The Globalization of Companies and Competitive Advantage

Introduction

This chapter considers the globalization of companies and the primary sources of competitive advantage. We begin by considering the pressures on companies to expand globally. Next, we discuss three generic strategies for creating value in a global context: adaptation, aggregation, and arbitrage.1 Finally, we consider how and why companies globalize in stages. In the first stage of globalization, companies move from a domestic to an international strategy. In the second stage of globalization, commitment to overseas markets increases, and the company adopts a global or a multidomestic strategy. Adopting a transnational strategy defines the final stage of company globalization.

Globalization Pressures on Companies

As shown in Exhibit 2.1, there are five main imperatives that drive companies to become more global: to pursue growth, to increase efficiency, to secure knowledge or talent, to meet customer needs better, and to pre-empt or counter competition.2

Growth. International expansion offers companies a chance to conquer new markets and reach more consumers, thereby increasing sales. Many industries in developed countries are maturing rapidly, thereby reducing growth opportunities. Consider household appliances. In the developed part of the world, most households own appliances such as stoves, ovens, washing machines, dryers, and refrigerators. Industry growth is, therefore, largely determined by population growth and product replacement. By contrast, in developing markets, household penetration rates for major appliances are still low compared to Western standards, thereby offering significant growth opportunities for manufacturers.3

Exhibit 2.1 Globalization pressures on companies

Extending a product lifecycle can be an important consideration in overseas expansion. Product sales generally go through four phases: launch, growth, maturity, and decline. An overseas expansion strategy can extend the cycle significantly. What is more, companies get a chance to reimagine strategic products or services they think will excel in a new market. A new, foreign market thereby allows the revitalization of products or services that may be close to maturity in other markets.

Global expansion is not just an option for large corporations. Lemonade is a New York-headquartered insurance company that offers renters insurance and home insurance policies. The company was founded in 2015 and made its initial public offering in 2020 on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). Lemonade takes a flat 25 percent fee from the premium that customers pay to cover its expenses. The company uses any amount above this fee to cover claims and make reinsurance purchases. The remaining proceeds, if any, are donated to a nonprofit organization of the customer’s choice. The distribution of proceeds is in line with its mission of “transforming necessary evil into social good.” Part of Lemonade’s appeal is that it provides insurance policies that customers feel good purchasing.

Since 2018, Lemonade has had a stated goal of expanding globally, responding to consumers’ needs that are increasingly cosmopolitan in their views. By 2020, the company was operating across the U.S. and had established toeholds in Germany and the Netherlands. To ease their transition into new countries, Lemonade introduced Policy 2.0, which is software designed to meet European consumers’ specific needs and make Lemonade’s product as plain and as simple as possible to understand and use.4

Lemonade is continuing its expansion across Europe. It is taking advantage of the fact that European countries are bound by agreements that favor business expansion on the continent. A business license facilitates the global growth that Lemonade acquired in Holland that allows it to operate in 28 other European countries.

Efficiency. A global presence automatically expands a company’s operations scale, giving it larger revenues and a larger asset base. A larger scale can help create a competitive advantage if a company undertakes the tough actions needed to convert scale into economies of scale by (1) spreading fixed costs, (2) reducing capital and operating costs, (3) pooling purchasing power, and (4) creating critical mass in a significant portion of the value chain. Whereas economies of scale primarily refer to efficiencies associated with supply-side changes, such as increasing or decreasing the scale of production, economies of scope refer to efficiencies typically associated with demand-side changes, such as increasing or decreasing the scope of marketing and distribution by entering new markets or regions, or by increasing the range of products and services offered. The economic value of global scope can be substantial when serving global customers with coordinated services and leveraging a company’s expanded market power.5

Outsourcing and offshoring are strategies aimed at reducing costs. Under an outsourcing strategy, a company contracts with a party outside a company to perform services or manufacture products traditionally created in-house. Offshoring involves relocating a business activity to another country, generally to take advantage of labor cost differentials. While outsourcing and offshoring can reduce a firm’s costs of doing business, its home country’s job losses can devastate local communities, leading to negative publicity.

Knowledge and talent. Greater cross-border competition means that there is no firm capable of staying competitive by relying entirely on its internal resources and capabilities. While accessing external resources is common to firms in all sectors, the need to collaborate with external partners—suppliers, customers, competitors, universities, or institutions—is even more evident in technological sectors. More must be done with stretched research and development (R&D) budgets, as products and services increasingly involve multiple technologies. The need for a growing breadth of competencies has raised the costs and the associated risks of new product development. At the same time, firms must innovate faster to maintain their competitiveness in the market. As a result, for many companies, technological or R&D alliances are no longer viewed as an option but as a strategic necessity. Accessing external knowledge through R&D alliances can help firms reduce time-to-market and develop new product innovations that they could not have done internally. R&D alliances also can improve the quality and efficiency of new products and processes and facilitate access to new markets.

