The complexities of our informational environment

This chapter

This chapter will examine the concept of the environment as a space in which each of our libraries exists. It will also enable the reader to see the environment for what it is while also analysing, and then beginning to understand, the impacts of the environment. There are various tools which will assist us in these examinations.

By examining the environment we will then have the basis by which to understand, in a subsequent chapter, the business models operating in the publishing and library industries.

What is the environment?

Geologists and sociologists understand our physical and social environments. They understand the contours, the seismic shifts, the changes in attitudes, the movement of populations and social classes. The development of their disciplines involves gathering information from a variety of information sources and integrating them to provide new information. These two disciplines have much in common with the library and information profession.

The geologist and the sociologist have differences, however, in how they can garner facts from their environments. The geologist can rely on observations and investigations about the earth and geological movements. The sociologist knows that there are constant changes in the social order. Attitudes change and there are so many factors which influence the shape of society. Societal changes can be measured and tracked with quantitative and qualitative measures.

Libraries and their environments

The environment in which our libraries operate varies from sector to sector. The environment in which a special library operates is different to that for a public library or an academic library. They differ because of the funding, administrative and political influences. They differ because of the salary scales on offer to their staffs and also, at a more fundamental level, because of their missions and the populations which they intend to serve. These environments need to be understood and to be gauged as to what they are telling us about the possible futures for their libraries. We will talk more about how to deal with these environments later in this chapter.

The wider environments are often more difficult to see and understand but are nonetheless critical to establishing an understanding of what is possible, what is probable and why we need to change our thinking. But there are seismic shifts occurring in each of these environments and it is important to be aware of them and to appreciate, at least broadly, what they mean. The geologist would be concerned that the moving tectonic plates might upset the very foundations of the cities above them. These are the insights which will more strongly drive the scenarios which are developed in later chapters.

Anything’s possible if you’ve got enough nerve. (J.K. Rowling1)

Disruptive technologies

It is worthwhile now talking about ‘disruptive technologies’. This is a business theory popularised by Clayton M. Christensen to describe how a new technology can affect existing technologies, particularly if it is unexpected. In his 1997 best-selling book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Christensen separates new technology into two categories: sustaining and disruptive. Sustaining technology relies on incremental improvements to an already established technology. Disruptive technology lacks refinement, often has performance problems because it is new, appeals to a limited audience, and may not yet have a proven practical application. (Such was the case with Alexander Graham Bell’s ‘electrical speech machine’, which we now call the telephone.) In his book, Christensen points out that large corporations are designed to work with sustaining technologies. They excel at knowing their market, staying close to their customers, and having a mechanism in place to develop existing technology. Conversely, they have trouble capitalising on the potential efficiencies, cost-savings, or new marketing opportunities created by low-margin disruptive technologies. Using real-world examples to illustrate his point, Christensen demonstrates how ‘it is not unusual for a big corporation to dismiss the value of a disruptive technology because it does not reinforce current company goals, only to be blindsided as the technology matures, gains a larger audience and market share, and threatens the status quo’.2 More recent and relevant examples for libraries might relate to the emergence of the personal computer (PC), for instance. This was a hugely disruptive technology to the mainframe computer company IBM, who were dismissive that the humble PC would ever have any impact. They were complacent. In fact it ‘destroyed’ their central mainframe computing business. Bill Gates became a very rich man through the conversion of the IBM code into MS-DOS, a version suitable for the personal computer. It also created the software giant Microsoft. This story is detailed in the book Hard Drive.3 It is as Christensen observes: the large corporation could not see how the PC would fit into their business model and as a result of this, the PC destroyed their mass market business model. It is also useful to note that the PC had a wide-ranging effect on the rise of the ‘individual’: we could easily work on our own, in isolation from others and remote from the offices where IBM had us tied. The PC was a disruption with a manifold impact. ‘What if’ the PC had never happened? Can you imagine this? In the same way, in the next chapter we will look into the past in order to begin to see the future.

