Defining a purpose

Abstract:

Library managers and leaders can connect social media to the organization’s mission by setting goals and providing a focus for organizational members. Managers need to consider how services are unfolded and how they will be adopted by organizational members. Many social media tools will be treated as gadgets that do not directly impact organizational goals. Defining a purpose around social media helps to directly tie the technology to the need. Libraries can join the larger conversations that are already happening in their communities. Social media can enhance connections to community groups, spread library-related news, and capture library-hosted events. Social media can also become the infrastructure for networked decision making, which overcomes the limits of past, top-down approaches to decisions.

Introduction

My wife does not like onions. This is one of the ongoing challenges in our relationship, but we have learned to deal with it. When we swing by a fast food restaurant for a burger, I have come to understand the challenge of ordering a cheese burger with no onions. Even though I enjoy onions quite a bit, I have learned that being married to a non-onion- eater means that the existence of onions can negatively impact my own meal. Thus, ensuring that onions are not placed on my wife’s food becomes important. When ordering, it is important to repeat the request to remove onions from the sandwich at least twice. The first time should come immediately after requesting the cheeseburger. “I’d like a cheeseburger without onions.” The second time should be at the end of the order right before paying: “Just wanted to check to be sure that you hold the onions on one cheeseburger.” Then, before sitting down or before taking the food, it is important to check the specific cheeseburger to ensure that onions are not there. This strategy improves the odds of getting a personalized order in a fast food restaurant from around 50 percent to about 80 percent.

The reason for this is obvious to most of us. Fast food chains are highly standardized. They standardize their process in order to reduce mistakes by employees and to ensure food quality and appearance at thousands of establishments around the world. Of course, the problem faced by my wife—and me by extension—is that she does not enjoy this standardization and is in the difficult position of trying to force this system to do something different. We have concocted our own specialized approach to ordering so as to increase our odds of success. Of course, my personal strategy is to like onions, so my order is always right. However, I have learned not to suggest this strategy to my wife.

Any time a user accesses a service, a significant amount of the interaction will be predefined by how the service is offered. Were I to visit a tailor, get measured, pick out cloth, and describe what I want, the tailor could create a one-of-a- kind suit just for me. On the other hand, I could drive down to my local wholesaler, look through racks of identical suits and select the one that most closely matches my size and taste, even if none match perfectly. Most services can be considered on a continuum between highly personalized and highly standardized.

When a customer goes into a standardized service, the customer must learn how they will interact with the service. The individual who accesses a highly personalized service needs to know very little, because the service will adapt exactly to his or her needs. The individual who accesses a highly standardized service needs to understand how and to what degree the service can be manipulated to reach his or her needs.

When a customer goes into a standardized service, the customer must learn how they will interact with the service. The individual who accesses a highly personalized service needs to know very little, because the service will adapt exactly to his or her needs. The individual who accesses a highly standardized service needs to understand how and to what degree the service can be manipulated to reach his or her needs.

The Starbucks chain of coffee shops is a fascinating example of balancing standardization and personalization. They have many, many options for changing their drinks. Each option is standardized, but there are so many options that it is difficult not to feel that one can order a one-of-a- kind creation, such as a half-decaf, grande, soy, mocha with a shot of vanilla. Their baristas manage the range of options by having a standard ordering process that roughly follows this outline: iced/non-iced, size, type of drink, and any special flavors to be added. If a customer orders coffee in the wrong order, the barista politely says the order back in the correct order as a friendly instruction for next time. I purposely order my drinks out of order just to see if they can handle it, “vanilla, skim (they don’t use the word “skim” for anything), latte, grande.” This drives them nuts.

My ordering like this results from my own mischievous nature, and I am probably guilty of enjoying the difficulty I cause people who are just doing their jobs. Of course, the point of this system for ordering coffee is to gain efficiency and limit mistakes. In order to do this, the system doesn’t just train employees, but it also trains users. The reason the barista repeats the order back to me in the correct sequence is to influence my behavior so that I can order correctly next time. For some reason, I gain pleasure from pushing back a bit against this system.

There are lessons here for librarians. We too have a choice about the degree to which we standardize or personalize our services. Whether or not we know it, we think about this when we talk about the length of time librarians spend with a user at the reference desk. We also think about this when we create online guides, signage or information literacy sessions, all of which encourage users to be independent. Some days our librarians may be able to work with users for extended periods of time, giving them very individualized service. Other days, we are too busy, and librarians must perform triage in helping users, where we weigh needs and distribute our time. We always want our users to be independent so that they can access our services without our help. But this means that users must find ways to learn our systems and break through the layers of processes and rules we have in place. Ideally, we would give users very individualized service meeting their exact needs, but we know that this is not always possible.

When we think about social media and how we offer our services, we must think about how we unfold these services. How will we personalize our connections with our users, and, just as importantly, to what degree will we expect our librarians to act as individuals? We must decide whether we expect our social media services to be individual librarians connecting with individual users or whether these services will be a generic library voice broadcasting out to many users. There is a spectrum here in how we can break down our services. We can also think about how social media can work across our existing services to cut through some of our own standardization. We can use social media to connect in new ways that may allow us to step beyond our own walls, processes and ways of thinking.