Foreign operations can be a reservoir of knowledge. Some locally created knowledge is relevant across multiple countries and, if leveraged effectively, can yield significant strategic benefits to a global enterprise such as (1) faster product and process innovation, (2) lower cost of innovation, and (3) reduced risk of competitive preemption. For example, Procter and Gamble’s (P&G’s) liquid Tide was developed as a joint effort by the company’s U.S. employees (technology to suspend dirt in water), its Japanese subsidiary (cleaning agents), and its Belgian operations (agents that fight mineral salts found in hard water). Realizing the full potential of transferring and leveraging knowledge across borders is difficult. Significant geographic, cultural, linguistic distances often separate subsidiaries. The challenge is to create systematic and routine mechanisms to uncover opportunities for knowledge transfer.

Another major reason for going global is the opportunity to access new talent pools. In many cases, international labor can offer companies unique advantages in increased productivity, advanced language skills, diverse educational backgrounds, and more. For example, when Netflix expanded to Amsterdam, the company praised the city for enabling Netflix to hire multilingual and internationally minded employees who can expertly “understand consumers and cultures in all of the territories across Europe.”

Also, international talent may improve innovation output within a company. That is one reason why foreign markets that welcome global entrepreneurs and skilled workers often have denser and more successful startup climates.

Globalization of customer needs and preferences. Through technology and experience, individual customers have become more aware of the rich variety of products and services available worldwide and want to buy them. Global travelers insist on consistent worldwide service from airlines, hotel chains, credit card companies, television news, and others. Global companies such as General Electric (GE) or DuPont insist that their suppliers—from raw material suppliers to advertising agencies to personnel recruitment companies—also globalize their approach and serve them whenever and wherever required. These trends force companies to adapt to changing customer needs and preferences and may require them to globalize their operations.

The globalization of competitors. Just as the globalization of customer needs and preferences compels companies to consider globalizing their business model, so does the globalization of one or more major competitors. Companies may use international expansion to gain a competitive edge over their opponents. For example, businesses that expand in markets where their competitors do not operate sometimes have a first-mover advantage, allowing them to build strong brand awareness with consumers before their competitors. International expansion can also help companies acquire access to new technologies and industry ecosystems, which may significantly improve their operations.

Finally, international business can also increase a company’s perceived image. Global operations can help build name brand recognition to support future business scenarios, such as contract negotiations, new marketing campaigns, or additional expansion.

Other reasons to expand abroad include diversification and investment potential.

Countries and regions vary in terms of their stage of development, with different growth rates and potential. Companies may prefer not to concentrate all their efforts in a limited number of countries and wish to spread their risk. Such firms will look for markets that are different from those they already serve in terms of economic parameters such as growth rate, size, affluence of customers, stage of market development, and so on. Serving a portfolio of different markets can make revenues and profits more consistent and investment requirements more balanced.

Finally, companies considering international expansion should not forget about the additional investment opportunities that foreign markets can offer. For example, many firms can develop new resources and forge important connections by operating in global markets. Companies with multinational operations can sometimes benefit from lucrative investment opportunities that may not exist in their home country. For example, many governments around the world offer incentives for companies looking to invest in their country.

Mini-Case 2.1: Harley-Davidson—Globalizing to Survive6

Harley–Davidson is an American motorcycle brand with a rich history and loyal brand following. The company has traditionally focused on heavyweight motorcycles with engine displacements greater than 700 cm³ but—to remain competitive—recently has broadened its product offerings to include mid-sized and smaller motorcycles. Due to Harley-Davidson’s customers’ passion for the brand, it has successfully licensed a wide range of other products, including apparel, home decor, toys, accessories, and more.

In the last few years, the company has been challenged by changes in its primary market’s socio-cultural environment—the United States—and the legal environment internationally and domestically in the form of trade barriers. In the United States, gas-guzzling hogs are no longer appealing to younger consumers. In response, the company has (1) opened assembly plants in India to get around some of the tariffs and (2) entered Brazil to take advantage of the free trade zone. However, the company is still facing the impact of steel tariffs on U.S. imports, which has added millions to Harley-Davidson’s costs.

Harley-Davidson is also eying growth abroad. Developing countries represent an increasingly attractive opportunity as improved infrastructures in these countries allow for better distribution and motorcycles usage.

The AAA Global Strategy Framework7

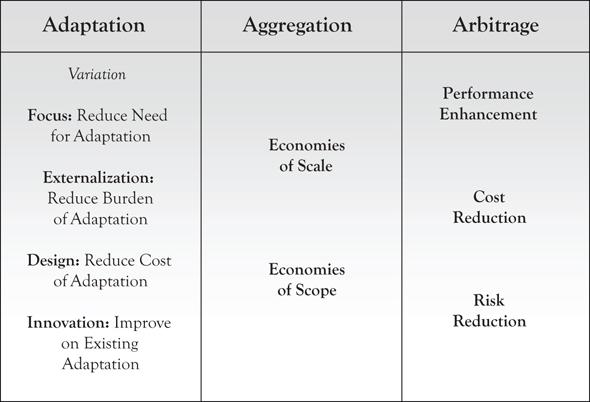

Pankaj Ghemawat offers three generic approaches to developing a global competitive advantage (see Exhibit 2.2). Adaptation strategies seek to increase revenues and market share by tailoring one or more components of a company’s business model to suit local requirements or preferences. Aggregation strategies focus on achieving economies of scale or scope by creating regional or global efficiencies. They typically involve standardizing a significant portion of the value proposition and grouping together development and production processes. Arbitrage is about exploiting economic or other differences between national or regional markets, usually by locating separate parts of the supply chain in different places.

