Retirement Distribution Planning

Introduction

Throughout people’s working careers, they make periodic contributions into their retirement accounts. At some point, they will retire and need to withdraw money. Retirees need to understand the potential tax implications of this process. They also need to understand a few special rules that could save taxes over the long term.

The American government permits tax-deductible contributions under certain plan types. This is done to encourage the participants to save so that they are not solely reliant upon Social Security for their retirement well-being. However, the government does want to eventually generate taxable income for retirees so that they limit the length of the tax deferral period. They accomplish this by establishing an age when the retiree must begin to withdraw money and the government even provides the retirees a formula for the amount of their required minimum distribution (RMD). A well-established distribution plan is as important as a well-structured saving plan.

Learning Goals

•Explain the general tax treatment of retirement distributions

•Understand the §72(t) early withdrawal rules

•Identify the various methods of recovering cost basis

•Understand what counts as a qualified Roth IRA distribution

•Determine if a certain retirement account balance is eligible and advisable to be rolled over into another tax-deferred plan

•Describe the rollover options for the beneficiary of a retirement asset

•Understand the potential application of the net unrealized appreciation (NUA) rule to an employer-sponsored retirement plan

•Understand the RMD rules

•Describe how the RMD rules apply to a deceased participant

General Tax Treatment of Distributions

If a taxpayer does not properly understand and adjust for the tax implications of taking distributions from their retirement savings accounts, then they may pay taxes that they otherwise did not need to pay.

The general rule is that all distributions from retirement savings accounts will be taxed as ordinary income (normal tax rate schedule) unless some special rule applies. One notable special rule that should not be violated, if at all possible, relates to early distributions. Any distribution from a retirement savings account before the taxpayer turns 59½ will incur a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty above and beyond the applicable ordinary income tax rates.

Ordinary income taxes and early distribution limitations both apply to deductible contributions. There is a special rule for nondeductible contributions that will be explained thoroughly in the Recovery of Cost Basis section in this chapter.

The early distribution penalty is also known as a 72(t) penalty. This is merely the IRS section that creates the 10 percent penalty. However, the 10 percent penalty amplifies into a 25 percent penalty for savings incentive match plans for employees (SIMPLEs) if the early distribution occurs within the first two years of the employee’s participation. It should also be understood that most hardship withdrawals are subject to the 72(t) penalty. The only hardship withdrawals that do not involve a 10 percent penalty are withdrawals related to disability, certain medical expenses, and a qualified domestic relations order.

There are some notable exceptions to the 72(t) early withdrawal penalty. The first exception is for a beneficiary who is required to take distributions from an inherited IRA. This beneficiary may be younger than 59½, but he or she can escape the 10 percent penalty because it was inherited. The second exception is in the event of disability. This exception dovetails with the disability-inspired hardship withdrawal previously mentioned. The third exemption is commonly called a 72(t) distribution by financial practitioners. This exemption is also called a series of substantially equal payments (SOSEP). Basically, taxpayers who need to take an early withdrawal could begin to take distributions without the 10 percent penalty if they establish a series of payments based upon a special formula. There are online calculators available to help a client establish the payment amount.

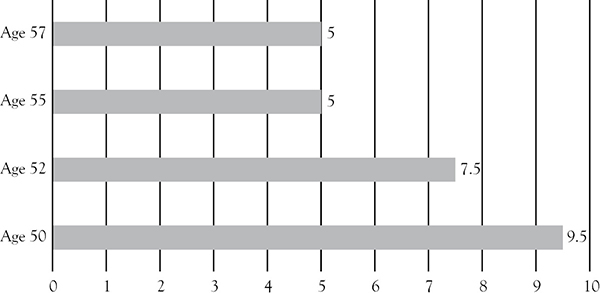

A 72(t) distribution must last for the longer of five years or until the taxpayer reaches age 59½. Figure 23.1 illustrates that someone who is 57 when he or she begins a 72(t) distribution will need to withdraw funds for five years (until age 62), while someone who begins a 72(t) distribution when they are 50 will need to take distributions for 9½ years (until they reach age 59½). With a 72(t) distribution, the distributions cannot deviate by even a penny from the calculated distribution amount for the entire period of required distributions. Any alteration in the distribution amount will result in all distributions (retroactively) being deemed early distributions and therefore assessed with a 10 percent retroactive penalty. Not the desired result!

