2

Opportunity

The biggest human temptation is to settle for too little.

THOMAS MERTON

Making the Break

Chester Elton, best-selling author dubbed the “Apostle of Appreciation,” and his business partner Adrian Gostick had been colleagues at a previous employer. In the last year of their employment at that company, things did not go well. As Elton explains, “I consider us not being able to figure out how to stay with our past employer and still be productive as a huge failure. We should have been able to communicate better and work together in a more productive way. But we couldn’t find a way forward. No matter how hard we worked or how much success we had, we couldn’t make our bosses happy or find happiness ourselves.”

Elton credits his wife, Heidi, with providing him with the support he needed to go out on his own. According to Elton, “She said, ‘Look, I know you’re really struggling with leaving. You are a loyal guy. You love the company, but a company can’t love you back! Let me make this simple for you … you’re leaving. Let’s just figure out how.’ And the reason she said that is because, ‘This job is killing you. It’s literally killing you. I want my husband back. The kids want their dad back. So you’re leaving. Now, let’s just figure out how we’re gonna do that.’ ” That’s what a great spouse does for you.

Elton realized that he had to make a move. “Leaving is never easy, especially after nineteen years. But things change, leaders change, and you can’t always make the change. No one is to blame. I still have great friends there and their leader is a genuinely good man. It just wasn’t the right place for me anymore. It was time to move.”

The challenge of independence beckoned. “And yet the opportunity for us to be on our own and to create our own business, The Culture Works, has been so rewarding and so much fun and so engaging and so profitable. It was one of those things where I thought, ‘Geez, if I knew you could do this on your own I would have done this two or three years earlier.’ ”

Failure is not the end. “I think when you talk to people who are success driven, they really do look at those failures as ‘Here’s where we are now. Now what do we do?’ We can cry. We can laugh. We can stew in our juices or we can pick ourselves up and move along. And my response to failure has always been to just work harder. You just work harder, and the harder you work the luckier you get and the more success you have.”

Making the Most of Serendipity

In a recent conversation, Jim Kouzes, professor and author, told me his story of opportunities and serendipitous events. “My entire career has been a series of serendipitous events. I seem to have had accidental encounters with opportunities, and I guess I’ve been both lucky and smart enough to take advantage of each. For example, right out of university I joined the Peace Corps, and I was assigned to teach. I had no idea at the time how much I would enjoy teaching. I thought I wanted to be a Foreign Service officer. But when I got back to the U.S. I decided that I wanted to get a job in teaching.”

After three years working for the Community Action Training Institute, Kouzes was recruited by the School of Social Work at San Jose State University to run a grant project that provided training to mental health administrators in the San Francisco Bay area. That led to a job directing the Executive Development Center at Santa Clara University, which is where Kouzes met his eventual coauthor and business partner, Barry Posner.

“Barry knocked on my door the first day I was there in my new office at Santa Clara and said, ‘You’re in my office.’ I was initially surprised and said, ‘What? I thought the dean told me this was my office.’ Then he laughed and said, ‘Well, it is your office now, but it was my office.’ Then Barry said, ‘Since you’re new to campus, just let me know how I can help. If there’s anything you need I’d be glad to show you around. I also do some work with the Executive Development Center, and if there’s anything I can do to help out there let me know.’ And I said, ‘Great.’ I took advantage of that opportunity, and the result has been a rewarding three-decade collaboration. I learned two lessons from that early connection with Barry—and from all my other serendipitous encounters. First, knock on more doors. Knock on lots of doors. Second, always say yes when somebody asks, ‘Can I help?’ Yes is the only word that starts things.”

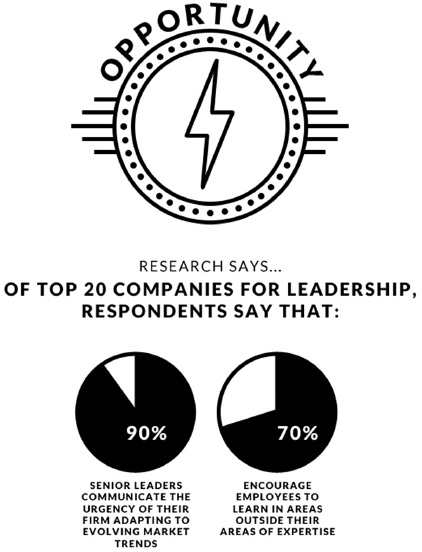

SOURECE: 2013 BEST COMPANIES FOR LEADERSHIP HAY GROUP1

Opportunity. Individuals with moxie do not wait for things to come to them. They seek new opportunities. They are seekers of the new and different.

