The Ethics of Investor Relations

Investor relations (IR) is never ethically neutral. IR acts as a channel between two essential, productive and beneficial activities, and assists both of them: (1) the corporate task of creating customers, employment, and economic wealth and (2) the equity market task of helping the best companies grow and enabling a wide audience to benefit from corporate success.

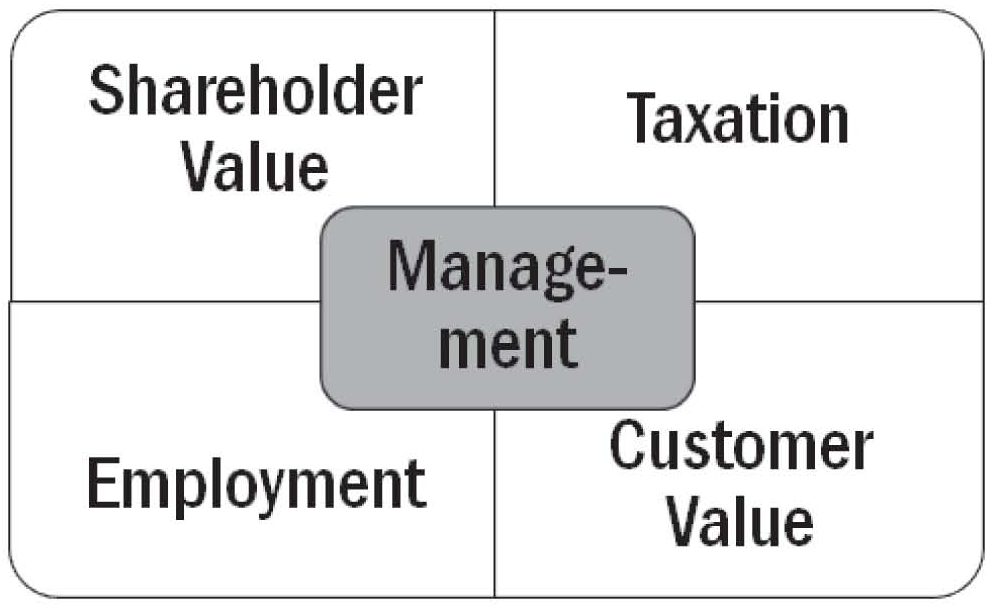

The corporation is not simply a device for making profit for owners. Since the 16th century, corporations have played an essential part in the economic growth of European states. Corporations do not obtain moral purpose and a “social license” through acts of philanthropy. Corporations do not need to engage in charitable work because they have ready-made social purposes which are as great, if not greater, than any philanthropic endeavor they could participate in. Corporations contribute to society in four essential ways as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 The four social functions of the public company

IR contributes directly to shareholder value but also facilitates a wider social purpose by keeping management informed. All four of these “social functions” of the corporation rely however on profitability, and since investors are a group keenly focused on profit, communication with investors is a key task of management.

IR facilitates disclosure, dialogue, understanding, and mutual adjustment. IR helps investors to play a positive role in corporations. Investors have a unique authority based on both the information and sanctions that they have access to. Investors may be the only group that can penetrate the ivory tower of management, and their broad commitment to overall firm success distinguishes them from the many sectional interests that management engages with. Investors represent the best source of business advice that management can access. Their knowledge of competitors, industry dynamics, and macroeconomic factors can be of great value. One does not have to agree with the “shareholder value” doctrine to believe that investors have a unique status and a unique role, and IR has a special responsibility to unlock the value from the shareholder relationship.

IR is part of the oil that helps the stock market function smoothly by matching investors with appropriate companies, keeping investor expectations realistic and ensuring that management teams are aware of investor sentiment. Capitalism has proven the only economic system that can provide the living standards and liberties that citizens of advanced nations expect, and so by helping to maintain efficient and fair equity markets, IR has a vital role in facilitating the growth of wealth and economic freedom, and the human rights and democratic institutions that have been shown to develop from sustained economic growth.

The Social Purpose of IR

By keeping management compliant, helping companies avoid valuation crises, informing management of market sentiment, and contributing to corporate strategy making, IR performs a valuable service to management which has wider benefits. By helping investors with the valuation process and keeping management in touch with investor sentiment, IR is serving investors but also serving the wider market. IR plays a part in maintaining market efficiency and price stability by ensuring that accurate corporate information flows to the market quickly, and that problems with corporate performance, activity, or strategy are fed to the management team while they still have time to make improvements, or correct perceptions. IR at its best can perform a valuable function of increasing market efficiency. The perception of market efficiency provides benefit to wider society by attracting investment to the national economy, by regularizing corporate performance and dividends, and by encouraging the public to invest and thus benefit from corporate wealth directly.

IR can contribute substantial value to corporations that take it seriously, but its value is not limited by the boundaries of the firm. IR serves a purpose beyond benefiting the participants in any single transaction, important though that purpose is. IR’s benefits also flow to market participants generally and to the society beyond the stock market. IR has the potential to contribute on three levels as shown in Figure 3.2.

