The future and the past: models are changing

This chapter

This chapter will introduce you to the future through the vehicle of the past. In doing this we can begin to get a feeling of how we have seen the future and how often this is without a framework or understanding. We are now using tools which will help us establish horizons to the future. In looking from the past we can see that consortia have played a much stronger role and will do so into the future. We will also look at what the business model means to libraries and especially if we are expecting changes to the library's operations through this scenario process.

The mirror as a powerful tool

The mirror is a personal tool used to help us understand the reality of what we are rather than the perception we may think of ourselves. In this way, it tells us of the real world. It can be cruel; it can be kind depending on our own understanding of what or who we are.

The rear vision mirror is also a powerful tool used, as it is mostly, in a motor vehicle to reflect where we have been. To extend the analogy, what we see in the rear vision mirror is an image of a time past. It may be of only the very recent past but it is of the time past … where we have been already. It is far more difficult but it is really interesting to go back to where the rear vision mirror sees that we have been and to look forward. If we were able to go back to that past point and look forward we would be able to see the future. Many a science fiction writer has sought to create this capability, enabling us to visit different time periods and to see both into the past and into the future. So the rear vision mirror is a very useful instrument for us to begin to understand our past, our present and through this to our future.

As we discussed in Chapter 1, history is not linear but our progress from Point A to Point B is littered with decision points and obstacles which cause us to go in different directions. It is always difficult to see a situation in the future. But we can look at it through the rear vision mirror. If we were to look back in our lives, we can remember how we felt and thought about certain events in our past lives. So it is for events in our professional lives. We can draw into our minds what we were thinking at the time as we remember when we first became aware of a computerised version of the card catalogue; when we became aware of the first personal computer being available in a library; when we first became aware that the Internet would be able to present digital content for the library; when we became aware that library content could be delivered digitally to a library's clientele no matter where they were located. By casting our minds back to that moment and remembering, from that perspective we can begin to understand how we saw the future at that time. We can understand our often ‘inadequate’ view of the future from one of those present moments. Looking back will also enable us to recollect the various choices which had been made to get us to the present moment. Yet remembering how we thought in that past time, the path to the future might have been considered linear. As we reflect on that past moment, we begin to see all of the characteristics in that situation which may have led to the future developments. When journal articles commenced being distributed on compact disc (CD), it was soon evident that this was a very welcome development. However, the volume of content was soon overwhelming the delivery vehicle … the humble but relatively new technology the CD. The characteristics to recognise at that point were twofold: one, that the delivery of content via digital means was going to be the future path; secondly, there would need to be new technological devices to deliver that content. In planning terms it is not necessary for us to identify what the technology might be but to recognise that the direction was becoming clear. Plan for digital delivery. Plan for mass delivery of content. By extension, plan for the gradual transfer of much content into digital form.

Figure 3.1 Rear vision mirror Source: This image is used with the kind permission of David Hobbs. http://hobbsie.smugmug.com.

Library models in transition

A library is a library is a library. At least this is the way it used to be. Libraries would collect and service, relating to their native client group while retaining their independence in all respects. In the past 40 years that natural order of things has begun to change with the emergence of umbrella groups to assist the libraries to achieve greater orders of efficiency and effectiveness. Most often, as the next section indicates, this was to achieve greater technological benefit. As the power of computers especially has increased they have also become smaller and more local, not normally requiring great central computer grunt. There are a few notable exceptions. An umbrella group became a consortium and now we have many consortia across the globe. But what is and will be the intersection mark between the two types of organisation?

Consortia in our corporate lives

An integral aspect of the life of the modern library is its relationship to one or more library consortia. Each library will belong to at least one consortium while many libraries will belong to many consortia. There has been an abundance of these organisations to assist libraries achieve different objectives or services. It is interesting to use the ‘rear vision mirror’ tool to see where consortia have come from and perhaps begin to understand their future role and that of the library’s relationship to them.

The major consortia which came into existence in the 1960s did so, primarily, to operate union catalogues. Organisations such as BLCMP, OCLC and CAVAL established union catalogue operations to reduce member cataloguing operational costs by maintaining union catalogues and providing copy cataloguing facilities.