Technology adoption

In Megatrends, John Naisbitt (1982) defines three broad phases for technology adoption within a culture. In the first phase, the new technology follows the path of least resistance. Users play around with it and try it out. I have also heard this called the gadget phase. The new technology is largely a novelty that shows potential, but has not really altered the way things are done. I remember signing up for the social networking site Hi5 back around 2005 or 2006. I signed up, created an account, and even invited a few of my friends to join. However, most of my close friends were not actively using social networking sites. They were definitely not on Hi5. After I signed up and made a page, I kind of sat there and wondered what I should do next. There wasn’t much to do. I was about three to four years away from most of my friends and family posting every detail of their lives via social media. By that time, of course, they used Facebook and not Hi5. In 2005, social networking was definitely in the gadget phase for most of us. It was something to tinker with but not really something with a major impact on our lives.

In Naisbitt’s second phase, users adopt technology as a replacement to improve things that they already do. In this phase, the technology makes life easier as it displaces older technologies. For instance, messaging in social media sites has largely replaced letter writing and even some volume of emailing. I remember feeling very empowered back in the early 1990s when I received my very first calling card. I could use any payphone to make a call, and the charges would be placed on my home phone account. Now, it is impossible to find a payphone. Cell phones have made public payphones obsolete along with my calling card.

In Naisbitt’s third phase, the technology becomes transformative. The technology enables a whole new set of actions that could never have been done without it. Facebook has brought together email, chat and discussion boards, but it has taken these a step further. The ability to combine location data and to connect Facebook with external sites has made sharing seamless. They have enabled a degree of interactivity across the web that was not possible in the past. It’s not that sharing didn’t happen, but it couldn’t happen like it does today.

As managers and leaders, we have to recognize that many technologies will exist in the gadget stage for a long time. Some will grow and move beyond it, but others will not. The gadget phase may sound unimportant, that it is something silly or childish. Leaders and managers overlook and undervalue the gadget phase. They often do not even recognize when it is occurring, and they rarely encourage it. But, the gadget phase can be very important. This is the time when new technologies gain attention and demonstrate potential. The seed is planted.

Over time, social media tools will come and go and many of them will never move beyond the gadget phase. For some tools, this is because their functionality may not align with staff needs. But for some tools, the functionality may be very useful, and staff may still avoid them. This is because really engaging users in social media requires librarians to move into the arena of ideas. Engaging users in the realm of ideas has inherent risks to employees such as entering controversial debates and potentially angering one side or the other. Most employees are savvy enough to avoid conflict and not risk workplace conflict. Therefore, they avoid truly developing many tools. They may tinker around with social media tools, but they do not really use them to actually engage users. They carefully steer clear of risk and keep the tools on a permanent back-burner. Confusion around the level of the service complicates this. Are librarians accessing social media tools as individuals or are they creating department- based accounts?

Organizational members need clarity around social media. While they do not need to be told exactly how to use each and every social media tool, they do need to have some context around the tools. Part of this context needs to address the level of service or the level of connection that the library will make via social tools. This may vary depending on the tool, but without guidance, most social media tools will be doomed to haunt the gadget phase forever. Managers and leaders must recognize that enabling action requires context and context requires a definition of purpose. What is the value of social media tools for our organization? Answering this question identifies our purpose.

The difference between marketing and community

The simple notion of liking something has become powerful. “Your friend likes this” grabs our attention because our friends often share similar interests. Naturally, this is a marketer’s dream come true as users self-identify as liking a product, service, person, institution, article, video, etc. and then pass it along to their friends who may also connect with it. PR firms have long known that a significant portion of advertising revenue is wasted because it does not reach its intended audience. Newspaper and television advertising have been extremely inefficient because the only way to reach the small percentage of people who will use a product is to send the message out to everyone. Social media are changing this as users help to spread the word to their friends. Of course, marketers also know that nothing turns off users more than an inauthentic experience. Fake people and fake videos can cause a backlash. People do not like to feel like they are being duped or being played for a dupe. Marketing experts continue to seek out the elusive authentic experience. Connecting customers to products in authentic ways pays big dividends. Think about the success Apple has had in turning its products into something more than just technology tools. The company is marketing ideas around a lifestyle as much as it is marketing consumer electronics. PR experts are recasting marketing as an exchange between user and product, not as a one-way broadcast about a product (Lefebvre, 2007).

Libraries are better positioned to offer authentic experiences than most marketing firms, because we are authentic. We seek out actual needs and are not trying to sell anything. I have been to many marketing workshops for librarians where participants are given a big packet of marketing materials and told how to make a marketing plan. Now, I’m sure the people who run these workshops are very intelligent and I’m sure the information they present is really useful, but there are a few things that I never hear them say. I never hear them say that every contact made with the public is marketing. I never hear them say that the best marketing a library can have is the absolute greatest service. Instead, it is as if there’s this unwritten belief that a library can market its way to success. The reality is that doing our job to our best abilities is the best marketing we have. Social media tools should be the tools that we use to do our jobs. They should be used to help our patrons reach their goals.

There is a difference between marketing and community. Marketing is communicating value in an effort to extend services, which is important to libraries. Community, on the other hand, is about engaging users and being part of their lives. Community is a give and take. It feels more like being a neighbor. This distinction should not escape libraries. Apple has done a brilliant job of manufacturing community around its products, but for us there should be nothing to manufacture. The community is out there. We just need to consider how to make connections. Yes, libraries need to market themselves. But, the purpose around social media should be more than marketing. It is not possible to overstress the need for community.

The first step in defining purpose is to consider the value that social tools offer. This value can help us consider how standardized this service should be and how we can move tools past the gadget phase and toward more innovative uses.

