Crafting the Corporate Strategy

The investor relations officer (IRO) has an important role in helping craft the corporate strategy and the corporate story, and then conveying strategy and story to investors and financial media.

Corporate strategy now represents the difference between success and failure. Prior to the competitive pressures of the 1970s, many organizations did not possess “strategies,” simply collections of different businesses and products. Many British businesses were hopelessly diversified; others were overfocused on single market niches.

The traumas of the 1970s saw the return to a more conservative style of management as the confident belief that markets would be ever-expanding evaporated. Conglomerates were encouraged by consultants and investors to slim down and focus on a narrower range of activities. A new generation of business leaders emerged who were focused on shareholder returns, corporate strategy, and organizational transformation. The weakening of trade union power allowed models of rapid organizational change to reemerge, although this was too late to save some British businesses. At the same time, a report by Lee and Tweedie (1977) suggested that accounting information was incomprehensible to many investors and should be supplemented by narrative content.

In the United Kingdom, financial analysts quickly adopted the new methods of strategic analysis such as Porter’s Five Forces (Porter, 1980). The growth of the consultancy industry and the rise of the MBA circulated the new views on corporate strategy. Peters and Waterman in 1982 published a new type of strategy book that blended academic research with corporate case studies and offered bite-size nuggets of corporate advice along with universal principles of good strategy. The book developed a cult following and sold three million copies within four years.

Henry Mintzberg (1987) wrote about the difference between strategy as plan and strategy as pattern. Strategy is not just what the organization intends to do (the strategic plan) but also the pattern of existing activity. If observers see a difference between strategy as preached and strategy as practiced, then the organization’s strategic credibility will suffer. Another danger is that short-term strategies to take advantage of current opportunities (what Mintzberg calls “ploys”) may compromise the long-run strategic direction of the organization. The listed company is in the fortunate position of being carefully monitored by analysts, investors, and journalists who are looking for inconsistencies in what the organization says and what it does, or between what the organization does in one place and what it does in another place. The firm has to monitor itself as carefully as outside observers monitor it, and the IRO is in a key position to guard the consistency of the corporate strategy and the corporate story.

