5

Engagement

Let no one ever come to you without leaving better and happier.

MOTHER TERESA

A Better Way for People to Work Together

Rich Sheridan was looking to do something differently in software design. He had become frustrated by traditional methods, and in 1999 he read Extreme Programming by Kent Beck. He’d also seen a documentary on the process the design firm IDEO used to redesign a shopping cart on the ABC show Nightline. Once he became a vice president in an established company, he was in a position to implement his ideas: “And within six months I had transformed the R and D team, which affected the entire organization, and I got two years to run it and perfect it.

“Then in 2001 the Internet bubble burst and for the first time in my career I was out of work. The California company that had bought us shuttered every remote office they had, including our Ann Arbor operation. And now here I was having achieved my goal. I had this great organization. It was rocking and rolling and now it was all taken away from me. So that was the next level of adversity. I went home to my wife and I said, ‘Honey, I got—lost my job today.’ And she said, ‘You’re unemployed?’ I said, ‘No, I’m an entrepreneur now.’ ”

As Rich explains, he knew that what he had built for his previous company was a concept for software development that would be transferable to another company, one he would develop with his partner. “As my father would always say,” notes Sheridan, “‘Sometimes things that look like the worst turn out to be the best.’ ”

Introverts Know How to Engage Others

In 2006 Adam Grant, a management professor at the Wharton School, was a graduate student in organizational psychology. He was asked by his mentor, Brian Little, if he would be interested in meeting with Susan Cain, a lawyer-turned-author who was writing a book on the power of introverts. As Grant says, “[Cain and I] had what was supposed to be a thirty-minute meeting and it turned into about three hours. I was just totally fascinated by what she was studying. As I talked with her, I realized that there was a huge imbalance in research on introverts and extroverts, in that we had all this evidence that extroverts were more likely to be selected for leadership roles, that we look at extroverts and we tend to assume they’re charismatic, they’re gregarious, they’re socially skilled, lots of things that are useful for leaders. Also, extroverts are much more attracted to leadership roles, because it’s a situation where you experience a lot of stimulation, you get to be the center of attention, [and there are] lots of opportunities to be assertive.

“There are also studies showing that people rated extroverts as better leaders. But I couldn’t find a single study, as Susan went through her list of questions for me, that actually linked extroverted leadership with better performance. And there was a moment where I think in a lot of cases I would have just said, ‘Wow, that’s a big gap, somebody ought to study that.’

“Susan got me so fired up. She was so eloquent and so curious and so thoughtful about this topic that I decided I was gonna start digging around to see if there was an opportunity to study that and never would have done it had Brian not put Susan on my radar.”

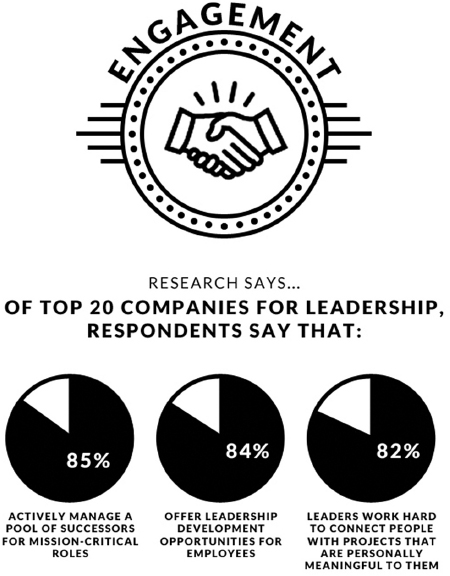

SOURECE: 2013 BEST COMPANIES FOR LEADERSHIP HAY GROUP1

Engagement. Persons with moxie seek to engage with the wider community around them. They are focused on making a positive difference in their teams and in their organizations.

Dolly Parton

The thing that resonates most with me about Dolly Parton is heart. You hear it in her songs and she acts on it in her life.

While some might be distracted by her over-the-top looks—big hair, big smile, and big bosom—it is her voice that attracts the most attention. It is at once soulful and playful. It radiates joy as well as sorrow. Most of all, it registers sincerity, and for that reason she has forged a relationship with her fans that spans generations.

Few would have predicted that a woman, one of twelve children, from humble origins in Sevierville, Tennessee, would rise to such prominence as a singer–songwriter, selling more than 100 million records. Her hardscrabble beginnings, coupled with her love of family, steeled her determination to pursue her craft. She was not only singing, but also writing songs as a youngster. Parton turned professional at age ten and appeared on local radio and television in Knoxville. As a young teen, she made her first appearance on country music’s (then) biggest stage–the Grand Ole Opry. After graduating from high school, she moved to Nashville.

By age twenty-one she was appearing regularly on TV’s The Porter Wagoner Show, singing duets with Wagoner. She had a string of country music hits and won the Country Music Award for female vocalist in 1975 and 1976. After that came more hits, but the wider appeal did not deter Parton from going back to her roots in gospel as well as bluegrass.

Essence of Dolly

To me, her song “Better Get to Livin’ ” offers insights that every leader ought to keep at the ready. That song, the lead track of her 2008 album Backwoods Barbie, allows Parton, the Oprah of Appalachia, to reveal the secret of her long career—“living, giving, forgiving, and some lovin’.” Not only do these words make good sense for country music enthusiasts, they make sense for leaders. Let’s take them one at a time.