It is one thing to say that these union catalogues were established and operated. It is also worth reflecting on the huge changes and impacts which they had on library operations and staffs. Cataloguing departments in each organisation were previously independent from similar units in other organisations. With the creation and spread of the union catalogues, cataloguing departments were now increasingly connected and their practices became more and more uniform. The rear vision mirror tool may have foreseen the gradual but certain demise of the numbers of professional staff members in cataloguing departments.

In a similar but certain way, it is becoming increasingly obvious that cataloguing departments will merge into regional entities. If this is the case, the role of the library consortia will have again significantly altered the future of library members and their staffs. This is an interesting example of where a technological change has fundamentally changed a significant part of the library profession and certainly the way in which practice occurs in libraries. It has been a gradual but fundamental change; one that is not reversible. The practice of cataloguing, its standards and rules might have changed for ever but the utter importance of good clean data has not changed. This legacy will continue through the practice of the profession.

Various consortia spawned by OCLC, including SOLINET, PALINET, AMIGOS, NELINET and so on came into existence to support and market the central services of OCLC in geographic areas. Gradually each of these organisations took on other roles for their members. They also established themselves with their own governance. Looking backwards, the power of the computer to manage large data operations such as catalogue records was the prime driver for the existence of these organisations. In a sense, a technology enabled libraries to form these new organisations for a specific purpose while these organisations have changed their founding members and will do so again. Consortia have served their purpose well over the years but are in the process now of re-inventing themselves.

In the library landscape we now find other consortium organisations which are devoted to different purposes other than cataloguing. These might include Centre for Research Libraries (CRL), which collects research materials for their members, CAVAL, which operates a shared repository for research materials of low usage, and a growing band of similar organisations. The term consortium has now been extended to include organisations banding together for the purposes of negotiating deals for access to electronic resources. There is even an organisation of library consortia. This is International Consortium of Library Consortia (ICOLC). So the vehicle now called a consortium has found a number of purposes for librarians to achieve collective purposes.

Changing roles of and pressures on consortia

So each consortium has developed in different ways to serve its members best. These developments include staff development programmes, consultancies, low-use book and serial collaborative storage and multi-language cataloguing services. The developments have been evolutionary. Especially notable have been the emergence of joint negotiation facilities for digital products for member libraries. Excelling and leading in this area has been SOLINET,1based in Atlanta, Georgia. It has well over 2,500 library members and has negotiated bulk deal discounts for members seeking to subscribe to various digital services. SOLINET also negotiated a deal for all the libraries in the United States wishing to subscribe to Lexis-Nexis digital legal services. There are many consortia organisations which now exist and operate strongly in the management of digital subscription deals. Over 150 of these organisations worldwide belong to the self-managed, informal International Coalition of Library Consortia. This ‘consortium of consortia’ may conduct meetings dedicated to keeping participating consortia informed about new electronic information resources, and pricing practices of electronic providers and vendors.2 So the main driver for many consortia today is to reduce the impact of their member library budgets and to discernibly add value to their member organisations. Still, the members are the dominant organisations with the consortium having its existence only as a result of the members. In a sense, they do not have lives of their own. Indeed, in the current financial crisis worldwide many smaller consortia will cease to exist or will merge with larger organisations. SOLINET, PALINET, NELINET and now BCR decided to merge. The effective date for the new organisation, Lyrasis, was 1 April 2009. They are committed to continuing their businesses as usual as the organisations are merged.3 Each consortium organisation will reflect and cogitate on its own future. The path of SOLINET to a new future was based on its own scenario planning. The possible scenarios which were developed are included in the case studies in Chapter 9 of this book.

