Manage Your Knowledge

Now it’s time to work with your ideas, insights, raw information, and knowledge and transform the whole stewed mess into something transcendent.

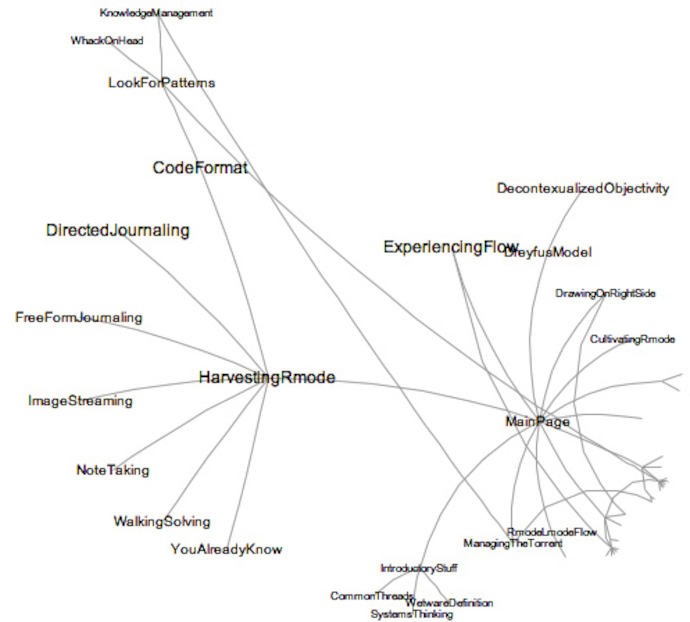

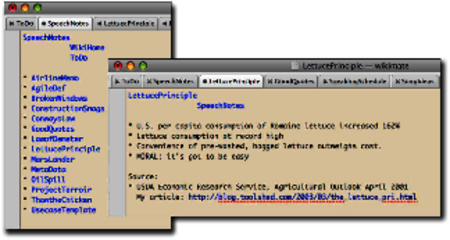

But for once, what you need doesn’t fit in your brain. You need to augment your processing power (see Figure 22, A Network of WikiWords).

Figure 22. A Network of WikiWords

What are all these topics, and why are they all WrittenFunny? Allow me to explain…

Developing Your Exocortex

As I said in Capture Insight 24x7, you need to be prepared to capture information anywhere, anytime. But once you’ve captured it, you can’t just let it sit there—that won’t do you any good. You need to work with the material: organize it, develop it, coalesce disparate material, and refine and split general ideas into more specific ones.

You need a place to put your thoughts where you can work with them effectively. Thanks to modern technology, I recommend you use some sort of hyperlinked information space that allows easy self-organization and refactoring. But before we delve into the details, let me explain why this type of storage is so important.

This is not some mere clerical activity. According to the research into distributed cognition, the tools you use for mental support outside your brain become part of your operating mind. As marvelous as the brain is, we can turbo-charge it by providing some key external support.

External support is part of your mind.

Thomas Jefferson owned somewhere in the neighborhood of 10,000 books in his lifetime.[143] Jefferson was an avid reader, and these books ranged on topics from political philosophy to music to agriculture to wine making. And each book became a little part of his consciousness—probably not the whole thing; most of us don’t have encyclopedic memories. It’s enough to know you’ve read about it once and remember where to go find the details.

Albert Einstein knew this well. Supposedly he was once asked how many feet there were in a mile and replied that he wouldn’t fill his brain with things that could easily be looked up. That’s what reference books are for; that’s an efficient use of resources.

Your own book collection, your notes, and even your favorite IDE and programming language all form part of your exocortex, which is any mental memory or processing component that resides outside your physical brain. As programmers and knowledge workers, we probably rely on the computer to form more of our exocortex than the general population does. But of course not all computer-based tools are created equal.

For marinating, categorizing, and developing thoughts, I find one of the most effective tools to be a personal wiki. In fact, as we’ll see, by organizing your great ideas this way, you’ll get more great ideas.

Use a Wiki

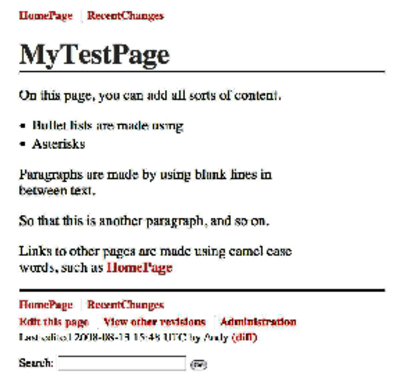

A traditional wiki (short for Wiki-Wiki-Web) is a style of website that allows anyone to edit each web page using nothing more than a regular web browser. At the bottom of every page is a link labeled Edit This Page, as shown here:

Figure 23. Displaying a wiki page

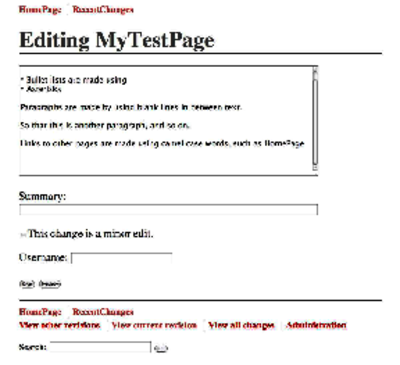

Clicking that link presents the contents of that page in an HTML text-editing widget. You can then edit the page and click the Save button, and your changes are now part of that web page. The markup is usually simpler than raw HTML; for instance, you can use * characters to create a bullet list, underscores for italics, and that sort of thing, as shown in the following figure. Most important, however, is the ability to link to other pages.

