Progress of Sustainability and Sustainability as Progress

Introduction

Only 50 years ago, United States elected officials enacted sweeping laws to protect endangered species (1969), water (1972), and air quality (1975–1990), and established the U.S. EPA (1970). To support the emerging rules, technical training in environmental fields grew, accelerating the advancement of science. During this same era, new academic disciplines, such as earth systems science and ecology, rapidly developed (Worster 1994). Later, academic fields began to integrate studies of the environment with societal and economic concerns. As examples, political ecology gained traction in the 1980s (Robbins 2004), while ecological economics (Røpke 2004) and industrial ecology (Erkman 1997) took shape in the 1990s. Beyond these new sciences, an important and profound postindustrial environmental consciousness emerged. This growing consciousness is consistently demonstrated in public opinion polls that show approximately two-thirds of U.S. adults state that environmental quality should be a priority, and the numbers are even higher among younger Americans (Funk and Kennedy 2020).

Despite this new environmental consciousness, much work remains in developing ways of thinking and scientific agendas that simultaneously address the needs of today and tomorrow. It is imperative that we engage in research that allows us to better understand how our actions affect human bodies, social systems, and ecosystems. As a broad vision, sustainability and sustainability sciences have been characterized as a new version of this needed progress (Peterson 1997). This version of progress focuses on designing human systems, so humans and other life will flourish on Earth forever (Ehrenfeld 2008). It involves changing ways of thinking to consider the interrelations among environmental, social, and economic systems, then changing our behaviors to abandon patterns that lead to decline in the quality of those systems.

We end our introduction to sustainability with a few brief discussions that we hope will lead you to consider your role in moving sustainability forward. In this chapter, we discuss two ways of thinking about sustainability agendas, the role of sustainability science, the role of people operating as engaged citizens, and the need for flexibility and steadfastness as dual elements of moving forward.

Thin and Thick Sustainability

The broadest vision of progress within sustainability calls on us to improve the quality of human life and environmental quality, all while improving the quality of both for future generations. This expansive vision, which implies moral obligations that easily garner widespread support, is described as thin sustainability (Miller 2013). Thin sustainability is a big notion. It is large enough for people to imagine how their businesses, skills, or desired futures belong within a sustainability agenda. People can easily rally around thin sustainability. As a broad concept, it is effective for gathering diverse people for a shared purpose. However, thin sustainability is commonly criticized as being too broad to translate into substantive action. The conceptual expansiveness of thin sustainability leaves subscribers with no agreed-upon definition, no substantive and specific meaning that prescribes particular actions. Thin sustainability visions are good for motivating conversations and mustering people toward a general mindset, but in order to roll up our sleeves and begin to make changes, a more detailed and nuanced, or thick, vision of sustainability is needed.

Thick sustainability is specific. It focuses on specific problems and specific system interactions. It is located in a place and is a product of persons who are local residents, who make their homes and businesses in that environment (Miller 2013). Thick sustainability works toward building a concrete, site-specific vision for sustainability agendas that will make a difference in a particular environment for a distinct set of people. By focusing attention on a refined perspective of a system and its problems, a community can design explicit actions. Pursuing thick sustainability begins when the community accepts and examines the complex interactions among its social, environmental, and economic systems. Thick sustainability proceeds, then, to shape human behaviors to improve the functioning of specific systems.

This book introduces sustainability notions through the telling of system interactions within a specific watershed, and our discussions were informed by the voices of community members who live in this large river valley in the arid American West. The examples in this book demonstrate how broad notions, thin sustainability, allow diverse interests to generally agree upon some paths forward. However, the examples also illustrate that identifiable problems can only be addressed when visions of sustainability emerge in context, specific to a place, its ecological systems (riparian cottonwood forests and sturgeon fish habitat), climate–hydrology systems (precipitation patterns and flood and drought cycles), and the societies, rules, and economies available for living there (farming, recreation, oil and gas extraction, and water rights). Engaging in business and community development that is sustainable emerges when we develop thick visions of sustainability, such as examining specific human and environmental system interactions associated with floods, flood control, cottonwood forests, and societal demands for residential, municipal, and agricultural development.

On the Yellowstone River, the CEA, with its biophysical, economic, social, and cultural data analyses, accomplished the first stages of providing thickly detailed background information needed for decision making. Important work remains to be done as the people of the Yellowstone River Valley move from thin to thick sustainability perspectives and as they begin to address pressing sustainability challenges meaningful to particular river reaches and the entire valley. It is here, at this juncture in the story of the Yellowstone River Valley, where sustainability science can be of help.