Another disruptive technology is the mobile phone. The mobile phone is now replacing the paper diary and book of contacts (the paper diary itself had already been disrupted by the PDA device such as the Palm), and is also disrupting the camera (the film camera had been replaced by the digital camera). So into the one compact device, the functions of diary, contacts, camera and now music storage and player are combined with the common function of a telephone. Businesses specialising in any one of the earlier technologies such as paper diaries manufacturers and distributors, camera manufacturing companies such as Kodak, and makers of cassette or record music players have all been disrupted in a very short space of time. The mobile phone continues to evolve to provide access to a host of information resources including, for example OCLC’s (the very large ‘consortium’ company providing bibliographic data to libraries) enormous catalogue, WorldCat, with its access to collections of more than 10,000 libraries worldwide.

The exercise accompanying this chapter will assist you to identify disruptive technologies and to examine their impact or their potential impact.

Broad disruptive technological impact on libraries

Assuming a broad understanding of the concept of disruptive technologies, it is now worthwhile thinking about the impact of digital technology on libraries.

In the mid 1990s it became possible for the first time to commercially deliver digital content via the Internet. Prior to this, digital content was restricted to the storage media of the CD (compact disc) and emerging into more compact but similar media. This was a huge move away from the microfiche as a storage medium. But even the additional capacity of the CD quickly became a problem and we saw the emergence of CD jukeboxes to cope with the number of CDs which were becoming necessary to store the content and the need to get to the relevant CD as quickly as possible. Of course, the CD’s data capacity quickly increased through the creation of dual-layered DVDs, making the CD jukeboxes themselves redundant.

The advent of digital delivery of content has had a profound disruptive impact on the library. The extent of this impact is, in many ways, not yet fully realised. With the growth of the capability of the Internet to deliver digital content to libraries it became possible for library users to use the library without even accessing the physical library building. This changing demographic of the library population is not a passing phenomenon but a growing one, leading to reduced turnstile counts. Fewer people are coming through the library doors, but paradoxically the use of the library is increasing and is increasing manifold. The physical library building is often turning to purposes other than the original model. There are coffee shops and community centres, and we have performance areas and retail outlets within the old library fabric. None of this is necessarily wrong but it is important that the library and information centre has a clear idea of where the organisation is heading as well as its purpose. Unfortunately, however, we have many libraries ‘losing their way’ as they struggle to find their raison d’être.

Digital delivery is fundamentally changing and disrupting the position of the library in its community. It is sometimes the case that the library is perceived by those communities to be irrelevant. It is openly wondered ‘why do we need a library when we have the Internet?’ While digital content is delivered to the user’s desktop via the Internet, the user can easily be forgiven when they do not even realise that the service is coming from the library via subscriptions. The users do not have, in this situation, any conception that the service takes a lot of organisation and that it does cost money, a lot of real money. The Internet is not providing access to this information at no cost. So the disruptive technology of digital delivery is and will continue to have a profound effect.

Library staff will, in this environment, not easily understand this impact. If their work is in the process of acquiring, collecting and making this digital content accessible, they will not easily recognise that their work has changed markedly. The impact on the whole organisation will be profound. The nature of their work in making content available digitally is changing. They are no longer working with ‘tactile’ information such as books and bound serials. Their work is largely unseen as the product of their work, digital content, is disconnected from the physical library. If the staff work in information services they will need to recognise the very fundamental change that many of their users are unseen to them. They are users in the virtual environment. If users are remote, staff will need a very profound change in their thinking and behaviours if they are to understand the information needs of these unseen users. These responses should be in terms of appropriate services and in terms of collection development. The ‘disruptive technology’ impact on collection development is one of the most important issues we face as we commence the twenty-first century. What we collect and make available to a largely unseen user population creates in itself many challenges, both intellectual and procedural. These impacts aside, the greatest effect of this is on the library staff, their work patterns, and their perceptions of the need to change organisational patterns, work behaviours and work design. These staff issues will be developed in a later chapter.

Issues in the wider environment

There are many issues shadowing the library environment which are having an impact on what can and cannot be achieved. The issues which are being explored in this chapter impact on all library sectors, in all geographic areas of the world. Invariably they are issues we should be aware of as they will impact on our future planning decisions and on the thinking, indeed rethinking, of all library and information services. It may well be that libraries will not be able to respond to or influence some or all of these issues and in some senses, this does not matter. What is critical, however, is that we understand what is broadly happening in our environment because only then can we decide with greater certainty where to take our strategic positions; where to point our strategies.