Joining the conversation

The most compelling reason for libraries to engage in social media is to join the larger conversations happening around them. Drawing on our information resources is a significant way for this to happen. From their inception, librarians have played the role of information filter. Our essential role of collecting information for communities of people has remained unchanged for centuries, even as the ways we perform this task have dramatically shifted. Our society still has a need for us to be access points for information. This remains especially true as long as specialized content still has a cost attached to it (purchasing physical items, purchasing access to online tools, or supporting the infrastructure to access, such as internet access). This also remains true as long as significant portions of the population cannot afford to purchase their information.

In libraries, content should remain king. Social media can be utilized to maintain this focus as we can now show off and promote content as never before. This may take the form of book reviews, virtual book groups, connecting users to video or articles that enhance popular books, and many other avenues. We need to find the people who love reading, parents and students who need support, job seekers, community members who attend our events, activists working on local issues, neighbors of our branches, hobbyists using our resources and leaders of library friends groups. Every one of these groups is a potential audience for us to engage.

When it comes to joining the conversation, there is no better tool than a blog. Blogs allow for article-length pieces that are initially organized by date, but can also be categorized and shared. Blogs allow for thoughtful discussion around any topic, pulling in references to books in a collection, articles via databases, or embedded video from streaming services (Figure 4.1). This a great way to create and capture knowledge.

Another simple approach that could have a local impact is to set hashtags around local issues in Twitter. Hashtags operate like a subject label, pulling together tweets that share the same tag. This is a way to initiate a discussion on an issue by people who do not follow each other. It is a way to organize a larger conversation around an event. Twitter is great for live events like sporting events, political speeches, or protests where hashtags can be used to bring together real-time conversation. During the 2010 FIFA World Cup, there were country hashtags such as #arg, #mex, #fra, #eng and #nga. There was also a general World Cup tag which was simply #worldcup. Readers could follow conversation around one country or follow the larger conversation.

Hashtags have no rules and no central mechanism for approval or disapproval. They are simply created when someone types them. That’s it. Hashtags come and go. They are like library subject headings that have broken free of our classification schemes. Tags are sloppy. Multiple tags refer to the same subject. They can be difficult to discover. On the other hand, they are easy to make. They are organic. They are extremely responsive. They tend to be used more when a recognized organization or individual connects a particular tag to an event, which is a perfect role for libraries. This could be as simple as using #LondonRdConstruction when tweeting about a local road improvement project or #headingtonschools when discussing local school issues. As a tweet can include links out to the web, this is a great way to share articles or links to a library blog for a more in-depth conversation.

A platform like Tumblr crosses the turf between a standard blog and Twitter. Compared with Twitter, Tumblr allows longer posts and embedding of content like audio and video. It also comes with a community of users who can easily share and move content. Tumblr is not as encompassing as a traditional blog like Wordpress for longer posts, but it is easy to implement and perfect for short posts. Tumblr could be great for quick content around projects that may include images or embedded video. Images from the local archives or even photos from your librarians’ visit to a local museum would make great uses for Tumblr.

In all of these examples, the library staff member must be knowledgeable about the community and have content to contribute. For many staff members, the technical side of social media does not present the most significant challenge. Many staff members fear the actual content more than they fear the technology. Having something to say can take work and some risk. This requires stepping into the role of content creator. It also requires recognition that the purpose of social media is content generation.

Generated content vs curated content in a fact-checking world

A great deal of debate has been happening around the transformations occurring in journalism and the increased role of citizens as reporters in their own communities. The debate is important and warranted as local news outlets vanish into the night. Ironically, this technological shift is occurring as the information glut overwhelms us. As publishers and news media are disintermediated, writers of all stripes are pushing information online. Readers are left to fend for themselves against the onslaught. David Weinberger (2012) describes a crisis of knowledge as institutions and publishing structures that lend authority and credibility to information are undermined by the online world. Any opinion and crazy idea in the world can find support and “facts” somewhere on the web. The web has unleashed relativistic chaos where any idea is just as good as the next. The institutions that have supported public discourse over the years are being redefined and new institutions are being developed.

As a result, many news organizations have started to launch fact-checking services in an attempt to tame the avalanche of facts used in the political sphere. Sites such as the Fact Check Blog from Channel 4 News (http://blogs.channel4.com/factcheck/.) in the UK and Politifact from the Tampa Bay Times in the USA, attempt to check the numbers and weigh in at times when political leaders bend data to meet their needs. Any regular citizen of the web knows that myth-busting sites like Snopes are essential to sorting through the bias and flat-out misinformation that proliferates on the web. Weinberger (2012) notes the irony that at the same time that the web makes information delivery effortless, the effort it takes to sort through the discourse makes the information unusable. We are living through a utopia and dystopia at the same time.

There is an opportunity here for libraries. We can be islands of order in a tumultuous sea. To some degree, journalism and libraries may walk down the same path as arbiters or brokers of information. Libraries can join the discussion by offering resources, discussing credibility, and acting as grounds for healthy debates. As noted in Chapter 1, filtering information is an important strategy for managing the information glut.

Ironically, filtering content by curating collections is what librarians have been known for over the last few centuries, but most local libraries have not engaged in online curation to a large extent. Social media may be an avenue to make this manageable. First, we have to consider that “curation” may not mean cataloging to MARC standards. It may mean organizing content in more temporary collections that are put together for short-term needs. It may also mean longer- term collections of digital content.