Figure 23.1 Length of SOSEP depends upon starting age

Abbreviation: SOSEP, Series of substantially equal payments.

The 72(t) Special Exception

There is a special exception for qualified plan participants or those with a 403(b). For this special exception to apply, the assets must remain in the qualified plan or 403(b). This means that the assets cannot be rolled over immediately into a traditional IRA. The exception applies only to those who have separated from service (terminated employment) after age 55. If the taxpayer meets these two basic requirements (age and the assets remain in the original plan), then distributions can be made from the account without the 72(t) penalty.

Consider a client who is 56 years old and has just been a victim of downsizing (he just lost his job). He is instantly plunged into an unplanned financial reality as well as an emotional roller coaster. This taxpayer’s financial advisor recommends that he rollover his 400,000-dolar 401(k) into a traditional IRA to provide for greater investment flexibility (more investment choices). If the taxpayer follows this advice, then he will not be able to take penalty-free distributions. If he does proceed with the rollover, then his best option is to establish a 72(t) distribution to escape the penalties. One practical idea is to split the $400,000 into two separate traditional IRAs. The first IRA would have only enough money in it to fund a 72(t) distribution that exactly meets the taxpayer’s needs. The other money could remain in a second IRA and continue to compound, free from the constraints of a 72(t) distribution schedule. There is no requirement that all traditional IRAs registered in a taxpayer’s name be used to calculate a 72(t) distribution. This calculation is based on an account-by-account basis.

There are also a few notable 72(t) penalty exceptions that apply only to IRAs. A penalty-free withdrawal can be made from an IRA to pay for qualified postsecondary (college) education expenses. There is also a unique caveat that permits penalty-free withdrawals up to $10,000 for the purchase of the IRA owner’s first house. A third penalty-free category available only to IRA owners is for health insurance premiums for those receiving unemployment benefits.

Consider a client who is 45 years old and wants to take a $25,000 hardship withdrawal from her 401(k) to pay for a child’s college education. What is the 72(t) application for this scenario? Recall that the only hardship withdrawals that do not involve a 10 percent penalty are withdrawals related to disability, certain medical expenses, and a qualified domestic relations order. Qualified postsecondary education expenses to not qualify for penalty-free treatment. A 10 percent 72(t) penalty will be assessed on this hardship withdrawal. If this client wanted to make the distribution from an IRA, then the penalty would be waived.

Recovery of Cost Basis

In Publication 551, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) defines cost basis as the original cost paid for an item.1 The concept is that the original cost was paid for with money that has already been taxed once, and it would be counterproductive to tax it a second time. Cost basis therefore becomes an amount of money that is in a taxable situation but not taxed.

What might create a cost basis to accrue in a retirement account? There are two likely candidates. The first one is nondeductible contributions. Recall that nondeductible contributions are made from after-tax money. If they did not accrue as cost basis in taxable account, then double taxation would occur. The second candidate is the cost of pure insurance that was included on employees’ W-2 if they purchased a life insurance product within their employer-sponsored retirement account.

There are four different distribution scenarios when cost basis will become very valuable. The first scenario is with a lump-sum distribution that is not rolled over into an IRA. In this instance, the entire cost basis is recovered immediately. Consider a client with a 401(k) with a $150,000 balance and $25,000 of nondeductible contributions. This client would have $125,000 ($150,000 − $25,000) of taxable income in the year of the distribution.

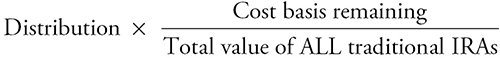

The next two scenarios both involve a rollover. In one rollover option, a client can roll over all deductible contributions as a first step. The second step is to take a tax-free distribution of all nondeductible contributions to recapture the cost basis all at once. Consider the client with $150,000 in a 401(k) and $25,000 of cost basis. She could elect to roll $125,000 into a traditional IRA and then receive a $25,000 tax-free distribution. The second rollover option is to roll all assets, both deductible and nondeductible contributions, into a traditional IRA. Again, consider our client with a $150,000 balance in the 401(k) and a $25,000 cost basis. If the client rolls the entire $150,000 into a traditional IRA, then she will need to calculate a prorated cost basis recovery every time a distribution is taken. Let us further assume that this client already has a second IRA with a $100,000 balance. The client keeps both IRAs separate and decides to take a $10,000 distribution from the recently rolled-over IRA. The pro rata cost basis recovery is determined using Formula 23.1.