Living. Leaders need to be mindful of their situation and the situations of those they lead. They are aware of the impact their actions have on others and they seek to do what is best for the organization.

Giving. Leaders give of themselves so others can succeed. That means you spend time coaching and developing your people. Provide them with guidance to help them build upon their strengths, overcome their shortcomings, and give them a shoulder to cry on when times are tough.

Forgiving. People make mistakes. If they acknowledge it and seek to make amends, move forward. Get over it. A leader cannot afford grudges; it rubs off negatively on others and drains energy from the team.

Loving. Apply this to your work. Have a passion for what you do; it will inspire the entire team. A leader who enjoys her work and the people with whom she works is one who encourages people to follow her lead.

There are a few other words that Parton uses in this song that also apply to leadership behavior. Among them are knowing, understanding your values; shining, standing up for yourself; and showing, letting others know you care. And there is another word Parton uses—healing. Leaders must exert themselves to bring people together. Rifts need to be breached, wounds bound, and feelings assuaged. All of these are leadership responsibilities.

Success came early for Parton, but not without some hardship and sacrifice. All of her trials, tribulations, and joys are reflected in her music. Not only does she play and sing, she writes much of her own material. She has created a business enterprise worth hundreds of millions and yet is not without ironic humor about herself. She says, “It takes a lot of money to look this cheap.” With her “glad to know ya” smile and country soprano voice, Dolly Parton knows her audience, and time and again she delivers what they want to hear. The woman knows her heart and herself.

Wider Appeal

Success in music led Parton to Hollywood. She made her film debut in the 1980 movie about savvy secretaries called 9 to 5, for which she got an Academy Award nomination. Three decades later she penned music and lyrics for a musical version of 9 to 5 that played in Los Angeles and later on Broadway.

Her major entrepreneurial effort is Dollywood, a theme park, which opened in 1986 and is located in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. Not surprisingly, Parton’s financial advisors told her not to do the project. She told them, “Well, I’m gonna do it anyway, because I know it’s the right thing to do in my gut.” The park has thrived, and in 2013 she announced a ten-year $300 million expansion of the facility.

One interest that radiates from Parton’s heart is her reading program. For the past two decades, Parton has been giving books to children as a means of fostering literacy. She founded Imagination Library and, as she said on PBS’s NewsHour, “Everywhere I go, the kids call me ‘Book Lady.’ ” As Parton explains, “It really … started out as a very personal thing for me … originally meant for the folks in my home county … There were not books in our house growing up.” Her father was illiterate, which Parton describes as a “crippling thing for him.” Today, her Dollywood Foundation sends books to kids in 1,700 communities throughout the United States, Canada, and England.

“The older I get the more appreciative I seem to be of the book lady title,” says Parton. “It makes me feel more like a legitimate person, not just a singer or entertainer. But it makes me feel like I have done something good with my life and with my success.” You hear in those words the little girl born into poverty who rose above it with her talent, her commitment to her art, and her genuine engagement with others. In 2006 Parton was recognized by the Kennedy Center for her contribution to the arts, a rare tribute for a performer with country roots.

Dolly Parton’s life as reflected through her art and in her actions is a shining example of what it means to live with heart. She reflects the essence of engagement, of putting yourself into your work. Leaders must foster commitment from others but first must be committed themselves. Dolly Parton shows us how that can happen.2

*****

Leaders do not work in isolation. They work with others in order to bring their ideas, their dreams, and their aspirations to fruition. To do this they must engage with others. The engagement can be as simple as one-on-one conversations that lead to relationships, or it can be engagement with groups, teams, or entire organizations. Engagement is an essential part of extending the leadership self in order to make a positive difference. It is also the ability to keep those who follow your lead focused on what it takes to turn goals into reality.

In this chapter my approach will be to tell the story of engagement from several perspectives. Here you’ll encounter multiple models, from both the profit and nonprofit sectors. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to engagement, but there is a fundamental principle to which all highly engaged workplaces adhere. It is this: there is dignity in work, and when we treat workers with dignity they become contributors to results as well as to success.

Jim Haudan, CEO of Root, a visionary strategy and learning company, says his company “Is driven by the cause that people are not bringing the best version of themselves to the workplace. [We] want people to be engaged, but for some reason fear permeates the workplace.” Strategy is important but what truly matters, according to Haudan, is “when people come together with aspirations to build something that doesn’t exist.” The challenge is to focus on purpose, or, as Haudan says, move from the “unconscious to the conscious. [This] invigorates the power of human beings to make a difference.”

Doing this is Haudan’s life’s work. Originally an educator, he earned an MBA and then came to Root, where he combines his passion for teaching and learning with running a business. Now as CEO, his passion is “to get people off the bench and in the game of their work life so they can have two things: a sense of meaning and purpose from being part of something bigger than themselves, and [pride] in the results that can be achieved together” with other like-minded people. That is engagement in a nutshell.

