as CEO of both automakers, he led a turnaround effort that startled those who do not know him, though it has not surprised those familiar with his track record.

Marchionne was born in Italy but immigrated to Toronto with his family when he was a teenager. The fact that he did not speak English was a stumbling block, and his teen years in school were not marked by academic success. But unlike others his own age, he did have a remarkable ability at cards. He would accompany his father to the local Italian solidarity club and join in games of poker with his elders. His tolerance for risk was high and he seemed to keep his cool, two traits that would hold him in good stead in his career.

After buckling down to the books, he went to university and did well enough to earn a degree in chemistry. He gained a job with a Swiss company, and ended up in various manufacturing positions in Brazil and Europe. Marchionne proved himself an adept manager and ended up running SGS, a Swiss subsidiary of Fiat. He turned the company around, which earned him the notice of Fiat’s senior management.

As the twenty-first century dawned, the company that had defined Italian manufacturing prowess—and was involved in many other businesses as well—was foundering. The biggest cash drain was Fiat Auto, and Marchionne was tapped to run it. Urgency was the order of the day, as the company was close to insolvency. Some executives would have withered under the assignment; Marchionne did just the opposite. He thrived.

Jennifer Clark, who profiled Marchionne in her book Mondo Agnelli: Fiat, Chrysler, and the Power of a Dynasty, writes, “Marchionne’s unusual ability is that he can see what actually needs to be done, and then cajoles and goads his flat management structure of dozens of direct reports in weekend meetings to achieve the goal.” A UBS analyst put it best: “Marchionne doesn’t let go. That’s what his strength is. He is good at strategy and at execution.” Under Marchionne, both Fiat and Chrysler have turned the corner, at least for now.

The balance between vision and execution is akin to right- and left-brain thinking. A visionary thinks about what can happen; he envisions the future in very specific terms, not simply in outcomes but in what it will take to produce the outcomes. The execution part is getting people in place and providing them with resources to succeed. It also means holding people’s feet to the fire.

Marchionne can be a demanding boss. He expects his top lieutenants to burn the midnight oil, including working weekends. The work is tough, but he holds himself to the same standards he expects from his team. When Marchionne took over Fiat and Chrysler, heads rolled. But with both companies in dire straits, decisive action was necessary. In times of crisis a leader must often move quickly. That said, Marchionne has a sense of humility. When he spoke to Chrysler employees for the first time, in 2009, he said that he needed their ideas and their effort to succeed.

Marchionne likes to be close to the action. At Fiat he spent time walking around getting to know people, and when he identified his key people he pulled them toward him in a matrix management style that enabled everyone to stay close. At Chrysler he did the same. As one executive commented, by working closely together, employees kept one another in alignment with corporate directives.

Marchionne did not take over the plush office on the top floor of Chrysler’s headquarters. Instead, he located his office on the engineering floor, to be close to the people who were revamping the product line.

He insisted that the Fiat engineering team share its expertise with Chrysler engineering teams, a process that would accelerate the development of smaller vehicles to meet the automaker’s need for improved fuel efficiency. He also empowered his managers to take a look at the Chrysler lineup, especially Jeep, an iconic brand.2

In making these changes, Marchionne sent a signal that he was actively engaged in the business, but that if the company was to be successful it would need to think and do differently. It would need to innovate, and in this regard, he is a model of a leader who exemplifies what it takes to energize an organization through the spirit of innovation.

*****

Good leaders are those who, by nature or by training, learn to look over the horizon. Like scouts, they are attentive to any form of change, such as a shift in consumer preferences, the rise of a new competitor, or the altered landscape of an economy. They are forever comparing what is happening now to what happened before and what could happen next. They are tuned to the future. Their forward-themed outlook is not merely one of observation, it is one of application. That means that, even as they assess what is happening now, they are thinking about what’s next. That gives rise to innovation.

Creativity, which we explored in the previous chapter, is essential to innovation. It is up to managers to find ways to encourage it so that employees can use it. Innovation, to my way of thinking, is applied creativity. Leaders have to enable employees to be creative by providing conditions that let the imagination flourish. They also must take what emerges and push, or pull, it throughout the organization. And that is not easy.