Figure 24. Editing a wiki page

You create a new page by first creating a link to it, using a WikiWord. A WikiWord is a word formed by jamming together two or more words with initial capital letters and no spaces. Once you place a WikiWord on a page, it will automatically become hyperlinked to the wiki page with that name. If one doesn’t yet exist, then the first time you click it, you’ll be given a blank page and the opportunity to fill it in. This makes it very easy and natural to create new pages.

But traditional wikis are web-based and have this innate separation between edit and display mode. If you need your wiki to be a web-based app for whatever reason, then that’s a fine way to go. But for our purposes here, you might be better off with a slight variation on this technology.

Use a wiki as a text-based mind map.

You can use a wiki implemented in your favorite text editor—a wiki-editing mode. This gives you WikiWord hyperlinks and syntax coloring or highlights within your editor environment. I’ve used this feature in the vi, XEmacs, and TextMate editors to good effect. A wiki feels like a text-based mind map (and speaking of which, you might well use a mind map to help clarify and augment one section of the wiki).

One of my most successful wiki experiments was setting up a PDA as a synchronized wiki to my desktop. I used a Sharp Zaurus, a small, pocket-sized PDA with a thumb keyboard that runs Linux. I installed the vi editor and wrote some macros to give it hyperlink traversal and syntax highlighting for wiki links and so on. Then, I could synchronize the set of flat files that comprise the wiki using a version control system designed for source code (CVS, in this case).

The result is a portable wiki-in-my-pocket that is versioned and synchronized with my desktop and my laptop. Wherever I am, I have my mental wiki space with me. I can create and augment notes, work on articles or books (including this one), and so on.

While writing this book, I began to move away from the Zaurus and began using an iPod Touch, where I’ve got a custom Ruby-based web server that offers a more traditional, web-based wiki using this same synchronized wiki database.

You might want to investigate the same sort of thing on your laptop or PDA to free you from having to be at your desk to work your wiki. There are numerous wiki implementations to choose from. For an up-to-date list, take a look at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Personal_Wiki.

| Recipe 41 | Use a wiki to manage information and knowledge. |

The real beauty of this approach is that once you have a place to put a specific bit of information, you’ll notice that new, relevant bits of data suddenly start to show up out of nowhere. It’s a similar phenomenon to sense tuning. For example, if I told you to start looking for the color red at a party, you’d suddenly start to see red everywhere. The same thing happens with a new model car. You’re attuned to it, so where you may not have paid attention previously, suddenly the thing you’re looking for will jump out at you.

With a wiki, you may have a random idea and write it down on your home page because you don’t know what else to do with it. Some time later, you have a second idea that goes with it, and now you can move the two thoughts off together on their own new page. Now suddenly more things will come up that belong on that page—you have a place to put it, and your mind will happily oblige.

Use sense tuning to collect more thoughts.

Once you have a place to put some type of thought, you’ll get more thoughts of that type. Whether it’s a wiki or a paper journal, note cards, or shoe boxes, having a place for ideas in a specific topic area or project is a major benefit of an exocortical system.

For example, take a look at the screenshot in the following figure. This shows my personal wiki format; the title of the page appears at the top of each page, then some convenient links to other wiki pages (such as ToDo) appear. WikiWords, which link to pages of the same name, are highlighted in blue—the same as regular web URLs.

Figure 25. Wiki notes

I first came across a neat fact about lettuce consumption and made a page called LettucePrinciple. I heard a great joke/urban legend with the punch line “Thaw the chicken” that I thought might be useful, so I noted it in ThawTheChicken. Then NASA lost a $125M satellite because of a programming error with mismatched units, so I jotted the facts down in MarsLander.

Now that I had a couple of these kinds of thoughts floating around, I made a simple list called SpeechNotes, with the idea that I’d accumulate stuff for presentations from here. I put in ConwaysLaw, the LawofDemeter, OilSpill, and other stuff I’d used already and added a couple new ideas, such as ProjectTerroir. Now LettucePrinciple had a home, a place with similar topics, so I added it to that list. I used it as part of a presentation at a RubyConf on technology adaptation and then a blog posting.[144]

The list grew to several hundred items, which was bad. I started some wiki gardening and cleaned things up. I made different lists for blog posts, upcoming presentations, basic stories and research, and so on. Notes for some particular article might reference a half dozen of these pages; a book outline might pull in two dozen. But wikis are useful for more than just this kind of organization.

Transcribing your notes from their original form into the wiki (or cleaning them up in the same wiki) helps get your brain around the material. Just as transcribing notes taken in a meeting or in a class, this provides a second in-depth exposure to the material and more neural reinforcement.

And the more you work with it, the more you may start to see relationships and patterns in the material that you hadn’t noticed before. And again, you can go off and mind map some of the more interesting bits to gain insight and bring that back to the wiki.

You’ll be able to deliberately look for patterns.

But you want to keep your focus on what you’re working on and not get distracted. In the next section, we’ll see why.