Ben Hogan

When asked the secret of his success, this phenom used to say as if it were a secret, that “It was in the dirt.” Many have speculated about what he meant by that, but on the surface it meant that you had to do the work. He was a golfer and he spent hour after hour hitting golf balls off the grass and the dirt. But it went deeper. Dirt for him represented the determination that he brought to his game. Short in stature, his compact frame was wiry and muscled, unlike the lean lankiness of other golfers of his generation. Whatever power he generated could come from his arms, shoulders, torso, hips, and legs. And it is the latter two that gave him the most trouble. But it is the reason that he is revered to this day. He was Ben Hogan, champion golfer.

Born in Texas to impoverished parents, young Hogan learned the game at a country club near Fort Worth where he caddied. In those days, professional golf was hardly a profession at all; it was more akin to a group of itinerant gamblers rolling from town to town to compete for prize money that totaled little more than a few thousand dollars. Still, something about the game appealed to Hogan, and he decided to make it his career.

Nothing came easy to him. His first years on the tour were nothing spectacular, but he did win a few tournaments. During World War II, he served in the Army Air Corps and trained as a pilot. He never went overseas. Stationed in his native Texas, Hogan and had time, like other golfers in this era, to work on his game. It was after the war that he began to make a reputation, winning a number of tournaments including the U.S. Open and the PGA Tournament, known in professional golf as “the majors.”

But an event in 1949 defined Hogan’s life and ultimately made him the icon he is today. Driving home to Texas from a tournament in Los Angeles, a bus swerved into his lane and pancaked his new Buick and his legs. At the last moment, Hogan swung himself out from behind the steering wheel to shield his wife from the impact. By doing so he likely not only saved her from injury, but also prevented himself from being crushed by the onrushing steering column. Unfortunately, his legs were in the path of impact and they were mangled so severely that it was first reported that Hogan had perished in the accident.

Talk of Hogan walking again seemed premature. But during the long months in the hospital and then at home in recovery he resolved not only to walk again but to play golf. Somewhere in the back of his mind he resolved also to compete. Although shy and reserved, Hogan had built up a reservoir of goodwill among his fellow golfers, tournament officials, and even sportswriters. He was selected as the captain of the American team that traveled to Scotland in 1949 to play in the Ryder Cup. He did not compete but he led the winning team.

Perhaps it was being back in the golf world that tempted him to try again professionally. Upon returning to Fort Worth, he began hitting balls for hours on end. Then, in 1950, he pronounced himself ready enough and entered the Los Angeles Open, held at Riviera Country Club. He hit the course like a whirlwind, scoring well enough to place in the money, though it was difficult. His legs swelled upon walking, let alone playing golf, and they ached painfully during the four rounds of competition.

But it is what happened six months later that launched Hogan into golf history. He entered the U.S. Open at Merion Country Club outside Philadelphia. The U.S. Open is regarded by many as the toughest tournament of all; the course is typically rigged to be challenging, and it attracts the best of the best players. Hogan had won the 1948 U.S. Open, but that was on two good legs. Now he was hobbled, but he gave it his all.

As Dave Barrett explained in Miracle at Merion, the tournament took place only sixteen months after the crippling accident. Hogan willed himself around the course, playing thirty-six holes to seal a playoff berth then another eighteen the next day. Red Smith, legendary New York sportswriter, wrote, “Maybe once in a lifetime … it is possible to say with accuracy and without mawkishness, ‘This was a spiritual victory, an absolute triumph of will.’ This is that one time.”2

The 1950 U.S. Open was Ben Hogan’s moment. It was at Merion that he established himself as a player who defied the odds and used a combination of guts and guile to win. Hogan had confidence that he would and could do well. He had prepared himself to compete at the highest level and he did. This was Ben Hogan’s moment and he played to a tee.3

*****

Seizing the moment is what Ben Hogan did and what leaders who succeed do. Opportunities, as the adage goes, come to those who seek them. And that is critical for a leader. Few, if any, are content to sit back and wait for things to happen. They look for windows of opportunity where they can apply what they know and do to what needs doing. They are opportunistic in mind-set, and their need to succeed drives them to take advantage of what happens next.