(23.1)

(23.1)

Applying Formula 23.1, we find that the actual dollar amount of pro-rata cost basis recovery will be $1,000 [$10,000 × ($25,000/$250,000)]. This means that the $10,000 distribution will result in $9,000 of taxable income and $1,000 of tax-free cost basis recovery. The remaining cost basis in the IRA is now $24,000 ($25,000 − $1,000). This number will become the numerator for the pro-rata cost basis recovery calculation the next time a distribution is needed. The important note to this process is that the denominator in this equation ($250,000) must include all traditional IRAs owned by this taxpayer.

The last possible cost basis recovery option is reserved for those who annuitized (turned their retirement plan into an annuity with a series of payments). These clients will also use a pro rata cost basis recovery calculation, but this one is different from the discussion in the preceding text. Consider a client who has a 403(b) and decides to annuitize his balance when he retires next month (on the 65th birthday). By annuitizing, this client will no longer have an account where he can take ad hoc distributions if a need arises. However, he will have a guaranteed (by the financial health of the insurance issuing company) series of payments during retirement. Assume that the payments are designed to last for 25 years (300 months) and that the client has a cost basis in the 403(b) of $40,000. The cost basis recovery is $133.33 ($40,000/300) per monthly payment. If this client’s monthly annuity payment were $1,133.33, then he would enjoy $133.33 tax-free and the other $1,000 would be received as fully taxable income. Once the client recovers all of the cost basis (perhaps cost basis is specifically designed to be recovered faster than the annuity term), then all distributions become fully taxable.

Qualifying Roth IRA Distributions

A qualifying Roth IRA distribution will be available after one of three trigger events occurs. The first trigger event is the attainment of age 59½. The second trigger is the occurrence of either death or disability before age 59½. The third and final trigger event is an exception for a $10,000 distribution for a first-time homebuyer.

Once a trigger event has occurred, qualifying distributions are tax-free from a Roth IRA only if the distribution does not violate a special five-year rule. Roth IRAs make a big deal about the fifth anniversary of when the first contribution was made into the taxpayer’s first Roth IRA. All Roth IRAs are aggregated together for purposes of calculating the five-year anniversary. An important caveat is that Roth 401(k) plans are not aggregated with Roth IRAs for this purpose. The path of least resistance, should the five-year anniversary become an issue, is to wait until the Roth 401(k) is rolled over into a Roth IRA before beginning distributions. The clock for the five-year time frame begins on January 1st of the year in which the first contribution is made to a Roth IRA. The whole purpose for this rule is to avoid taxpayers contributing to a plan in retirement, enjoying tax-free compounding for only a few years, and then receiving tax-free distributions. Roth IRAs are intended to be longer term retirement savings instruments.

Consider a client who contributes first to a Roth IRA on April 14, 2012. The five-year anniversary is measured by tax year, and therefore, this taxpayer’s five-year anniversary will occur on December 31, 2017. After this anniversary date, the Roth IRA owner can take qualifying (tax-free) distributions, assuming a trigger event has also occurred.

A nonqualifying Roth IRA distribution will occur if taxpayers are either younger than 59½ years OR if they need to violate the five-year rule for whatever reason. The application of this rule is straightforward. Taxpayers can withdraw their after-tax, nondeductible Roth IRA contributions at any time, but they cannot distribute any earnings on those contributions without paying a 10 percent 72(t) penalty for early distributions. Roth 401(k) plans have another unique rule. With a Roth 401(k), nondeductible contributions must be prorated in the same manner as a traditional IRA. The solution to this rule is to roll over the Roth 401(k) into a Roth IRA assuming that the taxpayers are eligible for a rollover. They are only eligible to roll over an employer-sponsored plan if they have severed employment with that sponsoring employer.