There are many organizations in local communities who have an interest and need for short and long-term content. Local historical societies, museums, religious organizations, schools and youth organizations can be supported through mini-collections. On college campuses, this might include academic departments, theater groups, student organizations, college initiatives or college administrators. In all cases, collections of sources, annotations of sources, or longer write-ups can give context and support for activities. This may be as simple as posting a single link on Facebook in support of a new college initiative or posting a link with additional information on an exhibit at a local museum. This also could be more in-depth collections that require formal organization and explanation.

Curation activities can go beyond simple distribution of links for local organizations. Many of these groups have their own content to contribute but do not have the infrastructure to make this possible. The local historical museum may have digital images or documents that can be digitized and shared. These could be uploaded, annotated, shared via the web and even organized with metadata. Groups in the community have a great deal of content to contribute if the library has ways to seek this out. Library leaders must consider whether librarians or staff members will gather and upload content or if community members will contribute content themselves. Curated content may be organized and posted using a social bookmarking tool like Delicious or shared via sites like Reddit or Stumbleupon that aim less for long-term access of information.

Part of the value that libraries can add for these community groups is establishing credibility, recognition and awareness. Naturally, as curation projects move forward, we must recognize that what is not collected is as important as what is collected. Care must be exercised as librarians determine the length of projects and the level of ongoing support that the library will provide. Social media and the web provide many options for making content accessible to the public. Some options are inexpensive and easily utilized by lone individuals. Other options require more technological support and planning.

In the past, information creation and distribution was expensive, so libraries remained in the collection business and out of the creation business. As physical media have given way to digital, the lines between creation, collection, distribution and storage have blurred. Just as journalism is moving toward hyperlocal and citizen journalists to collect and curate content, libraries have similar opportunities as we recognize that content is not something that comes from publishers, but is something created all around us.

News about the library

One clear-cut and very useful purpose for social media is spreading news about a library’s services, events, facilities and staff. Most libraries are engaging in this via email, social networking pages, blogs and information on their websites. As local newspapers have cut pages or folded altogether, libraries have been spreading their message using the effectiveness of the web. With social media, it is easy to make a fairly attractive page.

With the rapid spread of social media, managers and leaders must recognize that all library staff have a role to play in disseminating information about the library. Our organizations are very active, and members in each department may produce “news” that they want to get out to users. There is the potential of a cacophony of library voices clogging Facebook pages or posting to blogs. Ironically, in many libraries, the posting of news falls to one, lone voice, often the poor person who started up the library blog. This person must know about and understand the significance of newsworthy items and then have the time and energy to write up posts. The advantage of libraries’ loosely-coupled nature is missed. (Chapter 5 deals with these challenges.)

A question facing managers and leaders is whether the library has an official news channel or whether librarians and staff members are free to publish news. Do department heads, professional staff, or others need approval from supervisors? Does news need to be filtered and checked for accuracy before it is published, and what kind of delay does this review put on the publication of news?

On my campus, our library is fairly free to use our blogs, campus email and other social networking tools to spread news about the library. The college also has a public relations department that acts as the “official” voice of the college. I can submit draft press releases or just details about events and services. The PR staff members review my submissions and weigh them against the larger needs of the school. Most of the time, my submissions make the cut and are distributed. Nevertheless, there are times when my information may not be included. When that happens, I rely on my library’s social media tools to spread the word. I know that local news outlets (online and in print) and other local groups who share information pay more attention when my information comes directly through the campus PR office, which manages the college’s main Facebook and Twitter accounts and have more followers than my library’s social media pages. Depending on the size of the library, leaders and managers may want to consider the role of department pages versus a library-wide page. Does the library need a way to decide what counts as news?

Capturing events

As discussed in Chapter 3, social media’s impact has been greatly felt by protesters and activists. For them, protests have become as much for online consumption as they are for the actual time and place. They are using social media to extend protests into the virtual world, giving them a life that carries forward beyond their temporal existence. Libraries can learn from this. The promotion of cultural events and programming offered by libraries definitely falls into the news category, but capturing these events and moving to the online world is something different.

Lectures, children’s programs, art displays, book talks and other events can get additional exposure and life through the web. As discussed, the most basic and perhaps essential way that social media can support programming is through promotion. Blog posts, tweets and Facebook posts should be basic operating procedures in promotion.

Social media can easily enhance events with online support. This could include short written pieces that link to books, articles or other information sources. These may include artist statements for art exhibits or historical notes to add context to musical performances. It may include the incorporation of location-based tools such as Foursquare to spread the word about events as they happen.

People love images. The use of images online has become increasingly easier as cameras on mobile devices have improved and the costs of digital cameras have come down. Uploading images to Flickr or creating albums on Facebook is pretty easy. Sending out images after the fact is a way to capture some of the event as documentation to show that libraries are doing their jobs. Images are also a way to remind people who were there about the success of the program and to show off the event to people who did not attend. It is a way to say, “we do these kind of events, so keep an eye out for more in the future.”

Another enhancement for cultural events is the use of hashtags in Twitter. This is a great way to encourage the audience to engage with live events in virtual space. Audience members who do not know each other can use the same hashtag and comment and hold an online discussion in real time. I have been to many conferences where the organizers predefine the hashtag and participants then tweet notes and images from presentations. This is great way to have audience members filter information as it happens. I have to admit that I have followed many conferences from my office via Twitter, because I could not spend the money or time to attend. Hashtags can turn anonymous audience members into a valuable part of the event.

Along these same lines, Twitter can be used to bring people together as a “Tweetup.” This is a meet up of people who tweet around a topic. It turns the physical world into a complement of the virtual world. Tweetups tend to be more successful in instances where people care deeply about a topic and have a rich, online discussion. Rich online discussions bring people together to have rich face-to-face discussions, and, of course, additional tweets about the Tweetup. Libraries can organize Tweetups and encourage these events.