Facing Adversity

Opportunity also requires perseverance. Max De Pree, former chairman and CEO of furniture maker Herman Miller as well as an author, once wrote, “The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality. The last is to say thank you. In between you become a servant and a debtor.” Jim Kouzes uses that quote to get to the heart of a leader’s responsibility—to tell the truth.

That truth begins with a look inward. In his more than thirty years of research, including collecting best practice stories for The Leadership Challenge (now in its fifth edition), Kouzes notes that nearly every story featured offers an example of someone facing a significant challenge. “One of the things that was striking about this—and not something we expected—was that every single story was about challenge, adversity, uncertainty, difficulty, and change. It wasn’t about maintaining the status quo. No one ever did their best by keeping things the same. Every situation was about changing the way things were—and often very dramatically.” Some folks climbed mountains; others started businesses; and still others rebuilt them.

Inherent in facing adversity is a willingness to look beyond the immediate problem to see possibilities over the horizon. One of Kouzes’s favorite quotes is from legendary Hollywood agent and deal maker Swifty Lazar, who said, “Sometimes I wake up in the morning and there’s nothing doing so I make something happen by lunch.” Kouzes likes to tell leaders to “Post this quote on your wall or computer screen so you can remind yourself to take initiative. Every day when lunchtime arrives if you haven’t made something happen, delay lunch.” That’s where opportunity enters.4

Leveraging Adversity

We can also view opportunity as the flip side of adversity. Doug Conant discovered this when he was named CEO of Campbell Soup Company in 2001. Although he was a veteran of the food industry, having worked for General Mills, Kraft, and Nabisco, nothing prepared him for the challenges he would face at Campbell Soup. The first eighteen months were tough. He realized that the challenges facing the company were beyond the scope of its leaders. As Conant said, “You can’t talk yourself out of something you behaved your way into. You have to behave your way out of it.”

The approach Conant implemented was methodical. Using a three-year plan, he challenged executives to develop annual operating plans and quarterly priorities. Nothing special there, but Conant insisted in the first year that such plans and priorities be reviewed by his executive team via e-mail every Friday and subsequently discussed in a Monday morning staff meeting. Attendance was mandatory. “It was a very disciplined process [focused] on getting control of the enterprise and getting it on firmer footing.”

That sounds good, but it also requires the personal commitment of those at the top. And in this regard Conant found himself doubly challenged: he was new to Campbell and he was an introvert, the quiet and reserved type. However, he realized that if he was going to turn Campbell around he would have to be highly visible. So, early in his tenure, he discussed his introversion publicly, or, as he says now, he declared himself. Specifically, he told his employees, “You are going see me standing off to the side [at some corporate event] and you may think of me as aloof and not interested in who you are and what you are doing.” But that’s not the whole story. “The reality is I’m just shy and I don’t know what to say.” Conant asked others to make conversation with him, and it worked. “It took the weight of the world off my shoulders as a leader,” he said. Admitting such shyness enabled him to focus on his job and at the same time it invited others to converse, and, more importantly, to communicate with him honestly and directly. Over time, Conant’s shyness dissipated because he had “stopped internalizing it.”

As important as a structured turnaround is, it cannot work without making changes. “I had to create a culture of creativity and accountability,” says Conant, because “99 percent of decisions made within a company are being made when [the CEO] is not in the room.” Under Conant’s tenure, Campbell expanded its soup product line to meet the needs of consumers who wanted to eat soup at work or on the go. “We were always on the lookout for new and better ways to do things,” he said. Driving the turnaround plan, as well as creative impulses, was a sense of urgency: “We had to innovate or die.” Building on that was the mantra, “the number one expectation of a leader was to inspire the trust of others.”

Not every executive was up to the task, and the company replaced more than 300 of the top 350 executives. One hundred fifty of these were hired externally, but another 150 or so were promoted from within. These folks “were dying to contribute in a more substantial way but weren’t given the opportunity,” Conant found. These executives rose to the challenge, and after three years Campbell was back on top, posting a solid performance for the next eight years of Conant’s tenure.