Consider a client who is 55 years old. She began contributing to a Roth IRA four years ago and has already turned the $21,000 of contributions into a very nice $40,000 current account balance. In one scenario, this client needs to immediately withdraw $15,000 to purchase a piece of land. She has access to the $15,000 without 72(t) penalties because this amount is less than the total contributions. In another scenario, the taxpayer needs to withdraw the entire $40,000 for the land purchase. In this case, the taxpayer will have $21,000 of tax-free distribution and $19,000 that is both taxed and assessed at 10 percent 72(t) penalty.

Rollovers

Rollover is a technical term used to describe the movement of money from one plan type into another plan. This sounds like an amendment, but the difference is that a rollover is a case-by-case process and is not done for all participants in the plan. The most common rollovers are from either a 401(k) or a 403(b) into a traditional IRA. To rollover the balance in an employer-sponsored plan, the participant must first sever service with the employer. A 401(k) cannot be rolled into a traditional IRA while the employee still works for the sponsoring employer.

Recall that direct rollovers are between two retirement plan custodians. For example, a participant might transfer his or her 401(k) at Vanguard into a traditional IRA at TD Ameritrade. In the instance of a direct rollover, the money has 60 days to leave the first custodian and arrive in the participant’s traditional IRA at the new custodian. If the 60-day window is violated, then an early distribution may be declared. This time frame was established to prevent any funny business in the transfer process. This time window is typically not a problem because most transfers now take place electronically. However, if the 60-day window is breached for no fault of the participant, then the participant can request a waiver from the IRS.

The big problem is when a taxpayer chooses, knowingly or unknowingly, to elect an indirect rollover. In this case, a check comes to the participant from the first retirement custodian (i.e., 401(k) vendor), and then it is the taxpayer’s responsibility to deposit the money into the new traditional IRA. In this instance, the IRS mandates that the first custodian must withhold 20 percent for taxes and send that money to the Department of the Treasury. The problem is that the taxpayer must come up with the money that was paid to the IRS from an outside source to deposit the money into the new traditional IRA to avoid being deemed as an early withdrawal.

Consider a client who has $100,000 in a 401(k) at Vanguard and unknowingly elects an indirect rollover. Vanguard will send this taxpayer a check for $80,000 and they will simultaneously send a check to the Department of the Treasury (bill collector for the IRS) for $20,000. The taxpayer will get this money back when he files his tax return, but he will wait for that to occur. In the meantime, he must deposit the full $100,000 into a traditional IRA to avoid any unplanned actual taxation or 72(t) penalties if the rollover occurs before age 59½. The taxpayer will need to lend himself $20,000 from another source to make the full indirect rollover happen, and then he will be reimbursed when tax time comes around…in theory.

There are a few situations where a rollover is not permitted. The first situation is when the client has begun to take government-mandated withdrawals, which you will learn about later in this chapter. The mandated withdrawals cannot be rolled over because that would violate the intention of requiring a withdrawal to begin with. The second situation involves 401(k) hardship withdrawals. These hardship withdrawals cannot be rolled over. The third situation is when a SOSEP has been established for an account. It does not matter is the SOSEP is established as a life annuity or as a 72(t) distribution. Either way, the presence of a SOSEP will remove the option of rollover.

It is very useful to ask: What is the purpose? The purpose of a rollover is to permit an extended period of tax-favored compounding. By selecting a rollover option, the taxpayer will effectively extend the tax-favored compounding from the point of retirement (or simply severance of employment) as long as possible.

Beneficiary Rollovers

In the previous section, you learned about rollovers as they are applied to retirement account owners. Those who inherit an IRA are also able to apply the rollover principle in a different form. These are called beneficiary rollovers. Spouses who inherit an IRA are in a unique situation. They have two options. The first option is to roll their deceased spouse’s IRA into an IRA in their own name. The asset is then treated as if it always was owned by the surviving spouse. The second option is to leave the IRA in the now deceased person’s name. In this sense, the spouse steps into the decedent’s shoes. The primary reason for choosing option 2 would be if the surviving spouse is younger than 59½ while the decedent was older than 59½. In this case, the younger surviving spouse could access death benefit distributions without the 10 percent 72(t) penalty.

Nonspousal beneficiaries are a whole other scenario. They must roll the decedent’s IRA into a beneficiary IRA in the name of whoever inherited the asset. The new owner of a beneficiary IRA will need to take withdrawals from the account effective immediately. There is no longer an age 59½ limitation. The IRS has waited long enough to be able to tax that money. The owner of the beneficiary IRA will need to establish what the government’s required distribution is for them and proceed to follow the mandated schedule.

