Sustainability and the Yellowstone River Valley

Figure 1.1 The Yellowstone River in October, Paradise Valley

Introduction

Local tribes called it the Elk River, and when Sacajawea helped William Clark explore the Yellowstone River Valley in 1806, his journal notes regularly mention the abundant wildlife and the “handsome” islands covered with cottonwood trees. Today, one can still recognize the valley in Clark’s descriptions. Wildlife, islands, and cottonwood forests are still, easily, found. Yet, the valley is not as it once was, and as we demand more from its resources, we begin to wonder if the river we know will be recognizable to future generations.

Using the iconic Yellowstone River Valley of Montana, United States, as the case setting (Figure 1.1), this book examines how the basic elements of sustainability manifest in real-life situations. The case demonstrates how economic, environmental, and social concerns are threaded together in a regional context, and it highlights the challenges that organizations, industries, and communities face when they imagine their long-term futures. The case also intersects with the interests of two of Montana’s American Indian tribes—the Crow and the Northern Cheyenne peoples of southeastern Montana.

This book contains elements of widely ranging aspects of sustainability issues that different readers will find useful. Readers interested in the long-term profitability of businesses and industries will find the discussions of agriculture, tourism, and oil and gas industries of interest. Readers interested in natural resource management will appreciate the discussions of the endangered Pallid Sturgeon, cottonwood forests, and riparian areas. Other readers might be drawn to the details concerning water rights and the potential environmental justice issues that permeate management decisions involving shared resources. Regardless of your initial reasons for reading about this case, the study is designed to help you recognize the many interacting dynamics of sustainability issues.

Moreover, each of us lives in a watershed, and every community is dependent on the water resources of its region. Hopefully, the Yellowstone River Valley helps you recognize similar or parallel concerns in the watershed where you live. We encourage you to use this case study as an outline for thinking about and exploring the many regional and local sustainability issues in your backyard. This case can also serve as a platform for further exploration of multiple practical, theoretical, and scientific issues.

Sustainability’s Central Question

We begin here, in Chapter 1, by discussing sustainability’s central question and the traditional approaches to addressing sustainability issues. A sustainable practice is one that we know we will need to continue in the future, so we engage in our activities in ways that allow the practice to go on in perpetuity and in ways that will not jeopardize the needs of future generations (Jenkins 2016). Thus, sustainability’s central question is this: Can we meet our current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs? To answer the question, we must anticipate and understand the potential impacts of any action on our social and ecological systems. Sustainability involves maintaining and improving the healthy functioning of our human and environmental systems to enable future generations to live on this planet.

A classic example to consider toward understanding the concept of sustainability is logging. If we go into the forest and cut down all the trees, we end logging as a practice for the foreseeable future. Even if we replant seedlings, it will take many years to again have trees to harvest. Sustainable logging means harvesting a certain number of trees each year, purposefully replanting with seedlings (or ensuring sufficient seed sources from remaining trees), and allowing some trees to grow to maturity. When logging is approached in this manner, we can harvest some trees each year, and we can repeat this process indefinitely. That said, we must be careful to attend to all the factors and changes that might influence our calculations regarding how many trees to take and how many to replant each year. Factors such as adhering to legal and industry best practices to minimize effects of harvesting on soil erosion, streams, and aquatic animals must be incorporated. Knowing how to define such factors and changes is more and more difficult (Schweier et al. 2019). Also, consider how surprise factors, such as an unforeseen beetle infestation or a prolonged drought, would change our calculations. These complex interactions among human, environmental, and economic components need simultaneous consideration for societies to move toward sustainability.