Making Things Happen: Three Case Studies

Creating opportunity is often a matter of looking in the right place at the right time. Consider McDonald’s big hit of 2013—the McWrap. McDonald’s is the global behemoth in fast food. Introducing new products that are extensions of existing products, be they hamburgers or chicken sandwiches, is not that difficult. Introducing a new line of food that is fresh, appealing to the health-conscious, and can be made simply, cost effectively, and quickly is another matter.

According to a Bloomberg Businessweek cover story, McDonald’s spent fourteen months working on the McWrap. Don Thompson, CEO of McDonald’s, summed up the challenge aptly when asked about the changing taste preferences of younger consumers: “We’re as vulnerable today as we always have been. Tastes have been changing.” So finding opportunity is not a nice thing to do; it’s a strategic imperative.

Failure to change may cost the company customers, and launching a product that fails can be embarrassing as well as costly. The Arch Deluxe, a hamburger launched in 1996, cost $100 million to introduce. It bombed and then disappeared. So introducing a new product can be a roll of the dice.

The idea for the McWrap was not a made-in-America story. A version of a chicken wrap first appeared in McDonald’s Poland. Unlike other fast food companies that push for homogeneity in their offerings across the world, McDonald’s has a long history of adapting its menus to suit local tastes. In a sense, it’s an extension of founder Ray Kroc’s approach to letting owner–operators develop new product ideas. The Big Mac and Egg McMuffin are two such examples.

Assembling the right ingredients at the right price point in ways that appeal to American taste buds was a long journey that began in the head chef’s test kitchen. Ingredients that made the final cut, in addition to chicken, were cucumber, cheese, sauce (squiggled, not poured), and a white flour tortilla. Time and consumers’ taste preferences will determine the product’s future, but the exercise in new product development is a solid case study of mobilizing a company to deliver what consumers might be interested in. Note the words “might be.” After all, when Henry Ford was quizzed about customer intention a century ago, he reportedly quipped, “If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they would have said, ‘A faster horse.’ ” Opportunity can be serendipitous but it must be pursued.5

While McDonald’s is seeking to respond to consumer shifts in food preference, another company is seeking to deliver on the need for zero-emission vehicles. Enter Elon Musk, a billionaire entrepreneur who has turned the electric car into a thing of desire—high desire. The Tesla electric cars are favorites of Hollywood celebrities as well as the rich and famous.

Tesla Motors, unlike other companies that make only electric cars, is profitable. One reason may be the car’s roots. It was developed by non-car guys who were more into technology than mobility, and their approach focused on battery functionality. Today, a top-end Tesla has a range of three hundred miles, more than any other electric vehicle. Quick charging is another feature—twenty minutes can replenish the battery so it’s good for another two hundred miles. Other electric models require hours of recharging. Styling is also appealing, and, unlike other carmakers, Tesla controls its retail outlets. No franchise dealers. This enables concierge-like service and innovative financing plans.

Tesla’s business does not rival that of Ford or Toyota, but it does demonstrate that savvy entrepreneurs can deliver on opportunities if they can marshal the right resources for their dreams. Elon Musk, who made his fortune as a cofounder of PayPal, is the right guy to capitalize on opportunities to deliver value to customers and profits to company coffers. His other major venture is SpaceX, a company that is pioneering privately financed space travel. In May 2012, one of his rockets docked with the International Space Station.6

One established company and one entrepreneurial start-up are demonstrating that strong leaders find opportunities where change meets need. Capitalizing on this intersection requires an ability to communicate the vision to others and to mobilize them to execute it in ways that deliver value.

Opportunities often arise from disruption. Disruption can be an effective strategy when it comes to doing something different and making it work to build a business. One example is Netflix, which has disrupted the marketplace not once but multiple times. As TV critic David Carr noted in a perceptive column for the New York Times, Netflix first disrupted video distribution by using the U.S. Post Office as its distributor of DVDs. This effort was immensely popular and the business grew.7

Then Netflix began streaming video directly to subscribers, who paid a monthly service fee that entitled them to watch as many movies or TV shows per month as they wished. Again, the business model proved successful.