Sustainability Science

Researchers working in international development in the 1990s recognized that to deal with complex intertwined problems, they needed scientific approaches that combined the natural and social sciences. In applied academic fields addressing sustainability, traditional disciplines were tending to become more interdisciplinary to address problems in the systems in which they worked (Kajikawa, Saito, and Takeuchi 2017). A new field of research and university education, sustainability science, emerged. This new area of study used a broad array of university research areas to develop novel approaches for addressing pressing sustainability challenges. Beyond advancing disciplinary knowledge, the aim of sustainability science is to solve problems (Kates et al. 2001). Sustainability science research examines the interactions between natural and social systems and how those interactions affect the challenges of sustainability: meeting the needs of present and future generations, while substantially reducing poverty and conserving the planet’s life support systems (National Research Council 2011).

Two principles guide sustainability science. The first is that to address complex problems, interdisciplinary teams of social and natural scientists must work together to create detailed understandings of human– environmental systems. Second, the knowledge generated by these teams should lead to actions that move communities toward improving the projected long-term health of their local systems (Wiek et al. 2012). For such knowledge to be actionable, members of local communities must be consulted as experts of their home systems. Local communities must be actively involved in designing the improvements. As illustrated throughout the book, long-term residents know what has been tried in the past. They know what ideas will be rejected by their neighbors. They know who to talk to and who must be involved for any decision-making process to be successful. Problems cannot be successfully addressed by outsider experts unless they engage local communities.

Role of People as Engaged Citizens

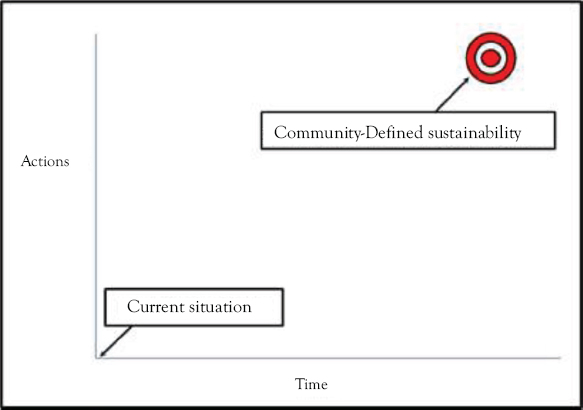

Sustainability is not a static destination but, rather, a moving target. It requires a community to develop a vision for themselves and for future generations that acknowledges change as a fundamental and necessary dynamic in the local environment. Local people must embrace being adaptive, especially in the face of unforeseen challenges. Their vision determines which actions are needed now, and which actions can be postponed. Groups of residents and leaders must define what matters to them based on context, resources, and people (Norton and Thompson 2014). Sustainable behaviors are the behaviors that help the community get from the current state to their stated community-defined vision of thick sustainability (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Thick sustainability is a community-defined goal. The actions needed are those that get a community from the current situation to its vision of sustainability

Thick sustainability is a community-defined goal. The actions needed are those that help move a community from its current situation toward its vision of sustainability.

Sustainability scientists, and other outside experts, can make worthwhile contributions to helping communities reach their sustainability goals; however, this kind of input from outsiders must be accompanied by an understanding of complex systems (including the specific systems in place within the community in question) and the ability to explain complexity in ways that help communities understand their functioning within these systems. Once clear about the specific needs faced by a community, the local community members can develop community-defined goals that are specific to place, local economies, local values, and local ambitions. Then, while still working with outside experts, the community can identify paths for achieving their sustainability goals. These efforts require coordination and good listening, especially among business and community leaders, researchers, and governmental officials. Outside experts can help local groups understand technical parts of the system for orienting to their goals, but the community must actively define their goals, navigate local terrains (physical, cultural, and political), and help make necessary course corrections. Any proposed rules, or changes to rules, must be meaningful to those expected to follow them.

The Yellowstone CEA is an example of an integrated research effort, made up of both outsider experts and insider community participants, designed to better understand a complex system. Although the research was conducted in a traditional piecemeal fashion (e.g., wildlife biologists inventoried birds and hydrologists assessed floodplain condition), the CEA constitutes a clearinghouse of the biological, hydrological, and geomorphological past and current conditions along the river. The data include the Yellowstone River Physical Features Inventory and the YRCI, both which help document the activities, goals, and desires of the people of the valley in terms of past and present individual, familial, and community perspectives.