There is another very important issue for beneficiary IRAs. Under normal circumstances, assets held within an IRA are usually exempt from bankruptcy proceedings. The United States Supreme Court has recently ruled that this protection does not extend to beneficiary IRAs unless the beneficiary is a spousal beneficiary2. This means that a nonspousal beneficiary who inherits an IRA and subsequently files for bankruptcy could see the inherited IRA consumed by bankruptcy creditors.

NUA Rule

There is a very special rule known as the NUA rule that applies to employer-sponsored retirement accounts when the participant owns employer stock within their plan. The application of this rule involves the participant receiving a lump-sum distribution of ONLY the employer stock and the remainder being rolled over into a traditional IRA. These shares will now be held in a nonqualified account registered in the participant’s name without the limitations of an IRA. If this rule is applied, then upon distribution of the lump sum of employer stock, the cost basis (original cost) of the employer stock is taxed as ordinary income. A 10 percent 72(t) penalty will apply if the taxpayer is younger than 59½ when they apply this rule! The value of the employer stock between the cost basis and the price of the stock at the time it is distributed is taxed at long-term capital gains rates when the asset is ultimately sold. Any additional appreciation or depreciation in the stock will also receive capital gains treatment. These capital gains may be long term or short term depending on how long the taxpayer holds the shares after distributing them from their retirement account.

This is an amazing opportunity for participants with a reasonable amount of employer stock in their employer-sponsored retirement plan. As you no doubt could guess, there are caveats. The first caveat is that the NUA rule cannot be applied to either a simplified employee pension (SEP) or a SIMPLE. The idea is that SEPs and SIMPLEs are used by small businesses, and the IRS does not want the small business owner to escape taxation on the small business that they built by applying the NUA rule. This rule is intended for publically traded companies. The second caveat is that application of the NUA rule will negate the ability for the participant’s estate to use stepped-up basis on these shares.

Stepped-up basis is a tremendous benefit for an inherited nonqualified account. Assume that a taxpayer has $200,000 in a nonqualified account, and the cost basis in the account is $50,000. If this taxpayer chose to liquidate the taxable account herself, then she would pay capital gains taxes on $150,000 ($200,000 − $50,000). However, if this same individual holds the assets until death and the account is inherited by someone else, then the inherited account will have a new basis of $200,000 and not $50,000. This is known as stepped-up basis, and it is a tremendous value! If the $200,000 is a joint account between a husband and wife, and one of them passes away, then the surviving spouse receives partial stepped-up basis. He or she will receive 50 percent of the original cost basis and 50 percent of the date-of-death value as the new basis. In this example, the new partial stepped-up basis will be $125,000 [(50% × $200,000) + (50% × $50,000)].

Required Minimum Distribution

Required minimum distribution, which is the government’s mandated distribution amount, is commonly called simply RMD by practitioners. You are already aware that distributions can be taken without the 72(t) penalty after a client reaches age 59½. At some point, the federal government wants taxpayers to begin taking distributions and therefore receiving taxable income. The government splits their required distributions into three categories. The categories are for traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs, and qualified plans.

Within a traditional IRA, taxpayers are required to begin taking withdrawals from their account after they turn 70½. What is with the half birthdays! In 1962, when the first retirement account (Keogh) was being born, the age of 60 was selected by Congress because it corresponded with the normal retirement age at that time. Someone brought up that the insurance industry’s actuaries use 59½ as an insurance age-equivalent number of years in place of 60. Therefore 59½ was rubber-stamped by Congress as the official age, and it has not been changed since. The magic number of 70½ probably stems from two sources. National retirement plans all the way back to the first plan offered by Germany in 1889 have used 70 as a benchmark retirement age. Congress probably used 70½ not because of insurance equivalency, but to keep it logically consistent with the 59½ already on the books.

The government has a series of tables that are used to calculate a client’s RMD amount. In practice, a financial professional will use an RMD calculator to find the value. The dollar amount provided by an RMD calculator must be withdrawn by December 31 of each year, or the government will impose a 50 percent penalty on the amount that was not withdrawn. The RMD calculation is based upon the previous year’s ending balance and the age of the taxpayer and possibly the age of the beneficiary if he or she is more than 10 years younger than the taxpayer.

