Harvest R-mode Cues

Despite years of being ignored, your R-mode remains hard at work, toiling away in the background to match up disparate facts, make far-flung associations, and retrieve long-lost bits of important data from the morass of otherwise uninteresting memories.

In fact, it’s entirely possible that your R-mode already has exactly the answer to the most important problem that you’re working on right now.

But how can you get at it? We’ll spend the rest of this chapter looking at techniques to help invite, coax, ferment, and jiggle great ideas out of your head.

You Already Know

You may already have that great idea or know the solution to that impossibly vexing problem.

Your brain stores every input it receives. However, even though stored, it does not necessarily index the memory (or if you prefer a more die-hard computer analogy, “store a pointer to it”).

Every input gets stored.

Just as you can arrive at work with no memory of how you got there (as we saw earlier), the same thing can happen while you’re sitting in a lecture hall, sitting in a training seminar, or reading a book. Even this one.

But, all is not lost. It turns out that when you are trying to solve a hard problem, all of your memories are scanned—even the ones you cannot consciously recall. It’s not the most efficient thing (I’m envisioning something like a SQL full-table scan on a large table with very long rows), but it does work.

Have you ever heard an old song on the radio and then several days later you suddenly remembered the title or artist? Your R-mode was still working on the problem, asynchronously in the background, until it finally found the memory.

But many times the answer isn’t so easily divulged: the R-mode, after all, cannot process language. It can retrieve chunks of it from memory, but it can’t do anything with it. This leads to some rather odd scenarios.

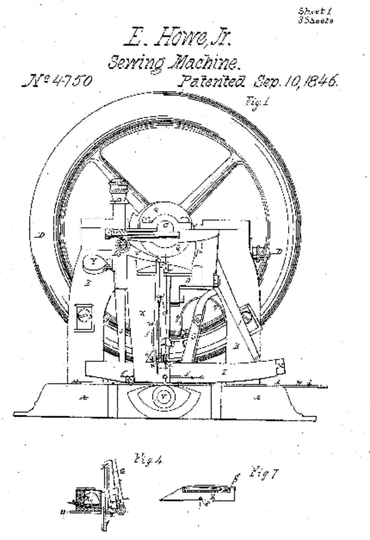

The Strange Case of Elias Howe

In 1845, one Elias Howe was struggling to invent a practical lockstitch sewing machine. It wasn’t going very well for him. One night, after a long, hard, unproductive day, he had a terrifying nightmare—the wake-up-screaming, projectile-sweating kind of nightmare.

In the nightmare, he was in Africa, abducted by hungry cannibals. About to be made into stew, he was quite literally in a lot of hot water. As he tried to escape, the headhunters kept poking at him with their funny-looking spears.

As he’s describing the nightmare the next morning, his attention focuses on the “funny-looking spears.” What made them odd was that they had holes in the end, in the barbed tip of the spear; it was almost like holes in a handheld sewing needle but up at the tip. Hey…

Figure 12. Elias Howe’s patent

Elias went on to receive the first American-issued patent for an automatic sewing machine, based on his hard-won inspiration that the hole for the needle needed to be opposite the normal, handheld orientation.

It would seem that Elias already knew the answer to this difficult technical problem—at least, his R-mode had retrieved an answer. But since the R-mode is nonverbal, how can it be presented to the L-mode for processing?

The R-mode has to throw it over the fence visually, in this case wrapped up in the disturbing—and very memorable—imagery of an outlandish dream.

And as it turns out, you have many excellent skills and ideas that are simply not verbalizable. As noted earlier (in Chapter 3, This Is Your Brain), you can recognize thousands of faces, but try to describe even one face—that of a spouse, parent, or child—to any degree of accuracy. You don’t have the words to describe it. That’s because facial recognition (and indeed, most pattern-based recognition) is an R-mode activity.

Many ideas are not verbalizable.

You might also notice that you can’t read text that appears in dreams, such as road signs or headlines. Most people can’t.

Let us now take a quick look at two different ways of harvesting some of this R-mode recognition: image streaming and free-form journaling.

Harvesting with Image Streaming

In the case of Elias Howe, the answer he was seeking was being presented in the form of a dream. You might experience the same thing once you start paying more attention to the contents of your dreams. Not all dreams “mean something.” Sometimes in a dream “a cigar is just a cigar,” as Sigmund Freud reportedly said. But there are many times when your R-mode is trying to tell you something, something that you want to know.