Open source

Bill Gates demonstrated great foresight and was indeed lucky to make MS-DOS code the operating system of the very early personal computers (PCs). The PC is now a very sophisticated machine but still the basic code or sets of instruction are proprietary. This DOS code, along with the software behind most of the major computer systems (Fortran, Sun and so on) is known as proprietary source code. Computer code directs the computer how to operate as a set of instructions. Proprietary code locks those instructions so that they cannot be changed without the permission of the software owner. History has rarely seen this type of situation, where crucial developments can be locked away. If we all worked solely on our own without connection to other people it might not have mattered. But this is not the case. We are very connected to each other locally and internationally. The extent to which we can connect or innovate with others is very dependent on what our computer systems will allow us. Proprietary systems are good if we never wish to change anything or if the manufacturer or software owner had unlimited capacity to change at ease. As the world is changing rapidly then software systems must also change at the same rate. Proprietary systems are dinosaurs for any innovating service. They are not responsive to connectivity or change. Because integrated library systems (ILS) have been written using proprietary code, the ILS as a library tool is closed, locked as an exclusively proprietary system. It has therefore been quite difficult to get any ILS to talk to other systems without great cost being involved. The systems are also expensive to develop as each system owner has to pay for the development of their own system including common elements. There has been a consolidation of these systems over recent years for a variety of reasons. In the 1980s there would have been more than ten main ILS vendors in the market. Nowadays there would be no more than four systems. It is a shrinking market. Among the reasons has been the entry of private equity companies into the library markets, generally attracted by the very solid and reliable cash flows. This entry has not seen the costs to the library decrease.

In many senses the world turns in circles. In the late 1970s library systems existed for two prime purposes: to automate and make cataloguing services more efficient and to operate circulation systems. A number of these modules were developed by one library or another and shared, for little or no cost, with other libraries. The story of these developments is a fascinating tale in itself; a story of great innovation and vision. Realising the viability of this new industry, library automation companies came into existence to develop the full suite of library service modules. But they developed as proprietary systems as this was the only way the software at the time allowed and of course for the profit motive as well. Now systems such as LibLime are hitting the market as Open Source systems, encouraging the free availability of cataloguing records as well. OCLC have also announced the release of their web-based ILS. The vision is to avoid each library maintaining its own software and server and rather relying on a central system (or OCLC) operating across the Internet, in the cloud as it were, making a host of other interlinked systems possible. At the same time OCLC are also seeking to tighten their ‘ownership’ of the records in WorldCat from further commercial use, so they will not lose future potential income. So the advent and growing popularity of ‘open source’ is beginning to have wider impacts.

Open Source software … permits users to use, change, and improve the software, and to redistribute it in modified or unmodified form. It is very often developed in a public, collaborative manner. Open source software is the most prominent example of open source development and often compared to user generated content.4

Linux is one prominent example of open source software which has gained widespread popularity. Open source enables users to develop software, to share it and to grow the capability of the computer programs without having to pay, and pay for upgrades. This sharing and collaborative mode is a fundamental characteristic of the Internet. The development of applications which can be shared between libraries and information services, enabling them to offer more innovative and effective services, is a new way of working. Equally, while libraries have had a strong and undisputed role in our society over the past number of centuries, this may not always be the case. The concepts espoused by Google to organise the information or to create digital copies of all the world’s literature could readily be seen to be ‘library concepts’. The point being made above is that proprietary systems have locked innovative development in libraries. The freeing up of the software through open source developments is an opportunity for libraries but it is also an opening for others to usurp the traditional role of libraries. The opportunity to innovate is not only for libraries but for anyone.

Open source is also now playing into the emergence of Web 2.0 initiatives. If Web 1.0 encapsulated the effective delivery of html documents to users, Web 2.0 is seeking to enable user participation through the capability of the Internet. It is providing software to enable interactivity of users to users, of users to information and of the effective interchange of information and user need across the vehicle of the Internet. So the conjunction of open source and Web 2.0 poses significant opportunities for libraries to position their services for greater effect.