Clearly many of the consortia spawned by OCLC well over 40 years ago are suffering severe financial pressures as the spawning organisation itself engages in a fundamental rethink about its relationships and role in the library industry. OCLC has been engaging in ‘disintermediation’, having decided to sell its products and services directly to the end customer rather than through the consortia such as SOLINET, PALINET, AMIGOS and NELINET. The disintermediation is important to understand in the operating environment. From the OCLC point of view, the consortia which it spawned some years previously were no longer necessary as part of their service delivery and marketing processes. It is therefore a time to reflect on how many consortia libraries need and for what purpose. In many ways this reflects not only financial pressures for the previous parent and siblings but the changed status of OCLC with an annual turnover greater than US$50 million. OCLC, of course, has many members but its revenue streams are now not dependent on member fees. Thus the relationship to libraries is, in many ways, reversed from that of other consortia. Having said this, it is clear that membership fees have been reducing, making the fees a bond of commitment rather than a reliable income.

The future of the consortium as an organisational vehicle is strong with possibilities. It has as many futures as librarians want it to have. Kate Nevins, as the Lyrasis Chief Executive Officer, cites the benefits of consortia as being: information access and management; and people and institutional effectiveness.4 Lyrasis now has members across 33 states in the United States and is in a strong position to shape the future landscape of library–consortia relationships. In particular, she talks about the ability of consortia to ‘leverage scale and relationships with members and to combine wealth of individual relationships and partnerships’.5

With these developments the nature of the relationships between libraries, consortia and vendors is sharply changing. Perhaps from the perspective of the rear vision mirror we will see this time as being pivotal to how that partnership works. The traditional relationship between libraries and vendors is now extended to include consortia as real players. How this tripartite partnership works out will depend on the inventiveness and creativity of all three players. It will be testing in that two of the players are not-for-profits while the third is for-profit. The business model will be quite different and will evolve over the next few years.

What are we doing, or what is our business model?

We have talked in this chapter about the tool of the rear vision mirror. We have applied this tool to see what has happened and is happening to the Consortium as an organisation and its relationship with the ‘library’. Now it is timely to understand what libraries have been doing and what they are going to do. This again can be done by using the rear vision mirror tool and then by using the disruptive technology tool (Chapter 2) to understand what could be happening and changing into the future. The business model of any organisation can be severely affected by ‘disruptive technologies’. Business models are important in themselves while in our information industry they describe how each of the players in the industry add value and create a role for themselves. Business models are normally defined in terms of ‘for-profit’ companies. They are, however, equally pertinent to libraries except the currency is different. A company talks of revenue generated whereas the library generates value, information and service.

A business model is a framework for creating economic, social, and/or other forms of value. The term business model is thus used for a broad range of informal and formal descriptions to represent core aspects of a business, including purpose, offerings, strategies, infrastructure, organizational structures, trading practices, and operational processes and policies. In the most basic sense, a business model is the way of doing business. It is the means by which a company can sustain itself – that is, generate revenue. The business model spells out how a company makes money by specifying where it is positioned in the value chain.6

The core business for a library, as we look through the rear vision mirror tool, has been to acquire, catalogue, store and make available published materials. This was the traditional business model for the library. Prior to the digitisation of content, the library provided the archival role by collecting, binding and storing journal and book content. The publishers saw clearly that their business model was to collect content, to publish it, and distribute it to customers – both library and individuals – in print form.

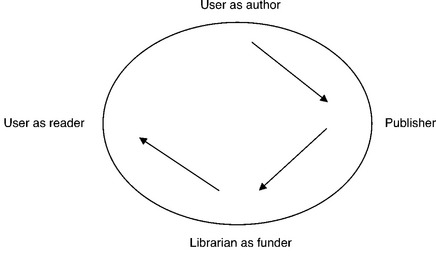

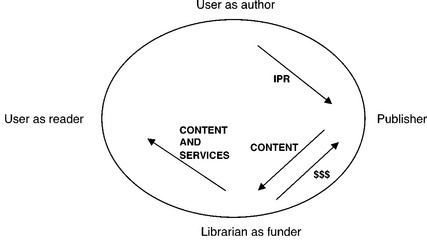

In the first model the Publisher receives the IPR from the Author and the revenue stream from the librarian. The library role in this business model is to fund the publishing enterprise and to deliver the published content to the Reader.