Now that the reports are filed, we have a much better understanding, from a scientific perspective, of the river, its functions, systems, and people. Few communities have access to this level of environmental and social data. Moreover, the data, and researcher’s interpretations of that data, are freely available to the public. The Montana DNRC and the YRCDC have ensured public accessibility of the data, both in terms of physical access and ease of understanding. Decisions concerning how to best use this knowledge to shape behaviors, to reflect locally held values and desired futures, is the work of communities. Whether they call this work sustainability or not does not matter. What matters is that the community is taking steps toward developing the community-defined visions of sustainability necessary for valley communities to enhance their resilience in the face of current and unforeseen changes—but there is still much work to be done.

What to Keep and What to Let Go?

In Chapter 5, we discussed how resilience is the capacity of a natural system or human community to be able to withstand a disturbance and remain viable with its key elements intact. With each disturbance, a resilient system does change, but it retains its core identity. Knowing what we know now from the CEA, the work of building resilience of resource-dependent livelihoods in an ever-changing (dynamic) system like the Yellowstone River Valley requires difficult conversations and tough decisions about what behaviors best fit the specific social and ecological realities of the valley and which behaviors no longer work (or never worked).

Daniel Lerch (2017) writes that building resilience involves “intentionally guiding a system’s process of adaptation so as to preserve some qualities and allow others to fade away, all while retaining the essence—or identity—of the system” (5). Identity is determined by humans in terms of what they value and where they live. Local people are always the heart of planning for resilience. In the Yellowstone River Valley, because agriculture, recreation, real estate, and tourism depend on the river, local people must come together to colead conversations with civic leaders about what qualities of valley life should be preserved and which land-use practices should be allowed (encouraged) to fade away. Sustainability involves making hard choices about what behaviors need to be kept and which ones should be abandoned because they are no longer relevant to the changing systems we live within.

The CEA reveals how some land-use behaviors in the Yellowstone River Valley are outmoded when examined in light of what the residents themselves have stated they appreciate and wish to preserve. For example, bank stabilization projects (e.g., rip-rap) have a cumulative impact on fish habitats. Thus, projects that fail to meet the community’s priorities, based on current understanding of the complex interactions in the system, should be replaced with ones that do. Rather than just addressing the immediate and single-priority impacts (e.g., preventing river meanders), projects should be designed to identify and account for systemwide impacts (e.g., riparian function, cottonwood forests, fish habitat, fishing and guiding livelihoods, and tourism industry). The CEA also reveals how other behaviors need to be reconfigured if the river is to remain a vital element of valley residents’ lives. It is at the intersection of articulated community values and scientific evidence where working together, challenging conversations, and hard choices occur.

Changing behaviors is arduous. Encouraging voluntary compliance requires a lot of educating. Alternatively, policy—legal rule changes—may be an easier route for communities to take to ensure that any behaviors misaligned with the community’s values fade away. Laws are mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon (Hardin 1968). Environmental laws manage human behaviors. They are administered through incentives (carrots) to comply with agreed-upon behavior changes or through punishment, such as fines, for noncompliance (sticks). Laws often cover large geographical spaces, like a U.S. state or a river valley, and are generally accompanied by the resources of government and technical expertise to administer the incentives or fines. Policies for shared resources, like those of the Yellowstone River, are where values and science must meet. We must be willing to adopt new behaviors and rules, and we must be willing to abandon notions that prohibit us from achieving our goals.

Our task is to figure this out: what do we keep, and what do we let go? If yesterday’s thinking led to today’s problems, then repeating yesterday’s thinking may not help us find the solutions we need. Our taken-for-granted behaviors and logics should be examined and, perhaps, wholly abandoned if we intend to protect resources such as water, air, and biodiversity for future generations. Sustainability’s success depends on understanding the complexity of our systems, the interrelatedness of our problems, and the core identities of our communities. This is the ambition of sustainability and the science of sustainability. There is tremendous opportunity for individuals, businesses, and society to contribute to building more sustainable communities and natural systems. Please, go, help shape our future.

Discussion Questions

1. How can we use sustainability science to inform a local public?

2. Who must be engaged for a local community to move toward a coherent and thick vision of sustainability?

3. How might current views concerning ecosystems forestall a thick sustainability agenda?

4. How might current views concerning local economies forestall a thick sustainability agenda?

5. How might current views concerning fairness forestall a thick sustainability agenda?

6. In complex systems, how do we begin to organize policy decisions?

7. How would you define the needed philosophies that businesses, communities, and governmental entities must adopt if they hope to encourage thick sustainability?

8. How do you define your role in helping your community develop a thick sustainability agenda?