Connecting social media tools to the organization

Abstract:

Managers and leaders can embed social media into the fabric of the organization by using the four coordination tools: policies, budgets, organizational policy and participation rules. However, when these tools are implemented, managers face a conundrum of control: the more controls that are put in place around social media, the less useful the tools become. Nevertheless, managers must still work to coordinate their use as the misuse of social media can damage the larger organization. Policies are the foundation for setting the view of organizational members toward social media; budgets set the foundations for technology and training; organizational culture fills in the gaps; and participation rules define how staff members make decisions. Managers can define structures around social media to give coordination tools form and encourage staff members to participate. Managers and leaders must work to encourage employees to use tools and be ready to give appropriate attention to any complaints around social media.

Introduction

Imagine the staff of a library all sitting together in a large conference room. They are given the following options. If everyone in the room writes down the word “yes” on a piece of paper, then everyone gets a seven-day paid holiday. If even one person writes down “no,” then the people who wrote down “yes” give up seven days out of their yearly holiday schedule. Anyone who writes down “no,” gains and loses nothing. Staff members are not allowed to speak to each other as they decide what to write. If everyone writes “yes,” then everyone benefits. If even one person backs out, those who took the risk suffer.

What would happen if this was actually tried with library staff? More than likely, staff members would look around the room and consider the trustworthiness of the other people sitting near them. They would think to themselves, “do I really think that each one of these people will write yes?” The odds would predict that at least one person would write “no.” They would probably not be willing to take the chance. They would rather walk away without losing what they already had.

Now, imagine the same scenario. But, this time managers allow staff to talk to each other. What would be different? A stronger chance exists that peer pressure can change this outcome. The most vocal staff members could walk around and encourage everyone to write “yes.” It may require answer checks and stern looks, but simple communication can change the outcome. Communication can build trust in the group so that all work together.

This example is a classic coordination problem. Behavioral economists and mathematicians who study game theory specialize in solving these types of problems. The heart of coordination problems is the need to trust and communicate. In the first example, when staff members couldn’t communicate, they struggle to trust each other. They know that at least one person will fail to participate. When communication occurs, it becomes easier for everyone to coordinate their actions.

As discussed in Chapter 2, coordinating action is a central challenge for libraries. As loosely-coupled systems, the service interactions offered by staff members are not directly tied to each other. We work in systems that create new knowledge as they interact with the world, but we often lose that knowledge immediately after it is created. This knowledge may exist in the heads of the people who created it, but in order for the system to benefit from it, the individuals must have sufficient recall to use it again. If other staff members are to benefit from the knowledge, they must know to ask about it. In Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, the ability to capture knowledge and join conversations was presented as an advantage of social media in loose systems. As many staff members will never work together, sharing across our social media infrastructure makes knowledge usable in new situations by multiple individuals.

But, as one can imagine, if staff members choose not to share, then social media provide no benefit for the organization. Social media can be likened to a party. The host can decorate and prepare food and drinks, but if no one shows up, it isn’t a party. If only two people show up, then there will be some awkward conversation and uncomfortable silence. The challenge around effective social media implementation is getting library staff to see social media as an integral part of their jobs so that they choose to participate. If people are fearful of participation or do not see the value, they will not participate.

Decision making in a networked environment relies on the ability to access needed knowledge in context. Networked decision making is enabled by communicating across the organization. In traditional organizational structures, leaders and managers require knowledge to be filtered up the chain of command. Knowledge about the organization comes from observation, written documents and usage data, all of which can be disconnected from the actual interactions and services provided by the library. The challenge with traditional organizational structures is that they put pressure on managers to actually manage the structure and build mechanisms for data sharing. It is up to managers to share knowledge and connect individuals to each other. Social media can ease the pressure on managers to catch and aggregate all knowledge. Coordination thrives in environments where communication occurs easily and freely.

Not too long ago, before everyone had cell phones in their pockets, meeting friends at the local shopping mall required work to be sure you arrived at the same spot at the same time as your friends. Phone conversations were geographically bound from home to home. Once someone left his or her home, that person could not be reached unless he or she found a pay phone and tried to call home. If you were going to meet a friend or family member, locations and times for meeting needed to be set in advance. Today, coordinating trips with friends is much easier. As long as the parties involved select the same day or afternoon, they just need to make a quick call to find each other. We do not need to select a meeting point prior to arrival.

When members of the organization can coordinate their actions, there is less pressure on managers to predict the future because they can share problems more easily and access the knowledge of organizational members more easily. For this to work, managers and leaders must connect goals to the coordination tools—policies, budgets, organizational culture and participation rules—that turn a group of individuals into a functional organization. Yet, managers face a conundrum because the tools that help to coordinate individuals can also be the tools that limit the usefulness of social media.

Conundrum of control

The advantage of the loosely-coupled nature of libraries is their ability to create decentralized knowledge and share it across the organization. Departments and individuals can act as pockets of innovation, driving change across the organization simply by creating solutions for their own localized problems. This occurs when the localized solutions are shared and adapted across departments. In order for this to work, staff members must be able to experiment with new technologies freely. For example, a technical services department may want to examine its workflow in an effort to improve efficiency. The staff may decide to use Tumblr to document each step in their acquisitions and cataloging process. Other departments within the library may find this to be very useful, and library users may find this fascinating as it may give a face to an otherwise faceless process. The use of Tumblr as a documentation tool could become a novel idea within the organization and may lead to similar uses by other departments. In order for this to happen, the technical services staff members must know about and understand Tumblr, but they also must feel that this is an appropriate use of technology within the organization. If staff members were required to go through a lengthy approval process for a new blog on Tumblr, they may decide it is not worth the trouble, and potential innovations may be squashed before they have been tried out.

Individuals are more likely to discover innovations in open environments where they are free to play around with tools. Adaptability—literally the ability to adapt—increases in looser systems where coordination tools like policies, budgets, participation rules and organization culture do not hamper experimentation. As discussed in Chapter 2, coordination tools create a framework within which the organization exists by allowing individuals to come together, divide labor and get work done. But coordination tools also provide a degree of protection for organization members and for the organization itself. These tools define what is allowable and what is not. Often, formal policies define “right” and “wrong,” and organizational culture fills in the gaps. So, if the technical services department wants to use Tumblr to document its cataloging process, the library’s coordination tools will define whether or not this is permissible. Should the cataloging process be communicated outward to the public? Only the values and beliefs of a particular library can answer that question. In my own library, that would be no problem, but in other places, it may be frowned upon.