Engaging with Purpose

The question is, how do we engage with purpose? First, leaders must enable others to recognize purpose on two levels—organizationally and personally. Leaders must instill purpose by linking what a company does (its mission) to what it wants to become (its vision). They do this through their communications and their actions. They leverage purpose as the why of work, that is, why do we do what we do?

Then, as Haudan explains, it is up to leaders to give people a chance to buy in. In a recent workshop Haudan conducted with Robert Quinn, a professor of organizational development at the University of Michigan, attendees had the opportunity to link their personal stories to the story of their organization. It resonated with them on a visceral level much more than on a strategic level. The lesson is that strategy is important, but it is not something that people connect to personally. Purpose, however, is something to which people relate for one simple reason. It gives meaning to what they do. As Haudan says, it’s that “larger than themselves” connection we all crave.

Part of engaging the workforce involves providing purpose, but that purpose must be put into a context of making things happen. One model for dynamism is agility. As defined by Thomas Williams, Christopher Worley, and Edward Lawler III, in an article for strategy+business, “Agility is not just the ability to change. It is a cultivated capability that enables an organization to respond in a timely, effective, and sustainable way when changing circumstances require it.” According to the authors, agility is confirmed by four routines:

- Strategizing dynamically—knowing what you do and why it matters

- Perceiving environmental change—sensing that change is occurring and gauging its significance

- Testing responses—assessing risk and learning from what has been happening

- Implementing change—managing change to work for the organization

As Williams et al note, companies that possess the “agility factor” outperform their peers over the long term. Examples of such companies include ExxonMobil, Capital One, DaVita HealthCare Partners, and the Gap. The challenge for leaders is not to teach another business model, but to encourage managers and employees to make change work for them rather than against them. That emerges from having a shared purpose that everyone understands.3

As I wrote in my book, Lead with Purpose, when people know what is expected of them, they can deliver. Better yet, when they help contribute to those expectations, they may do even better. This means that managers need to make certain that people know that their place is to voice ideas when they have them, and—when appropriate and with approval—put them into gear. Such a culture of engagement is well-known at companies like 3M and Google, where employees are encouraged to devote time to pet projects that complement the mission of their teams as well as their organizations.4

Engagement: Setting the Foundation

For Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, engagement builds on purpose. Thus, all employees must know where the organization is headed. Lance shares his management philosophy with employees. It’s a leadership concept he calls the SAM model: “The S stands for set directions. The A is align, and the M is motivate.” As Lance explains, “When you can set a direction that’s simple and inspiring—even differential—it really does motivate people, and they understand the strategic objectives of what you’re trying to accomplish, where you’re trying to go, and what they should expect from their leadership team.”

As Lance notes, “It’s absolutely critical that people understand the direction you’re trying to go and leadership has to set the forward course, describe how the employees can connect and how their goals are contributing. Then you must energize stakeholders to get it done. We work really hard on alignment, and then spend a lot of time on motivation to make sure everybody is pulling the oars in the same direction.”

Strategic intentions are built upon “a core set of values that set the tone for our direction and the behaviors needed,” Lance said. “At ConocoPhillips, core values are expressed by the acronym SPIRIT. It stands for Safety, People, Innovation, Responsibility, Integrity, and Teamwork. The SPIRIT values summarize our character. Everything that we do reflects our SPIRIT values, both in our operations and in our interactions with the communities in which we operate. While we’re fairly understated in how we approach things, our SPIRIT values always shine through.”

Engagement Begins with Listening

Fernando Aguirre, former CEO of Chiquita Brands, believes that engagement relies upon two important factors: “One is to communicate all the time; and two is to find objectives that are common and that employees can make them their own.” When Aguirre joined Chiquita as CEO, he spent his first ninety days as chairman and CEO “going on a listen and learn campaign and told employees that [he] was not going to make any major decisions in those first ninety days.” Aguirre processed what he learned by writing about and reporting his findings to various business units.

The listening and learning continued throughout his tenure at Chiquita. Aguirre says, “I was very visible as the CEO of the company, and by that I mean I was walking around. I would do town hall meetings constantly. I was traveling anywhere between 60 and 80 percent of my time, depending on the time of the year. But anytime I would visit any of our operations, I would hold town hall meetings with every employee that was in the building, no matter what level, no matter if they had joined the day before or if they had been in the company thirty-five years. And I would talk a little bit about results. I would talk a little bit about what we were doing strategically, and then I would answer their questions. And I would spend anywhere between an hour and sometimes an hour and a half just talking to employees about what was going on in the operations.”

Aguirre extended his town hall concept globally. He held quarterly review sessions that were broadcast throughout the company. He says, “I started every single town hall (or quarterly) meeting by reminding folks that the most important part of this session is going to be your questions.” Employees were notified in advance to prepare questions.

Aguirre also leveraged his message to connect the corporate mission with the work that employees were doing. “You need to figure out objectives that are common for the majority of the people.” As Aguirre explains, such commonality ensures that everyone is focused on the same goals, but it also enables managers to implement their own ideas in order to achieve the best results for their business units. In this way, Aguirre says it is employee “ideas that end up influencing the work.”