There is a special rule for the taxpayer’s first year of RMD—the year in which they turn 70½. In this first year, they can delay taking RMD until the next April 1. This is known as the required beginning date (RBD). If a taxpayer waits until the April 1st following their 70½ “birthday,” then they may be taking two year’s distributions as taxable income in the same year. Consider a client who turns 70½ in October of 2014 and has 2014 RMD of $5,642.13. This taxpayer could wait to receive the 2014 RMD until April 1, 2015. The $5,642.13 distribution is then taxable income for tax year 2015 even though it was a 2014 RMD distribution. Distributions are taxed in the year in which they are physically distributed. This client will also need to take a 2015 RMD distribution in tax year 2015. This means that by delaying their RMD, this client has created a double taxable distribution in their first year.

As was previously mentioned, Roth IRAs do not have an RMD amount associated with them. The government does not mandate any specific withdrawal from a Roth IRA until the Roth IRA is inherited by the Roth IRA owner’s heirs. At the point of inheritance, the RMD requirement will be applied in the same manner as a traditional IRA (using the previous year’s ending balance and an RMD calculator). The benefit of not mandating RMD is that Roth IRA balances can continue to compound tax-free for longer periods of time. This potentially creates a larger estate than would otherwise have existed.

There is a special rule that applies to qualified plans. The RBD can be postponed until the April 1 following retirement IF the participant remains working past age 70½ and also assuming that the assets remain in the qualified plan until distributions begin. This special rule is only available to those who are not 5 percent owners in the employer.

Distribution Issues for a Deceased Participant

There are unique distribution rules that apply when a participant dies. This discussion assumes that the participant dies after the RBD. For the tax year in which the participant dies, the RMD is calculated as if he or she were still living. The RMD must be distributed to the deceased participant’s estate before the account can be transferred to any beneficiaries. After the RMD has been satisfied, the disposition of the account will depend on who the beneficiary is.

Spousal beneficiaries typically roll the decedent’s IRA into their own IRA of the same type (traditional into traditional and Roth into Roth). However, a spousal beneficiary could leave the account in the decedent’s name. They might do this if the decedent was older than 59½, thus enabling 72(t) penalty-free distributions, and the surviving spouse is younger than 59½. Other than for this reason, there is no need to leave the account in the decedent’s name.

Nonspousal beneficiaries, like a child, grandchild, or other relative, will establish a new beneficiary IRA (or beneficiary Roth IRA). In either case, the nonspousal beneficiary is required to receive RMD distributions factored based on the new owner’s life expectancy. Note that a nonspousal beneficiaries cannot roll a deceased participant’s account into their own traditional IRA; they must open a separate beneficiary traditional (or Roth) IRA.

It is also possible to have a nonperson beneficiary, like a trust or a charity. The RMD for a nonperson beneficiary is factored based on the decedent’s life expectancy (ignoring that they already expired) from government tables.

What happens if the participant dies before the RBD? Spousal beneficiaries will typically roll the deceased participant’s account into their own IRA and then follow RMD rules as they would if it were simply their own asset. A nonspousal beneficiary will roll the account over into a beneficiary IRA and then take RMD based upon the beneficiary’s life expectancy from a government table. The big difference is for a nonperson beneficiary. A nonperson beneficiary will need to withdraw the entire account balance (and therefore incur taxable income) over a five-year window. This becomes an issue if there are multiple beneficiaries and one is a nonperson entity. This issue is discussed in the next section.

Other Distribution Issues

If multiple beneficiaries exist for the same deceased participant’s account, then the rules state that the oldest beneficiary (or the one with smallest distribution period) will establish the distribution period for all beneficiaries. This can be a problem if a participant establishes a spouse and a charity (or a trust) both as beneficiaries on the same retirement account. The spouse will then be forced to distribute all assets within five years and pay a great deal in taxes that might otherwise have been avoided.