Thus, library managers and leaders face what Harvard University’s David Weinberger (2007) calls a conundrum of control. This conundrum states that organizations need to utilize coordination tools in an effort to give form and offer control of tasks, messages and the actions of employees. But the more controls that are in place around social media, the less useful the tools become. The point of coordination tools is to provide definition, but definition is applied around technological applications that are already known. This means that new applications must be excluded or organizational members must seek approval for new applications, which can be cumbersome.

For example, a librarian may want to live blog a panel discussion that will be held in the library. Live blogging the event will allow real-time notes to be sent out as the event happens, but maybe no one has ever live blogged an event in the library. Maybe the library’s blog has just been used for announcements and book reviews. What should the librarian do? The librarian could seek approval from supervisors, which may take meetings and documentation. The supervisor may need to take this idea to his or her supervisor. Managers may require a written description of live blogging, which may need to be included in the technology policy so that it is clear that this use is permissible. There is a point where the librarian will decide that the work to get this approved is not worth the effort. In smaller libraries, the layers of red tape may be easier to navigate, but the interpersonal dynamics may be just as cumbersome. If the library’s blog has only been used for book reviews and news updates, then other staff members may think that live blogging an event is not an appropriate use of the technology. Even if there are fewer layers within the organization, staff members may disagree about what is appropriate and what is not. This may lead to informal, backroom bickering that is not productive. Again, the librarian who is interested in using the blog in a new way may ultimately decide that it is not worth the effort.

As we can see, overly controlled environments can dampen innovation, so pulling back controls may be useful. But a lack of control also presents risks to the larger organization. Anyone who has spent any time online knows that there is a dark side to social media, and the web in general. Rude comments on blog posts are not unusual. Edited photos of celebrities, politicians and others are so regular that when one sees a strange photo, the first question asked is whether it has been Photoshopped. Viewers no longer trust what the eyes see. The global, open forum provided by the web and the ease of use and immediacy provided by social media present risks for organizations and individuals. Many times these risks do not focus on overtly rude and inappropriate comments or images. Often, they revolve around private or personal comments that enter the workplace.

For example, in 2010, a sociology faculty member named Gloria Gadsden was removed from campus at East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania after joking on Facebook about killing students (Miller, 2010). It is unlikely that university administrators thought that Ms Gadsden would actually take action against students, but following violence on other campuses, administrators probably felt compelled to act once students brought this to their attention. The college administration could not appear to ignore a potential threat.

Similarly, Kimberley Swann a 16-year-old receptionist at Ivell Marketing and Logistics Limited in Clacton, UK was fired for posting on Facebook that her job was boring (Sky News, 2009). This may feel like overreaction by managers, but it highlights the disconnect between what employees and management may consider appropriate.

A more high-profile suspension was that of US news anchor and syndicated columnist Roland Martin who was suspended by news network CNN following a tweet he made during the US Super Bowl. He wrote, “If a dude at your Super Bowl party is hyped about David Beckham’s H&M underwear ad, smack the ish out of him! #superbowl.” Complaints calling this tweet insensitive and promoting violence started rolling in to CNN almost immediately. CNN could not afford to look as if they supported Martin’s statements, so they took action. Martin offered an apology (Carr, 2012).

Organizations also face concerns over the release of information that may damage operations. In the days before social media, the distribution of internal or proprietary information was not so easy. Today, a click can send it worldwide. A prime example occurred in 2010 when the Israeli Defense Forces had to call off an operation because a soldier revealed the mission’s location, day and time (Waghorn, 2010).

Managers may also face difficulties in controlling messages about their organization. The Obama administration learned this in the spring of 2011 following a raid by US special forces troops on a compound in Pakistan that housed terrorist leader Osama Bin Laden. This raid resulted in Bin Laden’s death and the end of a nearly decade-long manhunt. Following Bin Laden’s death, President Barack Obama prepared to address the world, but the news had already been leaked. It was leaked by a government bureaucrat name Keith Urbahn who tweeted, “So I’m told by a reputable person they have killed Osama Bin Laden. Hot damn” (Pasetsky, 2011). By the time President Obama gave his speech, the media were already in a frenzy over the news.

Media agencies have also needed to address the role of social media in reporting. For instance, the BBC has instructed its reporters and producers that news should be broken through the newsroom and not through Twitter. The BBC recognized that tweets during an ongoing event, such as a trial, may be very valuable as part of their coverage, but when a major event happens, like the verdict of the trial, that event should be sent through the BBC’s standard coverage first and not through Twitter (Plunkett, 2012).

These examples highlight just some of the challenges faced by organizations. Bogdan Dumitru (2009) created a list of social media risks to corporations, which is adapted here for libraries:

![]() Organizational reputation: Staff represent the library in global communication, so the ways that they interact reflect back on the library for good or ill. Misstatements on controversial issues, insensitivity to people and populations, indelicate interjections into religious discussions, and oversteps in political debates can pull a library into unneeded distraction and controversy.

Organizational reputation: Staff represent the library in global communication, so the ways that they interact reflect back on the library for good or ill. Misstatements on controversial issues, insensitivity to people and populations, indelicate interjections into religious discussions, and oversteps in political debates can pull a library into unneeded distraction and controversy.

![]() Involuntary information leakage: Library staff can also make accidental missteps by letting out information that for legal or strategic reasons should be kept out of the public eye. Posts or comments around HR decisions or the hiring process should be kept out of social media. Libraries that are governed by boards of trustees or other municipal structures need to take care what and how they post about decisions that need to be made within the governing structure.

Involuntary information leakage: Library staff can also make accidental missteps by letting out information that for legal or strategic reasons should be kept out of the public eye. Posts or comments around HR decisions or the hiring process should be kept out of social media. Libraries that are governed by boards of trustees or other municipal structures need to take care what and how they post about decisions that need to be made within the governing structure.

![]() Intellectual property risks: A great deal of the content on social media sites revolves around use of other people’s intellectual property. This may involve posting quotes, book covers, images and music. Fair use guidelines can be blurry. Libraries need to support authors, artists and creators of information, and we can do this by helping to highlight their work. However, we also need to be careful we are following these guidelines. This includes ensuring that appropriate procedures are in place to handle images and recordings from events held in the library.