Engagement: The Leader’s Responsibility

Engagement is a process of setting the right example. People are always watching the leader. Her behavior becomes the yardstick by which others judge a leader. One way a leader can begin to set the right example is to be accessible and available.

As General John Allen explains, “The one area which I always felt was very important to my troops was that I was always present. I was always accessible. You have to stay up—you can’t have bad days as a commander. You can’t—while you may be under extreme pressure—show the pressure. And while there were a number of occasions where the enormity of what we were doing was really pressing in hard, if the commander is able to lead from the front—morally, spiritually, physically as well—but also tactically and operationally, the unit will hold together.”

Keeping focused on the task at hand in trying circumstances means taking care of yourself. As Allen says, “One of the things that helped me a great deal is my endurance [which] is actually pretty good. It comes again from the ability to intrinsically motivate myself, and is based on my physical conditioning. [W]hen you’re in good physical condition then you have the capacity to endure a great deal. You are less prone to uncertainty or less prone to the onset of fear. Your decisiveness is enhanced by your endurance.”

That kind of fitness, certainly in a combat situation, gives those who follow the leader a kind of reassurance. “I’d be the last guy standing in a crisis and [our soldiers] took a lot of heart in that,” says Allen. “They felt a substantial amount of comfort that, no matter how hard things got, the chances were pretty good that while I might be bent by the process it wasn’t going to break me. That gave them a lot of confidence.”

Endurance, however, cannot and should not be an excuse for trying to act superhuman. “Commanders and leaders need to take inventory of themselves—what are the personal conditions under which I’m operating right now,” says Allen. “There were many occasions where I was simply exhausted, and exhausted day after day after day and one more crisis, the wash of one more crisis over me, I wondered whether I could take it or not.” Honesty with oneself is essential to being able to engage with others. And that would sometimes means taking a nap. “If I could catch five, ten, or fifteen minutes in between events I’d lay down quickly and just close my eyes and get ten or fifteen minutes. We called it a ‘combat nap.’ But I’d fortify myself. I’d take inventory of where I am physically and spiritually and then immediately go about the business of ensuring that I was reacting to the crisis in a manner that calmed the command, not excited the command.”

It’s a leader’s job to control his reaction to the situation or the crisis. “The last thing you need is for people to become excited in a crisis in a manner that compromises or in some way complicates decision making and the ability to react,” says Allen. “You want to take the energy out of the crisis if you can, and insert the commander’s calm. And in being calm in a crisis, it just permits everyone to face the issues and not face the energy, and that’s really what you want to try to do.”

John Allen’s leadership behavior is a first-rate example of how a leader’s behavior affects engagement. This is a topic that professor and author Jim Kouzes has studied. In analyzing data from the Leadership Practices Inventory, the leadership assessment that he codeveloped with Barry Posner, Kouzes found that the leader’s behavior is the single biggest factor in determining workforce engagement. As Kouzes explains, “We can’t predict engagement from knowing whether the workforce is highly educated or never attended college. We can’t predict engagement based on whether the person is in marketing, finance, sales, or operations. We can’t predict engagement if the constituents are male or female. We can’t predict engagement based on any of these variables. Demographics accounts for less than 1 percent of the explained variance. But we can predict engagement based on how a leader behaves.”

When it comes to engagement Kouzes says, “Leaders increase engagement at work when they are clear about their own personal values and when they make sure that people are aligned with shared values in the organization. Leaders increase engagement when they are also clear about where the team, business unit, or organization is headed, about the vision of the future. Leaders have to envision an uplifting and ennobling future and enlist others in it. We call that ‘inspire a shared vision.’ ”

Kouzes also says that leaders increase engagement and performance when they “challenge the process, enable others to act, and encourage the heart.” He and his coauthor find that when leaders more frequently demonstrate the Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership, as they refer to it, workforce engagement and performance go up. “There is no doubt,” he says, “that exemplary leadership matters. The question is not, ‘Do leaders make a difference?’ They clearly do. The more important question is, ‘How do leaders make a positive difference?’ ”

Engagement As Persuasion

Engagement begins with one-to-one contact. As basic as that sounds—and it is basic—too many leaders overlook it. One way to get a handle on engagement is to view it as an ongoing conversation with employees. And vital to engaging the interest of another is persuasion. For instance, Lyndon Johnson used his persuasion skills to help hold the nation together in the wake of the Kennedy assassination.

It is not simply a matter of talking a good game—though that helps—it really depends upon the ability to connect with other individuals. Masterful persuaders are those who can get inside the minds of the people they are seeking to persuade as a means of using that understanding to bring them around to their way of thinking.

As depicted in The Passage of Power, Volume 4 of Robert Caro’s towering biography of the former president, Lyndon Johnson was one such master of persuasion. He put his skills into high gear when he was thrust into the presidency at the “crack of a rifle,” as contemporaries put it.5 One example of his persuasive skills was his ability to get Richard Russell to serve on the Warren Commission investigating the Kennedy assassination. Although Russell was elderly and frail, he was much respected. Unfortunately, Russell disliked Chief Justice Earl Warren, who was heading the commission. The conversation between Johnson and Russell, recorded by the White House taping system and dissected in Caro’s retelling, reveals the art of persuasion by an acknowledged master. Analysis of the recordings yields several useful strategies:

Do your homework. Johnson knew that Russell’s participation on the committee would imbue it with a sense of dignity. At the same time, his loyalty to Johnson ensured that he would also be Johnson’s eyes and ears, something that was vital to Johnson, who needed to be aware of the commission’s doings.