If this book concerns itself with the future then we must consider the future development of the web, the influence of open source and the emergence of the Semantic Web. Web 3.0 could be described as Web 2.0 being driven by the Semantic Web and other emerging influences. If the traditional web presents information in our natural language, to be interpreted by humans and not machines, then the Semantic Web is the natural extension, having computers filtering and organising information with the direction of humans. The classic article by the founder of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee,5 on the Semantic Web is well worth reading. ‘The Semantic Web is not a separate Web but an extension of the current one, in which information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in cooperation. The first steps in weaving the Semantic Web into the structure of the existing Web are already under way. In the near future, these developments will usher in significant new functionality as machines become much better able to process and "understand" the data that they merely display at present.’6 Libraries are well positioned to design and inform these systems, perhaps in partnership with designers and innovators. Library staffs were composed until recently almost exclusively of professional, para-professional librarians and clerical staff. Now and increasingly, there will be other professional disciplines such as database managers, web designers, marketing managers, curriculum designers and event organisers. Diversity of employment types will be the key to getting the most effective library organisation. In this way, librarian skills will be more sharply defined and focused.

Open source implications

There are a number of implications flowing from the wide availability of open source solutions. Firstly, there is the move which is seeing more open source computer applications being available in the marketplace. This in turn is allowing for the ‘democratisation’ of software applications. Libraries in this environment can watch out for community developed software which might suit their information distribution needs.

Secondly, with the emergence of open source ILSs, libraries may consider the future of their proprietary library systems and the costs associated with them. In a time when the emphases are changing from the collection being physically bound to the library building to one where the collection is most significantly digital in nature and widely available, the library will have to consider where they place their systems development. It will almost certainly not be with the traditional ILS acquiring, storing and circulating physical items. The emphasis will need to be on innovative, inventive access and discovery tools for the digital collections and the need to work more and more on the Internet. If the traditional catalogue has been a ‘pull’ technology, then what the library needs is more ‘push’ technologies. A ‘pull’ technology is a static technology. It is there for people to use at their own need or pace. A ‘push’ technology can anticipate an information need and push the information to a user. An example of this might be where a library has created a profile of every library user’s information interests. With this profile, news of the annual of a new book relevant to a profile could be ‘pushed’ to the user.

Thirdly, if Web 1.0 existed to connect users and html documents, Web 2.0 is creating the interactivity between users and information with applications, often open sourced to enable and heighten that interconnectivity. Web 3.0 will see the development of the Semantic Web on the foundations of Web 2.0 initiatives but it will be driven by computers gathering and organising information according to the information needs of humans. What will the future role for libraries be in that environment? Will individual libraries or local library systems have the resources, let alone the capability, to compete with this technological advance?

Digital content

As the volume of information available on the Internet has burgeoned, growing at exponential rates, so too have the costs and copyright implications of the availability of this information become an issue. Traditional publishers, in making the content of their books and journals available on the Internet, have sought to ensure that their business model is sustainable. In moving away from a print-based business model where revenue flows and profit margins were known and reliable, they have embraced digital publishing but have sought guarantees for the future of their business operations. They have locked up the content for the lifetime of their authors plus 70 years.7 In addition, as they have seen the impact of digital availability they have made the retrospective collections also available in digital form, effectively putting this content under license arrangements where the user has to pay to gain access. The main legal issue in the future library operating environment will not be copyrights but licensing. The availability of print will stabilise at a low percentage of library collection while all the digital content will be licensed. The licensing conditions will be very definitive and restrictive, allowing for little shaping of content. The digital popularity of older content has been described by Chris Anderson, the editor of Wired, as the long tail.8 Effectively the theory and indeed the experience has been that, if you make older content available in digital form, it will be sought and retrieved by users. This observation is also a significant driver behind Google Books.9