Obstacles to Innovation

Many organizations regard innovation as the Holy Grail, that is something for which they are searching. It provides the path a company needs to become more creative, productive, and ultimately more profitable. According to one global study of major companies, senior executives rated the need for innovation as a nine or ten on a ten-point scale. They viewed innovation as a source of growth. Sounds good, but more and more there is pessimism about innovation. This same study showed that these executives rated their satisfaction with innovation at no better than five on a ten-point scale.3

Obstacles to innovation fall into three categories. One is hitting a plateau, not because there is less innovation but because the returns are smaller. For example, as described in The Economist, the biggest gains in life style comfort and productivity came from “electricity, internal combustion engines, plumbing, petrochemicals, and the telephone.” These are all delivering good returns, but not quantum returns. Could there be new technologies in the future? Of course, but no one has yet identified what they are.4

Two, innovation contributes to productivity but, as economists Tyler Cowens and Charles Jones have shown, productivity has decreased. For example, according to research, “in 1950 the average R&D worker in America contributed almost seven times more to ‘total factor productivity’ ”—return on investment, so to speak—than he did in the year 2000. Furthermore, it’s taking longer to innovate because technology is racing to catch up to science.5

Three, innovation today seems slower than it once was. The improvements to household living—electricity, refrigeration, air conditioning—occurred in the previous century. Medicine has enabled humans to live much longer: life expectancy in the United States is over seventy-eight years. Yet the killer ailments—heart disease, cancer, stroke, and organ failure—remain with us, despite hundreds of billions of dollars spent on research.

The slowdown in innovation may hinder national productivity. The average growth rate of U.S. productivity in the twentieth century was 2 percent. Robert Gordon, an author and professor of social science at Northwestern University, argues that future growth may average 1 percent. Invention in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as Gordon explains, fueled innovation starting with electricity, indoor plumbing, and the internal combustion engine. The post-World War II period saw the introduction of jet travel and the proliferation of computer processing, and in the last decade of the twentieth century “the marriage of communications to computer” spread the power of the Internet, which today rules nearly every aspect of business. Repeating such breakthroughs, as Gordon says, will be difficult.6

Obstacles to innovation will only increase, but that does not mean we should abandon our quest for it. We simply need to explore new ways of looking at it. That begins with leadership. It falls to leaders to create conditions in which individuals can contribute ideas about how to work more efficiently and productively. Such openness may not lead to breakthroughs, but over time they will spark patterns of behavior that encourage people to talk about issues and challenges and how to solve them. It is only within this milieu that creativity can occur, and in turn be applied to innovation.

Setting Ground Rules for Innovation

CEO Rich Sheridan’s firm, Menlo Innovations, true to its name, makes its livelihood by innovating. A programmer from his teens, Sheridan believed that there had to be a better way to create software, which spurred him to create a company that did things differently. Sheridan said, “Where I learned to manage by mimicking other people above me was in environments of fear… And you’re like, ‘Oh, that’s the way you manage people.’ ” It was fear. It was artificial fear.

“Managers would say to employees, ‘Are you staying late this weekend? I mean, we got a deadline to meet. If we don’t meet that deadline we’re gonna lose that account. If we lose that account that could cost you your job.’ And it’s like, was any of that true? I have no idea, but I’m going to work this weekend. But now I’m operating out of fear. You’re not going to get innovation in an environment like that.”

Chester Elton agrees: “I think the biggest inhibitor to innovation in organizations that I’ve seen is where failure is punished. The message is, ‘Boy, you better be sure that this is gonna work because if it doesn’t work heads will roll.’ Companies that are most innovative to me embrace failure.”

So when Sheridan founded Menlo Innovations with his business partner in 2001, he resolved, “Number one thing, hands down, you have to pump fear out of the room. You cannot innovate in an environment of fear because fear causes your body to produce the powerful chemicals adrenaline and cortisol. These chemicals shut down the most interesting parts of your brain, because the blood is now being channeled to your extremities so you can run and to your heart so you get enough oxygen to run. Blood is channeled away from the front—prefrontal cortex of the brain. And now you’ve lost all ability to be creative, to be imaginative, to be innovative, because now you’re in reptile mode.

“So creating the right environment and working hard to get fear out of the room is important. If people aren’t afraid they will begin to trust one another. If they trust one another they might begin to collaborate. And if they collaborate suddenly you will get creativity, innovation, imagination! And that’s what companies are looking for.”

Driving out fear is only the first step; you need to take it further, according to Sheridan. “We want joy here, defined as the people for whom we’re designing and building the software love what we’ve done. They are delighted and we’ve made their lives better. So that’s that whole idea of working on something bigger than yourself.