The next disruption was self-inflicted. In August 2011, Netflix decided to split the businesses into two different business units, meaning customers needed to pick which service to use or pay 60 percent more to keep both. The outcry was huge and Netflix lost as many as one-third of its subscriber base. CEO Reed Hastings, who had been recognized by Fortune magazine as CEO of the Year in 2010, looked to have made a huge mistake.

But, as Forbes.com commentator Adam Hartung wrote, “CEO Hastings actually did what textbooks tell us to do—he began milking the installed, but outdated, DVD business. He did not kill it, but he began pulling profits and cash out of it to pay for building the faster growing, but lower margin, streaming business.” And it worked. The streaming business grew and the DVD business declined.8

It was now time for its third disruption—creating exclusive content for Netflix. The first major effort was the funding of twenty-six episodes of a Netflix-only series, House of Cards, a political drama starring Kevin Spacey as an ambitious politician on the make. The first thirteen episodes were launched in spring of 2013 and the response was hugely positive. The practice of releasing all new episodes at once was again disruptive and validated a trend that many viewers had already adopted—binge viewing, watching one series in large doses.

House of Cards is a bona fide hit and garnered a number of Emmy nominations. And as TV critic and media professor David Bianculli told David Carr, “It took HBO twenty-five years to get its first Emmy nomination; it took Netflix six months.”9

Netflix subsequently resurrected a network TV show, Arrested Development, that had been canceled four years earlier. It also introduced a couple of other shows of its own, including Orange Is the New Black, a drama set in a women’s prison. The content-creation model was working.

Nothing Netflix did was extraordinary per se, but by looking at what consumers wanted in terms of television watching, it was able to deliver movies and TV shows directly, first through the mail and later via the Internet. Creating its own content was the next huge step, and it shows that innovation need not be totally original; rather, it must be focused on providing something different in terms of convenience.10

Taking Opportunity to the Next Level

Successful leaders capitalize on opportunities, but they do something more. They create opportunities for others. The greatest untapped reservoir of organizational strength is purpose. That statement is a definition I have often used when I speak and write about the power of purpose. And so when I read, “The greatest untapped source of motivation is a sense of service to others,” my brain blinked Bingo!

The quote comes from a New York Times Magazine profile by Susan Dominus about the work of Adam Grant, a thirty-one-year old professor at Wharton. Grant has published a slew of peer-reviewed papers and is the author of a new book, Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success. The rest of the quote, which is Dominus’s summary of Grant’s thinking, notes that when we as employees consider our “contribution of work to other people’s lives [it has] the potential to make us more productive than thinking about ourselves.”11

Grant, who was interviewed for the article, says, “In corporate America, people do sometimes feel that the work they do isn’t meaningful. And contributing to coworkers can be a substitute for that.” Grant’s research proves his thesis. Employees are more engaged and motivated when they feel they are contributing beneficially to others.

Grant himself models this behavior. According to the New York Times Magazine, he views teaching and advising students—even those not enrolled at Wharton whom he encounters via email—as part of his job, not something extra. It does not hinder his productivity; it may indeed improve it.

Essentially, what Grant is documenting, as others have before him, is the power of altruism. As research shows, altruism may be embedded in our DNA; it sparks the impulse to give and take care of others. It certainly sparks volunteerism. People are motivated to help others because they want to, and they feel good about doing so.

In my interview with Grant for this book, he said, “Many leaders underestimate the power of operating like a giver.” It is different from charitable giving and volunteerism. “The giver mind-set is a focus on making other people better off…. There is compelling evidence that when leaders operate like givers they do better and so do their organizations.” As Grant explains, “Many employees respond to giving leaders by acting like givers themselves, which means more knowledge sharing, more creativity and innovation, and more helping and problem solving.” This is beneficial for the organization. What’s more, Grant says, “people want to work for someone who puts their interests first.” And it makes sense. When we do for others, they may be inclined to do for us. And, as Grant explains, organizations “end up building a culture where it’s harder for people to act like takers and get away with it. You end up… weeding out these zero-sum games where one employee wins at the expense of another.”

But, as Grant notes, leaders who give and give can wind up being taken advantage of. So he advises leaders to align their giving with their “organization’s values and goals… Help[ing] people who are not aligned [with company goals] is a recipe for disaster.” Therefore, you prioritize. Share your expertise where you can do the most good. That is, if you have expertise in finance, share that. If your expertise is in human resources, spread that knowledge. Finally, Grant believes that boundaries are important. Leaders can and must make time for themselves to think and reflect as a means of getting their own work done.