As discussed in the Open Source section above, the emergence of the Open Access movement has presented challenges to both traditional publishers and librarians. Open access advocates argue that publicly funded research or writing should be publicly available as soon as possible. With a number of publishers, the compromise between commercial return on the investment in the original publishing and the commitment to open access is to make their content openly available six to nine months after publication. Still, these publishers are in the minority. The major publishers still lock their content behind firewalls and will no doubt continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Some publishers have adapted an open access stance that will allow immediate open access for an article if the article has been paid to be published, typically paid by the author. This cost is typically around US$2,500. This ‘pay to publish’ model in Western publishing will still have the imprimatur of peer reviewed acceptance. Chinese publishing already has both business models operating side-by-side. There is great pressure in Chinese universities to publish to achieve promotion. There is the capacity, however, to pay to publish without the quality stamp of ‘peer review’. Changes in this publishing paradigm will only happen with changes in attitude by the academic community as to where they wish to publish. Another key factor in this change will be how universities measure their quality outcomes. If they continue to use measures such as impact factors and citation analyses, they will strive to publish only in those journals which are perceived to have the greatest quality and prestige. This will have the effect of both renewing the same range of journals and also increasing subscription rates. So the drivers of the success of open access will lie significantly with the academic community, the drivers of peer review, perceived quality and competition between universities.

Digital content implications

The nature of digital content is having significant impact on library information tools, and will continue to do so into the future. Firstly, digital content is invariably favoured by the vast majority of library users, as they can access the information from anywhere and everywhere. This situation requires sophisticated proxy server environments in order to be able to deliver the digital content to the library’s defined community.

Secondly, the increasing availability of digital content on the Internet, through Google Books and other services, is highlighting that most of the world’s publishing content may be accessible across the Internet at some stage into our future. This will severely affect the role of the library and its raison d’être in the eyes of both users and funding bodies.

Thirdly, digital content from publishers will continue to exist and will represent the bulk of content provided through subscription or purchase, to library users.

Finally, the Open Access movement is building momentum to encourage the free availability of published literature on the Internet. This will impact the library-publisher relationship in three ways: it will encourage publishers to make the published versions of their material freely available after say an embargo of six to twelve months; it has and will continue to open the possibility of libraries becoming publishers in their own right; and it fundamentally changes the relationship between the author and the publisher. The issue of authenticity and credibility in published texts will be key in the future of this issue.

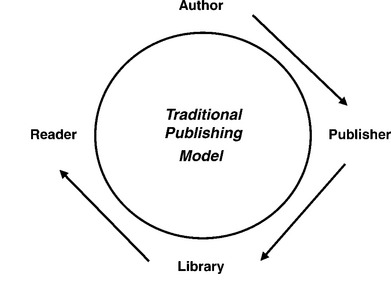

The author–publisher–library relationship

To understand scholarly publishing it is essential to look at the relationship between the author, the publisher and the library. The interplay is crucially important. In the traditional scholarly publishing model the author seeks a publisher and a journal and the library funds the journal for the reader. It is encapsulated in the circulate model above.

This effectively has been the business model for the traditional publisher. The advent of the Internet has offered the publisher new business models to go directly to the reader and bypass the library. These new business models are critical to their commercial process. This will be discussed further in Chapter 3.

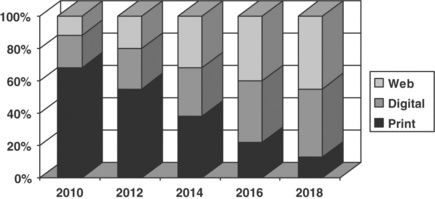

Content balance

Already the nature of the content being collected by each library is changing. Digital content became available on CDs in the late 1980s and gradually via the Internet in the early 1990s. So libraries began collecting their content in digital form and the amount of print material fell. It has, in certain library systems, continued to fall. But what is the mix now and what is it likely to be in a few short years? Whatever mix is now evident, each library system will shape the type of building and facilities which are required; will shape the computer/Internet infrastructure which is required; will shape the budget which is required; will shape the staff skills which are required; and most importantly, will shape the perception which a library’s users have of that library service and its future. In a similar way, the different disciplines served by the library will have different informational needs. They will each have different delivery mechanisms. Science and technology disciplines will most likely have their information delivered via on-line journals; social sciences and humanities will have a mix of e-journals and e-books as well as print books.

The future of work

In preparing for the future we have to consider the future organisation. This is the vehicle through which the future scenarios are to be delivered. Invariably, organisations are shaped by the tools they have to deliver the organisation’s mission. Large organisations can be very difficult to change as they have perceptions of their aim, role or position which are largely directed toward self-sustenance. A large organisation with large powerful departments can find change almost impossible to achieve. Yet small companies with the new computer tools and the availability of the Internet can have a far greater impact than their size indicates. They can create niche businesses where there was no opportunity before. A small start-up can be more nimble, progressive and swift than a large bureaucracy. The nature of work and work patterns are helping this to occur. They are also driven by the skills of their people.