“We focus our cultural intention on the outside world, on the effect we’re going to have on the world. And I think that’s really important. And all of our processes, all of our behaviors, all of our hiring practices, everything we do is built out of a shared belief system that all of us in the room believe will produce that kind of joyful outcome for our customers. And so I think intentional culture and the shared belief system that brings that intentional culture to life every day is what makes all the difference.”

Discipline of Innovation

Innovation does not occur by accident. It requires discipline. Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, says, “Leaders must be patient and willing to tolerate mistakes and failures. Like we say in our business, ‘You’ve got to be willing to drill a few dry holes.’ So innovation is not a quick thing; it takes time. I think you have to set the right tone culturally. You have to let people know it’s okay to ask and it’s okay to dream.”

“Innovation for the sake of innovation may be noble,” says Lance, “but to be practical, it has to be capable of being transported to the field; it has to have a business application; and it has to impact the business in a visible way. You also need to understand the economics of innovation. At the end of the day we have to be good stewards of shareholder money, and as leaders we have to show that innovation will improve upon the business.”

The willingness to move swiftly is an imperative when it comes to innovation. As Aguirre says, “I think most people now realize that if you’re not changing and evolving your business models you’re not going to be successful.” Once managers were told to hold to strategies for a decade. “You can’t do that anymore,” says Aguirre. “The world is so fast. The world is changing so much. Competition is better. Technology is now so advanced that everyone is developing products as good as or better than yours. So you have to keep improving, and there’s no way to improve your business models, whether you make or sell products, or whether you are in the service industry, you can’t improve without some level of innovation.”

Aguirre emphasizes the need to support innovation: “You need to put effort and investment behind it. At Chiquita we ended up investing a ton of money my first five years to expand the brand. The brand is fantastic, very powerful, very well known, but we only had it in bananas. And I felt that one of the most important things we needed to do was diversify the company into other product categories and also to expand the brand. We needed to leverage a fantastic brand. So we invested and I talked a lot about the expansion and diversification of the business.”

Innovate in New Ways

“The key to being consistently innovative,” argue Drew Boyd and Jacob Goldenberg, authors of Inside the Box: A Proven System of Creativity for Breakthrough Results, “is to create a new form for something familiar and then find a function it can perform.” The authors cite the example of a contact lens; it’s a corrective lens without a frame. This is a form of subtraction. Addition would be adding lenses together, such as telephoto or close-up lenses. Nestlé did something similar when it developed a line of iced teas to be drunk warm or heated during colder months. The beauty of this approach, argue professors Boyd and Goldenberg, is that “The most consequential ideas are often right under our noses, connected in some way to our current reality or view of the world.”7

Ways to innovate are as myriad as business models. In fact, one form of innovation has no real business model at all. We call it “Big Science,” a collaborative effort among many different interests to build one thing. An example is ATLAS, the world’s largest microscope. As described in The Economist, ATLAS is “45 meters long, 25 meters tall, and weighing as much as the Eiffel Tower.” ATLAS resides in a cavern, where it is used by scientists at CERN “to probe the fundamental building blocks of matter.”

The secret to ATLAS’s success is the buy-in that thousands of engineers and scientists from around the world have devoted to it. Their motive was not profit, it was exploration. And for that reason it has been a success. Physicists using it proved the existence of the Higgs boson, known as the “God particle” because it may be a part of everything we know, large or small. What the nonscientific world can learn from Big Science is that innovation can occur on a global scale if people are united in purpose.8

One company with ambitions like those of Big Science is Google. And with a research and development budget approaching $7 billion (as of 2013), it has the heft as well as the brain power to make it happen. Google’s biggest asset, however, may be the commitment of its cofounder Sergey Brin. While Larry Page serves as CEO, Brin is the chief technology officer. He has direct involvement in Google’s laboratory, Google X, which is inspired by such past labs as AT&T’s Bell Labs and Xerox’s PARC.

“Sergey’s direct involvement,” says Richard DeVaul, who works at Google X as a rapid evaluator, “is one of the ways this environment gets supported.” Such personal commitment, according to Bloomberg Businessweek’s Brad Stone, who wrote about Google X, is one reason that the lab is able to attract top-notch talent.