Adaptation. Adaptation—creating global value by changing one or more elements of a company’s business model to meet local requirements or preferences—is probably the most widely used global strategy. The reason is that some degree of adaptation is essential or unavoidable for virtually all products in all parts of the world. A good example is provided by McDonald’s. This global company adapts its menus to the locations the brand is targeting. For example, there are many kosher restaurants in Israel and Argentina and halal branches in Pakistan, Malaysia, and other predominantly Muslim countries worldwide. In India, no beef or pork products are sold in deference to Hindu and Islamic beliefs and customs. Also, consider the construction adhesive industry. The packaging in the United States informs customers how many square feet it will cover; the same package in Europe must do so in square meters. Even commodities such as cement are not immune; its pricing in different geographies reflects local energy and transportation costs and what percent is bought in bulk.

Exhibit 2.2 Adaptation, aggregation, and arbitrage Adapted from Ghemawat, P. 2007. Redefining Global Strategy. Harvard Business School Press.

Adaptation strategies can have many foci, including variation, focus, externalization, design, and focus (see Exhibit 2.3).

Variation strategies involve making changes in products and services and adjusting policies, business positioning, and success expectations. For example, Whirlpool offers smaller washers and dryers in Europe than in the United States, reflecting the space constraints prevalent in many European homes. The need to consider adapting policies is less obvious. An example is Google’s dilemma in China to conform to local censorship rules. Changing a company’s overall positioning in a country goes well beyond changing products or even policies. Initially, Coke did little more than skim the cream off big emerging markets such as India and China. It successfully changed to a “lower margin—higher volume” strategy that involved lowering price points, reducing costs, and expanding distribution to boost volume and market share. For example, changing expectations with investors or partners about a particular country’s growth rate is also a prevalent variation.

Exhibit 2.3 AAA strategies and their variants

The second type of adaptation focuses on particular products, geographies, or vertical stages of the value chain, or market segments to reduce the impact of differences across regions. A product focus recognizes that wide differences can exist within broad product categories in the degree of variation required to compete effectively in local markets. Action films such as The Gentlemen or Bad Boys for Life need far less if any adaptation than local newscasts, for example. Restriction of geographic scope can focus on countries where relatively little adaptation of the domestic value proposition is required. A vertical focus strategy involves limiting a company’s direct involvement in the supply chain’s specific steps, while outsourcing others. Finally, a segment focus involves targeting a more limited customer base. Using this strategy, a company realizes that it will appeal to a smaller market segment or different distributor network from those in the domestic market, unless it modifies its products. Many luxury goods manufacturers employ this approach.

Whereas focus strategies overcome regional differences by narrowing the scope, externalization strategies transfer responsibility for specific parts of a company’s business model to partner companies to accommodate local requirements, lower cost, or reduce risk. Options for achieving externalization include strategic alliances, franchising, user adaptation, and networking. Eli Lilly, for example, extensively uses strategic alliances abroad for drug development and testing. McDonald’s growth strategy abroad uses franchising as well as company-owned stores. And, software companies depend heavily on user adaptation and networking to develop applications for their basic software platforms.

The fourth type of adaptation focuses on design to reduce costs. Manufacturing costs can often be achieved by introducing design flexibility to overcome supply differences. Introducing standard product platforms and modularity in components also helps to reduce costs.

The fifth approach to adaptation is innovation, aiming to enhance adaptation efforts’ effectiveness through cost reduction or value enhancement. For instance, IKEA’s flat-pack design, which has reduced the geographic distance by cutting transportation costs, has helped the company expand more effectively into foreign markets.

Aggregation. Aggregation is about creating economies of scale or scope as a way of dealing with differences. The objective is to exploit similarities among geographies rather than to adapt to differences. Complete standardization destroys concurrent adaptation approaches. Therefore, the key is to identify ways to introduce economies of scale and scope into the global business model without compromising local responsiveness. For example, Walmart’s economies of scale are derived from buying its merchandise in bulk, usually at significant discounts. To do business with Walmart is important to suppliers—its products are seen by millions of shoppers each day across the globe. This benefit allows Walmart to force suppliers to accept low prices to remain in its good standing.