Intellectual property risks: A great deal of the content on social media sites revolves around use of other people’s intellectual property. This may involve posting quotes, book covers, images and music. Fair use guidelines can be blurry. Libraries need to support authors, artists and creators of information, and we can do this by helping to highlight their work. However, we also need to be careful we are following these guidelines. This includes ensuring that appropriate procedures are in place to handle images and recordings from events held in the library.

![]() Data theft: While libraries do not handle as much highly sensitive information as a bank, libraries do need to be aware of the realities of identity theft and be careful with patron information. Most library integrated systems have names, addresses, reading habits and other personal information about library users. This information may not be directly connected to social networking tools, but managers should be aware of who has access to this information and how easily it could be shared.

Data theft: While libraries do not handle as much highly sensitive information as a bank, libraries do need to be aware of the realities of identity theft and be careful with patron information. Most library integrated systems have names, addresses, reading habits and other personal information about library users. This information may not be directly connected to social networking tools, but managers should be aware of who has access to this information and how easily it could be shared.

![]() Spam, phishing, malware and network vulnerability: Any time a library’s network accesses the rest of the internet there is a degree of risk from malicious software and individuals. Social media can be a delivery mechanism for malware and also for apps that collect user data. Most of these risks are manageable and generally minor, but managers should have an awareness of such risks.

Spam, phishing, malware and network vulnerability: Any time a library’s network accesses the rest of the internet there is a degree of risk from malicious software and individuals. Social media can be a delivery mechanism for malware and also for apps that collect user data. Most of these risks are manageable and generally minor, but managers should have an awareness of such risks.

![]() Maintenance costs and productivity loss: There is a cost in staff time related to social media. Most of the time it may be worth it, but it is a cost none the less. For social tools to be useful, they must have a regular flow of information, which takes time commitment. Additionally, staff may get pulled into their own personal social media accounts and spend “on-the-clock” time on their own accounts.

Maintenance costs and productivity loss: There is a cost in staff time related to social media. Most of the time it may be worth it, but it is a cost none the less. For social tools to be useful, they must have a regular flow of information, which takes time commitment. Additionally, staff may get pulled into their own personal social media accounts and spend “on-the-clock” time on their own accounts.

Librarians and staff members can easily and cheaply communicate globally, but a tweet or post does not need to go global to cause problems for organizations. Several of the above risks can be solved with updated anti-virus software, a decent firewall and IT staff that keep up with the demands of operating a local network. But several of the risks—namely organizational reputation, involuntary information leakage, intellectual property risks, maintenance costs and productivity loss—are softer risks that cannot be solved through technology. As discussed in Chapter 1, these are the people problems that require more graceful solutions and ongoing management.

When faced with these risks, managers and leaders face the temptation of being heavy handed and stamping out innovation. The simplest way to control problems is to set limits. Generally, limits take the form of rules that either prevent access so that only specific people can use technologies or reduce functionality so that technology can be used only in predefined ways. Another common solution is to establish punishments for misuse. This becomes a limit-by-fear approach. Instead of offering guidance, managers create an environment where it is easier to avoid the technology than risk punishment for misuse. The result of these limits is that technologies become less useful and less adaptable.

The conundrum of control faced by managers is that the use of social media tools requires some kind of form and context. But the more structures that are put in place around these tools, the more people and energy are required to manage them. There is a friction cost. The life of a social media tool cannot be planned. It cannot be managed. If it is to meet changing needs, it needs to grow and adapt along with the needs. However, social media tools can be coordinated and given context. Staff members need to be able to make sense around tools so that they feel comfortable innovating and rethinking how technology applies to the organization.

Managers and leaders must recognize that a healthy tension exists between focus and innovation. Reaching organizational goals requires planning, which requires some degree of focus. Budgets and actions must align in order to move forward. Focus is required to keep staff members from moving in a thousand different directions at the same time. Organizational members cannot reach a goal if they cannot see the goal. Nevertheless, innovation often requires us to blur this focus. Organizational members may need to move away from one goal in order to invent a new goal. The rebellious voice that is willing to point out a problem and offer a solution is the voice that makes change happen. The process of refocusing can be slow and painful. Managers must live within this tension or innovation will never really be realized.

Success for social media is tied to the willingness of organizational members to participate. Managers can require them to write blog posts, but any post that is compulsory will be safe, neutered and meaningless. The most powerful use of social media is by engaged staff members who see an opportunity to make a difference. Managers cannot force people to want to make a difference. The best option is to create an environment where people feel supported and want to make a difference.

Coordination tools and social media

Chapter 2 outlined the library as a loosely-coupled system and how the coordination tools of budgets, policies, participation rules and organizational culture allow individuals to come together and accomplish work. Coordination tools allow organizational members to make sense of their place within the larger whole. Knowledge about the organization is filtered through the prism of coordination tools. Did the organization reach its goals? What are the most significant obstacles to success? Is this a good place to work? What technology is useful? Who fixes problems? Who causes problems? Who is allowed to speak up about problems? These are all questions that coordination tools help answer.

Coordination tools can be utilized to create an environment where cooperation, collaboration and engaged use of the technology can thrive. Naturally, this is often easier said than done. Managers and leaders must work within the organization they find. Pushing a closed organization toward openness before it is ready is a recipe for disaster. It is akin to a body rejecting a transplanted organ. Organizational members who are accustomed to living in an environment where openness results in negative consequences will be scared to death of sudden openness. Movement toward change needs to fit the particular library’s culture and follow a trajectory that makes sense. Managers and leaders must recognize where their organization stands and move forward appropriately. Examining the organization’s coordination tools can be a way to initiate change.

Policies and engagement

Policies are often the coordination tool that comes to mind first when we consider the operation of organizations. When questions arise, organization members ask, “what does the policy say?” In many situations, individuals desire clarity, and that is exactly what policies appear to give. As new initiatives are put in place, managers and leaders often write policies, which can feel like accomplishment. The written word, capturing ideas, presenting the rules to make change a reality. Of course, anyone who has worked in an organization knows the truth, which is that policies are rarely consulted. They are often forgotten almost as quickly as they are written. Practices change over time, new technologies arise, and policies become separated from reality.

The problem is that leaders and managers often expect policies to do the work of people. They expect policies to remind people of the proper approach to technology and to help clarify ambiguous situations, when these responsibilities should really fall to managers. Policies, as written documents, are never good at reminding anybody of anything, and they rarely offer guidance through ambiguity.