Practicing service is another matter, and what makes Grant’s conclusions so powerful is that he is focusing on organizations, including the corporate sector. Purposeful organizations deliver on the service equation, both internally and externally. So how can we show service in the workplace? First and foremost, consider not so much what you do but the outcome of what you do. That is, think, “What effect will doing my job well have on my coworkers?” Next, put your mind-set in place. Consider these options.

Listen, don’t judge. Frankly, this might be the toughest advice, because we often think we know what colleagues will say before they actually say it. So, rather than preemptively dismissing a comment, keep an open mind and use this flexible stance as a point of leverage for conversation. Ask an open-ended question or ask the person to expand on his comment.

Think “want to” rather than “have to.” We all have must-do tasks. Thinking of them as things you want to do to help another person perform her job better reframes the work as a matter of helping, not simply completing.

Put benefits before tasks. Look for ways to turn what you do into things that benefit your colleagues. For example, if you finish a task early, you have time to help a coworker. Or if someone is waiting on your decision, an early response helps him initiate a project earlier.

Adopt a “me-last” approach. Marine officers have a tradition of waiting till the junior ranks have been served before they eat. It makes a positive impression when you, as a senior person, defer to a subordinate. It shows that you have respect for others and a sense of humility about yourself.

Step out of the limelight. Let others get credit for a team effort when things go right. And if the reverse occurs, stand up for your team.

These suggestions are intended as thought starters. What you do is up to you, and once you let your mind think more freely you will come up with ways that you can make a difference. So let me share a story.

Once I was working with an executive who had been targeted to move up. The only problem was that at times he would rub his colleagues the wrong way. He would act impatiently, cut people off, and sometimes behave gruffly. That’s not uncommon in managers, but here’s what was different. This executive was terrific with customers. Whenever there were problems, he was the first person brought in. He was patient, attentive, and understanding, not to mention technically proficient. His behavior with customers was exactly the opposite of his behavior with colleagues.

In our initial coaching conversation, I challenged him to think of his colleagues as his customers. From the look on his face I could tell he made the connection almost instantly. And that was it. He adopted a customer-service mentality toward colleagues, which confirmed his good nature, and people responded better.

Of course, the spirit of giving back, of being of service to others, must be rooted in competence. You must prepare yourself to do your work by being educated and trained. You must do what the job entails and more when it makes a positive difference, as it often does when you see the results your work has on others.

Service is the dividend of purpose. Service validates and renews purpose in ways that make it meaningful for individuals, because it affirms their contributions and strengthens organizations by promoting engagement. By focusing on service, we create opportunities not only for others but for ourselves as well. Service opens the door to deliver on opportunity because it enables the leader to do her job—to work through others to achieve intended goals.

Opportunism: An Entrepreneur’s Story

Entrepreneurs are prime examples of opportunists. As Daniel Isenberg, business school professor and best-selling author, argues in his book Worthless, Impossible, and Stupid, innovation is not as important as finding the right opportunities.

In a chapter called “Solving Burning Problems,” Isenberg creates a word equation that I find pertinent: “Entrepreneurship = adversity + human capital.” In short, Isenberg states that problems or challenges present those who are looking to make a difference with the opportunity to create something. All it takes is the problem and some investment capital.12

One example that Isenberg profiles is Vinod Kapur, founder of Keggfarms, one of the oldest poultry breeding farms in India. After economic liberalism hit India in 1991, Kapur realized that he could avoid going head to head with global poultry producers since those producers focused on major cities. Kapur found new opportunity in rural India, where 75 percent of the population lives. This population is also extremely poor, so he would have to find a means to grow the business and at the same time help the local populace.

After years of experimentation, Keggfarms introduced the Kerbroiler, a beautifully colored bird (Indians believe white chickens are inferior) that could live on household scraps and that was aggressive enough to fend off local predators, such as dogs. It also added weight quickly and could begin laying eggs by six months. Kerbroilers reached full weight at a year and could be used for meat or kept as egg producers.