Image streaming is a technique designed to help harvest R-mode imagery.[62] The basic idea is to deliberately observe mental imagery: pay close attention to it, and work it around in your mind a bit.

First, pose a problem to yourself, or ask yourself a question. Then close your eyes, and maybe put your feet up on the desk (this is perfect for doing at work) for about ten minutes or so.

For each image that crosses your mind, do the following:

-

Look at the image, and try to see all the details you can.

-

Describe it out loud (really use your voice; it makes a difference). Now you’re sitting with feet up on the desk and talking to yourself.

-

Imagine the image using all five senses (or as many as practical).

-

Use present tense, even if the image was fleeting.

By explicitly paying attention to the fleeting image, you’re engaging more pathways and strengthening connections to it. As you try to interpret the image, you’re broadening the search parameters to the R-mode, which may help coalesce related information. At any rate, by paying close attention to those “random” images that flit across your consciousness, you may begin to discover some fresh insights.

It’s not magic, and it may or may not work for you, but it does seem to be a reasonable way of checking in with the rest of your brain.

A fair percentage of the population will not see any images in this fashion. If that’s the case, you might try to artificially induce a random image by gently rubbing your eyes or briefly staring at a light source (this creates what is called a phosphene, the sensation of seeing light from some nonvisual source).

The source of the image is not that important; how you try to interpret it is. We’ll talk more about this phenomenon in just a bit.

Harvesting with Free-Form Journaling

Another simple way of harvesting your R-mode’s preconscious treasures is to write.

Blogging has enjoyed tremendous popularity in recent years, and probably rightfully so. In previous eras, people wrote letters—sometimes a great many letters. We saved the best ones from famous people such as Voltaire, Ben Franklin, Thoreau, and other notables.

Letter writing is a great habit. Sometimes the material is relatively dull—what the weather was doing, how the prices at the market were up, how the scullery maid ran off with the stable boy, and so on. But in the detailed minutiae of everyday life were occasional philosophical gems. This sort of free-form journaling has a long pedigree, and those skillful thinkers from days gone by were eventually well regarded as “men of letters” for penning these missives.

Today, blogs are taking on this role. There’s a lot of “what I had for breakfast” and the occasional virulent rant indicative of declining mental health, but there are also penetrating insights and germs of ideas that will change the world. Some already have.

But there are many ways to write your thoughts down, and some are more effective for our purposes than others. One of the best is a technique known as morning pages.

The Morning Pages Technique

This is a technique that I first heard about in the context of a writer’s workshop (also described in The Artist’s Way [Cam02]); it’s a common technique for authors. But I was surprised to also come across it in a popular MBA program and in other senior executive--level courses and workshops.

Here are the rules:

-

Write your morning pages first thing in the morning—before your coffee, before the traffic report, before talking to Mr. Showerhead, before packing the kids off to school or letting the dog out.

-

Write at least three pages, long hand. No typing, no computer.

-

Do not censor what you write. Whether it’s brilliant or banal, just let it out.

-

Do not skip a day.

It’s OK if you don’t know what to write. One executive taking this program loudly proclaimed that this exercise was a complete waste of time. He defiantly wrote three pages of “I don’t know what to write. Blah blah blah.” And that’s fine.

Because after a while, he noticed other stuff started appearing in his morning pages. Marketing plans. Product directions. Solutions. Germs of innovative ideas. He overcame his initial resistance to the idea and found it to be a very effective technique for harvesting thoughts.

Why does this work? I think it’s because you’re getting an unguarded brain dump. The first thing in the morning, you’re not really as awake as you think. Your unconscious still has a prominent role to play. You haven’t yet raised all the defenses and adapted to the limited world of reality. You have a pretty good line direct to your R-mode, at least for a little while.

Thomas Edison had an interesting twist on this idea. He’d take a nap with a cup full of ball bearings in his hand. He knew that just as he started to drift off into sleep, his subconscious mind would take up the challenge of his problem and provide a solution. As he fell into a deep sleep, he’d drop the ball bearings, and the clatter would wake him up. He’d then write down whatever was on his mind.[63]

The “Just Write” Technique

And then there’s blogging itself. Any chance to write is a good exercise. What do you really think about this topic? What do you actually know about it—not just what you think, but what can you defend? Writing for a public audience is a great way to clarify your own thoughts and beliefs.