This is not to say that policies are unimportant. The most important purpose for any policy is during the implementation stage of a new service or technology. This is when policies have the most potential to drive change. The creation of the policy itself is a vital step in fostering change. Policies should not just arise from the minds of leaders like Athena from the head of Zeus. The process in writing the policy can initiate change. A policy written in secret and dumped on organizational members will be ignored or will cause a revolution. It does not foster healthy change.

The process around creating policies will depend greatly on the size of the organization. Organizational leaders will be in the best position to define the needed process. No matter the process, a first step to creating a useful social media policy is to get the right people at the table. Assign this task to the people who are most involved and most knowledgeable. The makeup of this group will vary widely from organization to organization. This group must spend time gathering input from people not at the table. The writers also need to understand the needs of staff and library users. In addition to understanding needs, the process of reaching out to staff members starts to build awareness that change is coming. After the writers have started to gather input, they should review existing policies to discover gaps and to consider whether existing policies should be rewritten. Writing by committee can be painful. Sometimes multiple authors must write together, and other times, a single author can be assigned the task. But ideas must reach a computer screen somehow. After the writers have created a draft policy, this should be shared within the organization in order to get feedback and catch any potential problems. After this input has been incorporated, the policy can be sent up for approval from the director or governing board as appropriate.

Larger organizations have the potential to be constantly editing and rewriting policy documents. Creating a highly involved process covering many organizational members may not be possible, because too much time and energy will be spent writing policies. In contrast, smaller organizations may not have the people to devote to a highly involved writing process. This may fall to one or two people. Managers will need to weigh the impact of a policy and level of energy involved with writing the policy. As social media have low barriers to entry and therefore could be utilized by all members of the organization, a more involved and high- profile process may be warranted. The more attention given to the process, the greater the impact the policy will have.

Once the policy has been finalized, the policy should become a tool for fostering conversation and change. The policy should be sent around and promoted to turn attention to the change it represents. Managers should highlight new features emphasized by the policy and use this discussion as a way to move change forward. The initial creation and implementation of the policy offers the widest splash and most significant instance for shifting an organization.

Once in place, policies are most powerful when in the hands of a manager or leader. When members of a department are experimenting with a new tool, managers can hand them the policy, point out ways to avoid pitfalls, and emphasize the benefits that social media can bring to the organization. The ongoing relevance of any policy is really in the hands of managers and leaders. It is up to them to keep the approach and values defined in a policy at the forefront of the day-to-day activities of the organization.

Most libraries already have some sort of technology-related policy. A wave of policies were put in place in the late 1990s and early 2000s focusing on email, internet use and chat rooms, all of which were cutting-edge at the time. As social media tools have grown and evolved, many organizations have not devoted energy to updating existing policies. Keeping policies updated takes energy and time that most libraries do not have, especially considering that policies are often put away and forgotten. One may ask, “why update policies?” Updating policies can be useful for several reasons.

First, a significant policy revision is the first step to increasing the use of new technologies. In fact, the most important purpose for policy documents is to promote use. Even though social media may be relatively inexpensive, most libraries have already invested in computers, network access and the time of their staff. Managers and leaders should want these resources used to advance our missions as much as possible, and social media can definitely add value. Too often, staff members view policies as lists of rules defining inappropriate actions. Policies should actually be the opposite. Policies should enable action by defining how tools can be useful and how they will help to accomplish organizational goals.

Second, a policy revision can help organizational members clarify organizational values. Policies are essentially codified value statements. Policies connect values to actions. When managers use policies to threaten staff members with consequences for breaking a list of rules, they communicate values. They indicate that the organization will not support innovation. When policies define an environment for success, they communicate a desire for continuous improvement.

Third, a policy revision can educate staff members about legal concerns. Even though most policies overly focus on legal issues, legalities still remain important. Different laws will come into play depending on the type of library. A librarian or staff member at a university library with a focus on the curriculum may relate to users differently than a public library that may technically be part of local government. The concerns of a children’s librarian may differ from those of an adult services librarian. The country, region, type of library and user community will greatly influence the legalities around social media. No matter the legal requirements, policy writers should take great care in crafting the legal wording. This is the type of language that can easily scare staff members and discourage use. Whenever possible, writers should try to offer examples and guidance to help staff members avoid falling into legal problems.

Finally, a policy revision can define or redefine responsibilities. Are social media organized at the department level or is there a single social media presence for the entire library? Are social media the responsibilities of individual staff members? Who can approve new social media tools? Most organizations have already answered these questions through exploration of the tools, but the answers may not be reflected in policy. Writers must be careful not to go too far with defining workflows in policy documents. Policies can be difficult to change, and workflows often need to be flexible.

Staff members will initially think about social media policy in relation to policies they already know or to policies that they think they know. The most prominent in most organizations are policies relating to email, which is a tool used many times each day. The degree of regulation, acceptable personal use, and degree of support around email will affect the ways that individuals see social media. As social media tools evolve, newer tools (such as Pinterest or Tumblr) will be viewed from the framework of older tools (like blogs or Facebook). The ways that managers and organizational members rely on these tools to accomplish goals will set the tone for the adoption of new tools. A policy revision can help to solidify these approaches if they are healthy or can help to change them if they are not desirable. In any case, staff members will connect existing policies and existing technologies to new technologies.

Crafting a Social Media Policy

Many templates for social media policies exist. It can be useful to review policies of peer libraries if possible. Almost all social media policies will include a purpose statement or statement of goals. This statement should be purposefully broad and must promote use of the technology. The first sentences of the policy are the sentences most likely to be read by staff members. For example:

Social media sites such as blogs, wikis, Facebook and Twitter are important tools in advancing our library’s mission by allowing librarians and staff members to easily offer services to library users. Our library views the active use of social media as being vital to our success in the future through improving the educational needs of library users and improving communication between librarians and staff members within the library.

A purpose statement may want to connect social media back to other established practices:

The ethic of customer service and friendliness that is at the heart of our face-to-face interactions should guide our application of social media.

To clearly outline the benefits that social media can provide, a benefits statement can be included as part of the purpose or can be included as a separate section of the policy:

Social media provide the following benefits to our library:

![]() two-way communication between librarians and library users;

two-way communication between librarians and library users;

![]() easy communication of library services and programming to the community;

easy communication of library services and programming to the community;

![]() online learning space where individuals can share information;

online learning space where individuals can share information;

![]() opportunities to support the library’s existing online research databases.

opportunities to support the library’s existing online research databases.