As a second example at a larger scale, we can think about the world’s fisheries: Are we treating fisheries in ways that will sustain fishing into the future? Or are we harvesting so many fish that many of our fisheries will collapse? And once the fisheries collapse, will they be gone forever? As noted by the United Nations, 59 percent of the world’s fisheries are harvested at a maximally sustainable rate, while 35 percent of the world’s fisheries are overfished and in danger of collapse (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2020). With only 6 percent of our fisheries offering room for expanded harvests, we are seemingly on the cusp of a sustainability crisis concerning the world’s fisheries. More broadly, we might think about the many other ways that we (mis)use our oceans. Are our methods of cleaning up oil spills sufficient? Is our practice of allowing plastics to enter the oceans sustainable? Will future generations inherit oceans that are in worse condition than they are in today, or might those generations thank us for passing forward oceans that are clean and productive?

When there were not so many people on Earth, perhaps it was not so important to think about the limits of environmental resources. However, for at least 30 years, and especially now that we are approaching 10 billion people on Earth, the resources needed to sustain human life are looking scarce (Daily and Ehrlich 1992). These scarcities will, and already do, cause us to ask ourselves if we dare take everything we want and assume that the next day we can do so again. There simply may not be that many trees or fish in the world.

Underlying the central question of sustainability is an implicit charge to examine our practices willingly and critically. We need to understand if we can meet our current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. If our current practices will last only over our lifetime, even though we may be satisfied, we are not operating in a sustainable manner. A long-standing and key notion in sustainability is an ethical one (Shearman 1990) that assumes we understand we should leave this Earth, our planet, our home, in good condition for the next generations (Figure 1.2). As a minimal ethical requirement, we are asked to stretch our time horizon well beyond our current interests and to consider how our current practices define the future. Sustainability represents a shift in thinking from short-term gains to long-term security rooted in continuity and certainty. What will we leave for future generations? Will they continue as we have? Might we provide them with even better circumstances than were provided to us? What parts of our societies, businesses, and environments should we bolster to ensure future generations can flourish? How must we shift our thinking and behaviors?

Figure 1.2 Visitor photographing a bison near the Yellowstone River

Sustainability’s Essentials: Economic, Environmental, and Social Well-Being

Traditionally, three areas of well-being, sometimes referred to as the “Three Pillars of Sustainability” (Beattie 2019; Purvis, Mao, and Robinson 2019), were identified as areas of concern to sustainability theorists, advocates, and managers. Today, we imagine the three areas as interconnected; however, much of the early work in sustainability studies tended to focus on one area or another. It is useful, still, to begin understanding sustainability by way of the traditional areas of well-being.

The first area for consideration is our economic well-being: Are the economic practices of today ones that will continue? If not, what are the changes in our practices that we should be discussing, and moving toward, so that future generations will also enjoy economic well-being? Are we creating industries and places where people want to work and live?

The second area of well-being is the environment. Here, we think about how we are using and interacting with the environment, and we ask ourselves, “Is this sustainable?” Are the ways we are using our water supplies sustainable? Are our practices regarding air quality sustainable? Are we slowly undermining ecosystems’ ability to support wildlife and human life? Or are we degrading our environment and our natural resources to the point that we are leaving little or nothing for future generations? Are we simply leaving them a host of environmental messes and problems?

The third area of concern is social well-being. Here, we ask ourselves, “Are we creating, or operating within, a system that is fair to everyone?” Is it equitable? Or are we shifting some people into a class of disadvantages from which they cannot escape? Are we shifting resources in ways that the social well-being of future generations is at risk? Are our practices fair to different groups of people both in the present and in the future?

As we examine our practices and consider our alternatives, we should not expect to find simple solutions or remedies. Rather, we must be ready to meet the challenge of protecting the future. We are ready for a new generation—a generation of sustainability advocates and business leaders who are willing to think critically about our current practices and who will advocate for change (Robison 2019).