Adopting a regional approach to globalizing the business model is probably the most widely used aggregation strategy. As discussed earlier, regionalization or semiglobalization applies to many aspects of globalization—from investment and communication patterns to trade. Even when companies have a significant presence in more than one region, competitive interactions are often regionally focused. Nestle is a good example of a company that uses regionalization. The company’s Indian subsidiary—Nestle India—has adopted a regional cluster-based approach to developing tailor-made brand, marketing, and distribution strategies to address the needs of consumers in specific geographies. The company has created virtual teams for each cluster responsible for tailor-made strategies for brands, distribution, channel strategy, marketing, and promotion relevant to each region.8 Dutch electronics giant Philips created a global competitive advantage for its Norelco shaver product line by centralizing global production in a few strategically located plants. By locating plants in each part of the triad, the company realized significant economies of scale.

Global corporate branding over product branding is another powerful way to create economies of scale and scope. A global brand is the brand name of a product that has worldwide recognition. Economies of scope are realized to the extent a brand is recognized, accepted, and trusted across borders. Some of the world’s most-recognized brands include Coca-Cola, IBM, Microsoft, GE, Nokia, McDonald’s, Google, Toyota, Intel, and Disney. As these examples show, geographic aggregation strategies have potential applications for every major business model component.

Geographic aggregation is not the only way to generate economies of scale or scope. Other, nongeographic dimensions of the CAGE framework—cultural, administrative or political, and economic—also lend themselves to aggregation strategies. For example, major book publishers publish their bestsellers in just a few languages, knowing that readers will accept a book in their second language (cultural aggregation). Pharmaceutical companies seeking to market new drugs in Europe must satisfy a few selected countries’ regulatory requirements to qualify for a license to distribute throughout the European Union (EU) (administrative aggregation).

Arbitrage. A third generic strategy for creating a global advantage is arbitrage. Arbitrage is about exploiting differences between national or regional markets, usually by locating separate parts of the supply chain in a different country. Exploiting differences in labor costs—through outsourcing and offshoring—is probably the most common form of economic arbitrage. This strategy is widely used in labor-intensive (garments) and high-technology (flat-screen TVs) industries. Another form of economic arbitrage is the exploitation of differences in knowledge. Many Western companies have established R&D and software development centers in India because of the availability of relevant talent. Finally, an arbitrage strategy can improve a company’s risk profile by spreading operations over several countries or regions.

Favorable effects related to country or place of origin have long supplied a basis for cultural arbitrage. For example, an association with French culture has long been an international success factor for fashion items, perfumes, wines, and foods, whereas Italian products connote a high level of stylishness. Similarly, fast-food products and drive-through restaurants are mainly associated with U.S. culture.

Legal, institutional, and political differences between countries or regions create opportunities for administrative arbitrage. Administrative arbitrage encompasses all the measures that companies take regarding taxes and regulations, including environmental regulations. Taxation is a major factor in companies’ geographic decisions because of the large variations in tax rates worldwide.

As globalization advances, the scope for geographic arbitrage—the leveraging of geographic differences—has been diminished but not fully eliminated. For example, air transportation has created a global flower market where flowers from favorable growing regions can be auctioned year-round in Aalsmeer, the Netherlands, and flown to customers worldwide while still fresh.

Which A Strategy Should a Company Use?9

A company’s financial statements can be a useful guide to signaling which of the A strategies will have the greatest potential to create global value. Consumer goods manufacturers with large marketing budgets use adaptation strategies to improve their market share abroad. Firms that engage heavily in R&D and have high levels of fixed costs, such as pharmaceutical companies, should consider centralizing and locating their laboratories in talent-rich, cost-effective locations worldwide. Firms that rely heavily on branding and do a lot of advertising, such as food companies, often need to engage in considerable adaptation to local markets. For firms whose operations are labor-intensive such as apparel manufacturers, arbitrage will be of particular interest because labor costs can vary greatly from country to country.

Which A strategy a company emphasizes also depends on its globalization history. Companies that start their globalization on the supply side of their business model, that is, seeking to lower cost or access new knowledge, typically focus on aggregation and arbitrage to create global value. Firms that start their globalization by exporting are immediately faced with adaptation challenges.

P&G is an example of a company that has successfully applied all three A strategies in different parts of its business model in a coordinated manner. P&G’s global business units sell-through market development organizations that are aggregated up to the regional level. It adapts its value proposition to important markets and competes—through global branding, R&D, and sourcing—based on aggregation. Its use of arbitrage—mostly through outsourcing activities invisible to the final consumer—is important to keeping costs under control and enhancing P&G’s global competitive advantage.

Moving From A to AA to AAA

From an A to AA strategy. Although most companies start by focusing on just one A at any given time, increased competition has forced companies to pursue two or even all three of the As. Doing so presents special challenges because there are inherent tensions between all three approaches. Companies focused on aggregation seek economies of scale and scope through standardization of products and processes and centralization of decision making. On the other hand, companies using adaptation strategies need to tap local knowledge and involve local creative partners in adapting their business model to suit local needs and preferences. As a result, companies seeking adaptation are less concerned with economies of scale and scope and often more decentralized. These tensions show that the pursuit of AA strategies or even an AAA approach requires considerable organizational and managerial flexibility.10

International business machines (IBM) addressed the tensions between adaptation and aggregation by using different As of the AAA framework at various points in expanding globally. The company uses adaptation to enter the various international markets it operates in—now more than 170 countries.11 Typically, IBM enters international markets by launching a mini IBM in the foreign country targeted that guides the adaptation strategy to match its customers’ local needs and preferences. Once established, it begins to look regionally for aggregation opportunities through economies of scale and scope.

Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), headquartered in Mumbai, India, successfully combined aggregation and arbitrage within its business model. The company uses an arbitrage strategy by exporting software service export to countries where labor costs are high. It has supplemented this strategy with an aggregation component by developing a new global delivery structure based on three types of software development centers. Global centers in India cater to large accounts; regional centers based in Hungary and Brazil specialize in language and cultural aspects of software support, while Phoenix and Boston centers support U.S. technology corridors with a close location.12

Developing a AAA strategy. As shown in Exhibit 2.4, organizational tensions between the three A strategies seriously constrain companies to use all three simultaneously with great effectiveness. The different A strategies are focused on different sources of competitive advantage. Two of them (adaptation and aggregation) seek to minimize CAGE effects, whereas the other (arbitrage) seeks to exploit them. The implementation of the different A strategies calls for different loci of coordination and has different organization champions. Finally, there are considerable differences associated with the strategy levers associated with each A strategy. As a consequence, attempts to implement all three strategies at the same time (1) stretch a firm’s managerial bandwidth, (2) force a company to operate with multiple corporate cultures, and (3) can create opportunities for competitors to undercut a company’s overall competitiveness. Thus, to consider an AAA strategy, a company must find ways to mitigate the tensions between adaptation, aggregation, and arbitrage.

Exhibit 2.4 Differences among the A strategies

Companies that have successfully adopted a combination of all three As typically spent years in trial-and-error mode. P&G is a good example. P&G started its global expansion with an adaptation–arbitrage strategy. The company focused extensively on locational R&D and creating autonomous mini P&G branches in each location. Meanwhile, it outsourced a certain part of the production process to cheaper locations. Later, when this localization strategy started to create too much redundancy across regions, P&G added aggregation by adopting a matrix organization structure to focus on exploiting synergies across regional business units and product lines.13

Pitfalls and Lessons in Applying the AAA Framework

As noted, the implementation of the AAA framework presents considerable challenges. As a consequence, companies should consider:

1. Focusing on one or two of the As. While it is possible to make progress on all three As, companies or business units or divisions usually have to focus on one or at most two A’s to build competitive advantage.

2. Making sure the new elements of a strategy are a good fit organizationally. If a strategy introduces new elements, companies should pay particular attention to how well they work with other things the organization is doing. IBM has grown its staff in India much faster than other international competitors such as Accenture. But quickly molding this workforce into an efficient organization with high delivery standards and a sense of connection to the parent company is a critical challenge.

3. Employing multiple integration mechanisms. The pursuit of more than one of the As requires creativity and breadth in thinking about integration mechanisms. Given the stakes, these factors cannot be left to chance.

4. Thinking about externalizing integration. IBM and other firms illustrate that some externalization is a key part of most ambitious global strategies. Externalization can take several forms such as (1) joint ventures in advanced semiconductor research, development, and manufacturing; (2) links to and support of Linux and other efforts at open innovation; (3) outsourcing of hardware to contract manufacturers and services to business partners; and (4) IBM’s relationship with Lenovo in personal computers.

5. Knowing when not to integrate. Some integration is usually good, but more integration is not always better.

Mini-Case 2.2: SoFi—Adaptation and Arbitrage at Work

Social Finance (SoFi) is an online personal finance company whose business strategy was originally centered on refinancing student education loans. Outstanding student debt in the United States had been growing tremendously, reaching 1.54 trillion U.S. dollars in early 2020. Financial technology (fintech) solutions helped meet student loan needs, explaining the industry’s rapid growth in the preceding decade. SoFi generated revenue by charging a small fee to merchants for the use of their cards, by earning interest on money in consumer spending accounts, and by selling loan packages to institutions that acted as third-party investors. The company generated over 400 million U.S. dollars in revenue in 2019 and had raised over three billion U.S. dollars in equity financing. By 2020, SoFi had acquired over a million members.

SoFi helped refinance and consolidate student loans, both federal and private. Customers applied through a simple online process, and they benefited from SoFi’s seven-day a week customer support. It allowed borrowers to defer their loans if they were enrolled at least part time in a graduate program or actively serving in the military. SoFi offered low-interest rates and enabled its customers to pay fixed amounts for their loans ranging from 5,000 to 100,000 U.S. dollars.

Customers also benefited from SoFi’s flexibility because the financial institution tried to meet their needs and make it easier for them to get the money they needed. For example, if customers lost their job, SoFi would defer their payments and even help them find a new job. In addition to loans, bank accounts, mortgages, and payments infrastructures, SoFi also provided insurance. The company offered several insurance products (life insurance, auto insurance, homeowners’ and renters’ insurance) through partnerships with several third-party insurance companies.