The list of benefits will vary depending on the library and the approach to social media. The benefits statement is an opportunity to highlight the potential for social media and give innovation a push forward. A policy may need to define “social media” just to be clear about the types of sites to which the policy applies:

Social media refers to websites or smart phone apps that allow for the immediate publication of information on the internet and for immediate user comment. Often social media sites allow users to share postings, links, images or other information between staff members and the general public. This may include social networking sites such as Facebook or LinkedIn, blog sites such as Blogger or Wordpress, micro-blogging sites such as Twitter, or video sharing sites such as YouTube.

The level of necessary definition will depend on the organization. If the goal is to encourage use from less savvy users, including detailed definitions may be appropriate.

Following definitions, a policy statement may need to outline use guidelines. If done incorrectly, these will read like a list of edicts not to be violated. If done correctly, these can create a framework around the use of social media. For example:

Social media enable our library to improve our community through seamlessly sharing information and promoting our services to library users. The following approaches to social media should guide our use of social media:

![]() The ethic of high-quality customer service that is central to our face-to-face service should guide our online services.

The ethic of high-quality customer service that is central to our face-to-face service should guide our online services.

![]() User privacy is at the heart of our mission. In supporting this mission, we will take great care in sharing information about users and users’ reading habits.

User privacy is at the heart of our mission. In supporting this mission, we will take great care in sharing information about users and users’ reading habits.

![]() As a learning-centered institution, we believe in and support the copyright of authors, musicians, filmmakers and others who create information.

As a learning-centered institution, we believe in and support the copyright of authors, musicians, filmmakers and others who create information.

![]() Any librarian or staff member who recognizes a need that social media can address should work within his or her department to implement the social media tool.

Any librarian or staff member who recognizes a need that social media can address should work within his or her department to implement the social media tool.

![]() Librarians and staff members should not fear difficult topics as long as they are posted for the appropriate audience and introduced in the proper context. For instance, some topics may be appropriate on a page for an adult book group that may not be appropriate for a page designed for teens or children.

Librarians and staff members should not fear difficult topics as long as they are posted for the appropriate audience and introduced in the proper context. For instance, some topics may be appropriate on a page for an adult book group that may not be appropriate for a page designed for teens or children.

![]() Our library encourages librarians and staff members to be consumers of social media to enrich their lives. When using social media for personal or professional activities that are not directly tied to their position in the library, librarians or staff members should indicate that they do not represent the library in postings referring to the library.

Our library encourages librarians and staff members to be consumers of social media to enrich their lives. When using social media for personal or professional activities that are not directly tied to their position in the library, librarians or staff members should indicate that they do not represent the library in postings referring to the library.

![]() Our library seeks to create an open and safe environment for information sharing. User comments on library social media sites that are deemed to be combative, offensive or threatening will be removed by the library staff member responsible for managing the library’s social media presence.

Our library seeks to create an open and safe environment for information sharing. User comments on library social media sites that are deemed to be combative, offensive or threatening will be removed by the library staff member responsible for managing the library’s social media presence.

The list of guidelines can easily become quite lengthy, so writers should take care to include only those guidelines that are deemed absolutely necessary. Lists that are too long and cluttered detract from actually having staff members understand the larger goals of the policy, actually reading the policy, and making a change in actions.

The writers may also include a less formal set of practices than the official guidelines, such as best practices for social media. Best practices tend to be situational and therefore included and excluded as circumstance dictates. A best practices statement may state:

The following list of best practices may be useful to social media users within our library.

![]() Departments within our library may wish to write their own use guidelines for social media tools. This may help librarians and staff members understand how social media can advance the department’s goals.

Departments within our library may wish to write their own use guidelines for social media tools. This may help librarians and staff members understand how social media can advance the department’s goals.

![]() Communication between our staff members is one way we stay effective and provide quality services. Authors and administrators of the library’s social media sites should communicate with supervisors and other department members about any issues of concern or needs that might arise.

Communication between our staff members is one way we stay effective and provide quality services. Authors and administrators of the library’s social media sites should communicate with supervisors and other department members about any issues of concern or needs that might arise.

![]() Librarians and staff members should try to avoid posting to social media when angry. Negative patron interactions or hotly debated issues can charge us up and lead to a strongly written blog post, tweet or Facebook post that we might not have written in a calmer state of mind.

Librarians and staff members should try to avoid posting to social media when angry. Negative patron interactions or hotly debated issues can charge us up and lead to a strongly written blog post, tweet or Facebook post that we might not have written in a calmer state of mind.

![]() Librarians and staff members who are posting their personal opinions on their personal social networking sites can use the following easy approaches to differentiate their views from their view as a library staff members. They can simply say,

Librarians and staff members who are posting their personal opinions on their personal social networking sites can use the following easy approaches to differentiate their views from their view as a library staff members. They can simply say,

– “I work for at the library, but this is my own personal opinion.”

– “I do not speak for my library, but my own personal opinion is…”

![]() Librarians and staff members may share information on controversial topics. When doing this, they may also need to identify their role as within the library. This may be done in “about” statements on individual social media pages. They can do this by saying something like,

Librarians and staff members may share information on controversial topics. When doing this, they may also need to identify their role as within the library. This may be done in “about” statements on individual social media pages. They can do this by saying something like,

![]() Library staff members should ensure that at least one other staff member has access to social media sites used by our library in case the site’s primary author/administrator is not available.

Library staff members should ensure that at least one other staff member has access to social media sites used by our library in case the site’s primary author/administrator is not available.

The library’s social media policy should be differentiated from the procedures used to post information to social media sites. Writers sometimes feel tempted to include procedural information in policy statements. Some recommendations state that a library should have one policy for the public and one for staff. This flies in the face of transparency and sets up confusing situations where staff may misinterpret the public or internal policies. If writers would like to help clarify actions, then they may wish to create a procedure document to clarify actions.

A procedure defines and organizes a process. This can be very important when coordinating and standardizing actions between many people. The long-term impact of written procedures is to prevent change. They capture and cement actions. This can be useful when an activity is complex and has too many steps for an individual to remember or when multiple individuals must work together on the activity. Written procedures can also be useful when activities may have a large degree of variation, and there is a need to unify action to ensure quality. High-impact activities like computer system implementations or management of personal user data may require precise procedures to ensure that information is managed correctly. Procedures will naturally evolve and change over time, so written documents will go out of date and need to be updated.