The Yellowstone River Valley: An Overview

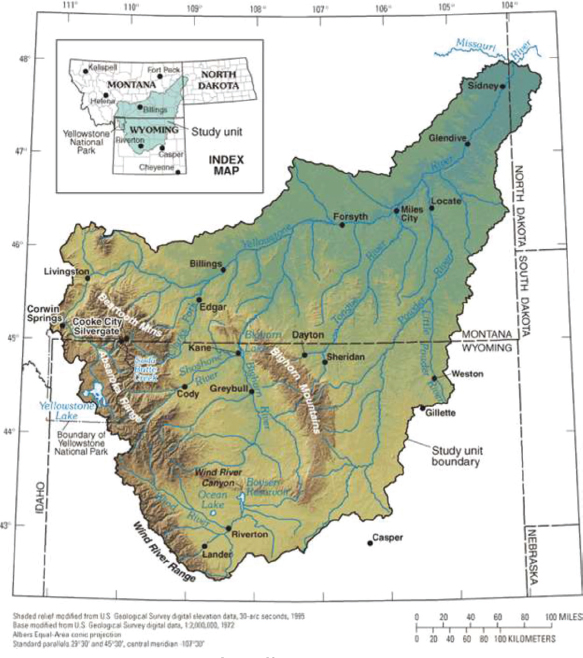

The region selected for this case study is the Yellowstone River Valley (Figure 1.3). Approximately, half of the basin is in Wyoming, and the Yellowstone River itself begins there. Many people think of the Yellowstone River as beginning at Lake Yellowstone, in Yellowstone National Park (YNP). Indeed, from the historic Fishing Bridge in the Park, you can stand over the river as it flows out of the northern end of the lake. Technically, though, the Yellowstone River begins as merely a stream in the mountains that flank the southern end of the lake. When it exits the north end of the lake at Fishing Bridge, it is a substantial river. One wonders, how does that happen? Where does such an increase of water volume originate? Put simply, there are several sources of water coming into the lake from other streams and from some 640 thermal vents under the lake (Yellowstone National Parks Trips 2017). Thus, at the outlet from Yellowstone Lake, the Yellowstone River has much greater volume than it has entering the lake (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 USGS map of the Yellowstone River Basin

Figure 1.4 The Yellowstone River Flowing from Yellowstone Lake in Yellowstone National Park

The Yellowstone River passes through three states, and with over 70,000 square miles (18M hectares) of land, its watershed is one of the largest drainage areas of the United States (Miller and Quinn n.d.). All the major tributaries to the Yellowstone River begin in Wyoming, and they flow north. They include the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River, the Bighorn River, the Tongue River, and the Powder River. For the most part, the entire drainage area flows, and the Yellowstone River flows north and east. The river flows into Montana at the northern border of Yellowstone Park at the town of Gardiner. From there, it flows over 600 river miles (965 km) across southern and eastern Montana. It continues for approximately 17 miles into North Dakota before it reaches its confluence with the Missouri River.

An interesting side note concerns the confluence in North Dakota. When Lewis and Clark came up the Missouri River in 1805, they camped at this confluence. They had to decide which of the incoming flows was a continuation of the Missouri River and which incoming flow was a tributary. Men were sent upriver, both to the northwest and to the southwest. Eventually, based on less-than-definitive reports, they decided that the branch of the river continuing to the northwest was the Missouri River. Today, we refer to this northern branch as the Upper Missouri. However, we normally consider a tributary to be a lesser river—one that contributes to a larger river. Interestingly, we now know that at the confluence, the two branches are essentially equal. One senior project manager with the Army Corps of Engineers (COE) explained that, “if we were to choose the continuation of the Missouri River, today, it would be a coin toss” (Greg Johnson, personal communication, July 02, 2020). In other words, we might rightly refer to the southern branch—the river we call the Yellowstone—as the Missouri River.

Our case study begins at the border town of Gardiner, Montana. Inside YNP, the river is managed by park officials, and decisions are in accordance with park purposes and values. The river is managed very differently once it comes out of the park and begins to intersect with private property. Indeed, beyond the park boundaries, over 80 percent of the riverbank is privately owned (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Yellowstone River Conservation District Council 2015, 4). We will look closely at what happens to the river outside the park where federal, state, and local authorities attempt to balance managing the public resources of the river with lawful private interests.