Distribution was challenging because it meant distributing perishable items in high heat throughout the rural countryside. The solution was to enlist a network of dealers who would take the one-day-old birds and distribute them to local households once the chicks had achieved a weight of three hundred grams. Each chick costs sixty cents and, because they eat household scraps, they cost nothing to maintain. They lay eggs and can eventually be sold for meat. By solving the breeding issue as well as problems with the distribution system, Keggfarms was able to bring new business opportunities to rural India.13

Entrepreneurs are more than problem solvers. They see value where others do not and they can make something out of nothing.14 Bob Lutz, when he was president of Chrysler, said that one reason Chrysler eyed American Motors was because the company was perennially short of cash but seemed able to continue to produce multiple vehicles. Lutz quipped that sooner or later he would figure out how they could make something out of nothing.

Entrepreneurs learn over time to deal with risk. After all, capitalizing on an idea is a risky venture. Gabi Meron of Given Imaging recognized this when he came across a new technology called PillCam. In essence, it’s a swallowable camera that can take pictures of the small intestine. While the obstacles to such a venture, both inside the body as well as outside it (with acceptance and FDA approval) were significant, Meron realized that if he were to bring PillCam to market he would have to think as big as the PillCam was small—that is, he would have to be revolutionary. So he stepped up development of the PillCam and submitted it to the FDA. Given Imaging also rolled out the product in three major markets (the U.S., Europe, and Japan) simultaneously. And it worked. Regulatory approval in Europe came more swiftly than it did in the U.S., so Given Imaging had a revenue stream. And since it was a “proven product” in Europe, the company was able to mitigate risk in Japan by working with local partners.15

Hidden Opportunities

While entrepreneurs get much credit, and deservedly so, for perseverance in pursuing opportunities, many successful executives find opportunities in their own organizations, if they look hard enough. Such was the case with Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips. Early in his career he was a mid-level manager working for ARCO on Alaska’s North Slope. As Lance explains, “We needed to set a new standard for North Slope Arctic developments going forward. Developments needed to be smaller and more sustainable with less environmental impact. And so we set out to create this new standard of excellence.”

The challenge was significant, but Lance and his team pursued it: “We put together a conceptual plan to develop the field and took it to ARCO management for approval. They essentially kicked me out and said, ‘We like the cost, but don’t think you can do this. There are too many technical firsts, too many things you’re trying to do at one time, and you’ll fail.’ So they sent us back to the drawing board. That was a devastating defeat for me and the team.”

But, it was not the end. While the team tried alternative plans, none seemed as effective or compelling as their original plan. Lance says, “Two months later we took the exact, identical plan back to management and said, ‘This is the way we’ve got to do it. Give us a chance to prove that we can get it done.’ They did approve the project, which put more resolve into the team. We truly believed we had the right answer, the right plan, and we turned that defeat into a victory. In fact, it successfully developed the Alpine Field, which has exceeded all expectations over the course of the last twenty years.”

Opportunities fulfilled come to those who pursue them and stick with them even when others may not see its promise of success. Leaders must view opportunity as necessary to moving an organization forward. And when an opportunity fails, a mindful leader will take lessons from the experience and apply it to the next venture.

Closing Thought: Opportunity

Opportunities come to those who seek them and are willing to work hard to make them real, even when the odds of success are formidable. Leaders are mindful of opportunities, but their approach is more than opportunistic. It is holistic. They seek to create opportunities for themselves as well as others.

Opportunities, however, are not pennies from heaven. While sometimes they are the result of serendipitous events, most often they emerge from a combination of awareness and a commitment to discipline. That is, a leader recognizes an idea’s potential and then works hard to fulfill it.

Opportunity = Need + Solution

Leadership Questions

- What new opportunities are you looking for and why?

- How well are you succeeding in this search?

- What will you do to ensure that you continue to place yourself in the path of discovering new opportunities?

Leadership Directives

- Look at the opportunities that have come your way in the past two years. How well did you capitalize on them?

- If you did not take advantage of these opportunities, why not? What held you back? What can you do differently to ensure that new opportunities arise?

- An opportunity may come in the form of an invitation to try something new, or it may be as substantial as a new career possibility. It is essential that you clarify each opportunity and consider its merits for you. For example, you may be ready to take on a new assignment at work, but not change careers. On the other hand, you may be ready to go back to school and do something completely different. Clarify your options before you make up your mind.