Procedures around social media can be helpful depending on the actual service provided. In my library, we have written procedures for posting our podcasts, because there are many steps involved including editing the MP3 file, uploading the MP3 file, updating the XML file, posting the XML file to the server, updating the appropriate page on the library’s website, and writing a blog post about the podcast. On top of these steps, there are three different people who post podcasts, so there is a need to ensure all three follow the same steps. Procedures may be useful to identify appropriate subjects to write about on a blog, handling inappropriate comments by users, and even in creating new social media sites that represent the library.

Impact of budgets

Policies and budgets are the most formal of the coordination tools. Budgets are especially formal in publicly supported libraries. Budgets are often public documents that are developed and published at the end of one year, then implemented following strict accounting standards. They are intended to make expenditures transparent to members of the organization and the public.

Interestingly, many social media implementations exist outside of the budget process. Starting a Facebook page, Twitter account or a blog requires no additional costs. Many libraries have technology committees that oversee budget expenditures on software and hardware. Social media implementations often bypass this process because they have no additional costs. They are “free.” Of course, “free” requires staff time, hardware and network infrastructure. Just because there is not a line in the library budget identified as “Facebook” does not mean that there is not a cost to the many Facebook pages created by the library.

Social media avoid centralized management by being outside of the budget process. Sites may pop up all over the place because organizational members can start them with just a computer and internet connection. The lack of centralization may present issues for managers. Generally, erring on the side of innovation and experimentation may be the best practice, but there may be a point where every department, every project or every staff member is creating individual pages. This can get out of hand. This may be especially true in larger libraries with more staff members and a greater number of projects. The more pages that are created, the more likely these pages will go dormant and obscure current goals. Identifying and managing the different social media tools to eliminate unnecessary pages can be a challenge to managers.

One budgetary action that managers can take to support social media is to carve out time for staff to use them. This may come from hiring individuals to implement social media or from releasing staff members from existing work in order to prioritize social media. Providing hardware such as desktop computers, mobile devices or handheld tablets are additional budgetary approaches to improving access to social media.

Organizational culture and participation rules: creating a shared vision

Legal scholar and internet guru Lawrence Lessig (1999) uses the legal term “latent ambiguity” in reference to an unclear legal situation where existing law no longer speaks directly to new circumstances changed by technology or time. For instance, the meanings of freedom of speech or freedom of the press, which are protected in many countries, have had to be reconsidered with the rise of the internet. Past applications of law may present ambiguities for present situations where any citizen can communicate instantly and globally.

Social media tools evolve so quickly that they guarantee ambiguities. In December 2011, Facebook adopted its timeline feature, radically changing its “wall” interface. Before the timeline, a user’s wall contained a summary of recent activity, but activities from previous years were difficult to find. Facebook users knew that past comments, funny photos and political statements were technically available in Facebook, but they were difficult to access. The timeline changed all of this. Instantly, every interaction with Facebook was organized by date. The default setting was to make all content available to each user’s friends. Although users had the option to hide past activities, they had to do this post by post, which was cumbersome. Some individuals who started using Facebook in college back when parents and employers were not able to access the site were mortified to know that previously hidden information was now easily available. Some of these individuals may have worked in libraries and had some inflammatory remarks buried away in their online past when the Facebook timeline was not foreseen.

The hottest social networking site of 2012 was Pinterest (Figure 5.1). This site allows users to share images and sites using a virtual pin-board. It is open, visual and addictive. At the beginning of 2011, the site was not on the radar. By 2012, it was heavily used and enabling sharing on a massive scale. A library’s social media policy could not possibly have addressed Pinterest in 2011. Unless a librarian was about to invent this site (and it was not invented by a librarian), then there would have been no way to write a policy around it.

The Facebook timeline and Pinterest are two examples of changes that had significant impact in the social media world that could not be easily predicted. Countless social media sites exist across the web, and countless more will be invented within a relatively short time. The formal processes behind policies and budgeting cannot respond quickly enough to address these tools directly. The only real option for organizations is to enable organizational members to adapt to new situations and use their own judgment. This is the role of organizational culture around social media. As discussed in Chapter 2, organizational culture fills in the gaps where formal policies and procedures fall short. This is the realm of values, habits, symbols, history and norms. This is also a realm that can be difficult to change.

A policy document that emphasizes use and is promoted widely is a first step toward creating a healthy social media culture. Promoting successes through awards or mentions in the organizational newsletter is another step. When managers highlight a successful social media tool, they are not just giving a pat on the back those who are responsible. They are communicating values to the rest of the organization. They are saying, “this is ok.” Devoting time for training sessions or funding to send staff to workshops are other visible ways to support social media and push the culture.

Punishment is the most serious way to poison a culture, especially punishment around innovation. The staff member who is punished for creating a social media site without permission will always be remembered. Of course, punishments do not just come from managers. They can also come from coworkers. In 2004, when our library implemented its first blogs, I had to beg and beg to get other librarians to use them. One of our senior librarians put up a post that was written entirely in uppercase letters. Several librarians complained about this in the middle of a department meeting. They said that it was poor etiquette and that she should change the post. I was ecstatic that she actually posted, so I tried to deflect their comments. But, the damage was done. I was not able to get that librarian to post to our blogs for several more years.

The participation rules around social media send a message about the role of this technology to the organization. As discussed in Chapter 2, participation rules exist between policy and organizational culture. These are the written and unwritten rules about who gets to do what. Lessig (1999) discusses participation rules in terms of the architecture of the technology. The code that creates the technology hardwires the values of the organization. The code determines who gets access and what they can do online. Architecture is the formalization of participation rules.

For instance, the job classifications of staff members who have access to social media sites communicate the values of the library. If only reference librarians have access to the library’s Facebook page, then this communicates the page’s purpose. If the page is used only to promote cultural events, this would be a different purpose. The individuals who are designated as page administrators on Facebook would also communicate status. This is not to say that all employees must have equal access to all social media sites. However, managers and leaders must be aware that if a particular page is given a particular purpose, they should be listening to staff at all levels for other needs and find ways to address those needs.

Participation rules often define the level of service that a library will provide. Does the library provide a standardized, fast food approach where one size fits all or does it provide an individualized approach where services adapt to the needs of the specific user? Employees who are allowed to act within their judgments are more able to address the specific needs of the user. Employees who feel limited will only offer a standardized service. Clearly, managers must strike a balance as most libraries do not have staffing levels that allow for individualized service for every patron.