Also, much of this case study will focus on the practices of the people living near the river, or what is referred to as the main stem corridor of the river. It is in this area where most of the people live, where the most profitable economic activities occur, where environmental resources are most extensively used, and where some of the most complex social dynamics exist.

This case study examines the activities of the people and communities along the river corridor itself. Across 11 counties in Montana and one in North Dakota, the primary towns discussed in this case study include Gardiner, Livingston, Billings, Forsyth, Miles City, Glendive, and Sidney. Many of the other towns and communities along the river are strikingly small, with populations of only a few hundred people. Some of the smaller communities have only a few streets, or even just one paved (or sometimes unpaved) main street. Of course, other people live in the valley; however, those numbers are small and add only a few thousand to the total populations of each county. Unsurprisingly, many of the people living in this region embrace rural identities, and the region is generally characterized by rural activities. The largest city in Montana is Billings, with more than 100,000 people, and it is the only example of a rural/urban interface in the valley (U.S. Census Bureau 2019b).

Each of these towns and communities depends on the Yellowstone River for their physical and economic well-being. For instance, they all get their drinking water out of the river or from wells that are dependent on subsurface river flows. They also, eventually, allow much of their treated wastewater to reenter the river, often quite directly. That means the farther downstream a person is, the more times their water has recycled through different towns and different systems of drinking water and wastewater treatment. Even in Billings, approximately mid-point along the length of the river, the water has already been used several times. The river is also important to these communities because of the agricultural activities that are supported via irrigation projects and systems. In turn, and especially in the small towns, the economies of those communities are dependent on agricultural families for their economic well-being. It is important to keep in mind that for many of these communities, their economies are primarily defined in terms of agricultural activities.

Yellowstone River Cumulative Effects Analysis

After extensive flooding in 1996 and 1997, dozens of studies examined the mechanics, biologic communities, and uses of the Yellowstone River. As sets of resources, these studies contributed to the Yellowstone River Cumulative Effects Analysis (CEA), an in-depth, multidisciplinary look at the responses of the river to incremental human activities over the course of time, published in 2015 (YRCDC). Many of the details presented throughout this case study draw from the extensive resources associated with the CEA. As a reader, you may want to access those studies directly, which you can do by visiting the Yellowstone River Clearinghouse (n.d.), maintained by the Montana State Library.

The clearinghouse also hosts an interactive map that makes it convenient for readers to look at various elements of the case study in close detail (Yellowstone River Conservation Districts Council n.d.b.). We encourage you to look at the historic and contemporary images housed there. Before your first visit to the map, it will be helpful if you know to approach your viewing in terms of the terminology of the CEA study designers who examined the river as a series of reaches. Each river reach is characterized and defined by physiographic elements—a definable set of physical attributes that shape the river for a determined distance. When the characteristics of the river change, a new reach is designated. Some reaches are rather short, and others are much longer, with differences in length being determined by changes in attributes, including sediment types, sedimentation, channel sinuosity, and so on. For instance, Reach A16 is defined by much meandering among several channels of the river. In comparison, Reach PC19 is in one main channel, with virtually no side channels or sandbars. In the interactive map, you will be able to zoom in on images that will make it easier to understand the content of this case study. While this case study is complete without the interactive map, we think it will be far more interesting for readers who periodically look at the electronic images.

In Chapter 2, we will examine three key economic activities in the valley: agriculture, tourism, and oil and gas development. We address agriculture as our first area of discussion because farming and ranching are the dominant activities throughout much of the valley. Second, we will examine tourism. There are tourism activities throughout the valley, but for our purposes we will narrow our focus to the tourism generated near the entrance to YNP, specifically in the Livingston and Gardiner areas. Finally, we will turn to oil and gas development. When one considers the economy of the lower reaches of the river—near the towns of Glendive and Sidney—those communities are very dependent on this industry. As we become familiar with three of the most important economic activities in the Yellowstone River Valley, we will frame our sustainability questions as follows: (a) Are current agricultural practices sustainable? (b) Are current tourism practices sustainable? and (c) Are current oil and gas practices sustainable? Importantly, we might also begin to ask: Can we sustain all three industries into the future?