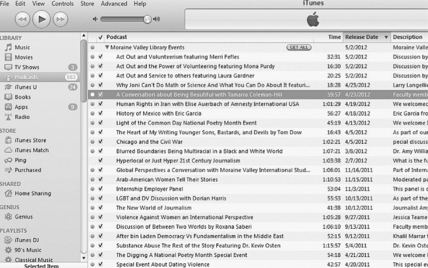

When it comes to extending an event into the virtual world, images of events and supporting information about events add value, but they are not quite the same as the event. Social media present opportunities to distribute the event itself. The most straightforward would be videos of events posted to YouTube or distributed as a video podcast (Figure 4.2). Video does not replace the actual event, but video does allow discussions, lectures and presentations to be captured and shared. For nearly a decade, blogs have been used to “live blog” events. This means that a predesignated person types out notes about an event as it happens. Before bandwidths grew and before streaming video was common, live blogging was the best option for real-time, online broadcasting of events. Libraries can still do this very easily and inexpensively.

Video files can be large. They require a bit more knowledge in terms of recording, editing, storing and uploading. If video feels a bit out of reach, audio may be more manageable. There are many affordable MP3 recorders that can be used to record discussions. The MP3 file format has proven to be very versatile. MP3 files can be linked to in blog posts, they can be uploaded with a static image to YouTube, and they can be turned into a podcast for distribution in iTunes. Free audio editing software like Audacity allows for the editing of files. The audio of an event misses the visual elements, but audio is easy to manage and captures the key content for most events. Audio matched with a PowerPoint presentation can be quite effective.

A step beyond capturing events would be organizing fully virtual events. Large-scale live events can be difficult, requiring a streaming server and technical know-how. However, there are many more accessible options. Skype can be utilized to bring together individuals for an interview that is recorded for later distribution. Google Voice or Audacity can be used to record phone conversations that can be turned into a podcast or online recording.

In some ways, cultural events and programming are low- hanging fruit for libraries. They represent valuable content and information sharing. Events engage the community and bring people together to share ideas. Events turn the library into a public learning space where discussion and sharing thrive. Most libraries already host events, and social media can be used to extend the events and broaden their impact.

User contributions

The possibility of libraries curating content from community organizations is discussed above, but this can be taken further. Talented individuals across our communities have contributions to make. Guest bloggers such as local political leaders, local educators and local religious leaders could write about issues and activities in the area. Librarians could invite original contributions from leaders, or they could keep an eye out for exciting pieces published in community newsletters or local blogs. With permission, existing content can sometimes be “repurposed.”

Crowdsourcing has become a popular idea on the web. Crowdsourcing uses the web to distribute work among many people, each of whom contribute a small portion of the work. This enables the crowd to accomplish tasks that would take individuals a prohibitive amount of time. In the UK, The Guardian famously initiated a crowdsourcing project when it recruited the public to help review nearly 500 000 pages of MPs’ expenses claims to examine how MPs were using public money. Libraries may want to avoid divisive political debates, but they could take on other projects such as posting old photos to Facebook and asking users to identify individuals.

Many integrated library systems are following Amazon’s lead by allowing users to write reviews of books and other resources in library collections. The local tool for this kind of work is a reader blog where users submit reviews about their favorite books. Book group members can offer write- ups before the book groups meet. Readers are lovers of ideas and often looking to find others who love their favorite authors and characters. Virtual book groups can be organized in social networking sites such as Ning where individuals can post to their own blogs but also share on discussion boards. Facebook pages can be created for particular authors or particular themes. Users can help to curate links, but they can also contribute their own, original ideas.

Capturing internal knowledge

Several years ago, one of our librarians at our reference desk received a call from a college staff member asking about Public Law 195. They told us that this law required our students to pass a test on the Illinois State Constitution (where my college is located). There was a reference to Public Law 195 in college documents, but college staff could not find the law or any additional information. A Google search revealed that other colleges in our area also reference Public Law 195. After a great deal of research, including several phone calls to government agencies, our librarian learned that there was no such thing as “public law.” We had “public acts,” but there was no Public Act 195. We didn’t know where Public Act 195 originated, but it did not refer to anything legally binding. Our librarian did find reference to requirements for students in lower grades taking a test on the Illinois Constitution, but nothing clearly about requirements that might impact our students. This research took many days to track down and confirm from individuals in the state. In an effort to document this work, our librarian posted it to one of our library’s blogs (Public Law 195, http://ext.morainevalley.edu/searchtips/?p=313). For many years, this blog post was the first result returned by Google when one searched for “public law 195” (at the time of writing, the post was at number 6). The post was also shared via email among our local colleges.

This post about Public Act 195 is a classic example of useful information being created, captured and shared on a blog. As discussed in Chapter 3, an advantage that social media offer to our libraries as loosely-coupled systems is the ability to capture and share internal information. A reference blog is definitely a perfect tool for showing off searches, reviewing new resources and pointing out search tips to users. More concise posts could be made to Facebook, Twitter, Google +, Tumblr and many other platforms. Information services, reference advice and the identification of useful tools remain at the heart of what we do, and we should take every opportunity to show them off—not only are there marketing benefits, but this makes our services carry on long after the interaction has ended.