The typical credit score of an approved borrower or cosigner was 700 or higher. There was no minimum income required for approval, but SoFi studied the borrower’s free cash flow to determine eligibility. Generally, applicants were U.S. citizens or permanent residents, and they had graduated with an associate degree or higher.14 Nearly 400,000 graduate students had refinanced their student debt through SoFi. The company also helped them pay for graduate school, offering private student loans at a competitive rate.

SoFi’s success was particularly impressive because it was achieved after overcoming a major setback. In 2018, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed a complaint against Sofi, claiming that the company misled customers regarding how much they could save with SoFi’s services. SoFi settled with the FTC. Although it avoided paying penalties, it was barred from making any claim about how much the consumer would save that was not backed with clear evidence.

Encouraged by its profitability in fintech, SoFi reformulated its corporate strategy to diversify its offerings. Customers were increasingly drawn to SoFi for mortgages, loans, debit cards, and cryptocurrency trading. In 2020, the company announced its plan to expand globally. As a financial capital in Asia and a renowned financial center, Hong Kong stood out as a great location to start the global expansion.15 SoFi’s first move toward this goal was acquiring 8Securities, a trading platform based in Hong Kong.16 Many businesses and individuals, including investors in Hong Kong, could take advantage of the SoFi offerings. As part of the expansion plan, the company launched SoFi Invest in Hong Kong, the only investing platform that offered full access to a wide range of services, from brokerage and exchange traded funds (ETFs) to automated investing, all commission-free.

With the changes prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the global shift toward remote work, and the need for additional online-based tools, SoFi decided to expand into nonconsumer-facing services. It acquired Galileo Technologies, which provided payment infrastructure for multiple companies in the financial technology industry, such as Robinhood, Chime, or TransferWise. Galileo offered debit, credit, prepaid and virtual cards, cryptocurrency, contactless payments, mobile technology, fraud protection, and advanced analytics. Adding the company under SoFi’s umbrella broadened the array of services that SoFi offered, enabling them to capture a larger customer base. The acquisitions also supported SoFi’s plan to expand internationally while diversifying its revenue streams to reduce its investment risk.

Stages in the Globalization of Companies

Going global is often described in incremental terms as a more or less gradual process, starting with increased exports or global sourcing, followed by a modest international presence, growing into a multinational organization, and ultimately evolving into a global posture. This appearance of gradualism, however, is deceptive. It obscures the key changes globalization requires in a company’s mission, core competencies, structure, processes, and culture. Consequently, it leads managers to underestimate the enormous differences between managing international operations, a multinational enterprise, and managing a global corporation.

A domestic focus is much simpler to implement than pursuing international business objectives. Domestic operations are subject only to a domestic set of rules and requirements. Market analysis has a narrower focus when coping with fewer regions than predicting several cultures’ needs and preferences across various countries. As a result, domestic businesses can often establish and capitalize on a market niche. Domestic businesses follow the home country’s securities laws and generally construct their financial reports according to the country’s generally accepted accounting principles. Domestic businesses manage their balance sheets without considering the currency, tax regulations, and financial reporting differences of other countries like an international company would.

International business requires dealing with foreign stakeholders, employees, consumers, and governments. Therefore, managers need to consider many factors when conducting business in global markets, such as customers’ local needs and preferences, the competitive environment, supply chain management challenges, government rules and regulations, and marketing issues. To successfully expand their consumer base and increase profitability through internationalization, companies need to spend the necessary time and resources to understand global market opportunities and choose the proper international business strategies.

Doing business internationally, therefore, is different from doing business at home. New skills need to be learned and knowledge acquired about the countries a company wishes to enter. Firms need to learn about the different laws and regulations, customer needs and preferences, buying habits, and adapt their business model to appeal to the new countries they are targeting. Key differences include:

• Politics or government or legal systems. Although competing in international markets offers important potential benefits, such as access to new customers, the opportunity to lower costs, and the diversification of business risk, going overseas also presents considerable challenges. Political risk refers to the potential for government upheaval or business interference. For example, the term Arab Spring has been used to refer to a series of uprisings in 2011 in the Middle East. Political instability makes it difficult for firms to plan for the future. Over time, a government could become increasingly hostile to foreign businesses by imposing new taxes and new regulations. In extreme cases, a firm’s assets in a country are seized by the national government. For example, in recent years, Venezuela has nationalized foreign-controlled operations in the oil, cement, steel, and glass industries. Countries with the highest levels of political risk tend to have governments that are so unstable that few foreign companies are willing to enter them. That said, high levels of political risk are also present in several of the world’s important emerging economies, including India, the Philippines, Russia, and Indonesia. The dilemma for firms is that these high-risk countries also offer enormous growth opportunities. Finally, no two countries have the same political and legal systems. Each government has its policies related to the presence of foreign firms and products. The key is to understand that once a company enters a foreign market, it must abide by the country’s rules and laws, not the ones in its home market. These laws and regulations can severely impact the potential long-term success of a business.17 18