Get inside the other person’s head. Knowing what motivates the person you are seeking to persuade is essential. Russell was first and foremost a patriot, and Johnson leveraged that conviction by saying that Russell’s participation on the committee was a national duty he could not ignore.

Focus your communication on the motivational factor. Tailor your communication to delivering what the other person is seeking: attention, recognition, or promotion. Johnson did this by playing on Russell’s commitment to national service and his desire to help his former protégé, Johnson.

Highlight the importance of the other person. Make the person you are seeking to persuade acutely aware of how important she is to you and to the organization. Make her feel important in a constructive way. Johnson flattered Russell endlessly and it worked because Russell took pride in the younger man’s praise.

Follow up. Never consider the persuasion complete until you have achieved your goal. You want the other person to support you and your project. Continue to employ the above steps to facilitate this. Johnson remained in close contact with Russell throughout his presidency and sought his counsel often.

Make no mistake, there may be elements of manipulation in persuasion. Johnson certainly manipulated Russell and a good many others. But effective persuaders are more than manipulators; they have core values that give them a foundation upon which to build their case. For Johnson, it was the fate of the republic. For executives it should be the fate of the individuals they lead.

Persuasion is a powerful tool that leaders use to bring people together for a common cause. Focusing your attention on it will enable you to reach the people you need, to bring them together for the good of the organization. Looked at from an organizational perspective, persuasion is a tool to stimulate engagement.

Mindful Engagement

While engagement is nurtured one on one, it will not work if the leader herself is not committed to the process. As Jim Haudan says, “The biggest mistake I hear leaders [make] is that they get up and they say … that the trains have left the station, the boats are sailing for a new destination, we’re getting the right people on the right seats of the bus.” According to Haudan, that kind of rhetoric does just the opposite: “People stay away from trains, boats, and company buses.” Put another way, according to Haudan, too many managers view engagement as what you do to people rather than for them.

You need to make the personal connection. Haudan uses the analogy of successful comedians. He notes that Bill Cosby can have an audience of three thousand follow him after twelve minutes of watching him on stage. By contrast there are leaders with whom employees have worked for twelve years and they wouldn’t cross the street for them. Why? Because according to Haudan, these executives “really don’t understand the role of empathy” and the importance that empathy plays in validating an individual’s sense of self-worth.

Personal connection to the work is critical. And that only occurs when leaders and followers are on the same wavelength. When they are both connected to the work and to the purpose, exciting things can happen.

Connect the Dots

The way to build upon personal connections is to “connect the dots.” That is, the leader must relate the work of individuals to the collective work of the team and ultimately the organization. Adam Grant of Wharton notes that in organizations, particularly large ones, those who work in functional groups often do not see how their work links to the whole of the enterprise. His research shows that when you “[p]ut people in contact with the people who benefit from their efforts, you get a dramatic increase in motivation, performance, and productivity…. Engagement comes from recognizing that your work is meaningful and other people really value and appreciate it.”

One example Grant cites is something that occurs at John Deere, the maker of farm equipment. The company stages something it calls the Golden Key ceremony, and it is for farmers and family members who are buying their first new tractor. Employees who helped assemble that tractor are invited to the ceremony to see the farmer take possession of the tractor by starting it for the first time. As Grant says, “The look of joy on the faces of the farmer and his family really brings the work to life.” Employees know that such a tractor will be used in agriculture, so they take pride in the fact, says Grant, that “[t]hey are feeding a family and then all of the people” who will benefit from the farmer’s labors. Chester Elton cites the example of Novartis Oncology. At an event inaugurating a new facility, leaders asked employees to sign their names on white tiles stating their dreams for the future of their function. One employee put it best when he wrote that his hope was to eradicate cancer and thereby abolish the need for their work. The white tiles were then turned into a sculpture and placed in the quad area where everyone could see it. There it stands as a testimony to the power of linking work to dreams and ultimately saving lives.

In medicine it is easy to link purpose to work, but what about a restaurant chain that sells steak and beer? As Elton told me, Texas Roadhouse has created Andy’s Outreach, an employee assistance fund to which employees contribute and which the company matches. The funds are dispensed to employees in need. They even sell T-shirts promoting the cause. And taking the notion one step further, there is a Texas Roadhouse in Logan, Utah, that donates all profits, totaling more than $1 million a year, to the cause.

Philanthropy can be a key tool of engagement, as long as individual employees contribute willingly. A good example is The Cellular Connection (TCC), Verizon’s largest premium retailer, with stores in more than thirty states. Headquartered in Carmel, Indiana, TCC has some nine hundred stores in thirty-four states. Scott Moorehead, president and CEO, believes in the philosophy of doing good by doing well.