Managers can push organizational culture by examining participation rules and by trusting organizational members with the power to act. Managers need to protect innovation from the slings and arrows of those who may feel threatened. Social media focus on sharing and engaging users around ideas. The ideas that matter most to communities are often ideas that are the most controversial or the most difficult. Organizational culture should give staff a sense of what is appropriate and what is not. It should also empower them to take risks and not to fear difficult situations. Many staff members will avoid conflict and avoid risk and this will give the library a neutered voice on the web.

Management and coordination

Most social media tools grow up organically within libraries. Individuals take ownership and implement them. The tool then becomes defined as the domain of that person. If Eric is the library’s blogger, then the blog will be viewed as serving Eric’s goals rather than the goals of the library. Even worse, other staff members may feel that they are stepping on Eric’s toes or crossing into his turf if they try to post to the blog. A manager can encourage participation by defining the ways that people will work together to move a task forward.

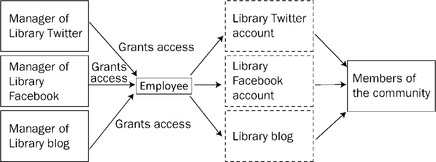

Sometimes staff members may be willing to participate and they may recognize content that could be shared. They may even feel comfortable with the technology, but they are unsure how to get access. Defining some sort of management structure around social media helps ease some of these concerns. As an organization, the library needs to make decisions about how social media will be utilized, which often focuses on defining the individuals who will have responsibility for the tools.

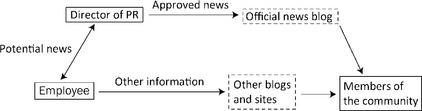

Figure 5.2 defines a general structure around social media that includes a human filter. This example uses blogs, but the structure could work for almost any social media tool. In this example, a staff member consults with the director of public relations prior to posting to the blog. If the item is newsworthy or if it is something that should follow traditional media channels, then the PR staff can take it and promote it on the library’s news blog and via press release. If the item is not as newsworthy, then the staff member can post it directly to the library’s social media sites. For instance, a new reading program may be something that deserves more attention from the organization and therefore will receive a formal media announcement. In contrast, a story about new resources for job seekers may be a nice blog post, but not warrant a full media release.

This structure is fairly useful for organizational members who are new to social media and may not have the confidence to jump in and post. As they use the technology, the structures can become more informal as most staff members will come to recognize whether an informational item is newsworthy and will consult the PR office only if they are unsure. Nevertheless, this sort of approach is especially useful for new social media users because it defines whom to approach with questions about content.

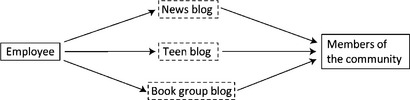

Figure 5.3 outlines an open structure for managing social media. This example uses blogs, but any social media tool could be substituted. This structure is a free-for-all where any employee can access any social media tool. This open approach could be useful for small libraries, where employees spend time together and can discuss how to use social media on a case-by-case basis. This open structure can become the default when social media sites have grown up out of experimentation.

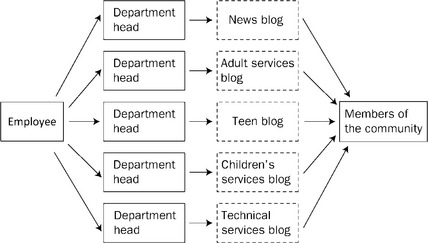

In larger libraries, social media sites are often initiated at the department level, which makes sense considering that goals and audience may vary between departments. Figure 5.4. defines a departmental structure for managing social media. Sometimes employees may move between departments, so employees may be granted access to multiple sites in multiple departments depending on their job responsibilities. The example in Figure 5.3 can be used for any social media tool. This figure indicates that the department head is the person responsible for managing social media tools, but this responsibility could be handled differently in different departments. The formal manager need not be the manager of social media on top of other duties. However, this structure does depend on a single person keeping track of tools and individuals with access.

With the proliferation of social media options, managing multiple sites within a single department can be difficult. Just managing the basics, which might include a blog, Facebook, Twitter and Google +, can be a handful. Throw in Flickr and YouTube, and it can be a nightmare. Figure 5.5 defines an initial structure for managing multiple sites within a department. In this example, each tool is given a manager who would be responsible for keeping track of content and employee access. Libraries may end up identifying individuals who are the local experts on certain tools, and the staff must recognize how to route information to that person for inclusion. This means that a degree of awareness is required by the larger group members. Some software packages help departments manage multiple sites. For instance, the Hootsuite application allows staff to publish to multiple Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Foursquare accounts.

In larger organizations, an additional management structure may be necessary to facilitate communication between departments. This may simply require a social media management committee where social media managers can meet with PR staff to discuss messages and outreach efforts. As described in Chapter 4, libraries can learn from journalism in terms of exploring issues that are important to their communities. Another idea that can be stolen from journalism is that of the front page or editorial meeting. These vary between media outlets, but their essential purpose is to list out the main news items of the day and prioritize them to ensure proper coverage. Managers and leaders in libraries may not want to borrow this literally, but it would not be overly difficult to include discussions of issues covered by social media at department or staff meetings. Coordinating topics ensures that social media sites do not focus overly on one topic while neglecting others. This can also allow staff members to talk about how they will approach specific topics and solicit ideas about other resources that may be tied to issues.

Motivating employees to use

There is a tendency for managers and leaders to think broadly across the organization. They imagine all employees accessing social media tools and using them directly as part of their jobs. The reality is that familiarity with tools and usage of social media tools will be unevenly distributed across the organization. This mirrors usage of social media in general. Power users may make up only 20 percent of users within a social network, but they generate a vast majority of the content (Hampton et al., 2012). Some staff members will generate a great deal of content and others will generate much less. This is fine, and it may be something that managers cannot easily change. Successful social media utilization means engagement in meaningful issues, which cannot be forced upon library staff. In addition, managers should not be overly concerned if one or two individuals dominate a particular social media tool. This is just a reflection of staff personalities.