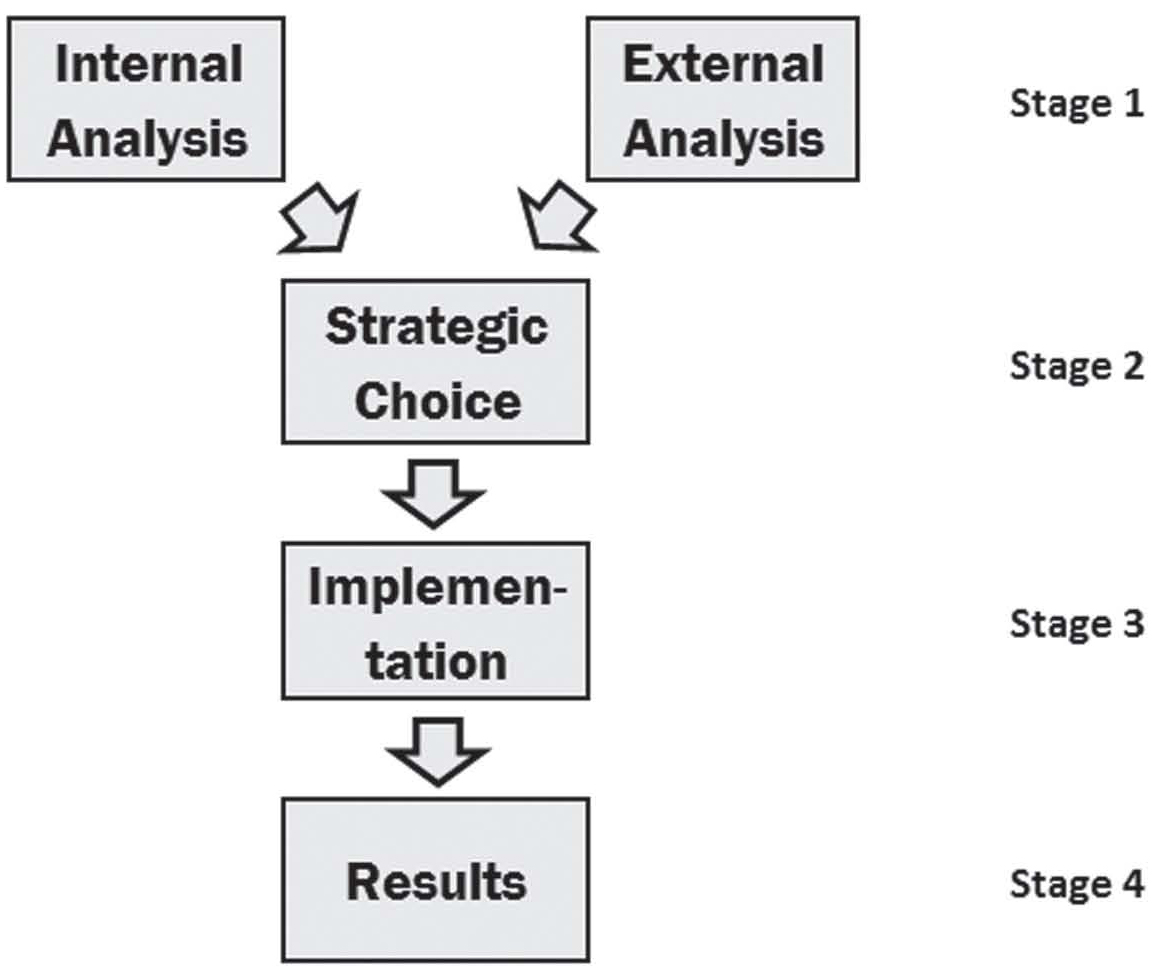

As Figure 7.1 demonstrates, strategic choice is based on two prior assessments: the assessment of internal capabilities and the assessment of the environment of the firm, both the industry environment and the wider macroeconomic environment that all firms face. Results however, which is what investors are ultimately seeking, also depend on successful implementation. Therefore, disappointing results raise the question of whether the strategy was at fault or whether the problem is one of implementation. In order for results forecasts to be credible, corporations must convince analysts and investors that they have competence in implementation in addition to their strategic choice being based on solid analysis.

Corporations will find that certain analysts and investors can give great insight into their industry environments because of their access to macroeconomic analysis from professional economists (which firms rarely have direct access to) and because of their access to the management teams of competing firms. One of the greatest benefits of good relations with analysts and investors is the opening up of two-way communication which can yield helpful industry and macro-level intelligence for the management team.

Figure 7.1 The strategy process

This author has read dozens of strategy textbooks, but has never found one that referred to the strategic preferences of investors, or one that outlined a workable process of consulting with investors. Many companies seem to leave consultation with investors till a very late stage of strategy formulation, either for fear of “selective disclosure” or because investors are not regarded as having a useful contribution to the process. We suggest that it is highly advisable to both consider the general perspective of investors and to consult with key investors before publication. The general strategic preferences of fund managers are discussed by Golding (2003: 166) and include the following:

• Good numbers

• Growth potential—in a growing market

• Simple ownership structure

• “Pure play”—a simple business

• Simple corporate story—e.g., “growth” or “recovery”

• Simple and convincing strategy

• Merger and acquisition potential

• Size—larger firms preferred, ideally dominating the profitable segments of their market

• Quality products—differentiation strategy rather than competing on price

• Management team with a record of delivery

Crafting the Corporate Story

Storytelling is a natural and powerful method of communication. The human mind connects events chronologically and causally, and stories provide these connections in ready-made form. A story can be defined as a narrative of events in a generally chronological form, with certain events, people, and moments emphasized to provide meaning. Stories provide reassurance to people since stories are easily comprehensible and memorable and most people believe themselves to be very capable of testing narrative fidelity, that is, whether the story “rings true” or not (Rentz, 1992). Narrative is central to western culture. For instance, children are taught using stories from an early age, and the untangling of events into a clear chronology is also an essential part of the trial of a case in the law courts, and so the practice of using narrative both to understand and to communicate is very familiar.