In Chapter 3, we will examine two elements of environmental sustainability in the Yellowstone River Valley. Each of these concerns brings into focus issues regarding the long-term sustainability of our current environmental practices. To begin, we will examine the situation of the Pallid Sturgeon. This prehistoric fish species is heading toward extinction, but efforts are underway to improve its numbers. Second, we will examine the decline of the cottonwood forests by considering evidence that might make us rethink how we manage flooding in our river bottoms. As we become familiar with these two environmental concerns in the Yellowstone River Valley, we will frame our sustainability questions as follows: (a) Will our current practices allow for the long-term sustainability of the Pallid Sturgeon? and (b) Will our current practices allow for the long-term sustainability of the cottonwood forests? Importantly, we will also ask: What practices need immediate adjustments to sustain these elements of the river valley ecosystem?

Chapter 4 examines elements of social sustainability in the Yellowstone River Valley. We will begin by defining a few important terms, including equality, equity, and environmental justice. From that foundation we will examine scenarios involving public rights and access to public resources. Next, we will examine some mishaps in the oil and gas industry and begin to think about our understandings of fairness in these circumstances. Finally, we will briefly consider the relationships between social sustainability and social stability. As questions of social well-being emerge through these examples, we will begin to see how social sustainability is directly tied to economic and environmental sustainability in the Yellowstone River Valley.

Chapter 5 is designed to illustrate sustainability’s complexities. It begins with the topic of water rights and notes that issues arise because many aspects of contemporary water laws, written to suit societal needs of 1872, remain essentially unchanged in principle and execution in contemporary times. It is in this context that we examine the rights of American Indians. Then, we will examine the riparian areas, channel migration processes, and floodplains of the Yellowstone River. We will give attention to the services drawn from healthy riparian areas and to the practices that threaten their health. We note that riparian areas are not fully understood and that they are seldom valued for the full array of benefits they provide humans. Yet, healthy riparian areas are key to the long-term sustainability of the valley. Chapter 5 also highlights the notion of resilience—the ability of environmental and human communities, including businesses, to adapt to stress and change. Readers are encouraged to engage in thoughtful conversations about the complexities associated with trying to improve sustainability and resilience in the valley. We ask: (a) Will current practices concerning water rights allow for sustainability in the Yellowstone River Valley? and (b) Will current practices allow for the long-term health of its riparian areas?

Finally, Chapter 6 shows how detailed attention to sustainability has become a science—sustainability science. In sustainability science, researchers seek to understand complex systems with the intention of intervening to move them toward sustainability. We discuss the central role of communities in sustainability science and how communities of scientists and residents can use resilience to design actions to pursue sustainability.

Inputs From Yellowstone River Valley Residents

In 2006, 2012, and 2018, the authors led investigations into the cultural contours of local interests regarding river issues. They designed an interview protocol that focused on individuals’ knowledge of social, ecological, and physical (fluvial) dynamics based on their experiences with the river. They recruited residents throughout the Yellowstone River Valley and interviewed a total of 453 people. During these interviews, residents were encouraged to explain, in their own words, their concerns and hopes for the Yellowstone River and its resources. Known as the Yellowstone River Cultural Inventory (YRCI), detailed summary reports of those confidential interviews are available to the public at the Yellowstone River Clearinghouse. Several scholarly reports were published that include analyses of residents’ concerns about ruptured pipelines (Emerson, Hall, and Gilbertz 2021), the strengths drawn from agricultural identities in conservation efforts (Horton et al. 2017), how social power and influence factor into defining ecological goals (Hall et al. 2015), how cultural context affects policy development (Hall et al. 2012), the role of local wisdoms in on-site resource management (Gilbertz et al. 2011), and how local leaders balance managing the interests of the public and individuals concerning this shared environmental resource (Horton et al. 2019).