There is no way to alter the beneficiaries on an account after a participant has died, but the IRS does provide a loophole. For the purposes of calculating RMD amounts, the IRS will calculate RMD based upon all beneficiaries who have not been paid out as of September 30 following the participant’s death. As long as the nonperson’s portion of the retirement account has been transferred to the new owner by the September 30 deadline, the other beneficiaries can follow their own distribution rules based upon their status as spousal or nonspousal beneficiaries. This also works for nonspousal beneficiaries. Basically, all beneficiaries should have their own account established by the September 30 deadline to avoid force RMD amounts that are more accelerated than need be.

Sometimes, taxpayers will use a trust as a portion of their estate plan. This instrument enables the taxpayers to control posthumously how their assets are distributed and even apply special thresholds for beneficiaries to meet (like levels of educational attainment or age thresholds) before money is distributed by the trustee. The trust will become irrevocable (unable to be altered) after the taxpayer has died. If a trust inherits retirement account assets, then the various beneficiaries’ ages are used to determine the RMD amounts.

Certain participants chose to annuitize their retirement accounts. In this case, RMD is calculated in a different manner. RMD compliance is tested when the annuity payments begin. Insurance companies are aware of this special rule, and they factor this requirement into calculating the annuity amount to begin with. The annuity payments must start before the RBD.

Another important nuance of RMD calculation is that all IRAs are aggregated for determining RMD compliance. Consider a taxpayer who has three separate traditional IRAs each with $200,000 in them. He also has an RMD amount of $21,794.17 based upon his age and the oldest beneficiary. He can aggregate the IRAs in terms of taking the required $21,794.17 out of only one IRA and leaving the other two untouched. It is also possible to aggregate 403(b) accounts. It is not possible to aggregate qualified plans. This is one reason why qualified plans are often rolled into a traditional IRA after retirement occurs.

Discussion Questions

1.A 72(t) penalty amounts to a 10 percent penalty for all plan types.

2.Are all hardship withdrawals exempt from a 72(t) penalty?

3.What are the three generic exemptions to a 72(t) penalty?

4.What is the tenure requirement for a 72(t) distribution (SOSEP), should that be applied to an account?

5.What special 72(t) exemption is available to qualified plan participants?

6.What special 72(t) exemptions are available only for traditional and Roth IRA owners?

7.An IRA owner has nondeductible contributions of $25,000 in his traditional IRA, which is valued at $300,000. He plans to take a distribution of $20,000 and understands that the nondeductible contributions have created a tax-free cost basis. He thinks that the full $20,000 will be tax-free. Is he correct?

8.Reconsider the IRA owner who has nondeductible contributions of $25,000 in his traditional IRA, which is valued at $300,000. He still plans to take a distribution of $20,000. What is his cost basis recovery?

9.A client needs to withdraw money from her Roth IRA. She is 49 years old and has contributed $57,000 into a Roth IRA, which is now worth $242,000. What are her options if she needs to withdraw $32,000 to purchase a new car? What if she needed to withdraw $65,000 to pay for an executive MBA degree?

10.With respect to the five-year rule, are all Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k)s aggregated in meeting the test of tenure?

11.Why might a spousal beneficiary keep an IRA in the now deceased spouse’s name?

12.Are applications of the NUA rule free from 72(t) penalties?

13.Name two significant limitations imposed by the NUA rule.

14.A client of yours applies the NUA rule. He had a cost basis of $57,000 and the employer stock was worth $233,000 when they applied the rule and removed the stock from the umbrella of a tax-advantaged plan. The client waits two years until the stock’s value is $311,000 before selling. Describe the tax implications and when the taxes will be paid.

15.This same client applies the NUA rule with a cost basis of $57,000 and the employer stock was worth $233,000 when they applied the rule and removed the stock from the umbrella of a tax-advantaged plan. However, when the client sells the stock two years later, its value has declined to $174,000. Describe the tax implications and when the taxes will be paid in this circumstance.

16.Is it true that a client must begin taking RMDs by the time they reach age 59½?

17.A client reached the RBD on April 24, 2013. He elected to apply the April 1 rule. What does the tax situation look like in 2013 and in 2014?

18.A client dies at age 75 and leaves an IRA to heirs. With respect to RMD, what must happen before the IRA is distributed?

19.A client dies before the RBD. With respect to RMD, what happens if the spouse inherits the IRA?

20.A client dies before the RBD. With respect to RMD, what happens if the children inherit the IRA?