“You have to take a step back and look what your values are,” Moorehead said in a recent interview. “Then you can build your culture around that. Trying to force a culture that doesn’t exist from a value perspective is impossible.” As Moorehead says, “You have to build the culture you believe in, making it the first thing you filter all your decisions through.”6

“When you put it together—customers matter, employees matter,” says Moorehead. His original goal—and constant commitment—is “make a company where people want to come to work.” One way to build on this commitment is to involve employees in giving back to the community.7

Such philosophy manifests itself in what TCC calls the “Culture of Good.” The operating principle is giving back to others as a means of creating a workplace where employees are engaged in their work as well as engaged in their community. Each year the stores give away back-to-school backpacks for kids, and each store is encouraged to reach out to its local community to participate in charitable activities, either by making a donation or having associates donate their time. TCC employees have two paid days that they can use to participate in charitable activities.8

There is a sense of optimism that emerges from engagement with stakeholders, especially employees. While organizations foster optimism through their activities, leaders deliver it through actions. “Fundamentally,” says Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, “I believe that people want to follow leaders who make them feel hopeful and take a positive view of the world. Optimism seems in short supply these days. So leaders who can bring people up—not bring them down—are just more inspiring to be around.”

Engage with Your Presence

The way a leader engages people naturally comes down to an ability to hone her own behavior, or her presence. While the baseline for engagement must be the power of an idea, such as a cause or a goal, the leader must communicate individually and authentically.

One example might be a musical conductor. In a delightful essay for the Wall Street Journal, Christopher Seaman delineates the ways that conductors can physically engage the musicians in an orchestra. The first is with the baton, typically held in the right hand, though there are lefties on the podium. The baton sets the tempo but is also a measure of expressiveness. The free hand either echoes the movement of the baton or underscores the music. For example, as Seaman writes, “a stroking cat” motion connotes sustained notes; a “chopping” motion does the opposite, calling for short, quick notes.

It is with the eyes that conductors truly connect. Arturo Toscanini, the great interpreter of Italian opera as well as Beethoven, had eyes that one conductor said could communicate the message without words. On a more human level, notes Seaman, a conductor’s eyes radiate connection: “It gives individual players a strong sense of involvement.” And if the conductor does not look their way, they tune him out and focus on their own interpretation.

If these techniques fail, the conductor can always fall back on his temper, letting flow with a volcano of insults designed to humiliate individuals and terrorize the entire orchestra. In truth, such displays of temper are more likely for show, and these days few musicians would pay much attention. They are professionals and want to be treated as such. So when faced with a conductor they do not respect, they do what all employees (or followers) do: pay him no mind.

But even with conducting there is the unknown, writes Seaman. “Conducting … is a very mysterious art,” said conductor Carlo Maria Giulini. “I have no idea what I do up there.” Fortunately, the musicians in the orchestra do, because Giulini, along with other great conductors, was known for his ability to bring a musical score to life, and more importantly, to breathe a spirit into it, creating great moments in music.9

Engagement, then, can be part physical. While a boss may not have a baton—or at least we hope not—she can use her presence as her instrument. That is, she makes time to be physically present. Picture an engaged school principal. She stands at the entrance of the school and greets students by name. I once watched a college president walk the hallways of his university, seemingly recognizing each and every person—student or faculty member—he saw. Watching him weave through a crowd was nearly magical, but it was also time-consuming. It took him three times as long to cross a room because he was connecting with so many people.

Time-consuming, sure, but it’s a good use of time, because the leader is investing himself in the life of the organization. Physical presence is essential and lets people know they matter. Manifesting presence in one location is demanding, but global leaders face an even more daunting task, because the people they lead are scattered across continents. Leaders I know who have mastered engaging with a global workforce do it through electronic media, including video, and they also carve out time to visit employees wherever they are located.

While physical presence nurtures engagement, it is purpose—why we do what we do—that sustains it. And effective leaders use the power of purpose—getting things done to achieve intended results—to truly bring people together. And for that we can look to the example of an organization that has been around since the seventeenth century.

How the Royal Navy Keeps Itself Current

Engagement on a broad scale must be rooted in the values of the institution. A great example is set by Great Britain’s Royal Navy. “Those who cannot remember the past,” wrote philosopher George Santayana, “are condemned to repeat it.” But, all too often, knowledge of institutional history can trap an organization in the status quo and mire it in mediocrity. And that is why long-standing institutions are finding ways to reinvigorate themselves while drawing strength from their legacies.

One such organization is Britain’s Royal Navy. According to Andrew St. George, a management professor and author of Royal Navy Way of Leadership, this four-hundred-year-old institution keeps itself up-to-date by blending heritage with a responsibility to lead in the moment when duty calls.

An example of this lesson is a memorandum that Admiral Horatio Nelson wrote to captains of the ships in his armada shortly before the Battle of Trafalgar. While the memorandum contains plans for the battle, it also contains two admonitions: the first is, be prepared for the unexpected. As Nelson writes, “Something must be left to chance,” since havoc rules in battle. The second is that captains are challenged to keep to the line, but should they become separated, Nelson adds encouragingly, “No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy.” As St. George notes, a senior officer in today’s Royal Navy carries a laminated copy of Nelson’s memorandum.