But where to start? Unless you’re burning with passion for some particular topic, it can be hard to sit down and just write about something. You might want to try using Jerry Weinberg’s Fieldstone method, described in Weinberg on Writing: The Fieldstone Method [Wei06].[64]

This method takes its name from building fieldstone walls: you don’t plan ahead to gather these particular stones for that wall. You just walk around and pick up a few good-looking stones for the future and make a pile. Then when you get around to building the wall, you look into the stone pile and find a nice match for the section you’re working on at the moment.

Make a habit of gathering mental fieldstones. Once you have some piled up, the process of building walls becomes easy.

It’s a good habit to get into.

Harvesting by Walking

You can harvest R-mode cues just by walking, if you do it right. Do you know the difference between a labyrinth and a maze?

According to the Labyrinth Society,[65] a maze may have multiple entrances and exits, and it offers you choices along the way. Walls prevent you from seeing the way out; it’s a puzzle.

A labyrinth is not a puzzle; it’s a tool for meditation. Labyrinths offer a single path—there are no decisions to be made. You walk the path to sort of give the L-mode something to do and free up the R-mode.

It’s the same idea as taking a long walk in the woods or a long drive on a straight, lonely stretch of highway, just in a smaller more convenient space.

Labyrinths go back thousands of years; you’ll find them today installed in churches, hospitals, cancer treatment centers and hospices, and other places of healing and reflection.

Have you ever noticed that great ideas or insights may come to you at the oddest times? Perhaps while taking a shower, mowing the yard, doing the dishes, or doing some other menial task.

That happens because the L-mode sort of gets bored with the routine, mundane task and tunes out—leaving the R-mode free to present its findings. But you don’t have to start washing a lot of dishes or compulsively mowing your yard in order to take advantage of this effect.

In fact, it’s as easy as a walk on the beach.

Henri Poincaré, the famous mathematician, used a variation of this idea as a problem-solving technique.[66] Faced with a difficult, complicated problem, he would pour everything he knew about the subject onto paper (I’ll suggest something similar in a later section; see Visualize Insight with Mind Maps). Looking at the problems that this step revealed, Poincaré would then answer the easy ones right away.

Of the remaining “hard problems,” he would choose the easiest one of those as a subproblem. Then he would leave his office and go for a walk, thinking only about that particular subproblem. As soon as an insight presented itself, he would break off in the middle of the walk and return to write the answer down.

Repeat this process until everything is solved. Poincaré described the sensation: “Ideas rose in crowds; I felt them collide until pairs interlocked, so to speak, making a stable combination.”

If you don’t have a labyrinth at hand, just go for a walk around the parking lot or down the hall. However, try to avoid just walking around the office because that might offer too many distractions: a co-worker’s conversation, an impromptu meeting with the boss or client, or an assessment of the latest sports scores or political intrigue at the water cooler all will distract you from the problem in a negative way.

Now, I may have just misled you in the past several paragraphs. When you go for your “thinking walk,” don’t actually do any thinking. It’s important to draw a vital distinction between R-mode and L-mode processing. L-mode is deliberate: when you focus, when you concentrate, that’s L-mode at work. R-mode is different. It can’t be commanded, only invited.

R-mode can be invited, not commanded.

You have to sort of defocus a bit. In the Laws of Form [Spe72], mathematician George Spencer Brown refers to this not as thinking but as simply “bearing in mind what it is that one needs to know.”

As soon as you focus on a goal, L-mode processes will dominate, and that’s not what you want here. Instead, you want to cultivate a style of non-goal-directed thinking. As Poincaré did, dump everything out onto paper (or into an editor buffer, if you must), and then leave it be. Don’t rehash it or go over it in your mind. Bear it in mind, as Brown suggests, but don’t focus on it. Hold it ever so lightly in your thoughts. Let the stew of facts and problems marinate (we’ll talk more about this in Defocus to Focus).

| Recipe 16 | Step away from the keyboard to solve hard problems. |

And then when you least expect it, you may find that the answer will emerge by itself.

|

Now put the book down. Go for a walk. I’ll wait. |