Beyond reference, social media present ways for staff to stockpile organizational knowledge. Wikis are extremely useful for organizing and editing policies and procedures online. Wikis can be hidden behind a password so that they are not open to the public. They are easily edited so that they can be updated over time. The fact that they live online means there is no worry about which version is current or where the file is located on someone’s hard drive. Additionally, formal policies can be given context by being placed next to guidelines, best practices or a bit of history. In addition to wikis, policies and guidelines can also be shared using a social, document-sharing site like Scribd. This is a site where documents, images and other files can be uploaded and described. The files can easily be embedded in other sites or just linked up. Scribd preserves the actual document as it was formatted. Viewers can comment on files or share them.

This is similar to Slideshare, which hosts slides in PowerPoint, PDF and similar slide formats. Slideshare can be a nice option for spreading the word through images and text. The progression of slides can be an effective way to build an argument for staff members or members of the public who do not have time to sit and read newsletters or emails. Both Scribd and Slideshare allow others to embed outside information in their sites.

Collaboration

As mentioned in Chapter 3, social media can bring staff members together to get work done. Collaboration can go beyond emailing documents toward a more efficient effort. As mentioned above, staff wikis allow for the sharing of ideas and information. This could be meeting notes summaries and “to do” lists. Facebook provides private group pages that can be accessed only by designated individuals. With Facebook’s browser version on desktops and app version on mobile devices, this can be an easy to use way to share notes and update individuals on the progress of projects. A social site like Ning can also allow staff members to share ideas and schedule events easily.

As mentioned in Chapter 3, social media can bring staff members together to get work done. Collaboration can go beyond emailing documents toward a more efficient effort. As mentioned above, staff wikis allow for the sharing of ideas and information. This could be meeting notes summaries and “to do” lists. Facebook provides private group pages that can be accessed only by designated individuals. With Facebook’s browser version on desktops and app version on mobile devices, this can be an easy to use way to share notes and update individuals on the progress of projects. A social site like Ning can also allow staff members to share ideas and schedule events easily.

Our library has maintained a staff forum blog as a way to share information between our library staff members. This works as a makeshift staff newsletter. It is password protected so that it is not open for the whole world to read. The advantage of the blog for us is that it is easy to identify new information as new posts appear at the top. We can set up email alerts so that staff members are alerted to new posts. The blog is searchable so posts can be found more easily than if they were just email announcements. Additionally, other staff members can leave comments and help to contribute to ideas. The staff forum blog is not direct collaboration between staff members. However, it is an avenue to share information easily so that innovations and changes in the environment can be quickly disseminated. It is an important step toward creating an innovative environment.

As will be discussed in Chapter 5, coordination relies on communication. Individuals must be able to access sites and make decisions about what work needs to be done. They must then be able to submit their work for the benefit of others. Communication is the lifeblood of collaboration. Creating an infrastructure for communication is a first step toward enabling cultural change in the organization. As we will see, creating the infrastructure does not necessarily change the culture. But without the infrastructure, change will be slowed.

Decision making

In 2004, James Surowiecki seduced armchair organizational theorists with The Wisdom of Crowds, where he demonstrated ways that groups of people can make better decisions than any individual in that group. He emphasized the value of prediction markets, which operate like stock markets and are used to predict the outcomes to questions. The leading example of a functioning prediction market is InTrade, where individuals can use actual money to purchase stocks related to real-world events. Political observers often visit InTrade to check the predicted outcomes of elections. Another prediction market is the Hollywood Stock Exchange (www.hsx.com), where users help to predict the success of a film from its inception through its eventual release in theaters. Surowiecki’s work outlines the ways that individuals can come together to make decisions. Sadly, although his arguments are persuasive, his approaches (notably the prediction markets) are beyond the reach of most organizations, including most libraries. Some online polling is the best that most libraries can offer.

Weinberger’s (2012) approach to decision making moves toward more practical application. In the title of his 2012 book, he tells us that information on almost any topic is Too Big to Know for any individual. There are—and always have been—too many pieces of information on almost all topics. The torrent of information on the web has made this more than apparent. A searcher can find information to support and refute any opinion or proposition. This is one of the reasons that Weinberger argues that the top-down, pyramid structure of most organizations is giving way to a networked decision-making structure. In a pyramid structure, knowledge is necessarily reduced as it moves up through the layers of management. There is too much information on any one topic to communicate all of it to leaders. Each level of management reduces details until the decision-maker at the top is left with abstractions and guesses. If middle managers edit out useful solutions, then the top of the pyramid cannot select them. Additionally, individuals across the organization have difficulties in communicating because communication occurs up and down the organizational chart and not across. Innovations must travel up the pyramid; the leaders at the top must recognize how innovations may meet the needs of those below them, and act to implement the innovation. Innovations must flow up and then back down.

Weinberger assumes that no single individual can know enough, so leaders must rely on their networks, including their networked organizations. Knowledge is embodied by a network. Leadership becomes a process where people with useful knowledge come forward at the right time. The knowledge is matched with the situation. Leadership is less about the leader and more about the group being led. The group must be able to store and communicate information in order to make decisions.

This view of decision making matches a loosely-coupled system very well. In loose systems, like libraries, knowledge exists in pockets and leaders can draw on these pockets strategically. To make this happen, people within the network must be aware of problems in need of solutions, and leaders must be able to receive messages about potential solutions. Mechanisms for communication must be in place and organizational members must participate. This is an ideal role for social media because they can create a decentralized, two-way environment that does not sacrifice details and on-the-ground needs of departments. Social media also enable communication across organizational structures. This is related to the idea of capturing internal knowledge discussed in the section above, but the focus here is on how decision makers at all levels of the organization think about using knowledge to enact change.