The point, mentioned earlier in this book, that IBM completely missed the disruptive influence of the personal computer is a key observation to understanding the issue of work. In designing work flows, the PC is still supreme and a large expenditure item in the capital and maintenance budgets of our libraries. The financial tsunami of late 2008 and early 2009 will have work implications for many years to come. Apart from placing pressure on the availability of work, it will also sharply impact on the way in which we actually work; it will heighten new ways of work being organised for groups or as individuals. Businesses surrounding our library will re-examine their existing operations for effectiveness and profitability while new businesses will also emerge from the opportunities created by this severe economic downturn. The issues raised earlier in this chapter and indeed in Chapter 1 have highlighted the seismic shifts in the patterns of information delivery. If the major uses of the library service are occurring remotely, then how should we respond? Do we focus on what we know best, do we race and change everything, do we engage partners, do we encourage others to deliver certain services while we focus on other areas?

Implications for the future of work

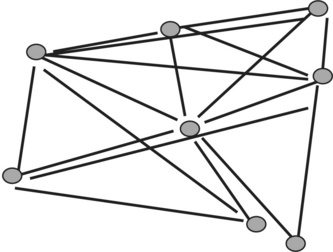

The disruptive technologies mentioned earlier in this chapter will have a strong effect on the shape of the resulting library organisation. It is a matter of ‘seeing’ these changes and trying to understand their likely impact. Organisations today are clearly not as hierarchical as they were, say, twenty years ago. There is an openness to their operation and decision-making. Some describe this as self-organising, consensus decisionmaking, empowerment, democratic, even flattened organisational structures. There is a greater degree of participative decision-making in the workplace. But in what direction is the workplace now going? The Internet poses opportunities for staff to work away from the organisation’s theoretical headquarters. To work at home has realised many advantages and cost savings to the organisation but has created other problems such as a diffusion to the organisation’s purpose and direction as well as personal isolation. Still, this trend to off-site or at home work is a reality and has to be assessed as to how it can be used in one’s organisation. The Internet also shapes the nature of the work we do and therefore the way in which we organise ourselves. John Malone, in his book The Future of Work, argues for the various models of organisation on a continuum from independence, through centralisation, to decentralisation. A common experience in public and academic libraries over the past ten to fifteen years has been the merger of local councils and higher education institutions and the resulting impacts on previously independent libraries. Will economic pressures force the larger organisational units, to which libraries invariably belong, to seek to remove middle management and to aggregate smaller units to achieve perceived efficiencies? These trends have been common over the past twenty years and are not likely to disappear in the near future. Independence still exists for libraries, notably special libraries, but for all of us, there is a far greater sense of strategic inter-dependence. Even those libraries which exist within centralised systems experience the interdependence of their system with other systems. The diagrams below are modelled on the work of John Malone but are just as effectively applied to our library environment.

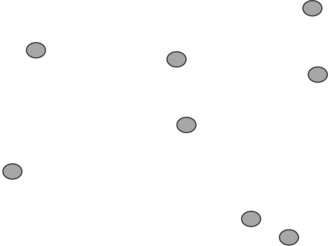

Independent libraries

Independent libraries exist without much connection to each other. Invariably they exist in an environment in which they might accede to certain standards of performance (e.g. MARC records) but otherwise have separate, autonomous existences, organisational hierarchies and strategic imperatives. Some of these libraries may also have branch libraries but the systems are theoretically independent.

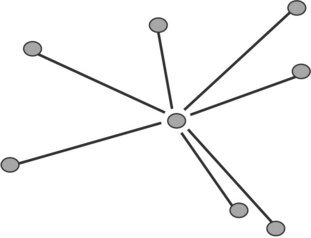

Centralised library

The centralised library exists where systems are larger and more complex but where there is far less scope for independence of the member libraries within such systems. Each of the libraries owes its existence and funding to the central operation. Even in this model each of the libraries can maintain some degree of autonomy and proud independence. But, in the end analysis, they have to work with the centre because without resources they will wither.