In 2013 and 2014, the authors were also involved in the design and execution of the Yellowstone Basin water planning efforts led by the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC). The water planning efforts involved working directly with the Yellowstone Basin Council to collect and analyze public comments from over 130 valley residents concerning their priorities around water availability, drought readiness, water rights, and state and federal oversight. The team recorded over 100 hours of the council’s deliberations. The council’s product, the basin plan, is available to the public (Yellowstone River Basin 2014).

In addition, several analytical articles were published examining the basin planning activities, including works addressing the mechanisms for successful stakeholder engagement (Hall et al. 2021), the degree to which scientific and technical data informed decision making (Gilbertz et al. 2019), the role of prior appropriations doctrine as an aid and a hinderance to deliberations (Anderson et al. 2018), the policy implications of organizing public inputs at local verses basinwide scales (Ward et al. 2017), the strategic implications of introducing “shared giving” as a forward-looking planning option (Anderson et al. 2016), and the value of gathering qualitative research data during public participation events and deliberations (Hall et al. 2016).

Finally, in 2015 and 2016, confidential interviews were conducted in eastern Montana with more than 30 residents for the purpose of understanding the impacts of oil and gas development on local communities. While those interviews have not been summarized as public reports, they have served as the basis for an analysis of local risk perceptions (McEvoy et al. 2017) and for an examination of eastern Montana as an unlikely example of planetary urbanization (Gilbertz, Anderson, and Adkins 2021).

From the tens of thousands of comments gathered over the last 15 years, some confidential and some public in nature, we have selected a few quotes for each chapter that illustrate how comments from residents of the valley expose concerns related to fundamental sustainability issues. Their comments are presented to maintain confidentiality for all, with indications of where in the valley the person resided, the year the comment was made, and the residents’ primary stakeholder affiliation.

Often, residents’ comments only imply sensitivities to sustainability concerns, but at times the connections are remarkable. Thus, we end Chapter 1 and launch our exploration of sustainability’s central question with this quote from a farmer who was asked to describe his long-term goals:

I have a certain amount of estate that I can hand to my kids. But just think about it, two or three generations beyond, no one’s going to scarcely remember me. But, if they can go down to the river and stand on that bank, and I did something positive that helped set the stage to keep that river intact, what a legacy. That’s how we have got to view it. That way, or it will go away … [if] people just keep gnawing at the fringes and the edges of it … I mean the river is such a grand place. Yeah, we haven’t reached that danger point. I hope that we can somehow do all the right things, so that in four or five or ten generations they’re still going to call it the Crown-Jewel-River of the country. Wouldn’t that be something? (Farmer near Miles City 2006)

1. In what ways have local and regional industries already changed their practices to improve the long-term profitability and economic well-being of our communities?

2. In what ways have advocacy groups influenced society to adopt practices that will improve the environmental sustainability of our communities?

3. In what ways have public calls for action moved society to adopt practices that will improve social sustainability of communities?

4. How do comments made by the farmer near Miles City illustrate sensitivity to sustainability’s central question?

Easy Access Resources

Interactive Map Yellowstone River Cumulative Effects Analysis and the Yellowstone River: http://montana.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=3fc5b219f4494ebab2477e93a5bbecca

Population Statistics, United States: https://suburbanstats.org/

Three Pillars of Corporate Sustainability, explained by Andrew Beattie: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/100515/three-pillars-corporate-sustainability.asp

USGS Publications Warehouse: https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/

Yellowstone River Data Clearinghouse: http://geoinfo.msl.mt.gov/data/yellowstone_river/about