• Cultures. Cultural risk refers to the risks posed by differences in language, customs, norms, and customer preferences. The history of business has many examples of cultural differences that undermined companies. For example, a laundry detergent company was surprised by its poor sales in the Middle East. Executives believed that their product was promoted using print advertisements that showed dirty clothing on the left, a box of detergent in the middle, and clean clothing on the right. However, unlike English and other Western languages, the languages used in the Middle East, such as Hebrew and Arabic, involve reading from right to left. To consumers, the implication of the detergent ads was that the product could be used to take clean clothes and make them dirty. As this example shows, understanding both the social and business culture in another country is key to success. Therefore, it is important to include research on the country’s culture (s) a firm intends to sell before entering the market.19

• Level and nature of competition. The level of competition a company will experience in foreign markets is likely to be more dynamic and complex than in domestic markets. Competition may exist from various sources, and the nature of competition may change from country to country. Competition may be encouraged or discouraged in favor of cooperation, and buyer–seller relationships may be friendly or hostile. When companies compete for access to the latest technology, the technological innovation level can be an important aspect of the competitive environment.

• Transportation infrastructure and media. Business infrastructure in foreign markets is likely to be at different levels of development. This can impact a firm’s ability to get products to market. It is important to research a new target market and understand how goods are moved within the country before a company commits to that market. If advertising and promotion are critical components of a firm’s business model, it is important to know the types of media available and the kinds of media the target market uses to gain information about products and services offered. In many regions of the world, only a limited number of potential customers are connected to the Internet, and not every customer can read and write. This means firms need to research the most appropriate media for the chosen target market.

The Bartlett–Ghoshal Matrix

A frequently used framework to distinguish between four types of international companies is the Bartlett and Ghoshal matrix. It characterizes firms based on two criteria: global integration and local responsiveness (see Exhibit 2.5). Businesses that are highly globally integrated seek to reduce costs as much as possible by creating economies of scale through a more standardized product offering worldwide. Companies that are locally responsive seek to adapt products and services to specific local needs. Although these strategic options appear to be mutually exclusive, some companies are trying to be both globally integrated and locally responsive. Together, these two factors define four types of strategies that internationally operating businesses can pursue: international, multidomestic, global, and transnational strategies.20

Exhibit 2.5 Bartlett–Ghoshal matrix

International companies. An international strategy is focused on exporting products and services to foreign markets or importing goods and resources from other countries for domestic use. Companies that employ an international strategy are often headquartered exclusively in their country of origin and typically do not invest in staff and facilities overseas. However, this model is not without significant challenges, like establishing sales and administrative offices in major cities internationally, managing global logistics, and ensuring compliance with foreign manufacturing and trade regulations.

As shown in Exhibit 2.5, international companies typically operate with a low degree of integration and local responsiveness. Firms that mainly export or license have little need for local adaption and global integration. Products are produced in the company’s home country and shipped to customers all over the world. If subsidiaries operate, they function more like local channels through which the products are being sold to the end-consumer.

An international strategy may be the most common strategy because it requires the least amount of overhead. As a company’s globalization develops further, many international companies evolve into multidomestic, global, or transnational companies. The international model is unsophisticated and unsustainable if the company further globalizes and therefore is usually transitory. In the short term, this organizational form may be viable when the need for localization and local responsiveness is very low. The potential for aggregation economies is also low. Large wine producers are good examples of international companies.

Multidomestic companies. For a business to adopt a multidomestic business strategy, it must establish its presence in one or more foreign markets and tailor its products or services to the local customer base.

In moving from an international to a multidomestic strategy, a business typically starts by establishing a presence in one or more foreign market(s) and adapting its products or services to a local market. As opposed to marketing foreign products to customers who may not initially recognize or understand them, companies modify their offerings and reposition their marketing strategies to meet local needs and preferences. A complicating factor is that they may need distinctive strategies for each of these markets because customer demand and competition are different in each country. Competitive advantage, therefore, is determined separately for each country.

Multidomestic businesses usually keep their company headquarters in their country of origin. Often, they establish overseas subsidiaries, which are better equipped to offer foreign consumers region-specific versions of their products and services. Multidomestic companies typically employ country-specific strategies with only modest international coordination or knowledge transfer from the central headquarters. Each country subsidiary typically makes key decisions about local strategy, resource allocation, decision making, knowledge generation, transfer, and procurement with little value-added from the corporate headquarters. Consequently, the pure multidomestic organizational structure ranks high on local adaptation and low on global aggregation. Like the international model, the traditional multidomestic organizational structure is not well suited to a globally competitive environment in which standardization, global integration, and economies of scale and scope are critical. However, this model is still viable in situations where local responsiveness, local differentiation, and local adaptation are important. There are limited opportunities for global knowledge transfer, economies of scale, and economies of scope. As with the international model, the pure multidomestic company sometimes represents a transitory organizational structure.