Part of this decision-making potential arises out of the ability of decision makers to gain a broader view of the organization via social media. If leaders engage in social media to hold an ongoing dialog with organizational members, then they can gain broader perspectives. Online forums such as Ning, Google/Yahoo groups, private Facebook group pages, passworded wikis or blogs can be places where leaders can post ideas and ask organizational members to comment. Naturally, the environment and organizational culture must be utilized to encourage openness and sharing. Managers may be able to learn about activities within the organization via blog posts, tweets and Facebook updates.

The primary way that most employees learn about the organization is through word-of-mouth chatter. The primary technological avenue is through broad email blasts to multiple staff members. Neither of these methods allow leaders to capture and organize communications. Gossip channels are inaccurate and inefficient. Email blasts can be very efficient as a one-to-many stream of information, but they are an inefficient and wasteful mechanism for many-to- many. Social media offer mechanisms that can enable more efficient online group sharing.

Decision making in a social media enriched environment does not mean that everyone gets to make the decision or that that organizations must employ some complicated voting system. It primarily means that open communication channels exist, as does the ability for organizational members to offer solutions. It also means that managers can reorient the attention of the organization more efficiently. Managers and leaders can utilize social media to highlight problems and direct attention. They can also highlight and share successes. Management and leadership are a process of focusing attention and enabling action. Social media can be the infrastructure to make this happen.

Visibility

It may seem obvious that one outcome of social media is to increase a library’s visibility, but it may be less obvious that visibility can bring about more visibility. When I was a new librarian, I convinced our director that we should be holding public events. This is something that our academic library had not really done in a serious way. After some discussion, she said yes, and we moved forward. We had some early bumps along the way. We needed to move around furniture, work with our campus multimedia services to set up a sound system, and then convince faculty members to speak in the middle of an open, active library. Our first events were poorly attended. But over time, we learned from our mistakes, reorganized our space, installed a sound system, and started podcasting events. At first, I spent several years begging faculty members to participate, but as we held more events, awareness grew. Event planners around campus recognized the advantage of being in an active space and having events distributed as a podcast. Over time, event organizers increasingly sought out the library as event space, and today, we organize a few of our own programs, but mostly events come to us (Figure 4.3).

The more visible a library is, the more visible it will become. This isn’t just true with public events and podcasting. Social media tools have a multiplier effect. As more people connect with a library, the more likely they are to share posts by its staff and the more likely they are to help increase the awareness around the library’s content. A library’s network does the work for it. But visibility extends itself beyond the virtual space. The online connects to the physical. As discussed earlier, the virtual extends itself into the physical in terms of marketing, user-generated content, and even jumping into important conversation. These are ways to extend visibility. We can target our actions to purposefully connect the physical and virtual. When we write online about local events and groups, we can encourage them to share what we have written. When we meet community leaders, we can even ask them to connect with us and with the library online. Naturally, the larger goal is that social media can help us demonstrate that our library is more than just a library—it is people too.

The more visible a library is, the more visible it will become. This isn’t just true with public events and podcasting. Social media tools have a multiplier effect. As more people connect with a library, the more likely they are to share posts by its staff and the more likely they are to help increase the awareness around the library’s content. A library’s network does the work for it. But visibility extends itself beyond the virtual space. The online connects to the physical. As discussed earlier, the virtual extends itself into the physical in terms of marketing, user-generated content, and even jumping into important conversation. These are ways to extend visibility. We can target our actions to purposefully connect the physical and virtual. When we write online about local events and groups, we can encourage them to share what we have written. When we meet community leaders, we can even ask them to connect with us and with the library online. Naturally, the larger goal is that social media can help us demonstrate that our library is more than just a library—it is people too.

Finding a focus

Single social media tools such as Facebook, Twitter and blogs can serve many purposes unto themselves. This chapter has outlined options and presented a challenge around how tools work best with our goals. Managers and leaders face the difficult task of selecting a focus and encouraging participation. In loosely-coupled systems, allowing looseness around technologies can be an advantage. This allows experimentation. Managers do not need to understand exactly how a technology should be implemented at the outset. Organizational members can try out options and provide feedback. But managers must also be aware that most staff members work to avoid conflict. If they have a good head on their shoulders, they are cautious by nature. They keep an eye out for organizational landmines. As discussed in Chapter 2, organizational members also rely on a degree of predictability in their jobs. They rely on organizational control mechanisms to give them an outline of how the organization operates. Therefore, organizational members have a need for focus and context around new technology tools.

Managers should ensure a degree of looseness around tools, but they also must recognize that providing some definition around how technologies can be used will push innovation further down Naisbitt’s phases of development. When new technologies arrive, people often understand new tools based on past technologies. This is why we have repurposed paper terminology for the online world in web pages, folders and desktops. In another example, the word blog is a simplification of web log. A log of course refers to a systematic recording tool, which dates back to the wooden floats used by ships on long voyages. We understand technologies based on what we know. We use technology to accomplish tasks that we already do, and we evolve new ways of thinking around the technology.

Chapter 5 examines how we can rethink organizational structures to enable adaptation and innovation around social media. But before this can happen, managers and leaders must consider the range of purposes that are possible. As library staff members have experimented with social media, they have undoubtedly uncovered many possibilities. Organizational staff members have experimented and dabbled with social media in their personal lives. Even if they are not information producers, most of them are social media consumers. Therefore, knowledge and experience already exist in the organization.