Storytelling is an essential part of many professions, with journalists, lawyers, police officers, historians, and biographers all needing the skill of finding and piecing together facts to create a meaningful narrative. Differences in access to information, selection, juxtaposition, and emphasis will change the meaning of the story. Despite their quantitative bias, investors and analysts share this cultural love of stories. Additionally, analysts, while needing to demonstrate objectivity and mastery of detail, also need “an angle” for their commentary. The analyst is part number cruncher, but also part journalist. Each piece they write has to have a purpose and a point, and this is why the “story” element is so important for analysts. While skilled users of the financial statements and company announcements can craft a substantial part of the corporate story given enough time, many analysts and investors do not have the time or resource to work from the ground up at forming their own narrative. While some analysts and investors are highly autonomous and will build their own understanding of the company from scratch, many others want help and shortcuts to understanding. If the company presents a credible and evidenced story to analysts and investors, then that story can become the received wisdom of the financial community.

Figure 7.2 The interdependence of strategy and story

Simple stories are best. Golding (2003:169) suggests that there are a very limited number of effective investment stories, the main ones being “growth”, “new management/recovery,” and “industry consolidation”.

As Figure 7.2 shows, the corporate story is not merely a passive narrative based on corporate strategy. The process of shaping a credible corporate story will involve making improvements to the corporate strategy. The result of this process is a combined corporate strategy story that generates both internal and external support and sustainable corporate profit.

The first test of the combined corporate strategy story is whether it can hold up under internal criticism, the second test is whether it can hold up under the criticism of trusted stakeholders, the third test is whether it can hold up under public scrutiny, and the fourth and ultimate test is whether it can hold up over time and the pressure of a changing environment.

The corporate story is not simply a tale of what might happen. The management team need a corporate story that can connect past, present, and future. While CEOs love to talk about their plans for the future, analysts will want to ground forward projections on an understanding of the current business and the management’s team’s past record at delivering results.

Since the early 1980s investor and analysts have expected managements to talk the languages of strategy and implementation as well as the language of financial results. These three subjects can be blended together as shown in Figure 7.3 to craft the corporate story. The story includes past, present, and future actions since corporate strategy emerges from an understanding of the corporation’s past and present. The corporate story is a sense-making narrative which turns isolated facts into a coherent and attractive pattern of activity.

Figure 7.3 Crafting the investment story

Figure 7.3 shows how the strategic process can be converted into a story. Past strategy, present strategy, and future strategy are weaved into a story, using stages 2, 3, and 4 of Figure 7.1 for each time period. Of the three elements of the story, “implementation” is the one most difficult to ascertain from corporate documents, and this is where analysts can add most value, through their face-to-face meetings with management. Assessments of implementation ability are subjective, but tend to involve judgments of management team track records, the ability of management to answer questions on current projects, the availability of good management information to support corporate decision-making, and the quality of the layer of managers immediately below the executive board. This team of managers are responsible for implementing management plans and will also represent the succession plan, being the executive board of the future. In this subjective assessment, analysts will tend to have personal methods of research and “rules of thumb,” and it is worth speaking to analysts to discover what their assessments of management quality are based on.

The other characteristic of the story is that it should be current. A corporate story is not like a classic novel that satisfies readers for generations; it needs to be updated when the environment changes, or when goals are reached.

Analysts and journalists supply investors with ideas, facts, and opinions, which forms the raw material of much of investor decision-making. A company that refuses to communicate with analysts and journalists is giving them the power to shape the company’s profile. To quote Hobor (1997) “not communicating takes the message out of the control of the company and puts it in the hands of others.”