When it comes to workflows and processes, managers can live with the uneven distribution of work, but, as has been discussed in earlier chapters, having more voices involved with social media is an advantage to the organization. Thus, managers should work to grow participation. Writing policy, shifting culture, addressing participation rules, and outlining structures can increase participation. Training is the final piece to foster change. Training most often focuses on the technical aspects of using social media sites. Creating accounts, logging in, and navigating around new tools clearly take a priority, as new sites cannot be used if staff members do not know the nuts and bolts of using the site. However, training should not neglect the discussions around goals and content. Staff should develop an understanding around how the new social media tool accomplishes organizational goals. This understanding pushes the larger organizational culture and builds connections for staff members between purpose and tools. This is important because this understanding provides the foundation for decision making. It keeps staff focused on accomplishing goals, but it also enables them to recognize opportunities for innovation and growth in the future.

One understanding staff members should have is whether they access tools as individuals or share group logins. Does the library have a corporate voice? This may depend on the particular social media site. Some sites have rules against sharing logins. Most have ways to create pages for the entire organization. On some sites, it will make sense to have a single voice, while others will not. For instance, it may not make sense for every staff member to have a Flickr account for photos as part of their employment. It would make more sense to have a library-wide Flickr account so that all publicly shared photos are together under one account. On the other hand, blog posts tend to make more sense when attributed to a single author, and most blogging software makes it possible to assign individual accounts for each staff member.

Training is time-consuming and expensive. Most libraries are not able to close services in order to train all staff members. This is why training is often focused on key users with the hope that knowledge about the innovation will travel through the organization. In his foundational work on innovation, Diffusion of Innovations, Everett Rogers (1995) describes the three types of knowledge about innovations within an organization. First, he describes “awareness- knowledge,” where individuals know that the innovation exists and start to see the benefits that the innovation may bring. For instance, one department may notice another department’s blog and how easily the blog allows for the publication of information.

Second, Rogers outlines “how-to knowledge,” which is knowledge about the technical and mechanical process needed to make the innovation work. This is important because staff members must evaluate whether the threshold for use is too great to make the innovation worth pursuing. For instance, staff may recognize that a podcast may be a useful innovation for their department. But, after investigating, they may decide that editing MP3 files, managing server space, updating XML files, or dealing with podcast software may not be worth their time and resources.

Finally, Rogers defines “principles knowledge,” which are the foundational concepts tied to system functions. This theoretical knowledge allows staff members to connect an innovation with organizational goals. Principles knowledge is important, because this brings about the insight needed to recognize how a technological innovation can move organizational goals forward. Principles knowledge enables a broader understanding of the technology that can extend to new tools which may enable further innovation.

Often, innovations spread within the organization through the work of a single person. Rogers refers to this individual as an “innovation champion” who has successfully implemented an innovation and helps spread the innovation to other individuals and departments. Innovation champions are not typically managers. They are often risk-takers on the frontlines. When managers and leaders can recognize an innovation champion, they can empower the champion. Often, the innovation champion is the best person to lead training sessions and meet with departments during formal meetings where innovations may be discussed. Champions spread the word and act as symbols for innovation among the staff.

A simple way to encourage staff members to use social media is to create a schedule. This may feel heavy handed or artificial at first, but scheduling one person to be responsible for a site at different times of the day, week or month ensures use. A manager who is trying to establish a Facebook page, Twitter account or a new blog needs to ensure that content will move from staff in the library to the online world. Pages that are not updated regularly look abandoned and forgotten. Scheduling staff member time is a practical way to ensure that content is fresh. This is also a way to build knowledge within a group of staff members. Without a schedule, innovation champions and power users will contribute content but social media novices will be less likely to participate. When novices are assigned a time to post information to a social media tool, they will have to clear up technical questions and find content with value for the community. A lone staff member who wants to grow a new social media presence may find software like Hootsuite to be advantageous. Hootsuite allows for scheduled content, so that a month’s worth of tweets or Facebook posts can be prepared ahead of time. This is a very useful way to ensure content is posted to pages.

Living with mistakes

As managers know, mistakes happen. While mistakes with social media can be quite public, they are unavoidable. Managers must be prepared to let mistakes go and carefully correct the mistakes that cannot be ignored. The goal of policy and infrastructure is to minimize mistakes. Spending time with novice users is important in order to give them guidance and encouragement. Managers and leaders should also attempt to keep an eye on social media tools so that they might catch mistakes before they can be noticed by the community.

If complaints are made by community members, managers must resist overreacting. Grievous violations of policy, serious inaccuracies or hateful comments should be addressed immediately. They should be removed and necessary apologies and needed disciplinary processes should be made. Extremely offensive violations are very rare, as most staff members recognize the line between insulting and appropriate language. Most problems will be minor and exist in gray areas. They should be handled carefully with proper perspective. Minor factual errors should be corrected by the authors that made them. Language that may be terse or overly harsh can be used as a learning opportunity for the future. Complaints from the public that are not about a grievous violation should be dealt with where the complaints originated. For example, a tweet from a user complaining about the length of library hours should be replied to with a tweet. If a user complains on Twitter, a manager should not look up the patron’s name and call his or her house.

Additionally, complaints should be given the degree of attention that they deserve. The best way to turn a small complaint into a major issue is to overreact. Anyone who has spent any time reading blogs know that there will be comments that disagree with any post. Blog authors should resist replying to each comment. Authors should reply to thoughtful comments that further the conversation, but reason must be used. Of course, the best way to turn a major issue into a really major issue is to ignore it. Just because a complaint is made on social media, does not mean that it should not be taken seriously. Some tweets should find their way to the library director and department heads.

Social media can be a great communication tool, and staff training should include a discussion about effective communication. However, managers and leaders also must recognize that the best way to learn is from experience, which will mean some mistakes will be made. Most mistakes will be minor and should be utilized as opportunities for growth.

Finding collaboration, coordination and focus

Chapter 4 discussed many of the possible ways that social media can connect to organizational goals. This chapter has described the ways to build a framework that coordinates staff around these goals. The coordination tools that turn a group of individuals into a functional organization are instrumental in building social media into the fabric of employees’ daily life. Policies, budgets, organizational culture and participation tools are the means used by managers and leaders to drive change. When social media are implemented but coordination tools do not reflect the technology’s advantage, then the new technology will not be fully integrated into the core of the organization.

Most libraries recognize that one additional step to getting exposure to social media is the integration of these tools with the library’s primary web presence. This integration is not just about visibility, but also about recognizing the impact that social media can have. Adding a social layer across a library site can be complicated depending on the size of library and the knowledge of the library’s technology staff. Chapter 6 outlines some approaches to better integration.