Multidomestic strategies are frequently used by food and beverage companies. For example, the Kraft Heinz Company makes a specialized version of its ketchup for customers in India to match the nation’s preferences for a different blend of spices. However, these adjustments are often expensive and can incur a certain financial risk level, especially when a company wishes to launch unproven products in a new market. Companies, therefore, only utilize this expansion strategy in a limited number of countries.

Global companies. Companies following a global strategy seek to leverage economies of scale to boost their reach and revenue. Global companies attempt to standardize their products and services as much as possible to minimize costs and reach as broad an international customer base as possible. Global companies tend to maintain a central office or headquarters in their country of origin while also establishing operations worldwide. Pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer can be considered global companies.

Even when they try to keep essential aspects of their products and services intact, companies using a global strategy typically have to make some practical small-scale adjustments to penetrate international markets. For example, software companies need to adjust the language used in their products. By contrast, fast-food companies may add, remove, or change the name of certain menu items to suit local markets better while keeping their core items and global message intact. Thus, a traditional global company is the opposite of a traditional multidomestic company. It describes companies with globally integrated operations designed to take advantage of economies of scale and scope by the following standardization and exploiting global efficiencies.21 By globalizing operations and competing in global markets, these companies aim to reduce cost—in R&D, manufacturing, production, procurement, and inventory. They also seek to enhance customer preference through global products and brands and obtain competitive leverage. Key strategic decisions are typically made at corporate headquarters. In the global aggregation or local adaptation matrix, the pure global company scores high on global aggregation (integration) and low on local adaptation (localization).

Transnational companies. A transnational business strategy can be seen as a combination of global and multidomestic strategies. Typically, a transnational company keeps its headquarters and core technologies in its country of origin, but also considers allows establishing full-scale operations in foreign markets. The decision-making, production, and sales responsibilities are evenly distributed to individual facilities in these different markets, allowing companies to have separate marketing, research, and development departments to respond to local consumers’ needs.

A transnational company aims to maximize local responsiveness but also to gain benefits from global integration. Even though this appears contradictory, this is made possible by considering the entire whole value chain. Transnational companies often seek to create economies of scale upstream in the value chain and use more locally adaptive approaches in downstream activities such as marketing and sales. In terms of organizational design, a transnational company typically has an integrated and interdependent network of subsidiaries worldwide. These subsidiaries have strategic roles and act as centers of excellence. Because of efficient knowledge and expertise exchange between subsidiaries, a transnational company can meet both strategic objectives.

A transnational company’s biggest challenge is identifying the best management tactics for achieving positive economies of scale and increased efficiency. Having many inter-organizational entities collaborating in dozens of foreign markets requires a significant start-up investment. Costs are driven by foreign legal and regulatory concerns, hiring new employees, and buying or renting offices and production spaces. Therefore, this strategy is more complex than others because pressures to reduce costs are combined with establishing value-added activities to gain leverage competitiveness in each local market.22 Larger corporations—such as Unilever, GE, and P&G—employ a transnational strategy to invest in research and development in foreign markets and establish production, manufacturing, sales, and marketing divisions in these regions.

The Extended Bartlett–Ghoshal Matrix

Given the limitations of each of the aforementioned strategies in terms of either their global competitiveness or their implementability, many companies have settled on hybrid strategies that are more easily managed than the pure transnational model but still target the simultaneous pursuit of global integration and local responsiveness. Two of these have been labeled modern multidomestic and modern global models.

Exhibit 2.6 shows that the modern multidomestic model is an updated version of the traditional (pure) multidomestic model, including a more significant role for the corporate headquarters. Its major characteristic is a matrix organizational structure focusing on operational decentralization, local adaptation, product differentiation, and local responsiveness. The resulting model, in which national subsidiaries have significant autonomy, allows companies to maintain their local responsiveness and their ability to differentiate and adapt to local environments. Simultaneously, in the modern multidomestic model, the center is critical to enhancing competitive strength. Whereas the subsidiary’s role is to be locally responsive, the center’s role is to enhance global integration by developing global corporate and competitive strategies. The center is also actively involved in resource allocation, selecting markets, developing strategic analysis, mergers, and acquisitions, decisions regarding R&D and technology matters. An example of a modern multidomestic company is Nestlé.

Exhibit 2.6 Extended Bartlett–Ghoshal matrix

The modern global company is rooted in the traditional global form but gives a more significant role in decision making to the country’s subsidiaries. Headquarters is focused on creating a high level of global integration by pursuing low-cost sourcing options, opportunities for global scale and scope, product standardization, and global technology sharing. Modern global companies operate with an explicit, overarching global corporate strategy. But unlike the traditional (pure) global model, a modern global company makes more effective use of its subsidiaries to provide local responsiveness. As traditional global firms evolve into modern global enterprises, they tend to focus more on strategic coordination and integration of core competencies worldwide. Protecting home country control becomes less important. Modern global corporations may disperse R&D, manufacture and production, and marketing around the globe. This helps ensure flexibility in the face of changing factor costs for labor, raw materials, exchange rates, and hiring talent worldwide. P&G is an example of a modern global company.