The Royal Navy nurtures its tradition through its culture. “The power of the Royal Navy approach is to focus on what individuals actually did in situations big and small,” as St. George notes in an article for the McKinsey Quarterly, “thereby providing inspiration for new challenges while acknowledging that the nature of those challenges and leaders’ responsibilities to them are an ever-changing, never ending story.”

The Royal Navy drives its culture through engagement that focuses on morale, keeping sailors and marines in good cheer, which it fosters in games, in the mess, and in expeditionary exercises off the ship. In other words, it’s one thing to talk a good game, but you have to instill pride through action and activity. And it works.

In the debrief to a serious flooding accident, the official inquiry report noted that “ ‘morale remained high’ throughout … and that ‘teams remained cheerful and enthusiastic’ … [and] ‘sailors commented that the presence, leadership, and good humor of senior officers gave reassurance and confidence that the ship would survive.’ ”

What the Royal Navy does is not unique. I would argue that the U.S. Marines foster the same kind of institutional reverence balanced by the need to act independently while caring for fellow marines first and always. The question for those of us in the corporate sector is this: What can I do to foster this kind of balance? Let me offer three suggestions based on my observations in working with successful organizations.

- Revere the past, but do not be prisoner to it. The challenge is to make your history work for you while making it crystal clear what each person must do to continue the mission. Tradition is preserved, but processes and procedures change. Allow employees to make changes that complement changing needs yet respect the values of the organization. That is, the phrase “It’s the way we’ve always done it” must not become policy if needs and expectations change.

- Tell individual stories. Organizations accomplish nothing; it’s the people in them who do the work. Allow people to talk about what they have done and why they did it. Hold “lessons learned” sessions after every major initiative. Invite employees to talk about what they would have done the same or differently. Use failure as a “teachable moment,” not an attempt to shame or embarrass.

- Focus on engagement. People do not work for institutions per se; they work with people. A leader’s responsibility is to link the work of the individual employee to the mission of the organization. Demonstrate how the individual’s work complements the team achievement. Hold people accountable for the good as well as the bad. Be liberal with good cheer and find ways to reward accomplishments.

It’s no surprise that these are tenets borrowed from the Royal Navy, but you don’t have to put on a uniform and swear allegiance to the queen to put them into practice. These principles apply to all types of organizations, including start-ups. Your history may be measured in decades rather than centuries, but in time you do accumulate experience. Very often the failures, if you pay attention closely, can be turned into lessons that will benefit the team and your customers if you make the adjustments and continue to improve.10

Make history work for you, not against you, and when you do, your legacy will be one that people integrate into their own future. Just as the Royal Navy has done for four centuries! History reinforces purpose.

Managing Without Bosses

Stimulating engagement can come from a fundamental reimagining of the way work gets done. This is an approach adopted by Morning Star Company, the largest tomato processing company in the world, headquartered in Woodland, California. As profiled by management expert and author Gary Hamel, Morning Star is a place where bosses do not exist, corporate funds are spent by employees, no one has a title, and compensation is peer reviewed.

At Morning Star, employees are expected to be responsible for what they do to get the work done. As Hamel notes, they “[m]ake the mission the boss.” In this way, people are focused on the task as well as on how that task complements the organization as a whole. According to Hamel there are six distinct advantages to the “management-free workplace.”

- More initiative. By defining work as the mission, people have the “authority to act.” And they are recognized for what they do, too. People are engaged in the work.

- More expertise. Quality is everyone’s responsibility. “Experts aren’t managers … they’re people doing the work.” In this way, expertise is applied where it matters most—where the work is done. (This is a fundamental concept behind gemba, a Japanese management technique in which value is derived from the workplace.)

- More flexibility. Structure at Morning Star is like cloud formations that come and go. In other words, you apply the structure you need to do the job rather than have the job serve the structure, as it does in most organizations.

- More collegiality. Without rank, or much of it, people feel freer to work better together. They collaborate to get the work done without looking to score points to advance their careers.

- Better judgment. With work as the mission, the job comes first. Thinking about what the job is and how you can best do it enables people to make decisions that benefit the workflow. And Morning Star educates its workforce by providing them with courses in negotiation and financial analysis.

- More loyalty. If you like thinking and doing for yourself in order to get the work done, Morning Star is a great place to work. People stick around. This even applies to seasonal workers who come to pick tomatoes.

Of course, the Morning Star approach is not for everyone. As Hamel notes, this self-management model presents difficulties. It takes time for people to fit in, and not everyone can adjust. Accountability can be an issue, as is an upward career path. What is applicable, however, is the possibility that work can be approached differently and employees can have more say in what they do in their jobs.11

Boss-less organizations can work well when the work is defined and execution is prized. A well-trained workforce can deliver on its objectives without constant supervision. But when creativity is needed, there is a need for a boss to create conditions where innovation can flourish. Such is the case with Menlo Innovations.