Key projects include Google Glass, a computer in eyeglasses form, and the self-driving automobile, both favorites of Brin himself. But the lab is more ambitious. Its head, Eric “Astro” Teller, addressed the 2013 South by Southwest (SXSW) conference by saying, “The world is not limited by IQ. We are all limited by bravery and creativity.” On the drawing board are projects like an airborne turbine that generates power by flying in circles, as well as an initiative to bring Internet access to undeveloped parts of the world. Their mission is bold—moonshots for technology and science. As Stone wrote, Google X (the Google innovation laboratory) is designed to make “those million-to-one scientific bets that require generous amounts of capital, massive leaps of faith, and a willingness to break things.”9

Google also sponsors the Solve for X project, which hosts conventions centered around a collaborative approach to solving global issues; one conference included presentations on inflatable robots, detection of early Alzheimer’s via eye exams, and nuclear fusion reactors. As Teller puts it, “We’re as serious as a heart attack at making the world a better place.”

That statement sums up what is necessary for innovation. Funding yes, but also the faith to experiment as well as the recognition that failure is an option. While line managers often do not have access to the spigot that controls the flow of capital, they can encourage their people to think for themselves and to undertake new projects with the understanding that mistakes will occur—and when they do, they can serve as vital lessons.

Innovation: Systems Approach

What works for Rich Sheridan at Menlo Innovations is a systems approach to innovation: “We pair our [software programmers] together, two to a computer for five working days, and then we switch the pairs every five days. It ensures that everybody on the team is going to interact with everybody else on the team.”

The office has an open-space setup. Sheridan said: “We’re all working in the same room together, with no walls, offices, cubes, or doors. This means that at least we’re spending time together.” Such proximity fosters conversation and coordination that create opportunities for people to collaborate with one another to get the work done. Project tracking is precise but somewhat old-fashioned, especially for a technology firm. “We’ve created an interesting system of no ambiguity where we write stuff down on these little story cards,” said Sheridan. “We pin the story cards on the wall under people’s names. So people come in and they know exactly what they should be working on. And now they can actually get meaningful things done.”

The systems approach welcomes client interaction. “In our world, we invite our clients in every five business days,” said Sheridan. “And they reconnect with us in an event we call a ‘show and tell.’ And our ‘show and tell’ is actually reverse ‘show and tell.’ ” Rather than Menlo staffers revealing the work to date, the clients present it to the programmers. “By pulling our client into the process that way, they’re now mindful of the work we’ve just done… Software is very theoretical until it’s actually working, until people can actually touch it.”

It is important for staffers to see the clients interact with the software. As Sheridan says, “The clients are the ones with their hands on the keyboard touching the software,” with the people who worked on that software watching. There is “no interpretive dance in between, no ambiguity, see the emotion, see the eyebrows, see the folded arms, see the delight, see the smiles, hear the laughter, see the frowns, all that kind of stuff I think is really important.”

These client sessions also head off potential problems. “I mean, the fact that we get good feedback is great. It’s far more important when we get the negative feedback, hopefully constructive negative feedback. And one of the ways we make it constructive is we’re doing these check-ins every five business days, so if we made mistakes they’re not going to be big ones. They’re going to be little ones.”

“Think in Glass”

You don’t have to be a twenty-first-century company to innovate. In Murano, the glass-blowing district of Venice, innovation continues to be a watchword. And it has to be. According to the The Economist, contemporary glassworks, often located in Asia, are undermining this seven-hundred-year-old Venetian tradition. More than a third of glassmakers have shut their doors, and many continue to ply their trade by making kitschy, heavy glass souvenirs tourists once bought by the boatload. But that way of glassmaking is not the future.

Adriano Berengo, a glassmaker, continues to operate his Murano studio, but he has divided it into two parts. One side produces traditional glass; the other side he offers to artists. “Artists love new toys to work with,” Berengo said. “What we have to do is get them to think in glass.” Artists working in Berengo’s studio produce two works of art—one for the studio and the second for themselves, which they can put up for sale themselves. If a third piece is produced, Berengo and the artist split the take.

Murano, as The Economist noted, has prospered “through innovation, and concentrating on quality.” With innovators like Berengo and others, Murano may be able to add another century of tradition to its legacy. Again, innovation is not New Age; it belongs to any age. Nowhere is this more so than in Murano. Researching Venetian glass archives, Berengo discovered a way to make green glass using a technique from the sixteenth century called avventurina. Sometimes innovation involves looking backward to find ideas that may have been forgotten, but which have new applications in today’s world.10

Ask Questions and Listen

General John Allen, as the senior-most commander in Afghanistan, used to hold regular sessions with his senior staff, including three-star generals from Britain and France and three- and two-star combat commanders. He would present them with a big question, such as, “How do we get after corruption in Afghanistan?” or “When and how do we begin to turn over military/operational lead to Afghan forces?” (This latter question raises an agenda that General Allen is credited with turning into a success, as he was the commander who initiated the turnover in 2011.)