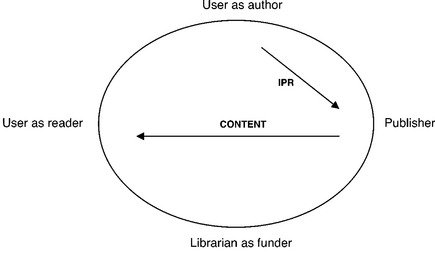

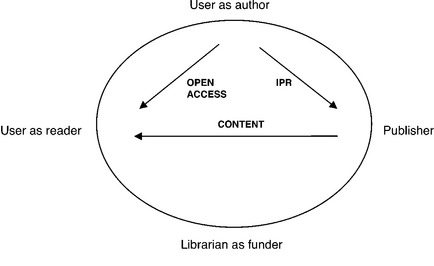

Now the roles have changed and with that the business models. Publishers have new business models for their operations. Publishers still have the need to generate revenue but they have different ways, or business models, for achieving that revenue. One business model is to achieve revenue by selling subscriptions to their traditional client base, the libraries. Another business model will see publishers on-selling content (which they currently own for the lifetime of the author plus seventy years) to other avenues of distribution.

A further business model will be publishers selling content or generating revenue by marketing their services and content directly to the end-user, bypassing the library. In other words, the publishers have the same traditional business model (delivering a mixture of print and digital content) but now have new business models by on-selling content, and by bypassing the library and marketing directly to the individual. In addition, they have greatly strengthened their position by securing ownership of the content through the development and enactment of copyright laws. They are still partners in the delivery of content from the author to the user but they have more options for the delivery of content and, of course, how they generate income or revenue. The diagrams show the traditional business model and also the new business models. There are other business models which are being contemplated which again do not involve the library at all.

The library, on the other hand, has a much more limited scope for its business model. It no longer collects, binds and stores journal literature. The business model for the library has been to assist or fund the publishing process (by purchasing journal and book content) and to make it available to library users. There is nothing inherently wrong with this model. The difficulty is that many of the library’s users who access the digital content online do not even realise that the library has organised and funded that content to be available to them.

The Chinese use the word Wei Jei to describe crisis. As we have seen, however, the word has two aspects to it, Wei meaning danger and Jei meaning opportunity. The danger for libraries in having one depleted or exhausted business model is that they can be bypassed or be considered irrelevant. The opportunity is to create new business models by looking at new futures. In Chapter 2 there was discussion about disruptive technologies. As far as libraries are concerned the mere shift to digital delivery has been a huge disruptive technology. Digital delivery has fundamentally and inexorably changed the library’s business model. Digital content or digital delivery has effectively destroyed the traditional business model. The implications of this are seen in the change in the purpose of the library building from storage to learning. The amount of space required previously for storage has now effectively halved while the user spaces have doubled at least. So what is the basic business model for the library?

Future business models

The ways in which libraries will organise themselves in the future will of course be varied. As discussed already in this chapter, the role of consortia will be incorporated into these library business relationships. Libraries will move more and more to use the services of consortia to negotiate and deliver services which they can achieve best by acting together. In many senses, this is not the rise and rise of consortia but a redefining of the roles and areas of expertise of libraries. This situation has come about because of the disruptive technologies affecting publishing and social connecting environments which were explored in Chapter 1. Libraries in the future will be an extension of consortia and consortia an extension of libraries. But they will have different roles and responsibilities.

What will be different will be the management behaviours which will be required in these altered environments. Staff who are used to hierarchical reporting relationships within a single library will find a very different environment in a wider consortia governing relationship. It will require new managerial and personal skills to achieve consensus and to execute forward actions. This is an important factor as the library staff will only be able to achieve their collective goals in this way.

1.SOLINET initially merged with PALINET to form LYRASIS. Subsequent merges included NELINET and BCR into this new enlarged consortium.

2.Available at: www.library.yale.edu/consortia (accessed on 8 March 2009).

3.Available at: www.mergerupdate.org (as consulted on 8 March 2009).

4.Nevins, K. (2010). ‘Lyrasis: Great Expectations: Library collaboration in challenging times’. Academic Librarian 2. Available at: www.lib.polyu.edu.hk/ALSR2010/programme/presentation/Theme4_Nevins_Presentation.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2010).

5.Ibid.

6.Wikipedia as consulted on 14 March 2009.