As discussed at the outset of this chapter, one question for managers and leaders to consider is the level of individualized service that a library will provide via social networking. Does each librarian, each department, or just the library as a whole have a Facebook page, blog or Twitter account? These are questions that members of the organization can help answer. Managers can employ a process to define a purpose and direction for action.

A first step is to identify what social media tools have been used within the organization. Managers and leaders probably have an awareness of some of the tools, but a more formal survey may be necessary to ensure that all tools are uncovered. The survey can try to differentiate between tools that are used professionally and personally. If the survey results show that staff members’ knowledge of social media tools needs some enhancement, the library may want to consider following one of the versions of the “23 Things” discussions—a learning 2.0 program designed by Helene Blowers, Technology Director of the Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, that has spread to libraries around the world. The 23 Things discussion is a great way to foster change in a library.

When managers highlight successful uses of specific technologies, they are sending the signal that this is something for others to replicate. Managers can send signals through awards, recognitions, mentions at meetings or write-ups in newsletters. There are many times when highlighting the technology is enough of an endorsement that others feel empowered to experiment. All the focus that is needed is a pat on the back. Of course, there will be times that more formal guidelines or policies need to be written. This may draw from a purpose or mission statement created for social media efforts. A purpose statement needs to address the two questions introduced way back in Chapter 1: how will a particular tool be useful for me and what information will I choose to share?

When trying to define a purpose, managers should try to aggregate the views of a broad number of staff members. Getting people to think independently is important so that each person is not overly influenced by the most vocal or those further up the organizational chart. This can be done through a basic visioning exercise where staff members picture a perfect world. In the ideal world, how can social media address the needs of our users? Ask people to write out their views. Then, ask them to write out key ideas and post them on a wall or white board in a meeting room. Ask them to organize them as they post them. Organize ideas into tools, uses, goals, populations or any other categories that make sense. This exercise can be done in an afternoon as a group or over weeks individually. After participants have contributed, the exercise organizer can summarize the ideas and write them up into a workable document for comment and additional review. This is an iterative process where ideas are contributed and refined. This is most useful when the organization needs a push. The goal of discussions around social media should be not only to produce a statement or some written document, but also to create awareness, knowledge and ultimately action. People in the organization can identify ways that social media can improve services. They recognize a need. Sometimes, they may not know that they know. Managers can start a process to identify needs.

When trying to define a purpose, managers should try to aggregate the views of a broad number of staff members. Getting people to think independently is important so that each person is not overly influenced by the most vocal or those further up the organizational chart. This can be done through a basic visioning exercise where staff members picture a perfect world. In the ideal world, how can social media address the needs of our users? Ask people to write out their views. Then, ask them to write out key ideas and post them on a wall or white board in a meeting room. Ask them to organize them as they post them. Organize ideas into tools, uses, goals, populations or any other categories that make sense. This exercise can be done in an afternoon as a group or over weeks individually. After participants have contributed, the exercise organizer can summarize the ideas and write them up into a workable document for comment and additional review. This is an iterative process where ideas are contributed and refined. This is most useful when the organization needs a push. The goal of discussions around social media should be not only to produce a statement or some written document, but also to create awareness, knowledge and ultimately action. People in the organization can identify ways that social media can improve services. They recognize a need. Sometimes, they may not know that they know. Managers can start a process to identify needs.

Start a good blog

Libraries that have not dabbled in social media may wonder where they should start. The answer may sound straight out of 2004, but it remains true: start a good blog. Blogs remain the most flexible social media tool. They allow for article- length posts, short posts, uploaded photos, embedded video and links to other pages. As discussed in Chapter 6, RSS can be used to redirect blog content to standard websites, social networking sites and mobile devices.

Additionally, blogs have low technological barriers. Anyone who can sign up for a free email account on Yahoo or Gmail can create a blog. Multiple staff members can post content, and they can use categories to add a layer of organization and searchability. For libraries that cannot afford full-blown content management systems, blogs can fill the role. The smallest library, tucked away in the most out-of-the-way hamlet can start a blog for free. Blogger and Wordpress remain the leading free, web-based blog platforms. Their broad user communities enable a great deal of online support.

Challenges of participation

Libraries face a few challenges in utilizing the social media world. Several revolve around encouraging our organizations to coordinate their work effectively, which is the focus of Chapter 5. But one challenge comes from users. Specifically, most do not access social media because they want to connect with libraries. Research shows that most users join tools like Facebook and Google + in order to connect to people they already know (Smith, 2011). Most library Facebook pages have zero interactions from users (Gerolimos, 2011). Individual libraries will not be able to change these user habits overnight, but these habits can change. A decade ago, users would have never thought to email libraries or chat online with librarians, but today such interactions are commonplace. My library receives more emails, chats and texts from users than we do phone calls. Connecting via social media can follow this trend. Part of our efforts must focus on changing the expectations of our users.

Users expect us to be what we’ve always been: storehouses for information. Obviously, this is a role we do and should and continue to play. However, we should also continue to play our other role, which is a center of community. Our services are evolving within an ever-changing information world. As we consider how we can utilize social media, we must keep our larger goals in mind. The focus of social media must move our larger goals forward and make us more vital to the communities we serve.

Often, libraries have had standardized services limited by space, resources and our inability to reach beyond our library walls. Social media can help us break out of our own fast food tendencies. For decades, we have expected users to adjust to us, navigating our call number and subject headings. Part of our challenge was in our inability to reach out and connect. While we may not always be able to transform all of our services, we are now more able to share knowledge and connect to users.