IR can make a contribution to the solution of three dilemmas:

1. The managerial dilemma—How can investors be satisfied?

2. The industrial dilemma—How can the asymmetry between investors and corporations be ameliorated?

3. The societal dilemma—How can national wealth be shared?

Figure 3.2 The three levels of IR contribution

The most obvious contribution that IR makes is to solve the managerial dilemma caused by the coincidence of the increase in investors’ demands for information, interpretation, dialogue, and managerial action, and the increase in the regulation and scrutiny of that same communication with investors. IR was created as a professional function in order to satisfy these demands in a compliant, equitable, and efficient manner. The second and wider contribution that IR makes is to mitigate the corporate governance problems that affect advanced capitalism, and which are worsened as the investment chain lengthens, as corporate ownership fragments, and as business models and business networks grow increasingly complex. The third and widest contribution that IR can make is at a societal level. The industrial system is not designed as a self-serving ecosystem, but has wider responsibilities to share the wealth that it generates. It does this in several ways: through taxation, through employment, through efficiencies passed on to customers through price cuts, through improvements in product quality, through dividends, and through philanthropy. The contribution that IR makes to wider society is to make investment comprehensible, attractive, and, above all, safe for all investors. By communicating accurate information to all market participants and thus encouraging long-term investment from all investors small and large, IR helps to democratize the stock market and build public support for the system of economic freedom loosely called “capitalism.”

Albert Hirschman conceived a very wide-ranging theory in 1970 in a book called: “Exit, Voice and Loyalty.” Hirschman’s basic idea is that members of social groups (whether customers, employees, shareholders, citizens, etc.) have two basic choices when their satisfaction with the group declines. They can either silently exit or else voice their concerns, in the hope of reforming the group. Which option is chosen depends on a number of factors, including exit costs, personality, feelings of loyalty, voice mechanisms etc. Hirschman developed his theory in a period when corporations were taking customer satisfaction and customer loyalty more seriously. He was one of the first economists to try to combine political and economic research methods. Economists before and since have focused on exit rather than on the process of voice, since exit is much easier to model. Organizations that want to avoid exit need to provide mechanisms for voice, whereas organizations that wish to avoid voice need to facilitate easy exit. All organizations should measure exit and voice carefully. Investors who are unhappy may use the press to voice their concerns, creating negative sentiment. Larger investors will find exiting their shareholdings difficult. An outflow of investors which is not replaced by new investors will produce a fall in the stock price. IROs therefore need to measure investor churn and investor sentiment, and take investor comments and grievances seriously before these opinions become public. IROs should facilitate private voice, survey investor sentiment regularly, and use careful marketing to ensure that new investors are comfortable with the firm’s strategy and management.

Criticisms of IR

The four main criticisms of IR are as follows: (1) IR is not necessary because the stock market has an effective pricing mechanism; (2) IR is unfair because it promotes selective disclosure and penalizes the private shareholder; (3) it is wasteful and potentially corrupting for corporate officers to focus on the share price; their role is to manage the company, and the market will take care of the stock price; (4) IR is irresponsible. Stocks should not be “promoted” since they come with no guarantees and should be a serious and rational purchase.

The first criticism is commonly leveled at IR by finance and economics academics who subscribe to the efficient market hypothesis (EMH); the view that advanced stock markets (such as the London Stock Exchange and New York Stock Exchange) are informationally efficient and that investors cannot predict the markets, and nor can corporate managers improve their stock prices with “marketing” since the markets price in all relevant information immediately. Therefore, neither investors nor managers have anything to gain by making personal contact with each other.

The second criticism is that IR uses disreputable practices to manage share prices. The line between illegal practices such as insider trading and the “earnings game” is not always clear. These practices have been around since stock markets began, and it is unfair to condemn the IR profession as being the source of these practices; indeed, responsible IR practitioners may be the best hope of eliminating this sort of behavior. The belief that private meetings between managers and analysts are unfair on private investors was behind RegFD, which was generally supported by private shareholders and opposed by institutional investors. The meetings, however, are not all about managers disclosing to the investors and analysts, but also involve managers getting rebukes, advice, and other valuable feedback from representative owners and intelligent observers. So long as the golden rule is observed that no material nonpublic information should be disclosed in a private meeting, then these meetings perform a legitimate function as a channel of mutual enlightenment.

The third criticism is often leveled at corporate officers by investors. Investors often assert that the officers’ role is to manage the business and not to value the stock, which is the role of the market. However, it is precisely the value of the chief executive officers and chief financial officers time that is one of the most powerful reasons for the existence of an IR function so that the role of the chief officers in promoting the company can be kept within strict limits. The prime factors in stock valuation are sustained corporate profitability, solid market position, and good prospects, and the markets’ expectations of this profitability will not be lessened by any amount of proactive marketing of the stock. This criticism should be taken seriously and clear boundaries set for the IR time committed by the chief officers.

The final criticism is also very valid. IR does have a sales aspect, but selling a product is not the same as “pushing” it. IR requires a sensitive and fact-based selling process. “Promoting” the stock does not mean presenting just the virtues of the product, since company officers are not authorized to act as salespeople or advisors to investors. “Promotion” means firstly getting onto the radar of the investor, and secondly, facilitating the investor’s appraisal of the company by making sure that corporate goals, corporate strategy, industry data, and evidence of executional skill are easily accessible to the investor.