Fostering Engagement

At Menlo Innovations, employees work in an open-plan workplace. “No walls, offices, cubes, or doors. We work shoulder to shoulder,” says CEO Rich Sheridan. “We all work in one environment that isn’t spread out all over the planet. And we just think that’s really important. We think that somewhere along the way we’ve lost our way as a society, when we think we can take human teams and spread them over multiple geographies and expect them to perform as well or as effectively as teams that are all sharing the same space together.” Sheridan details his approach in his book, Joy, Inc.: How We Built a Workplace People Love.12

Menlo Innovations version of teamwork is the same kind of teamwork you see with sports teams. As Sheridan said in our interview, “They’re on the field together. They’re shoulder to shoulder … I don’t think you get a team in the truest sense of the word until you’ve spent time together. And we’ve just chosen a different path because of our shared belief system.”

This openness has the virtue of building esprit de corps, but it’s not easy to keep running day to day, month to month. “Every day at Menlo, human beings walk in the door,” says Sheridan. “They’ve got stuff going on at home. They’ve got stuff going on with their parents. They’ve got stuff going on with their children. They’ve got stuff going on with their friends. They’ve got stuff going on in their personal life, maybe with their health. All those things, as much as we’d like to believe get left at the door, don’t. They’re human beings. They can’t possibly leave those things behind.”

It falls to individuals to step up and resolve issues that threaten workplace harmony. Not everyone can do it, but over the years a culture has been established.

Engagement As Commitment

One element of engagement that many organizations overlook is commitment. Jim Haudan, CEO of Root, believes firmly that employees feel more engaged when the workplace is a place where they feel a sense of belonging. In part, this concept is derived from Haudan’s approach of viewing employees as customers. Adopting this mind-set shifts the balance from what we do to an employee to what we can do for them. Making the personal connection between the employee and the work is vital to engagement, but more importantly, it creates a bond between the employee and the enterprise. Once an employee feels connected, she will go the extra mile to achieve intended results.

At Root, management fosters commitment in a variety of ways. One method is borrowed from something that Haudan witnessed at a ceremony at Lourdes University in Ohio. Freshmen at the school are given a ceramic medallion. When they graduate, they give the medallion to the person at the school who helped them the most. Haudan adapted that concept to recognize employees. Employees were given a tree and then asked to give that tree to the person who had meant the most to him and helped him feel part of the Root organization.

The team at Menlo Innovations does something similar. Sheridan says, “We have group sessions, quarterly meetings, to talk about the business, or lunch and learn around some concept that we’re working on. And quite frankly, there are times when what we discuss is difficult, [when there is] some aspect of the team we want to make improvements to and we’re talking about it. You can start to see that some people are bristling a little bit because they think it should go one way and other people are bristling another way because they think it should go their way.”

It is important not to let the meeting end on a down note, so Menlo has adopted a practice that Zingerman’s, one of the world’s premier food companies (also headquartered in Ann Arbor), uses. It’s called “Appreciates.” As Sheridan says, “It’s like a popcorn type of commentary at the end where somebody will say, ‘You know what? I really appreciate that despite the fact that we were talking through some very difficult concepts that everybody here was willing to raise their voice and let it be known what’s on their mind.’ And somebody else will say, ‘I really appreciate when my colleague shared with us how she was feeling when this happened.’ And somebody else says, ‘I really appreciate that we have an environment here that we foster that allows us to come together.’ And boy, you do that at the end of a meeting and no matter how difficult the conversation was everybody walks away with this incredibly warm feeling about each other, about themselves, and about the whole team. It is magical.”

There is something else that Haudan believes in—humor. At Root, there is a practice called Rooties and Tooties. Rooties are awarded for good work, like the Oscars. A Tootie is a spoof of a fellow employee. For example, Haudan has been lampooned by staffers for being too long-winded in his presentations or for not really doing any work; they joke that he has his executive assistant do everything. By encouraging such comedy, the company breaks down barriers, and people treat one another as people. Informality is important.

Fun is important, and whatever method you choose, it is a means of making a connection from one person to another. Such a connection facilitates commitment to the work, but also to colleagues and even bosses. This is fundamental to stimulating and growing engagement.

Engagement can mean many things to many people but, bottom line, it can be summed up by the desire to create a workplace atmosphere where people feel appreciated and are motivated to do good work.

Closing Thought: Engagement

A leader is more than a sum of what he has accomplished. A leader is judged by how well he enabled others to achieve their aims in ways that benefit the entire organization. That is the essence of engagement—bringing people together for common purpose.

When people are united in purpose they can accomplish things together that they might not have thought possible. And that’s the secret of positive engagement. People apply their own skills, individually and collectively, in order to achieve desired and sustainable results.

Engagement = People + Commitment

Leadership Questions

- What are you doing to connect more effectively with others?

- What do you think you could be doing better?

- What changes will you make so that you make personal connections a key priority?

Leadership Directives

- Engagement is the process of connecting one person to another. Learn to work with and for others as a means of achieving mutually beneficial goals.

- The first form of engagement is communication. Use your words to initiate a connection but follow through on that connection with positive actions.

- Our behavior sets the tone for how others will regard us. Adopt a perspective of seeking to assist rather than to confront or disrupt. This approach promotes greater openness.

- We reinforce engagement through our actions: consider how well you reach out to others, listen to what they have to say, and pay attention to their ideas.

- Lead with a sense of inclusiveness. That is, keep people informed with news, apprised of the situation, and engaged in the work.