Networked libraries

The new networked or Internet level of connectiveness has opened new ways of organisations working to achieve their outcomes.

It is into this networked, connected world that libraries will find themselves moving more and more. The style of management used in a hierarchical, independent environment will be very different from the management style which will be needed to be effective in a networked or consortium environment. The managers who are used to being in charge in their home environment will need to adopt much more consensual approaches as they work with peers from other library systems. Complicating matters is that the peers in a networked environment will not necessarily be from libraries of equal resource dimensions and yet they will carry equal influence in this new environment. Even the largest libraries need the support of the smallest libraries in this networked environment if they are to succeed. Examples of this are where physical resources are shared across different library systems, so that the user gains the advantage. All library partners in such a situation gain advantage, politically and operationally. Library users do not care where the resource comes from. This is especially the case where the service operates across the Internet. The outcome which is transparent to the end user is the delivered information product whether it is a physical book or a digital information package.

The number of consortium organisations in the library world today will steadily diminish over the next ten years, but they will be more powerful organisations carrying significant responsibilities for the libraries in their membership in this networked world. Consortia organisations are not a library invention but their role and character is peculiarly suited to the library and information environment.

In the world of library and information services there are many different organisations which are tagged as a ‘consortium’. These will range from local groups established to assist groups of libraries to work together, to one such as OhioLINK, which was established to assist libraries in the state of Ohio, USA to spend state and university funds to purchase datasets together. Some organisations such as CAVAL, Victoria, Australia were established to provide cooperative cataloguing and then grew to a number of other functions including cooperative storage of low-use research materials. OCLC is the largest of all ‘consortia’ although it is difficult to agree that, at a turnover of over US$50 million each year, it is actually a humble consortium. SOLINET is a genuine consortium with over 3,000 library members spanning an increasing range of states in the USA. The trend, already mentioned, is that there will be a consolidation of consortia. PALINET and NELINET have now merged with SOLINET to form the new group LYRASIS.

It is not intended in this chapter to detail all consortia, their nature, governance and purpose: suffice it to say that the consortium is a legal device to enable libraries to work together to achieve a common purpose.

Emerging trends

If anyone were to doubt the power and utility of the Internet, the inauguration of Barack Obama as the 44th President of the United States provides a few salutary lessons. ‘Ratings show that the January 20 inauguration was the first time that more people tuned in to a live, high-profile event on the Internet than on television.’10 But in this context, what are the issues which matter to your own library?

Later chapters will examine techniques by which the future can be assessed and, to the extent possible, managed. However, looking at libraries at this point in time, a generalisation could be made that the average age of staff would be quite high. If this is the case then a number of observations would follow.

Firstly, there are many potential employment and progression opportunities opening up. Secondly, the current leadership may be finding it difficult to relate to and understand the needs and outlooks of the younger user, and indeed staff. Generational change brings its challenges but also its prospects for new insights and contributions. In this situation the existing leadership and the new library generations have a mutual benefit in truly listening to each other and, of course, to their users. We now have a new young President in the United States holding the prospects of new ways of dealing with the future.

This chapter has examined the main trends affecting libraries as they decide on their future directions. The emphases and the detail will be different for each and every library system. Later chapters will build on this work.

1.Rowling, J. K. (2007). Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. As cited in http://www.quotationspage.com/quote/33790.html(accessed on 14 February 2010).

2.Available at: http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/0,,sid9_gci945822,00.html (accessed on 6 February 2009).

3.Wallace, J. and Erickson, J. (1992). Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the making of the Microsoft empire. New York: Wiley.

4.Open Source Software. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_software (accessed on 11 February 2009).

5.Berners-Lee, T. (2001). ‘The semantic web’ Scientific American, 17 May. Available at: http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=thesemantic-web&print=true (accessed on 15 February 2009).

6.Ibid.

7.The period of 70 years has only recently been extended from 50 years under international copyright law. It is likely to be extended further into the future.

8.Anderson, C. (2006). The Long Tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more. New York: Hyperion.

9.Google Books is a major project to digitise much of the world’s print books in cooperation with many of the world’s largest and best libraries. There are similar projects emanating from many large library collections, such as the New York Public Library.

10.‘TV industry needs to log into the future’ South China Morning Post LXV(33): B10 (4 February 2009).