“The idea was to draw out my commanders,” Allen said. “You wouldn’t find more experienced combat leadership probably anywhere on the planet in one small spot—to bring them all together to create a common perspective and mentality on issues where we could have a good, strong give-and-take.” There was also push back. “If I felt that push back was valuable ultimately to me, providing greater focus or clarity in my orders or to change the order because it now makes better sense because of what I’ve heard, I’ve never hesitated to do that.” A leader’s job is to listen to what her direct reports say. “I think that’s a healthy environment to have. If they believe that, no matter what they say to you, you won’t change whatever it is you’re doing, then that effect is, it ultimately chills the kinds of conversation that you want to have between leaders, especially leaders in combat,” said Allen.

“Chalk the Field”

Jim Haudan, CEO of Root, says, “Innovation can only occur with the mind-sets that recognize that Big Ss come from small Fs, and that means big successes can only come from small failures. So if we can’t fail we will never succeed.” To do that, organizations must “fail forward fast,” says Haudan. “You need to hug the failures and embrace the failures” rather than run from them.

Chester Elton concurs: “One other thing I’ve found about innovative companies is when they go down the track of something that’s not working, they fail fast. So they figure out what it is, they take a shot at it, if it’s not working they kill it quick and they move on. So I think innovative thinkers and organizations are those that take measured chances, but they don’t let failure get in their way and they don’t punish failure.”

Toward that end, Haudan advises leaders to limit risk and go for “small, fast, and cheap.” For example, go for process improvements and incremental changes to products rather than entire new product lines. Use them as learning lessons rather than “bet-the-company options.” Once you have learned, you can take bigger risks, developing entirely new products or even product categories. Lessons learned on small bets will put the organization in a better position to take advantage of new opportunities.

Haudan notes a pitfall of innovation: applying it where it is not needed. “Innovation requires different management than operations,” he says. So he advocates that you “chalk the fields,” that is, determine what you will change and why. “There are places where you want absolutely no innovation, because reliability and predictability are key,” says Haudan. For example, security in bank or patient safety must be fail-safe operations. These are areas where you don’t take chances.

Reinventing Old Things

Innovation need not always be about what’s new. Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, says, “[Innovation] can be coming up with new ways to do old things. That includes getting rid of old work processes that don’t really add value to the company, its direction, culture, or the strategic objectives we’re trying to fulfill.” Innovation also requires “thinking about new ways to do existing processes while also killing old processes that don’t make any sense.”

Finding new ways of tackling old problems reinforces a culture of innovation. “If you pick the right opportunity, you can get a lot of mileage out of telling success stories. The stories go viral within the company and people recognize that, ‘Hey, we did something different,’ ” says Lance. Employees will note the change and say to themselves, “They killed this inefficient process. I don’t have to do this anymore. Isn’t that a great thing?” When such changes are publicized, notes Lance, “You get a lot of visibility and credibility for your willingness to innovate.”

Whether you find new applications for new technologies or use old ideas that offer new solutions, innovation is essential to the health of the enterprise. It falls to the leader to continue to push the organization to embrace creative ideas as a means of thinking and doing differently.

Closing Thought: Innovation

Innovation is often a work in progress. Sometimes people are willing to embrace something new, and when they do they expect instant results. As with many things in life, you have to keep doing it to become successful. More often, people resist innovation because it disrupts their comfort zone. When it does, they put up resistance. Again, it is necessary to keep trying. It falls to the mindful leader—one who looks for opportunity—to push the organization to do something different in the quest for improvement.

Innovation = Creativity + Application

Leadership Questions

- What are you doing to capitalize on your creative self?

- What do you do when you find your creative skills are not wanted?

- How are you helping others to maximize their creative abilities?

Leadership Directives

- Complacency is the bedmate of the status quo. Seek change and consider how it applies to you.

- Innovation is a change process. Apply your creative self to the situation around you. Sometimes you will innovate in your career, do something different. Other times you will need to innovate with your team to enable them to go in a new and different direction.

- Innovation begins with the openness to new ideas. Challenge yourself to embrace the possibility of change. And yes this will be disruptive.

- Learn to follow through on ideas that will improve things for your team, your customers, and your organization, not to mention yourself.

- Become a “go-to person” by using your creativity to effect positive change. You can do this by suggesting (or being open to) new ideas, solving problems, and collaborating with others.